For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the machine that took Micky Dymond to a second consecutive 125 National Motocross title, the 1987 Honda CR125R.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the machine that took Micky Dymond to a second consecutive 125 National Motocross title, the 1987 Honda CR125R.

|

|

In 1986, the Honda CR125R dominated racing with a powerful motor, sano looks and razor-sharp handling. For 1987, the champ was back with an all-new motor, improved ergonomics and works-bike suspension. |

In 1986, Honda offered perhaps the most dominant line of motocross machines ever. The ’86 CR’s were top of the class in every division from 80 to 500 and swept all four National Motocross and Supercross titles. They offered the most power, the best suspension and the cashet of the winningest team in motocross. In 1986, if you were not on a Honda, you were racing for second place.

|

|

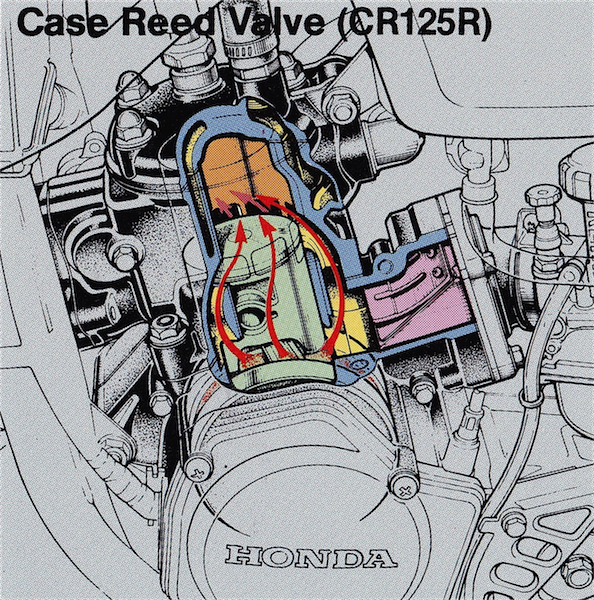

Deep Breather: For 1987, Honda ditched the motor that had dominated racing in 1986 and spec’d out an all-new case-reed mill. The new case-reed design offered more overall port area for better breathing and a more compact profile for better weight distribution. The CR125R would retain this intake configuration until its demise in 2007. |

For 1987, Honda took the bold move of completely redesigning their championship winning eighth-liter machine. In 1986, the CR125R had been universally loved for its torquey power and meaty delivery. The little CR barked off idle (for a 125) and pulled with authority over a broad range. It was by far the best 125 motor of ’86 and a bit of a vindication for Honda’s controversial ATAC system.

|

|

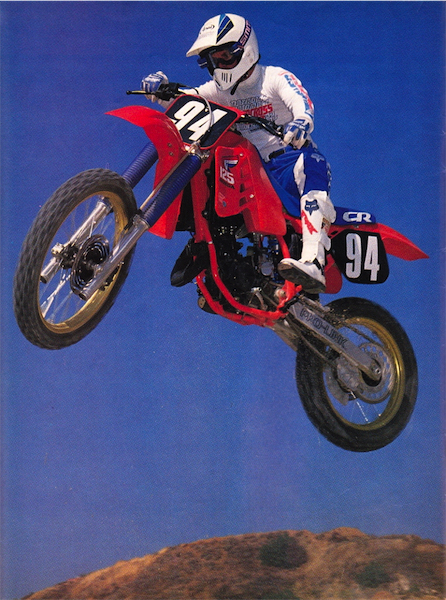

In 1987, nothing was as hard hitting, high jumping or hot handling as the Honda CR125R. Reigning 250 National and Supercross champion Ricky Johnson demonstrates. |

|

|

For 1987, a new slimmer low-boy tank, up-the-tank saddle and streamlined side panels improved ergonomics and gave the CR a new look. |

