Kawasaki has a long and storied history in the sport of motocross.

Kawasaki has a long and storied history in the sport of motocross.

A full decade before Honda took the plunge with their game changing CR250M Elsinore, Kawasaki motocross machines were tearing up the dirt courses of Japan. They were the first of the “Big Four” to wade into the uncharted waters of motocross with a purpose built off-road racing machine and pivotal in bringing the Old World sport of motocross to a new and enthusiastic audience.

Over the years, Kawasaki has often been at the cutting edge of motocross design. Never afraid to push the envelope, the red, and later, green machines have always been quick to embrace new motocross technology. Some of those gambles have paid off (disc brakes) and some have not (bolt-on shock towers), but regardless of the success of the innovation, Kawasaki has continued to try new things and always push forward. This pioneering spirit has helped drive competition and benefited every one of us that throw a leg over a motocross machine.

In putting together this 53-year Kawasaki motocross retrospective, I was struck by how many significant machines have worn that trademark green. Machines big and small, power houses and mini missiles, every one of them important in their own way to the rich heritage of Kawasaki and motocross. In light of that, I thought it might be of interest to highlight a few of the more signifiant machines Kawasaki has brought to market. Not necessarily the best at any one time, just the ones that have had the most impact on the sport as a whole and Kawasaki specifically.

As always, these are just my opinion, so if I left off your personal favorite Kwacker, please feel free to make your case in the comment section below. Most importantly, keep calm, carry on, and always remember to keep the rubber side down.

|

Sit back and check out the evolution ala green. |

|

|

1963 Kawasaki B8M: The machine that started it all. |

The 1963 Kawasaki B8M (sometimes referred to as the “red-tank Kawasaki) stands as the first production motocross machine from Japan. Based off a small street machine known as the B8, the B8M featured a 123cc rotary-valve two-stroke single and four-speed manual clutch transmission. In the transformation from plain-Jane B8 to racy B8M, the Kawasaki engineers stripped the lights, upgraded the forks, raised the expansion chamber, swapped the seat, junked the crossbar-less street bars and bolted on a set of off-road knobbies. Pumping out a claimed 12 horsepower, the B8M was by far the most race-worthy Japanese machine of the day. The bike was so good that it dominated the All-Japanese Motocross Championships in 1963 by sweeping the top six places.

After the immense success of the B8M, Kawasaki’s rivals Suzuki and Yamaha started to take interest in this new form of off-road racing and within a few years, both would have motocross development programs of their own. The B8M and its successors were the first steps in a revolution that would transform Japan from a motocross curiosity to a world power in a few short years.

|

|

1969 Kawasaki F21M Green Streak: The color of money |

In 1968, Kawasaki released their second important off-road racing machine, the F21M. The F21M was designed mainly for scrambles racing, a similar, but less intense off-road discipline than motocross. Unlike the B8M, the F21M was not based off a street bike. Instead, it was designed from the ground up to be a racer. It featured a 238cc rotary-valve two-stroke single and a four-speed transmission putting a claimed 28 horsepower to the ground. These were big numbers in 1968 and the F21M quickly became known for its high-revving horsepower. In 1969, the F21M would gain a new name, “Green Streak” and with it, a change in color from red to green. This made the ’69 F21M Green Streak the first Kawasaki to wear the now familiar lime green and cemented its place on our list.

|

|

1970 Kawasaki GM31 Centurion: Little green holeshot machine |

In the mid-sixties, motocross was still a bit of a curiosity in America. It was big in Europe and quickly catching on in Japan, but not quite on most people’s radar here in the states. In 1967, all that changed with the work of an enterprising man by the name of Edison Dye. Dye had the bright idea that he could sell more Husqvarna’s if he brought over some of Europe’s stars to show what the bikes were capable of. Dye’s exhibition series proved to be a huge success (so much so that the AMA stole it from him) and America’s love affair with motocross was born.

While motocross in America was on a huge upward swing in the late sixties, Kawasaki USA was barely known. American operations had opened in 1966 and by 1968, they had a nationwide distribution network in the works. In 1969, the arrival of the high-performance Mach III street machine put them on the map of road bike enthusiasts, but off-road guys continued to ignore the little two-strokes with the funny name.

All that changed in 1970, with the introduction of a little green rocket by the name of G31M Centurion. Often referred to as the “baby Green Streak”, the G31M was a small-bore powerhouse, pumping out an unheard of 18.5 horsepower from its 100cc rotary-valve single. At the time, this was nearly double what most 100cc machines were putting out.

Just as with the F21M, the G31M was not designed specifically as a motocross racer, but it was easily modified for the demands of the new discipline. After word got out on the little green meanies, Centurions were ripping holeshots at tracks all across the nation. While the motor was a powerhouse, it was extremely high strung and required a locked right wrist to get the most out of its high-revving nature. The chassis and suspension also left a lot to be desired, but most people at the time did not care. For them, it was all about the eerie shriek emanating from that tiny exhaust stinger. The G31M Centurion stands as the bike that introduced America to the joys of Kawasaki horsepower and put the brand on the US racing radar for the first time.

|

|

1974 Kawasaki KX250: The progenitor of a proud pedigree |

In 1974, Kawasaki would make its most serious off-road commitment to date with the release of an all-new line of motorcycles designed solely for motocross racing – the KX. The KX’s were significant machines because they represented the first bikes from Kawasaki designed from the ground up to be serious motocross racers. Prior racers had been modified street bikes (B8M, J1M, B1M), scramblers (F21M), TT racers (G31M) or stripped enduro bikes (F81M, F11M, F12M). The new KX on the other hand, was crafted from the beginning to do but one thing; win motocross races.

The new KX250 featured a chrome-moly steel chassis (stronger than the mild steel found on most Japanese brands of the day, but not as sturdy as the ultra-tough chrome-moly steel found on Husqvarna’s) and a piston-port two-stroke single feeding power through a wet clutch and five-speed gearbox. In the suspension department, the KX featured 5.8 inches of movement up front and a standard for the time, 3.5 inches of travel in the rear. Unfortunately, neither end was very good and the KX had a hard time keeping up with the established Honda Elsinore and amazing new Yamaha YZ.

Even though the KX250 failed to set the world on fire in ’74, it did signal a shift toward more serious racing machines from Kawasaki. It would take them several more years to finally catch the likes of Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki, but eventually the green machines would claim the top spot in the motocross rankings. Today, the KX line is one of the most successful in all of motocross, and that lineage stars here.

|

|

1978 Kawasaki KX250 A-4: A works bike for the chosen few |

Even after the introduction of the KX250 in 1974, the green machines had failed to gain traction in the marketplace. First the Honda, then the Yamaha, and later the Suzuki took turns dominating the top of the 250 motocross charts. In 1977, Kawasaki did not even produce a motocross machine and most green dealers were more interested in selling Z-1000’s than cases of two-stroke oil.

In 1978, that attitude changed with the introduction of Kawasaki’s first official “works-replica”, the ultra-trick KX250 A-4. The A-4 tipped the scales at a featherweight 206 pounds and pumped out a rip-snorting 40 horsepower (claimed) from its 249cc’s. Long-travel suspension graced the KX for the first time and a Boyesen reed-valve (a first for any manufacturer) gave the bike instant throttle response. Power and handling were pro-focused, as one would expect from a Weinert replica and the KX was aimed squarely at expert racers only.

Available in extremely limited numbers (an estimated 1500 total), the KX250 A-4 was more about Kawasaki’s renewed commitment to racing than selling big numbers. At the time, it was important to demonstrate that the green team was serious about motocross and the A-4 showed that in spades. It put Kawasaki back in the game and made it clear that they could indeed compete with the other Big Four manufacturers.

|

|

1979 Kawasaki KX80: The start of something big |

In 1979, Kawasaki entered the mini motocross game for the first time with the introduction of the all-new KX80. Slightly larger than the Suzuki and Yamaha 80’s of the time, the new KX featured a torquey two-stroke motor, five-speed transmission and rugged motocross-ready suspension. The mini-cycle class was big business in the late seventies and the arrival of the KX80 gave Kawasaki an important foothold in the exploding entry-level segment. While not the best performer in the class, the mini KX proved a great success for Kawasaki. It introduced thousands of young racers to the joys of riding green and paved the way for what would eventually become the most successful grass roots amateur motocross program in the sport’s history, Team Green.

|

|

The 1980 Kawasaki KX125, KX250 and KX420: Have linkage will travel |

In the late seventies, motocross suspension design was moving at a break-neck pace and all the manufacturers were caught in a battle of technological one-upmanship. In a mere five years, travel had grown from a kidney busting 3 inches, to an eye-opening full foot of articulation. By 1979, most of the manufacturers had settled on 11 to 12 inches as the optimum amount of travel and the focus began to shift from quantity, to quality.

|

|

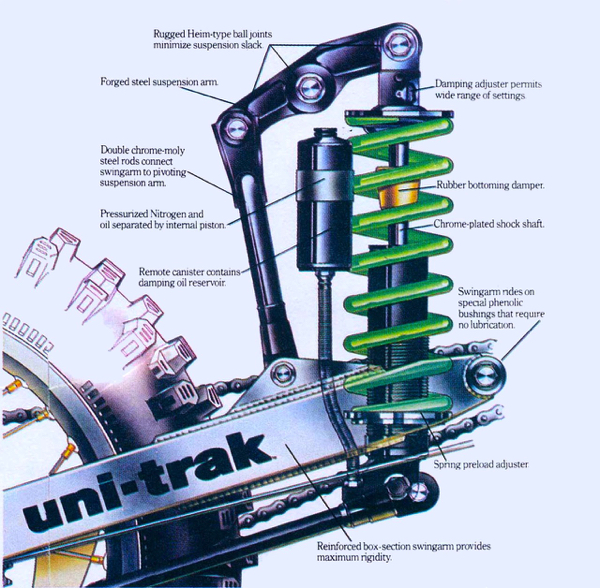

The first production single shock design to utilize a linkage system, the 1980 Kawasaki Uni-Trak paved the way for the Supercross-bred suspension we use today. |

In 1980, Kawasaki took the first major step in this direction by incorporating a linkage into its rear suspension for the first time. Originally named the “Bell Crank” in Japan, the design that would become the Uni-Trak consisted of a large vertically mounted single shock, connected in a see-saw layout to a bell crank (hence the name) by a set of steel pull rods and bolted to a large alloy swingarm. The Uni-Trak design was inspired by the need to offer better small bump performance, while still allowing good bottoming resistance on big hits. The addition of the linkage allowed the engineers to vary the forces placed on the shock at different speeds and better fine-tune performance.

Initially, the Uni-Trak did not perform appreciably better than the conventional dual-shock arrangements of the time, but it did prove there was potential in the new design. Later iterations would improve performance and become lighter by replacing the heavy steel components with lightweight alloy alternatives. In 1980, the Uni-Trak did not immediately make every other suspension systems obsolete, but it did blaze a trail that all other off-road manufacturers would follow within a few short years.

|

|

1982 Kawasaki KX125 and KX250: Better living through hydraulics |

In 1982, Kawasaki became the first major manufacturer to equip their stock machines with disc brakes (with all due respect to Rokon, who had equipped their wacky machines with disc brakes in the mid-seventies). This was a major innovation at the time, as the power and suspension capabilities of modern motocross machines were quickly outstripping the braking power afforded by conventional drum brakes.

|

|

In 1980, Kawasaki debuted their first disc-equipped Factory racers in the All-Japanese Nationals. Early versions of this braking system (like the one seen here on Goat Brecker’s KX250SR) actually mounted the caliper forward of the lower fork tubes in an effort to keep the caliper out of harm’s way and find the best placement for power and feel. |

For eighty years, the drum had proven an effective and reliable way of stopping a vehicle, but as more and more machines moved to hydraulic discs in the seventies, it started to look like its days were numbered. The switch from 120mm hubs to 200mm units and advances like dual-leading shoe linkages had kept the drum in the hunt, but by 1980, the writing was on the wall.

In 1979, Kawasaki first started development on a disc brake for motocross use and by 1980; they had a prototype ready to be raced in the All-Japanese Motocross Nationals. Early concerns about the effectiveness of the system in water and mud proved unfounded, but there were problems with cracked calipers, warped rotors and misrouted cables. While powerful, the early disc systems proved grabby and prone to squealing and it took engineers and test riders several iterations to find the best material combinations for off-road use.

By 1981, the Kawasaki engineers had the basics figured out and the new braking system made its debut on the 1982 Kawasaki KX125 and KX250 (the KX420 took the year off after a disastrous ’81 outing) to much fanfare. For riders raised on the feel and power of drum binders, the new discs were both a blessing and a curse. Where four fingers were required to bring a ‘81 KX420 down from speed, the same task could be accomplished with just one on the new ‘82 KX250. This newfound jump in braking power actually put some riders off and many preferred the comfort of their familiar drums. History, however, would prove that the days of the drum were quickly fading away and Kawasaki’s bold move to embrace this new technology was the right one.

|

|

1983 Kawasaki KX60: The bike that launched a thousand careers |

The 1983 Kawasaki KX60 was far from the first pint-sized motocrosser to come from Japan, but right from the start, it was the best. In 1983, all the Big Four offered 60cc mini racers for aspiring Bob Hannah’s to choose from. The all-new KX60 and CR60R vied for showroom victory with the slightly more long-in-the-tooth RM60 and YZ60. All four offered different levels of performance, with the YZ and RM appealing more to smaller and less skilled riders, while the CR and KX offered junior more room to stretch his abilities.

The KX in particular was the choice of aspiring throttle jockeys, offering the most power and suspension in the class. It was bigger, faster and more capable than anything else available at the time and quickly caught on as the hot ticket for collecting trophies at Chicken Licks Raceway. Within a few short years, the KX had laid waste to the 60cc competition and stood as the last 60cc mini-cycle available for sale.

A 1985 upgrade to liquid cooling would be the last major refinement the evergreen KX60 would receive (aside from a yearly dose of Bold New Graphics) until its eventual demise in 2003. For 20 years, the KX dominated 60cc class racing in America, taking home countless amateur National titles along the way. Kevin Windham, Ricky Carmichael, Robbie Reynard, James Stewart, Mike Alessi and Ryan Villopoto all took turns winning aboard the venerable Kawasaki 60. It was a bike so good, it scared away the competition and so influential, it played a part in nearly every major professional career for nearly two decades. That is a resume any machine would be proud to own.

|

|

1985 Kawasaki KX125 and KX250: KIPS-equipped Kermit Krossers |

In the heyday of the two-stroke motor, it was its lightweight design, simple construction and impressive peak power output that made it such an attractive racing alternative. It was lighter, easier to work on and more powerful per cubic centimeter than the booming thumpers of the day. Where it fell short was in the breadth of its power, where the smooth and tractable four-stroke held a distinct advantage.

In the seventies, the addition of a reed-valve to the intake helped improve response and the switch to liquid cooling in the early eighties, combined with advances in carburetor technology, helped the manufacturers push horsepower figures ever skyward. While more potent than ever, these racing two-strokes continued to offer fairly narrow spreads of power. They were explosive and fast, but typically unable to carry that power over a broad range of RPM.

In 1982, Yamaha took the first step toward addressing this issue with the introduction of their Yamaha Power Valve System (YPVS). The YPVS used a rotating drum placed at the top of the exhaust port to vary port timing based on engine RPM. In theory, this allowed the engineers to offer two porting configurations in one motor, to best optimize the flow characteristics for a broader powerband.

In 1984, Honda introduced its version of a power widening gizmo in the form of the Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber, or ATAC. The ATAC took a different approach than Yamaha, in that it did not alter the port timing. Instead, the ATAC tried to widen the powerband by adding a small sub-chamber to the exhaust port to increase head volume at low rpm. At low rpm, a flapper valve opened, allowing exhaust gas to fill the chamber before exiting the exhaust. At high rpm, the valve closed, allowing unimpeded flow to the expansion chamber. This allowed the CR motor to behave as if it had two differently tuned pipes, one configured for low- end and one tuned for top-end power.

|

|

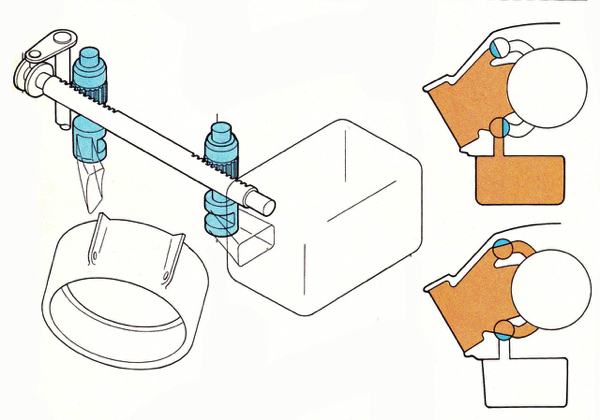

In 1985, Kawasaki introduced its version of a two-stroke “Power Valve” for the first time. Dubbed KIPS (for Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System), the new design integrated the resonance chamber of Honda’s ATAC and the variable port control of Yamaha’s YPVS. |

While both systems were a step in the right direction, it was Kawasaki that finally cracked the code of how to best implement these new technologies. Their solution was the handiwork of chief motocross engine designer Eizaburo Uchinishi, who incorporated the theories behind both the ATAC and YPVS into one mechanism. Dubbed the Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System (KIPS), this new design featured both an exhaust sub-chamber and a variable exhaust port to boost engine torque.

The new design would make its production debut in 1985 on the new Kawasaki KX125 and KX250 (the KX500 would get the Power Valve treatment a year later in 1986). Both the 125 and 250 were potent performers, with the small KX in particular holding a significant power advantage over its classmates. As with any new technology, it would take Kawasaki a few years to refine the KIPS’ potential and later versions would incorporate a second valve to alter exhaust-port timing and a 2-stage operation for the sub-ports.

