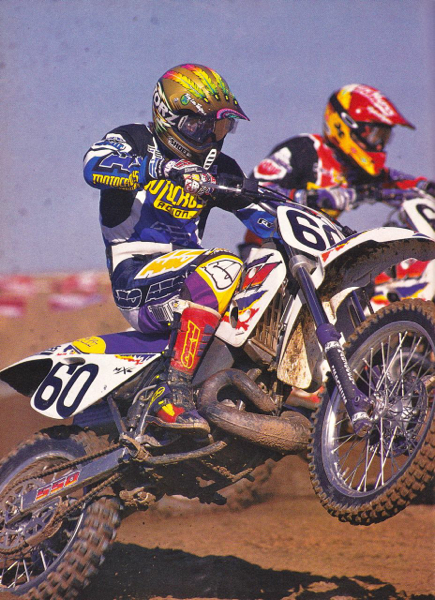

For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at the biggest and baddest of the nineties big bores, the 1995 KTM 550 M/XC.

For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at the biggest and baddest of the nineties big bores, the 1995 KTM 550 M/XC.

By:Tony Blazier

|

| Since the early 90’s KTM has been building niche motorcycles that cater to small, underserved segments of the riding public. Over the years they have produced cool motorcycles in nearly every conceivable displacement to capitalize on the Big Four’s stubborn conformity to established class sizes. The monster-motored KTM 550 was the result of one of these Austrian experiments.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

Today, KTM is riding a wave of success both on and off the track. Their bikes have enjoyed critical praise and the racing teams have captured victories in every off-road discipline under the sun. After all this success, it is hard to remember than not so long ago, the little company from Mattighofen Austria nearly faded out of existence.

|

| The mighty 550 used a bored and stroked 550cc power plant originally designed for a sidecar racer. Considering its size, the motor was actually very easy to ride. Power was mellow, with a slow- metered delivery and torquey feel. The slow revving power actually made the bike better suited for off-road use than MX, but outright horsepower was never an issue.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

Austrian engineer Hans Trunkenpolz founded KTM in 1934. Originally a metal working firm, they had expanded to building motorcycles and scooters by the mid-fifties. Over the decades KTM had enjoyed a good deal of success, but by the early nineties, the company was falling on hard times. The low point came in 1991, when falling sales forced the company into bankruptcy proceedings. As a result of the bankruptcy, the company was forced into a financial restructuring and divided into four separate divisions. The new KTM had separate operations for radiators, motorcycles, bicycles and tool manufacturing. The motorcycle division became KTM Sportmotorcycle AG and focused their resources primarily on the off-road motorcycling market.

|

| It is a good thing the 550’s massive torque made shifting virtually unnecessary, because this baby had more neutrals than a Swiss diplomatic convention. Shifting on the big Ka-Toom was reluctant at best, nearly impossible at worst. Not aiding the situation was a wimpy clutch that seemed better suited to a 125. If you even attempted to slip the pathetic unit it would give up the ghost completely within a few laps.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

One of the innovative ideas the new KTM would employ would be to leverage their smaller, more nimble R&D and manufacturing departments to produce niche bikes in categories not being served by the Big Four Japanese brands. This would lead KTM to develop all sorts of different size machines in every imaginable off road category. If you were looking for something a little different than your average cookie-cutter machine, KTM was quickly becoming the place to shop.

|

| The 550 came out of the hole with a strong but not overpowering blast of torque before lighting the afterburners in the mid-range. On top end the bike petered out well before the rev limiter kicked in. Even with 61hp on tap, its heavy flywheel and mellow delivery made it actually less terrifying to ride than the more racy 500’s from Japan. It was only in the mid-range where the KTM’s displacement advantage was apparent.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

Because KTM was so willing to experiment, you could get your bike in nearly any size or flavor. In the mid-nineties if you wanted to ride a KTM open bike, you could race a 360cc, 440cc, 500cc, or 550cc version. Some years they even offered a 300cc version of the 250 for those looking for a little extra edge. Bikes like the KTM 550 are a perfect example of this “hit them where they aren’t” philosophy.

|

| One feature I absolutely loved on the KTM’s of this era was this super trick “natural” pipe. Before they started chroming their stock pipes, KTM would put a clear coat on the stock natural finish. I’ve always loved the look of a raw two-stroke pipe, and this gave you that look without the hassle of worrying about rust all the time. I wish they would bring this feature back.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

In 1994, KTM USA took a hard look at the falling sales of 500cc motocross machines and decided it was time try something a little different. Their 500 at that point was getting a little long in the tooth, with the basic machine dating back to the mid-eighties. The bodywork had been freshened slightly with the new KTM look debuted on the ’93 250 SX, but underneath that new plastic was a very old school machine. Unfortunately, an all-new bike was not in the budget, so KTM went looking for ways to give their stale open classer a new lease on life.

|

| Interestingly, you could get your KTM open bike in several flavors in the mid-nineties. KTM built a 300, 440, 500 and 550 to suit almost any taste in horsepower. While the 550 was the choice for maximum power freaks, the smaller 440 actually made a better race bike.

Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

The idea the US team came up with was to shoehorn the mega motor out of one of KTM’s European sidecar race bikes into their existing KTM 500 chassis. The bike would be exclusively for the US market (Our love of big motors has always been slightly lost on the Europeans) and look to cater to the horsepower loonies that thought that a CR500 was just not enough. If you were a bigger-is-better kind of guy, KTM had your machine.

|

| The big KTM 550 actually came equipped with three separate mufflers. There was a traditional silencer, a pre-muffler installed in the stinger and a removable Answer Sparky (remember those?). The Answer spark arrestor could be slipped on over the stock silencer for off-road use or removed for MX.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

The heart of the big KTM was its 550cc monster of a motor. The 550 was a bored and stroked version of the original 500 KTM mill that had been used by riders like Kurt Nicoll and Kees Van der Ven for what seemed like centuries. The additional displacement gave the 550 a very different feel than the 500 it was based on. It was equipped with a heavy flywheel and produced a very smooth power delivery. The powerband was actually far mellower than you would normally expect from such a large motor. Low-end power was abundant, but not explosive. The mid-range, however, was where the big 550 really started to flex its muscles. It came on strong and left other 500’s in its dust as the climbed into the meat of the power. After its massive midrange blast, the power tapered off into a lackluster top end. Compared to the Honda and Kawasaki 500’s, the KTM was less powerful at the extremes of its power curve. It was only in the mid-range that its displacement advantage resulted in more power.

|

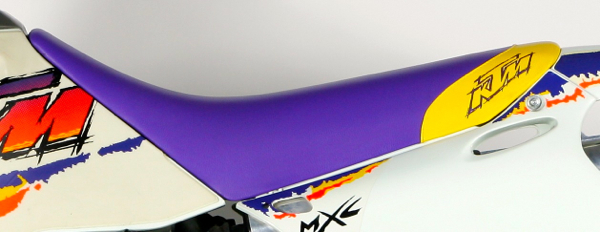

| KTM has always been known for rock hard seats, but this but bruiser took the cake. KTM claimed to use dual stage foam on the ’95 models, but the stages appeared to be quartz and concrete. I don’t know what Austrians grow up sitting on, but they must have the toughest butts in the world. Ten minutes riding on this medieval torture device would have you wishing you had worn padded bicycle shorts.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

The motor on the big Ka-toom was held back somewhat by its recalcitrant drivetrain. Shifting on the 550 was best executed with a heavy boot and a degree of patience. Missed shift and false neutrals were unfortunately a common occurrence. Not aiding the situation was its near worthless clutch that would start slipping at the slightest provocation. Thankfully the bike’s mountainous torque made shifting and abusing the clutch mostly unnecessary.

|

| The highlight of the KTM 550 package for ’95 was definitely the front forks. The switch to Marzocchi Magnum’s from the previous White Power units was a huge improvement. They were exceedingly plush while still absorbing big hits with ease. Aside from their taste for fork seals, they were by far the best forks on any open bike in ’95.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

One of the big changes made by KTM for ’95 was the decision to ditch its long time suspension partner White Power. For years, KTM had suffered scathing reviews in the American press over the performance of Dutch made components. Year in and year out, they were improperly set up and out of step with America’s style of racing. In an attempt to finally appease American consumers, KTM made the switched to Italian made Marzocchi Magnum conventional forks and a premium Swedish Ohlins shock for ‘95.

The performance of the Marzocchi Magnum forks was a huge step up for the Austrian bike. With the change to Marzocchi’s, KTM went from having the worst forks in ’94 to the having the best forks for ’95. The conventional Magnum’s provided a super plush ride on the small stuff while taking the big hits with aplomb. They combined the comfort of the KX with the bottoming resistance of the Honda. The Magnum’s only real flaw was its longevity, as the forks tended to eat seals at an alarming rate.

|

| For ‘95 KTM also ditched the awful White Power shock found on the ’94 550. In its place they installed a Swedish Ohlins unit to handle the rear duties. The Swedish shock was not quite up to the standards set by the excellent Italian forks, but it provided a plush, controlled ride over most surfaces. Its only real flaw was a tendency to blow through the stroke on G-outs and hard landings. With such a heavy bike (242 lbs. with no fuel) a heavier spring was probably in order.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

In the rear, the Ohlins shock was likewise a huge upgrade on the 550. It provided a plush ride over small chop, but was a little too soft on big hits. On G-outs and hard landings the shock tended to blow through its stroke a little too quickly. If you were going to do more off-roading than MX, the setup was near perfect, but for hard core Moto it could have used a stiffer rear spring.

|

| Unlike today, where KTM dominates braking performance, in ’95 they were strictly middle of the pack. The Bremo units did a decent job of slowing down the massive beast, but Honda still had them covered in terms of outright power and feel.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

One area that was not improved on the ’95 550 was handling. The big KTM’s chassis dated back to the mid-eighties and it showed. It was a big, tall and heavy bike that felt even heavier than it was. In turns the bike did not like to be leaned over and preferred to be steered around the outside. The best way to execute a tight turn was to brake-slide in and blast out. The big KTM was definitely more of an old school, “point-and-shoot” open bike. If the track was tight, the bike could be a real handful. It was much better suited to faster, more wide-open layouts.

|

| The 1995 KTM 550 M/XC was an interesting machine. KTM designed it be a jack-of-all-trades, equally at home in the desert or on the track. As a result, it was not spectacular in any one discipline. Its motor was powerful, but tuned more for hill climbing than triple jumping. It’s old school 80’s chassis was likewise more at home dodging Yucca bushes than blasting berms. It was the perfect bike for the guy who rides a little off-road on Saturday and then wants to hit the track for a little practice on Wednesday. In ’95, just as today, if you wanted to find a bike that can do a little bit of everything, KTM was a great place to start.

Photo Credit: Stephan LaGrand |

KTM’s niche marketing plan continues to this day. They produce machines that no one else has the cojones to make. Sometimes they are huge sales success stories, like the current 350 SX-F. While others, like this 550, have faded into obscurity. The KTM 550 M/XC was certainly not about to turn the tide for big-bore two strokes here in the US. It made a good desert sled for riders looking to do more than motocross, but for MX it was a bit of overkill. It was a big, powerful, monster of a bike that demanded respect and required restraint to make work. It may not have been the best or most popular of KTM’s niche experiments, but it showed their willingness to try different things and push the envelope of design. It is that fearless, enterprising spirit that has made them the powerhouse that they are today.