For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at what may be the best bike Suzuki has ever produced, the 1982 RM125-Z.

The late seventies and early eighties were the heydays of Suzuki 125 motocross machines. The RM was often the best bike in the class and they dominated national and international 125 motocross racing. Unquestionably, the best of these excellent bikes were the ’81-’82 RM125’s. With its revolutionary suspension and advanced, liquid-cooled power plant, it changed the face of small-bore racing. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The early eighties were a time of massive innovation in the motocross world. Every new model year would bring with it engineering breakthroughs and advances that would make the previous year’s offerings nearly obsolete. This technological arms race was at its hottest in the 125 class, where the Japanese were engaged in an all-out war for the disposable income of America’s youth. For the manufacturers, it was keep up, or get left behind, in the most competitive class in motocross.

For many years in the late seventies, 125 performance became synonymous with Suzuki’s little buzz bomb, the RM125. After being caught flatfooted by Honda’s incredible CR125 in the early part of the decade, Suzuki had come roaring back with some of the best eight-liters of the seventies. The Suzuki tiddlers became famous for their easy to use motors, plush suspension and solid handling. In the late seventies, Suzuki RM125s was the pick of the litter for pros and Joes alike.

While the ’81 and ’82 RM125s look nearly identical to the average observer, the ’82 model actually featured an all-new motor design. After years of using a semi case-reed induction on their 125’s, Suzuki unveiled an all-new reed-valve configuration on the RM125-Z. The new 124cc mill shared the same internal 54mm x 54mm dimensions as the ’81 “Power Reed” motor but used a completely new cylinder and case design. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

As the motocross world moved into the 1980s, the big buzz words were water-cooling and rising-rate suspension. The introduction of these new technologies was big news and signaled a huge change in motocross bike design. After being tested for years on Factory works bikes, the OEMs were finally ready to take the plunge into liquid-cooling. With the arrival of the ’82 models, all four of the major Japanese manufacturers offered water-pumpers on their 125 race bikes.

Feed by a 32mm Mikuni and flowing through a close-ratio six-speed transmission, the ‘82 RM125-Z mill offered a wide powerband, but very little “hit”. It was a great novice motor and could be effective in the right hands, but most riders preferred the burst of the ’81 mill. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Water cooling offered several benefits on a high-strung small-bore machine. Firstly, it allowed the engineers to deliver the bike in a higher state of tuning off the showroom floor. With liquid cooling, you could run more compression in the motor, more advance in the ignition, and tighter clearances internally. The more consistent motor temperatures made jetting the carburetor easier and reduced fear of overheating and detonation under heavy loads. All these factors allowed the motor to produce better quality power and maintain that power over a longer period of time. Its only real disadvantages were the added weight of the hardware and an increase in complexity.

For three years in the early eighties, Mark Barnett was the fastest 125 rider in America (or maybe even the World). On the amazing works RA125s Barnett dominated the field and wheelied away to three consecutive 125 National Motocross titles. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Much the same could be said of the switch to linkage equipped single-shock rear suspensions in the early eighties. The new rising-rate rear suspension designs offered better control and performance than most of their dual-shocked predecessors but were heavier and more complicated to service. In 1982, every manufacturer had their own unique take on this rising-rate concept. Kawasaki had been first to move to a linkage design with the unveiling of its original Uni-Trak in 1980 (although this first version lacked a rising rate curve due to patent issues). A year later in 1981, Honda and Suzuki joined in with linkage designs of their own. By 1982, all of the Big Four were offering some sort linkage in their rear suspension.

