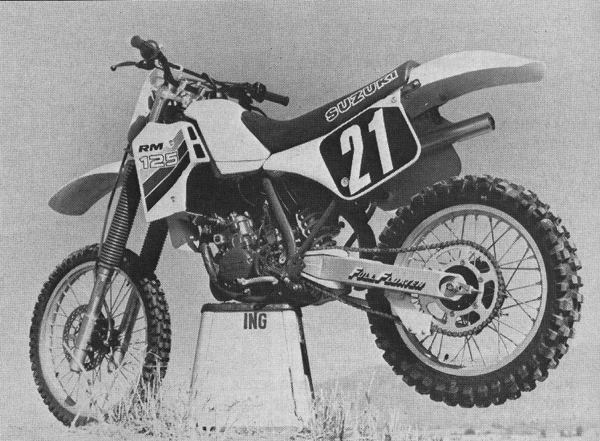

For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the first of the blue-motored Suzuki’s, the 1986 RM125G.

For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the first of the blue-motored Suzuki’s, the 1986 RM125G.

|

|

In 1986, Suzuki threw the kitchen sink at their 125 program. An all-new motor, chassis and suspension looked to turn around fortunes that had been trending in the wrong direction for the better part of a decade. |

The mid-eighties were a tough time to be a Suzuki fan. As one of the pioneers of the Japanese motocross movement, Suzuki had been enjoying quite a run in the 1970’s. They were the first Japanese manufacturer to win a 250 and 500 World motocross title with Joël Robert and Roger Decoster at the controls. Then they proceeded to absolutely dominate the 125 division, sweeping the first ten 125 World Championships run. From 1975 until 1984, no other brand even got a sniff at a 125 World title. Their stock bikes were great and their works bikes were amazing. They were a small manufacturer, showing up competitors with many times their resources and budget.

|

|

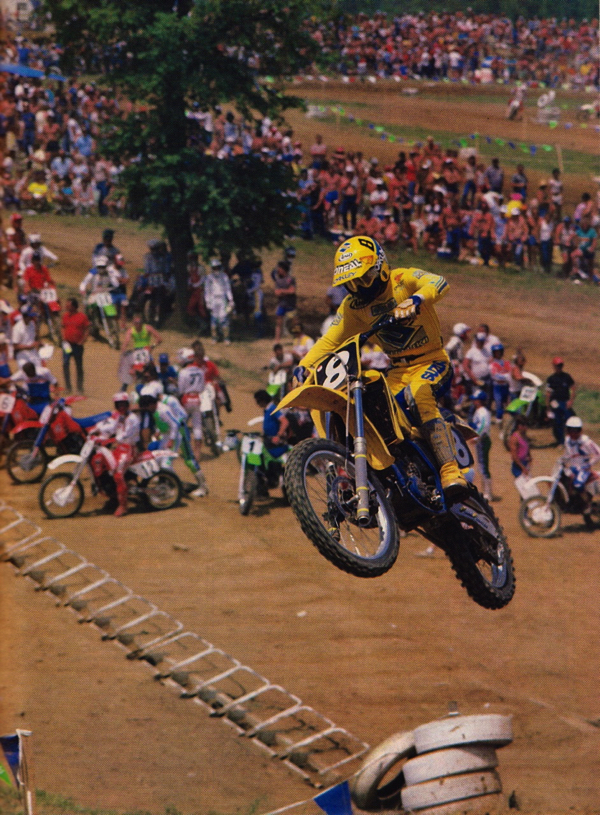

The Bomber: In the late seventies and early eighties, Suzuki was THE brand to ride in the 125 class. They dominated the National and World motocross standings while racking up shootout victories in the enthusiast press. With riders like riders Mark Barnett (pictured above), Eric Geboers, Georges Jobé, and Harry Everts at the controls, the RM125 was nearly unbeatable. Photo credit: Dirt Bike |

Into the early eighties, this domination continued with excellent machines and winning riders. Mark Barnett, Kent Howerton, Georges Jobé, Harry Everts and Eric Geboers all rode Suzuki yellow to National and World titles at the early part of the decade. Their revolutionary Full Floater suspension was the envy of the industry and the ultra-light and advanced RM’s were the bikes to ride.

|

|

Got the boggy bottom blues: From 1983 thru 1985, Suzuki 125s suffered from a serious pony deficit. Their motors offered absolutely no low-end, very little midrange and only a modicum of top-end power. For 1986, Suzuki hoped to remedy this deficiency by spec’ing an all-new semi-case-reed motor that integrated a variable exhaust control device for the first time. |

By 1983, however, the complexion of the motocross landscape was beginning to change. Long an also-ran in the motocross sweepstakes, the sleeping giant of Honda Motor Corporation finally got serious about delivering a decent motocross machine to the public. After KO’ing the industry in 1973 with the first CR125M Elsinore, Honda had been content to sit back and deliver sub-par products for the majority of the decade. Slow, odd handling and poorly suspended, the CR125 had become the perennial whipping boy of Suzuki’s RM125. In 1983, all that finally changed.

|

|

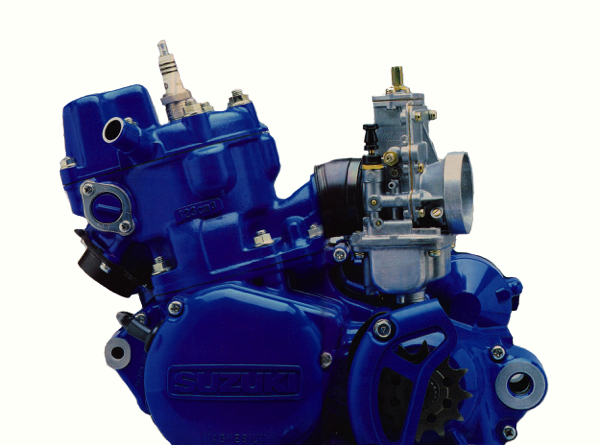

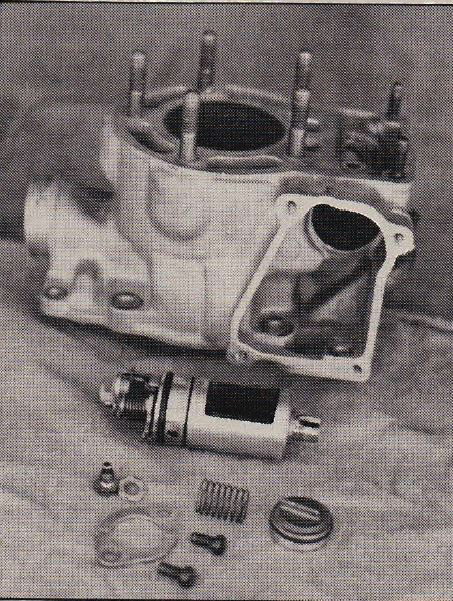

Gyro Gearloose: In 1986, Suzuki introduced their version of an exhaust “power valve” for the first time. Dubbed Automatic Exhaust Control (AEC), the Suzuki system functioned similarly to Honda’s ATAC design. By adding a small sub-chamber and drum-valve to the exhaust port, the AEC could alter exhaust system tuning to suit engine rpm. At low rpm, the AEC rotated the valve to allow exhaust to flow into the chamber, increasing head pipe volume for more low-end power. At higher rpm settings, the drum rotated to cover the sub-port and allow unobstructed flow to the expansion chamber. |

The 1983 Honda lineup was all-new from stem to stern, with radical works bike styling and blistering performance. The CR125R took its first 125 shootout victory in a decade and the once omnipotent RM was relegated to last in a field of much improved 125’s. The RM maintained its top billing in the suspension sweepstakes, but lost out badly in the horsepower wars with a lackluster output and lethargic delivery.

