For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at one of the last of Suzuki’s Open class two-stroke racers, the 1983 RM500.

|

| Never the fastest Open class bikes available, the big RMs were always more about finesse than brute force. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

Suzuki has a bit of a checkered history in the Open class. Today, the RM-Z450 is a bit long in the tooth (not counting the soon-to-arrive redesigned 2018), but it is still one of the most successful machines on the AMA circuit. In spite of its nearly decade-old design, it has continued to rack up victories and championships based on its excellent handling and solid overall performance. The current RM-Z is not sexy, but it is a great base from which to build a championship-winning racer.

|

| In order to turn the RM465 into the RM500, Suzuki bored out the cylinder 2.5mm and bolted on a new higher-compression head. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

In the early days of motocross in America, however, that was certainly not the case. Suzuki’s initial entry into the Open class was nothing short of an absolute disaster. Built from 1971 through 1975, the original TM400 Cyclone was an under-suspended, over-powered and ill-handling mess of a motorcycle. The Cyclone started off terrifying and got only marginally less so with each model update. By 1975, most of its demons had been exorcised, but it continued to be too heavy and poor handling for any serious racing applications.

|

| The key to Suzuki’s early eighties motocross success was the design of their innovative rear suspension system. Coined “Full Floater” for its unique dual-linkage design that allowed the shock to “float” independently at both the top and bottom, this system dominated motocross suspension from 1981 until its retirement in 1986. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

In 1976, Suzuki finally turned its Open class fortunes around with the introduction of their first big-bore RM, the awesome RM370A. The new RM370 was everything the portly TM400 had not been. It was light, fast, and well suspended. Its new long-travel suspension punched out over eight inches of travel front and rear and its new “Power-Reed” motor was broad and torquey. It was an excellent Open class racer and by far the best big-bore machine ever offered from Suzuki.

|

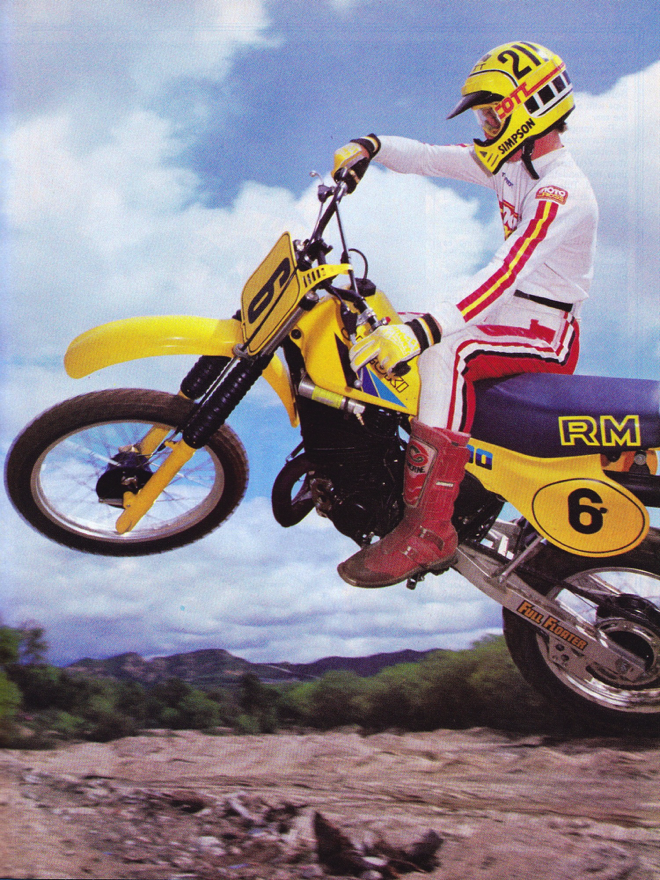

| In 1983, the RM500 offered a solid package for novices, but most fast riders would have preferred more top-end power. Photo Credit: MOTOcross Magazine |

During the rest of the late seventies, Suzuki capitalized on its reputation by building solid and competitive alternatives to the established European Open class offerings. While not as dominating in the big-bore classes as the smaller divisions, Suzuki continued to be at the front with their RM370 and later, RM400. The big RMs were not the fastest bikes in the class, but they handled well and offered class-leading suspension.

|

| In 1983, the 500 class was alive and well with a full stable of entries from Europe and Japan looking to claim your hard-earned dollars. Photo Credit: Cycle Guide |

In 1981, Suzuki further increased that suspension advantage by introducing their first single-shock rear suspension system, the Full Floater. This amazing suspension system consisted of a set of struts and linkages that compressed the shock both from the bottom and the top simultaneously. This allowed the shock to “float” (hence the name, “Full Floater”) independently of what the rest of the bike was doing and react more precisely to the terrain. The Full Floater was complex, but did an amazing job of taming track obstacles. The new RM465 proved once again to be less powerful than its rivals, but its amazing rear suspension made it a very competitive Open class mount in spite of this shortcoming.

|

| Mellow Yellow: The new ‘83 RM500 motor offered a little more low-end torque than the old RM465, but not a lot more outright power. In spite of the increased displacement, it continued to offer the least potent power package in the class. Photo Credit: Le Big |

By 1983, the Open class was reaching the zenith of a displacement war that had been escalating since the late seventies. Once mid-sized bikes like the YZ360 had morphed into big-bore monsters like the YZ490 in the pursuit of ever more power. For 1983, Suzuki joined this game of one-upsmanship by increasing the displacement of their Open class RM from 464cc to a full 492cc. Redubbed the RM500, Suzuki’s Open class entry was now on par in displacement with the big bores from Honda, Yamaha and Kawasaki.

|

| With its light 227-pound dry weight, mellow motor and excellent rear suspension the RM500 was easier to ride than most of its big bore competition. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

In the transition from 465 to 500, most of the changes to the RM were relatively minor. Cosmetically, the two bikes looked virtually identical, with the only differences being new decals, a blue seat (from black in ‘82) and yellow paint on the lower fork stanchions. Mechanically, the bike was also only slightly updated from ’82. The Full Floater rear suspension maintained the same basic design it had used since 1981, but new alloy struts replaced the steel struts used previously. A new shock was also added that featured adjustments for compression and rebound damping and a redesigned reservoir for improved cooling. The overall wheelbase was lengthened 10mm and a new fork offset increased trail by 1mm. New forks maintained the 43mm size of ’82, but added adjustable compression damping for the first time. Of all the changes of ‘83, maybe the most welcome was the addition of a dual-leading-shoe binder for the front brake. This unit addressed one of the RM’s most glaring faults and brought it almost up-to-par with its competitors in the braking department.

|

| Grim vergasser: While the RM’s relative lack of horsepower was an issue, by far its biggest motor problem was its abysmal carburation. The 38mm flat-slide Mikuni came jetted for Mars and made the bike a blubbering and smoke-belching mess in stock condition. Even worse, it offered no idle circuit and just keeping the big Zook running in slow sections was an exercise in frustration. Photo Credit: Le Big |

In 1982, the RM465 motor had been one of the least powerful in the class. It offered a strong midrange burst, but not much else. In order to beef up its delivery, Suzuki took the time-honored American Hot Rod route and stuck a bigger piston in it for 1983. To accommodate the bigger slug, the engineers took the old RM465 cylinder and bored it out an additional 2.5mm. This yielded a 28cc increase in displacement without altering the motor’s stroke. To go with the new cylinder, a new head was spec’d that boosted compression slightly and a new flywheel was bolted on that offered seven percent more flywheel inertia for a smoother delivery. The cylinder retained the reed-valve intake of ’82 and drew fuel through a 38mm Mikuni flat-slide carburetor and the most asininely complicated airbox this side of a Rubik’s Cube. In the bottom end, the new RM500 motor retained the four-speed transmission of 1982, but new ratios were installed to better suit the beefed-up powerband.

|

| With its absurdly soft front forks, nose down landings were not advisable on the ’83 RM500. Photo Credit: MOTOcross |

On the track, the new 492cc power plant proved only slightly more potent than the old 464cc version. The bump in displacement yielded slightly more low-end thrust, but it was certainly not in the same league as most of the other big bore monsters in the class. Once cleaned out (and this took a while), the RM pulled through a decent midrange hit, before falling off a cliff as the powerband climbed into the top-end. It was all midrange, with little usable thrust at the extremes. Hurting matters was the RM’s stock jetting, which was so out of the ballpark that the bike would load up coming into slow corners and belch smoke like a mosquito fogger once you opened the throttle on exit. In stock condition, the RM blubbered and coughed constantly as the motor tried to choke on its fuel charge. Once leaned out, it was reasonably fast, but still no match for its rivals. It lacked the blast of the CR and the long pull of the Yamaha. It was easier to ride than the absurdly explosive Kawasaki, but only novices were going to be satisfied with its relative lack of thrust.

|

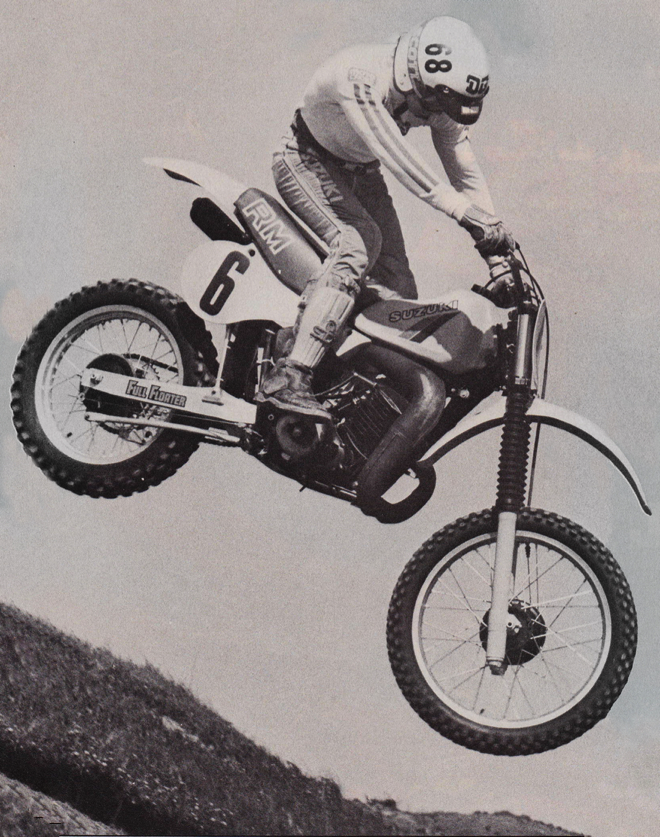

| For 1983, Suzuki added adjustable compression damping for the first time to the RM’s front suspension. There were eight adjustable compression settings and 11.2 inches of travel offered by its 43mm KYB sliders. While competitive in features and size, their performance was less than ideal. They were too softly sprung and underdamped for the weight and power of the big Suzuki. In stock condition, they hung down in the stroke and greeted any reasonably sized jump with a metal-to-metal clank upon landing. Photo Credit: Le Big |

In the suspension department, the RM500 was a case of good news and bad news. Up front, the big Suzi offered 11.2 inches of travel from its 43mm KYB forks. These units were adjustable for air-pressure and compression damping, but offered no adjustments for rebound. Out back, the RM offered a full 12.9 inches of travel from its Full Floater rear with four settings for compression and rebound damping available. On most bikes, the travel front and rear is typically pretty similar, but on the RM, there was decidedly more movement in the rear than at the front. The front forks were also much softer than the rear and it gave the RM a decidedly “stinkbug” stance.

|

| Shredder: At speed, the RM500 could be a bit of a handful, but in the turns, it had few peers. With its soft forks and steep geometry, it could turn under all but Honda’s razor-sharp CR480R. Photo credit: Dirt Bike |

In action, the KYB forks offered pretty dismal performance. Even by the admittedly poor standards of the time, they were pretty grim. Both the spring rate and damping characteristics were too soft for motocross use and any reasonably sized jump made them bottom out with a resounding THUD! Changing to a heavier weight oil and adding preload spacers to the springs helped somewhat, but their action defied most easy fixes. The new compression damping adjuster made no appreciable difference in performance and MXA even went as far as hacksawing it out of the forks in search of improved action. In truth, none of the stock 500 forks of 1983 were really very good, but the RM’s pathetic performance certainly did itself no favors in this area.

|

| In the rear, the outlook was much rosier for RM500 owners in 1983. The Full Floater rear was well sprung and offered the best damping in the class. Unlike the marshmallow front forks, the rear was set up on the stiff side and the faster you went, the better it worked. Photo Credit: Le Big |

Out back, the outlook was much better, with the RM offering the best performance in the class. The Full Floater was sprung well and offered far better control than most of the other 500 class offerings. On an Open bike, suspension is critical and the RM had a solid advantage in this category (at least in the rear). It took whoops and jumps with equal aplomb, but it could feel a bit too stiff for some of lesser skill. If you rode aggressively, it worked well, but if you backed off, it only exacerbated the bikes imbalance front-to-rear.

|

| In 1983, the 500 landscape was full of a myriad of choices for potential buyers. For fast guys, the awesome CR480R was the obvious choice, but for those of more modest talents, the mellower RM500 was a viable racing option. Photo Credit: Ron Lawson |

That imbalance also played a major role in the bikes handling. The soft forks allowed it to hunker down in slow corners and the stinkbug stance put a lot of weight on the front wheel. In slow turns, this worked to the bike’s advantage and the RM carved a nice tight line. At speed, however, the bike became an absolute handful. Headshake was violent and the bike was pretty terrifying until the forks were stiffened and the bike was brought into better balance. Once the chassis was leveled out, the RM still had a nasty twitch, but at least it was no longer bordering on suicidal. Aerial manners were good for a big bike and the RM’s light 227-pound weight and good ergonomics made it easier to manage than many big brutes. Overall, it was a good handler, with sharp turning and a penchant for meandering at speed.

|

| One badly needed change for 1983 was the addition of a dual-leading-shoe front binder for the RM. The state-of-the-art in drum technology at the time, this linkage design offered far more power than the single-cam designs it replaced. While an improvement, the new brake still proved less powerful than the units found on its Japanese competitors. Photo Credit: Le Big |

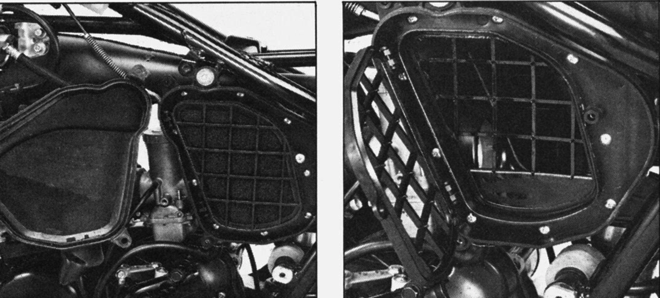

In the details department, the RM was a good, but not great bike in 1983. The new motor proved reliable overall, but some premature ring wear and its ridiculously bad jetting made life with it a pain at times. The four-speed gearbox also limited its appeal for anything other than MX use. The airbox on the RM was an insanely overcomplicated mess that buried the filters in the motocross equivalent of Fort Knox. Getting to the filters was a marathon that required removing two side panels, two airbox covers, two cages and about a dozen assorted screws and bolts, all of them of different sizes and types. Ugh.

|

| You could probably rebuild the RM’s motor faster than service its crazy dual-element filter system. Photo Credit: Cycle World Magazine |

On the braking front, the new dual-leading-shoe front binder improved power, but it was still not as good as the units found on the competition. Overall power was mediocre and its action was grabby. The cable running to it was also very exposed and easily damaged. Compared to the excellent drums found on the CR and YZ and the trick disc on the KX, the RM’s front brake seemed like a half-hearted effort. In the rear, the drum was more competitive, but the action was also grabby and the shoes tended to wear very quickly.

|

| The Suzuki RM500 was a bit of a throwback in 1983. It harkened back to a time when Open bikes were not about eye-popping horsepower and monster hits. Its power was mellow and its hit wasn’t massive. It needed some serious jetting help and some major fork massaging, but with those two things sorted, it was a very competitive Open class mount. |

Overall, the 1983 RM500 proved to be a decent, if not world-beating Open class machine. It was not as fast as the CR, KX or YZ, but it did offer light weight, sharp turning and excellent rear suspension. The relative lack of power was a handicap for pros and fast intermediates, but its mellow power was probably a plus for those intimidated by the sudden burst of the other machines. With an upgrade to the forks and some serious jetting work, it became a competitive 500 mount. It was not as aggressive as Honda’s awesome CR480R, but for many average riders, the mellow yellow RM made a better choice.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com