In 1982, all the manufacturers had very different ideas as to the best placement of the radiators for their liquid-cooling systems. Yamaha chose to mount theirs on the steering head, while Honda bolted their twin radiators in front of the gas tank. On the KX, Kawasaki decided to bolt one long radiator asymmetrically on the left side of the tank. For the RM, Suzuki hung one extra-large radiator in front of the frame, down low, below the tank (very similar to the 1997 Honda CR250R). The RM’s design offered both the lowest center of gravity and the largest cooling capacity. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The RM125-X used these new technologies to dominate small-bore racing in 1981. The all-new liquid-cooled mono-shock RM dominated the standings in the magazines and on the track. With Mark Barnett at the controls, a works version of the RM decimated the 125 field and delivered the brand its second 125 National Motocross title in a row. The stock RM125 was a huge advantage in 1981. It offered a fast motor, sharp handling, and by far the best suspension in the class. If winning was your priority, you could not do better than Suzuki’s RM125-X in 1981.

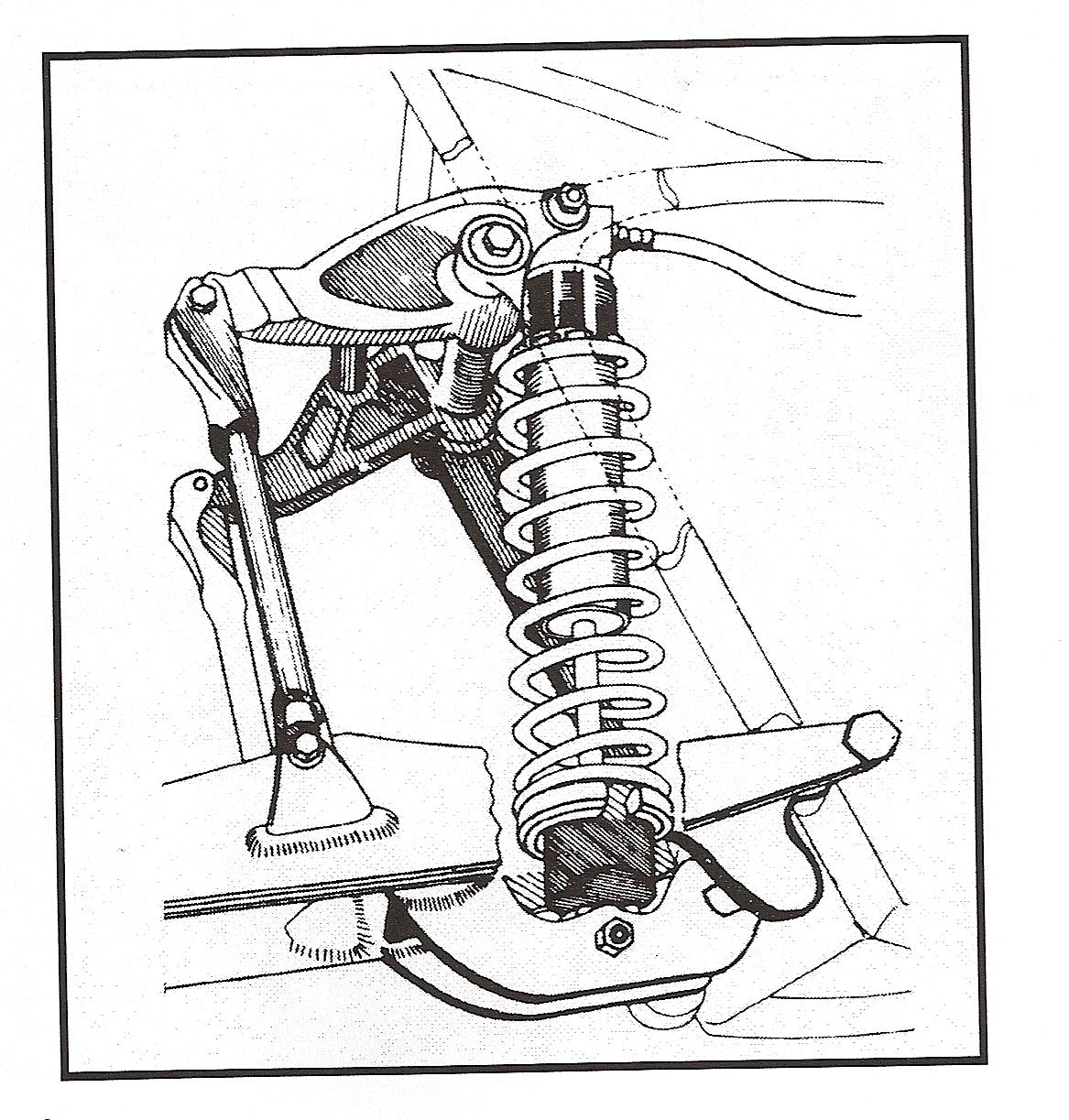

The secret to the RM’s incredible suspension performance was this complex set of pull rods and levers. Unlike a modern MX machine, the original Full-Floater actually articulated at both the top and the bottom, compressing the shock from both sides simultaneously. While it offered incredible terrain articulation and performance, its reign at the top of the suspension wars would only last five years. The combination of its complexity, cost, high center-of-gravity, and involvement in a patent-infringement lawsuit would lead to Suzuki retiring this original design in 1986. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In spite of offering the most popular machine in 1981, Suzuki decided to completely scrap their championship-winning power plant for 1982. The new motor maintained the liquid-cooling of 1981 but redesigned the intake to due away with the semi-case-reed intake the RMs had been using since the mid-seventies. The new motor employed the same 54mm x 54mm bore and stroke of the X model but redesigned the intake to flow directly through the cylinder. This was done in an effort to further broaden the power of the 123cc mill. The motor maintained the same 32mm Mikuni carburetor and electronic PEI ignition but added revised porting and a new exhaust to further increase power.

In the late seventies and early eighties, Suzuki was the bike to have in the 125 class. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Unfortunately for Suzuki, however, the new motor proved to be less popular than the 1981 version had been. Whereas the ’81 mill had featured a decent low-end, followed by an excellent mid-range, and solid top-end hook, the ’82 motor pumped out a smooth but uninspiring flow of power. The new Z motor pulled from a decently low in the rpm curve, but it lacked the old motor’s strong midrange rush. The ’82 motor offered a wide (for a 125) spread of easy-to-manage power, but very little verve. It felt slow compared to the ’81 RM and far less impressive than the hard-hitting ’82 Yamaha 125. With a skilled rider, it could still go very fast but most riders preferred the punchy ’81 to the smooth and slow-feeling ’82.

At first glance, the ’82 RM125-Z appeared to be merely an ’81 RM125-X with Bold New Graphics. Under the skin, however, Suzuki made many refinements, both small and large that added up to a very different motorcycle. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The real star of the ’82 RM125-Z was, of course, its incredible rear suspension. The original Suzuki Full Floater was an amazing piece of engineering in 1981, and would seem pretty advanced even today. The heart of the original Full Floater was a set of articulating linkages that compressed the shock at both the top and the bottom. This was the basis for the system’s name as the shock was said to “full floating” without any hard mounting points to the frame.

For ’82, Suzuki dialed up some minor refinements to their class-leading suspension. An all-new shock was installed the Suzuki claimed was a replica of the one used by Barnett in ’81. The new shock was smaller and lighter than in 1981 and promised to offer better rebound control and smoother overall performance.

The star of any Suzuki from 1981 through 1985, was its Full Floater rear suspension. Refinements made to the second generation of the Floater in ’82 added up to improved performance but reduced reliability. It still offered the best performance in the class in 1982, but the new shock proved prone to failures. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In terms of performance, the new shock offered some advantages and some drawbacks over the ’81 design. On the X model, the only real weakness had been a tendency to kick under braking. The new lightweight shock rectified this problem, with a smoother action and improved performance on braking bumps. Just like its ’81 counterpart, the Z model Floater gobbled up whoops and bumps like Homer Simpson attacking a box of doughnuts. Big or small, peaked or smooth, it made no difference to the incredible Full Floater. As long as you kept the throttle on, nothing upset Suzuki’s magic shock. On the track, its only downfall turned out to be reliability, which proved sub-par. The new smaller shock suffered from failures throughout the year and proved far less reliable than the beefier X model shock had been.

In the front, the ’82 RM125-Z employed a set of 38mm air-adjustable Kayaba forks to punch out 11.2” of plush travel. They absorbed small and medium impacts easily but were a little soft for faster riders. The RM’s single-leading-shoe drum brakes were considered very average in ’82 and lagged far behind the impressive front disc on the KX125. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In the fork department, the Z model’s 38mm Kayaba conventional forks offered 11.2” of plush travel. They were praised at the time for their smooth action and comfortable ride. By modern standards, they were incredibly soft, but in ’82, they were considered excellent performers. Faster riders needed stiffer springs, but overall they were rated very highly for most riders. When combined with the awesome rear shock, the RM125-Z offered the best suspension package in the 1982 125 class.

The infamous “duckbilled platypus” front fender made its debut on the ’82 RM line. While not quite as bizarre as the fenders on the ’79 RMs, this new design certainly earned its place in the pantheon of odd Suzuki design choices. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Suzuki did not stop at the shock when looking for weight saving on the RM125-Z, and those efforts paid big dividends in the handling of the machine. Nearly every part of the bike went on a diet in ’82. Every piece of plastic except the tank was shaved down to be as light as possible. Suzuki milled and hollowed out every bolt and part they could think of to shave an ounce or two. The result was a featherweight 192-pound tiddler. This made the RM the lightest bike in the class, and actually lighter than most of its air-cooled predecessors. On the track, the RM was an absolute joy to ride and acted like an extension of the rider’s will. It carved up corners and blasted down straights with equal ease. Its smooth, broad power worked together with the light weight, supple suspension, and excellent frame geometry to make the RM by far the easiest bike to go fast on in ’82.

A few modern features that made there debut on the ’82 RMs, were a “side-pull” throttle (this RM which was in the Greg Primm collection RM appears to have had the original throttle assembly replaced with one from an older RM), split perches with “dog-leg” levers, and a folding shift lever. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In the detailing department, the ’82 RM added many features that we now take for granted. Things like dog-leg levers, split perches, and a side pull throttle all made their debut on the RM125-Z. Even the addition of a folding shift lever was big news in ’82. While these were welcome additions, the RM continued to offer some of the most lackluster detailing in the class. Piston and ring wear was excessive and the bike got tired very quickly if ridden hard. Shock life, bolt quality, and component durability were all poor as well. The airbox also continued to be an utter nightmare to service requiring an assortment of different tools to access the dual filter elements.

Pad life and overall performance on the RM’s brakes were merely adequate in 1982. All three of its competitors offered superior performance with the KX’s disc outclassing all the others by a wide margin. While bike tended to feel tired pretty quickly, it actually proved very reliable for the most part. Keep fresh rings it and it would reward you with many hours of happy roosting.

The 1882 RM125-Z would prove to be Suzuki’s last shootout winning 125 for a decade. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In ’81 the RM125-X took the world by storm with its powerful motor and incredible suspension. It won all the shootouts and nothing else was even close. For ’82, all-new machines from Yamaha, Honda, and Kawasaki offered much more competition for the class-leading RM. The YZ and KX both offered harder-hitting motors than the mellow RM, and in the case of the KX better brakes as well. In the end, the RM125-Z claimed the 125 class win by virtue of its solid overall package. It was not the fastest bike, but it made going fast easy for the rider. For Suzuki, this would be the zenith of their powers in the 1980s. After the RM125-Z, Suzuki would fall behind in the relentless march of progress that defined 1980s motocross. Honda and Kawasaki would take over the leading role in the 125 class and leave the RM125 in their wake. For Suzuki, it would be a full decade before they would once again stand atop the 125 class standings.