For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the story of the machine that kickstarted the Japanese motocross revolution, the 1973 Honda CR250M Elsinore.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the story of the machine that kickstarted the Japanese motocross revolution, the 1973 Honda CR250M Elsinore.

|

|

In 1973, Honda introduced a $1145 machine that not only undercut the competition in price, but out-classed them in quality and performance. Even more incredibly, it was a machine that nearly never existed. If not for the passion of a few enterprising engineers, the face of seventies motocross would have looked very different indeed. |

In 1972, the Motocross landscape was very different than it is today. At that time, most riders rode machines from Germany, Sweden or Czechoslovakia. Motocross had started in Europe, and the Old World powers still owned the lion’s share of the market. Maico’s, Husky’s and CZ’s were the mount of choice for riders who took things seriously. In 1972, the Japanese were little more than a sideshow curiosity.

|

|

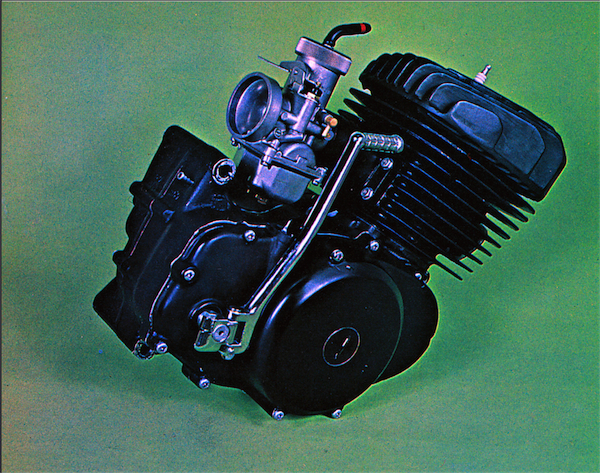

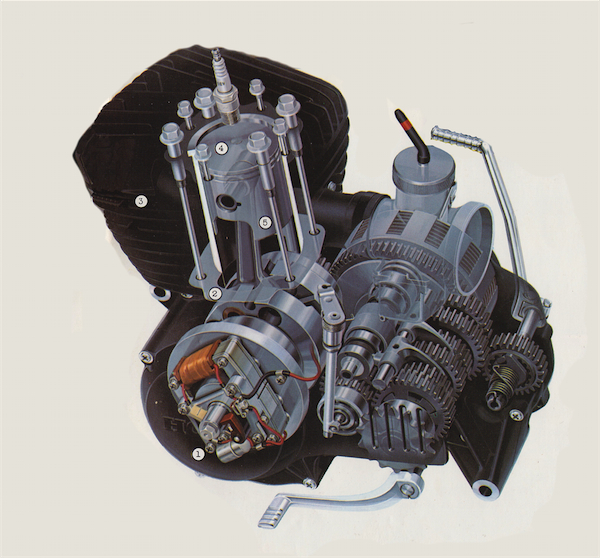

In 1973, the power plant on the Elsinore was remarkable not just for its power, but also for its everyday livability . Cranking out just shy of 26 horsepower from its 248cc’s, it offered a solid spread of ponies from bottom to top. Best of all (in an era were breakdowns were virtually expected), it started, carbureted and ran as reliably as any of Honda’s street machines. |

|

|

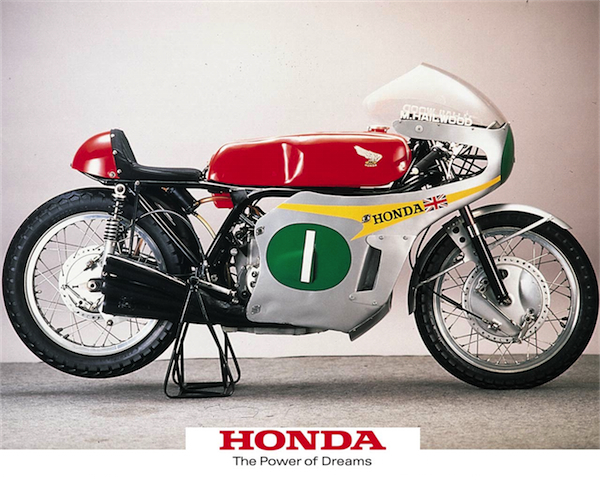

Screamer: Although Honda had shied away from two-strokes and motocross prior to the Elsinore, they had not been adverse to racing. In the sixties, Honda built some of the most advanced bikes on the Grand Prix road race circuit. This 1966 RC166 Factory racer used a 250cc six-cylinder power plant capable of turning nearly 20,000 rpm! |

Although Japanese upstart Suzuki had enjoyed a great deal of success at the Factory racing level (winning several World Motocross titles in the early seventies), very little of that Japanese technology had made its way back to the showrooms. In advertisements, Suzuki billed their TM’s as near replicas of the championship winning works machines of Joel Robert and Roger DeCoster, while in actuality; they were nothing of the kind. In these early days of Japanese involvement in the sport, it was with good reason that savvy consumers stayed away from the Nipponese machines. By any measure, Japanese bikes from this era were just not very good and in some cases, downright terrible. Bikes like the Yamaha SC500, Suzuki TM400 Cyclone and Kawasaki 350 Bighorn (a machine Dirt Bike famously coined, the “Pig Horn”) live on to this day as icons of early Japanese futility. In 1972, if you rode a Japanese, it meant you were cheap, stupid, or most likely, both.

|

|

Pocket rocket: Here is a picture of just how tiny the piston and rod were in the incredibly trick RC166. |

In the spring of 1972, all that changed with the introduction of one machine – the Honda CR250M Elsinore. The Elsinore was a revolution at the time and Honda’s first production two-stroke. Prior to ’72, Honda had focused its production solely on four-stroke motorcycles. They had built a huge international following producing inexpensive, reliable and fun street and off-road motorcycles. Honda had become the “anti-Harley” and the slogan “You meet the nicest people on a Honda” was more than just so much Madison Avenue nonsense. People who would not want to get within 1000 feet of a big chopper, were more than willing to swing a leg over a Honda Dream or Mini Trail 70. Hondas were quiet, Hondas were cute, and Hondas most certainly did not belch out any of that nasty, smelly, blue smoke from the the tail pipe. In fact, Honda Motor Corp. was so against the two–stroke motor, that the company’s President Soichiro Honda once famously proclaimed, “Honda will never build a two-stroke motorcycle!” At Honda, the two-stroke was persona non grata.

|

|

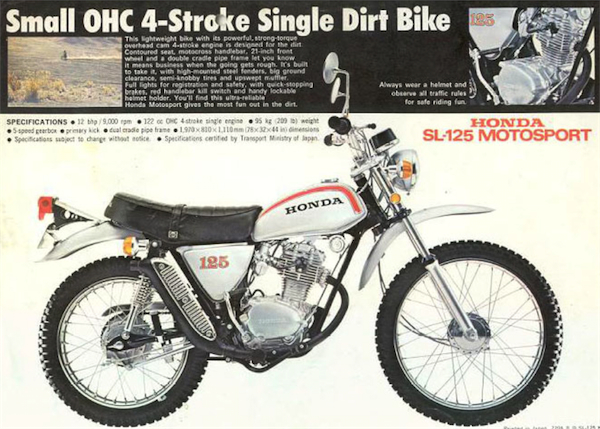

Back to the drawing board: With Honda Motors Corp. officially choosing to ignore the exploding popularity of motocross in Japan, it fell upon some enterprising young engineers within the company to try and build a Honda motocross racer on their own. Calling themselves “The Association to Study the Motorcycle” and using a Honda SL125 Enduro as a starting point, the engineers tried to turn the mild-mannered SL trail bike into a highly stressed racer. Once the team actually hit the track, however, it became abundantly clear that no four-stroke play bike was going to cut it against the fire-breathing two-stroke works machines of the competition. |

In the late fifties, Honda had become seriously involved in GP road racing, but had stuck to their guns by only building four-stroke race bikes. In spite of being valve and cam machines, they had been some of the most advanced bikes of the era. Incredible exotica like their 19,000-rpm, six-cylinder 250cc RC166 road racer showed the World the manufacturer’s incredible engineering know-how and capacity for innovation. Racing was a passion at Honda, and Soichiro spared no expense in recruiting the best engineers from every corners of the globe to help propel Honda to the top. After reaching their goals in road racing, Honda pulled out of the Grand Prix’s in 1967, at precisely the same time a new sport was taking hold in the land of the rising sun.

|

|

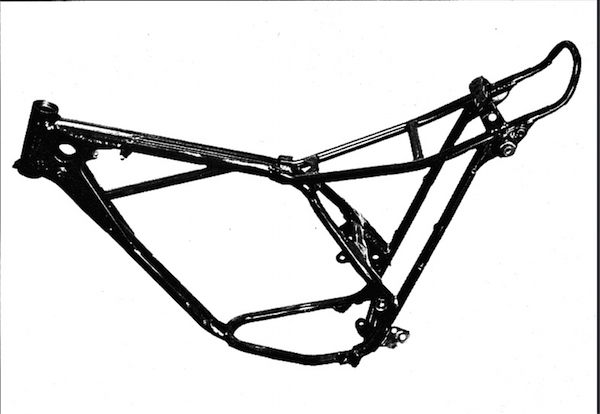

At the time of the Elsinore’s release in March of 1973, it was the lightest production 250 motocrosser in the world at 215 pounds ready to race. This helped in all phases of its performance, from acceleration to handling. In an era where most production machines were heavy, fragile and finished like farm equipment, the impeccably detailed Elsinore was a revelation. |

|

|

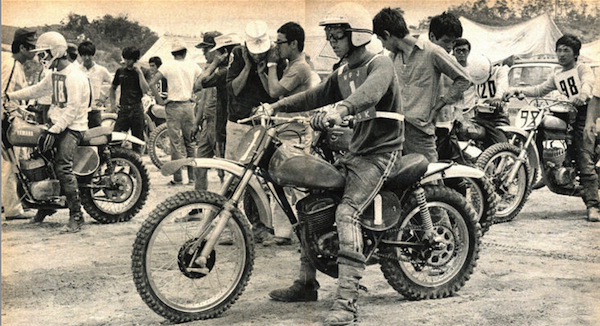

After the failure of the SL125 experiment, The Association to Study the Motorcycle, got the green light from a few people in the R&D department to do a little experimentation at building a two-stroke machine. The project (codenamed 335), was strictly under the table and off the radar of the bosses at Honda. Within a few months, the team had cobbled together a motorcycle to test (pictured above) and Honda was on it way to being a two-stroke manufacturer. |

While Motocross (originally known as scrambles) races had been taking place for nearly half a century by the sixties, the sport had not really taken off outside of Europe. Then in the mid-sixties, motocross began to extend its reach. Countries like America and Japan began to take notice and by 1967, Japan was holding its first official motocross series, the “All Japan Motocross Championship”. While Suzuki was fast to jump into the new sport with both feet, Honda at first resisted the temptation to join its competitors in the rough and tumble world of motocross. After all, Honda built bikes for nice people, not dirty old motocross racers. With Honda Motors Corp. officially ignoring the emerging sport of motocross in Japan, a small group of engineers within their R&D department took it upon themselves to begin work on a project to explore the possibility of racing one of their four-stroke machines in the Japanese Motocross Nationals.

|

|

At 62 pounds, the 70 x 64.4mm Elsinore mill was no lightweight, but its fit and finish were impeccable (particularly for a first effort). Magnesium cases, straight-cut gears, reliable electrics and excellent carburation were all key selling points on the new CR. Its 34mm Keihin PW34 carburetor was an all-new design and built specifically for the CR250M. It featured novel ideas like a splash baffle for the main jet to prevent bogging in the rough and an actual choke to aid cold starting (The Bing carburetors most common at the time lacked this convenient starting feature). |

|

|

Originally, Honda’s first official two-stroke was supposed to be an oil-burning version of their SL enduro machines, but once the new SL250 and SL350 four-strokes turned out to be huge hits in the showroom, Honda shelved the idea. Undeterred by this setback, the 335 team pushed forward with building a two-stroke racer on their own. |

This group, which called itself “The Association to Study the Motorcycle”, was not an official arm of Honda’s R&D operation and worked on the motocross program on their own time. Very much like the origins of the first YZ400F four-stroke three decades later, the first CR250 would come from the dreams of a few bright engineers working in their spare time. Since Mr. Honda’s dislike of the two-stroke was well known throughout the company, the team decided to focus their early efforts on attempting to turn one of Honda’s SL125 four-stroke play bikes into a racer.

|

|

Genesis: In late 1971, Mr. Honda finally gave the 335 team the green light to go full throttle with the two-stroke program. Honda put its best engineers on the project and within six-months, had a bike very similar to the final production CR250M. While the production bike did not actually share many parts with this 335C prototype, the basic DNA of the Elsinore is plainly evident. |

In May of 1969, the team would enter their highly modified SL125 into its first motocross race, at the Fukuoka round of the Japanese Motocross Nationals. From the start, it was plainly evident that their highly stressed thumper was not going to be competitive with the much lighter and faster two-stroke race bikes. While the bike finished the race (no mean feat at the time), it was made acutely clear that some rethinking of their plan was in order. In the eyes of the engineers, Mr. Honda’s refusal even to look at the possibility of building a two-stroke was very likely going to leave them at a severe competitive disadvantage going forward.

|

|

Offering 7.1 inches of travel, the Elsinore’s Showa forks were considered very good in ’73. They were light and well damped, but lacked the leading axle design, plush feel and steering precision of the best Maico forks of the day. |

While this initial racing effort may have ended in failure, the information gained would turn out to be vital to Honda’s future. The struggles of the team would bring light to the fact that Honda needed to at least consider developing a two-stroke motor going forward. In early 1971, The Association to Study the Motorcycle would receive approval from Honda’s R&D department to begin developing an all-new two-stroke power plant (code named “335”) to be fitted into the chassis of Honda’s new SL250 four-stroke. The resulting SL250-T was planned to be Honda’s first attempt at a two-stroke machine, but after the four-stroke SL250 turned out to be a huge success on its own, the two-stroke program got back-burnered by corporate once again. With Honda shutting down the program, the future of a two-stroke Honda was very much in doubt.

|

|

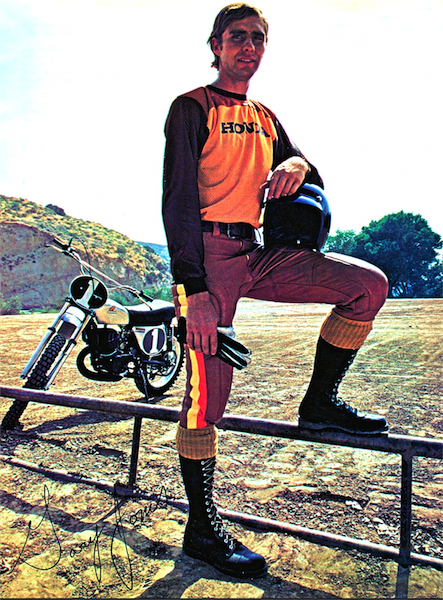

With the introduction of the new Elsinore, Honda knew they wanted to make a splash. They did just that by luring the reigning 250 National Champion, Gary Jones away from Yamaha. Gary would prove to be a wise investment for Honda, taking the new Elsinore to the 1973 250 National title. |

Even though the SL250-T program was officially shut down, some of Honda’s engineers continued to work on developing a new two-stroke racing motor. Before mothballing the initiative, Honda had procured a few competitors to use for reference and the team dissected them in an attempt to discover their secrets. Using a Husqvarna as a baseline, the team went to work putting together a prototype. The first machine, codenamed 335A, used a chassis based on the Husky and various parts cobbled together from other machines (even infamously using a Yamaha DT-1 tank). The second attempt, codenamed 335B was much less cobby, and closer to something that might actually get produced. After some initial testing, Honda’s two-stroke skunk works team decided it was time to try out their creation in real competition.

|

|

While the Elsinore broke new ground with its reliability, ridability and performance; it was actually quite conventional in design. There was no rotary-valve, reed-valve or fancy electronic ignition, just a well designed port layout and careful execution. |

On August 22, 1971, the 335B made its racing debut in the All Japan Motocross Championships (AJMC). Since this was not an “official” Honda effort, the team had wanted to keep the project as low-key as possible, but the press was quick to catch on. Although the bike did not finish the event due to suspension issues, the motor performed admirably and the bike generated a lot of interest. The Japanese enthusiast press was quick to jump on the fact that Honda was apparently going back on their claim to not build a two-stroke. Once the 335B prototype made the Japanese motorcycle magazines, a huge amount of attention was focused on the Associations’ little pet project. With the cat out of the bag, the time had come for Honda to make a decision about the future of their two-stroke program.

|

|

Short lived: In the spring of 1973, this was the baddest 250 money could buy. A mere six months later, its performance would be eclipsed in every way by Yamaha’s revolutionary YZ250A. |

In the fall of ’71, The Association to Study the Motorcycle made a proposal to Mr. Honda himself on the merits of going forward with the two-stroke project. After hearing the proposal, Mr. Honda agreed to green light the project and promised to put the full might of Honda Motors behind the effort. After the meeting, Mr. Honda stated that if Honda was going to build a two-stroke, “it had better be the best two-stroke in the world”.

|

|

The chassis for the CR250M was manufactured out of genuine chrome-moly steel tubing. This was both lighter and stronger than the butter soft and heavy steel typically found on Japanese machines of the day. At 57.1 inches, the Elsinore’s wheelbase was slightly long, giving the CR excellent stability at the expense of steering precision. |

Now an official Honda project, the bike’s codename was changed to 335C and fast tracked for development. The same engineers that had developed Honda’s incredible road race machines in the sixties would now be tasked with creating the world’s best two-stroke 250. In November of 1971, Honda began recruiting riders to race and develop the new bike. In March of 1972, the first official works Honda two-stroke motocross bike made its debut at the first Japanese National of the year. Now officially referred to as the RC250M, the bike would suffer from some overheating and reliability issues, but finish sixth overall.

|

|

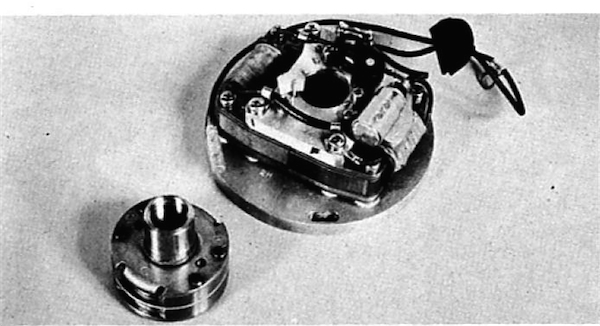

Even though the Elsinore used old school points instead of a fully electronic ignition, it was still more reliable than the European competition. |

|

|

In 1973, Gary Jones had the benefit of full works equipment on his #1 RC250. This meant a reed-valve intake, works electronic ignition, longer travel suspension and a sharper turning chassis. Although the full works equipment offered additional performance, reliability issues would cause Gary’s dad (and mechanic) Don to switch to highly modified stock components by mid-season. |

After the troubles at their first outing, Honda’s engineers quickly went back to work sorting out the RC250M. The road race engineers had no experience with motocross and quickly found the two disciplines to be very different. Thankfully for Honda, however, these were some of the smartest engineers the world had to offer and Suzuki had already done a lot of the trailblazing for them some years earlier.

|

|

At the time of the Elsinore’s introduction, its 4.1 inches if travel and non-adjustable Showa shocks were considered quite good. The only real issue riders had with the CR’s rear end at the time, actually had to do with the cheap nylon bushings used in the swingarm pivot. Over time, they would wear, causing excessive play and eventually, expensive failures. |

After three months of further development, the team decided to enter the bike in the Kannabe round of the AJMC in June. This would be the sixth round of the series and Mr. Honda himself would be in attendance, adding a lot of pressure for the team to show well. Amazingly, the bike would not only impress, it would win! With Honda factory rider Taichi Yoshimura (yes, the guy behind the RS-Taichi gear worn buy JMB and Jeff Mataisevich in 1992) at the controls, the bikes would holeshot both motos and take the overall with a 2-1 moto score. A mere eight months after getting the green light from Mr. Honda, the RC250M would sit at the top of the victory podium.

|

|

One of the few weak links on the original Elsinore was its mediocre brakes. Even by 1973 standards, these were not great binders. |

|

|

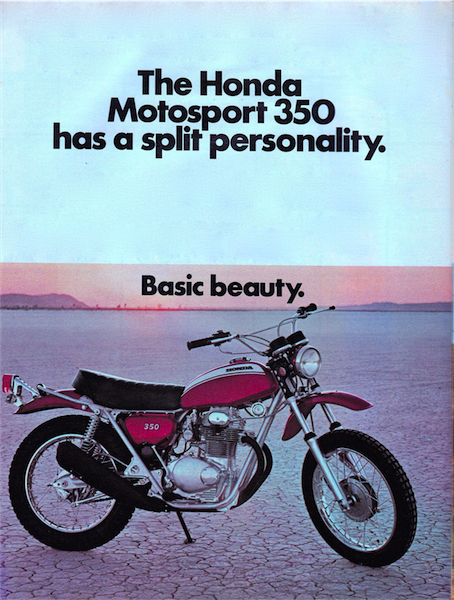

One interesting bit of trivia about the CR250M, is that Honda actually considered leaving the iconic Honda wing off entirely. Early on, it was thought by some in the company that the name Elsinore (named for the famous Elsinore GP) would carry more cache with racers than the name Honda, which was known primarily for its friendly street bikes. By the time the Elsinore made production, the iconic wing was back on the tank. |

|

|

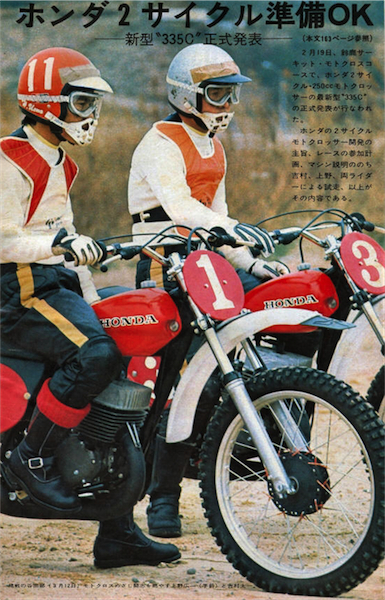

In June of 1972, Taichi Yoshimura (#3) would give Honda its first ever motocross victory at the Kannabe round of the All Japanese Motocross Championships. |

|

|

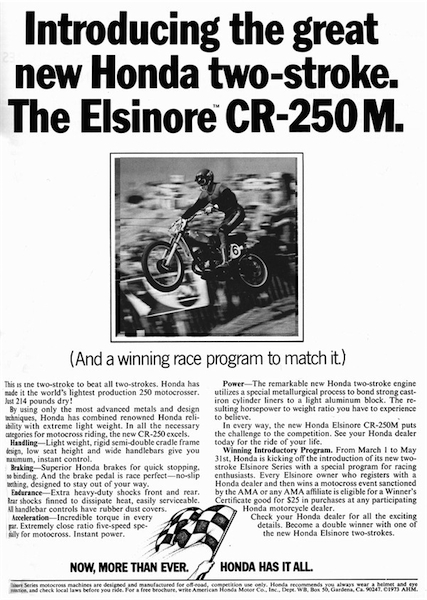

Not exactly an eye catcher, Honda’s ad agency could have used a little polish in ’73. |

Amazingly, only a few months after the success of the RC250M in Japan, Honda would unveil its production version, the CR250M to the world. The production bike looked very similar to the works version, but lacked its lightweight components and Factory trickery. Even though the CR was not an exact works replica, it was by far the most race-ready production machine ever produced up to that time. Unlike the typical European and Japanese bikes of the day, the CR250M Elsinore (so named for the small Southern California town that hosted the Elsinore GP in the early seventies) could actually be ridden off the showroom floor and taken right to the track. No need to hack the frame, throw away the shocks or hog out the ports. It was fast, light, reliable and maybe most importantly, affordable. It was the right bike, at the right time, and it took off like a rocket in the showrooms.

|

|

Details: The new Elsinore was by far the best finished production machine available at the time. “Unbreakable” plastic fenders (at a time when metal or fiberglass were the standard), lightweight magnesium cases, quality levers (with trick end and hinge covers) and high quality alloy castings, set the new Elsie apart. |

With the arrival of the Elsinore (a name the company actually considered using on the tank instead of Honda early on), Honda turned from a maker of scooters and “nice people” bikes, to a motocross power overnight. The Elsinore turned starting gates to a sea of green and silver and converted thousands of riders to buying Japanese. Although the CR was a massive success, its time in the spotlight was short lived. A mere six months after the arrival of the Elsinore, and new faster, lighter and more advanced (albeit much more expensive) machine arrived to steal the Honda’s thunder. The groundbreaking new Yamaha YZ250A would start a Japanese performance arms race that would see the Far East manufacturers dominate the sport by the end of the decade.

|

|

A mere few months after the Elsinore would makes its debut, it would be eclipsed in performance by Yamaha’s new “works replica” YZ250A. The new YZ was incredibly trick, rocket fast and outrageously expensive. Aimed squarely at pro riders (Yamaha offered the MX250 for the less skilled enthusiast), the Y-Zed was lighter, faster and at $1850, nearly twice the price of a stock CR. |

|

|

In March of 1972, Honda announced a machine that would change the sport of motocross forever- the 1973 Honda CR250M Elsinore. The Elsie was light, fast, affordable and ready-to-race right out of the crate. Maybe best of all, it was beautifully finished and reliable, something none of the machine’s competitors could claim. |

Even though its reign at the top of the sport was short, no one can deny the original Elsinore’s significance. It was the bike that made owning a Japanese machine cool and changed peoples expectations for quality and performance. It was the very definition of a game changer, and maybe most remarkably, nearly didn’t happen.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter-@TonyBlazier