For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at what many consider the last truly great Honda 250 two-stroke, the 1996 CR250R.

Today, the 1996 Honda CR250R remains one of the most iconic machines in motocross history. Ridden to Supercross glory by Jeremy McGrath, this steel-framed beauty was the last of its breed and the end of an era. Photo Credit: Honda

Today, the 1996 Honda CR250R remains one of the most iconic machines in motocross history. Ridden to Supercross glory by Jeremy McGrath, this steel-framed beauty was the last of its breed and the end of an era. Photo Credit: Honda

Few machines in motocross have as storied a history as Honda’s CR250. In 1973, it became the first truly competitive motocrosser from Japan. In 1981, it took Team USA to America’s first Trophy des Nations victory. From 1982 thru 1996, Red Riders were victorious in nine of fifteen 250 National Motocross championships and thirteen of fifteen Supercross title chases run. During this era of Honda domination, their riders would win an unprecedented nine straight Supercross titles from ’88 thru ’96. Hansen, Bailey, O’Mara, Johnson, Stanton, and McGrath all took turns aboard the red rockets, and all brought home Supercross and National Motocross titles. In 1996, the Honda CR250R was on top of the motocross world.

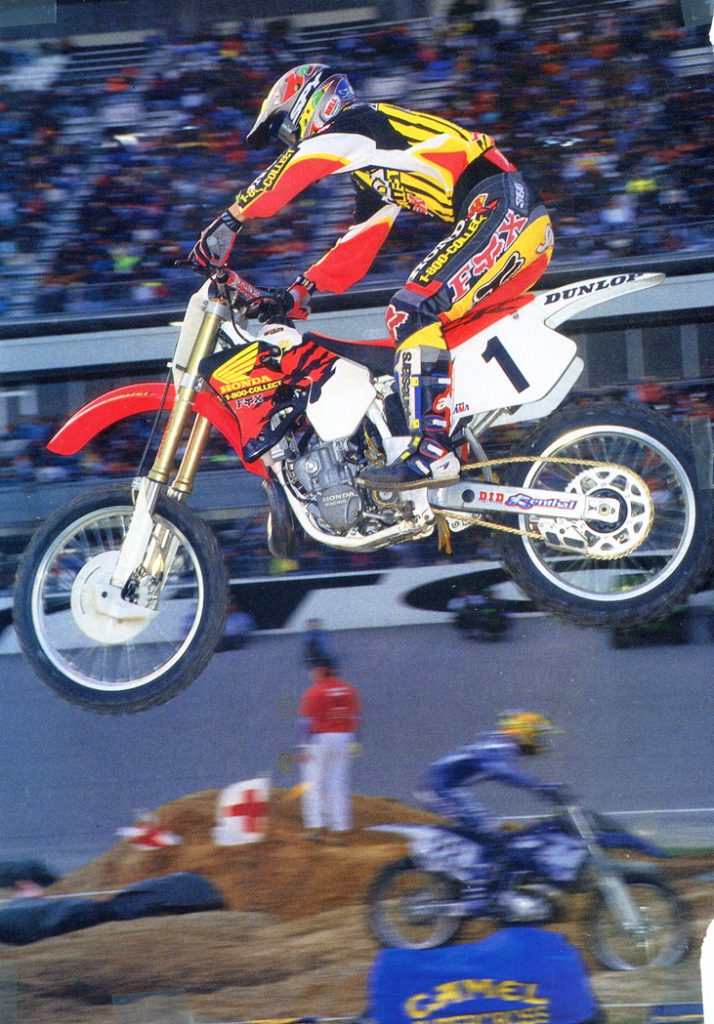

The King: To say Jeremy McGrath was on fire in ’96 on his Factory Honda CR250R would have to be a massive understatement. MC would win every race save one (St. Louis), roosting away to his fourth consecutive Supercross title in the process. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The King: To say Jeremy McGrath was on fire in ’96 on his Factory Honda CR250R would have to be a massive understatement. MC would win every race save one (St. Louis), roosting away to his fourth consecutive Supercross title in the process. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

This golden age of Honda 250 domination had truly started in the fall of 1982, with the introduction of Honda’s revolutionary ’83 CR lineup. After the success of the original ’73 CR250M Elsinore, Honda had spent the rest of the decade playing catchup to its Japanese competitors. The introduction of the groundbreaking Yamaha YZ250 and revolutionary Suzuki RM250 quickly relegated the Elsie to yesterday’s news in the mind of consumers. Then in 1980, the fortunes of the CR250R would forever be changed by the arrival of Suzuki’s five-time World Motocross champion Roger De Coster to Team Honda. De Coster was looking to race one more year in the GP’s, before moving to a role in-house as a manager and consultant. After spending the ’80 season racing a Honda RC500 on the GP’s circuit, The Man turned his immense knowledge, skill and engineering know-how toward turning around the Honda’s ailing production bike program.

