For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to look back at Suzuki’s all-new RM125 for 1992.

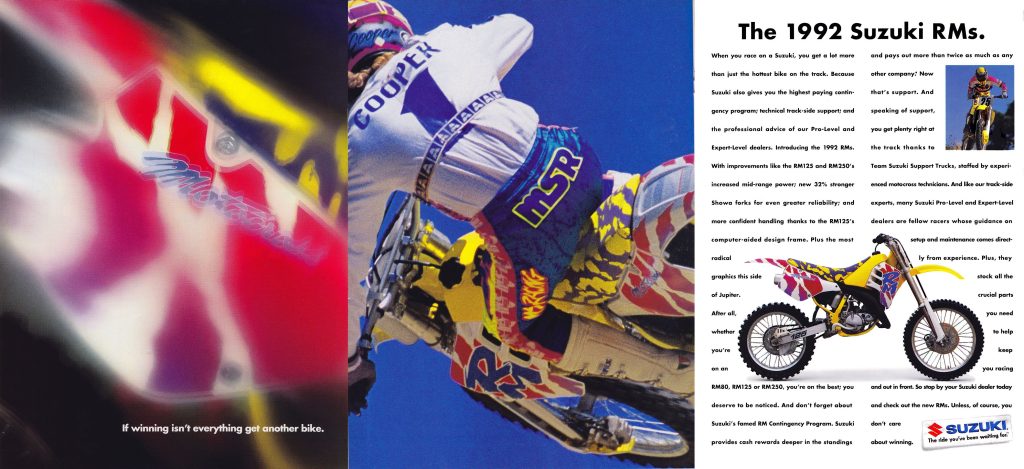

In 1992, Suzuki unveiled the most outlandish-looking line of motocross machines ever. Thankfully, underneath those clown-show graphics beat the heart of a winner. Photo Credit: Suzuki.

The early nineties were a great time to be riding a Suzuki in the 125 class. While the RM250s of this era were often polarizing in their appeal, the yellow 125s were largely praised for their lithe handling, light feel, and punchy delivery. More quick than fast, these RM125s got up and went at the slightest crack of the throttle and proved very effective on tight tracks with lots of jumps. On high-speed circuits, the RM lost out to Honda’s shrieking CR125R, but for many riders the little Suzuki’s brand of “right now” power made it the bike to own in the 125 division.

In 1989, Suzuki introduced an all-new RM125 that turned around the brand’s fortunes in the 125 class. While not the fastest machines available, the ’89-’91 RM125’s brand of snappy power, sharp handling, and supple suspension made them popular choices in the 125 wars of the time. Photo Credit: Suzuki

For Suzuki, this return to 125 competitiveness began in 1989 with the introduction of their all-new case-reed RM125. The new machine was a radical departure from previous designs and featured a stem-to-stern rethinking of their 125 platform. An all-new chassis greatly improved turning and redesigned bodywork improved ergonomics and transformed the RM from an ugly duckling to one of the prettiest bikes in the class. The new case-reed motor shelved the rev-happy powerband of 1988 in favor of a low-mid burst that made the bike far easier to ride. There was not a lot of power on top, but the RM was quick out of turns and super fun to ride.

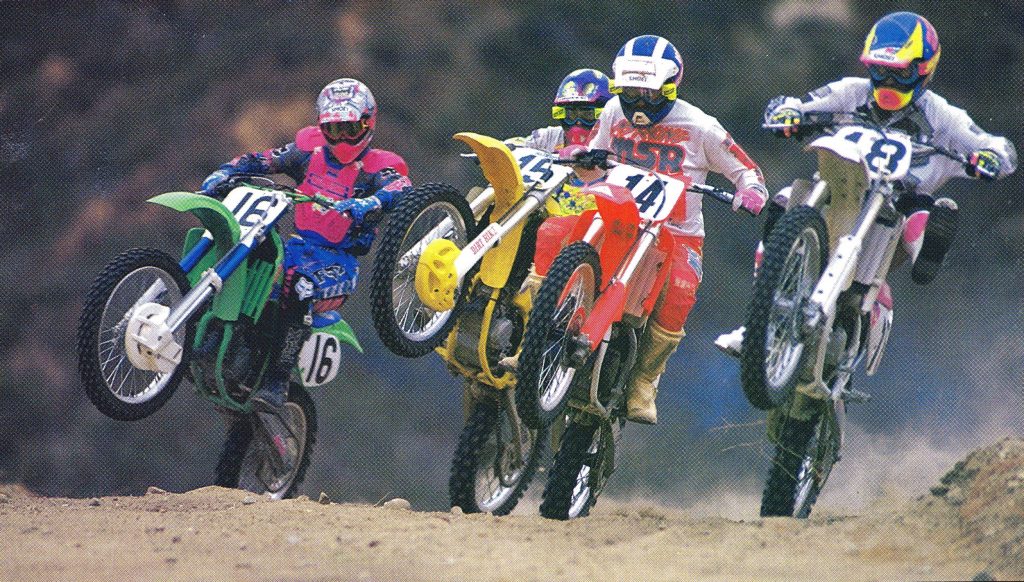

The 125 class of 1992 was certainly a colorful lot with only Kawasaki trying to display a little subtlety in its design. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Over the next two years, Suzuki refined their RM125 package with updates aimed at broadening its appeal. While novices loved the case-reed motor’s punchy powerband, experts found its lack of top-end pull frustrating. It was excellent at Supercross-style circuits, but less effective once the track opened up. The RM’s focus on turning also had its downsides with the machine delivering a busy and unplanted feel at speed. While many felt this was a fair tradeoff for the Suzuki’s excellent turning, more than a few riders wished for a bit less wander from the always-busy RM.

An all-new frame for 1992 moved to square tubing for much of the structure and featured increased gusseting and a larger swingarm pivot. According to Suzuki the new design offered a 25% improvement in flex resistance over the 1991. Photo Credit: Suzuki

After three years of refinement, Suzuki was ready to introduce the first major update to their case-reed 125 platform in 1992. In 1991, the RM had continued Suzuki’s run of very competitive 125s, but like the previous two years, not everyone had loved its brand of eighth-liter performance. The bike was very quick, but the powerband remained quite short and the suspension performance no longer topped the field. The bike still turned on a dime, but a propensity to wheelie out of every turn and headshake under power frightened more than a few 125 pilots into sampling red and green.

Say what you will about the styling, it would certainly be hard to ignore this three-page ad when you opened your new issue of Motocross Action. I’m not sure how many people liked the RM’s new look at the time (I certainly didn’t) but there can be little doubt that it helped the bikes stand out in the showroom. Photo Credit: Suzuki

For 1992, Suzuki looked to address all these concerns by totally redesigning the chassis and majorly reworking the motor on their RM125. The basic DNA of the 1991 motor remained, but Suzuki made several changes aimed at broadening power and improving response. In 1991, some RM125s had suffered from an annoying engine stutter in rough whoops and when landing from jumps. This was traced to issues with the intake tract, so Suzuki redesigned the entire intake for 1992. All-new lower engine cases straightened and smoothed out the lower intake and a new intake manifold shortened the overall distance the mixture had to travel. A new crank was added that featured slightly more weight to smooth out the power. This was paired with beefed-up gears for the primary and clutch drive for increased durability. A revised ignition produced a hotter spark for 1992 and an all-new exhaust offered a new shape designed to lower the center of gravity and provide a longer pull on top.

One interesting fact about the 1992 RMs is that not all of them looked the same. In markets outside of the US the ’92 machines maintained the all-yellow plastic of ’89-’90. While this was a cleaner overall look, I am not certain it actually works better with the over-the-top ’92 graphics. One other difference worth mentioning is the replacement of the word “Motocross“ with “Slingshot” on the side plates. This was a reference to the Mikuni “Slingshot” carburetor that Suzuki had helped develop for the RMs. For some reason, this carburetor always played a major role in advertising outside the US but never seemed to get more than a passing reference from American Suzuki. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The top end of the motor was less radically altered but small tweaks were made to work with the new flow characteristics of the revised bottom end. Carburation duties continued to be handled by Mikuni’s 35mm flat-slide “Slingshot” mixer, a fact that seemed significant enough to emblazon across the side panels of RMs in markets outside the US. For some reason American Suzuki never seemed particularly impressed with the marketing value of this special carb and chose to replace the “Slingshot” graphics with “Motocross” on the US-bound models.

In addition to the all-new frame the 1992 RM125 featured significant changes to the motor as well. An all-new bottom end shortened and straightened the intake tract and a redesigned crank added weight and increased durability. The clutch was new as well with larger plates for improved action and increased fade resistance. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In addition to the power upgrades, the RM’s motor received some additional enhancements aimed at lowering weight, easing servicing, and increasing durability. All-new side cases repositioned the water pump and coolant drain for easier access and a new magnesium clutch cover lowered the motor’s weight. The clutch plates were increased in size for 1992 and featured a new material for improved feel and increased longevity. The transmission remained a six-speed with ratios unchanged from 1991.

The appeal of the early nineties RM125s was their always-ready power. What the Honda accomplished with endless rev, the RM did with instant get-up-and-go. It was a style of power that made the bike fun and easy to go fast on. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the chassis front, the RM was even more radically updated for 1992. The complete 1991 frame was scrapped in lieu of an all-new design that Suzuki claimed offered a whopping 25% increase in rigidity over the year before. The new frame swapped the 1991’s oval tubes for an all-new square-tube design crafted out of tough chromoly steel. The new frame retained a similar geometry to 1991 with a half-degree increase in rake and a slightly lowered radiator placement standing out as the only significant changes. While similar in dimensions, the new frame featured stronger tubing, increased gusseting throughout, and a larger-diameter pivot bolt for the swingarm. Disappointingly, the new frame continued to lack a fully removable rear subframe, a feature that Honda and KTM had been offering on their full-size machines for nearly a decade at this point. While not critical to performance, this omission seemed rather egregious in an all-new design.

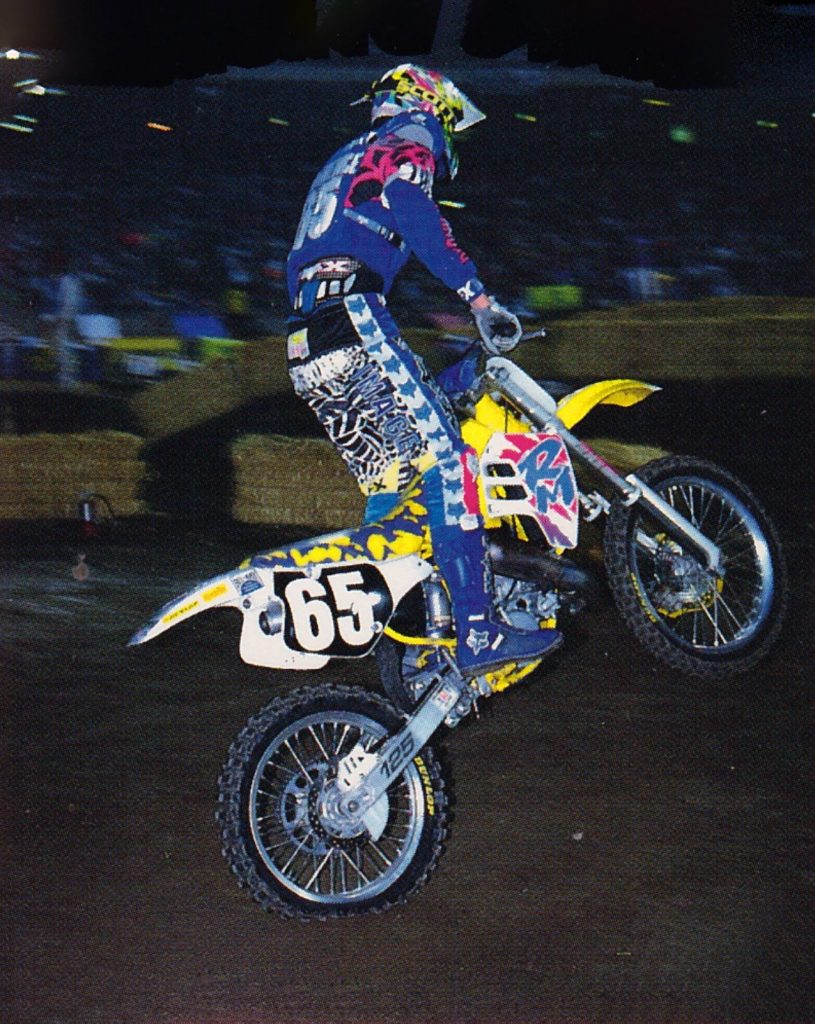

One of the big moves of the 1992 season was 1991 125 East Coast Supercross champion Brian Swink taking his number one plate from Honda to Suzuki. Brian would back up his ’91 title with another in 1992, also becoming the only rider to best West Coast champion Jeremy Mcgrath during the season. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

One of the big moves of the 1992 season was 1991 125 East Coast Supercross champion Brian Swink taking his number one plate from Honda to Suzuki. Brian would back up his ’91 title with another in 1992, also becoming the only rider to best West Coast champion Jeremy Mcgrath during the season. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the suspension front the RM125 was once again significantly updated for 1992. In 1991, Suzuki had switched from long-time partner Kayaba to Showa and had delivered surprisingly good results. After three years of grim Showa performance on the CRs, this was seen as a risky move, but Suzuki’s engineers turned out to have a much better handle on the Showa components. Both ends outperformed the Hondas by a wide margin any fears of grim fork performance were laid to rest.

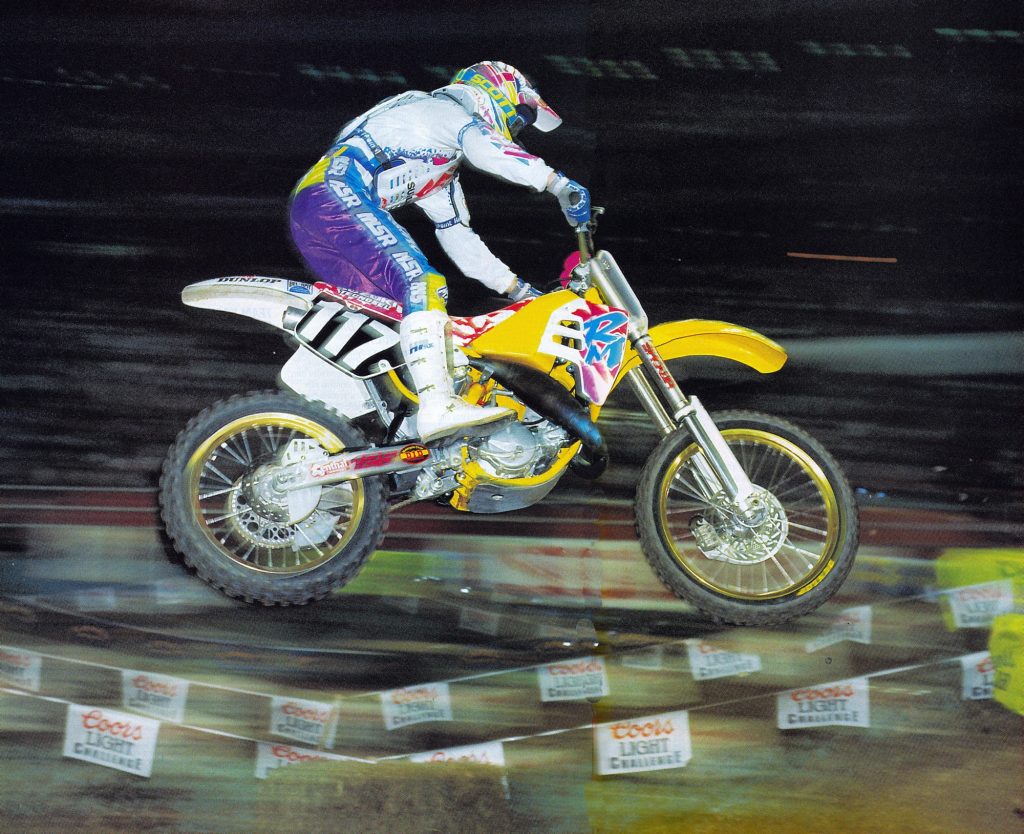

Fox Racing’s “Factory” Phil Lawrence took the all-new RM125 to fourth overall in the 1992 125 West Coast Supercross standings. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Fox Racing’s “Factory” Phil Lawrence took the all-new RM125 to fourth overall in the 1992 125 West Coast Supercross standings. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

For 1992, Suzuki once again stayed with Showa as the suspension provider on their RM125. Up front, the RM retained the inverted cartridge design of 1991 but added 1mm larger tubes, a one-piece fork seal collar, improved oil seals, all-new valving, and redesigned lower guards. Unlike the Showa fork found on the CR125R, the Suzuki version featured adjustments for both compression and rebound damping. Overall travel remained the same as 1991 with 12.2” of movement available.

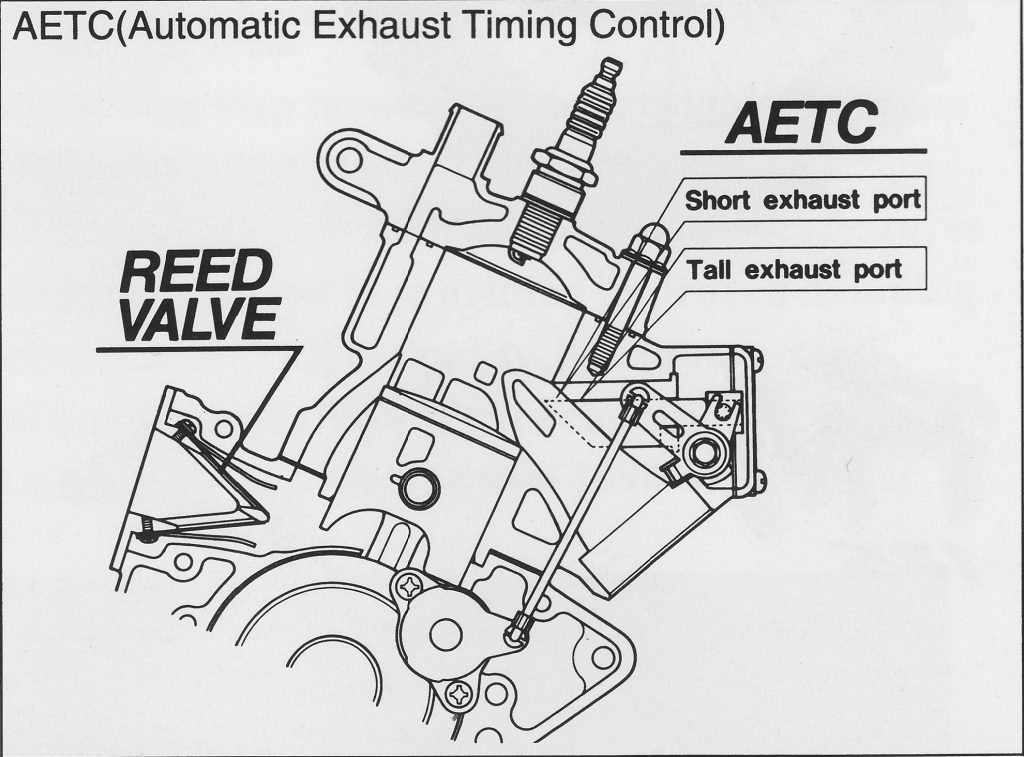

The 1992 Suzuki RM125 continued to use the same basic AETC variable exhaust valve system the yellow team had employed since 1987. Similar in theory to Honda’s HPP and Yamaha’s YVPS, the AETC employed a pair of sliding guillotine valves to vary the height of the exhaust port to optimize power. Photo Credit Suzuki

The 1992 Suzuki RM125 continued to use the same basic AETC variable exhaust valve system the yellow team had employed since 1987. Similar in theory to Honda’s HPP and Yamaha’s YVPS, the AETC employed a pair of sliding guillotine valves to vary the height of the exhaust port to optimize power. Photo Credit Suzuki

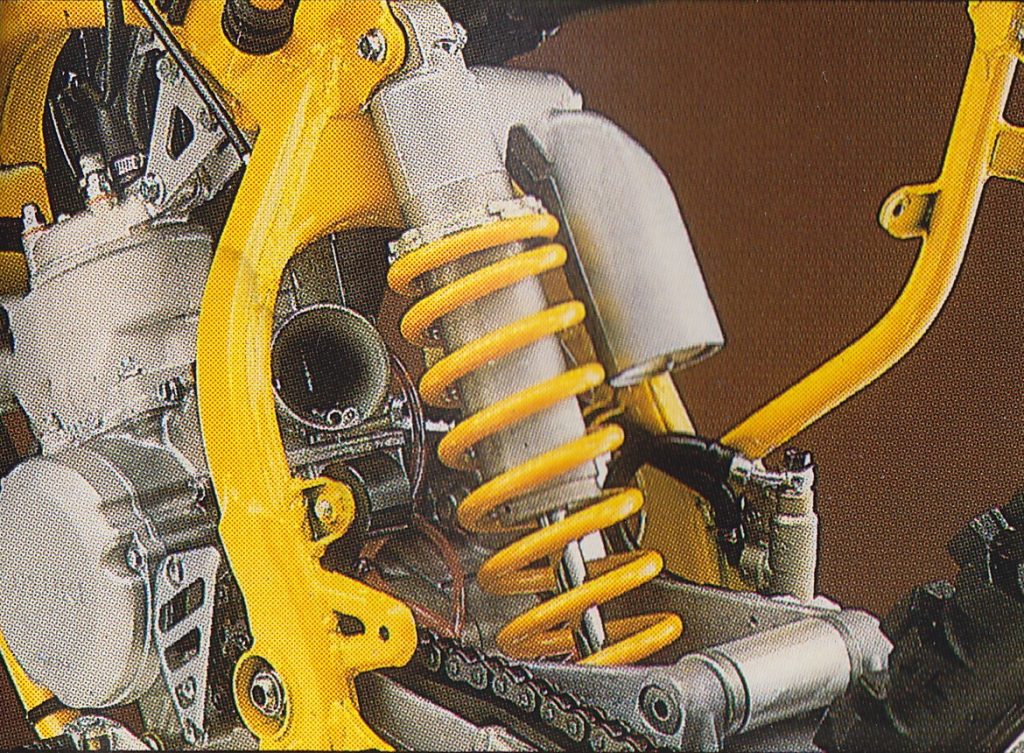

In the rear, the RM featured an all-new Showa shock that delivered 12.8” of rear wheel travel. The new damper was similar in design to 1991 but featured a larger piston and cylinder for improved oil flow and control. As in 1991, the damper offered a full range of adjustments for compression and rebound damping. Paired with the new shock was a redesigned swingarm and linkage which featured enlarged pivot points and upgraded bearings for improved action and increased durability. The rear wheel was strengthened as well with larger-diameter spokes and an additional bearing on the sprocket side. Both brakes also got an upgrade in 1992, with all-new rotors that were thicker to prevent bending and a redesigned front caliper that was less prone to flexing.

At first glance, the RM125 did not appear to be much different than the 1991 design. To those in the know, however, the biggest visual clue was the all-new tank and seat design which cleaned up the looks and made sliding forward in the turns easier. Photo Credit: Suzuki

At first glance, the RM125 did not appear to be much different than the 1991 design. To those in the know, however, the biggest visual clue was the all-new tank and seat design which cleaned up the looks and made sliding forward in the turns easier. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Lastly, an all-new tank and seat smoothed out the rider compartment and made sliding forward for turns easier. The new tank was slightly lower for 1992 and offered a cleaner appearance that was closer to the one found on the RM250. The new tank and lowered radiators also helped centralize mass for improved handling. In addition to the new plastic, the 1992 RM received an extremely bold update in graphics that set it apart from any other machine on the track. Even in 1992, this was a “love-it-or-hate-it” change and not many people fell in the middle.

In 1992, no other bike was as light, feathery, and flickable as Suzuki’s RM125. If you could not jump on this bike, it might be time to take up golf. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1992, no other bike was as light, feathery, and flickable as Suzuki’s RM125. If you could not jump on this bike, it might be time to take up golf. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the motor changes for 1992 did not result in a remarkably different power profile, the RM engine remained one of the most loved in the class. It was quick off the line, punchy in the middle and passible on top. This made the RM a great choice for riders without the skill to keep the Honda’s high-strung powerband at full boil. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While the motor changes for 1992 did not result in a remarkably different power profile, the RM engine remained one of the most loved in the class. It was quick off the line, punchy in the middle and passible on top. This made the RM a great choice for riders without the skill to keep the Honda’s high-strung powerband at full boil. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the track, the all-new RM125 turned out to be an improved version of the bike so many riders had embraced in 1991. The powerband remained focused in the midrange, with a quick spool-up and lightning-fast response. The added crank inertia for ‘92 allowed the RM to hook up better out of turns and the stronger midrange hit boosted the RM up and over obstacles with ease. Top end power was only average, and the RM began asking for a shift at about the time the CR was just getting started. If you tried to pin it to the stops and scream it like Guy Cooper, the RM would play along, but its most effective power was found lower down on the power curve. The intake changes cured the old model’s annoying bog, and the new motor was quick, snappy, easy-to-ride, and very competitive. The CR125R remained faster on top but it was far more difficult to keep on the pipe than the always-eager RM. When you added in the RM’s slick-shifting six-speed transmission and feather-light clutch, you had one of the best overall power packages in the class. Fast guys still loved the endless pull of the Honda, but for most riders the RM was a far better dance partner in 1992.

Coming into the 1992 125 season Guy Cooper (5) was still considered by many to be Suzuki’s best shot at a title. Unfortunately, an up-and down season would see the 1990 125 champ finish a disappointing seventh in the final standings. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Coming into the 1992 125 season Guy Cooper (5) was still considered by many to be Suzuki’s best shot at a title. Unfortunately, an up-and down season would see the 1990 125 champ finish a disappointing seventh in the final standings. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the chassis front, the RM was once again an upgraded version of what people had come to love about Suzuki’s 125s. The stronger forks and stiffer frame helped make the RM an absolute scalpel on the track. It could cut underneath any other machine on the track and that is in a class full of bikes that know how to turn. The Honda came closest in 1992 to matching its turning acumen but even the red machine could not match its effortless steering feel. On the RM, all you had to do was think about where you wanted to go, and the lithe chassis and snappy power did the rest. Jumping the RM was likewise a joy and the bike was easily the best machine for making that tricky double right out of a turn.

A beefed-up linkage and all-new shock promised improved suspension performance for 1992. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A beefed-up linkage and all-new shock promised improved suspension performance for 1992. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In terms of stability, the new chassis was slightly improved for 1992 but the RM remained far better at cornering than going straight. That same light feel and aggressive geometry that made the RM a joy in the turns could make it seem quite disconcerting at speed. Unlike the CR, which shook its head under deceleration, the RM tended to shake its head under power and generally wander about the track. At speed, the bike never really took a set and tended to dance around under the rider. Compared to the KX125, which was undeterred by nearly anything, the RM was a live wire of activity. Every rut, rock, and undulation in the terrain caused the Suzuki to react and the bike demanded constant attention once the speeds increased. In truth, the bike rarely did anything spooky, but that “I might just decide to spit you off” feeling at speed never quite went away.

The RMs new 46mm Showa forks delivered one of the best rides in the class in ’92.

The RMs new 46mm Showa forks delivered one of the best rides in the class in ’92.

Well sprung and expertly damped, they were not as ultra-plush as the Kayaba units found on the KX, but for many riders their slightly firmer action was just as capable on the track. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the suspension front, the RM125 delivered the second-best ride in the 1992 125 class. In truth, no other brand was in the same league as Kawasaki and their magic carpet KYBs in ‘92, but at least Suzuki came closest to making it into the same ballpark. The new Showa forks performed at least 150% better than the poorly setup ones found on the Honda and proved more than raceable in stock condition. They were not quite as plush as the ultra-smooth KYBs found on the KX, but they were well damped and sprung perfectly for most riders in the RM’s target demo.

The redesigned Showa shock for 1992 delivered a smoother ride than the year before, but it remained less compliant than the damper found on Kawasaki’s all-new KX125. Both machines were excellent in stock trim, but the RM’s firm and well-controlled ride required aggression to work its best. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The redesigned Showa shock for 1992 delivered a smoother ride than the year before, but it remained less compliant than the damper found on Kawasaki’s all-new KX125. Both machines were excellent in stock trim, but the RM’s firm and well-controlled ride required aggression to work its best. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Out back, the story was very much the same with a well-sorted and well-liked rear damper. The choppiness riders had complained about the year before was gone and the shock generally performed its job without drama. Big whoops and small were both taken in stride and the RM could be launched skyward without fear of a tooth-rattling landing. Once again, it was not quite as supple as the KX’s rear end, but some fast guys preferred the RM’s firmness to the KX’s cush. Much like the forks, it was a matter of taste and neither machine could be faulted in their overall suspension performance.

In 1992, there were three very solid choices and one true also-ran in the 125 division. Honda dominated the horsepower race while Kawasaki held a stranglehold in the suspension categories. Suzuki split the difference with a great motor and solid suspension, while Yamaha brought up the rear with an outdated and underpowered motor that held back its otherwise competitive package. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1992, there were three very solid choices and one true also-ran in the 125 division. Honda dominated the horsepower race while Kawasaki held a stranglehold in the suspension categories. Suzuki split the difference with a great motor and solid suspension, while Yamaha brought up the rear with an outdated and underpowered motor that held back its otherwise competitive package. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the detailing front the RM was improved in some areas but still a step behind the competition in others. The new brakes were stronger overall and more fade resistant than in the past. The squealing in the rear that annoyed riders the year before was gone and both ends were less grabby than in ’91. They were not quite as “works bike” powerful as the units found on the Honda but they were easily better than anything else in the class. The clutch and transmission were both loved for their smooth action, but some riders complained of accidental shifts due to its light touch. The light pull of the clutch also reflected its relatively soft springs and hard chargers were likely to want sturdier springs to prevent the clutch from fading in long motos.

In 1992, Ezra Lusk was the rider many believed would be the “next big thing” to take the sport by storm. A second place in the series opener seemed to validate this belief, but an inconsistent season overall left the Bainbridge, GA rider in fifth in the final standings. Two years later in 1994, Lusk would finally bring Suzuki a 125 East Coast Supercross championship.

In 1992, Ezra Lusk was the rider many believed would be the “next big thing” to take the sport by storm. A second place in the series opener seemed to validate this belief, but an inconsistent season overall left the Bainbridge, GA rider in fifth in the final standings. Two years later in 1994, Lusk would finally bring Suzuki a 125 East Coast Supercross championship.

While the bike’s graphics were polarizing, most riders liked the shape and feel of the RM’s bodywork. Taller riders preferred the roomy KX, but most average-sized pilots found the RM quite comfortable. The new seat and tank made moving around a breeze and everything fell easily to hand and foot. The bars, levers, grips, and perches were not the class of the field, but most riders could live with them until something was bent or broken. Removing that vulcanized throttle grip, however, was a process invented by the Marquis De Sade.

Running your number on top of the garish stock graphics was definitely not the hot setup in 1992. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

Running your number on top of the garish stock graphics was definitely not the hot setup in 1992. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

Speaking of annoyances, the need to remove the stock decals before racing the bike might have seemed minor, but I’m sure more than a few scorers found themselves cursing Suzuki once proud RM owners got the bright idea to just slap numbers on over the zebra stripes. This was more common than you might think and there are probably a few ratty ’92 RMs still running around Craigslist with some version of these side panel stripes still intact. In truth, aside from the oddball graphics, the 1992 RM was not a bad looking motorcycle. If you ditched the zebra stripes and Moon Base Alpha seat cover and went with a solid yellow seat and rear fender (as the Factory Suzuki team did later in the year) the machine could be quite handsome.

Over-the-top in appearance but excellent on the track, the 1992 Suzuki RM125 was the rare case where marketing extravagance was backed up with truly great execution. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Over-the-top in appearance but excellent on the track, the 1992 Suzuki RM125 was the rare case where marketing extravagance was backed up with truly great execution. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Today, the 1992 Suzuki RM125 is an icon of early 90s moto culture. A machine so outlandish in appearance that it is revered today even by riders who hated its looks at the time. Thirty years on its styling has overshadowed most of its other attributes, but the RM was far more than an interesting styling exercise. Underneath its unusual appearance beat the heart of a winner. Snappy, fun, and deceptively fast, the 1992 RM was a lethal motocross weapon wrapped in a Rainbow Sparkle attire.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com