Tony Blazier contributes what he thinks are some of the bikes that changed the sport of motocross in this essay.

Tony Blazier contributes what he thinks are some of the bikes that changed the sport of motocross in this essay.

By Tony Blazier

Motocross is a truly unique sport. It is one of the only motorsports in the world where a competitor can buy a bone stock machine off the showroom floor and with very little modification be competitive at the absolute highest levels. The bike you buy today off the showroom floor is a culmination of over forty years of trial and error. Today’s motocross machines are incredible pieces of technology that combine mind-blowing performance with phenomenal durability. This was not always the case. In the early days of motocross the machines were little more than street bikes with knobby tires. As the sport became more and more specialized, the manufacturers began to design lightweight bikes just for the purpose of racing off road. These early off road bikes were often extremely crude and very fragile. In the early days the key to winning a race was often as much about saving the bike as going fast. Over the years the bikes have gone from claw hammer simple to space shuttle complex. Along the way there have been several seminal machines that have had a profound effect on the sport. These are the bikes that changed motocross.

|

|

Honda enters the the motocross game |

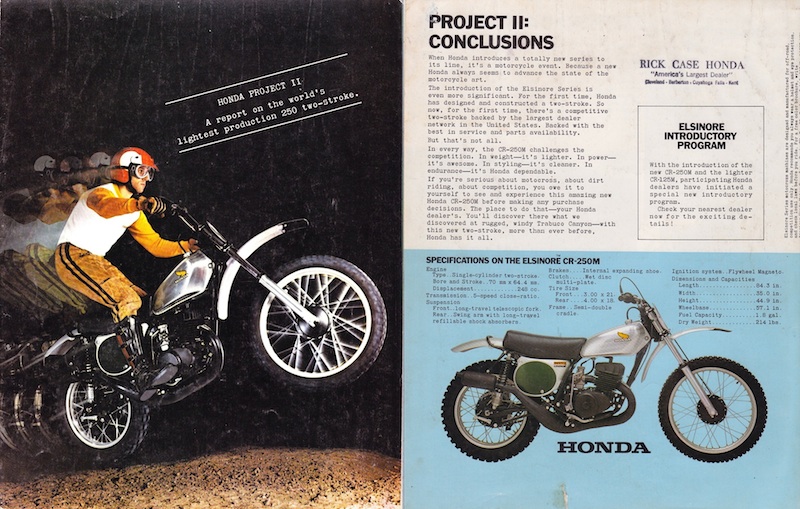

#1 1973 Honda CR250 Elsinore

In 1973 the off road motorcycle world looked a lot different than it does today. Back then it was dominated by European marques like CZ, Maico and Husqvarna. Honda by contrast was a bit of an upstart more known for affordable little scooters than serious motorcycles. Therefore it was a bit of a shock to the establishment when Honda came out with the 73 CR250R Elsinore. The Elsinore was the most serious, race-ready machine made at the time. It was light, fast and in Honda fashion, extremely well made. The Elsinore made extensive use of lightweight aluminum components to keep the weight to a minimum. The Elsinore’s motor was Honda’s first attempt at a two-stroke power plant. The power was hard hitting and as was typical of a straight piston port motor not particularly broad. Some even described it at the time as having a light switch power delivery. Even so the bike was considered very fast for the time. This was a serious race bike and it performed like one. In an era where most bikes required massive modifications to race them, this bike was ready to go right out of the box. The 73 CR250R Elsinore was the first shot in a battle that would see the Japanese totally dominate motocross by the end of the decade.

|

|

The first of the Monoshockers |

#2 1975 Yamaha YZ250

After the huge success of the Honda Elsinore, the other Japanese manufactures were quick to come out with their own “race ready” motocross bikes. Yamaha introduced their YZ line as a more serious alternative to their MX and SC line of bikes. The YZ’s were designed to be no compromise racers and cost accordingly. In 1975 a YZ250 cost $1890.00, nearly twice what a comparable Honda Elsinore sold for. For that money you got the absolute best technology money could buy. Every piece on the bike was trimmed and drilled for lightness. The airbox, side covers and even seat base were fiberglass. The YZ made liberal use of expensive but extremely lightweight magnesium and aluminum for everything from the engine covers to the gas tank. The engine featured an advanced (for the time) six pedal reed valve intake and works bike like chrome cylinder coating for superior power and cooling. The most radical thing about this bike though was the suspension. The 1975 YZ250 was the first production motocross bike to feature a Monoshock.

The single shock on the YZ was laid down and tucked in below the seat. This allowed for more real wheel articulation and action over rough terrain. Where most MX bikes of the time offered a sedate three to four inches of suspension travel the YZ had close to seven inches front and rear. That may not seem like a lot today but in 1975 it really was like owning a works racer. The Monoshock YZ started a trend in motocross where long travel became the order of the day. Within two years of the 75 YZ250’s release nearly every manufacturer had added long travel suspension systems to their bikes. By 1980 most bikes would have close to a full foot of suspension action. Without long travel designs, obstacles like double and triple jumps would never have been possible. This bike was the absolute pinnacle of motocross design in 75 and every guy who has ever dreamed of being the next Jeremy McGrath owes it a debt of gratitude.

|

|

One mighty mini |

#3 1981 Yamaha Y-Zinger

This is the bike that has started more motocross careers than any other bike in history. Long before there were $4000.00 Cobras and KTM 50’s, there was the Yamaha Y-Zinger. The Y-Zinger was released in 1981 and was a wonderful little 50cc fully automatic play bike. The Y-Zinger featured YZ inspired bodywork and graphics and a very modest price tag. It was a bike that could introduce junior to the love of motorcycling while at the same time being safe and easy to handle. The amazing thing though, is what the buying public did with these adorable little bikes. Before you knew it, you had Mini Dads all over the country turning these toys into fire breathing race bikes.

Within a few years of the Y-Zinger’s release it had become THE mini race bike for aspiring motocross racers. It was not uncommon to see Y-Zingers with long travel suspension systems grafted on and highly modified engines pumping out 5 times the stock horsepower. From 1981 until the mid 90’s the PW50, as it was later renamed, totally dominated 50cc motocross racing. Riders from Robbie Reynard to James Stewart all made their names racing on super trick highly modified PW50’s. Eventually the PW50 was eclipsed by purpose built 50cc full on race bikes, but for 15 years the little bike that could reigned supreme.