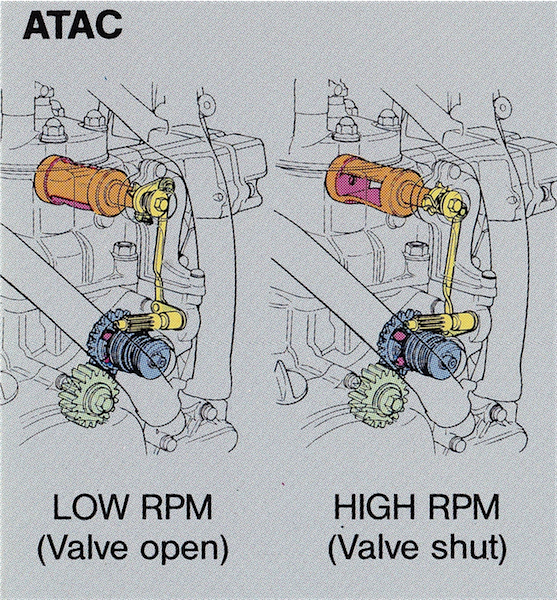

The original ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) had been introduced in 1984 as an answer to Yamaha’s revolutionary YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) variable exhaust port system. The YPVS was the first “power valve” to find its way onto a production machine and made its debut on the 1982 YZ125 and YZ250. In the case of the YPVS, a rotating drum was used to cover or uncover the top of the exhaust port based on engine rpm. By altering the port timing to better match engine rpm, Yamaha’s engineers could (in theory) provide a wider powerband.

|

|

The new 124.8cc case-reed mill on the CR125R produced less torque than ’86, but substantially more top-end power. It combined the broad spread of the KX125, with the hard hit of the YZ and endless rev of the RM into an unbeatable motor package. |

In Honda’s case, they eschewed the Yamaha route and chose to add an external exhaust canister to the manifold to boost head pipe volume. The theory behind this design was to trick the motor into thinking you had a “torque pipe” and a “rev pipe” installed by opening and closing a small butterfly valve based on engine rpm. Below 6000 rpm, the valve was open, adding a small amount of exhaust pipe volume to boost low-end. Above the 6000 rpm mark, a small centrifugal governor closed the valve to improve flow and top-end pull. While the theory behind this seemed perfectly sound, in practice, it proved less effective.

|

|

In 1986, Micky Dymond had been picked out of the relative obscurity of Team Husqvarna to take Ronnie Lechien’s spot on the powerful Honda squad. Micky would reward Honda’s faith with the 1986 125 National Motocross title and come into the 1987 season has the heavy favorite to repeat on the all new CR. |

|

|

Cachet: In 1986 and 1987, rolling a Honda out of your trailer meant instant credibility. No bikes in motocross were as dominant as the red and blue CR’s. |

In 1984 and 1985, the ATAC equipped CR125R produced a pleasant and easy-to-ride powerband, but little in the way of serious forward thrust. It was a good novice motor, but no match for the rip-snorting Kawasaki KX125. The addition of the ATAC did little to boost power (and added greatly to maintenance with its propensity to clog with carbon buildup) over the excellent ’83 CR, and many riders actually disconnected it altogether. It was not until ’86 that Honda’s version of the exhaust gizmo finally started to show some promise.

|

|

For 1987, Honda completely redesigned the ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) system they had been using since 1984. They enlarged and repositioned the resonance chamber to be closer to the exhaust port and did away with the problematic butterfly valve in favor of a more precise rotating drum-valve. The result was better sealing, increased flow and much better performance. |

