For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the 1981 Husqvarna 430CR.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the 1981 Husqvarna 430CR.

By: Tony Blazier

|

By 1981, the dominance of the traditional European motocross powerhouses was all but a memory. The influx of cheaper, more reliable and often better performing bikes from Japan had whittled their once market-leading position down to a mere sliver. For Husky, the ’81 430CR would be a last hurrah of sorts – one last sentimental victory over the relentless Japanese onslaught. |

By the start of the 1980’s, the sport motocross was knee deep in the middle of a Japanese invasion. After decades of European domination at all levels of the sport, the upstarts from the Far East began an onslaught in the mid-seventies that would see them eclipse their Old World rivals in nearly every division. While the 250 and 125 class would quickly fall to the land of the rising sun, the open class would remain the sole hold out of the Europeans. Brands like Maico and Husqvarna would find it difficult to keep up with the rapid rate of innovation common to the small-bore classes. In the slower paced world of Open bikes, however, their Old World engineering and big bike expertise would at least stave off the Big Four for a few more years.

|

One of the innovations made to MX machines toward the later part of the seventies, was the repositioning of the countershaft sprocket. Early long-travel machines had suffered issues maintaining the proper chain tension throughout the full range of their movement, leading to potential failures. As the manufacturers got more experience with the new technology, they found that moving the countershaft very close to the rear suspension pivot point, solved most of these issues. |

In America, 125 and 250 class were quickly gaining in prominence by the later part of the 1970’s. As new bikes became more powerful and better suspended, buyers began to gravitate away from big burly Open class machines. In America, the 125 class was actually the hottest class by a wide margin. In Europe, however, things were a little different. There, the Open class was still considered the premier class. In the world of Grand Prix Motocross, the 500 was King, while the 250 and 125 divisions were merely thought of as stepping stones to the real man’s class.

|

Time has a funny way of changing one’s perceptions of things. At the beginning of the motocross movement here in America, Husqvarna was THE brand to have. They had race ready bikes and a powerful racing presence to back it up. Eventually however, an onslaught of competition, and a lack of innovation took them from top dog to also-ran. By the time the mid-eighties hit, the once proud brand was on the ropes and ripe for a take over. While the Husqvarna name is still involved in the sport, its many buyouts and odd design choices have relegated it to a niche product here in America. Perhaps it will take the Germans to bring the pride of Sweden out of the shadows and into the limelight once again. |

With so much focus on the 500’s, it was not really surprising that the traditional European brands tended to take the Open class more seriously. Whereas the Japanese focused their efforts on the more lucrative small bike classes, the Old World manufacturers specialized in the big bores. To them, the 500’s were prestige machines- much like a NSX super car is to modern Acura. They may not sell in huge amounts, but they make a statement about your company and serve as a halo for the brand. The Japanese, on the other hand, often treated the 500 class as an afterthought. So much so, that Honda did not even bother to produce an Open bike until 1981. Throughout the seventies, the Japanese seemed content to crank out inferior Maico and Husky clones, never quite capturing the mystique of the originals. In the decade to come, however, the sleeping giant in the East would pour their considerable monetary and engineering resources into dominating the last bastion of the old guard of motocross.

|

For ’81, Husky introduced an all-new engine for their Open class machine. The new mill featured lightweight magnesium cases, a primary kickstart (which allowed for starting the bike in gear), a reed-valve and six-speed tranny. At 430cc’s, the Husky’s motor was the smallest of all the ’81 “500’s”. It was no arm-jerking powerhouse, but it possessed a super-wide and easy-to-ride powerband. With its smooth character and snappy response, the 430CR was second to only the trench digging Maico 490 Mega 2 in the overall ’81 power standings. |

While the name Husqvarna has been an ongoing part of motocross for more than 60 years, the machines sold today actually have very little in common with the bikes that made the brand famous. Husqvarna’s original parent company actually dated all the way back to the late 1600’s. Originally arms manufacturer, they had diversified over the years into several different operations. The motorcycle division began operations in 1903, and continued producing machines until the operation was sold to the Italian motorcycle giant Cagiva in 1987. Cagiva would move production from Sweden to Italy and integrate many of their own designs into the Husky model portfolio. During Cagiva’s ownership, the brand was able to capture several World Motocross Titles, but Husky was never able to recapture their lost market share in the US. In 2007, German automotive giant BMW would purchase Husqvarna for a reported 93 million euros. Under BMW’s ownership, Husky’s have become interesting bikes, that ooze style and march to the beat of a different drummer. They are sleek and edgy, with innovative designs and aggressive styling. In short, the German Husky of 2012 is nothing like the Swedish Husky of 1981. In 1981, Husky’s were Old World Swedish all the way.

|

Unlike most other European manufacturers, the ’81 Husky eschewed an old school Bing carburetor in favor of a more modern Mikuni mixer. While most 500’s of this era struggled with jetting issues, the clean running Hooska ran crisply and pulled smoothly from bottom to top. Faster than a 250, and easier to manage than a full 500, the 430CR was the just right motor of ’81. |