|

|

The Bombers Baby |

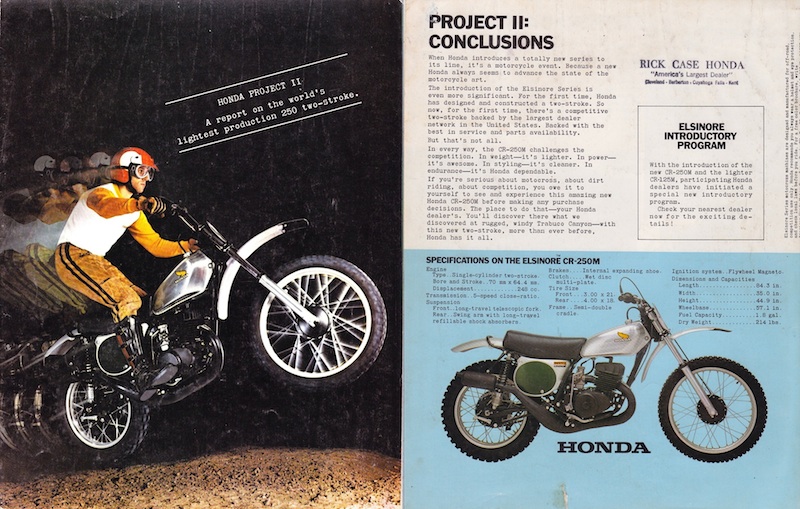

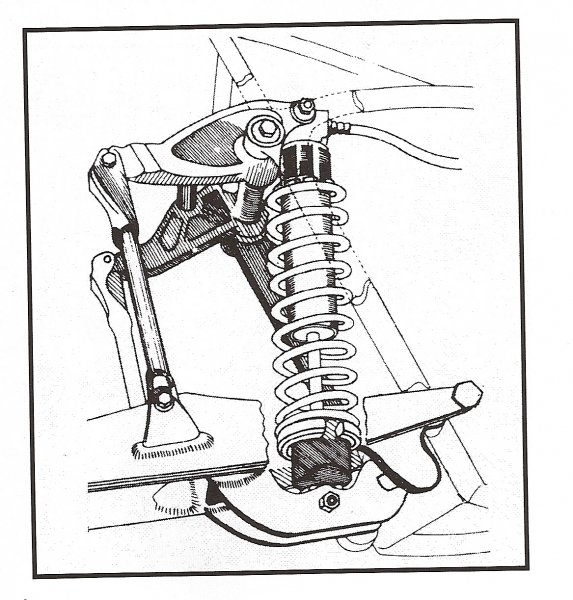

#4 1981 Suzuki RM125

In 1981 Suzuki took the next quantum leap forward in motocross design. They introduced their “Water Cooled” RM125 with in incredible all new “Full Floater” single shock rear suspension. It is hard to imagine now how fast bike design progressed in these early days of American motocross. Just look at a73 Elsinore and then look at this 81 Suzuki. It is hard to imagine these two bikes are only separated by eight years of development. In 81 if you were riding a 73 bike you were riding an antique with literally half the suspension and power. Today if you are on an eight year old CRF450 and race anything short of the pro class you are probably at no disadvantage at all. These days innovation has slowed down to a trickle, but in the 70’s and 80’s motocross technology was moving at a break neck pace.

The 81 RM125 was Suzuki’s first attempt at liquid cooling and that created quite a buzz, but thefeature that everyone remembers about the 81 RM was its incredible rear suspension. By the early 80’s most of the manufacturers were experimenting with using rising rate linkages to augment their long travel designs. The advantage of a rising rate linkage is that it allows the shock to respond more smoothly to small bumps while also absorbing big hits controllably. The 1981 Full Floater suspension system was one of the most complicated ever put into production. Even by todays standards it is extremely complex. The Full Floater used a floating linkage at both the bottom and the top of the shock as well as a set of pull rods connecting the system to the swingarm. It was a Rube Goldberg looking apparatus if there ever was one.

|

|

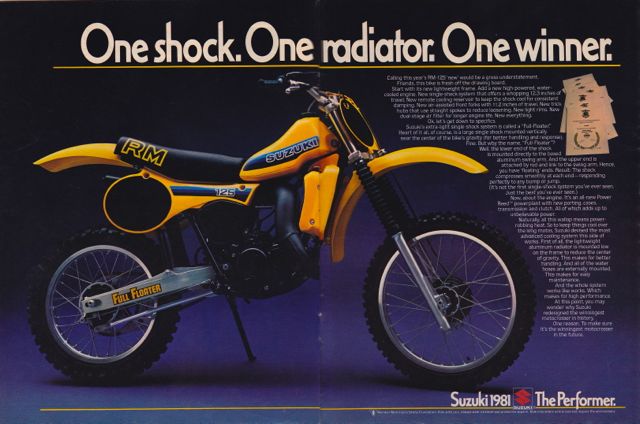

The Full Floater suspension system |

The 1981 Full Floater suspension system

The thing that made the Full Floater famous was the performance. This was the first rear suspension that really delivered on the long travel promise. These bikes absolutely ate the bumps. The full floating design provided the fine articulation to the rear suspension that allowed the shock to be both supple and firm when needed. This suspension design would become the gold standard for the first half of the decade. In the end, the incredible complexity of the Full Floater led to it’s early demise. The design proved too expensive to produce and by 1986 Suzuki had replaced it with a much cheaper and poorer performing design. The name Full Floater would continue to appear on Suzuki motorcycles into the next decade, but they were Floaters in name only. The 81 Suzuki’s were groundbreaking motorcycles that paved the way for the fantastic suspension we have today.

|

|

This bike was less than the sum of its parts |

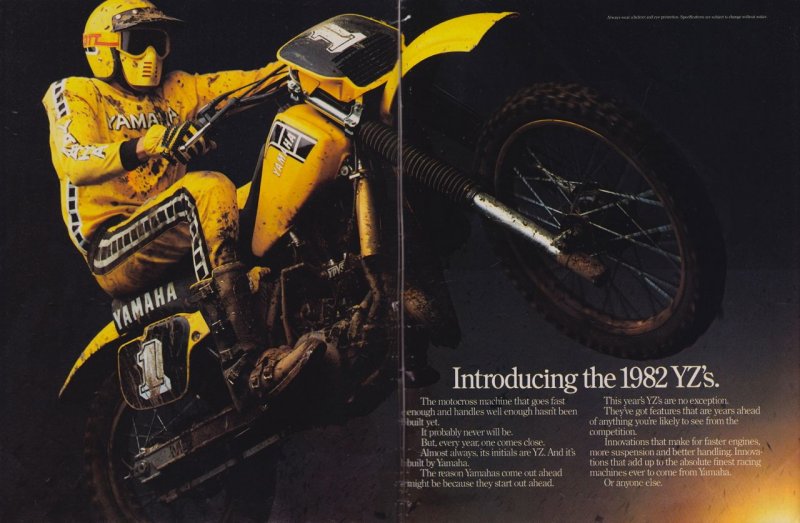

# 5 1982 Yamaha YZ250

Behold the first truly modern motocross bike, the 1982 YZ250. The 82 YZ was the first motocross bike to put together in one bike the key technologies that would shape motocross performance for the next 2 decades. History has largely forgotten this machine. In 82 it was a mediocre performing bike at best. Because of this, people overlook it as the breakthrough bike that it was. For starters it was overweight and underpowered. Add to that a top-heavy feel, bulky ergonomics, and merely passible suspension performance. With all that in mind it is little wonder this bike has slipped into obscurity. Dig a little deeper though and you will discover a bike that planted the seeds for the amazing bikes we ride today. In 1982 this bike was on the very bleeding edge of Moto technology. Features we take for granted today like safety seats and power valves all debuted on this machine. The 1982 YZ250 was the first appearance of the modern two-stroke engine as we know it today.

|

|

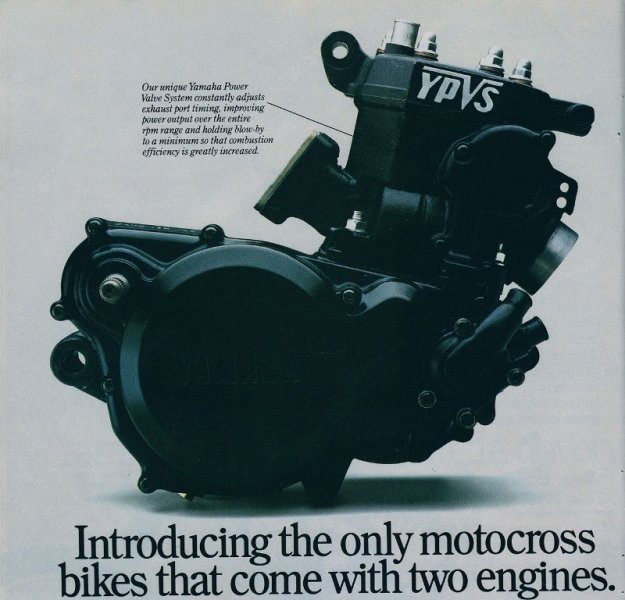

It’s like two, two engines in one! |

The 82 YZ250 and YZ125 were the first production motocross bikes to feature a variable exhaust port. Yamaha called this little bit of techno wizardry YPVS which stood for Yamaha Power Valve System. The YPVS consisted of a small cylinder above the exhaust port that would rotate based on engine RPM. As the YPVS cylinder rotated, it would raise or lower the height of the exhaust port, changing the power characteristics of the motor. Before the introduction of systems like the YPVS, engine tuners had to set up their power plants for either low-end power or top end thrust. With the advent of technologies like the YPVS the motor could in theory be made to do both. The 82 YZ250 was also Yamaha’s first use of liquid cooling on a 250cc MX bike. Now of course all motocross bikes are liquid cooled, but in the early 80’s there was still a great debate going on about the merits of it. Many people believed the added weight and complexity of liquid cooling a 250cc bike far outweighed the benefit of sustained power over the course of a race.

Team Yamaha in fact, actually went back to an air cooled bike to race in the 82 Supercross series. The major problem with the liquid cooling on this bike was the horrible design of it. Yamaha bolted the radiator to the triple clamps and then routed the hoses through the steering head. As a result the YZ carried a great deal of weight very high on the bike. This poor design lead to poor handling and leaks over time. Like most of this bike’s forward thinking technology, it was an excellent idea poorly implemented.

The third piece of major technology debuting on this bike was Yamaha’s first use of a rising rate linkage rear suspension. Yamaha had pioneered the single shock suspension system back in 1975 with their Monoshock but by 1981 they had fallen behind designs like Suzuki’s Full Floater system. To combat this, Yamaha introduced an all new Mono-X suspension system on the 82 YZ’s. It was a much simpler system than Suzuki’s Full Floater but the performance was not nearly as good. The 82 YZ250 was a very advanced bike that fell well short of its promise. Even so it paved the way for the many great motocross bikes that followed in its footsteps. Take a look at the brand new 2012 KTM 250SX and you will still see many of the features pioneered on this bike.

|

|

New color and new low-boy pipe for Honda in ’88. |

# 6 1988 Honda CR250R

By 1987 Honda was on an incredible win streak. Beginning with the 1983 CR’s, Honda had been killing the competition. In 86 and 87 they totally dominated every shootout, in every class from 80 to 500. Adding to that win streak was a remarkable string of National titles in every available class. Riders like Rick Johnson, Ron Lechien and David Bailey destroyed the competition on their RC factory racers. In the mid 80’s Honda had the competition totally covered. Fast-forward to 1988 and Honda introduces one of its most controversial bikes ever, the 1988 CR250R. The 88 CR250R was all-new from the ground up with a radical new design. The motor was a re-tuned version of the world beating 87 power plant but from there on it was clean sheet design. The most noticeable change was in the all-new “low boy” bodywork. This was the first CR to really put to use the lessons learned from Honda’s early 80’s RC race bikes. These bikes featured radically lowered tanks and bodywork to better centralize mass. The 88 CR250R incorporated similar bodywork that was super narrow and low slung to keep the weight as centralized on the chassis as possible. The exhaust pipe was a super trick “low boy” design as well, tucked low down out of the rider’s way. This low sleek bodywork offered the rider the maximum amount of movement and control. The topper to all this was the incredible looks of the machine. Many people, myself included, count these CR’s as one of the most beautiful bikes ever made. The 88 CR250 was like a Ferrari, it just screamed performance standing still.

There is a funny truth about this bike however. In spite of everything this bike had going for it, the 88 CR250R was actually not a very good bike. For 88, Honda had taken the hard-hitting 87 motor everyone loved and neutered it. The explosive hit was gone and replaced with a slow drawn out power delivery that no one liked. The suspension was likewise revised and the new settings were much worse than the all-conquering 87. The shock in particular used an all-new “Delta Link” rising rate linkage designed more for supercross style whoops than the typical chop found on a motocross track. Pro riders could make the bike work but lesser talents were punished. None of that really mattered in the grand scheme of things though. Honda sold thousands of 88 CR’s on reputation and looks alone. Honda brought back the power the next year, but it would take them over a decade to again have suspension as good as the 87 model. The real legacy of this bike was more about a shift in focus by the manufacturers. This was the first of the production bikes made first and foremost to do battle in the stadiums. The 1988 CR250R was a pro-oriented supercross weapon. As the next nine straight Supercross titles would prove, it was a job the CR250R did very well indeed.

|

|

Buck Rogers, your bike has arrived. |

# 7 1997 Honda CR250R

In 1997 Honda took a huge gamble. The 1993 thru 1996 CR250’s, while not perfect, were fantastic racing motorcycles. Those bikes’ only real weakness had been mediocre suspension performance. Other than that they were usually at or near the top of the class in every category. On top of that, with Jeremy McGrath at the controls, Honda had dominated the 96 Supercross season winning all but one race. With that in mind, it took a lot of nerve to totally scrap a popular, proven machine and bring out such a radical departure. The 97 CR250 was all-new from the ground up. The most obvious change was in the frame, which Honda had constructed out of aluminum. This was the first production motocross bike to use the lightweight alloy for its frame material. At the time many road race bikes were already sporting aluminum twin spar frames but the technology had never been tried in the extreme conditions of motocross. The innovations did not stop with the frame however. The 97 CR250R was also Honda’s first attempt at a “traction control” system on a production bike. The CR’s ignition had a sensor built in that could monitor a sudden increase in RPM and if it detected excess wheel spin it would flatten the ignition curve to mellow the power. It was a great idea in theory, but in practice it made no discernible difference in performance. Another first on this bike was the use of a “Power Jet” carburetor. The idea behind this gizmo was to give the motor a little bit of extra fuel under heavy loads. Virtually every two-stroke race bike still uses this technology today. The real star of the show though was the aluminum frame. It made the bike look like something from ten years into the future.