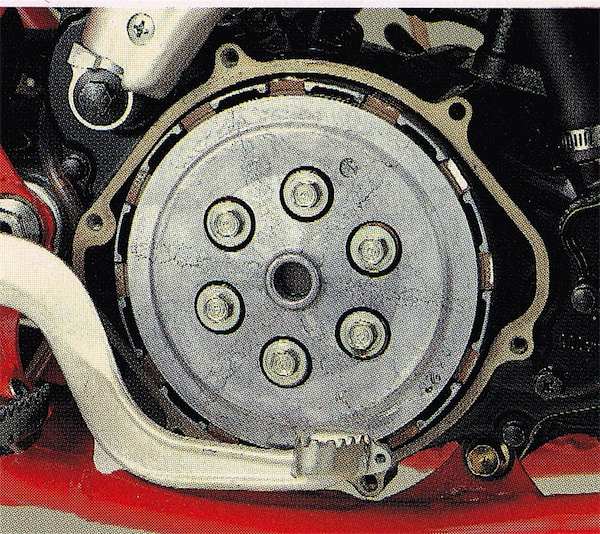

For 1987, Honda decided not to add the excellent, but extremely complicated HPP (Honda Port Port) system from their CR250R to the 125. Instead, the engineers chose to redesign the original ATAC system and graft it onto an all-new case-reed mill. Compared to ’86, the new engine offered slightly more displacement (124.8cc vs. 123.6cc) and more compression (8.8:1 VS. 8.4:1) through a slightly longer stroke. The switch to case-reed for ‘87 improved intake efficiency and increased the overall port area by 20% for better high-rpm flow. In the bottom end, a new crank with a one millimeter larger big-end bearing was spec’d to increase durability. Both the transmission and clutch were also improved with the addition of one tooth on all the gears for increased strength, and the inclusion of a quick access clutch cover for the first time.

|

|

Frequent Flyer: Sleek ergos, flawless manners and a rocket-fast motor all added up to major air time in 1987 for the Red Rooster. |

In the top end, the new ATAC retained the ’84-’85’s resonance chamber, but repositioned it to be closer to the exhaust port for better flow. Volume of the ATAC chamber itself was also increased by 45cc for better low-end torque. The troublesome butterfly valve of the old system was also scrapped, in favor of a rotating drum-valve that offered better sealing, easier maintenance and more precise action. Finishing off the motor package was an all-new pipe, revised ignition and 34mm flat-slide Keihin carb.

|

|

Works: The inclusion of a removable clutch cover on the new CR’s was big news for 1987. This little bit of works trickery passed down to the common man showed Honda’s commitment to producing the absolute best machines available at the time. |

On the track, the new case-reed CR was once again the power-monger of the 125 class. In 1986, the CR had offered a strong low-to-mid blast and a punchy delivery, but only moderate top-end pull. For ’87, Honda refocused that power higher up in the rpm range for a wider spread and more top-end power. Low-end was still generous for a 125 (although not as potent as the ’87 YZ or ’86 CR), but the real fun did not start until the midrange. Once the red tiddler wacked open the new ATAC valve and climbed on the pipe, it was all fire and brimstone till the CR finally called off the dogs at 12,000 rpm. From the midrange up, nothing could touch the mighty CR125R. It offered both the widest usable spread and strongest pull of any 125 in ’87. Topping off this incredible motor package was a bulletproof clutch and slick shifting six-speed trans that lapped the other 125s in both action and feel. In 1987, no other 125 was even close.

|

|

The Gold Standard: In 1986, Honda blew the wigs off the motocross establishment with the introduction of Showa’s new 43mm “cartridge” forks. Long the staple of Honda’s works machines, this high tech design offered a level of comfort and control never before seen on a production motocross machine. For 1987, Honda saw fit to trickle this technology down to the CR125R for the first time. Super plush and nearly flawless in their performance, they would stand as the high water mark for Honda fork performance well into the new millennium. |

While the motor was most certainly the star of the new ’87 CR, it was far from the bikes only virtue. For 1987, Honda had seen fit to finally equip their eighth-liter rocket with the latest in suspension components. Previously, the Honda 125’s had been a year or two behind the equipment offered on the 250 and 500. For ’87, that gap disappeared with an upgrade to Showa’s latest 43mm cartridge forks. These high-tech beauties had taken the sport by storm in 1986 and laid waste to the damper-rod competition. For 1987, only Honda and Suzuki (equipped with Kayaba’s new cartridge sliders) would receive the benefit of these works-caliber suspension components.

|

|

If you were riding something other than red in 1987, you were fighting for second place. |

|

|

In 1987, Larry Brooks was a hard charging privateer on the new Honda CR125R. At the ‘87 South Carolina 125 National Brooks was out front and pulling away to his first National win when the top-end bearing let go on his CR, ending his hopes for a victory. |

The benefit of the cartridge design was that it offered both a smoother action and a far wider range of damping adjustability than a traditional damper-rod system. With Suzuki and Honda being the only machines to offer this technology in ’87, there were really only two legitimate suspension players in the field. Both the Honda and Suzuki outclassed the undersprung Kawasaki and incredibly harsh YZ by a wide margin. In the final standings, the title of top fork of ’87 when to the Suzuki by virtue of its greater adjustability (it offered both compression and rebound adjustments to Honda’s compression only) and incredibly plush action. The Honda was a very close second and not a single tester complained about its smooth performance.

|

|

Hunchback: For 1987, Honda spec’d an all-new shock design for all the full-sice CR’s. This new “piggyback” design moved the shock reservoir from a tethered location on the frame to the top of the shock body itself. While this new design was lighter and more compact, the new location brought with it problems of its own. Because the reservoir was now buried deep inside the bodywork, it received very little cooling air and suffered from premature fade (the same problem that had troubled early Yamaha monoshocks). This design would only last one year on the 250 and be fazed out on the 125 and 500 by 1989. |

|

|

While Micky’s 1987 Factory Honda CR125R was a far cry from the exotic machine Ron Lechien had used to win the title in 1985; it was still considered the best machine in the 125 class. Of course, it did not hurt to start with (by far) the best bike as a jumping off point. |

In the rear, things were slightly less rosy for 1987. Even in its heyday, Honda was not known for rear suspension excellence and the new CR continued this trend. For 1987, Honda spec’d an all-new KYB “piggyback” shock (the 125, 250 and 500 all used this odd configuration, but the big bikes actually came equipped with a Showa version of the same design) that moved the remote reservoir from the frame to the top of the shock. While this was more compact and did away with the sometimes unreliable fluid line running between the shock and reservoir, the new position caused problems of its own. Because the canister now sat on top of the shock body, it was buried deep inside the body work between the seat and airbox. This positioning meant the shock reservoir received very little in the way of the cooling air. Without a steady flow of air to keep temps down, the new shock was prone to the same sort of shock fade that had plagued the early Yamaha Monoshocks. In addition to the fade issues, the new shock was set up poorly, with too much low-speed compression and not enough rebound damping. Performance started out choppy and only got worse as the damping went away. This was the worst shock in the field in 1987.

|

|

The only chink in the ’87 CR125R’s armor was its poorly-set-up and fade-prone KYB rear shock. This unit was harsh on small chop and prone to kicking in the whoops. It was the worst rear end of 1987. |

|

|

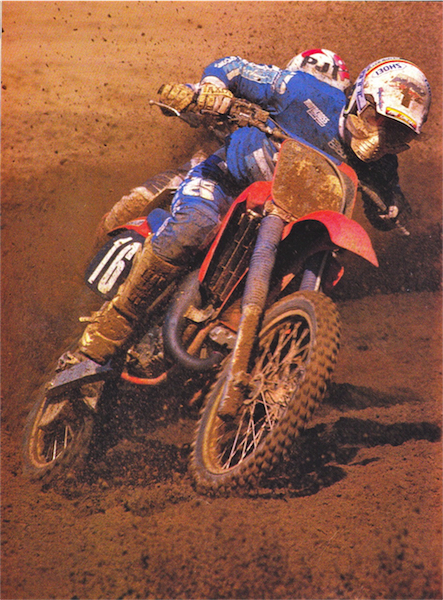

Larry Brooks was not the only privateer to make waves in 1987 on the CR125R.At the 1987 Gainesville National, Ricky Ryan (12) would pull away from the entire field in the first moto and score his first ever win in dominating fashion. Unfortunately, things would go differently in the second moto, as Ryan would catch his leg in a rut and tear the ligaments in his left knee. Even with the injury, Ryan would solider on to finish the race and score a 3rd overall. A week later, a heavily braced Ryan would score the upset of the century, winning the Daytona Supercross on his privateer Honda CR250R. |

While the shock was less than spectacular, the rest of the CR125R package was top of the class in 1987. A new up-the-tank seat and redesigned fuel cell lowered the center of gravity and allowed unencumbered rider movement. In addition to the updated ergonomics, a new frame steepened the head angle half a degree and placed 1.7 more pounds of the motor’s weight on the front wheel. This combined to give the CR the sharpest handling package of ’87. In the corners, nothing could cut under the Honda and it was equally adept diving to the inside or railing the high line. On the faster sections of the course, the CR could be a terrifying handful, with headshake violent enough to remove your hands from the bike in short order. For most riders, this was a trade worth making to enjoy the Honda’s excellent turning manners. Just remember to wear clean underwear in case things do not go as planned.

|

|

Repeat: In 1987, Micky Dymond would fight through an illness at the start of the season, only to catch fire in the later rounds and roost away to a second 125 Motocross title. |

|

|

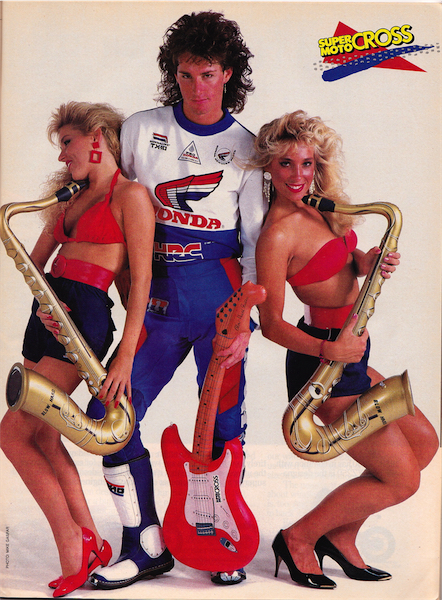

The Champ: Best hair in motocross, hands down. |

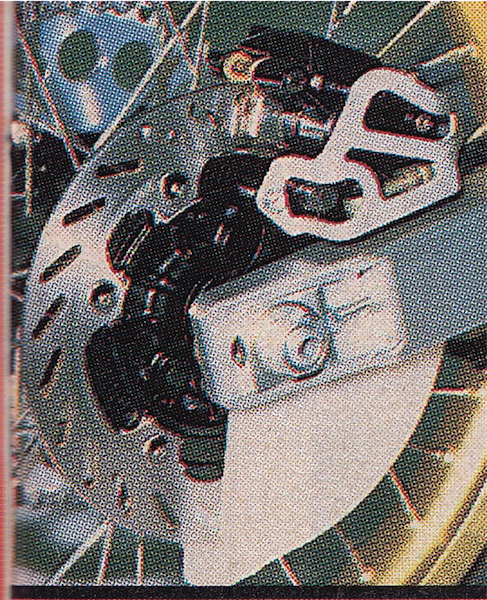

Another big addition for 1987 was the inclusion of a rear disc for the first time. Kawasaki had been the first manufacturer to introduce this feature in 1986 and the rest of the Big Four were quick to jump on the dual-disc bandwagon. Overall stopping power was increased over ’86, but many riders had difficulty adapting to the sudden engagement of the new-school binders. Overall, most riders found the Honda’s more progressive discs easier to adjust to than the grabby KX stoppers.

|

|

The addition of a rear disc brought the CR up to speed with the KX125 for ’87. While less grabby than the Kawasaki unit, the powerful disc on the Honda still took some getting used to after a lifetime of using drum binders. |

While Honda quality in this era was considered at or near the top of the heap, there were still issues with the new CR. During the ’87 season, several riders suffered crank small-end bearing failures (most notably Larry Brooks while leading the South Carolina 125 National) and air leaks led to seizures for many riders. Removing and resurfacing the reed block, while adding a little RTV silicone sealant cured the air leak problem in most cases. Even in 1987, Honda was very sensitive to these issues and quickly took steps to update the offending components. In the end, concerns over the failures of ‘87 would lead Honda to make several changes for the next season that would result in a less powerful ’88 mill.

|

|

Few bikes have ever been so dominant, so praised and so universally loved as the 1987 Honda CR125R. In a decade of great Honda machines, ’87 CR still stands out as the pinnacle of their power. |

In 1987, Honda produced a bike so good, so fast, and so trick that it laid waste to the 125 competition. Yes, its shock was less than perfect; and yes, it did shake its head like a wet dog, but oh boy was she fast. It ripped through the powerband like no 125 before, looked like a million bucks and left the other tiddlers sucking its fumes. It was a bike so good that in its original test MXA proclaimed – “The 1987 Honda CR125R doesn’t just demand to be purchased – it simply knocks down your door, grabs you by the lapels, drags you out to a race track and makes obsolete every 125 that came before. It isn’t slightly better than the ’86 CR125R – it’s head-and-shoulders better. Should you buy one? Heck, buy two. They’re that good.”

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier