For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the bike that helped spark Honda’s 1980’s renaissance, the 1983 CR125R.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the bike that helped spark Honda’s 1980’s renaissance, the 1983 CR125R.

|

|

In 1982, Honda was not yet the showroom powerhouse they would become by the end of the decade. Lackluster quality, oddball design choices and stiff competition all conspired to keep them behind the yellow competition. For ’83, Honda would finally turn the tide with an all new CR125R that could go toe-to-toe with the competition. |

In 1973, Honda shocked the motocross world with their first 125 two-stroke race bike, the CR125M Elsinore. The little Elsie was faster, better suspended and better built than anything ever seen in the small-bore class and a colossal success for Honda. Virtually overnight, starting lines from coast to coast were awash in the little silver-tanked buzz bombs.

|

|

In 1974, Honda took the motocross world by storm with their revolutionary new CR125M Elsinore. It would be a full decade before Honda would once again sit atop the 125 class standings. |

Interestingly, after this immense initial success, Honda would more or less take the rest of the decade off. Stale retreads and mild makeovers would be all that Elsinore fans would have to look forward to for the next five years. As Honda faltered, those early seas of silver quickly gave way to yellow, as Suzuki and Yamaha took up the torch of 125 supremacy.

|

|

For 1983, Honda completely redesigned their 125 class mill. The new 122cc, 55.5 x 50.7mm piston port motor was lighter and more compact for ’83, shaving off a full two pounds of weight and 14mm of width from ‘82. While the new motor offered better low-end and midrange, top-end was still lacking compared to the rocket-fast KX125. |

In 1979, Honda would finally pony-up for a redesign of the old girl, but the results would be less than spectacular. A bizarre 23’ front wheel, anemic motor and pathetic suspension would once again relegate the Elsinore to back of the pack status in ’79. The ’80 model would fix the CR’s power deficiency, but do little to alleviate its suspension woes. A complete ’81 redesign would bring the red tiddler into the new decade with radical styling, a water-cooled motor and a revolutionary monoshock suspension system Honda labeled “Pro-Link”. While the new bike was certainly modern, it was also overweight, underpowered and poorly suspended. Once again, Honda was relegated to eating roost from the awesome RM125.

|

|

Grip it and rip it: While the motor may have failed to impress, the same could not be said of the CR’s chassis dynamics. The little red rooster turned, jumped and responded like no other 125 before it. After a decade of clankers, Honda nailed the magic formula in 1983. |

The ’82 model would bring with it another redesign, and for the first time in nearly a decade, the Honda would actually be in the hunt. Power was improved, but the bike’s handling, suspension and ergonomics were still a step behind the best in the class. For Honda, things looked to be finally moving the right direction, but there was still some work to be done if they were going to wrest the crown of top tiddler away from Suzuki.

|

|

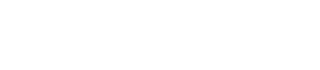

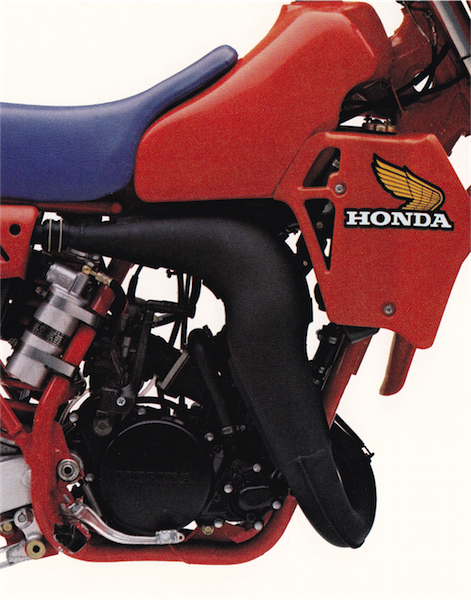

One significant change for ’83 was the incorporation of an all new coolant system for the CR125R. The new system lowered the center of gravity by moving the radiators a full two inches lower on the chassis and also narrowed the motor with a redesigned water-pump that was both lighter and more compact. |

With the ’83 CR125R, Honda took a clean sheet approach. Virtually nothing was carried over from he ’82 model and literally everything was scrutinized in an attempt to extract more performance. An all-new chassis improved handling and lowered weight. Revised suspension lowered seat height (a full two inches over the ’82), improved control (more adjustments) and further lowered weight. An all-new motor was lighter, narrower and more powerful than before, offering a wider spread and more torque. All-new bodywork improved ergonomics with a new safety seat, low-boy tank and lowered radiators. Topping off the improvements for ’83, was a new coat of orange-mist paint for the plastic and frame taken directly from the ’82 Factory bikes. On paper, the new bike looked to be a world beater, but as always, the true test would be on the track.

|

|

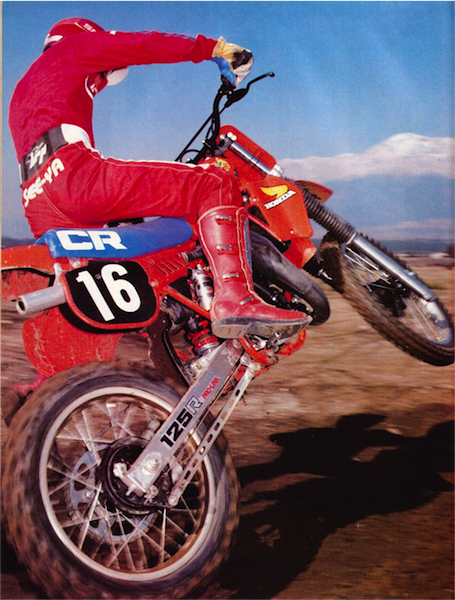

The 1983 125 National season would feature an epic year-long battle between Team Honda’s Johnny O’Mara, Team Kawasaki’s Jeff Ward, Team Suzuki’s Mark Barnett (the three-time defending national champ) and Team Yamaha’s rookie, Ronnie Lechien. In the end, the title fight would go down to the final moto of the year, with O’Mara coming out on top by a mere 9 points over Jeff Ward. |

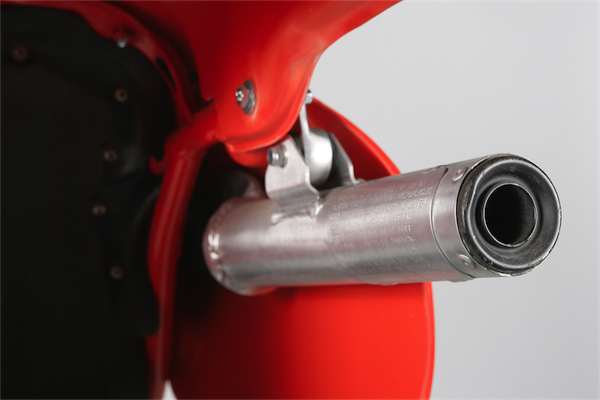

In 1982, Honda had delivered a fun-to-ride, but difficult-to-race powerband on their 125. Nearly every tester enjoyed its punchy mid-range and lively hit, but found its rather narrow spread difficult to manage in the heat of battle. It was fast for a short period of time, but difficult to keep in its narrow sweet spot. For ’83, Honda tried to broaden the torque curve on their 122cc reed-valve racer. All-new cases moved the final drive from the right to the left (done to give the motor a narrower profile) and a new cylinder and head lowered the exhaust ports, enlarged the transfers and bumped the compression ratio from 8.3:1 to 8.6:1. A new reed-valve improved breathing and a new pipe (with a trick alloy silencer) enhanced exhaust flow. Topping off the motor changes were a new coolant system that was both lighter (two pounds) and less power sapping, a new clutch and revised ratios in the transmission.

|

|

In 1983, Honda introduced a lineup of bikes that was top-to-bottom the best ever offered by Big Red. These machines would sow the seeds for a decade of Honda domination. |

So what did all these changes add up to on the track? In truth, the ’83 CR125R mill was notably improved, but still no world-beater. Power off the line was still merely adequate enough to get the bike in motion and far from the CR’s strong suit. Midrange, however, was improved over ’82 and plentiful. After its strong midrange hit, there was little pull to be had as the power tapered off notably on top-end. Just as in ’82, it was necessary to have a fast left foot to keep CR surfing that midrange surge. If you flubbed a shift and fell off the pipe, you were in trouble, but if you could keep the red tiddler on the bubble, it was more than competitive with the other 125’s.

|

|

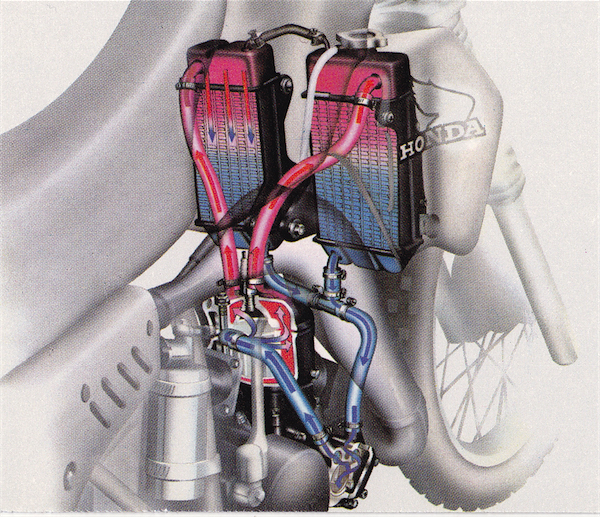

A major league diet for ’83 shaved six pounds of unwanted baggage off Honda’s 125. This combined with a two-inch lower seat height, more centralized mass and greatly improved ergonomics helped make the CR125R the most flickable bike of ’83. |

While the motor on the new CR was nothing to write home to Lovely Louella about, the rest of the bike was a superstar. First up on the list of the little Honda’s list of virtues, was its incredible handling. Over the years, Honda had done itself no great favors with the chassis dynamics of its eighth-liter racers. Early Elsinore’s suffered from too little suspension, while later iterations went the other direction with skyscraper seat heights and floppy front ends. For ’83, Honda finally got it right with a nearly perfect juggling of materials, geometry and design.

|

|

O’Show inspired antics were no problem on the feather-light CR. |

Some of the credit for the handling prowess of the ’83 CR certainly went to the bike’s feather-light 192-pound fighting weight. This was a full six pounds lighter than the ’82 model (which was four pounds lighter than the porky ’81). Literally everything was scrutinized for ’83 in an effort to trim unwanted pork. Components like the silencer, Pro-Link linkage, brake lever and clutch plates were all changed from heavy steel to lightweight alloy alternatives. The wheels and brakes were both shaved down for ’83 and shorn with Bridgestone’s latest lightweight rubber. Suspension front and rear was also lighter, with slightly less travel than 1982.

|

|

While the Honda 250 and 480 got beefy 43mm forks, the 125 had to make do with Kayaba’s old-school 38mm sliders. These KYB forks offered adjustable compression damping and 11.4 inches of travel, but no rebound adjustment. In stock form, they were decently plush and well damped for the time, but too soft for fast guys. |

The new chrome-moly frame was stronger for ’83 and offered a fully removable rear subframe for the first time. This new design was slightly less aggressive for ’83, offering more trail, less rake and a half-inch longer wheelbase. In addition to the new angles, a greatly improved center of gravity also aided handling. The new bike mounted the radiators a full two inches lower in in the chassis and mated that with a works-style “drop-tank” that drooped on one side to allow the fuel to sit lower on the chassis. With the narrower tank, two inch lower seat height and up-the-tank saddle, it was easier than ever to get forward on the bike and find the optimal riding position in turns.

|

|

Trick items like the Honda’s fully removable rear subframe were a big deal in ’83. Pioneered on Honda’s works bikes, it would take Yamaha and Suzuki another decade to adopt this maintenance-friendly feature. |

On the track, all that engineering alchemy came together to produce a machine that MXA labeled “the best handling 125 motocrosser ever built.” In one fell swoop, Honda wiped away a decade of handling mediocrity and indignation. The new CR offered a level of turning prowess never before seen on a red machine (unless of course, you counted Maico) and combined it with a light and airy feel that made attacking the track a joy. The little CR tracked straight in the rough, carved turns with precision and flew straight and true off the jumps. It was the best handling bike in the 125 class by a wide margin and a quantum leap forward for Honda.

|

|

The addition of a rebound adjuster on the CR’s Showa shock was big news for ’83. |

The other half of the ’83 CR’s excellent handling story was its suspension package. For ’83, Honda made the rather interesting choice to use two separate suppliers for the CR’s suspension components. Up front, Kayaba handled the forks, while Showa handed the shock out back. While this may have seemed like a bit of an oddball combination, it actually ended up working quite well.

|

|

Like the forks, the Honda’s Showa shock was too soft for serious aerial work, but it did a admirable job of smoothing out the track. While it was not in the same performance league as the Suzuki Full-Floater, the Honda’s Pro-Link was decently plush and raceable in stock condition. |

The new 38mm KYB forks (the CR250R and CR480R got much beefier 43mm stanchions) were actually 13mm shorter for ’83 and offered 5mm less travel than ’82. This was to address one of the biggest complaints riders had voiced about CR125’s since 1979, that they were too tall. The new forks while shorter, actually performed far better than the old units and offered a wide range of compression setting via a screw mounted at the forks (’82 offered a mere 3 settings). While there was no adjustment for rebound (and no fancy cartridge internals), they did come equipped with air caps on each leg to allow fine-tuning of the spring rate.

|

|

Usually horsepower wins the day in the 125 class, but in ’83, the best overall bike was not the fastest. |

In terms of performance, the Honda’s KYB forks were rated the best of 1983 in the 125-class. Due to the limitations of the simple damper-rod system none of the fork class of ’83 could be considered without flaw, but the Honda did the best job of combining bump absorption with a degree of plushness. Some riders felt the forks were too soft initially and could use stiffer springs, but they were raceable in stock condition and less harsh than the competition.

|

|

During the heyday of the works bike, virtually nothing was shared in common between the Factory bikes and the machines you would find on the showroom floor. While the two bikes shared a passing resemblance (mainly due to the color scheme), you were not likely to find a power-valved, cartridge-suspended, aluminum-tanked, dual-disc’d CR125R at Billy Bob’s Cycle Emporium anytime soon. |

Like the forks, the new remote reservoir Showa shock offered 5mm less travel than ’82 and a great deal more adjustment. Where the ’82 model had offered only 4-way compression adjustment (and no rebound adjustment), the new shock ponied up a 12-way compression adjustment and 20 adjustable rebound settings. Like the rest of the bike, the rear suspension was also lighter with a new swingarm that trimmed ounces and lightweight alloy linkage that replaced the heavy forged steel components of ’82.

|

|

Another feature the CR125R did without in ’83 was the larger CR’s powerful dual-leading shoe binders. |

On the track, the little Honda’s suspension worked well for anyone less than 160 pounds. The rear end was plush and took small hits well, but could be bottomed with a “thud” on big hits. In these situations, the bike took the hit well and never hopped, bucked, or did anything weird. For heavier guys, a step up in spring rate and perhaps even an aftermarket alternative were recommended. Overall, the CR’s shock was much improved and certainly the best ever seen on a 125 Honda, but still not in the same league as the omnipotent Suzuki Full-Floater.

|

|

Sano touches like this trick alloy silencer set the Honda apart in the 125 class. |

As for detailing, the little Honda was a step ahead of the class in most areas. Plastic quality, fit and finish were all world class for the time and a huge improvement over the industrial grade workmanship seen on the Kawasaki and Suzuki. Things like the bars, grips, perches and levers showed Honda’s attention to detail and were a step above anything else available at the time (and would continue to be so for the next decade). Touches like the fully removable rear subframe were taken directly off the Honda Factory race bikes and greatly aided maintenance.

|

|

One of O’Mara’s toughest competitors during the ’83 season was Yamaha’s 16-year old phenom, Ronnie Lechien. Lechien would card 3 overall victories in the series (one more than O’Mara), but be undone by subpar showing at Foxborough (12th) and Washougal (10th). |

One area where the Honda did lag behind was in the braking department. Unlike the 250 and 480, the CR125R had to make do without the trick dual-leading-shoe binder found on David Bailey’s works bike. Instead, the little CR had to make do with the same single-action brake system in use since the turn of the century. While it was the best of the drums, it was no match for the awesome power of the KX125’s hydraulic disc.

|

|

In 1983, Honda produced a CR125R that bested the 125 class in spite of having less power than the competition. It was incredibly trick, flawlessly crafted and capable of handling rings around any other 125 on the track. In ’83, that was enough to take home the title of the top 125 in the land. |

In 1983, Honda introduced a line of machines that would turn the tide from yellow to red for the first time in a decade. The all-new CR125R was the first shot in a barrage that would see Honda go from also-ran, to top dog in all three classes. The new CR125R signaled that Honda was indeed serious about motocross and determined to take the top spot in the showrooms, as well as the racetrack. While it did not yet possess the horsepower advantage it would gain in later years, the ’83 CR125R sowed the seeds for a decade of dominance with faultless handling, perfect ergos and sano looks. It was not perfect, but it was the best 125 of ’83 and the progenitor of a dynasty.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier