For this edition Classic Steel we are going to step into the motocross Wayback machine to take a look at one of most infamous Open class machines of the eighties, the Honda 1984 CR500R.

In 1984, Honda took a major gamble with their new CR500R, a gamble that in the end, did not pay off. Confused jetting and poor setup made the big Honda a handful for riders of any skill level. Photo Credit: Honda

The eighties were a very tumultuous time for Honda’s motocross efforts. During the decade of Reagan and Rambo, the Big Red Machine enjoyed both the champagne of victory and bitter ignominy of utter failure. In 1981, Honda had unveiled one of the most anticipated motocross machines of all time, the CR450R. After half a decade of success on the Grand Prix and American motocross stage, and huge a wave public anticipation, Honda finally offered a true-to-life Open bike to the buying public. Unfortunately for Honda fans, however, the revolutionary new machine turned out to be a colossal disappointment. Overweight, underpowered and unreliable, the ’81 CR450R was perhaps the worst Open bike out of Japan since the infamous Suzuki TM400 Cyclone.

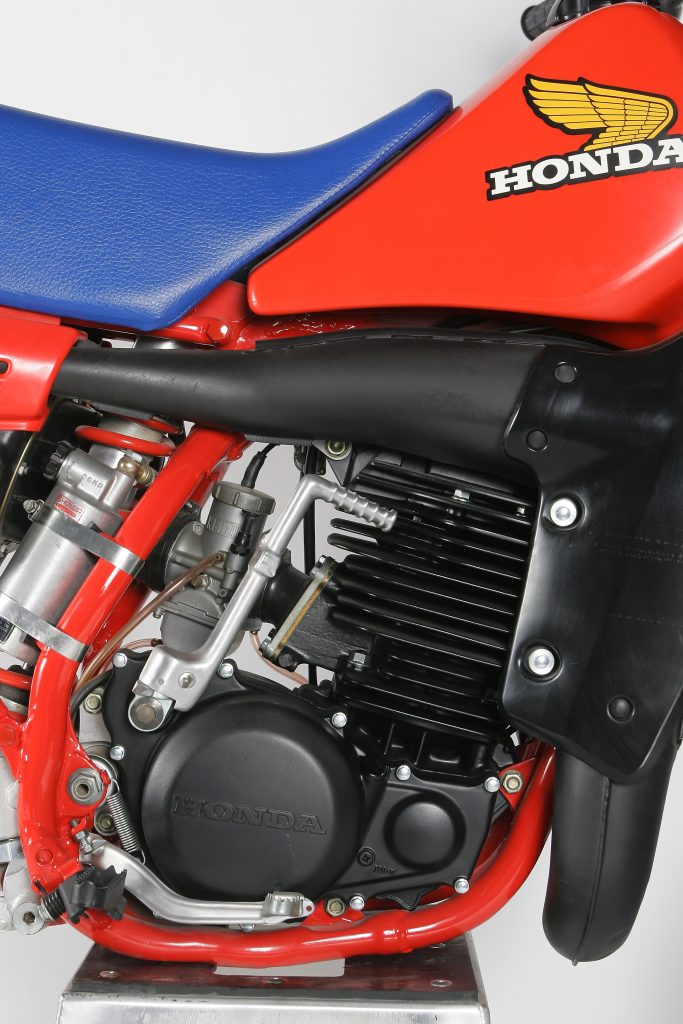

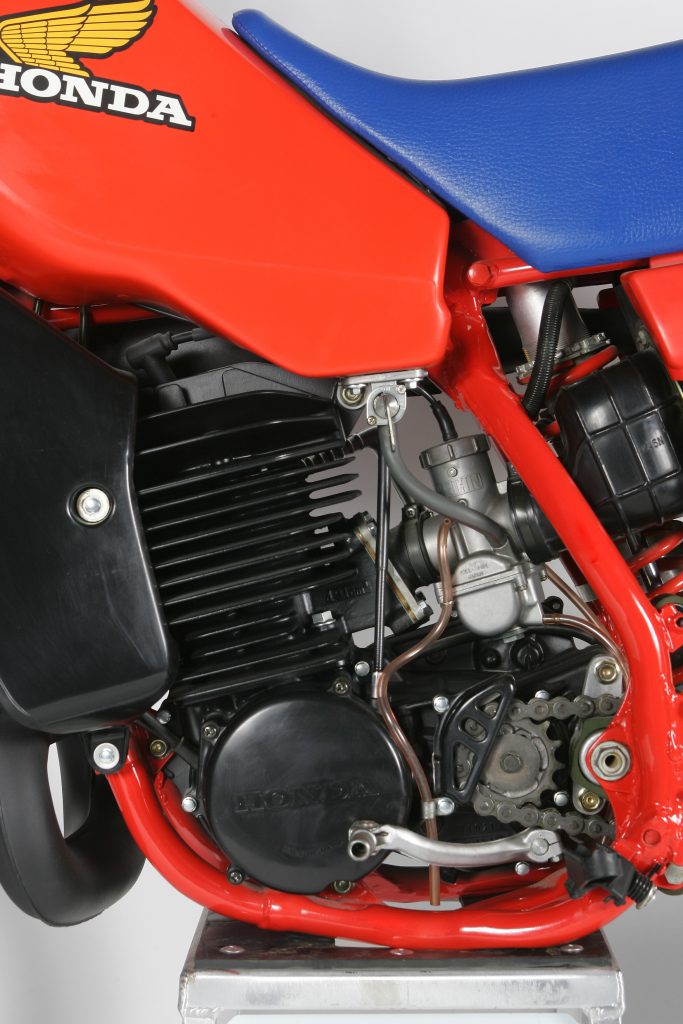

One and done: For ’84, Honda scrapped their successful CR480R motor and spec’d out an all-new 491cc mill. The new power plant stuck with air-cooling but featured lower cases clearly designed to accommodate water-cooling. The new motor would last but one year and be replaced with an all-new liquid-cooled mill for ’85. Photo Credit: Stephane LeGrand

Stung by the scalding reviews of ’81 and inspired by the wisdom of Roger De Coster, Honda came back with guns blazing in 1982. The ’82 CRs would be the first production machines to really benefit from the input of The Man and they would turn out to be a huge improvement over the woeful 1981 models. A new brawnier power plant, improved suspension, and sharper handling would highlight the reborn CR480R. After serving as the 500-class punching bag in ’81, red riders ended up doing the punching in ’82.

After dominating the standing with their awesome CR480R in 1983, Honda upped the ante for ’84 with an absolute bruiser of a machine. The new CR500R proved faster, but not nearly as effective on the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

After dominating the standing with their awesome CR480R in 1983, Honda upped the ante for ’84 with an absolute bruiser of a machine. The new CR500R proved faster, but not nearly as effective on the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For 1983, Honda once again completely redesign their big-bore racer. The all-new machine featured a revised motor with a new five-speed gearbox (the ’81 and ’82 models had made do with four-speeds), redesigned bodywork, and a Supercross-inspired chassis. The works-replica bodywork featured revised ergonomics, a low-center-of-gravity tank, and an orange and blue color scheme that mimicked the look of the factory team from ’82. The ’83 CR480R took the standings by storm with its feather-light weight (lighter than many 250s of the time), easy-to-use powerband (Maico-like), sharp handling (Ginsu), and stellar looks. After seven years of development and countless hours of testing, Honda had finally developed the ultimate Open-class weapon.

While capable of massive thrust, the 491cc mill found in the CR500R left a good bit to be desired in most other areas. Poor carburation, constant detonation, suspect reliability, and inscrutable starting highlighted the list of grievances riders had with the new machine. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Broc Glover (1) and David Bailey (1 blue plate) enjoyed some epic duals in 1984 aboard their mighty 500cc machines. The mere fact that Glover could even stay in the same zip code on his production-based Yamaha against the exotic works Honda was a real tribute to his talent and determination.

The early eighties were a truly unique time for motocross, where it was not uncommon for the manufacturers to completely redesign their bikes every year. For Honda, the ’84 CR500R marked the fourth all-new Open-class CR in as many years and a radical departure from its successful progenitor. Gone was the torquey 472cc mill that had captured rider’s hearts the year before, to be replaced with an all-new fire-breathing 491cc mega-motor. The new power plant shared not a single part with the outgoing mill and marked Honda’s departure from their infatuation with the traditional European left-hand kickstart. In addition to the new motor, the ’84 CR500R featured an all-new frame, a new disc front brake, completely redesigned bodywork, revamped suspension and a name change from 480 to 500.

Ram scoop: Although the ’84 CR500R retained the ’83 model’s air-cooling, it did pick up a set of large air scoops on either side of the motor to help keep the temps down. Even with these additions, however, the big 500 ran extremely hot and suffered from chronic detonation. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While the entire bike was all-new for ’84, by far the biggest news was Honda’s decision to plus size their big-bore mill. Starting in the late seventies, all the manufacturers had been steadily increasing the displacement of their Open class machines. In 1976, a 360 was considered a big bore monster, by ’84, all the manufacturers were bumping up against the 500cc mark. As these Open class beasts became more and more powerful, it became even more vital that the power they made was manageable. This was the key to the success of bikes like the Maico 490 and CR480R. Yes, they pumped out loads of horsepower and torque, but they did it in a way that made them (relatively) easy to control and fun to go fast on. In Open class racing, it was most often the quality of the power, not the quantity that made the difference between a winner and a loser.

The incredible Mr. Magoo: In 1984, it took the talent and bravery of a rider like Danny Chandler to get the most out of Honda’s hairy-chested half-liter. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1984, Honda decided to scrap their successful ’83 mill and started fresh with an all-new motor design. The new engine retained the air cooling of the previous motor but scraped all other vestiges of its award-winning progenitor. The redesigned power plant featured an 89mm x 79mm bore and stroke which bumped up the displacement from 472cc to full 491cc. Carburation was handled by a 38mm round-slide Keihin which fed the cylinder through a traditional reed-valve intake. The motor maintained a traditional porting layout and eschewed any sort of variable exhaust valve or sub-chamber. Without the ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) resonance chamber built into the exhaust manifold like its smaller ’84 Honda siblings, the 500 was both easier to service and cheaper to manufacture.

While Joe Schmoe was stuck hanging on for dear life on the stock CR, David Bailey got to ride this priceless piece of moto exotica. In 1984, there could not have been a bigger discrepancy between the haves and the have-nots of motocross.

While Joe Schmoe was stuck hanging on for dear life on the stock CR, David Bailey got to ride this priceless piece of moto exotica. In 1984, there could not have been a bigger discrepancy between the haves and the have-nots of motocross.

In 1983, the one complaint most riders had with the CR480R was with its relative lack of top-end power. It was very strong from the low-end through the midrange but very pedestrian on top. If you revved it out, it fell off sharply and keeping it in the low-to-middle part of the powerband was by far the best way to go fast on the red ripper.

In 1984, these 43mm Showa’s were considered state of the art with their adjustable compression damping and beefy sliders. Unfortunately, they were also softly sprung and too light on compression and rebound control. Major moolah was necessary to get the CR’s forks up to snuff in ‘84. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1984, these 43mm Showa’s were considered state of the art with their adjustable compression damping and beefy sliders. Unfortunately, they were also softly sprung and too light on compression and rebound control. Major moolah was necessary to get the CR’s forks up to snuff in ‘84. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

For 1984, Honda’s engineers went looking for a wider spread of power in their Open class machine. They hoped to spread the power out slightly while maintaining the solid low-to-mid power of ’83. In that endeavor, they were only partially successful. The new motor did indeed rev slightly farther, but most of its gains were in the midrange where the new bike pulled with ferocious authority. Low-end power was slightly less responsive than ’83, but much of that probably do to the bike’s poor carburation. In stock condition, the CR burbled down low and pinged on top. On hardpack, the pinging was not too objectionable, but in deep sand or loam, the bike developed a sever death rattle. If you tried to jet out the burble, then the rattle got worse and the bike threatened to detonate itself to death. At the time, the smart mods were to run race gas, have the head modified (or run two head gaskets in a pinch), and swap out the stock Keihin carb for a Mikuni mixer.

In 1984, Honda offered the best detailing in the business. Items like this sweet rebuildable alloy silencer and fully-removable rear subframe had the competition covered. Photo Credit: Stepan LeGrand

In 1984, Honda offered the best detailing in the business. Items like this sweet rebuildable alloy silencer and fully-removable rear subframe had the competition covered. Photo Credit: Stepan LeGrand

Once the jetting and head were fixed, the CR500R put out a brutally strong rush of low-to-midrange power. It was incredibly strong in the middle and most riders found it a bit too abrupt for their liking. Top-end power was strong, but as in ’83, short-shifting and using the torque was the best way to make time on the red beast. The five-speed transmission continued to be the smoothest shifting and most versatile in the class and the clutch was praised for its action and durability.

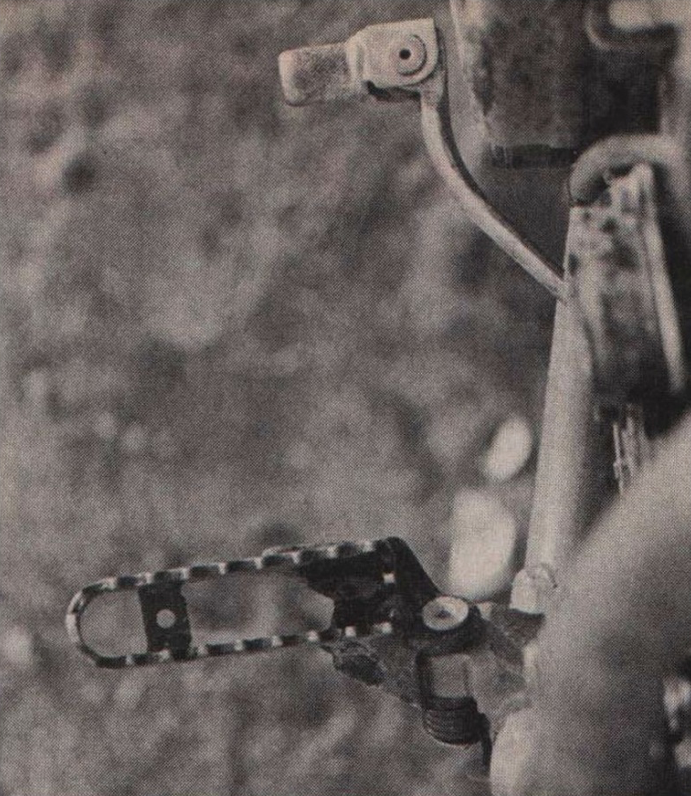

Would you believe this passed for the state-of-the-art in the footpeg business in the early eighties? Big news for ’84, was Honda’s lengthening of the pegs on all the full-size CRs. It would take another six years for Kawasaki to convince the world what you wanted was wider, not just longer. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Another area where the new machine turned out to be a step backward was in starting ease. On paper, the switch to right-hand kick seemed to indicate that things would be easier for ’84, but the new mill proved to be much more stubborn than previous Honda 500s. The new kickstarter was nice and long but placed very high on the chassis. This made it hard for anyone below 5’11” to get a good kick without finding a hill or a milk crate to stand on. Even if you could get a good swipe at the starter, however, there was no guarantee the big single was going to light. Cold or hot, it was a several kick affair and no amount of tricks or drills seemed to make any real difference. Sometimes it would light, and sometimes it would not, and the only real hope you had was to say a prayer, invest in some good boots, and practice your squats.

In 1984, none of the 500s available was the perfect Open class weapon. The RM500 offered suspension finesse but lacked for power (compared to the others) and suffered from stone-age braking performance. The Honda was incredibly trick and powerful but hit too hard, was jetted atrociously, and offered dismal suspension performance. The Yamaha ended up featuring the most competitive overall package but it was still saddled with a motocross-only four-speed gearbox, fragile wheels, blubbering jetting and pogo forks. Photo Credit: David Gerig

In 1984, none of the 500s available was the perfect Open class weapon. The RM500 offered suspension finesse but lacked for power (compared to the others) and suffered from stone-age braking performance. The Honda was incredibly trick and powerful but hit too hard, was jetted atrociously, and offered dismal suspension performance. The Yamaha ended up featuring the most competitive overall package but it was still saddled with a motocross-only four-speed gearbox, fragile wheels, blubbering jetting and pogo forks. Photo Credit: David Gerig

On the handing front, the ’84 CR500R was far more successful. Overall chassis feel was very similar to the ’83 CR with sharp turning and a very light feel. Even though the YZ490 was the lighter on the scale, the CR felt nimbler due to its excellent ergonomics and responsive handling. In the turns, the big CR could cut under many 250s and had no peers in the tighter sections of the track. Unfortunately, the trade-off for this agility was a vicious set of the shakes. When coming down from speed, the CR developed a nasty oscillation that could easily transform into a death-defying lock-to-lock affair. For motocross, this was probably a justifiable tradeoff but any sort of desert work you were going to want to invest in a steering stabilizer and a St. Christopher medal.

Shock performance was a major weak spot on early eighties Hondas. While the basic design of the Pro-Link worked well, the Showa shocks they employed were underdamped, fade prone and unreliable. Because of their poor build quality and short life-span, it was more practical at the time to go with an aftermarket alternative than spend money trying to make the stock damper function properly. Photo Credit: Honda

On the suspension end of things, the CR ended up taking a step back from 1983. Although far from perfect, the ’83 CR480R’s suspension package had at least been workable out of the crate. For 1984, that was no longer the case. The new 500’s 43mm Showa forks were undersprung and underdamped for the bike’s weight. On hard landings that crashed to the stops with a harsh metal-to-metal clank. Even with adjustments for air pressure and compression damping available, the CR wallowed in turns and bottomed in the rough. In the ’84 suspension rankings, only the YZ490’s pathetic Kayaba forks were worse.

Probably the only item on the ’84 CR500R that was actually a major improvement over ’83 was the front brake. This dual-piston Nissan stopper offered the excellent feel of the old drum unit (unlike the powerful, but grabby Kawasaki), but mated it to works-level pucker power. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Unfortunately for prospective buyers, the CR500R’s Showa shock was no better than its disappointing forks. While it offered a dizzying array of adjustments (17 compression and 22 rebound settings), none of them did much to improve its lackluster performance. Undersprung and badly underdamped, the Showa unit was completely overwhelmed by the bikes immense power and weight. Just like the ’83 unit, the damping went from light to nonexistent within a few minutes of hard use. Also like the ’83 shock, the hose running from the remote reservoir to the shock body also liked to blow off when the bike was ridden hard. Predictably, this did not do much to improve it already questionable action.

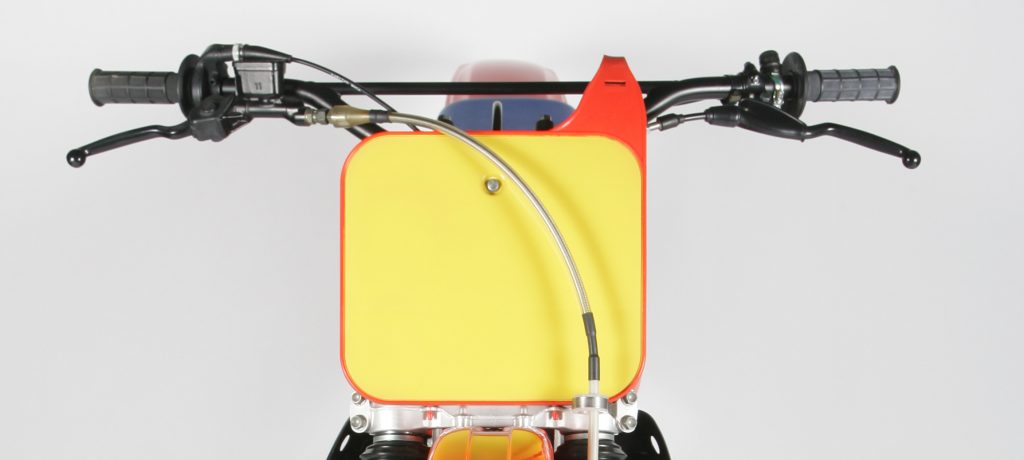

Today, we take things like quality grips and levers pretty much for granted, but in the eighties, there was a huge difference in quality between the brands. Honda had by far the best grips (the only ones actually good enough to leave on the bike), good quality steel bars (that actually lasted past the first tip over) and strong, forged dog leg levers that were both comfortable and immensely stronger than the cast alloy levers found on the yellow and green competition. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While the CR may have been a bit deficient in the suspension and motor civility department, the rest of the bike was zoot capri all the way. The addition of a powerful Nissin front disc gave the CR by far the best brakes in the class. The bodywork, ergonomics, and build quality were all head and shoulders above the other 500s at the time, with high-quality components and flawless fit and finish. While most of the components were durable, points had to be deducted for the motor and shock which were both prone to have issues. The horrible jetting and detonation were both annoying, but if left unchecked, both could lead to expensive failures. Cracked pistons and crank failures were common on CRs that were pushed hard and anyone serious about racing the bike would have been wise to address the carburetor and head issues.

In 1984, Honda tried to improve on their ’83 success with bigger and brawnier version of the class-leading CR480R. While it certainly looked the part, the new CR500R turned out to be a much less successful version of the bike it replaced. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1984, Honda took a major gamble redesigning its award-winning CR480R. It was a bike loved by the public and press alike, in spite of its flawed suspension and lack of top-end rev. For ’84, Honda started from scratch and ended up with a bike that was more powerful but far less effective on the track. Too powerful, too hard to start, and too poorly suspended, the ’84 CR500R was exactly the sort of big-bore brawler that sent riders cowering back to the 250 class. If you got the head fixed, the forks re-valved, the shock swapped and the jetting sorted, you had one hell of a potent machine, but in stock condition, you mostly had an unfished product. For those who plunked down their hard-earned $2598 in hopes of an improved CR480R, the all-new CR500R turned out to be a bitter disappointment.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter – @TonyBlazier