For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the all-new 1996 Suzuki RM250.

By: Tony Blazier

Totally redesigned for 1996, the all-new RM250 proved to be the best yellow deuce-and-a-half in nearly a decade. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Totally redesigned for 1996, the all-new RM250 proved to be the best yellow deuce-and-a-half in nearly a decade. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The Suzuki RM250 was all-new for 1996 and a major departure from the bike it replaced. The ’93-’95 RM250s had been pretty poor machines compared to their rivals. Their motors had been long on punch but short on breath, making them difficult to ride. The handling had been even worse, with an unsettled feel and terrible stability. While Suzuki’s 125s were acknowledged to be some of the best in the class, their 250s were relegated to the back of the pack. Suzuki hoped their radical new RM250 would be the machine to finally repair their tarnished 250 class reputation.

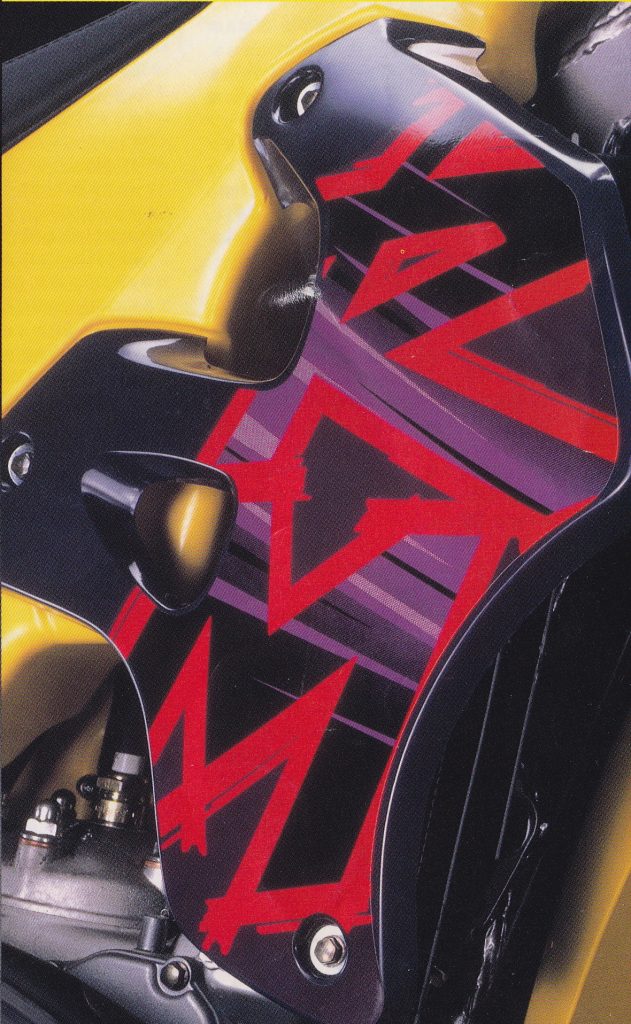

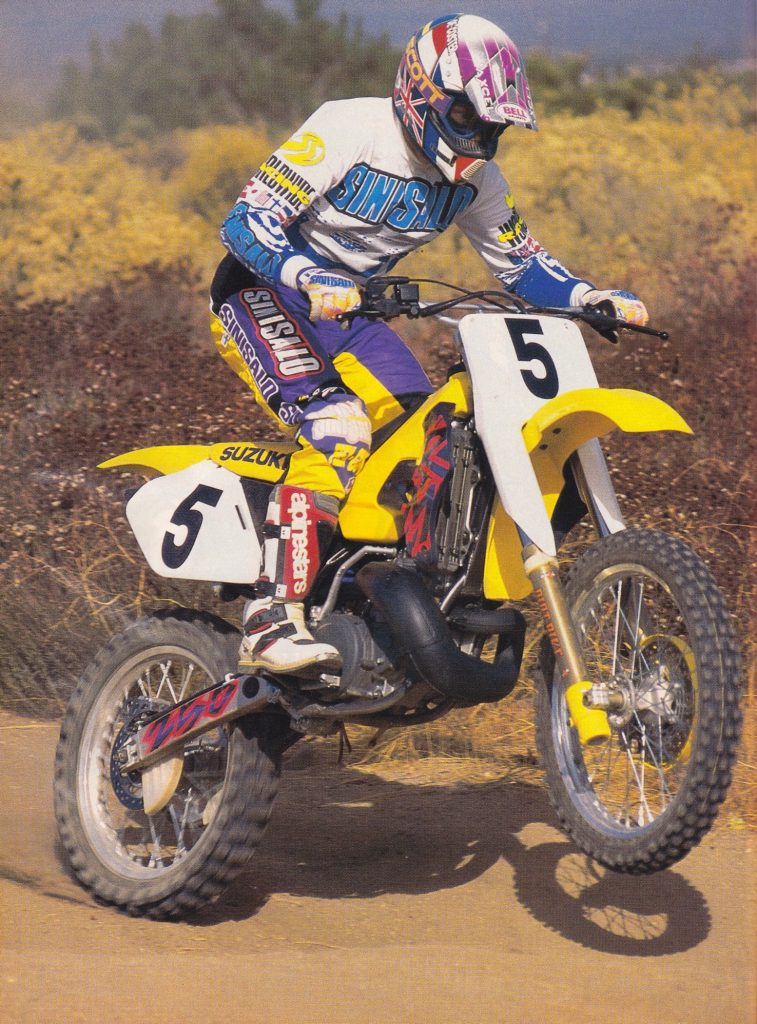

Even the all-new RM was not immune to the rampant purple craze that infected the motocross industry in the mid-nineties. For some unknown reason, every manufacturer felt an uncontrollable need to plaster their bikes with various shades of grape. Believe it or not, this RM graphic was actually tasteful by nineties standards. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Both the RM125 and RM250 were all-new designs for 1996. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1996, the Honda CR250R was considered the gold standard in 250cc motocross motors. The CR produced an extremely broad, torquey power delivery that was both fast and brutally effective. This was in direct contrast to the short abrupt power delivery that had become as the trademark of Suzuki’s 250 motors. Starting with the 1989 model, Suzuki had been using a case-reed design on its RM250s to less than stellar effect. The case-reed design, while very effective on small motors like 125s, had not proven particularly successful at providing a broad power curve on 250s. Too often, it resulted in a short and abrupt style of power that made the bike difficult to ride. Suzuki’s ‘89 – ’95 RM250’s all had offered this quick revving, staccato style of power. For ’96, Suzuki looked to ditch this gun-and-run style of a motor in hopes of taking down the class-leading CR250R.

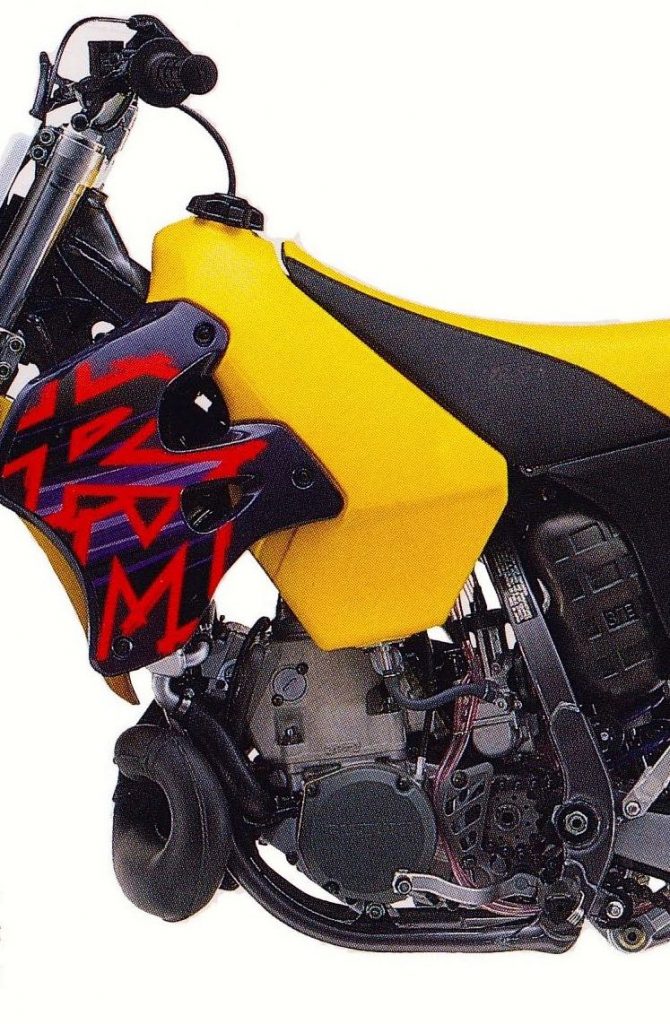

Suzuki aimed for the all-powerful Honda CR250R motor with their new engine and just missed the mark. The powerband was very similar to the CR’s broad and torquey power output, but with less thrust at every point on the curve. While it was not the most powerful motor in the class, the new RM mill was competitive and a major improvement over previous Suzuki efforts. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Suzuki aimed for the all-powerful Honda CR250R motor with their new engine and just missed the mark. The powerband was very similar to the CR’s broad and torquey power output, but with less thrust at every point on the curve. While it was not the most powerful motor in the class, the new RM mill was competitive and a major improvement over previous Suzuki efforts. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The 1996 RM250 featured an all-new motor design that did away with the case-reed intake entirely. In its place, Suzuki went back to a more traditional cylinder-reed intake that they hoped would broaden the power over previous designs. When studying the new motor, it became pretty clear that Suzuki had looked to the CR250 motor for inspiration with their new motor design. The internal dimensions on the RM were identical to the CR and even the kickstarter and pipe appeared to have been lifted right off the red machine. The motor’s only truly unique feature was its water pump, which was housed internally instead of being bolted to the outside of the cases. This gave the motor a slightly odd appearance and a unique sound, but also prevented any potential crash damage to the normally vulnerable pump.

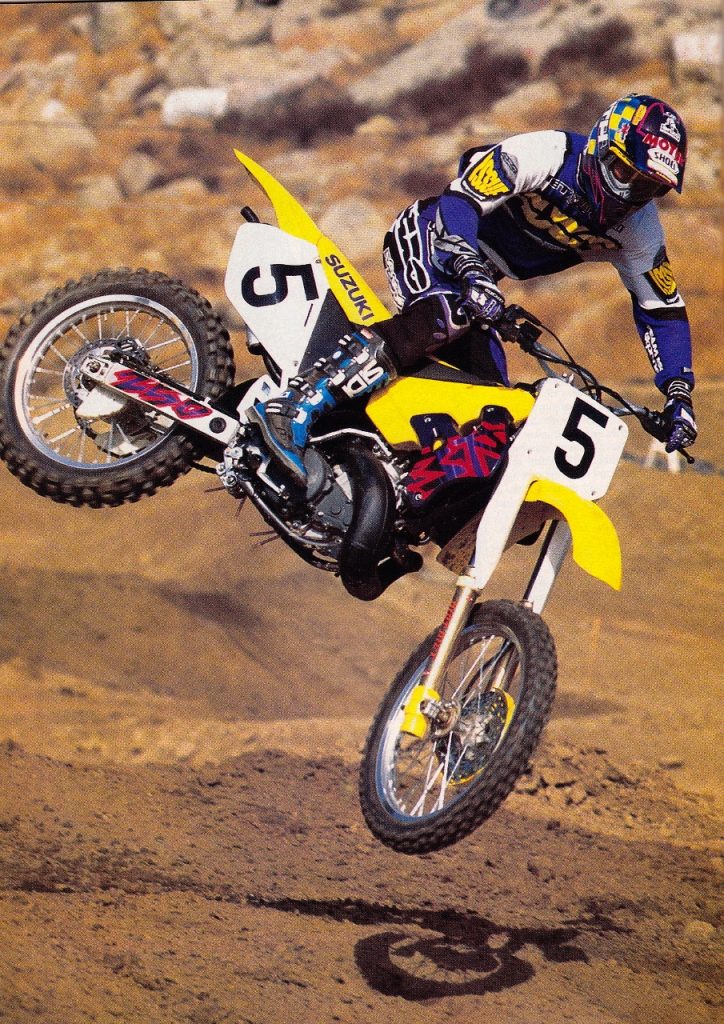

The biggest news on the ’96 RM was probably the all-new 49mm Showa conventional forks. They provided a plush feel and gobbled up everything on the track with aplomb. For anything short of Supercross they were absolute magic. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The biggest news on the ’96 RM was probably the all-new 49mm Showa conventional forks. They provided a plush feel and gobbled up everything on the track with aplomb. For anything short of Supercross they were absolute magic. Photo Credit: Suzuki

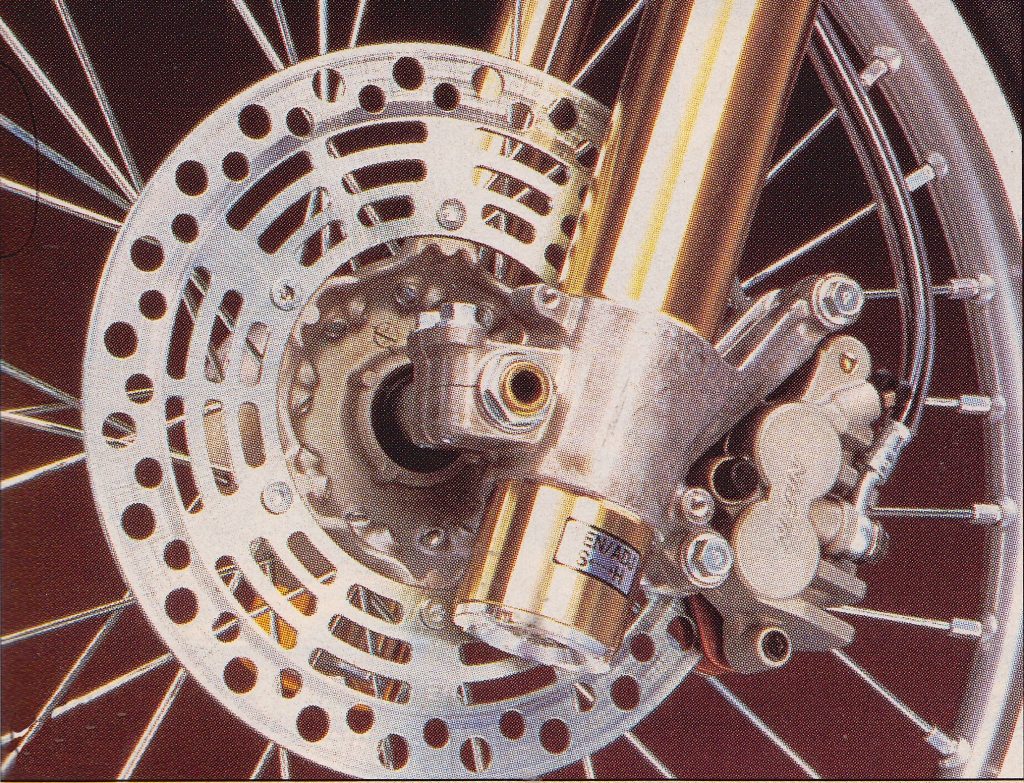

The most radical departure in the RM’s design was Suzuki’s decision to go back to a conventional fork on the new machine. After six years of up-side-down designs, Suzuki’s new forks were actually a bit of a novelty in ’96. The main advantage of USD forks was their inherent stiffness that allowed pros to literally smash into obstacles. Unfortunately, that rigid feel that pros appreciated, tended to punish riders of average skill. The new 49mm Showa conventional forks were designed to bring back some of the plushness of older designs, while still offering the rigidity the pros desired.

One of the major complaints about conventional forks had always been their propensity to get hung-up in ruts. In order to address this, the RM’s the new 49mm Showa conventional forks employed a design with very little overhang below the front axle. Photo Credit: Suzuki

One of the major complaints about conventional forks had always been their propensity to get hung-up in ruts. In order to address this, the RM’s the new 49mm Showa conventional forks employed a design with very little overhang below the front axle. Photo Credit: Suzuki

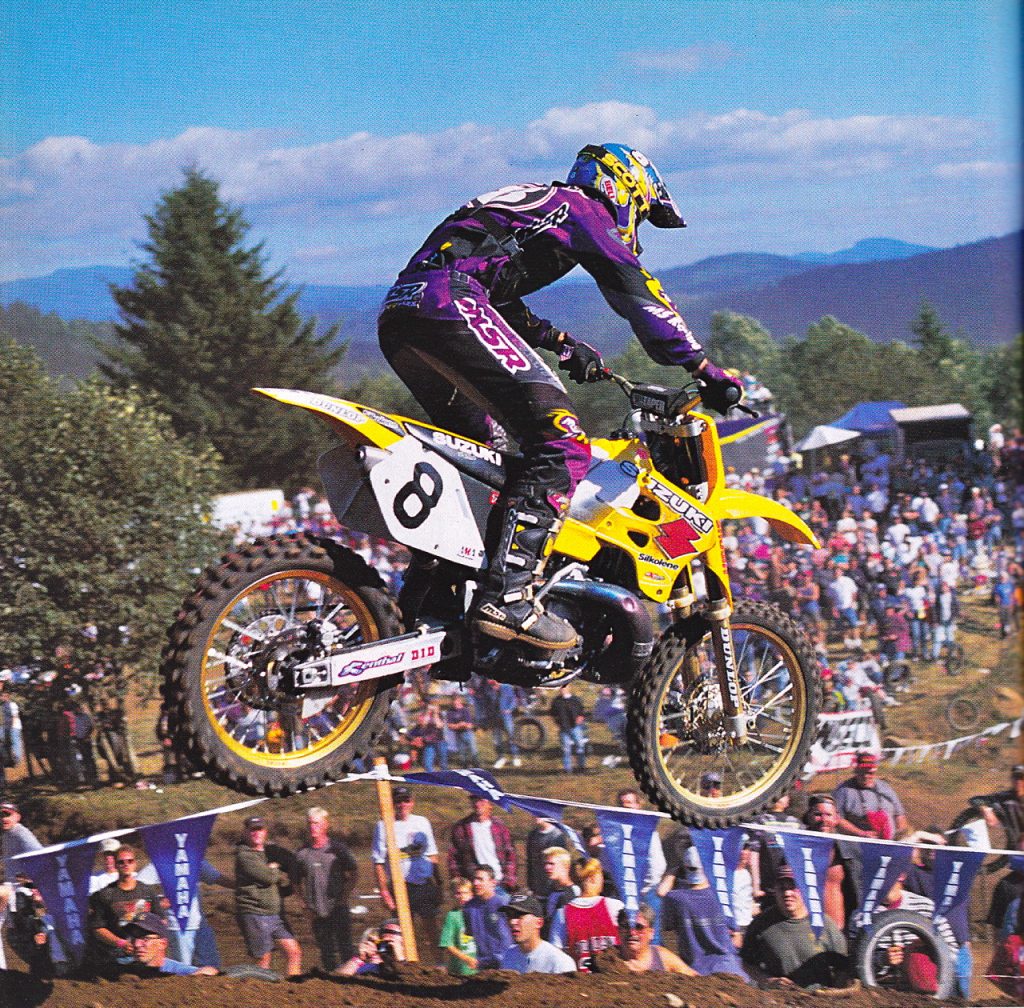

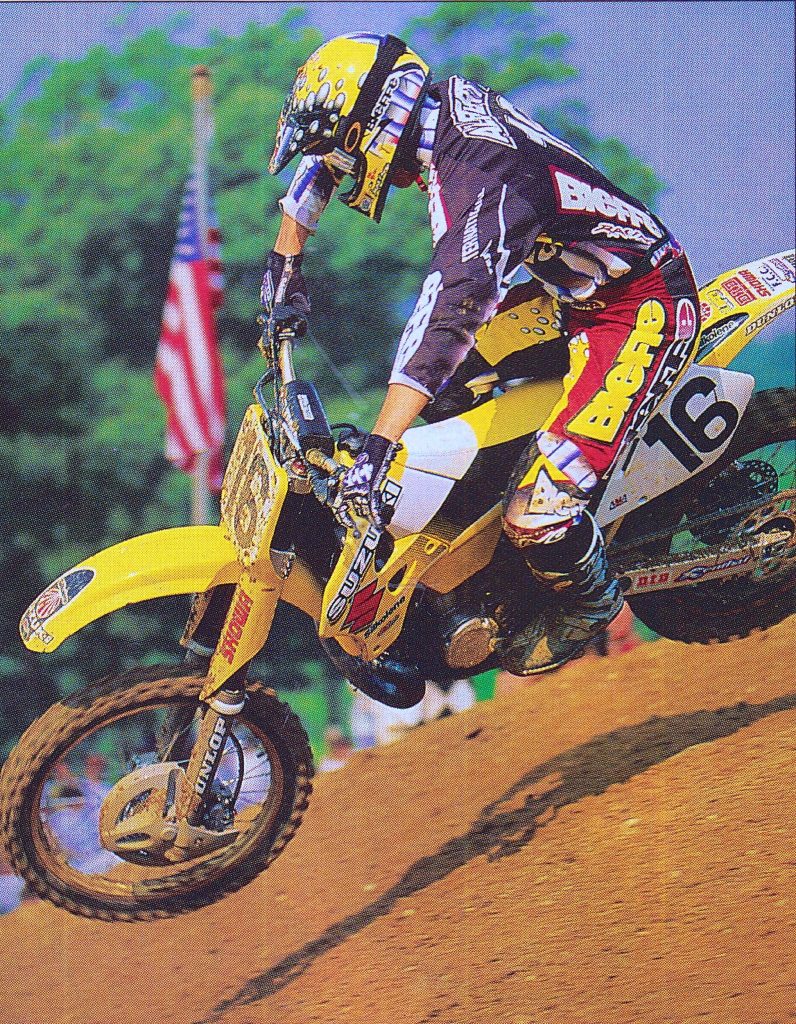

After several years on Kawasakis, Mike LaRocco had a difficult time adapting to the new RM250 in 1996. Even though it was clear he was not a fan of the new machine, he would end up scoring an overall victory at Washougal in August. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

After several years on Kawasakis, Mike LaRocco had a difficult time adapting to the new RM250 in 1996. Even though it was clear he was not a fan of the new machine, he would end up scoring an overall victory at Washougal in August. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The rest of the RM’s new chassis was very conventional for the time. The frame was constructed of high-strength chromoly steel with a large center backbone and removable rear alloy sub-frame. Out back, the RM featured an all-new Showa shock and totally redesigned linkage. Matching the new chassis was completely reworked bodywork that cleaned up the lines and gave the new machine a very Honda-like appearance. Probably the most unique feature in the appearance of the new RM was its new front number plate. Instead of using fork boots as had been the practice in the eighties, Suzuki decided to design and all-new oversized plate that included extensions that covered the upper portions of each fork leg. While not everyone approved of the front plate’s appearance, there can be little doubt that it set the new machine’s looks apart from the crowd.

In 1996, Suzuki’s engineers moved the water-pump from the outside of the cases to inside. This was done to simplify packaging (fewer hoses) and lessen the change of suffering damage in a crash. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrande

In 1996, the Factory Suzuki squad ditched the stock purple tidbits and went with a much cleaner all-yellow motif. I had this factory-replica N-Style kit on both of my ’96 RMs and I really think it improved the looks of the stock machines. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the track, the new RM proved to be a serious improvement over the lackluster machine it replaced. The new motor pulled strongly off the line and produced a solid mid-range burst. Top-end power was not astounding, but the overall powerband was wide and easy-to-manage. Compared to the ’95 RM, the new motor ran much smoother and pulled over a wider range. It lacked the holeshot-ripping midrange blast of the CR250R, but was more than competitive below the pro class. With its excellent clutch action and smooth-shifting five-speed, the ’96 RM mill was the best Suzuki 250 power-plant since 1988.

On the dyno, the 1996 RM250 motor was no superstar. In the midrange, it gave up several horsepower to the competition and only caught up at the upper reaches of the curve. On the track, it was more competitive, with a broad pull and smooth delivery. For pro racing, it was not going to cut it, but for the average Joe, it was a good motor. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Greg Albertyn had some truly spectacular get-offs on the new RM250 during the ’96 season. At the Houston Supercross he got ejected off the bike 30 feet in the air while jumping a huge quad. At High Point, he appeared to be headed to his first US win when he literally fell off the back of his bike in a rutted corner. Even though he had some hard crashes, the tough South African never failed to get back on the bike and keep trying. His perseverance would finally pay off with a 250 National Motocross title for Suzuki in 1999. Photo Credit: Donn Maeda

Greg Albertyn had some truly spectacular get-offs on the new RM250 during the ’96 season. At the Houston Supercross he got ejected off the bike 30 feet in the air while jumping a huge quad. At High Point, he appeared to be headed to his first US win when he literally fell off the back of his bike in a rutted corner. Even though he had some hard crashes, the tough South African never failed to get back on the bike and keep trying. His perseverance would finally pay off with a 250 National Motocross title for Suzuki in 1999. Photo Credit: Donn Maeda

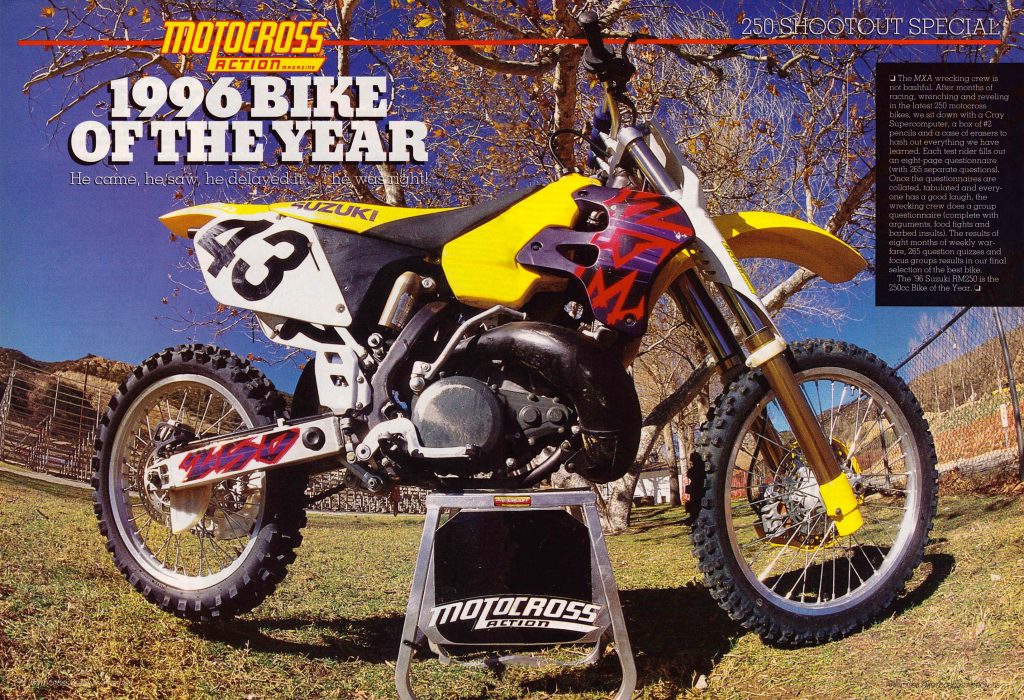

While history has not been kind to this generation of RM250 (in large part due to the criticisms of Suzuki’s factory team riders in ’96 and ’97), it was actually very well received in the motocross press of the time. All of the magazines declared it a huge improvement over 1995 and MXA even proclaimed it the Bike Of The Year over history’s more beloved 1996 CR250R.

While history has not been kind to this generation of RM250 (in large part due to the criticisms of Suzuki’s factory team riders in ’96 and ’97), it was actually very well received in the motocross press of the time. All of the magazines declared it a huge improvement over 1995 and MXA even proclaimed it the Bike Of The Year over history’s more beloved 1996 CR250R.

On the suspension end of things, the RM offered one of the best overall packages of 1996. The new 49mm conventional forks were incredibly plush and well controlled. On the track, they absorbed everything in their path and proved to be the best silverware in the 250 class. Interestingly, today these forks are thought of as failures, but that was more due to external forces than the performance of the hardware.

Light feeling in the air and nimble on the ground, the 1996 RM250 offered one of the best handling packages of 1996, Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1997, Jeremy McGrath switched to Suzuki of Troy at the last minute and it was no secret that he was not a fan of the works version of the Showa conventional forks. For his skill level, they were just not stiff enough. This led to a rash of bad press as LaRocco, McGrath, and Albertyn switched back to inverted sliders on their factory machines. In truth, the works forks had nothing to do with the stock hardware, but the move put pressure on the marketing team to switch back. The other factor in their demise was their uniqueness. With all the other Japanese manufactures sticking to USD forks, it became hard for Showa to justify the expense of developing technology that could not be amortized over a large number of units. Eventually, Suzuki would cave to market pressure, and in 1999, switch back to inverted forks on both of their full-size RMs.

While not as well sorted as the forks, the Showa shock on the 1996 RM worked well enough to be raced in stock condition. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In the rear, the RM’s new shock was not quite up to the standards of the forks. It absorbed large and small hits easily and provided a plush feel, but some riders felt the rear was a bit floaty and underdamped at times. In showroom-stock condition, the shock was stiff on compression and light on rebound. Thankfully, most of this could be remedied by adjusting the compression and rebound clickers. With a little fine-tuning, the rear could be made to work very well for most riders. Pros would still want stiffer springs and more control, but for most riders, the shock could do the job without paying for a re-valve.

The Man: Roger DeCoster (here riding the new RM for Dirt Bike magazine) played a major role in the development of the new RM. One of Honda’s most valuable assets in the eighties, Suzuki hoped to repeat that magic on yellow in the nineties. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Of all the improvements made for 1996, the most dramatic turn around was probably in the handling department. In 1995, the RM250 had been the worst handling bike on the track. It was a disjointed, unsettled and a complete handful. For 1996, all of that was in the rear view mirror. The new chassis was night-and-day better than ’95 and one of the best handling packages of 1996. It offered the turning prowess of the Honda and the straight-line stability of the Kawasaki. The light feeling and tight handling RM250 was the jack-of-all-trades in the motocross wars for ’96.

The 1996 RM250 stands as one of the most misunderstood and unfairly maligned machines of its era. At the time, it was appreciated and praised for its comfort and performance, but a lack of success at the pro level has forever stained it as a failure that it never was. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1996, Suzuki launched its most successful 250 design in nearly a decade. Well-suspended, tight handling and easy-to-ride, it was a great bike for the masses and a huge upgrade over previous Suzuki efforts. Unfortunately, over time, most of those virtues have been obscured by the controversy that plagued the machine at the pro-level. While it may not have been the best bike for Albee, LaRocco and MC, it was a great bike for the rest of us mere mortals.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram – @TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com