Perhaps the best endorsement for Uchinishi’s design came from the competition. In 1992, Honda introduced a new KIPS-like Composite Racing Valve (CRV) on their new CR250R and in 1995, Yamaha integrated a resonance chamber into their proven YPVS design for the first time. Today, the KX125, KX250 and KX500 are but a memory, but the KIPS lives on in Kawasaki’s mini-class rockets, the KX85 and KX100.

|

|

1987 Kawasaki KX80 Big Wheel: Junior gets an upgrade |

With the demise of the 100 class in America in the early eighties, a void was left in the market for kids too big for an 80, but not quite ready for a 125. In 1987, Kawasaki addressed this issue with an all-new model (at least in the US), the Kawasaki KX80 “Big Wheel”. Popular across the pond for Schoolboy class racing, big-wheeled 80’s made a perfect transition machine for kids not quiet big enough for a full-size bike.

The new Big Wheel bumped up the diameter of the wheels two inches front and rear (19” front and 16” in the rear) and extended the wheelbase with a longer swingarm. The motor and basic chassis remained unchanged, but the overall bike offered a little more room to grow. For kids large enough to make use of the bigger bike, the Big Wheel offered superior handling and greater stability over its small-wheeled sibling. Eventually, the Big Wheel model diverged from the regular 80 with upgraded suspension components (the Big Wheel got the switch to USD forks sooner) and in 1995, a bump to 100cc’s. Perhaps most significant, the introduction of the KX80 Big Wheel gave rise to the Super Mini class in America, which continues to thrive to this day.

|

|

1988 Kawasaki KX500: The Jolly Green Giant |

Kawasaki’s history in the Open class is a bit of a rags-to-riches story. Early Open class Kwackers were anything but excellent and basically an afterthought in the marketplace. From 1977 to 1979 Kawasaki did not even bother to make an Open bike, and when they reentered the market in 1980, it was a bitter disappointment. The 1980 KX420 was an overweight, ill-handling and poor-running mess of a bike that was so lambasted by the media that Kawasaki refused to give them to magazines to test the following year. It rattled, it vibrated and it swat off its pilots like a mechanical bull with a mischievous streak.

In 1982, Kawasaki took the season off to regroup and came out with an all-new machine for ’83 – the first KX500. Unfortunately, the big green meanie was once again too heavy, too tall and nearly impossible to ride. The motor blubbered and pinged incessantly and liked to grenade when pushed. The suspension, chassis and overall handling were more or less terrifying and the bike was a handful for even the most skilled of pilots to manage.

After another disastrous year in ‘84, Kawasaki came out swinging in 1985 with an all-new KX500. The new green five-honey received the water-cooling treatment for the first time and with it, a slight decrease in its notorious pinging. Reliability continued to be a KX500 bugaboo, the Kawasaki once again brought up the caboose in the 500 standings.

The 1986 season brought with it another major revamp for the KX500, but this time it was with much better results. A new KIPS equipped motor finally cured its lingering powerband issues and chassis refinements at last delivered a 500 Kawasaki that handled better than a runaway school bus. The addition of a rear disc brake aided stopping and a revised Uni-Trak rear gobbled up the bumps. Overall, it was the best Kawasaki Open bike in history and a front fork away from wresting away the title of best 500 in the land.

The ’87 KX500 would see further refinements with an ultra-slim layout and new bottom-link Uni-Trak. The new KX was literally half the width of the porky CR and a solid handler. The KIPS motor continued to impress with its smooth and abundant power, but finicky carburetion and an incredibly harsh set of TCV front forks held it back in the final standings.

This brings us to 1988, the real watershed year for the KX500. An all-new green frame and redesigned bodywork refreshed the look of the half-liter ground-pounder and the additions of Kayaba’s excellent cartridge fork and Mikuni’s new PKW39 crescent-slide carb finally addressed the last of its glaring issues. Gone was the slim layout of the ’87 KX, but the rest of the bike was majorly improved.

What truly made the ’88 KX500 such a great machine was its incredible motor. In an era dominated by 60 horsepower terror machines, the KX was a fire-breathing pussycat. The KIPS allowed the KX to pump out an amazing amount of power, while also being smooth and controllable. It offered comparable thrust to the blistering-fast Honda, but did it in a much more civilized fashion. If you needed to torque around a tricky off-camber, it was up to the task. If you needed to pin your eyeballs back to clear the Himalayas, all that thrust was a mere flick of the wrist away.

Handling of the new chassis was much improved and the KX offered the best combination of cornering and stability in the 500 class. The new KYB cartridge forks were 1001% better than the grim ’87 offerings and the overall bike was by far the best overall package of 1988. Its only real shortcomings were its pudgy layout, brittle plastic and suspect component quality (best to buy footpeg springs in six packs).

In 1989, the KX would get a bump up in fork size and in 1990, the mighty 500 would switch to upside-down forks and a 19” wheel (a move none too popular with the Baja set). Other than suspension refinements and a revolving door of BNG, the first and last great KX500 would soldier on mostly unchanged for nearly two decades of off-road domination. It captured four of the last five 500 National Motocross Championships run and roosted to countless off-road victories with legends like Ty Davis, Larry Roeseler and the late great Danny Hamel at the controls. Today, the KX500 is a motocross icon, because in 1988, Kawasaki finally got it right.

|

|

1990 Kawasaki KX125 and KX250: Buck Roger’s personal berm busters |

In 1989, the full size KX’s were just about the dowdiest looking machines in motocross. They were big, bulky and old fashioned looking. The rear fender looked more like a snow shovel than a piece of racing equipment and the poor little 125 was still saddled with a single large radiator on one side that made it look like a KX from 1982. Compared to the sexy Honda, racy Suzuki and works-like Yamaha, the poor KX’s looked like mini vans lost at a Mustang convention.

All that changed in 1990 with introduction of the all-new Kawasaki KX125 and KX250. The new machines were a complete 180 from their conservative looking predecessors with futuristic looking bodywork, road race inspired steel perimeter frames, bolt-on alloy shock towers and outlandish (for the time) graphics. They looked like bikes from the future and immediately caught the imagination of the motocross buying public.

Actual performance was quite good and both bikes acquitted themselves well on the track. The 125 was a huge improvement over the anemic ’89 model and the 250 continued to offer one of the fastest motors on the track. The new chassis was heavy and bulky, but it offered previously unknown levels of rigidity. Suspension was also very good and both bikes were near the top of the class.

While not perfect, the 1990 KX’s were groundbreaking machines that had a significant impact on the sport. They were the first machines to bring us ultra-wide platform footpegs (your ankles thank you) and the forerunners of the ultra-ridged alloy perimeter frames common on all Japanese machines today. They blazed trails in styling and led to an explosion of crazy colors and outlandish graphics in the early to mid-nineties (depending on your age, you may or may not be thankful for this). Perhaps most importantly, they once again demonstrated Kawasaki’s commitment to push the envelopes of design and challenge the motocross status quo.

|

|

2000 Kawasaki KX65: A micro mini for the new millennium |

By the mid-nineties, the venerable KX60 had enjoyed an unchallenged decade at the top of the 60cc charts; but the times, they were a changin’. The introduction of upstarts like Cobra and the return of a revitalized KTM to the mini ranks started to put a little pressure on the grande dame of pint-sized racers. The littlest KX had not enjoyed an update since Reagan was in office and its dog-bone Uni-Trak and drum brakes were starting to look as out of style as mullets and Members Only jackets.

With Y2K approaching and the shut down of all society eminent, Kawasaki decided the time was right to finally introduce an all-new mini racer. The 2000 Kawasaki KX65 was completely new from the ground up and every bit a modern machine. A powerful new liquid-cooled 64.7cc motor provided thrust through a manual clutch and six-speed transmission. Beefy 33mm forks offered a full 8.3 inches of travel in the front (.4 inches more than the KX60) and an all-new bottom-link Uni-Track punched out a full 8.9 inches (12 inches more than the KX60) in the rear. Disc brakes front and rear hauled the KX down from speed and offered a quantum leap forward in braking performance over the old KX60.

Initially, Kawasaki kept the KX60 in the line up to appeal to smaller riders, but in 2003, the old girl was put out to pasture for good, leaving the KX65 as the sole Japanese offering in the 65cc class (excluding of course, the yellow version rebadged as a Suzuki RM65, but more on that later). In 2003, the KX65 would also get a slight bump in suspension travel, but has otherwise remained unchanged (aside of course from the yearly dose of BNG). Today, the KX65 remains the only 65cc offering from the Big Four and stands as a testament to Kawasaki’s long-standing commitment to the roots of our sport.

|

|

2004 Kawasaki KX250F: A flawed first step toward a four-stroke future |

The 2001 season was an eventful one in the world of motocross. In March of that year, the MX press was shocked to learn that Yamaha was bringing to market a 125-class legal version of their amazing YZ426F thumper – the YZ250F. The new 250F was going to compete head-to-head with 125 two-strokes and rev to an ear splitting 11,000-rpm. This was absolutely unheard of at the time, as no sub-350cc four-stroke had ever proven even remotely competitive with the two-strokes on equal footing.

With this news, it became very apparent that the other Big Four Japanese manufacturers needed to get their thinking caps on in a hurry. None of them even had an Open class four-stroke ready to compete with the YZ426F and now Yamaha was going after their 125 business as well. No one knew for sure if the new YZ250F would even be competitive, but if the YZ400F were any indication, they would be foolish to stand pat and get left behind.

In August of 2001, Suzuki and Kawasaki took a bold step toward bolstering their market position by purposing an alliance between the two brands. Both manufacturers would remain autonomous, but each brand would share products that did not overlap (hence the yellow KX65) and pool their resources to design and manufacture a 250F to compete with the new Yamaha. Both teams would work together, with Kawasaki focusing on the chassis and Suzuki developing the motor. Final assembly would be handled by Kawasaki and both brands would sell the machine with minor changes to differentiate the two.

In August of 2003, the much-anticipated Kawasaki KX250F/RM-Z250 made their debut to much fanfare. The chassis and bodywork were 100% Kawasaki and featured their trademark steel perimeter frame and unmistakable KX looks. The motor itself was a fairly conventional design, with much of the technology being pilfered from Suzuki and Kawasaki’s sport-bike catalog. Dual-overhead cams actuated four valves and were fed by a 37mm Keihin FCR carburetor. Like the Yamaha, the KX250F used a road-race style “slipper” piston to provide low reciprocating mass and a high-rpm ceiling.

|

|

Other than color and a slightly different radiator shroud, the Kawazuki twins were identical. |

On the track, the new KX250F (and by default, its identical twin, the RM-Z250) provided a very different character than the established YZ250F. Where the YZF preferred to be ridden like a 125, the KX/RM required a more 450 approach. Power was torquey and twins worked best when short-shifted instead of wrung out. While this was different from what many people were expecting, it was not really a disadvantage. The power was competitive and the bike handled decently, but it was not going to be mistaken for a RM in the corners. Overall, the bikes were flawed, but fun to ride.

As with nearly any completely new design, there were bound to be problems and these issues led to tension between the two companies. The bikes were well received initially, but when the new motor proved unreliable, it reflected badly on both parties. Eventually, tensions rose to the point that neither was happy and in May of 2006, Kawasaki and Suzuki decided to end their alliance.

While the original KX250F certainly had its issues, it was still a very important machine for Kawasaki. It was vital in 2004 for Kawasaki to get in the game and show that they were capable of competing with Honda and Yamaha in this exploding market. The four-stroke was looking very much like the wave of the future and it was starting to look like the green team was falling behind. The alliance with Suzuki bought Kawasaki some much needed breathing room and a little time to get it right, something they would do with the second generation of their 250F machine.

|

|

2006 Kawasaki KX450F: The return of the Open class Kwacker TransworldMX Photo |

In 2006, Kawasaki became the last of the Big Four Japanese manufacturers to unveil an Open class four-stroke. Amazingly, this was a full eight years after the original Yamaha YZ400F shocked the world in 1998. Yamaha had taken the rest of the manufacturers by surprise with their high revving, road race inspired racing thumper and it took all of them several years to catch up. By 2002, both KTM and Honda had big-bore four-strokes in the hunt and plans were set for Kawasaki to unveil their new valve and cam racer in the fall of 2004.

Unlike the 250F, the new 450F was a 100% Kawasaki project and not affiliated in any way with Suzuki’s development program. The new bike was set to use a unique D-style alloy frame that was completely unlike anything else on the market and be powered by a traditional short-stroke DOHC four-stroke single. In, 2004 things looked good for a 2005 model year release, but unfortunately, the prototypes being raced in Japan suffered some very high profile frame failures that led the engineers to scrap the D-style frame design completely.

|

|

Originally, Kawasaki’s first KX450F was supposed to have a very different look than the one that made it to market in 2006. Prototypes raced in Japan used a unique D-shaped frame more reminiscent of a Honda XR650R than a KX250. When prototype frames began braking in Japan, Kawasaki scrapped the original design and went with an alloy perimeter configuration similar to what Honda was using on its CR and CRF line. |

Forced to go back to the drawing board, Kawasaki decided to go with a more traditional alloy perimeter frame similar to the ones Honda had been utilizing since the late nineties. This was a proven design and provided a sturdy and flex-free platform that could handle the immense power and torque of the new 449cc power plant. This setback in development pushed back the arrival of the KX450F over a year and the new bike would not make its debut until September of 2005.

Once the new KX450F finally hit the market, it was an instant success with a buying public intoxicated by the allure of the new valve-and-cam craze. It was not the best 450F of 2006, but it was competitive and a very solid first effort. By far the biggest complaint was with the four-speed transmission, which severely limited its versatility. In 2007, the KX450F would get its longed-for fifth gear and claim Kawasaki’s first Supercross title in six years with James Stewart aboard.

Kawasaki’s entry into the four-stroke game may have been late and a bit bumpy at the start, but they quickly righted the ship with some of the best race bikes in the sport. In the years since their introduction, the KX250F and KX450F have claimed no less than 14 major AMA Motocross and Supercross titles. That is a pedigree no other four-stroke manufacturer can claim.

|

|

2014 Kawasaki KX85 and KX100: Mean green pumpkin hunters |

When Honda went to a 150 four-stroke in 2007, most pit pundits thought the writing was on the wall for the venerable two-stroke mini. Rumors of a purposed YZ150F had been circulating since the arrival of the original Yamaha 250F and it seemed inevitable that the days of 85cc two-strokes were numbered. A funny thing happened on the way to the bone yard however; the two-stroke started to make a comeback.

KTM, long the champion of the oil-burner, continued to pour development dollars into its racing smokers and perhaps most important, the AMA did not make the same mistake with the 150 that they did with the 250F. Unlike the 450F and 250F, which were allowed to run legally in the 250 and 125 class, the new CRF150R would not be allowed to compete in the 85cc division. It was legal only in the Super Mini class, where it would face larger machines.

Another factor staving off the demise of the 85 was fact that Honda’s 150 did not prove to be the mini killer the 250F had been. As it turned out, the threshold for a omnipotent four-stroke was somewhere north of 150cc’s and the CRF, while easier to ride, was not significantly better than the best two-stroke minis. Its wide powerband was an advantage, but it was heavier and actually put out less power than a strong running 85 and 100 smoker.

Even though four-stroke Armageddon was averted (for now at least), Kawasaki, Yamaha and Suzuki seemed content to sit back and keep cranking out decades old minis. The YZ and KX could trace their roots back to the early nineties and the RM’s stretched all the way back to the late eighties. Along the way, they had all enjoyed suspension upgrades and some minor bodywork improvements, but the basic machines remained largely unchanged from the days of 90210 and Pearl Jam.

For 2014, Kawasaki finally decided to retire their mini workhorses and introduce an all-new KX85 and KX100. Significantly, the new bikes remained two-strokes, which were lighter, easier to work on, and less costly to repair than a comparable thumper. The new machines featured radically redesigned bodywork (designed to mimic the KX250F), upgraded suspension and a major boost in power. The frames remained largely unchanged, but the overall machines enjoyed an all new character.

Perhaps most significant were the power upgrades that finally brought the KX within reach of the blazing fast Austrian competition. A new cylinder, head, single-ring piston and expansion chamber boosted power a full four horsepower over 2013 and offered a broad and easy to ride power curve. The KTM and nearly identical Husky offered more peak power, but they were harder to ride and more expert oriented. At $4349, the new KX cost $300 more than the rebadged 1998 machine it replaced, but it still undercut the European competition by a full $1000.

The 2014 Kawasaki KX85 and KX100 are significant because they represent both Kawasaki’s commitment to continued two-stroke development and mini-class racing. With Honda stubbornly refusing to rethink their all four-stroke strategy and Suzuki and Yamaha content to rehash old designs, it is important that someone besides KTM is willing to invest in new product in a traditionally neglected division. Nothing helps the breed more than competition and we can all thank Kawasaki for helping to keep the two-stroke oil burning. #Braappp

|

|

2016 Kawasaki KX450F: Slimmed down, toned up and ready to race |

In all fairness, it is much too early to officially add the 2016 KX450F to this list, but the initial specs are certainly appealing. It is no secret that one of the major issues with four-strokes has always been weight. They are big bikes with lots of moving parts and have tended to be correspondingly heavier than the two-strokes they replaced. The addition of fuel injection and its associated hardware have only made that worse.

Honda was first to bring back a little sanity to the ballooning waistlines in 2009 and KTM has done amazing things with their incredibly svelte Factory Edition machines. Now, Kawasaki has finally entered the game and put their immensely successful KX450F on a weight loss program. The new 2016 boasts a whopping 6.6 pound drop in unwanted suet and is slimmer and more compact to boot. A new 270mm front disc looks to give Brembo a run for their money and numerous engine upgrades promise lots of holeshots in 2016. With its adjustable bar mounts and selectable peg positions, the new KX450F is not just lighter; it is also the most customizable stock 450 on the market today. The jury is still out on the SFF-Air TAC front forks, but there can be no doubt this new KX will be at or near the top of the charts once again.

With the new 2016 KX450F pointing the way forward, all of us can rest assured that Kawasaki is ready and willing to keep investing in the sport we love. They were the first to the party in 1963, and remain one of the most committed to motocross innovation in the new millennium. Let the good times roll.