Mega-motor: In 1996, this was the ultimate motocross engine. Brutally fast, slick-shifting and claw-hammer reliable, 250 two-strokes didn’t get any better than this. Photo Credit: Honda

After a run of decent, if not spectacular CR’s in the late seventies, Honda hit the skids in 1981. The all-new space-age ‘81 CR250R was trick, but basically a laughing stock in every other way. Overweight, underpowered and unreliable, it was a machine nearly without virtue. In 1982, the first of the true “De Coster” CR’s would debut to much fanfare. After the abysmal ’81 models, the much-improved 1982s turned out to be a true revelation and put Honda back on the map and into contention. Then in 1983, Honda would introduce the bikes that would kick off a decade of domination. The ’83 CRs were styled after their incredibly trick RC works bikes and easily the best bikes Honda had produced since the original 1973 Elsinore. The ’83 CRs looked great, performed well and converted countless riders away from yellow to red.

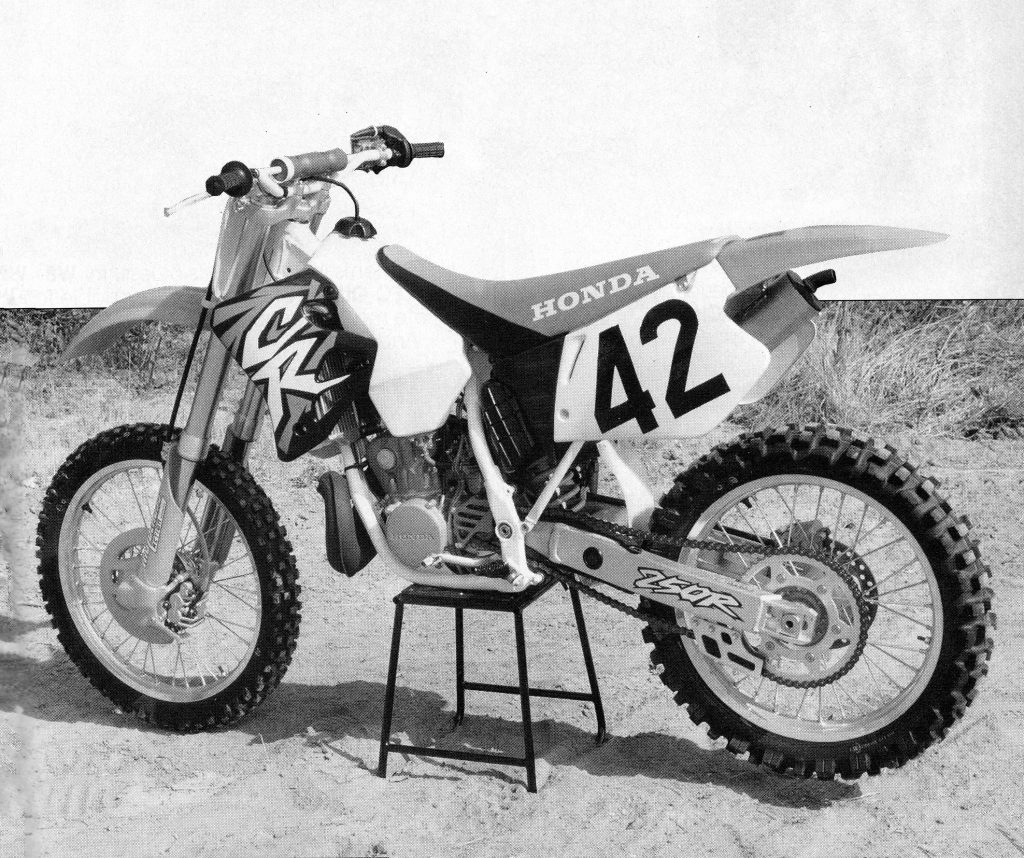

While not exactly beautiful (I was not a fan of the side plates on the ’95-’96 model CRs), the stock 1996 Hondas were certainly more understated than the crazy purple ’95s had been. Photo Credit: Honda

For the next decade, the Honda CR250R would be without a doubt, the most successful machine in motocross. It was not always the best bike in all categories (most notably suspension), but it was consistently the fastest, best built and best handling. In ’86, Honda would introduce their omnipotent HPP motor and Showa cartridge fork, then in ’88, they would push the styling and ergonomic envelope with their works-inspired low-boy layout and sexy blood-red color scheme. A switch back to the early eighties Flash Red color and the addition of a set of tiger stripes to the seat would ring in the nineties with a bang, as the mighty CR continued its winning ways.