As pioneers in the early days of international motocross, the Swedish machines had claimed countless off-road and motocross titles by the mid-seventies. Husky’s were loved for their superb handling, and many early Japanese designs drew their inspiration from the Swedish marque. By the late seventies, however, the Japanese were quickly chipping into Husky’s lead, and the once premier motocross machines were starting to feel behind the times. In many ways, the 1981 Husqvarna 430CR would be the last hurrah for the once great Swedish brand.

|

Unlike most manufacturers, Husqvarna actually took it upon itself to design and produce the 430CR’s front forks. The 40mm units cranked out nearly a foot of excellent, smooth travel. Much like the motor, their relatively small size was no hindrance to the bikes performance. In ’81, these were the best forks in the Open class. |

In 1981 there were two distinct schools of thought in Open class design (much like today’s 450 vs. 350 controversy). On the one side, you had the less is more philosophy, that believed a 500 was actually better off being closer to a 400cc machine. Then you had the bigger is better crowd, who felt an open bike worked best when it could yank a small home off its foundation (exemplified best by the mega-motored Maico 490 and KTM 495). The advantage of the smaller motor was, of course, ease of use. While the big-bore crowd got their jollies throwing mega roosts and challenging friends to impromptu drag races. In the 500 power sweepstakes, the ’81 Husqvarna 430CR was the perfect example of the less is more philosophy.

In 1981 the Husky’s 430cc mill was the smallest of the major manufacturer’s 500 class offerings. It pumped out just over 43 HP, which was competitive with the Honda CR450R and Suzuki RM465, but well shy of the 50 HP cranked out by the Maico and KTM. While raw HP figures always sound good in ad copy, they often do not tell the whole story. The strength of the ’81 Husky’s motor was is versatility. A rider on a 430 could actually use every ounce of power the 430cc mill put out. Unlike most 500 motors of the day, it was blessed with an excellent low-end, tractable mid-range and a strong top end-pull. Where both the Honda and Suzuki motors were decidedly one dimensional, the Husky exceled at every phase of the powerband. It could be lugged or revved, with equal effectiveness. In addition to putting out an excellent spread of power, the Husky’s Mikuni carb’d and reed-valved mill carbureted cleanly (something none of the Japanese 500’s could say) and avoided the pinging and blubbering common to big bores of the time.

|

If there is one design element that was the trademark of early Husqvarna’s, it was their iconic aluminum tank. Husky would continue to use these super-cool alloy jewels long after the rest of the industry had moved on to plastic. It was an old school touch that set the bike apart from its Japanese rivals. |

With the inclusion of its six-speed tranny, the 430CR was by far the most versatile 500 you could buy in ‘81. With the Honda’s four-speed you were limited strictly to MX use, but with Husky you could ride desert, MX and cross-country all on the same machine. While it might not have made the most outright horsepower in ’81, the Husky’s sweet mill may have actually been the best overall package. The ground pounding Maico 490 and KTM 495 had it more than covered in terms of raw power, but its ease-of-use and versatility made it tough to beat.

|

|

In the years since the ’81 430CR made its debut, much has been written about its main competitor, the 1981 Maico 490 Mega 2. MXA has gone so far as to call the Mega 2 the greatest motocross bike ever. With praise like that, it is not hard to see how the mid-sized Husky could fall into the shadow of the big German. In truth however, it was actually the Swede that took home the honor of MXA’s top 500 class machine of ’81. While it lacked the stump pulling torque of the mighty Mega 2, it had superior suspension, and none of the Maico’s annoying quality issues. Once sorted out, the Teutonic Tractor may have held more potential, but in box-stock condition, the Husky was actually the better machine. |

Unlike most manufacturers that subcontracted out their front fork development to others (Kayaba, Showa, Ohlins ect.), Husqvarna actually developed their suspension in house. This meant they had much greater control on the final product, but it also meant they typically had fewer resources than the bigger suspension companies. Interestingly, the Swedes actually beat the established players at their own game in ’81. The forks on the 430 were smallish for the time 40mm in diameter (most of the competition had moved onto 43mm front ends by ’81) and offer just under a foot of travel. While the forks may have looked small on paper, on the track they were excellent. They provided a plush ride and absorbed small chop and big hits in stride. They were worlds better than the poorly set up Showa and KYB components found on the Japanese bikes and more than a match for Maico’s lackluster ’81 offerings.

|

In 1981, monoshocks and big, beefy alloy swingarms were all the rage. Every year brought with it newer and more complicated suspension designs, all in search of the perfect combination. While the Japanese experimented with all manner of Rube Goldberg contraptions on their bike’s rear ends, the conservative engineers from Sweden chose to keep using the tried-and-true dual shock treatment on their machines. While it may not have been as glamorous as the high tech linkage systems, it actually outperformed 90% of them. With a set of high dollar remote–reservoir Ohlins as standard equipment (this particular Husqvarna 430CR has had its stock Ohlins shocks removed), the Husky outperformed all but the revolutionary Suzuki Full-Floater in ’81. |

In the rear, the 430CR eschewed the home brew technique and instead went for high performance Swedish Ohlins components. By ’81, the motocross world was moving full speed ahead towards a single-shock future. All the manufacturers were debuting their own takes on the mono-shock concept with names like Full-Floater, Uni-Trac and Pro-Link. In the face of this inevitable march of technology, Husqvarna held steadfast to their belief in the traditional dual-shock design. While the newer linkage systems offered the advantage of rising rates and sophistication, the tried and true dual-shock was lighter and less expensive to produce. In this battle of old vs. new, only the incredible Suzuki Full-Floater was able to best the Husky’s proven Ohlins components. The 430’s rear end was plush in the rough and rock solid at speed. It exhibited none of the Jekyll and Hyde personality of the 1st generation Honda Pro-Link, but it lacked the amazing bump isolation of the Suzuki. When taken as a package, the Husky owned the honor of best overall suspension of ’81. It narrowly got beat by the Zook in the rear standings, but was far better in the fork wars.

|

|

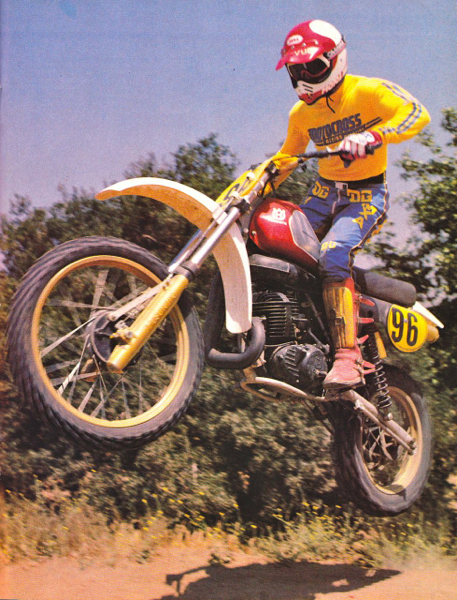

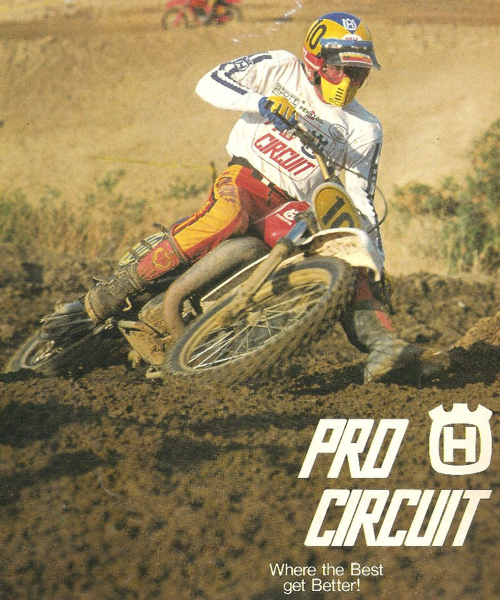

Long before Pro Circuit was a motocross powerhouse, they were a little known Husky dealer specializing in making Swedish iron go fast. As Husqvarna began to fall behind the competition in the early eighties, Mitch Payton was smart enough to take all of his eggs out of one basket and diversify his business to other brands as well. By the late eighties, Pro Circuit had become more than just another So-Cal go-fast tuner – they had become the hop-up shop to the stars. |

Handling was Husky’s claim to fame for much of the sixties and seventies, and the ’81 430 upheld this proud tradition. A rather long and tall bike, the 430CR loved to gobble up fast rough terrain by the mouthful. Amazingly, this excellent stability did not result in a lack of turning prowess. The big Hooska was sharp in the corners and tracked well at speed. Combined with its awesome suspension, the 430CR was an easy bike to go fast on. MXA called the ’81 430 the best handling Husky of all time, and that was no small complement.

|

When you look at the foot pegs of old bikes like these, it seems hard to believe we all thought these were good at the time. Compared to the gigantic floor boards on a modern machine, these spindly things look like they belong on a moped. |

Today the 1981 Husqvarna 430CR is largely a forgotten machine. It looses out in the glamor sweepstakes to the mighty Maico 490 that is still fawned over by classic bike enthusiasts to this day. In truth, the Husky lacked the technical achievement of the Suzuki, and the jaw dropping power of the Maico. What it did have however, was a tight handling chassis, excellent suspension and a do-it-all motor. It was not glamorous, but it did everything well and made going fast easy. With Husky’s downturn in the mid-eighties and eventual sell off, many people forget how good these bikes really were. In spite of all the hype that still surrounds the Maico 490 Mega 2, it was the Husky that was actually MXA’s pick for best overall open bike of ’81. In the years that have followed, the legend of the Maico has only grown in stature, while the-little-Swede-that-could has faded away. The onslaught of the Japanese would gobble up Maico, CZ, Husky, and nearly KTM by the end of the eighties. As it turned out, 1981 would prove to be the last stand of the old guard against the new. Thankfully at least, it was a grand stand indeed.