If looks could win races this bike would have been undefeated. Unfortunately Motocross is not a beauty contest and this bikes performance did not match her looks. Because Honda had experienced some broken frames early on in testing they had overbuilt the CR’s frame. It was stiff to the point of being totally unyielding. In motocross, unlike road racing, you actually need the frame to have some flex built in to it. Otherwise the incredible loads put on the chassis by bumps and jumps get transmitted directly to the rider. The unyielding 97 chassis transferred every pebble on the track directly to the rider’s hands. This also exasperated Honda’s already marginal suspension. The result was a rocket fast bike that beat you to a pulp in fifteen minutes. Honda made a huge leap of faith with this bike but the frame technology was still in its infancy and not quite ready for prime time. Much like the 1988 CR250R before it, the 1997 CR was a huge sales success based more on looks and reputation than real performance. It was not until the second-generation aluminum frame made its debut on the 2000 CR250R that the real promise of this forward thinking design started to show itself. Even so you cannot deny the importance of this machine. One look at a modern showroom proves the validity of the concept. Now every modern Japanese motocross bike sports an aluminum frame and they can all be traced back to this machine. The 1997 CR250R may have been a flawed machine but it paved the way for a whole new generation of super strong lightweight chassis’ to come.

|

|

The thump heard around the world. |

# 8 1998 Yamaha YZ400F

In 1996 four-strokes were play bikes plain and simple. Every track had its resident loon who would cram a XR600 motor in some ATK chassis and try and race the thing, but those guys were outliers. In 1996, real men raced two strokes. Well, in the summer of 1997 Yamaha introduced a production version of their four-stroke YZM400 works racer and changed all those perceptions overnight. If there was ever a bike that knocked the motocross world on its collective ear, this one was it. The YZ400F was a full-fledged motocross bike, not some converted play bike. It used a single cylinder version of Yamaha’s Genesis five-valve road race engines. This allowed the bike to turn a very un-XR like 12,000 RPM and not blow itself to pieces. The power started at idle and kept pulling till the rev limiter kicked in. Compared to a 250 two-stroke the power spread felt endless. The YZF used YZ spec suspension and components that cut no corners. This was a serious race bike from the word go. Best of all unlike most of its fragile European competition, the YZ400F was bulletproof.

Not everything was perfect with the big thumper however. For starters, the bike weighed a good twenty-five pounds more than its two stroke competition. This would of course get better with time, but these early YZF’s were heavy beasts. The motor’s unique characteristics took some getting used to as well. For a generation of riders raised on two-stokes things like compression braking and hot start buttons were foreign concepts. Just starting the bike could be a chore for the uninitiated. Early YZF’s also suffered from a nasty hesitation at times if you opened the throttle too suddenly. The revolutionary Keihin FCR carb the YZ400F used was a huge improvement over anything previously offered on a four-stroke, but that hesitation was something riders would have to live with until fuel injection would make its debut a decade later. Even with all its little peculiarities, the YZ400F was a fantastic bike and an incredible engineering feat. For Yamaha to produce such a great bike the first time out with a totally clean sheet design was just phenomenal. This was a bike that no one saw coming and it would take even a powerhouse like Honda four years to even attempt to catch up. If there was ever a bike you could say changed the sport of motocross this one was it.

|

|

Life begins at 14,000 RPM |

# 9 2001 Yamaha YZ250F

In the summer of 2000 Yamaha once again shocked the Motocross world by introducing a 250cc counterpart for their YZ400F. This was in some ways even more of a shock than the YZ400F had been. At this point, none of Yamaha’s competitors had even come out with a bike to compete with the two year old YZ400F, let alone a 250cc version. Now Yamaha was leap frogging over them once again. The YZ250F was even more of a shocker; no one had ever even attempted a high performance 250cc four stroke motocross bike before. The YZ400F was by far the best racing thumper ever, but it had been far from the first. Manufacturers like KTM, Husqvarna, ATK and Husaberg had been making big displacement racing four strokes for years. The YZ400F was just the first one to be more than a niche product. The YZ250F on the other hand was totally new territory. It was basically a given that you needed big displacement to make a four stroke work. The YZ250F was about to rewrite the rulebook on that and a few other things as well. The YZ250F used a smaller version of the five-valve Genesis motor pioneered on the YZ400F. This little motor was an absolute screamer revving to anear splitting 14,000 RPM’s. On the dyno it actually produced less peak horsepower than its 125cc two stroke competitors.

Where the 250F trumped them was in the torque department. The YZ250F pulled harder from a lower RPM and made that power longer than any 125 two stroke could hope to compete with. Of course the truth of the matter was this bike should not have been allowed to race against 125’s at all, but that is a debate for another day. The only real drawbacks this bike had were the same as its big brother. It was of course a good fifteen to twenty pounds heavier than its 125 competition and it was an absolute bear to start. Many a race was lost to the dreaded stalled motor on the early YZ250F’s. The YZ250F, like its big brother, was a truly ground-breaking machine. For better or worse, it completely changed the landscape of small bore racing and overnight made the 125 two stroke obsolete.

|

|

You meet the nicest people on a Honda. |

# 10 2002 Honda CRF450R

It really is incredible what a lead Yamaha had on its competition with the 1998 YZ400F. It took a full four years for any of its Japanese competitors to come out with a bike to compete with it. Kawasaki in fact would not produce a competitor for an incredible eight years. That is just how badly Yamaha caught its competition off guard in 1998. It was not until 2002 that Honda finally brought out its highly anticipated YZF competitor. The 2002 CRF450 was a completely new design and to their credit, a very different one than Yamaha had used. Not content to just turn out aYZ400F clone, Honda had gone back to the drawing board and come back with a very different take on the big bore four-stroke race bike. Unlike the YZF, the Honda used a single overhead cam to make the motor more compact. The CRF also had separate chambers for engine and transmission fluid. This allowed for less contamination of the engines oil and with no external oil tank, lighter weight. The frame was constructed of aluminum and now on in its third generation, it was a huge improvement over the horrible 1997 chassis. By this point Honda was finally starting to get their suspension figured out and it was a far cry from the bone jarring junk they had used throughout the 90’s. Honda had taken a hard look at the YZF before building their version and addressed many of the issues that plagued the Yamaha. Unlike the YZF there was no drill or ritual to get the big Honda started. Like a two-stroke, you could just kick it and go. Once running, the Honda had much less compression braking than the YZF, which made it an easier transition for four-stroke newbies.

The Honda also had much less of the bog or hesitation that had plagued the YZ400F and YZ426F. This was very important because anyone coming off a two stroke would be more accustomed to the lighting fast response a good smoker provides. The last thing Honda tried to address on the CRF450R was size and weight. Any way you slice it the YZ400F and YZ426F were big bikes, both in size and weight. They were heavy bikes and really felt like it when you rode them. The CRF450R by comparison felt much more like a traditional two stroke 250 in size. The ergonomics were more compact than the Yamaha and the bike did indeed weight less. All these little improvements added up to a much easier bike to live with than the Yamaha. Honda had really gone out of their way to make a bike that would be easier for a two-stroke rider to get on and feel right at home. I think that is why this bike belongs on this list. The YZ400F was indeed the first bike that signaled a change in the racing landscape. The 2002 CRF450R however was the machine that really heralded the end of the two-stroke’s domination of racing.

The YZ400F, while a big hit, was still a bike that appealed to a smaller audiance. The CRF450R on the other hand became an everyman’s bike. By 2004 it was not uncommon for nearly half the bikes at a local track to be CRF450R’s. They were everywhere. By building a bike that kept the good points of a four stroke while getting rid of ninety percent of the annoyances, Honda put the nail in the coffin of the two stroke race bike. Like any bike, the 2002 CRF450R was not perfect, but it was a bike that really changed the face of the sport as we know it today.