Jack-of-all-trades: Lug it, clutch it, scream it till the cows come home; it didn’t matter, the CR was ready to do battle no matter your preference. Blessed with perfectly positioned power and the ability to do in one shift what others did in two (or even three), the CR’s power plant had all the bases covered in 1996. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Jack-of-all-trades: Lug it, clutch it, scream it till the cows come home; it didn’t matter, the CR was ready to do battle no matter your preference. Blessed with perfectly positioned power and the ability to do in one shift what others did in two (or even three), the CR’s power plant had all the bases covered in 1996. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The 1992 season would see the introduction of the most radically redesigned CR250R in a decade. The ’92 CR featured the first all-new motor since 1986 and a completely redesigned chassis. The new bike was lighter, slimmer and more Supercross-focused than ever before. All-new bodywork graced the machine that did away with the Flash Red color of ’91. In its place, Honda bolted on a set of new fluorescent pink plastics they coined “Nuclear Red.” The new color was certainly bolder, but not everyone loved the new look.

While there had been better turning CR250’s (most notably, 1993), the 1996 was no slouch in the twisties. It was still plenty sharp in the corners and did a good job of walking the tightrope between twitchy and terrifying. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the ’92 model suffered some growing pains (lack of low-end, chassis flex and frame breakage), the CR continued to be the mount of choice for pros and hard-charging intermediates. For ’93, Honda beefed up the frame and pumped up the horsepower, resulting in one of the best CR250R’s ever built. It still had crummy suspension, but oh could it handle. Nothing could turn under the scalpel-like CR as it roosted away to a sixth straight Supercross title. The ’94 and ’95 season would see minor modifications to the basic ’92 platform. A change in geometry would attempt to tame the bike’s nasty headshake (at the cost of some of that legendary turning) and a switch to Kayaba components would try to alleviate its grim suspension reputation. Even with these mods, however, the basic Honda CR250R formula persisted – a harsh ride, combined with razor-sharp steering and a rocket motor. With the ’96 season approaching and a radically redesigned CR250R on the horizon, Honda prepared to enjoy one last go around with the Grand Dame of Supercross.

Holeshot machine: McGrath used Honda power to good effect in 1996. Photo Credit: RacerX

Knowing full well that this was going to be the last year of a very proven design, Honda only made minor changes to their award-winning package for ’96. First on the list (and probably most appreciated by many), was a switch from the purple of the ’95 CR to the much more tasteful red and black of the Factory bikes. In addition to the new duds, a 46mm USD Kayaba cartridge fork was pilfered off the KX250 in an attempt to once again fix the CR’s suspension woes. Rounding out the changes for ’96 were a slightly narrower exhaust port (44.4mm vs. 43.7mm), a new ignition, a larger carb bore (.3mm larger) and one more tooth for the rear sprocket.

Supercross bred: If catching air was your bag, the 1996 CR250R was a willing partner. Mark Easley demonstrates. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

In terms of performance, there was a very good reason Honda left their motor basically alone for ’96. Starting with the original HPP mill in 1986, few bikes had been able to run with Honda’s 250cc MX missile. It was the gold standard of the 250 class, and by 1996, had racked up a full decade of motor dominance. Put frankly, nothing was as fast, broad or brutally effective as Honda’s CR250R.

While Steve Lamson was certainly better known for his outdoor prowess, he did have a few good rides indoors on the ’96 CR. A pair of thirds at Anaheim and Seattle had the Honda team smiling, but an injury would knock Steve out of the series by the half way mark. Lamson would rebound in the outdoors and dominate his way to a second consecutive 125 motocross title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the CR was universally acknowledged as having the best power plant in the class, it was not without fault. When Honda had introduced their new 250 mill in 1992, the one area it lagged behind its predecessor was in low-end response. While this had gotten slightly better with the ‘93-’95 mill, the CR still lacked the hard-hitting explosion off the line familiar to fans of the KX250. The CR was solid and torquey, but not awe-inspiring below 5000 rpm. With the addition of a new digital ignition, revised porting and lower gearing, Honda hoped to punch up the low-end response for ‘96.

While the ’95 Factory bike differed drastically from the looks of the stock CR, the ’96 version played it closer to the vest. Although Jeremy and Steve’s bikes looked identical, MC preferred to run the more aggressive 1993 CR250R frame over the more sedate ’96 chassis. Photo Credit: Bill Amick

While still not a tractor down low, the 1996 CR offered the best grunt of any Honda 250 since 1991. It barked to attention off the line, and then pulled smoothly into an endless rush of power. While the midrange hit was prodigious, it seemed lees abrupt than previous CRs due to the beefed up low-end. Past the midrange, the CR just kept pulling like a freight train well past the point where the other 250s had thrown in the towel. In ’96, this was the ultimate motocross powerband.

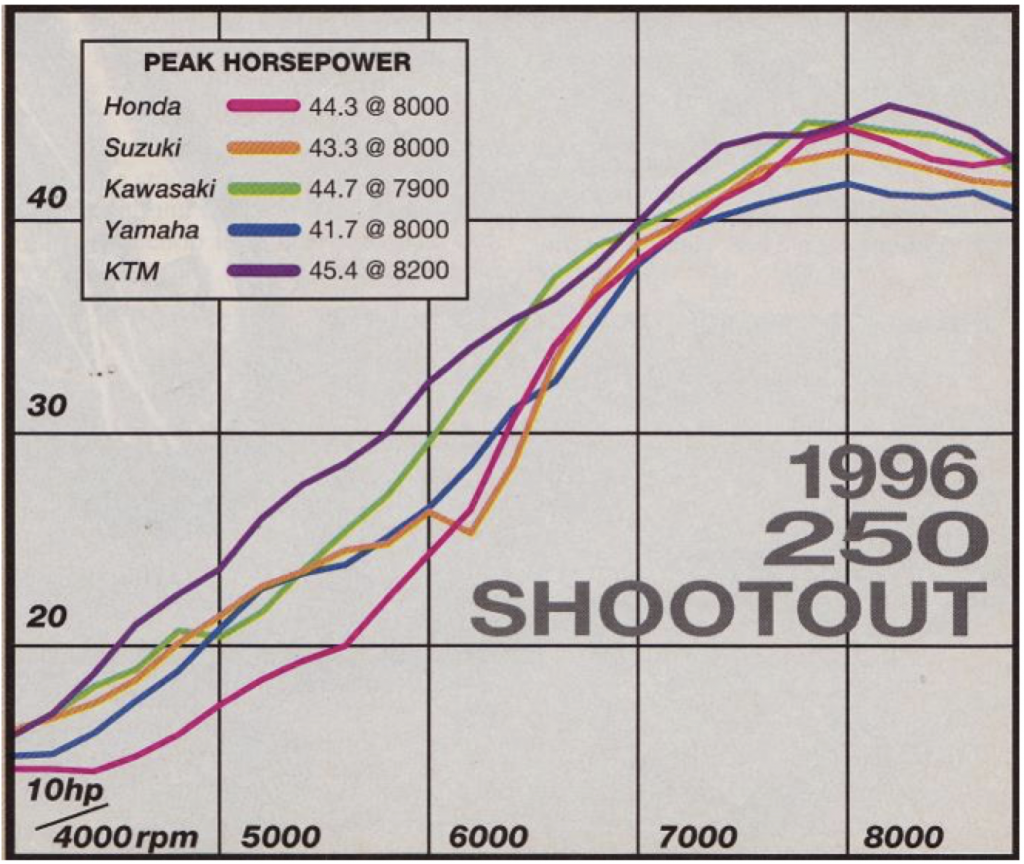

On the dyno, the CR250R looked less impressive than its real world performance would suggest. Both the KTM and Kawasaki posted better peak numbers and beat the Honda at nearly every point on the curve. On the track, however, the Honda’s perfectly positioned power, snappy delivery and endless rev gave it an advantage no machine could top. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Behind the CR, we had two very good mills, an enduro bike and a colossal disappointment. First up, was the KX250, which could have unseated the Honda with a little more rev. For 1996, Kawasaki produced an absolute rocket, which barked off the line and ripped through the middle. After this prodigious hit, the power fell off suddenly and demanded another gear to keep the fun going. While the KX was certainly plenty fast, it lacked the long pull of the Honda and required twice the shifts per lap of the red machine.

After four straight titles and countless victories, Jeremy McGrath would shock the industry by parting ways with Team Honda at the end of the season. Jeremy’s reported dislike for the new alloy-framed ’97 CR250R was pointed to as a major factor in his decision to leave. Photo Credit: Honda

In third, we had the all-new RM250, and its mellower take on Honda style power. For ’96, Suzuki had tried to clone the omnipotent CR’s powerband and got it about 80% right. Both bikes ran very similarly on the track, with a punchy midrange and wide power spread. Where the RM went wrong, however, was in the amount of that power. It was snappy and easy to ride, but slower than both the CR and KX.

Pros like Ronnie Lechien could make the CR250R fly in 1996. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Ironically, it was the bike that dominated the horsepower rankings that finished near the back of the pack in the real world standings. On the Dyno, the KTM bested all comers by a wide margin at nearly every point on the curve. Its power graph towered over the others and looked unbeatable. In the real world, however, the Katoom lacked the snap of the others. Its powerband was broad and easy to ride, but slow to build and lethargic. It had a heavy flywheeled enduro feel, which was better suited to off-road than motocross.

The addition of a high-speed compression adjuster on the ’96 CR shocks was a case of Factory trickery being trickled down to the common man. Whether or not 90% of the CR’s riders could actually decipher its function was another matter. Photo Credit: Honda

In last place, we had the new-look YZ, which was unfortunately saddled with a very old-look YZ powerband. The new Y-Zed made huge strides in handling, ergonomics and styling, but took just a big step backwards in motor department. For ’96, the YZ produced a very narrow spread of power-situated dead center in the midrange. Above or below this hit, there was very little thrust available. On the dyno, it made two horsepower less than the mellow Suzuki and three to four horsepower less than the Kawasaki, Honda and KTM. Unless you were going to race the novice class, motor work was on the menu for YZ pilots in ’96.

The 1996 CR250R was a serious race bike, made for serious riders. If you were a novice, its suspension was likely to beat you to death, but if you were fond of mega leaps, the CR was the right bike for the job. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The fact that Honda once again claimed the motor victory was certainly no shock. By 1996, their motor dominance had become all but a forgone conclusion. For Honda owners the true concern was never the engine, it was the suspension.

Pilfered: For 1996, Honda did more than try and copy the well-regarded forks from the KX250, they stole them right off the bike. The 46mm KYB cartridge forks were the exact same units found on the ’96 Kawasaki and hopefully spelled an end to Honda’s front suspension woes. Unfortunately, the KYB units were still set up by Honda and just as poor-performing as the year before. Overly stiff for anything but Supercross, they were harsh in the mid-stroke and unforgiving on small impacts. Photo Credit: Honda

By 1996, the CR250 had been in production for a full twenty-three years and in all that time, the mighty Red Rooster had claimed the suspension title of the 250 class a grand total of two times. Other than the glory years of ’86 and ’87, the Honda suspension story was a twisted tail of bruised buttocks and battered wrists. It did not seem to matter who made the components, or how they were manufactured, if they were bolted to a CR250R, they were bound to be bad.

Bulletproof: In 1996, this was the best clutch and gearbox combo in motocross. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1995, Honda had tried to improve their lot by switching from Showa to Kayaba as their suspension supplier. At the time, the KYB’s on the Kawasaki was considered the best forks in motocross and the switch seemed to make a lot of sense. In practice, however, the results turned out to be no better than the year before (or the year before that, or the year before that…). The new Kayabas were just as badly set up as the Showas had been, thus continuing Honda’s eight-year run of crummy forks.

After shutting up his critics in 1995 with the 250 National Motocross title, Jeremy was once more on fire in ’96. By winning five of the first six races, the reigning champ looked to be on his way to back-to-back 250 titles. After dominating the first half of the series, a crash at Milville and an early retirement at Washougal would open the door for Jeff Emig to challenge for the title. In the end, the series would come down to the last round, where Emig would go 1-1 to Jeremy’s 2-3 and claim his first 250 Motocross title. Photo Credit: Paul Buckley

For 1996, Honda stayed the course and kept Kayaba as the suspension supplier, but took no chances by pilfered the exact fork Kawasaki was using on their well-regarded KX250. Once again, however, Honda’s engineers found a way to turn a silk purse into a sow’s ear. As delivered on the CR250R, this previously plush 46mm KYB fork offered a harsh and jarring ride on anything short of a Supercross track. The stock springs and damping were too stiff for most mortals and pummeled your hands and wrists on breaking bumps and small hits. On big jumps and hard G-outs, they performed well but were brutal on the kind of sharp, small bumps that make up most motocross courses. For most riders, a drop in oil height from 92mm to 115mm could take out enough of the harshness to make them livable, but they were never going to be in the same league as the ultra-plush 49mm Twin-Chamber conventional Showa’s found on the RM250.

Just like the forks, the CR’s rear KYB was too rigid for anything but Robbie Knievel style antics. A drop in spring rate helped, but plush was never going to be in the ’96 CR’s vocabulary. Photo Credit: Honda

Out back, the story was only slightly better for Honda aficionados. For 1996, Honda trickled down a bit of their works technology to the 250 class with the introduction of a new Kayaba shock that featured both high and low-speed compression adjustability. This was a feature that had been found on Factory bikes for several years and offered a new level of suspension fine-tuning (and complexity). This new damping adjustment retained the traditional slotted screw adjustment for low-speed compression and added a large outer knob for high-speed compression adjustment. Rebound adjustment was still handled by the traditional rebound screw on the lower portion of the shock.

Successes on the 1996 CR250R were not just limited to the AMA schedule. Across the pond, Belgium’s Stefan Everts (sandwiched here between fellow Honda riders Joakim Karlsson and Alex Puzar) piloted his CR250R to his second of three 250 World Motocross titles in 1996. Photo Credit: Motocross Journal

While certainly trick, the new shock actually performed no better than the simpler unit it replaced. Like the forks, it was set up very stiff and only worked well on huge jumps and hard landings. Small chop and braking bumps were transmitted straight to the rider’s backside and the new adjuster probably confused more riders than it helped. In stock condition, the rear was oversprung and underdamped, with a harsh and kidney-busting ride. A drop down from a 5.6 spring to a 5.4 helped matters and brought the shock down from buckboard stiff to mildly jarring, Is stock condition, it was never going to be plush, but it could be raced (just remember to bring your kidney belt). For Supercross, it worked very well, but for outdoor motocross, there were better choices available.

A slim rider compartment, quality controls and a comfy and durable seat all made the CR250 a pleasant place to do business in 1996. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the handling department, the CR remained the same sharp and twitchy machine it had been since 1983. In the corners the CR was a joy, with excellent steering manners and a planted feel. The Honda went where you pointed it and was happy to carve any arc you were brave enough to attempt. The ’96 version of CR handling was not quite as razor sharp and accurate at the original ’93 version, but the new bike was also less prone to violent headshake at speed than its predecessor. Aerial manners were excellent and the CR was confidence inspiring no matter the conditions.

After a decade of braking dominance, Honda finally started to feel a little pressure in 1996. Still as reliable and trouble free as ever, they were good, but not as outright powerful as the new RM and YZ’s binders. Photo Credit: Honda

In the detailing department, the CR250R remained the best-built and most reliable bike by a wide margin. Nothing unexpected broke or fell off, the footpegs didn’t droop and the seat foam did not sack out. Plastic quality, bolt selection and ease of maintenance all remained the best in the class. In a few other areas though, the competition was quickly catching up.

In the halcyon days before cell phones were on every hip, people actually had to use pay phones and collect calling was big business. 1-800-COLLECT became a major sponsor of Team Honda in 1994 and remained with them until Jeremy McGrath’s defection to Suzuki of Troy in 1997. Photo Credit: Stephane LeGrand

Brake quality was still very good, but no longer the head of the class. For the first time in over a decade, Honda actually lost the braking category to another manufacturer. In 1996, it was Yamaha and their new Akebono components that sat atop the binder standings. Both in terms of clutch feel and durability, the CR remained excellent, but its old-school high-effort pull was the hardest in the 250 class.

The 1996 CR250R is considered by many to be the last of the truly great Honda two-stroke 250s. The arrival of the alloy framed ’97 CR would signal the end of a dynasty reaching all the way back to 1983. They were not always the best at everything, but they were the best at the things that counted to hard-core racers. Nothing was faster, nimbler or better built than a CR250R. If you were good enough for it, it was good enough for you. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1996, Honda built the ultimate Supercross weapon. The CR was rocket-fast, turned on a dime and able to leap tall buildings in a single bound. For less superhuman heroics, it was a bit unforgiving, but if you were fast enough to make its suspension work, it was hard to go wrong riding red. For more than a decade, the mighty Honda CR250R ruled supreme and the ’96 model was the last in that truly great blood line. After 1996, the CR250R would continue to be produced for another ten years, but it would never again reach the heights of its early nineties glory.