This week’s selection from Greg Primm’s Classic Steel collection is one of my personal favorites, the 1986 Honda CR250R Factory Racer.

The 1986 CR250R was the first of Honda’s Factory production race bikes. With the stock CR being such a strong starting point, Honda had a huge advantage over its racing competitors in 1986. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The 1986 CR250R was the first of Honda’s Factory production race bikes. With the stock CR being such a strong starting point, Honda had a huge advantage over its racing competitors in 1986. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The 1986 season was a significant one for American motocross. This was the first year for the AMA’s new Production Rule. Prior to 1986, there was virtually no limit to what the factories could do to their race bikes. As long as it was above the weight limit and below the displacement limit, pretty much anything went. In the seventies, virtually all the Japanese factories had gotten in on this incredible spending spree, building one-of-a-kind race bikes for their riders. In the early eighties, that started to change as some of the manufacturers decided to start dialing back on their astronomical race team budgets. At the end of 1983, Yamaha decided to do away with their “works” bikes entirely and race stock bikes for the ’84 season. This was at a time when Honda was reportedly spending over six figures on each of their one-off HRC race bikes. This incredible discrepancy between the haves and have-not’s led to the proposal of the Production Rule for AMA motocross.

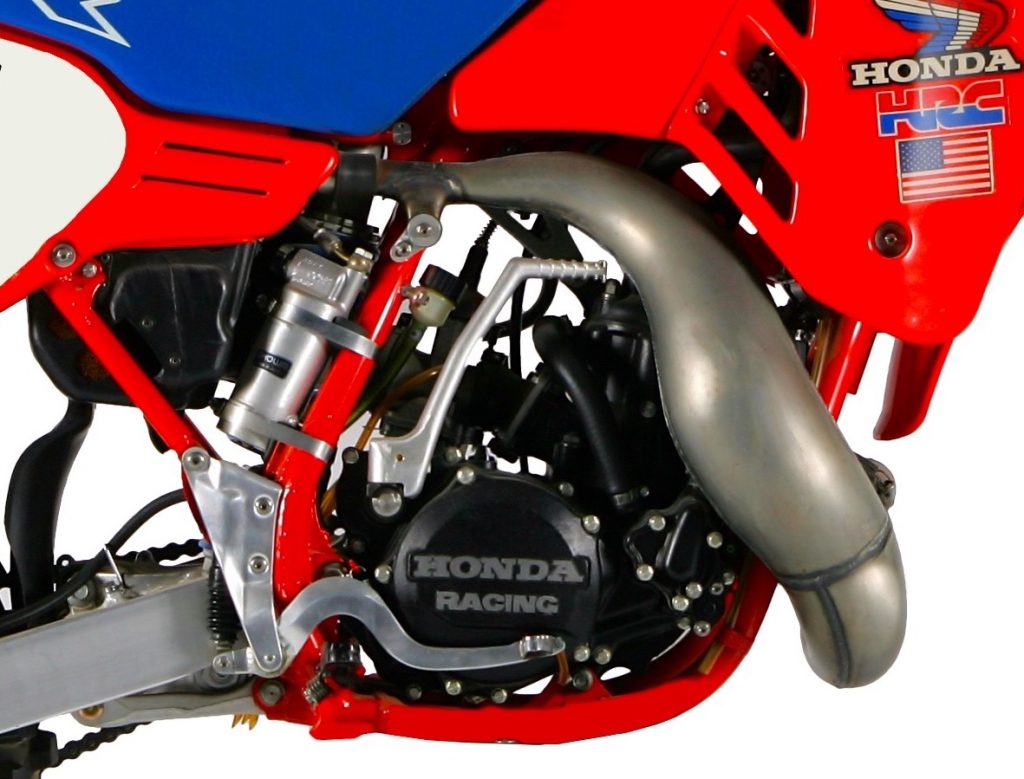

A wolf in sheep’s clothing: While externally very stock looking, Ricky’s HRC motor actually shared very little internally with the standard CR250R. Works porting, reshaped HPP valves, an HRC crank and an HRC piston helped pump up the power to championship-winning levels. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

A wolf in sheep’s clothing: While externally very stock looking, Ricky’s HRC motor actually shared very little internally with the standard CR250R. Works porting, reshaped HPP valves, an HRC crank and an HRC piston helped pump up the power to championship-winning levels. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The AMA production rule meant that all the teams would have to race production-based machines in the Supercross series and AMA Nationals for the ’86 season. All the Factory team’s race bikes would have to start out as showroom-stock machines. Some minor modifications would be allowed to things like porting and suspension, but the basic frame and engine cases would have to remain close to stock. Since this would put an end to the exotic HRC Honda works bikes, it was assumed by many that this would even the playing field for the other teams. As it turned out, Honda actually became even more dominant under the new rules.

Honda’s Factory riders could choose from an extensive list of works parts to customize their bikes to their liking. The small aluminum boot guard was fabricated because Johnson kept getting his boot stuck in that area. Footpegs, control levers, brake pedals, seats, and sub-frames could all be modified to improve the comfort of the rider. In Supercross, Johnson preferred to run a Pro Circuit pipe due to its strong low-end performance. Outdoors, he switched to an HRC pipe (pictured) because of its longer-pull and strong midrange. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Going into the ’86 season, Honda made the wise decision to sign 21-year-old Rick Johnson to the Factory team. Johnson had been with Team Yamaha since turning pro at 16, enjoying several productive seasons and even capturing the 1984 250 National Motocross title for the yellow brand. Johnson had always been fast, but he was also inconsistent in the early part of his career.

On and off the track, Ricky Johnson was an all-new man in 1986. Photo Credit: Pete Fox

The move to Honda would signal the next step for the kid from El Cajon. On the red machines, Rick would transform himself from just one of the fast guys, into the fast guy. Riding a production-based CR250R, Johnson would capture the 1986 Supercross and 250 National Motocross titles. The only title that would elude his grasp would be the 500 National Motocross crown. That one would go to his Honda teammate David Bailey. With Johnson, Bailey and Johnny O’Mara on the red machines, Honda would dominate the ’86 season, capturing all three major titles and countless podium finishes.

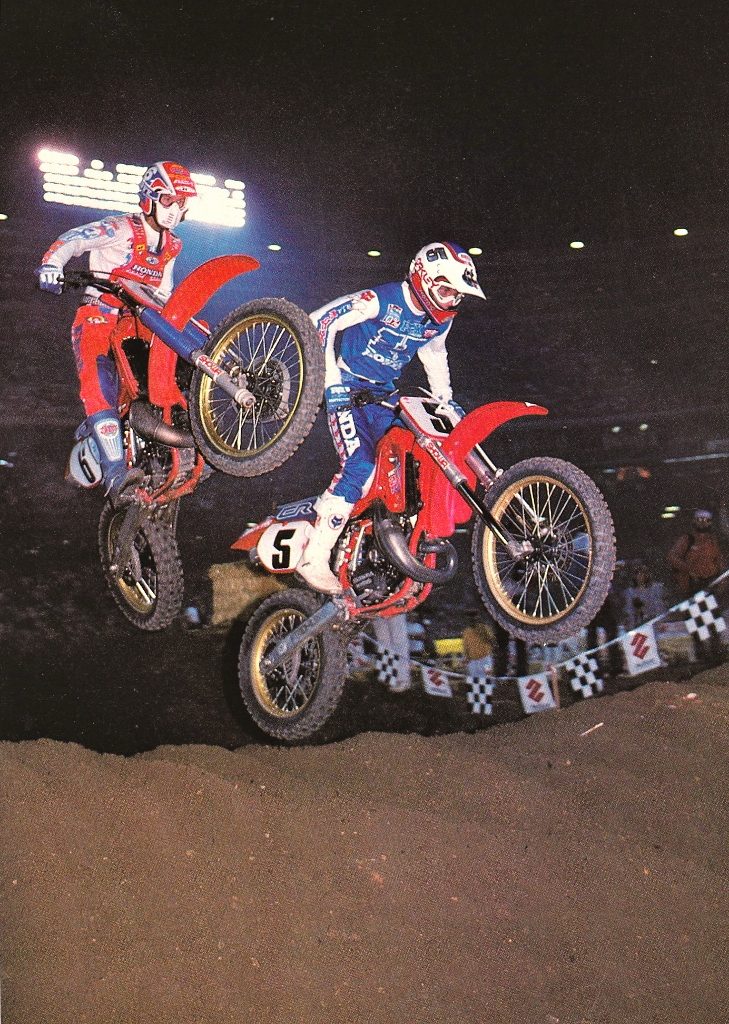

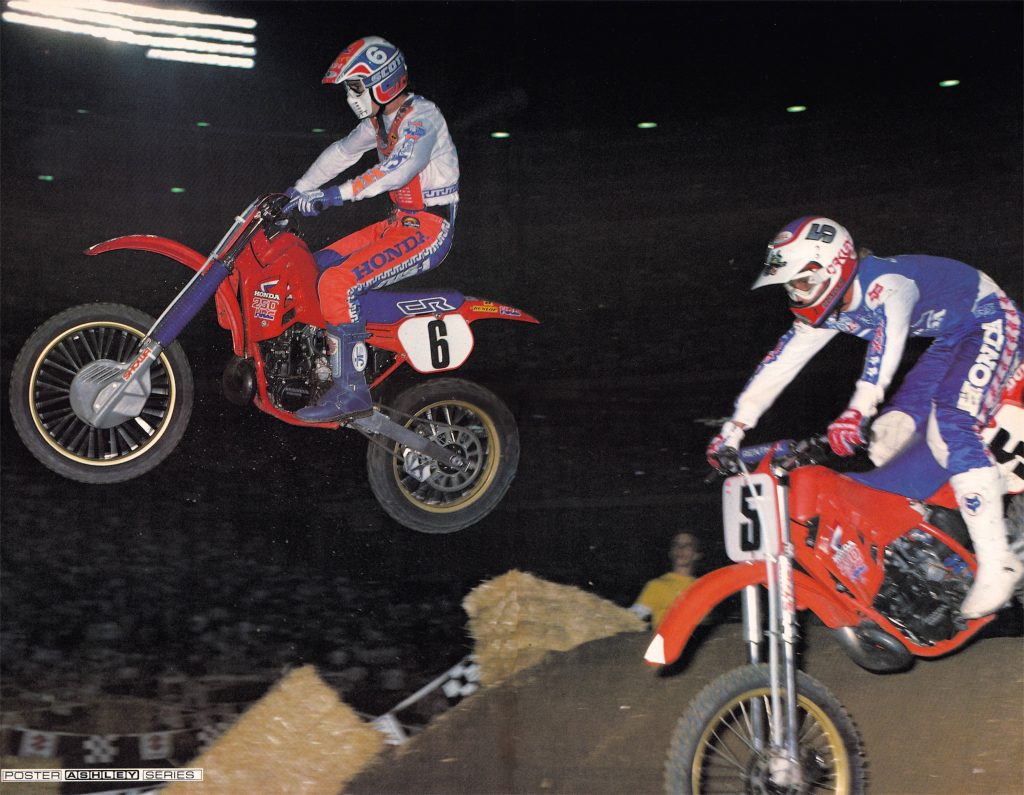

In 1986, Johnson alternated between running a works version of the stock 43mm conventional cartridge forks and a prototype of Showa’s new inverted versions. In this picture from the historic Anaheim Supercross, you can see that Johnson chose to run the USD forks, while Bailey elected to stick with the standard conventional versions. Photo Credi: Motocross Action

While stock looking in outward appearance, the works versions of the Showa’s conventional forks featured ultra-light magnesium sliders and special works internals for improved performance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Full works: Johnson’s bike featured works Nissin disc binders front and rear. With the stock rear unit being a drum in 1986, this was a significant upgrade in performance. Both units front and rear featured sand cast magnesium calipers mated to specially-cut works rotors. The rotors alone were said to cost over $1000 apiece. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The switch to production-based bikes came at just the right time for Big Red. The early eighties had seen Honda turn out a very inconsistent run of production machines. While their Factory race bikes were without equal, their production machines often left a lot to be desired. One year they would be the class of the field, while the next they would bring up the rear. In 1986, that cycle was on the upswing with an incredible lineup of machines that completely dominated the competition. The production CRs started out head-and-shoulders better than the competition, and with a little HRC massaging, they were all but unbeatable.

Because the production rule prohibited the use of works swingarms, Honda had to modify the stock one to accept the works rear disc brake in 1986. Ultra-light magnesium works hubs saved weight for performance and increased strength for safety. Photo Credi: Motocross Action

Because the production rule prohibited the use of works swingarms, Honda had to modify the stock one to accept the works rear disc brake in 1986. Ultra-light magnesium works hubs saved weight for performance and increased strength for safety. Photo Credi: Motocross Action

The ’86 works CR250R used the production Honda frame mated to works suspension front and rear. Slight modifications could be made for strength, but the basic frame had to retain the stock machine’s geometry and overall dimensions. At some races, Johnson experimented with works Showa upside-down forks while at others he went back to the conventional Showa cartridge units. For supercross, Johnson ran a slightly shorter shock to lower the rear of the bike for improved handling. The motor, while based on the stock Honda Power Port mill, featured different porting, reshaped exhaust valves and a custom piston. The crankshaft, was a HRC part and was perfectly matched and balanced to the cases. The resulting motor was incredibly smooth while also being blazing fast. Johnson could switch between pipes based on track conditions. For Supercross he usually ran a custom Pro Circuit pipe which provided excellent bottom and mid-range power. Outdoors, he preferred to run the HRC pipe which provided a more brutal hit and a screaming top end pull. The transmission gears could also be altered for durability and to fine-tune the gearing to the track conditions. The most noticeable visual difference from stock on the RC250 was probably the custom fabricated rear disc brake. Other than that, Johnson’s Honda looked very close to a stock CR250R.

The bodywork on the RC250 was all production parts with the exception of the Technosel seat and a $300 HRC front number plate. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The bodywork on the RC250 was all production parts with the exception of the Technosel seat and a $300 HRC front number plate. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Each team rider started out the year with two works machines prepped by HRC in Japan. From there, they could alter things like the seat, footpegs, handlebars, clamps and hand controls to customize the bike for each rider. Although all the team’s bikes started out virtually the same, they could end up very differently by the time the mechanics were done tweaking everything. It was this endless fine-tuning and attention to detail that really separated the factory bikes from the production machines. Even though in theory, everyone started the season on an even playing field, Honda always went that extra step to give all of their riders an advantage over the competition.

RJ was a much better rider on the Honda than he had been on his Yamaha. Something about the new team and bike transformed Johnson into a winning machine. He would dominate motocross for nearly four more years until an unfortunate accident with Danny Storbeck would leave him with a badly broken wrist and no hope of regaining his former glory. Photo Credit: Paul Buckley

RJ was a much better rider on the Honda than he had been on his Yamaha. Something about the new team and bike transformed Johnson into a winning machine. He would dominate motocross for nearly four more years until an unfortunate accident with Danny Storbeck would leave him with a badly broken wrist and no hope of regaining his former glory. Photo Credit: Paul Buckley

In some ways, the production rule actually ended up helping Honda. The ’85 RC250s, while incredibly trick, were acknowledged to be hard-to-ride beasts. The test riders had loved the bikes in preseason testing but found them hard to handle on the track. The switch to the production machines yielded a much package that proved unbeatable on the track. RJ would go on to capture a total of six AMA SX and MX titles on his production Hondas. It would probably have been even more, if not for him sustaining a broken wrist while holding a commanding lead in the ’89 Supercross series. Even though the injury would eventually end Johnson’s career, a continuous string of up-and-coming red riders waited in the wings to take his place at the front of the pack. After the advent of the production rule, Honda captured nine out of the next ten Supercross titles. Ironically, the rule that was supposed to derail the mighty Honda team, seemed to propel them to even greater success.

Here is another picture from Johnson and Bailey’s amazing 1986 Anaheim battle. In this race, the two Honda stars swapped the lead back and forth numerous times in one of the greatest battles of all time. Photo Credit: Tom Riles

The factory Honda CR250R you see here was actually David Bailey’s works bike. Of the two CR205Rs that RJ used during the ’86 season; only one remains. The first one was crushed by Honda in Japan and the second one was sent to Europe for testing, before finding its way to well-known collector Terry Goode. Since Bailey’s bike was virtually identical to Johnson’s, Honda merely switched out the number plates when the bike was presented to Johnson as a retirement present in 1991.

In 1986, works or production, nothing was as dominant as Honda’s awesome CR250R. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

1986 signaled the end of an era in American motocross. The age of the ultra-exotic Factory machine was over, replaced by stock looking bikes that hid their secrets below plain looking wrappers. As the bike that took so many legends to motocross glory, the ’86 RC250 will always be remembered as the greatest of these first generation production racers.