For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at Honda’s all-new CR125R for 1985.

The 1985 CR125R marked the fifth all-new Honda tiddler in five years. Yeah, things were just different in the eighties. Photo Credit: Honda

The 1985 CR125R marked the fifth all-new Honda tiddler in five years. Yeah, things were just different in the eighties. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1985, Honda was far from the 125 powerhouse they would become a few short years later. While the CR125M Elsinore had turned the industry on its head in 1974, its subsequent follow-ups had failed to impress. The all-new YZ125 and RM125 quickly eclipsed the Elsinore’s performance and left the outdated Honda in their wake.

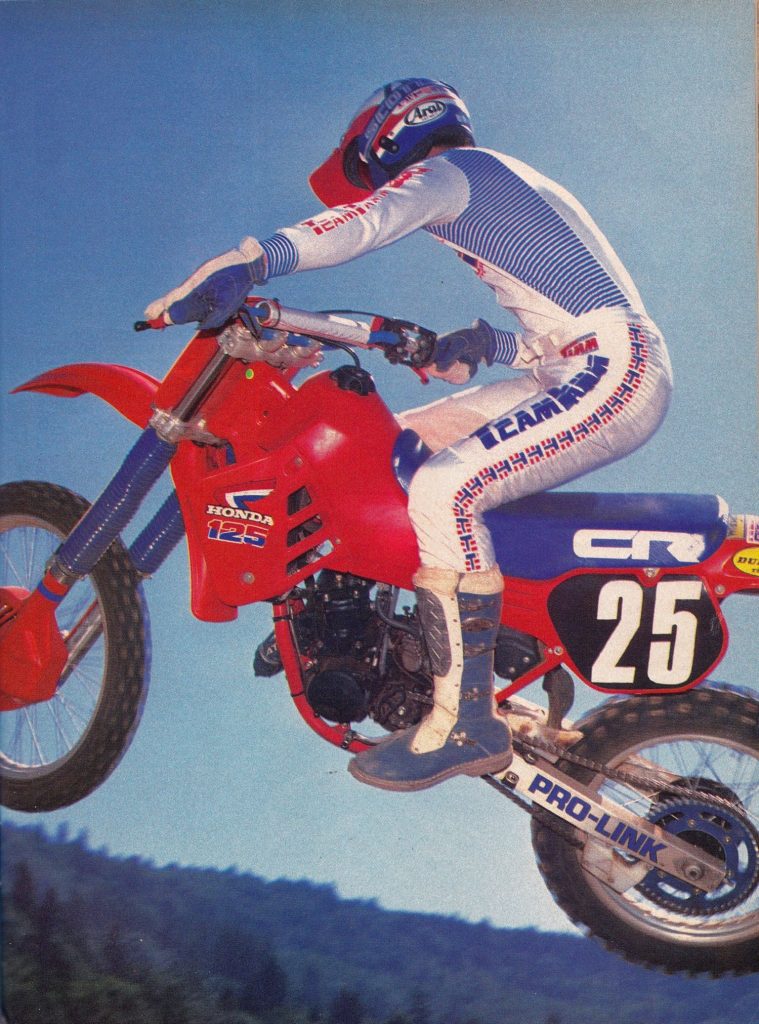

In 1985, Ron Lechien was Big Red’s hired gun in the 125 class. Even though the incredibly talented Lechien probably could have won on a stock CR (a feat he proved during his time with Yamaha), he was afforded the sizable advantage of riding Honda’s last true works 125 in America. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1985, Ron Lechien was Big Red’s hired gun in the 125 class. Even though the incredibly talented Lechien probably could have won on a stock CR (a feat he proved during his time with Yamaha), he was afforded the sizable advantage of riding Honda’s last true works 125 in America. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1981, Honda tried to snatch back the title of top 125 in the land with a radically redesigned CR125R. The new machine featured a laundry list of high-tech innovations and spacy styling, but once again proved to be a disappointment on the track. Two years later, Honda finally cracked the 125 code with an excellent all-around racer. The all-new ’83 CR125R handled and looked like a works bike, with sano styling and razor-sharp turning. The motor and suspension were not world-beating, but overall, the CR125R offered the most well-rounded package in the class.

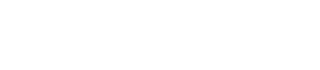

For 1985, Honda dialed up an all-new engine for their eighth-liter racer. A new crank added 3.3mm to the motor’s stroke and promised improved durability by replacing the previous motor’s plastic bushings with tougher alloy alternatives. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1985, Honda dialed up an all-new engine for their eighth-liter racer. A new crank added 3.3mm to the motor’s stroke and promised improved durability by replacing the previous motor’s plastic bushings with tougher alloy alternatives. Photo Credit: Honda

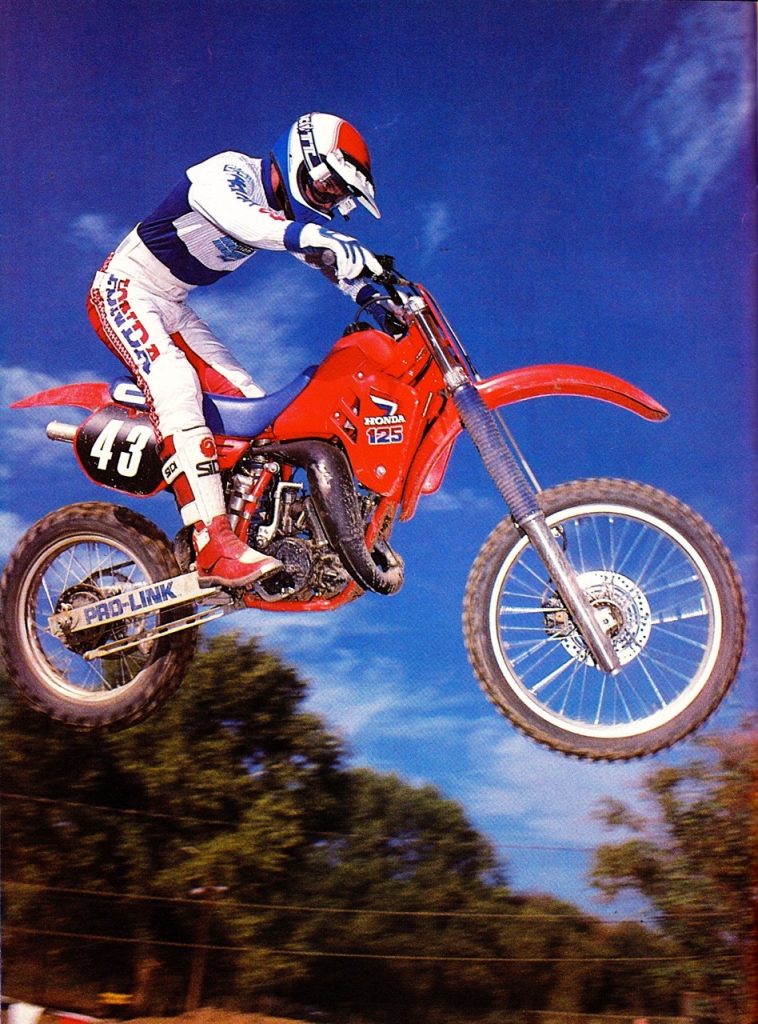

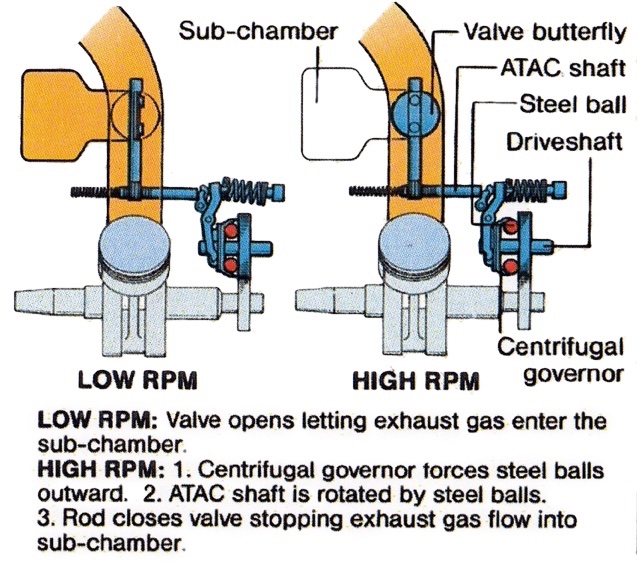

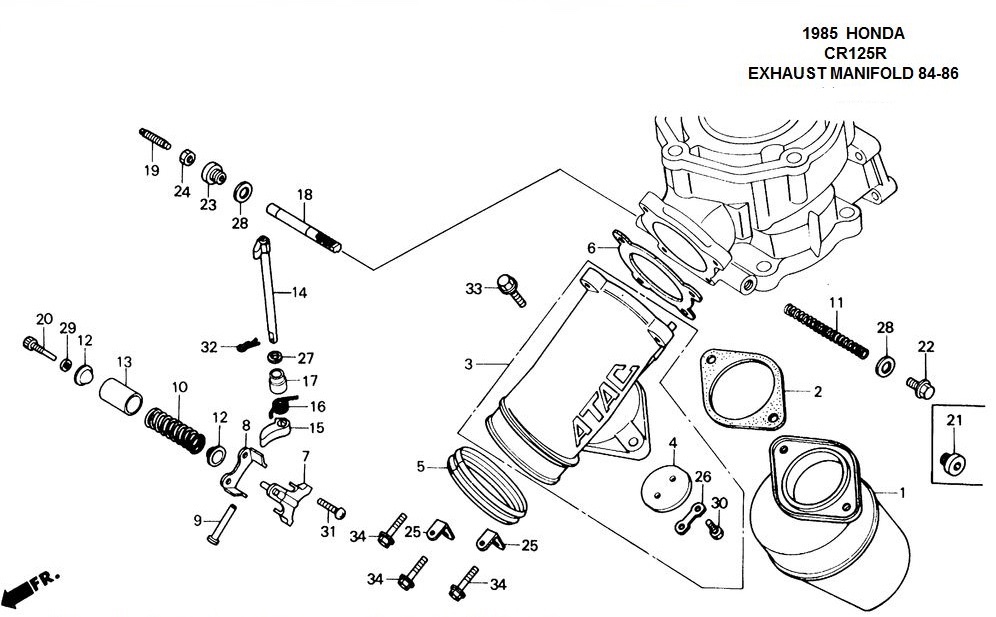

For 1984, Honda once again totally redesigned the CR125R (the fourth complete redesign in four years) and introduced the red brigade to works-style power through the introduction of the ATAC system. ATAC stood for Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber and consisted of a small sub-chamber off the exhaust port and a ball-ramp governor-controlled butterfly valve. The concept behind the ATAC was to boost low-end torque by increasing head pipe volume at low rpm, while still allowing proper flow at higher speeds for increased top end. In theory, the ATAC would allow engineers to have two separate expansion chambers at once; one tuned for torque and one tuned for top end.

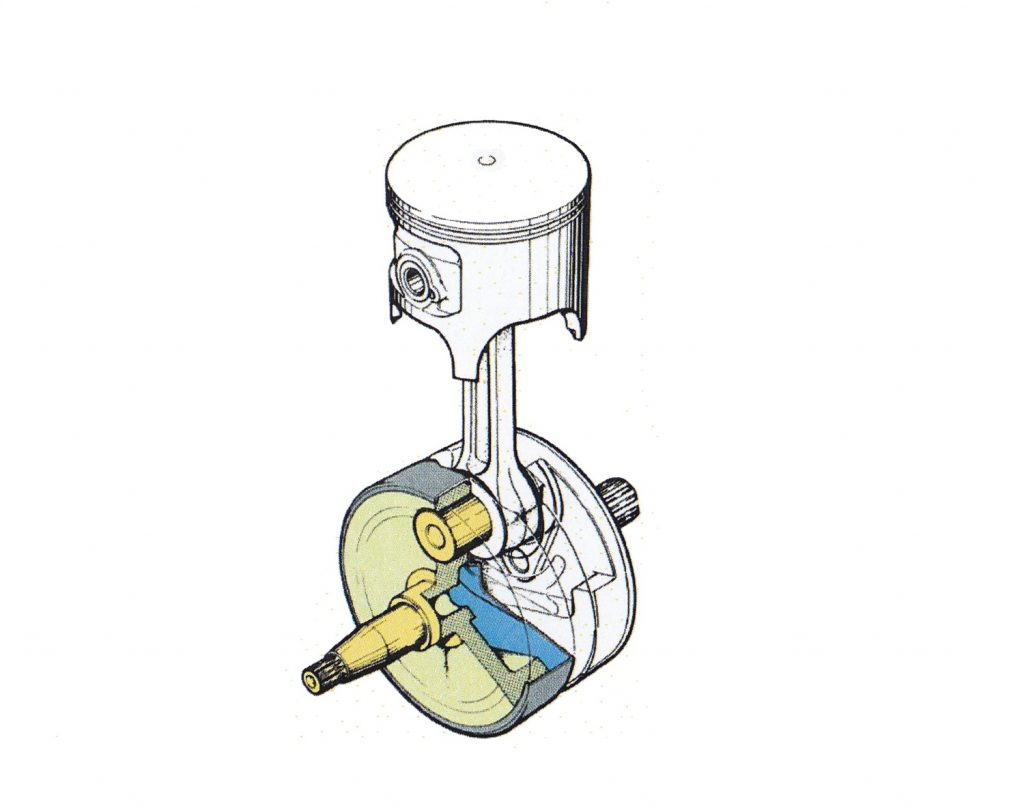

An all-new 34mm “flat-slide” Keihin carburetor promised better throttle response and more power for 1985. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new 34mm “flat-slide” Keihin carburetor promised better throttle response and more power for 1985. Photo Credit: Honda

While the theory behind the ATAC was sound, its early implementations turned out to be less than stellar. The 1984 CR125R was slightly torquier than its shootout-winning predecessor, but no match for Kawasaki’s quasar-fast KX125. Top end was sorely lacking and many tuners took to eliminating the ATAC altogether in search of more power.

The 1985 CR125R motor maintained the ATAC system of ’84, but paired it with an all-new top and bottom end. In 1984 there had been problems with pistons breaking, so for ’85 Honda added a bridge to the exhaust port to prevent ring-snagging. Displacement was also up slightly, with a longer stroke and slightly smaller bore than ‘84. Photo Credit: Honda

The 1985 CR125R motor maintained the ATAC system of ’84, but paired it with an all-new top and bottom end. In 1984 there had been problems with pistons breaking, so for ’85 Honda added a bridge to the exhaust port to prevent ring-snagging. Displacement was also up slightly, with a longer stroke and slightly smaller bore than ‘84. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1985, Honda looked to take back the crown they had owned in ’83 with yet another all-new CR125R. Nearly every component from 1984 was scrapped in search of more power, better handling and improved suspension. The shock, forks, frame, motor and bodywork were all-new and designed with the goal of overthrowing Kawasaki’s dominant position.

Aesthetics are certainly subjective, but I think there can be little argument that the new CR was one of the best-looking (the best IMO) bikes of 1985. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Aesthetics are certainly subjective, but I think there can be little argument that the new CR was one of the best-looking (the best IMO) bikes of 1985. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1984, the CR125R had been a very good bike saddled with a mediocre engine. In the 125 class, that was paramount to a death sentence and all the Honda’s other virtues were not enough to make up for this fatal deficiency. For 1985, Honda decided to stick with the ATAC, but reconfigured nearly every component in their eighth-liter power plant. Both the bore and stroke were new, with a 3.3mm longer stroke and a 1.5mm smaller bore for ’85. This resulted in a perfectly square 54mm x 54mm bore and stroke on the new mill. The crank was also redesigned, with new metal bushings replacing the problematic plastic components of ’84. The ATAC remained largely unchanged, but a new cylinder and head was added to accommodate the redesigned internal dimensions. Internally, the six-speed transmission was a carryover from ’84, but a new clutch was added and new magnesium cases replaced the aluminum components of the year before.

In stock condition, there were only two real power contenders in the 125 class of 1985. Both the Honda and Kawasaki offered broad midrange power that the yellow and white competition could not match. If not for the KX’s prodigious low-end grunt, we may have had a new powerband champion for ’85. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

In stock condition, there were only two real power contenders in the 125 class of 1985. Both the Honda and Kawasaki offered broad midrange power that the yellow and white competition could not match. If not for the KX’s prodigious low-end grunt, we may have had a new powerband champion for ’85. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Feeding the revised motor was a completely new 34mm PJ “flat slide” (oval slide technically) Keihin carburetor. The new carb replaced the brass round slide of ’84 with a new lightweight oval zinc unit that promised better airflow and improved throttle response. This new carburetor also featured a unique flared top that allowed the use of a conventional screw-on top and an innovative choke circuit that doubled as the bike’s idle-speed adjustment.

Introduced in 1984, Honda’s ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) took a different approach to broadening power than Yamaha’s YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System). The ATAC focused on the characteristics of exhaust flow, instead of altering port timing like the Yamaha system. Eventually, all the manufacturers would find the most effective design was actually a combination of both Honda’s and Yamaha’s setup. Photo Credit: Honda

Introduced in 1984, Honda’s ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) took a different approach to broadening power than Yamaha’s YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System). The ATAC focused on the characteristics of exhaust flow, instead of altering port timing like the Yamaha system. Eventually, all the manufacturers would find the most effective design was actually a combination of both Honda’s and Yamaha’s setup. Photo Credit: Honda

On the track, the new 123.7cc motor proved a solid, if not astounding improvement over the mellow ’84 mill. Low-end torque was down from the year before, but there was a much meatier midrange and greatly improved top end waiting once the ATAC kicked in. Out of corners, the bike was slow to rev and a good deal of clutch abuse was necessary to get it into the meat of the powerband. Once on the pipe, however, it pulled with authority through a solid midrange and into a decent top end hook. On top, the bike was happy to rev, but there was not a lot to be gained by screaming to the stops. Most of the usable thrust was found in the midrange and keeping it in this part of the powerband yielded the best results.

The ATAC system was far less complicated (and effective) than later Honda designs like the HPP (Honda Power Port). Photo Credit: Honda

The ATAC system was far less complicated (and effective) than later Honda designs like the HPP (Honda Power Port). Photo Credit: Honda

In terms of powerband hierarchy, the new CR fit well above the anemic YZ and top-end-only RM, but a notch below the brawny KX. It was both faster and broader than the two back markers, but not as outright powerful as the KIPS-equipped Kawasaki. The KX offered far more low end and midrange, with a similar pull on top. If it had offered more grunt, it could have given the KX a run for its money; as it stood, it was the second-best power package of ’85.

