Unrestrained expectation-we have all experienced it. It is that palatable anticipation that comes from wanting something to be great so badly, we can nearly taste it.

Unrestrained expectation-we have all experienced it. It is that palatable anticipation that comes from wanting something to be great so badly, we can nearly taste it.

It is a state of mind, not based on fact, but on feeling. It often has no bearing on reality, and seldom does it resolve itself in a satisfying manner. It does not matter if it is the latest Apple iWhatever (thinner, magical, smaller, amazing, revolutionary, game changing, blah, blah, blah…) or a humongous summer blockbuster (I’m looking at you, Star Wars Episode I The Phantom Stinkage); wanting it to be good, and expecting it to be great, are seldom good barometers of something’s eventual success.

In our sport, this excessive enthusiasm (also referred to as “spraying with pump” in certain circles) is most often associated with preseason predictions and new model introductions. Before the start of the season, every fan wants their favorite rider to be the one to spray all the champagne, and every OEM PR guy wants you to believe their brand of bike is the greatest thing since sliced bread (which is pretty awesome BTW). Unfortunately, the majority of the time, these expectations go unfulfilled. In our sport, there can only be one winner, and 90% of the time, that one guy is hogging all the wins and stealing all the glory. More often than not, the reality just can’t measure up to the hype.

This leads me to the subject of our latest PulpMX.com retrospective. I thought it would be interesting to look back at the bikes that have best exemplified this dichotomy between expectation and reality. These are the bikes that had the “Hype Machine” cranked into high gear, only to fall crashing back to Earth, once the buying public realized the gruesome truth. To be clear, this is not a list of the worst bikes ever (I already did that, and you can read it HERE), but rather a list of the biggest disappointments in relation to expectation. Some were collateral damage from their own PR departments, others were casualties of the media, and some were the unfortunate victims of their own progenitor’s greatness. In every case, they were a colossal disappointment. Here is my list of the eight biggest MX bike bombs of all-time, with a few personal sob stories thrown in for good measure.

|

|

#8 The 2010 Yamaha YZ450F |

Ok, so you just knew it had to be here. My “affection” for the current generation YZ450F is well publicized, and in that opinion, I am not alone. First of all, I want to be clear that I am not a Yamaha hater. I have owned over a dozen Y-Zeds over the years. As a rule, I love the blue bikes. They are extremely well put together and as reliable as a stone axe. That being said, however, it is hard to ignore the massive black eye the current YZF has been for the company that basically invented the modern four-stroke.

This is a company that had a five-year lead on their closest competitor and nearly a decade lead on Kawasaki. Think about it, as recently as 2009, Yamaha had won three straight US 450 titles (2008, 2009 Supercross and 2007 450 Outdoor), plus countless GP victories in Europe. The YZF was a solid, if not flashy machine and popular with riders and race teams alike. Fast-forward four years, and you have a smoking ruin where Yamaha’s race effort used to be. They have become the punching bag of the sport, with a string of very high profile missteps by half a dozen Yamaha supported teams. The JGR situation is so bad, that Coy Gibbs is starting to look like Wile E. Coyote at this point, with fans just waiting for the next Acme anvil to fall on him. When top riders will not even consider your team because of the brand you ride, you know you have a problem.

When Yamaha was preparing to introduce the 2010 bike, it was handled with a top-secret info embargo worthy of Apple. No one was allowed to leak pictures or data about the new machine and speculation ran rampant about some crazy and radically new design from the Piano Company. Some of this probably had to do with concerns over the bad economy and a glut of left over 2009 bikes still in dealer showrooms, but regardless of the reason, anticipation for the “revolutionary” new YZF was fanned to a fevered pitch. Once the actual bike was unveiled, however, things quickly went south.

To many people’s minds, the new YZF answered a lot of questions that no one had been asking. Even worse, Cannondale had already attempted many of the bizarre design choices a decade earlier, to disastrous results. The new YZF was big and bulky, with a heavy feel. Even worse, it sounded weird, looked funky and handled strangely. It was the Bizzaro version of a 450 motocross bike. It was powerful and reliable, but not quite right.

Four years later, the YZF is still the most polarizing machine in motocross. It was not the game changer Yamaha promised in 2010, and in fact, has turned out to be an albatross around their neck. With a greatly revised (but apparently still back-asswards) 2014 YZF on the horizon, it is too early to tell if the 2010-2013 YZ450F will prove to just be another manufacturer misstep, or the machine that crippled a giant. Here’s hoping that Big Blue can get its groove back.

|

|

#7 The 2009 Honda CRF450R |

For anyone who thinks I am a Yamaha hater, just take one look at all the red bikes on this list. Some of that is of course due to the increased expectation that comes with being the biggest and highest profile of all the manufacturers. In truth, KTM went the entire decade of the eighties without building a single decent motocross bike. Every bike was a half-baked effort, with crappy suspension and a chassis set up for road racing. The difference here is, no one expected them to build anything decent at the time. They were an also ran in the motocross world and acted like it. When Big Red rolls out a turd, however, people take notice. It is all about expectation.

This leads me to the number seven bike on our list, the 2009 Honda CRF450R. Similarly to the 2010 YZF, the ’09 Honda succeeded one of the most successful machines in motocross. Unlike the YZF, however, the CRF’s success did not come from National titles. Instead, it was rooted in shootout victories and consumer good will. The 2005 through 2008 CRF450R’s were some of the most universally loved machines Honda has ever produced (some still hold the 2008 450R as the best motocross bike ever built). It was brutally fast, flawlessly built and loved by all.

With so much to live up to, there was a lot riding on the big redesign Honda had scheduled for 2009. This, however, was Honda, and they had been cranking out one home run after another since the introduction of their game changing answer to the YZ426F in 2002. Each bike had built on the success of the last, and by 2008, Big Red had this down to a science.

One look at the all-new (and drop dead gorgeous) 2009 CRF told you everything you needed to know about the new rocket from Honda. It looked like a two-wheeled Ferrari 599 and screamed performance. Its bodywork was shrink-wrapped over its svelte new frame and mated to an all-new fuel injected power plant. Just like its Italian counterpart, the new CRF was pure sex on wheels.

Unfortunately, motocross is not a fashion show (although many people might argue that point), and more than good looks are needed to capture the checkered flag in the most grueling motorsport in the world. Once you got past its matinee-idol good looks, the new CRF was a bit of a mess. For starters, it was slow. That new fuel injected motor ran like it had a sock in the airbox past the midrange and was no match for the old-fashioned carbureted one. Plus, the chassis was set up all wrong, with a jacked up rear end and a hangdog front. This permanent “stink-bug” stance was not conducive to rider confidence. While impressively light (especially in view of its competition’s porky proportions), its cramped ergos were not loved by everyone.

In short, the 2009 CRF looked great, but was slow and handled funky. It was a supermodel, with the IQ of a rice cake. While Honda has improved the CRF in subsequent years, it still has not been able to recapture the magic they had in 2008 (including with their once more controversial 2013 CRF). 2009 was a disappointment for Honda, but as this list will show, it was far from their biggest blunder.

|

|

#6 The 1998 Honda CR125R |

This bike is significant, as it signals the true end of a motocross dynasty. From 1983 through 1995, Honda owned a virtual stranglehold on the 125 class, with rocket fast motors that were usually quicker than the other brand’s modified machines. Then in 1996, Yamaha introduced their radically reinvented YZ125 and snatched the crown of 125 powerhouse away from Honda. The CR125 still held the honor of producing the most top end power, but it lost out everywhere else to the brawny Yammie.

For 1998, Honda was set to fire back with an all new CR125R. It was going to receive Honda’s radical new twin-spar alloy chassis and reportedly beef up the red tiddler’s previously lackluster low-to-mid power. Before we go any farther, I want to reset people’s minds a bit to 1997. History, has of course taught us that the first gen Honda chassis was a colossal misstep, but in ’97 this was far from the general opinion. At the time, most people still thought the new Honda looked like some space age Works bike from ten years into the future and consumers were beating down Honda’s doors to get their hands on the most radical machine in motocross. The switch to the new chassis was looked at as a good thing and highly anticipated.

The one thing people did not expect out of the ’98 CR125R was a dog slow motor. In ’97, even the riders who took umbrage with the new CR250R’s ridged chassis had no complaints about the power of its motor. It may have rode like a 1969 Jeep Wagoneer, but it rode like a very fast 1969 Jeep Wagoneer. Unfortunately, there was no such luck with the all-new eighth-liter version. It got the absurd rigidity and numb feel of the ’97 250, and combined it with a motor that could not outrun an 80.

Where the ’90-’97 CR125R’s had been blazing fast top-end screamers, the ’98 version was mid-range only and slow. It had a little burp of power midway through the curve and nothing anywhere else. Low end power was an endless chasm of bog and top end was little more than noise and vibration as the little Honda struggled to make it to the rev limiter. Even worse, the bike was slow to build rpm’s and lethargic for a high strung 125. Coming out of corners, it required several stabs of the clutch to get the little motor percolating and a quick left foot to keep it in its microscopic sweet spot.

Instead of taking back the crown of top 125, the little Honda became the whipping boy of the 125 class. Its anemic performance and unforgiving chassis cost it in the standings and on the track. The ’98 CR125 was a massive disappointment for Honda fans and the end of one of the greatest runs in the sport’s history.

|

|

#5 The 1988 Honda CR250RJ |

For those of you under the age of forty, or like Tits Legendary, uninterested in anything that happened in Moto before 2005, it is hard to understate how incredibly different the motocross landscape was in 1987. Unlike today, where the only real difference between the bikes is the color of their plastic and a few odds and ends (except for KTM, who continues to go their own way Kenny Watson style), in 1987, there was a massive difference between the machines. It was a real case of the haves and the have-nots, with the haves consisting of Honda and the have-nots consisting of everyone else.

After a rough start in 1981, Honda had used their new hire of Roger DeCoster to completely turn around their motocross program. Their bikes went from the back of the pack to the front of the line, nearly over night. By ’82 they were turning heads, and by ’83 they were collecting shootout victories. Honda’s were the bikes to be on; their works machines were the baddest in the land and their stock machines were the best looking, and often the best performing.

No year better exemplified this Honda domination than 1987. In ’87, the Big Red Machine took every shootout victory in an absolute rout. These were not the shootouts you see today, where the writers go on about how it comes down to personal preference, dealer support and blah, blah, blah. These were the kind of shootout victories where the Honda is incredibly good and everything else is pretty much a pile of crap. The CR’s this year were like RC outdoors in 2002-on a whole different level.

Because of this domination (and certainly to some extent, because of the success of their race team), many people think of the eighties as Honda’s decade. While there is some merit to this thinking, not every machine they made in the eighties was a superstar. For every incredible ’83 CR480R, there was a grusome ’84 CR500R thrown in for good measure. Early on, this was expected, but after the complete shellacking they gave the field in ’86 and ’87, many people started to think they could do no wrong. Unfortunately, some of those people apparently also worked at Honda.

For ‘88, Honda retired their world beating ’87 CR250R and replaced it with one of the most gorgeous pieces of moto art ever to set wheels to dirt, the 1988 CR250RJ. The new bike was blood red, low slung and all business. The monochromatic look was a huge departure from the bright orange and blue of the previous five years and the “low boy” layout was pure works. As if to drive home the point that this was a very special CR, Honda even christened the new bike the CR250 “RJ”, as if this was some kind of Rick Johnson replica. Once again, Honda looked to have a home run on its hands.

Unfortunately, once riders actually started getting their hands on the new CR, it became apparent something had gone terribly wrong. Where the ’87 model had been an absolute rocket, the new RJ was lethargic and slow. It produced a very linear delivery that lacked hit and was boring to ride. After the previous five years of fast and solid CR250R motors, this new mellow CR was quite a shock.

In addition to screwing up the motor, Honda completely shattered their glorious two year run of suspension dominance with the new CR. The amazing cartridge forks that had ruled motocross the previous two years were set up all wrong and no longer the star of the field. The new “delta link” rear suspension was harsh over anything smaller than a Supercross whoop and punishing to ride. While the new low boy layout was a huge hit, the rest of the bike was a disappointment.

After the debut of the CR250RJ, Honda would never again pull together all the ingredients in a 250 that made the ’86 and 87 CR’s such world beaters. In ’89 they would bring back the horsepower, but mate it to atrocious suspension. By the time they got the suspension right in 2002, the horsepower had once again gone on hiatus. For Honda, 1987 was that magic year where they did everything right and everyone else did everything wrong. A year later, the shoe was on the other foot and it was Honda taking its lumps. The 1988 CR250R had the unenviable task of following up one of the greatest motocross bikes ever built and it suffered for the comparison. Because of this, it stands as the fifth biggest disappointment on our list.

|

|

|

|

|

#4 The 2004 Kawasaki KX250F/ Suzuki RM-Z 250 |

Ah, the ill-fated Kawasaki/Suzuki alliance. It was a noble experiment; born out of market pressure and a desire to better compete with motorcycle juggernaut Honda. In 2003, this seemed like a pretty good idea. The two could pool their resources, sharing models and leveraging each other’s strengths. While early on, we got some yellow Kawasaki Prairie’s and a few green DR-Z’s, the true fruit of this marriage of convenience was to be the first real competition for the revolutionary Yamaha YZ250F. The new bike would be a true joint venture, with Suzuki designing the power plant and Kawasaki building the chassis. Kawasaki would handle the final assembly, and both manufacturers would sell the bikes, with minor plastic changes as the only difference between the two.

While I’m sure Kawasaki and Suzuki dealers were happy to have 250F’s on the showroom floors in 2004, it is pretty clear now that it would have been better if they had waited another year or two to roll them out. Whether because of budgetary constraints, or due to the logistical issues of the joint venture, the first generation KXF/RM-Z turned out to be a half-baked effort. Even though it had been a full seven years since the debut of Yamaha’s original YZ400F, the new Kawasuki looked to be a rushed project.

In terms of outright performance, the bike was not a total disaster. It had a pleasant low-to mid powerband that made the bike easy to ride and relatively competitive. Suspension was decent and handling was typical of Kawasaki’s of the time, with modest turning precision and good stability. Where the package fell apart, however, was in the details.

For starters, the bike’s cooling system was woefully undersized. Four-strokes run hot, and 14,000 rpm four-strokes run really hot. This, combined with the alliance’s decision to go with a very small oil capacity and no remote oil tank, spelled doom for unsuspecting Kawasuki owners. The green and yellow 250F’s overheated at the slightest provocation and loved to puke all their precious coolant out if left to idle for more than a few seconds. In addition to overheating, the little four bangers guzzled oil at an alarming rate. Considering there was less than a quart of the precious fluid sitting between you and a catastrophically expensive failure, this was no small concern. This was also in an era where anyone familiar with a four-stroke, was most likely used to a completely maintenance free play bike or bullet proof YZF, so filling the oil tank as rapidly as the fuel tank was not paramount in most rider’s minds.

Along with the overheating and oil consumption issues, there were problems with the cam buckets, valves and valve seats. If none of those things failed then you still had a good chance of the trans letting go. In truth, if the it had been the RM-Z and not the YZF that had been the first bike to really try and break the two-stroke glass ceiling, I’m not sure the revolution would not have been stillborn. The alliance bikes typified everything that scared people away from complicated thumpers in the first place. They were more expensive to buy, harder to maintain (changing the stupid oil required draining the entire cooling system), complicated to fix and fragile to own.

After a mere three years and a great deal of bickering and finger pointing, Kawasaki and Suzuki would agree to disagree and file for divorce. Interestingly, the 2004-2005 (Kawasaki got an all-new bike in ’06, but Suzuki was stuck with the steel framed turd one more year) KXF/RM-Z would be the only significant child of this interesting pairing. It was an idea with a lot of promise, but an unsatisfactory outcome for all involved.

|

|

#3 The 1997 Honda CR250R |

In a sport like motocross, new trumps reason every time. If it is new and shiny, it is going to steal the limelight ten times out of ten. More often than not, it is that three-year-old design with all the bugs worked out that you should buy, but it is that sexy new model that you want to buy. In 1996, Honda unveiled the newest and sexiest motocross machine of all time (or so it seemed at the time); the groundbreaking 1997 alloy framed CR250R.

When pictures of this baby started making their way around the pits in early ’96, the buzzo-meter was pegged at 110%. The Japanese had been toying with alloy motocross chassis’ for a decade by this point, but no one had had the gonads to pull the trigger and actually put one into production. Now Honda was set to take the plunge, and boy did that bike look trick.

The new CR chassis borrowed liberally from the road racing world with its exotic twin-spar perimeter framework and alloy construction. The bodywork was just as space-age as the frame, curving and flowing front to back. One look at the new bike immediately made the outgoing CR look like some kind of antique. Once again, Honda’s endless resources and unparalleled racing success had delivered a bike that would surely decimate the motocross field.

Dud:

1. A bomb, shell, or explosive round that fails to detonate.

2. Informal One that is disappointingly ineffective or unsuccessful.

3. Example The 1997 Honda CR250R

Initially, testers riding the new recycling friendly CR referred to its ingot solid chassis as “Supercross ready” and “pro oriented”. After the ether wore off, however, those descriptions morphed into “absurdly harsh” and “punishingly ridged”. The new bike looked incredible, but beat riders to death. It transmitted every pebble right to your hands, felt vague in the corners and thudded through the whoops. That awesome 249cc powerhouse was still in place, but the rest of the bike was an exercise in brutality.

In terms of sales, the new CR was a massive success. Riders could not snap them up fast enough and dealers could not keep them in the showrooms. In terms of on the track success, however, the bike was a colossal disappointment. That the atrocious performance of the bike played a role in Jeremy McGrath’s last second defection to Suzuki, there can be no doubt. With the new bike, Honda lost its first 250 Supercross title in nearly a decade and failed to win a single main event. The ’97 CR was another bike that could have been great if they had waited a little bit longer to put it into production. It was fast, and it was cool, but most importantly, it was just plain bad.

|

|

#2 The 2000 Cannondale MX400 |

In first and second, we have two colossal disappointments that came up way short of expectations. I went back and forth for quite a while on which one deserved the dubious honor of number one here. In the end, I decided the Honda deserved to take the crown. My reasoning was thus: I think we all wanted the Cannondale to be great, but I think very few people actually thought it would be a world beater. The project was fraught with problems and delays from the very beginning. There were major technical hurdles and supply problems at every turn and at times it looked like the bike might never get built. Plus, once they actually started trying to race them, they kept blowing up (this was a major PR gaffe by Cannondale. NEVER air your dirty laundry) very publicly. By the time they actually started to roll off the assembly line, only the most optimistic amongst us had any real confidence the bike was going to be great. There was a huge buzz and anticipation initially, but by the time the bike became a reality, that had been trampled down to a murmur.

I still think the MX400 ranks as the second biggest disappointment, however, due to all the ridiculous hype that preceded its introduction. It got so out of control at one point, that Dirt Rider Magazine named it the “Bike of the Year” a full two years before the first machine rolled of the assembly line. Going into the project there was a great deal of optimism. Cannondale was a huge name in mountain biking and seemed the perfect candidate to use their extensive knowledge of alloy frame design to develop a truly competitive American motorcycle. History would of course show that the cycling giant bit off more than they could chew with the MX400, and try as they might, it did not work.

Once the MX400 hit the track, the press and the public were underwhelmed. The price was sky high, the performance was mediocre, and the reliability was nonexistent. Every test bike given to the magazines blew up in spectacular fashion. In short, things didn’t go particularly well. The MX400 does hold the dubious honor of single handedly sinking the company that produced it, so that is something. In the end, there is little doubt the MX400 stands as one of the biggest disappointments in the history of motocross. That said, I still feel it must line up behind the massive POS that tops out list.

|

|

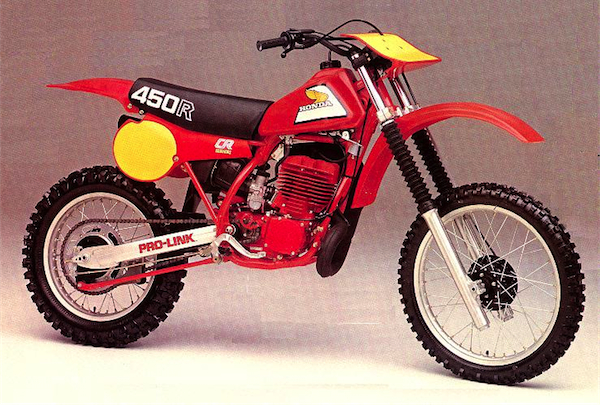

#1 The 1981 Honda CR450R Elsinore |

In first, we have a bike that over the years has graced more worst bike lists than anything short of a TM400 Cyclone. No less that Roger DeCoster has been quoted as saying this was the worst bike he had ever ridden. When you consider The Man has probably ridden every significant motocross machine made in the last forty five years, that is saying something. Put simply, the 1981 Honda CR450R stands alone as the most disappointing motocross bike ever built.

The 1981 CR450R was a bike led up to by unprecedented anticipation. Prior to 1981, Honda had not offered a production Open bike to the buying public. This in spite of racing 500’s in the GP’s and US Nationals for half a decade. From the mid-seventies on, Honda RC450’s we some of the trickest and most successful bikes on the track. Riders like Lackey, Pomeroy, DeCoster and Malherbe won on the track, and fueled customer desire for a purpose built Honda 500 racer.

As 1980 approached, it became clear that Honda was indeed going to introduce a production Open Class machine. At this time the 500’s were still the most prestigious class in motocross and this caused quite a lot of buzz. The new bike would be completely new from the ground up and feature the trick “Pro-Link” single shock rear suspension right off of Malherbe’s 500cc World Title winning RC500. The bike would feature an all-new frame, massive 43mm forks and swoopy new bodywork. Literally, a full six years in the making, the CR450R had a lot to live up to in ’81.

Unfortunately, as we have seen again and again on this list, sweet looks and a bulging spec sheet do not a winner make. Despite all its works technology and the massive might of Honda Motor Corporation, the new CR450R was epically bad by any measure. It was grossly overweight, tipping the scales at close to 260 pounds (porky by any standards). The new fire-engine red motor was small for an Open bike and ran like a massively overpowered 125. Low-end torque was nearly non-existent with all the power delivered in a single massive burst. Bog, hit, wheelie, repeat best described the riding experience.

Honda also saw fit to saddle the 450 with a hopelessly spaced four-speed gearbox that only exacerbated its narrow power spread. The gaps between gears were a mile wide, resulting in the need to slip the clutch to get the pipey 450 back on the powerband. This, of course, would smoke the hopelessly overtaxed clutch in a matter of minutes. Once hot, the clutch would buck and chatter before giving up the ghost completely. Awesome, this motor was not.

In addition to its pathetic power plant, the CR’s radical new rear suspension worked no better than the dual shocks it replaced, while adding 10 pounds of unwanted weight. It was far too soft initially, then harsh and stiff in the last third of the travel. In addition to performing poorly, shock fade and failures were common. The forks were even worse, with Dirt Bike comparing them to a set of pogo sticks with worn bushings. Worst of all, was the reliability. In addition to the aforementioned shock; frames broke, swingarms cracked and transmission gears sheared, all with alarming regularity. It was fat, absurdly hard to ride, shook its head like a wet dog and unreliable. The bike the World had waited nearly an entire decade for, was an epic letdown and an epic fail.