|

|

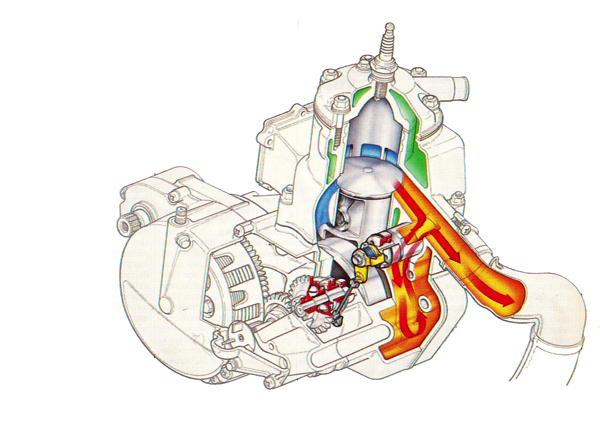

Earthquake: Erik Kehoe was Suzuki’s top gun in the 125 class in 1986. Photo credit: Dirt Bike |

In ’84 and ’85, it would be a repeat performance as the Suzuki engineers tried to squeeze a few more years out of their aging two-stroke mill. The RM offered a smooth delivery that was absolutely devoid of any hit or bark. It bogged off the line and lay down completely if not absolutely wrung to within an inch of its life. To make time on the RM, a rider had to show no fear and commit to leave it pinned come hell or high water. Its suspension continued to lead the class, but in a division ruled by horsepower, its meager output was no match for the rocket-fast KX125.

|

|

Imposter: Probably the biggest Suzuki news of 1986 was the decision to move away from their groundbreaking original Full Floater suspension design. Revered to this day for its amazing performance, the original Floater was excellent on the track, but expensive to produce and cumbersome to accommodate. The new for ’86 eccentric cam Full Floater retained the name of the original, but none of its performance. |

For 1986, Suzuki realized they had to take a hard look at their once omnipotent tiddler and come up with a new plan. The old design was round filed and engineers set about crafting a better RM. An all-new frame was spec’d with lighter, more compact oval tubing for a narrower profile and mated to a completely redesigned Full Floater rear suspension. The anemic ’85 motor was laid to rest and an all-new 123cc mill was installed to pump up the power. Finishing off the package was a fresh coat of bright blue paint for the motor and a set of Bold New Graphics for the seat and tank.

|

|

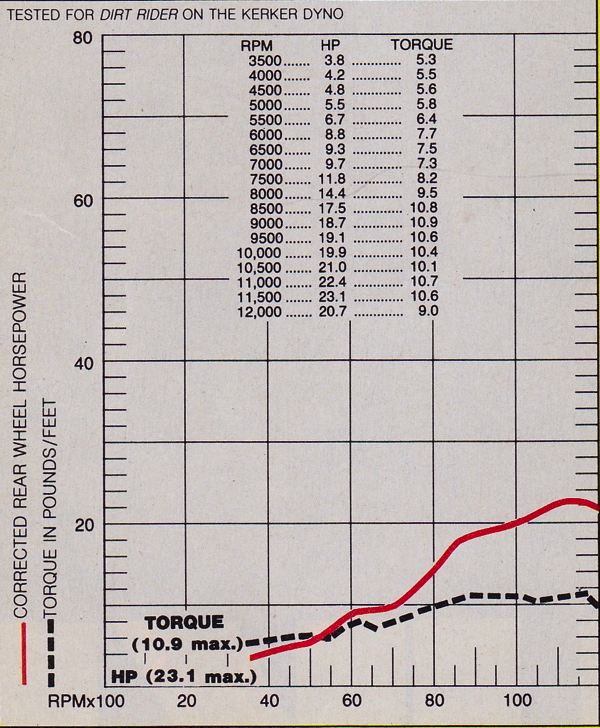

Woof woof: Unfortunately for Suzuki fans, the new power-valved motor proved no more effective than its less complicated predecessor had been. Low-end torque was completely non-existent and the bike made all of its meager ponies at the upper ranges of the power curve. Because there was no usable power below 10,000 rpm, it was critical to keep the throttle pinned and maintain momentum. Once the RM fell off the pipe, you were left fanning the clutch as the white, green and red machines roosted away into the sunset. |

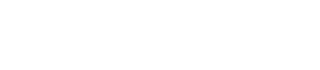

After being drubbed in the horsepower department for the previous three years, Suzuki knew there needed to be big changes in the motor department for 1986. The all-new motor retained the 54 x 54mm bore and stroke of the ’85 model, but redesigned the cylinder to incorporate a “Power Valve” for the first time. Suzuki’s version of a variable exhaust control device was dubbed AEC (Automatic Exhaust Control) and it incorporated a large resonance chamber into the head, but no mechanism to alter port timing (like Yamaha’s YPVS). Similar in theory to Honda’s ATAC, the AEC used a small drum placed at the exhaust port to redirect exhaust flow at low rpm into a resonance chamber for improved low-end power. At higher rpm, the drum rotated to uncover a pass through to allow unimpeded flow to the expansion chamber.

|

|

While the stock RM125 left a lot to be desired, that did not stop Suzuki riders from powering to the bike to the front on several occasions. Team Suzuki riders Erik Kehoe (8) and George Holland (11) (pictured above at Hangtown leading Micky Dymond) split victories at the first two rounds of the 1986 title chase and had the RM’s at or near the front all season. Photo credit: Fran Kuhn |

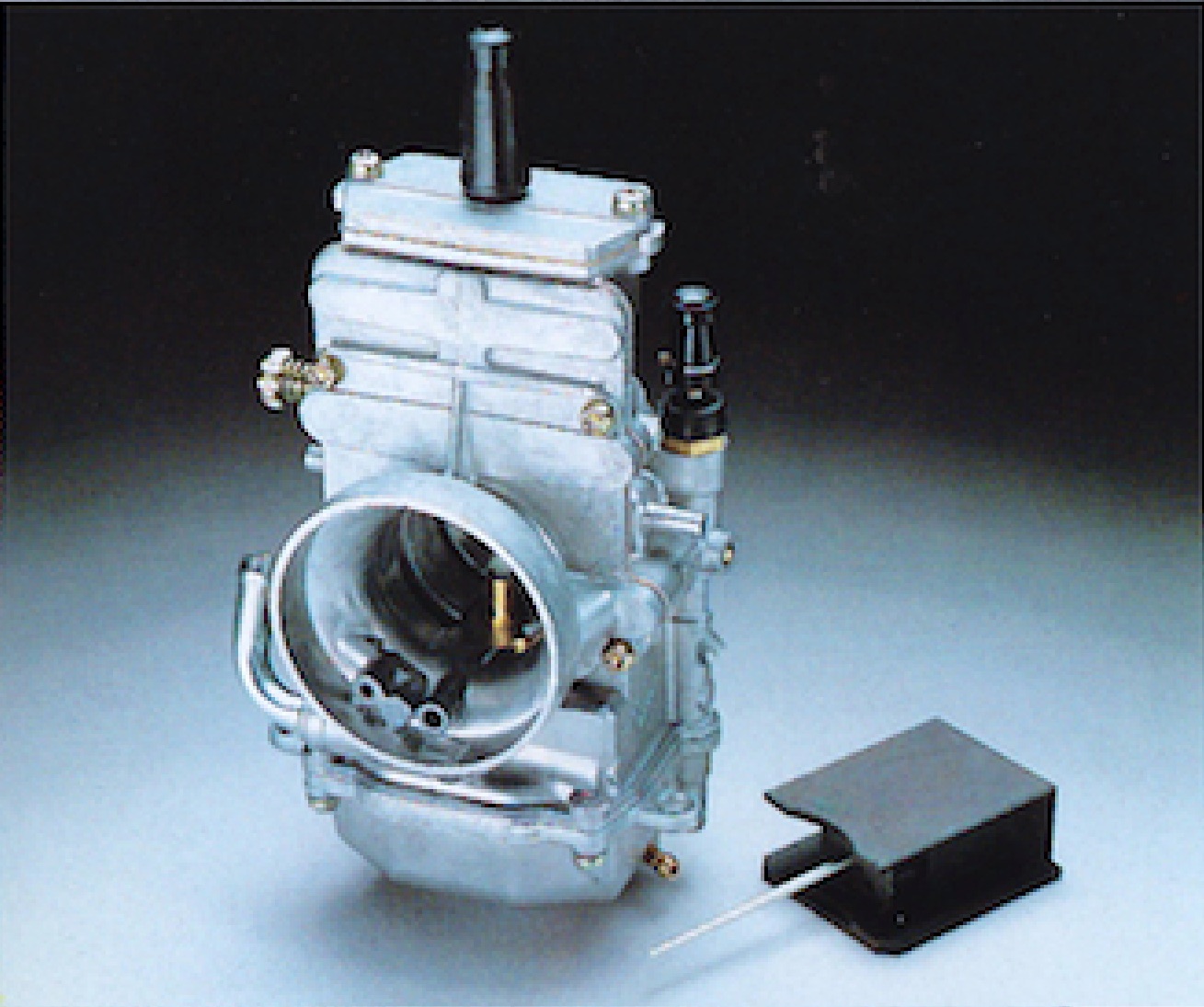

On the intake side of things, the new RM motor retained the unique semi-case-reed intake Suzuki had employed since 1976. Dubbed “Power Reed”, this design looked like a traditional cylinder-mounted intake, but operated differently. Instead of feeding the charge directly to the cylinder, it rerouted it through a single reed valve directly into the crankcase. Feeding the intake was a 34mm flat-slide Mikuni carb and an all-new airbox that moved filter access from the side to the top.

|

|

Amazingly talented riders like Mike Healey made these subpar mid-eighties RM’s look far better than they really were. Photo credit: Mike Gaspar/ Dirt Rider |

While the motor’s appearance was certainly new, its performance was not. All the power improvements promised for ’86 turned out to be so much hyperbole, as the motor ran no better than it had the previous three years. Low-end torque was completely non-existent and the RM was an endless sea of bog off the line. The midrange was little better and the little Zook only started to pick up past 10,000 rpm. Its powerband was razor thin and required a locked right wrist and lots of momentum to make it work. There was no hit, no zip and no brappp, just a long and languid delivery that never really got going.

|

|

DOA: In 1986, the RM125 had the least effective powerband in the class by a wide margin. It lacked low-end torque and gave up almost four horsepower to the other bikes at peak. |

In order to make this anemic powerband work, clutch abuse was an absolute necessity and RM pilots quickly got quite familiar with the lever on the left side of the bar. Thankfully, Suzuki beefed up the clutch for ‘86, but it was still not enough to withstand the constant onslaught. A good 15 minutes of abuse had the plates begging for mercy and they quickly became grabby and uncooperative. The new more compact transmission was also an issue and missed shifts were a constant concern.

|

|

As if being painfully slow was not problem enough, Suzuki’s new 123cc mill proved abysmally unreliable as well. The motor overheated, seized, broke pistons and chewed rings with alarming regularity. The new power valve also had numerous issues and tuners found that the bike actually ran better by bypassing the mechanism altogether and locking it in the open position. |

As to the new AEC, it proved completely ineffectual and even worse, unreliable. There were problems with the governor, which liked to open and close the valve randomly when riding in the rough. This provided a weird sensation as the bike randomly sputtered and cleaned out. Even when operating normally, it tended to provide uneven performance and many tuners found that the bike actually ran better with it disengaged altogether.

|

|

One and done: Since the late seventies, Suzuki’s greatest asset had been its rear suspension. Not always the fastest bike, you could at least bank on its ability to gobble up the bumps. In 1986, that streak came crashing to a halt with the demise of the original Full Floater design. The new Floater suffered from a drag-prone linkage and an overabundance of damping in both directions. Harsh and unforgiving at low speeds, the new shock proved adept only at taking big hits well. This new design would last only one year and get replaced with a more effective linkage in 1987. |

While the lackluster motor was not necessarily a surprise (Suzuki had not built a really great one in half a decade) no one was prepared for the disappointment that awaited in the suspension department. Pretty much since the introduction of the original Full Floater in 1981, Suzuki had owned the rear suspension category. The RM’s were not always the fastest bikes, but you could bank on them offering the best ride.

|

|

The RM’s 34mm flat-slide Mikuni carburetor looked cool, but did very little to aid the Suzuki’s meager output. |

For 1986, all that went out the window with the introduction of an all-new non-full floating Full Floater. The advantage of the original design had been its complex array of links and levers that allowed the rear shock to “float” (hence the name) independently of the frame. Instead of hard mounting the shock to the frame backbone like most suspension, the Full Floater design attached the shock at both ends to articulating levers. By freeing up the shock to move independently, the Full Floater was able to deliver amazing performance and an ultra-smooth ride.

|

|

Butt buster: While the chassis, motor and suspension were all-new for 1985, the RM retained its old fashioned bodywork and layout. Going from seating to standing was incredibly hard on the cramped RM and the seat itself trapped you in place with its scooped out profile and sagging foam. |

|

|

Aerial manners were actually pretty good on the RM and hard landings were taken in stride by the new suspension. Mike Healey demonstrates for Dirt Rider’s camera. Photo credit: Mike Gaspar/ Dirt Rider |

While the Full Floater’s performance was unrivaled, its design limitations eventually caused Suzuki to move away from it. First and foremost was cost, as its complex design was more expensive to produce than the competing systems (yeah, I’m looking at you air forks…). The second strike against it was its overall size, which was much larger and more highly placed than more compact designs like Honda’s Pro-Link.

|

|

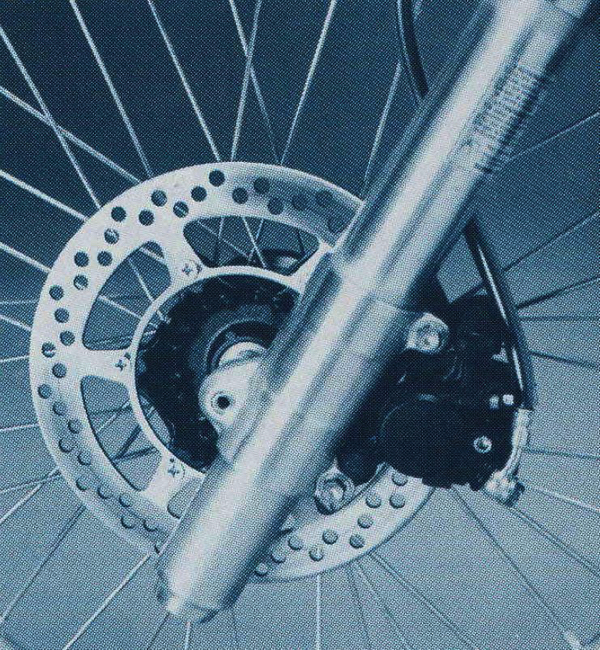

The single-piston disc front binder on the RM125 proved the worst of the ’86 125 crop. Both power and feel were lackluster and well below the class leading Honda’s remarkable pucker power. |

With the design of the second generation Full Floater, Suzuki was looking to both lower the cost of production and the center of gravity of their suspension. The new design did away with the struts and upper link that gave the original its name and instead went with a more traditional arrangement. The new Kayaba shock was hard mounted to the frame at the top and bolted to an all-new bell-crank linkage at the bottom. The new linkage used an eccentric cam to vary the rising rate and offered both a much lower center of gravity and more compact profile.

|

|

Polishing a turd: In 1986, the production rule went into effect in America and Team Suzuki was left trying to squeeze some power out of the anemic production RM. During the summer, both Kehoe and Holland were seen running completely different combinations of aftermarket and works parts in search of more performance. Reportedly, nothing seemed to be able to bolster the bikes woeful lack of torque, but several pipe and porting combinations extracted more top-end power out of the race bikes. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike |

While the new Full Floater accomplished both of Suzuki’s design goals, it missed out in the most important department – performance. The new rear end offered 12.4 inches of travel to go with both compression and rebound damping adjustability and a more compact layout. While less complicated than previous Floaters, it also proved less adept at taming the track. Harsh and unforgiving, it was too stiff on small impacts and transmitted every part of the track to the rider’s backside. Big hits were taken well, but the compression and rebound damping were too heavy in both directions. Making matters worse, the linkage proved prone to a great deal of drag. The stiction in the eccentric cam was bad enough to actually interfere with the shock’s movement and hinder the Kayaba’s ability to react in the rough. As the linkage broke in, this draggy feeling lessened slightly, but never completely went away.

|

|

Cartridge forks were not yet a reality in the 125 class in 1986 and most suspension could not handle a wide range of performance demands. The RM125’s 43mm Kayaba forks worked well on big hits, but were harsh and unforgiving on smaller impacts. |

Up front, the new RM offered a 43mm set of Kayaba forks with 11.8 inches of travel and 8 adjustable compression settings. Like the shock, they proved harsh on small impacts, but very good at taking hard hits. In these days before cartridge forks (they would not come to the 125 class until 1987), none of the manufacturers did a great job at offering both plush performance and good bottoming resistance. It was always a compromise and the RM skewed toward the mega-leap end of the spectrum. If you were fast and charged hard, you liked them, but if you were less aggressive, they felt busy and unforgiving.

|

|

A rear drum brake was still de rigueur in the 125 class in 1986 (only Kawasaki offered a rear disc) and the RM’s unit offered mid-pack performance. |

In the chassis department, the new oval tubed frame offered middle of the road performance. Cornering was decent (but not on par with the razor sharp Honda) and the bike was fairly stable (but not as rock solid as the Yamaha), but no one was fighting to get on the RM. By far the Suzuki’s biggest liability was its ergonomics, which were odd and uncomfortable. The seat was low and bars were high, leaving you in a “sit up and beg” posture. The bike was extremely cramped for anyone over 5’6” and it was a chore to go from sitting to standing. Adding to the aggravation was a seat that sacked out after only a few rides and left you basically sitting on frame rails by the third tank of gas. In addition to offering poor ergonomics, the RM’s old school bodywork gave the bike a very dated look and feel. Compared to the zoot capri Honda, the Suzuki looked like a holdout from another decade.

|

|

Pin it and pray: With its narrow powerband, lack of torque and cranky clutch, keeping the little zook at full boil was no easy task. Gearing it down two teeth, bolting on a Pro Circuit pipe and learning to never shut off were a Suzuki rider’s only hope in 1986. Photo credit: Motocross Action |

In addition to its looks, the RM offered by far the poorest detailing in the class. Every bolt, screw or nut had washers, spacers and assorted froof attached to it that invariably fell off and made its way into the dirt every time a part or piece was disassembled. Removing the rear wheel alone was an absolute nightmare with its odd nut sizes, half a dozen spacers and washers to contend with. The bolts and screws themselves were all of poor quality and there seemed to be no rhyme or reason to their size selection. Even though the RM featured a front disc, its performance was extremely poor and by far the worst in the class.

|

|

Always the bridesmaid: The 1985 and 1986 seasons proved Erik Kehoe’s best shots at 125 National title. He was fast enough to be champ both seasons, but inconsistency proved his undoing. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

Overall reliability of the new motor proved less than impressive and bike suffered several issues. In addition to the aforementioned AEC gremlins, there were problems with piston durability, seizures and chronic overheating. The RM chewed through top ends like candy and if left unchecked, a loud BANG was imminent. The new airbox proved a disaster and finding a good seal was nearly impossible. Just getting the filter in and out was a nightmare and you were 100% guaranteed to drop dirt into the airboot while wrestling the filter out of the tiny new hole it was supposed to come out of. Constant vigilance and a steady diet of race gas were your only defense, and even then, you had a 50/50 chance of the RM blowing itself into a million little pieces. At least the shiny new blue motor was pretty…

|

|

In 1986, Suzuki changed virtually everything, but ended up right back where they started. The new motor and suspension were a disappointment and even its best attributes were average at best. It was all-new and already outdated. In a class were technology moved at warp speed, that was not nearly good enough. Photo credit: Motocross Action |

Overall, 1986 RM125 proved to be a massive disappointment for Suzuki and its legions of loyal fans. After dominating the 125 class for nearly a decade, they released yet another dud with the all-new G model. Unfortunately, the exhaust gizmos, eccentric cam doohickeys and fancy blue paint all merely added up to a new bike with the same old lackluster performance. For Suzuki, it would be another five years of misery before they could recapture their lost glory and truly offer an RM125 capable of going head to head with the best bikes in the land.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier