For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at one of Yamaha’s mid-eighties mid-range missiles, the 1988 YZ125.

For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at one of Yamaha’s mid-eighties mid-range missiles, the 1988 YZ125.

In its third year of production, refinement was the name of the game for Yamaha’s 125 in 1988. A new cartridge fork, silver accents and some minor motor mods highlighted a largely unchanged package. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The 1980s were an up and down decade for Yamaha’s 125 motocross program. At the start of the decade, the YZ was on top with the best bike in the class. It was fast, light and generally did the best job of going fast around the racetrack. In 1981, however, the balance of power shifted back to Suzuki with the arrival of their groundbreaking Full-Floater suspension system. The ‘81 RM125 laid waste to the competition and made the old-school monoshock YZ look like yesterday’s news. In 1982, The YZ fought back with an all-new Power Valve motor that roosted on the competition, but its cranky rear suspension and oddball handling kept it from overtaking the RM at the top of the standings.

|

|

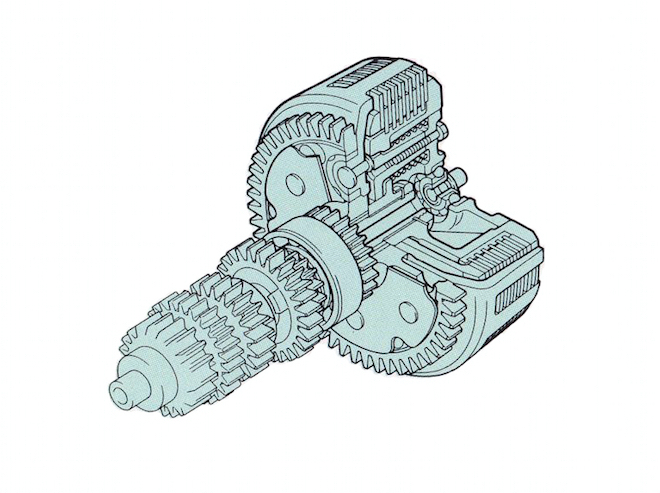

The switch to a new case-reed motor in 1986 fixed the YZ’s woeful horsepower deficit, but did nothing for its cranky transmission. A new clutch, beefed-up gears, and a larger main shaft looked to smooth out the YZ’s notoriously poor shift action for 1988. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

For 1983, Yamaha finally moved the radiator from the handlebar to the front of the tank, trimmed the weight and dialed up a decent rear suspension design. The improved handling and suspension were welcome upgrades, but once again the YZ was forced to play second fiddle; this time to the upstart CR125R.

|

|

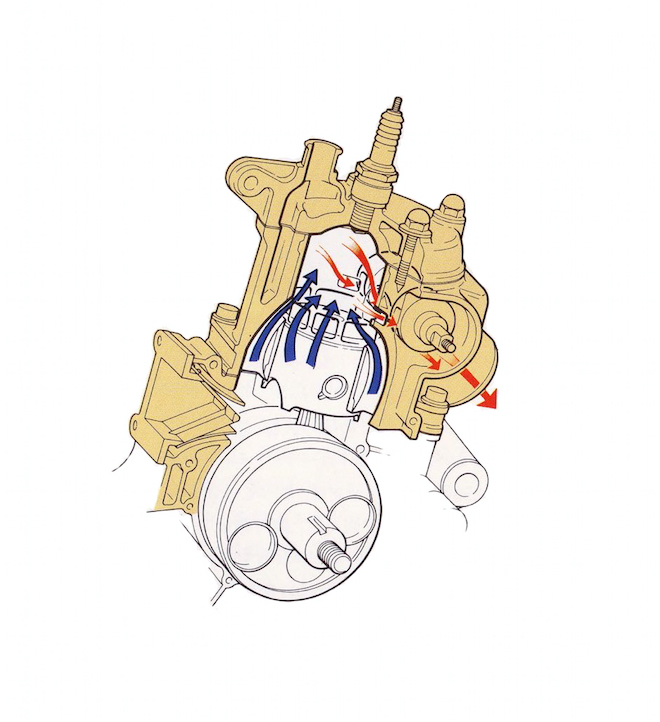

In addition to the transmission updates, a relocated YPVS, new porting and an enlarged reed-valve aimed to broaden the YZ’s potent, but narrow power delivery. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

In 1984, things started trending in the wrong direction for the YZ125. An all-new bike turned out to be the dog of the class and the YZ slid from second to a distant last in the 125 standings. The 1985 season brought with it a new look, but the same old bow-wow of a motor. The ’85 YZ was slow, poorly suspended and a complete embarrassment on the track. Hopping it up only made it less reliable, while doing nothing for its meager output.

After two years of utter futility in the 125 class, it was time for a fresh start in 1986. An all-new YZ125 moved to case-reed induction and introduced a slim layout that rivaled the Honda for fit and feel. The new bike was worlds faster than the ’85, but harder to ride than the omnipotent CR. Its midrange motor was fast, but the overall spread was narrow and the notchy gearbox made keeping it in the sweet spot difficult. Overall, it was the most improved bike of ’86, but not quite up to capturing the title of top 125 in the land.

|

|

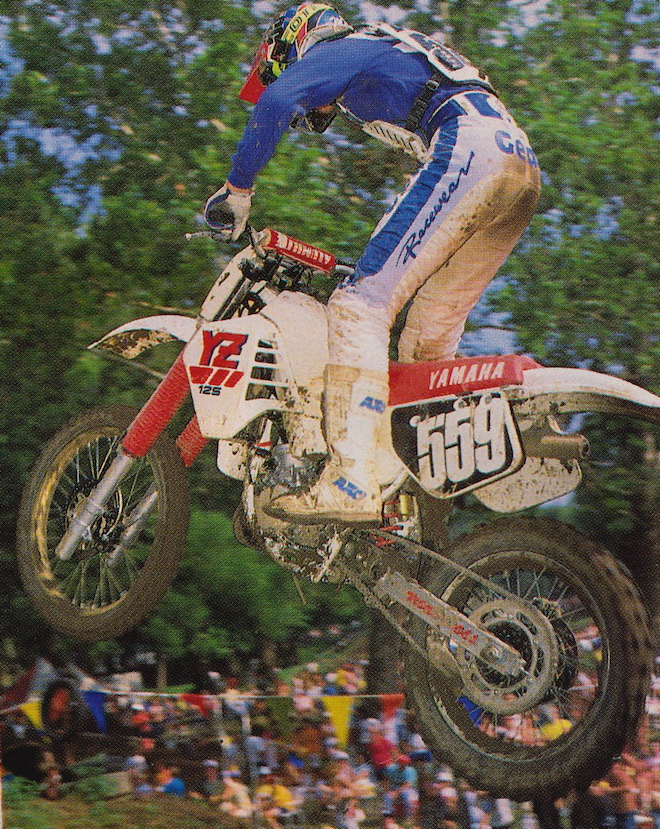

In 1988, Yamaha had quite a stable of young talent in the wings. Certainly the highest profile of which was North Carolina’s Damon Bradshaw (68), who would pilot his YZ125 to an impressive fourth overall in his pro debut at Spring Creek in 1988. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

For 1987, Yamaha ditched the red radiator shrouds and worked on refining the solid ’86 package. The new bike offered a beefy low-end punch and some of the worst forks ever seen on a motocross machine. The new Travel Control Valve (TCV) Kayaba forks were incredibly harsh and virtually unridable in stock condition. They held back an otherwise solid package and made the YZ cannon fodder for the redesigned Honda CR125R.

|

|

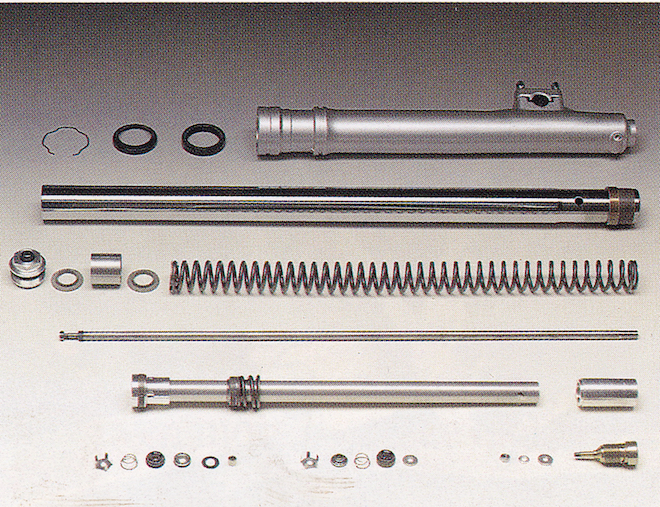

By far the biggest improvement made to the performance of the 1988 YZ line was the adoption of Kayaba’s new 43mm cartridge fork. The cartridge design allowed a wider range of adjustment, less oil aeration and far smoother performance than the conventional damper-rod forks it replaced. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

With yet another disappointing season in the rearview mirror, Yamaha set about bringing their second-banana up to snuff for 1988. First up on the agenda was an upgrade in suspension. The unloved TCV forks were retired and replaced with Kayaba’s new 43mm cartridge sliders. These new units offered far finer damping control and a quantum leap in performance. Complementing the new forks were a new BASS-less shock, revamped motor, new bars, better brakes, revised graphics and a new coat of silver paint for everything.

|

|

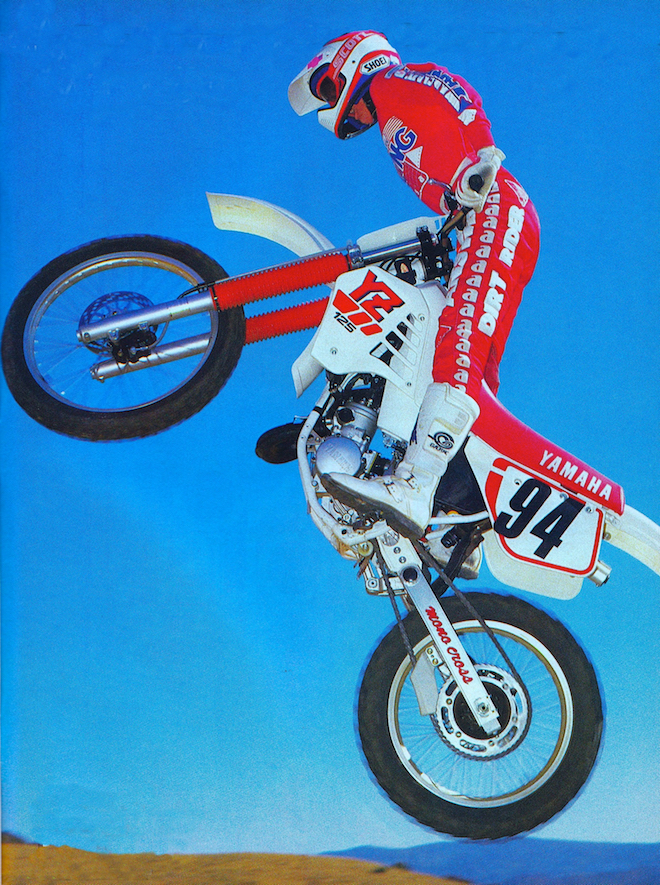

Up, up and away: With its meaty midrange blast, launching the YZ up and over tricky obstacles was a piece of cake in 1988. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider |

In the motor department, there were two major issues that needed addressing for ‘88 – top-end power and shifting. Since 1986, the YZ125 had been plenty fast, but the power was long on punch and short on breadth. It came on strong down low (extremely early for a 125) and hit very hard in the midrange, but threw out the anchor if revved. In an effort to coax a little more rev out of their 123cc case-reed mill Yamaha redesigned the cases to accommodate a larger reed-valve, redesigned the valve to mimic an FMF unit, streamlined the YPVS for less restriction and changed the ignition. A new pipe, new porting and a rebalanced flywheel further tried to free up the Y-Zed’s reluctance to sing the high note.

|

|

The Sultan of Snap: Since its introduction in 1986, the YZ’s 123cc case-reed mill had provided the most blast in the class. Strong off the bottom (particularly for a 125), brawny in the middle, and completely devoid of any top-end, the YZ was quicker than it was fast. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

In the shifting department, Yamaha took a two-pronged attack to rectify its notoriously poor action. First, they upgraded the clutch with an additional fiber plate, one more spring and a switch to needle bearings for the actuator. In the transmission, they increased the main shaft diameter by two millimeters and beefed up the gears for more durability.

|

|

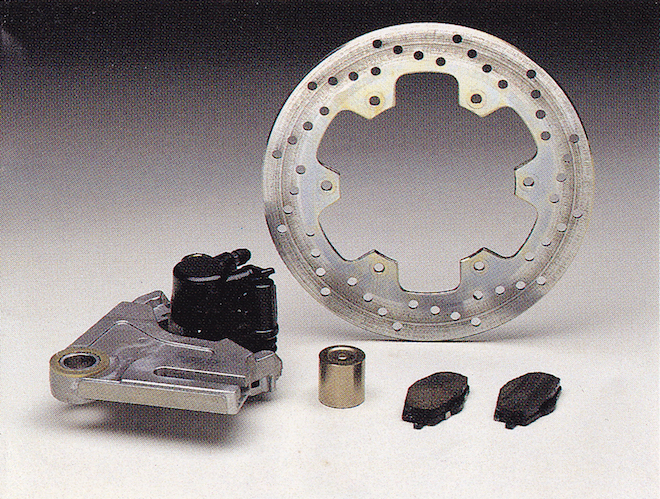

Another major improvement for 1988 was the addition of a rear disc brake for the first time. While far more powerful than the drum it replaced, its grabby engagement took some getting used to. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

Unfortunately, all of these motor upgrades did little to actually change the performance of the YZ. It remained the same hard-hitting low-to-mid motor it had been the previous two years. Low-end was particularly remarkable for a 125 and the little Yammer positively barked out of turns. It had the most low end and midrange in the class, but once again fell short when revved. If you nailed each shift perfectly and caught the next gear before the power flattened out it was brutally effective, but if you tried to stretch out that gear a second too far, the motor stopped pulling like you sucked a chipmunk into the airbox.

|

|

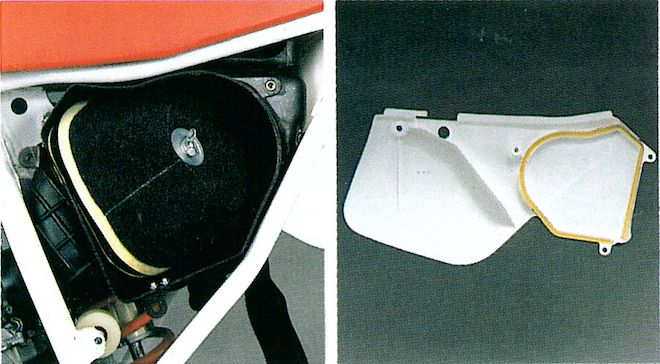

One nice feature on the ’88 YZ was this large side-access airbox. Similar to what KTM uses today, this design allowed for much easier servicing than the cramped competition. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

It was the ultimate burst motor and riders either loved or hated its punchy delivery. For those accustomed to a traditional 125, the YZ could be frustrating. Unlike the CR125R, which just kept pulling the longer you left it on, the YZ demanded a perfectly timed shift to keep it on the bubble. With its unorthodox powerband, the YZ actually took a more Open-bike style approach; keep it a gear tall, ride the torque curve, and slip in another cog before the motor stopped pulling. Of course, this could be frustrating as well, because the YZ’s transmission continued to be the worst in the class by a wide margin.

|

|

Another one of Yamaha’s hot prospects on the YZ125 in 1988 was La Porte, Indiana’s Mike LaRocco. LaRocco would win two 125 Supercross main events in ’88 and take his YZ to a solid seventh in the 125 National outdoor standings. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

The new transmission proved no more adept at changing gears than the old gearbox was. The new clutch worked well enough, but the gearbox itself refused to change gears under a load. Under power, it was virtually impossible to upshift or downshift without backing out of the throttle and feeding in some clutch. With each shift being so critical to making its narrow powerband work, keeping the YZ at full boil could be an exasperating experience. Nail each shift and keep her singing and the YZ could fly, muff one of those shifts though, and you would be left stomping on the gear shift and fanning the clutch as the competition roosted by.

|

|

The new 43mm Kayaba cartridge forks on the YZ offered 12” of travel and 18 adjustable compression settings (only the Suzuki RM offered adjustable rebound in 1988). They were plush and well controlled on small hits, but a bit too soft on mega-leaps. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

In the suspension department, the changes were much more successful. The new 43mm cartridge Kayaba forks worked roughly 900% better than the torture devices used on the ’87 YZ. They were plush on small hits and worked reasonably well on big impacts. There was none of the harshness that pounded the rider’s wrists in 1987 and much better control in the rough. Faster and heavier guys could bottom them out on mega leaps, but overall they were a vast improvement and on par with the competition.

|

|

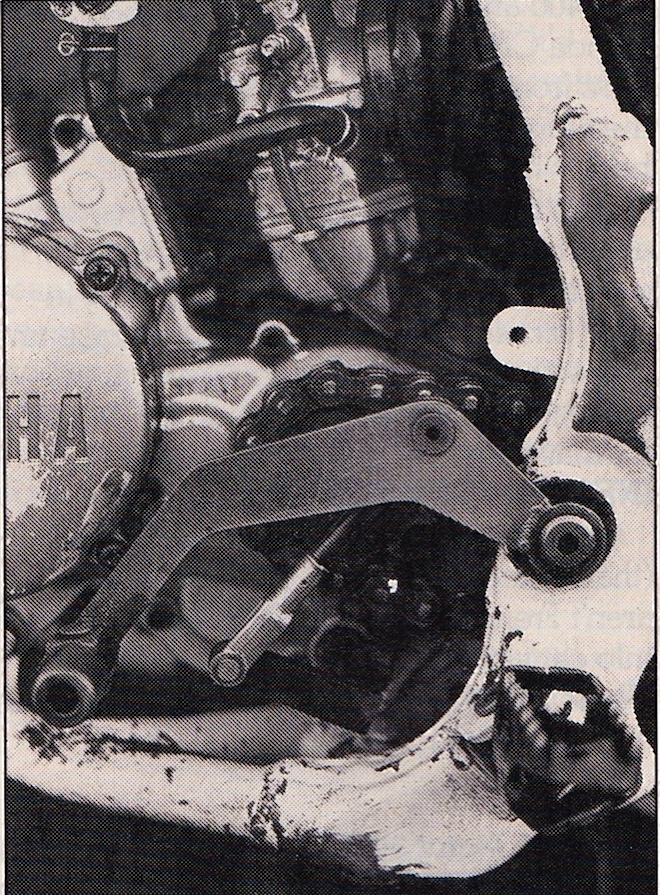

Gyro Gearloose: While the YZ’s lack of top-end could be frustrating, by far its biggest handicap was its recalcitrant shifting. The bike was virtually impossible to shift under power (I bent two shift shafts on my personal YZ125 by stomping on the damn shifter trying to catch the next cog) and notchy at all times. Thankfully, however, the clever folks at Race Tech came up with a solution for this malady. Their new shifter used a set of arms and linkages to relocate the pivot point back to the swingarm. This gave the rider a great deal more leverage and made a HUGE difference in shift performance (I used one on my personal YZ and the difference was incredible). Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

|

|

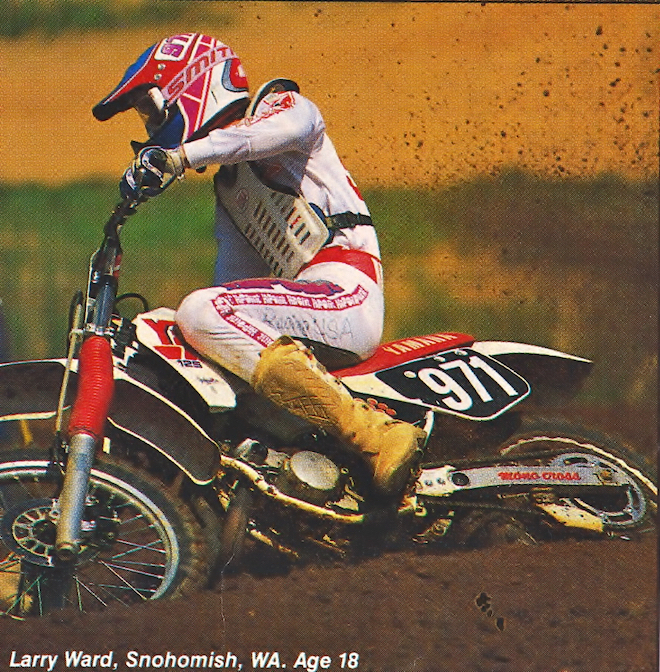

Snohomish, Washington’s Larry Ward was yet another young lion in Yamaha’s stable in 1988. His third overall at Southwick in ’88 would be his best finish on the white and red machines, before making the jump to team Honda for the ’89 season. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

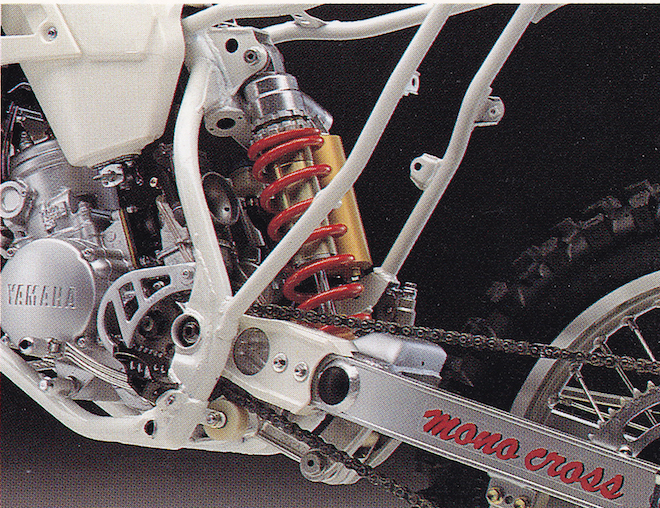

In the rear, Yamaha finally ditched their creative, but unloved Brake Actuated Suspension System for 1988. The BASS was supposed to improve tracking under braking, but most riders found the YZs actually worked better with the system disconnected. The new piggyback Kayaba shock also revised the compression adjustment by switching to a bleed-type adjuster from the pop-off valve of ’87. Both the swingarm and Monocross linkage remained largely unchanged for 1988.

|

|

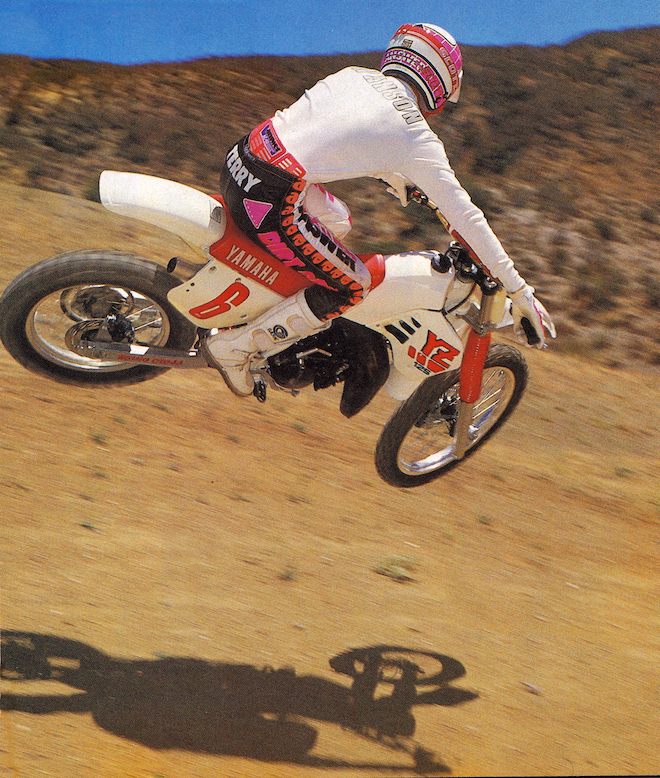

With its punchy motor, light weight and slim ergonomics, the YZ was a capable flyer. Yamaha ace Doug Dubach demonstrates the YZ’s flickability in 1988. |

|

|

Swedish knock-off: The Öhlins-inspired rear shock on the YZ125 was better at big hits than small chop. Stutter bumps and track chatter flummoxed its damping and the rear became very busy at speed. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

On the track, the new shock performed more or less the same as 1987. It was good at charging obstacles, but busy in off-throttle situations. If ridden aggressively, it did a good job of absorbing the track, but once you backed off, it got busy and unpredictable. On square-edged whoops or braking bumps, it was prone to kicking suddenly and never quite settled down. No amount of spinning dials ever got rid of this unsettling behavior and most riders found keeping their weight back and holding on for dear life was the best remedy.

|

|

The chassis of the ’88 YZ favored stability over razor sharpness. The front end was very light and prone to wheelies under acceleration, so care had to be taken to maintain your line under power. On the plus side, however, there was none of the heart-stopping headshake that made riding the Honda such a white-knuckle experience. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn |

In terms of handling, the YZ was a bit of a mixed bag. The inherent stability of the chassis was quite good, but the hop-o-matic shock could often make that a moot point. Once the shock was dialed, the YZ was as steady at speed as a bullet train. In the corners, the abrupt nature of the power and the YZ’s light front end made it difficult to always hit your intended line. Wheelies were common and the bike never felt as sure and planted as the scalpel-sharp Honda. With its slim layout and smooth bodywork, the YZ was easy to move around on and an able flier. Like most 125s, it felt very light in the air and on the ground and its handling shortcomings were not nearly as much of a handicap as they would have been on a heavier and more-powerful machine.

|

|

Two minor irritations on the ’88 YZ were its lack of a removable rear subframe and Yamaha’s usage of a slab of concrete for its chain buffer. The subframe omission was puzzling when three of the YZ’s competitors offered this time and hassle-saving feature, while the chain buffer was perhaps a bit more forgivable. On the plus side, it was unbelievably durable and likely to outlast every other part on the bike. On the negative side, the incessant clattering the chain made when slapping up against this hunk of Adamantium was more annoying than a Red Bull-fueled five-year-old with a drum set. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

In the braking department, the YZ made major strides in 1988 by finally stepping up to a disc in the rear. Although extremely cobby looking, the new 220mm disc offered a lot of power. Its main weakness was its grabby feel, which took a lot of getting used to. Those accustomed to the previous drum or Honda’s excellent rear stopper were likely to find themselves stalling the YZ several times before becoming familiar with the YZ’s light-switch engagement. Up front, the disc size was increased 10mm for 1988 to a total of 230mm. This gave the bike more bite, but again, not as much feel as the well-modulated dual-piston units found on the CR. Overall, they got the job done, but lacked the feel of the best binders in the class.

|

|

While the YZ was an able flier, the mismatched suspension (soft forks and a stiff shock) made landings a less than stellar experience. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider |

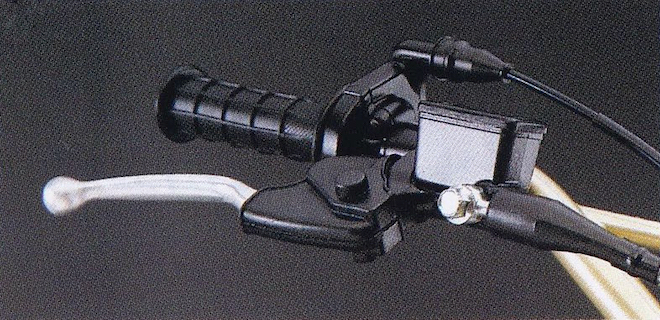

In the detailing department, the YZ was pretty typical for the time. Things like the butter-soft steel bars, rock-hard grips, brittle levers and cheesy fasteners were all par-for-the-course in the mid-eighties. The lack of a removable subframe (the YZ made due with a removable bar on one side) was less forgivable, with Honda, KTM and Kawasaki all offering them by 1988. Probably the most annoying feature, however, was the Yamaha’s chain buffer, which was as hard as a rock and noisy enough to be heard over the exhaust. That tell-tale clackity-clack became an unfortunate YZ trademark in the mid-eighties.

|

|

New bars for 1988 improved the YZ’s notoriously uncomfortable bar bend, but did nothing for its palm-chewing grips. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

|

In 1988, the Suzuki and Yamaha were at opposite ends of the powerband spectrum. The RM was a top-end only screamer and the YZ was a low-to-mid torquer. Photo Credit: Moto Revue |

In the plus column were the YZ’s slim ergonomics, comfortable seat, easy-to-access filter and excellent overall reliability. Even with its cranky transmission, nothing in the motor broke and the YZ actually became a popular choice for off-road enthusiasts looking for a 125 that could take major punishment. The lack of top-end hurt it in the desert, but the excellent bottom-end torque and plush forks were perfect for woods work. It was a very versatile bike that was fun to ride and durable.

|

|

In 1988, the YZ’s prodigious midrange blast literally launched it out of corners. As long as you could ride the razor’s edge of its narrow powerband, it was as fast as anything in its class. Photo Credit: Tom Webb |

In 1988, Yamaha produced a polarizing 125. Its potent low-to-mid motor made it both unique and more adept off road than your typical 125, but its stubborn gearbox and precipitous drop off in top end made it a hard bike to ride fast. Unlike the typical 125, the YZ was no pin-it-to-the-stops and hang on type of bike. It was a machine that required skill and careful gear selection to make work. Get it right and you flew; get it wrong, and you were left sucking wind as the competition blew by. For those who made it work, the YZ was fast and fun; for those who couldn’t, the YZ was frustrating. For most 125 hot shoes, the Honda CR125 was a better choice, but for those who enjoyed its distinctive flavor, the 1988 YZ125 could be a potent motocross weapon.

|

|

A major improvement from the dark days of the early eighties, the 1988 YZ125 was a solid contender, but no all-star. Its hard-hitting motor made it fun to ride, but its narrow power spread, stubborn shifting and busy shock kept it from challenging the best bikes in the class. |

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com