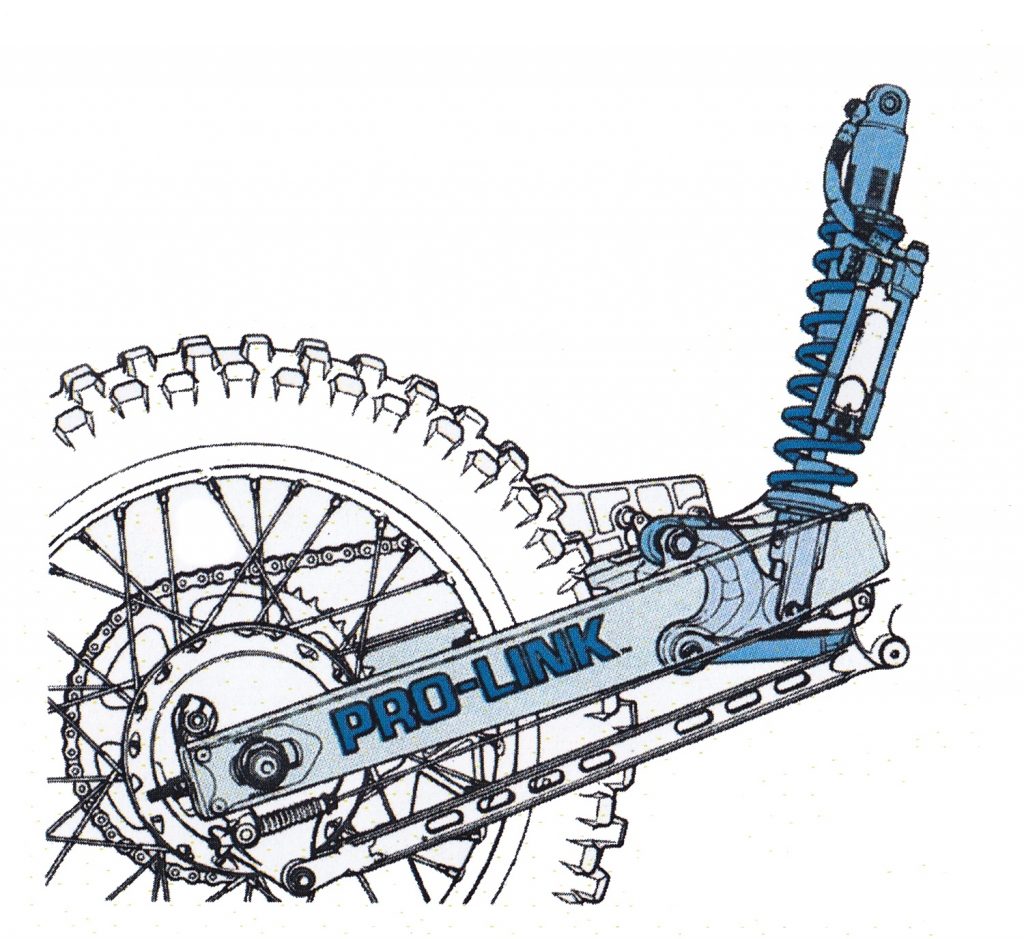

An all-new Pro-Link rear suspension for ’85 offered slightly more shock travel and a less-progressive linkage curve. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new Pro-Link rear suspension for ’85 offered slightly more shock travel and a less-progressive linkage curve. Photo Credit: Honda

On the chassis front, an all-new frame increased rigidity for ‘85 with a new boxed downtube and beefed-up steering stem. Geometry was also altered to better work with the new machine’s redesigned Pro-Link rear suspension. A new swingarm was bolted on and connected to a 10mm longer KYB shock and revised rising-rate linkage. As it had been since ‘83, the rear subframe remained fully removable (one of the only bikes in the class with this time-saving feature) and easily replaceable in the event of damage.

Rubber mounted bars lessened vibration. Photo Credit: Honda

Rubber mounted bars lessened vibration. Photo Credit: Honda

Up front, the new CR used a set of 43mm air-adjustable conventional Kayaba forks for the suspension duties. Interestingly, this was a departure from the Showa components found on the CR250R and CR500R. These KYB units offered 11.2 inches of travel and adjustments for compression, but no rebound adjustability. Still a year away from the introduction of cartridge internals, the CR’s KYB forks used traditional damper-rods for damping control.

One of the strengths of the ’85 CR125R package were its excellent Kayaba forks. Air-assisted and adjustable for compression damping (no rebound adjustment was available), these 43mm units were well set up and some of the best units in the class. Photo Credit: Honda

One of the strengths of the ’85 CR125R package were its excellent Kayaba forks. Air-assisted and adjustable for compression damping (no rebound adjustment was available), these 43mm units were well set up and some of the best units in the class. Photo Credit: Honda

In terms of suspension performance, the new CR was a bit of a mixed bag. Up front, nearly everyone praised the comfort and control of the Honda’s forks. The 43mm sliders were beefy, flex free (for the time) and well damped. The spring rates were spot-on for the average tiddler pilot and most riders could find a suitable setting without resorting to oil and valving changes.

The Machine: In 1985, Factory Honda’s Ronnie Lechien took his incredibly trick RC125 to his one and only National Motocross title. Photo Credit: Paul Buckley

The Machine: In 1985, Factory Honda’s Ronnie Lechien took his incredibly trick RC125 to his one and only National Motocross title. Photo Credit: Paul Buckley

Out back, the picture was less rosy. The new Pro-Link suspension was supposed to offer smoother action than in ’84, but its actual performance was little improved. The KYB shock offered adjustable compression and rebound damping, but no amount of adjustment seemed to calm its busy action. Under braking it hopped, chattered and kicked, and under acceleration it deflected instead of absorbing sharp hits. The spring rate and damping were too light for even someone of modest speed and any serious aerial work was bound to result in major burnt rubber on the underside of that lovely rear fender.

The rear suspension on the ’85 CR125R was not nearly as effective as the front. When new, it hopped, kicked, and generally did a pretty bad job of absorbing the track. Once a few hours were logged on it, that got appreciably worse as its fragile internals wore out in short order. Photo Credit: Honda

The rear suspension on the ’85 CR125R was not nearly as effective as the front. When new, it hopped, kicked, and generally did a pretty bad job of absorbing the track. Once a few hours were logged on it, that got appreciably worse as its fragile internals wore out in short order. Photo Credit: Honda

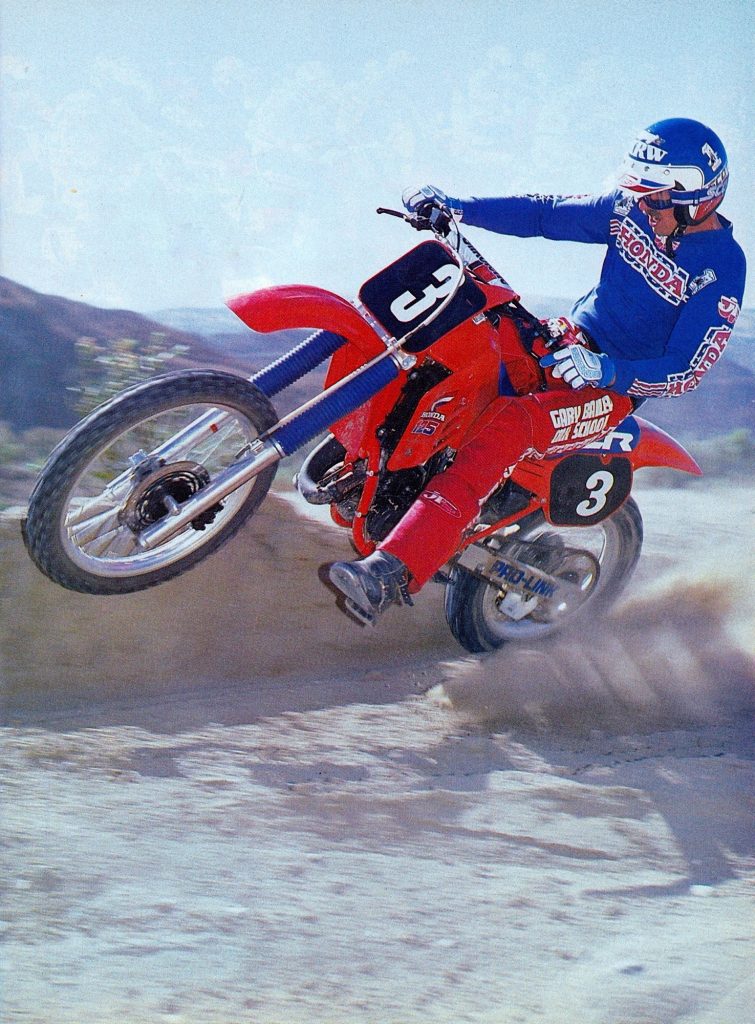

Pin it to win it: Here Gary “The Professor” Bailey displays the proper technique for extracting the most performance out of the new CR125R. Without a lot of power down low, a heathy dose of throttle and a quick fanning of the clutch were the only way to keep the KX in sight in ’85. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Pin it to win it: Here Gary “The Professor” Bailey displays the proper technique for extracting the most performance out of the new CR125R. Without a lot of power down low, a heathy dose of throttle and a quick fanning of the clutch were the only way to keep the KX in sight in ’85. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Perhaps most annoying of all was the shock’s suspect reliability. Without the benefit of hard anodizing on the shock body, the internals tended to wear out very quickly and within a few months of use, the CR damper was all but shot. In 1985, finding replacement parts to rebuild it was also nearly impossible and many savvy racers were forced to turn to more robust aftermarket alternatives.

Pure unobtanium: While the stock CR125R was no powerhouse, there could be little doubt that Ronnie Lechien’s full works RC125 did not suffer from the same deficiencies. The arrival of the Production Rule in 1986 would put an end to such exotica here in America. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Pure unobtanium: While the stock CR125R was no powerhouse, there could be little doubt that Ronnie Lechien’s full works RC125 did not suffer from the same deficiencies. The arrival of the Production Rule in 1986 would put an end to such exotica here in America. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

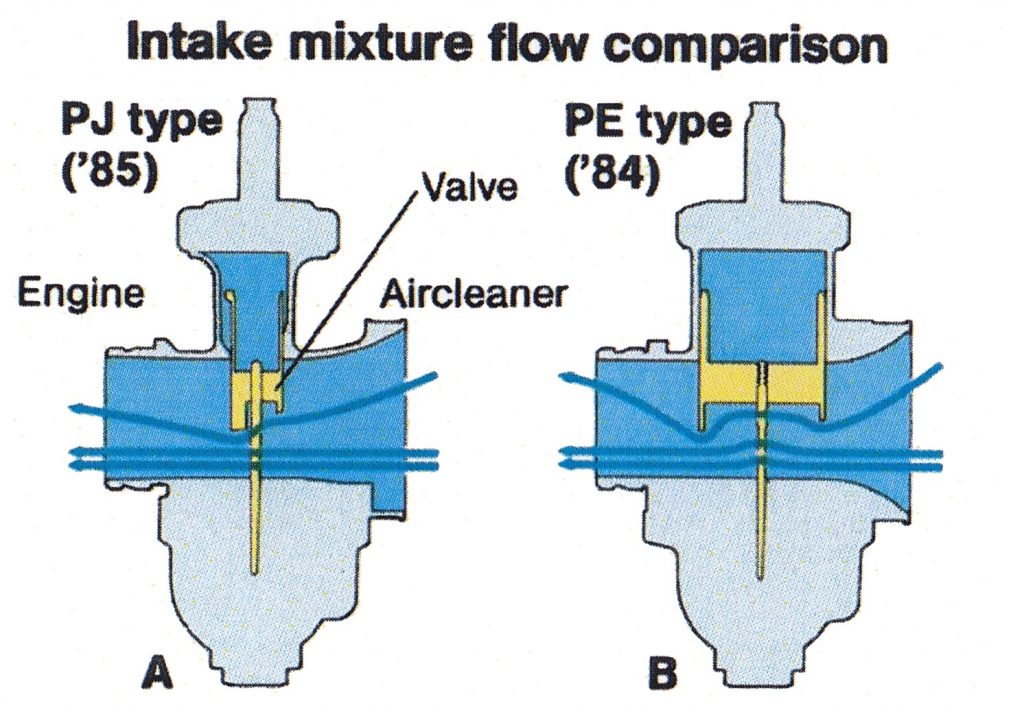

On the handling front, the CR was an absolute dream on tight circuits. With excellent ergonomics, streamlined bodywork, light weight and sharp geometry, the CR could literally cut under anything on the track. No line was too tight and no off-camber too tricky on the red scalpel. Jumping was also excellent and the Honda felt feather-light and maneuverable in the air. The flipside of this excellent cornering, however, was headshake violent enough to make you consider taking up table tennis.

The 124cc mill on the 1985 CR125R pumped out a competitive, but not omnipotent power curve. There was not a lot of torque down low, but a solid midrange and decent top end pull. Photo Credit: Honda

The 124cc mill on the 1985 CR125R pumped out a competitive, but not omnipotent power curve. There was not a lot of torque down low, but a solid midrange and decent top end pull. Photo Credit: Honda

At speed, the front of the bike never quite felt planted and under braking, the CR could oscillate the bars hard enough to rip your hands clean off the grips. In the days before OEM steering dampers, the smart (and free) setup was to cinch down the steering head nut just tight enough to feel a little bit of drag when turning. While this shade-tree damping solution probably shortened the lifespan of your bearings a bit, it did help to extend the lifespan of your BVDs.

If you were serious about racing the 125 class in 1985, there really were only two choices. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

If you were serious about racing the 125 class in 1985, there really were only two choices. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

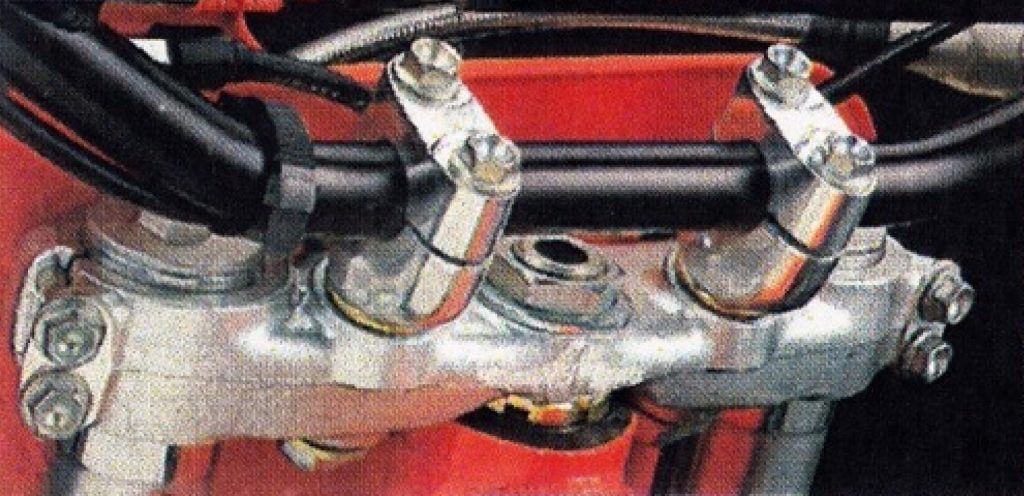

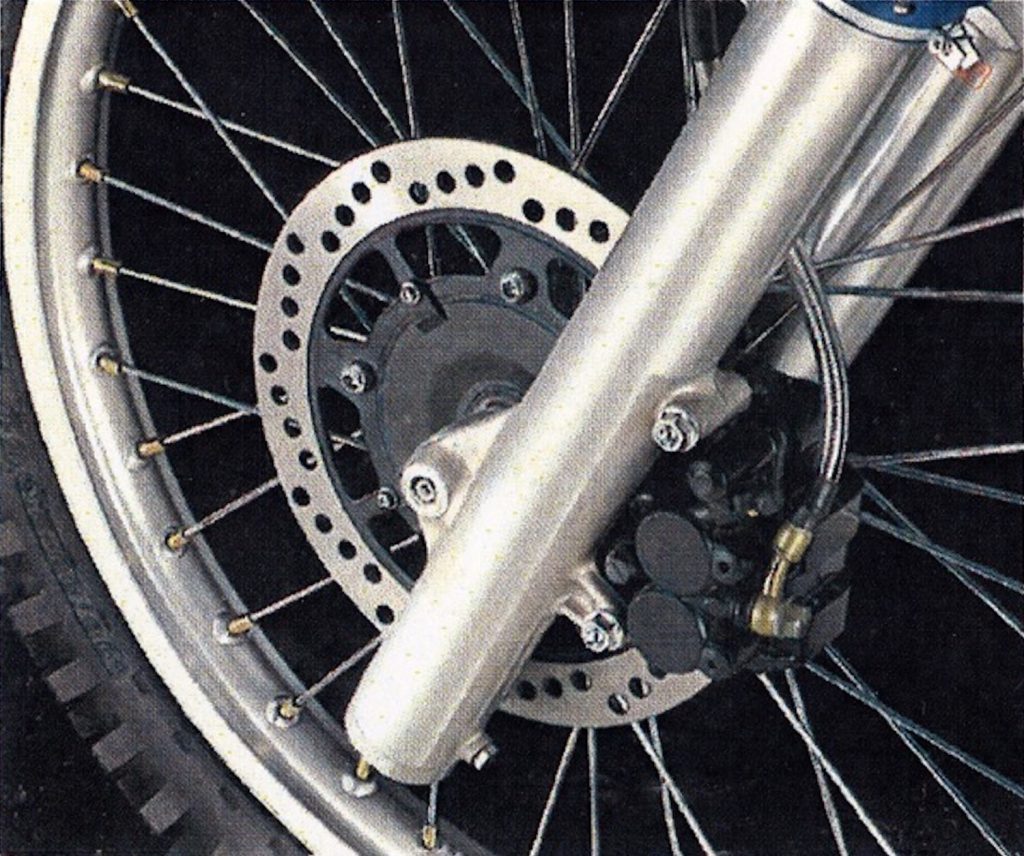

As with most bikes of its era, the ’85 CR125R was a mix of novel ideas and engineering missteps. On the plus side were the CR’s excellent front disc brake (by far the best in the class), slick shifting (the slickest), easy-pulling and durable clutch (bulletproof), great grips (the only ones in the class worth actually leaving on the bike), trick removable subframe (sano), and awesome looks. In the thumbs down category were the persnickety ATAC (dubious in effectiveness and tricky to keep working properly), wear-prone shock (pogo-stick, here we come), weak motor mounts (they stretched and often broke over time), wimpy chain and sprockets (Silly Putty was tougher) and squeaky rear drum binders (a switch to aluminum from magnesium for the shoe backing lessened the squeal, but did not exorcise it completely).

The 1985 CR125R was an excellent handler and a capable flier. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

The 1985 CR125R was an excellent handler and a capable flier. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Pucker power: The dual-piston Nissin front binder on the ’85 CR125R offered the most power and best feel in the class. Photo Credit: Honda

Pucker power: The dual-piston Nissin front binder on the ’85 CR125R offered the most power and best feel in the class. Photo Credit: Honda

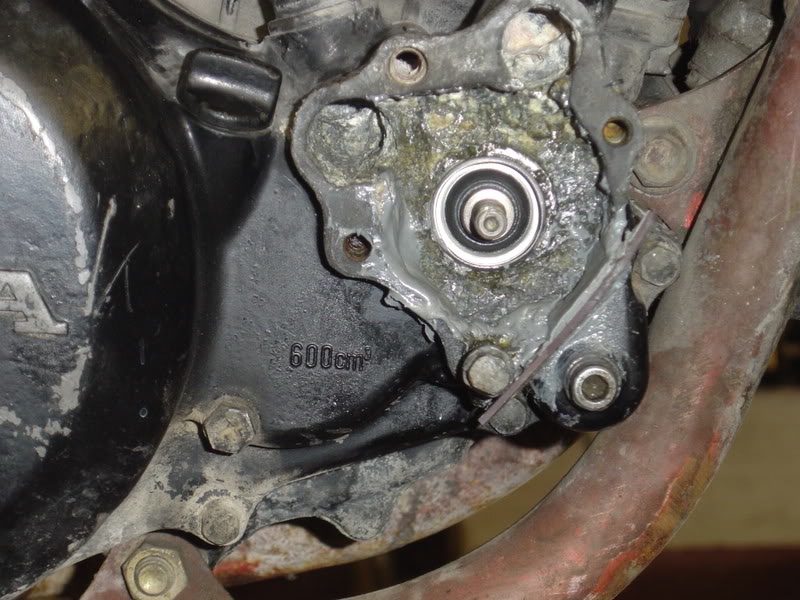

Ultimately, one of the CR’s biggest engineering faux pas was something that did not prove to be a problem until much farther down the road. For 1985, Honda decided to switch the engine cases on all the full size CRs from aluminum to magnesium. While this did not cause any immediate problems, anyone who has looked at restoring one of these mid-eighties CRs will be quite familiar with the effects coolant had on these magnesium components. Over time, that coolant would slowly turn from a liquid to a thick paste as the magnesium rotted away. If you let it go long enough, the entire coolant system would become clogged with this guck. Ugh…

All plugged up: In 1985, Honda switched from aluminum to magnesium for the engine cases. While not an issue initially, this switch led to serious corrosion problems down the line. Photo Credit: The World Wide Web

All plugged up: In 1985, Honda switched from aluminum to magnesium for the engine cases. While not an issue initially, this switch led to serious corrosion problems down the line. Photo Credit: The World Wide Web

While the 1985 CR125R did have its share of small annoyances, it was certainly no worse, and in many cases, much better than its competition. The Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha all offered far inferior build quality and overall workmanship to the red machine. In the case of the Kawasaki, it was incredibly fast, but prone to cracked frames, broken linkage arms and fractured plastic bits. Fit, finish, component quality and overall durability was a cut above on the Honda. None of the 125s of ’85 were perfect, but if you were looking for a bike that could take abuse and keep right on going, the Honda was an excellent choice (just remember to watch the shock and change that coolant regularly).

In 1985, Kawasaki offered the most power, Honda the best handling (as long as you were not afraid of a little headshake), Suzuki the best suspension and Yamaha the best…well, um…give me a minute, the best red fork boots in the class! Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1985, Kawasaki offered the most power, Honda the best handling (as long as you were not afraid of a little headshake), Suzuki the best suspension and Yamaha the best…well, um…give me a minute, the best red fork boots in the class! Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the final standings, the CR125R ranked just below the KX125 in most magazine’s shootouts. The Honda handled better, stopped faster and had superior forks, but lacked the meaty burst of the power-house Kawasaki. On a 250 or 500, its slight power disadvantage would not have been enough to outweigh its other virtues, but in the 125 class, power was everything. It was a solid bike, with a middling shock and moderately potent motor. For juniors and intermediates, the CR125R was a great machine, but for the true throttle jockeys, it was hard to overlook the massive power advantage Kawasaki had in ’85.

In 1985, Honda offered a very appealing package in the 125 class. For a cool $1948, you got a bike with solid power, excellent turning, great forks and stellar looks. It was not the most powerful bike on the track (no small demerit in the hotly-contested 125 division), but it offered a lot to love for someone averse to green. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1985, Honda offered a very appealing package in the 125 class. For a cool $1948, you got a bike with solid power, excellent turning, great forks and stellar looks. It was not the most powerful bike on the track (no small demerit in the hotly-contested 125 division), but it offered a lot to love for someone averse to green. Photo Credit: Honda

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com