For this edition of Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at Yamaha’s all-new YZ250E for 1978.

|

|

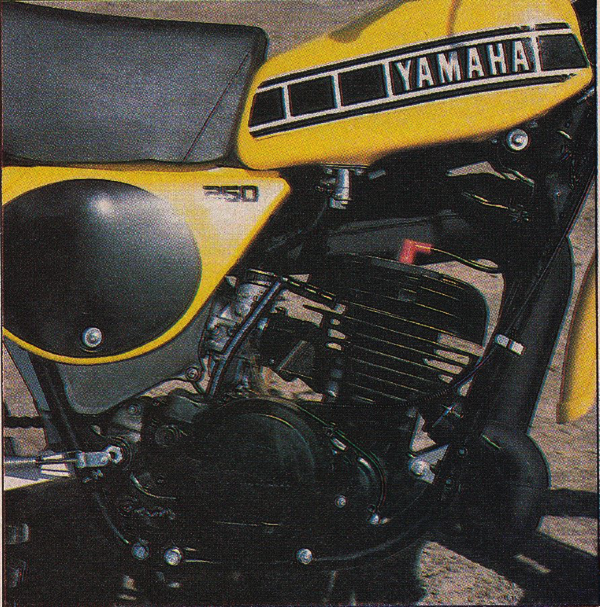

While the new 1978 YZ250E looked very much like a warmed-over 1977 “D” model, it was actually a very different machine. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

In 1973, Yamaha introduced the world to the wonders of long-travel suspension. Making its debut on Håkan Andersson’s works YZ637 factory racer, the first monoshock offered roughly twice the travel of anything else available at the time. By 1975, that technology had made its way to the common man in the form of Yamaha’s first production monoshocks, the YZ250B and YZ360B. The new YZs were exotic, expert-oriented, and in the case of the YZ250, nearly twice the price of a CR250M Elsinore. The new machines sweat trickness and kickstarted a suspension revolution that would come to define late-seventies motocross.

|

|

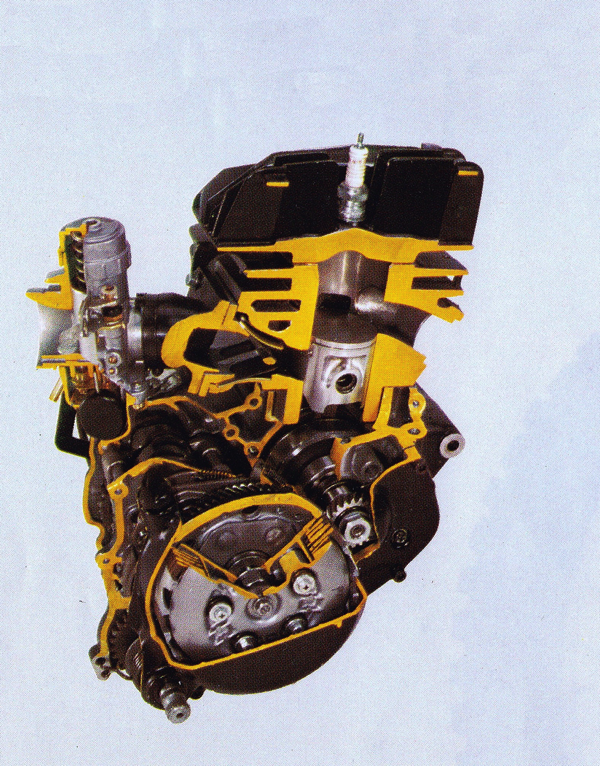

One of the most significant changes on the ’78 YZ250E was its all-new motor. Lighter and more compact in nearly every dimension, the new mill maintained the bore and stroke of the old power plant, but added more aggressive porting and a new close-ratio six-speed transmission. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

By 1978, the suspension war was in full swing and every manufacturer had 250 machines creeping up on a full foot of travel. In the short span of four years, suspension travel had nearly tripled across the board. While this improved the bike’s ability to tackle rough terrain, it brought with it its own set of engineering issues. Chief among these was chassis flex. As the manufacturers began to increase travel, they quickly found that the frame technology of the time was having a hard time keeping up with the increased load. Forks flexed, swingarms twisted, and chains derailed as the engineers struggled to find the best combinations of materials, design, and execution.

|

|

An all-new chromoly (or chrome-moly as it was called in 1978) frame added strength and trimmed weight for ’78. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

For Yamaha, this was even more complicated, as their new rear suspension design brought with it a unique set of challenges. Unlike Kawasaki, Honda and Suzuki, who chose to simply angle their existing dual-shock systems forward in order to achieve more travel, Yamaha had gone with a totally original suspension system. Based on a design from Belgian engineer Lucien Tilkens, the original Yamaha monoshock system consisted of a large single shock, laid down the length of the frame backbone and attached to a triangulated rear swingarm. This configuration allowed the original monoshock to produce roughly twice the travel of the traditionally-placed dual shock systems of its time. While effective at increasing travel, Tilkens’ design did have its drawbacks. By placing the shock deep inside the bodywork, the damper tended to run very hot and early monoshocks suffered from severe fade. The placement of the shock so high on the chassis also gave the bike a top-heavy feel and slightly odd turning manners.

In addition to these quirks, early mono’s also suffered from a nasty habit of kicking in the rough. Under power, they worked well enough, but back off in the bumps and the rear end was likely to try and buck you off. Something about the YZ’s geometry and unique suspension design seemed to bring this behavior about. While later refinements would minimize this trait, “Yama-hop” would never be fully exorcised from the pre-linkage Yamaha monoshock machines.

|

|

The Golden Boy: The personality of the new YZ250E was definitely skewed more towards the aggressive end of the spectrum. Fast guys like Broc Glover (pictured) could make devastating use of its potential, but those of lesser talent tended find its high-strung personality frustrating. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike Magazine |

For 1978, Yamaha looked to address these and many other issues with an all-new YZ250. While the new bike looked very similar to the outgoing YZ250D, the new E model was completely new from the ground up. A new frame, suspension and motor highlighted the YZ250E and set it apart from its predecessor. In truth, about the only thing that was not totally new on the E model was the bodywork, which carried over largely unchanged from 1977.

|

|

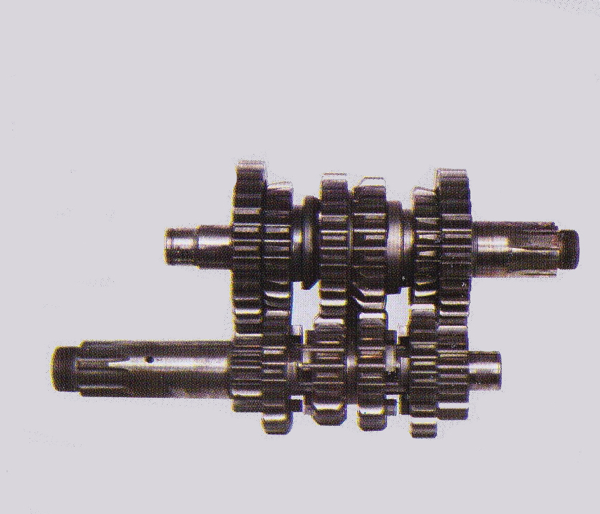

Six-pack: A new six-speed transmission for 1978 tightened up ratios and added an additional gear to the YZ’s repertoire. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

In redesigning the YZ250 for 1978, one of the major goals of the Yamaha engineers was to improve its wayward handling. While some of the bike’s handling peccadillos were not going to be totally eliminated without a total redesign of the Monocross system, Yamaha reasoned most of them could be mitigated by beefing up the existing design. In order to accomplish this, Yamaha spec’d an all-new frame for the YZ250E. The new chassis maintained the same basic configuration of ’77, but added strength and trimmed weight for ‘78. To accomplish this, they upgraded the frame from heavy and flexy carbon-steel to light and strong chromoly steel. By switching to chromoly, the engineers were able to reduce the frame wall thickness by .2mm across the board and knock a full five pounds off the weight of the chassis.

|

|

Like a candle in the wind: Although handsome, the stock tank decals on the YZ were not long for this world. Photo Credit; Motocross Action |

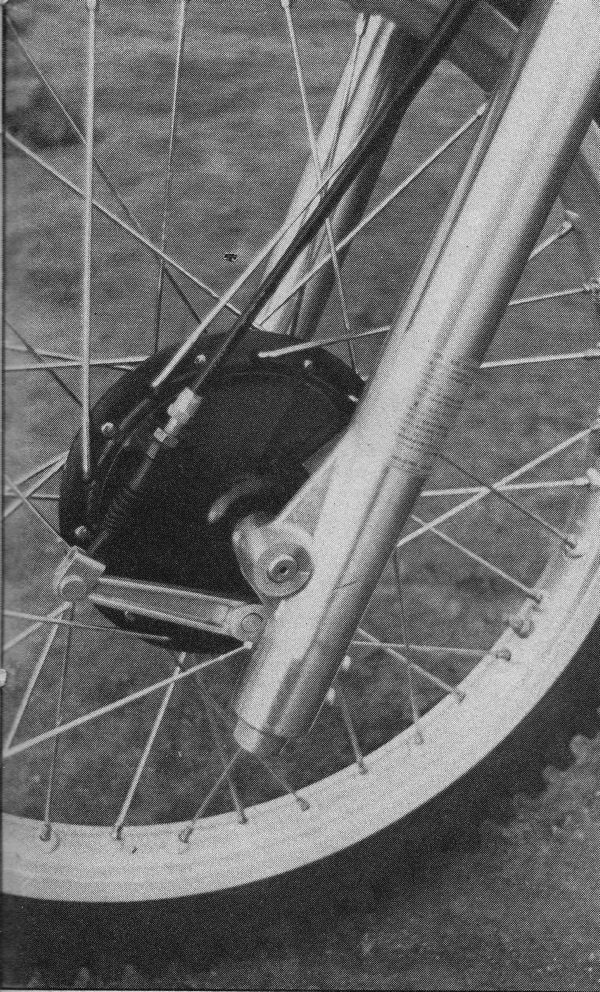

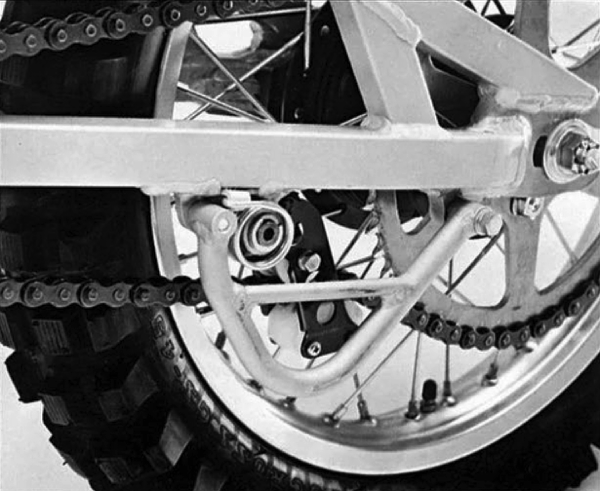

Paired with new the chromoly frame was a redesigned swingarm for the Monocross rear suspension. In 1977, one of the hot setups had been to swap the flimsy steel stock swingarm for a beefy alloy unit. For 1978, Yamaha made this upgrade standard equipment by bolting on a sano unit that looked to have been taken directly off Bob Hannah’s works racer. The new design maintained the triangular configuration in use since 1975, but swapped out the flexy mild steel for ultra-rigid aluminum. With big welds and massive tubes, the new swingarm was far less prone to flex than the old design and combined with the new stronger frame, went a long way toward sorting the Yamaha’s unruly rear-end habits.

|

|

Pin it to win it: For 1978, Yamaha actually looked to their road race line for power inspiration. Porting on the new YZ250E closely mimicked that of the TZ250 pavement racer and resulted in a high-strung and top-end-focused power curve. Photo Credit: Cycle World |

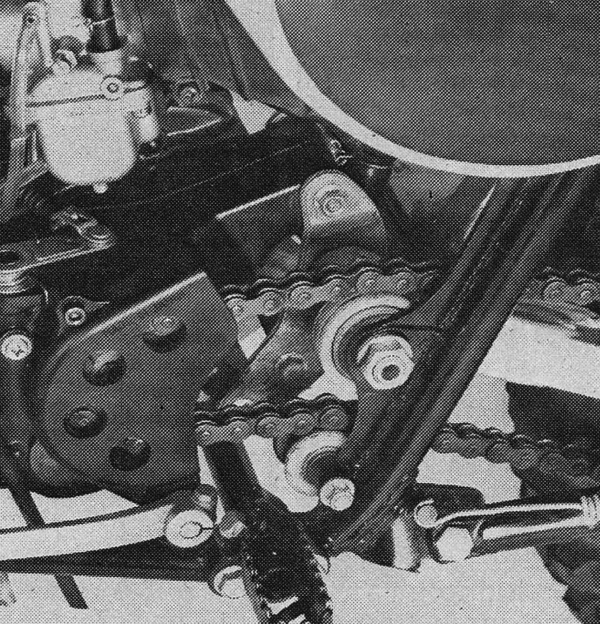

In the motor department, Yamaha went all-out toward upping performance in 1978. An all-new motor was spec’d that both increased power and saved weight. The new design maintained the internal dimensions of ’77, but shared little else with the old design. The new mill was lighter, shorter and slimmer, offering a lower profile and a two-pound weight savings. In an effort to reduce chain-related issues, the countershaft was also moved 15mm closer to the swingarm pivot to reduce the reliance on chain tensioners and help prevent derailments caused by the bike’s extreme suspension travel.

|

|

One major upgrade on the new YZ-E was a switch from flexy carbon steel to ultra-rigid aluminum for the rear swingarm. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

|

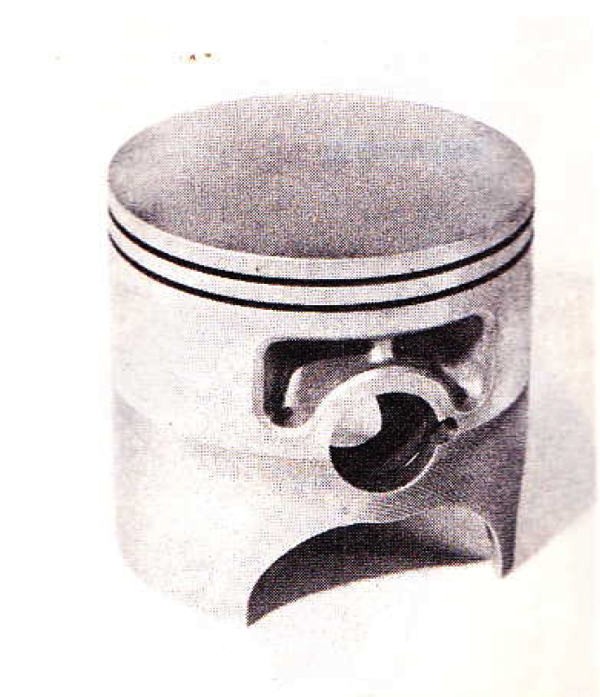

A new piston for 1978 added an additional ring and lubrication channels for increased durability. Photo Credit: Motorcyclist |

In an effort to boost power, Yamaha designed an all-new top-end for the YZ250E. The new cylinder and head retained the air-cooling and overall displacement of ’77, but offered more aggressive porting specs. The new head was also reshaped to offer a cleaner burn and a new two-ring piston (up from a single ring in ’77) was slipped in to increase durability. On the intake side, Yamaha retained the “Torque Induction” reed-valve configuration it had used since ’72, but added a 10mm larger reed-valve and 2mm larger Mikuni carburetor for increased flow. Finishing off the motor package was an all-new six-speed transmission (up from five speeds in ’77), hotter ignition (also lighter for ’78) and a revised exhaust that offered better sealing (two sealing rings at the header instead of one) for increased performance.

|

|

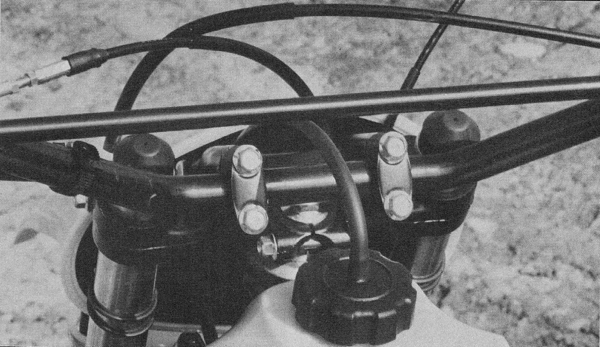

In 1978, having externally adjustable damping was quite a novelty. On the YZ, a small screw located under the tank allowed riders to select from 13 available damping settings. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

|

For 1978, Yamaha added an additional 20mm of internal overlap to the YZ-E’s 38mm forks. This was done to reduce flex and prevent binding under heavy loads. Interestingly, instead of casting all-new lower legs, Yamaha chose to just add a second drain plug below the first (seen above at the bottom of the leg) to accommodate the new internals. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike Magazine |

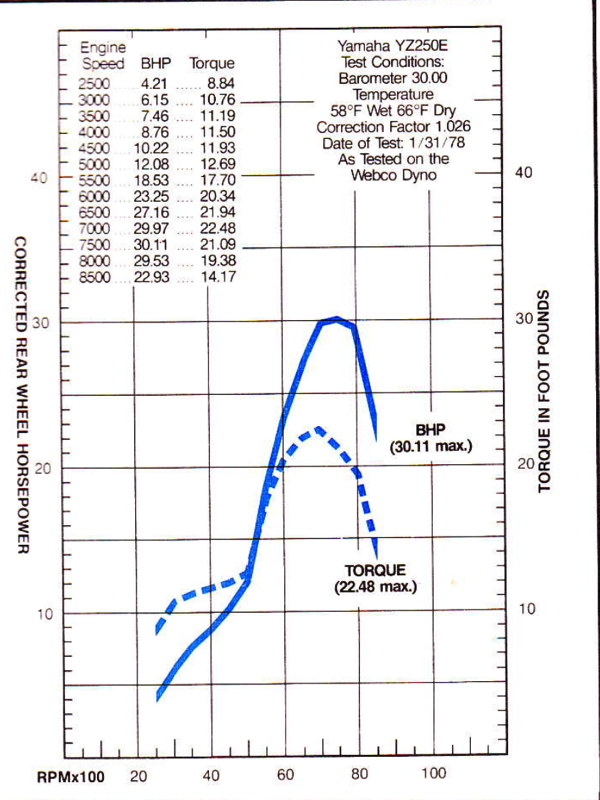

On the track, the new YZ-E motor proved faster, but not necessarily better than before. On paper, it provided more power, but that power was harder to manage. Off the bottom, there was not a lot of torque and the bike needed to be ridden like a big 125. If you shifted too soon and let it fall off the pipe, then a downshift and healthy dose of clutch were required to get it back up to speed. Once in the midrange, however, the new bike pulled strongly and kept pulling well past the point where the old motor had flattened out. It was tricky to get going at times and far harder to get hooked up on slick surfaces, but faster when traction was present. For pros, this was a welcome trade off, but novices could be frustrated by its peaky power and explosive hit.

|

|

With its top-heavy feel and slack steering geometry, the ’78 YZ250E was no shredder. In turns, it was best to come in hot and steer with the rear, as opposed to trying to carve a tight inside line. Photo Credit: Motorcyclist Magazine |

For those interested in doing more than racing the YZ, the new six-speed trans added versatility, but action of the cogbox continued to be poor. Selecting gears required a strong left boot and shifting under power was all but impossible without backing out of the throttle and feeding in some clutch. A new 10mm longer shifter for ’78 did improve action slightly by providing a bit more leverage, but the YZ continued to offer the most cranky gearbox in the class.

|

|

This dyno curve gives you a good look at just how abrupt the new YZ’s power was. From 5000 to 7000 rpm, it jumped from 12 horsepower to nearly 30. The new mill did provide a full two horsepower more than ’77, but that performance came at the cost of some ridability. Photo Credit: Cycle Magazine |

On the suspension front, Yamaha chose to refine, rather than completely redesign for 1978. The new YZ-E retained the same basic suspension layout of the D model, but made several important changes to improve performance. Up front, a set of 38mm Kayaba forks offered 9.8 inches of travel to go with its air/oil adjustability. While air could be added or subtracted via a Schrader valve to fine-tune performance (air pressure acted as a supplement to the coil springs, not a replacement as in modern air forks), there was no external adjustment for damping. For 1978, the only major change to the forks was the addition of 20mm of internal fork overlap. This small change was made to lessen binding in the front under a load and prevent the fork from locking when topping out.

|

|

One of the major problems facing early long-travel suspension designs was how to keep the chain from derailing as the suspension moved through its arc. Engineers had yet to work out the importance of having the countershaft directly adjacent to the swingarm pivot and instead relied on a complex combination of rollers and tensioners to keep the chain from going slack. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

|

Unfortunately, this Rube Goldberg approach to chain tension put the parts involved under tremendous stress and broken chain rollers were a common occurrence on the YZ-E. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike Magazine |

|

|

The new YZ250E power plant was fast, but demanding. There was very little torque off idle and a prodigious hit as it climbed into the midrange. While the new six-speed transmission aided versatility, it continued to be the most-stubborn cogbox in the class. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

Out back, Yamaha spec’d a new damper to go with its new works-style alloy swingarm. The revised shock maintained the DeCarbon design of 1977, but added a new super-slick coating for the bushings and an extra 4mm of shaft travel. Adjustability remained an advantage of the DeCarbon damper and the new YZ-E offered 13 available settings for damping to go with its 9.8 inches of travel.

|

|

In 1978, the YZ-E’s 38mm Kayaba forks were the best units to be found in the 250 class. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

|

Paging Ricky Carmichael: In 1978, swayed-back bar mounts were a thing. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike Magazine |

In terms of performance, the forks and shock were improved, but not night-and-day better than ‘77. The monoshock was plush, well-damped and highly adjustable, but still prone to the fade that had plagued mono’s since their introduction. Tucked away under the tank and away from any cooling air, the stock shock heated up quickly and lost damping performance in short order. Once hot, that nicely controlled action went out the door and it was back to Yama-hop-ville.

|

|

Ribbed for your pleasure: In 1978, these sano dogleg levers with finger notches molded in were very trick. Photo Credit: Motorcyclist Magazine |

|

|

In 1978, Bob Hannah was at the peak of his powers and railed a works version of the YZ250E to the AMA 250 National and 250 Supercross titles. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

Up front, the 38mm KYB forks were more successful and offered the best performance in the class. The added 20mm of internal overlap reduced binding and they provided plush and well-controlled action. For really fast guys, stiffer springs might be in order, but for most riders they required little more than fine tuning with the oil level and air pressure.

|

|

The new works-style alloy swingarm for ’78 addressed some of the monoshock’s issues, but it did not cure all of them. Without an external oil reservoir, it continued to be prone to premature fading, and the infamous “Yama-swap” was lessened, but not exorcised entirely. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

On the handling front, the new YZ was a solid improvement over its doppelganger predecessor. At 228 pounds, it was nine pounds lighter than the ’77, but still the heaviest bike in the class. The new stiffer chassis offered a more precise feel and improved turning over previous YZs, but the bike was still no shredder. Front wheel traction was not particularly exceptional and the bike tended to push the front end going into turns. This understeer at turn-in could be disconcerting to those unaccustomed to the YZ’s unique handling feel and jumping on it off of another machine took a bit of adjustment.

|

|

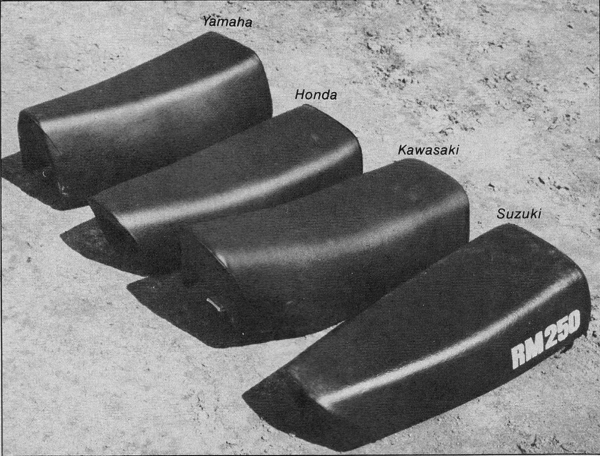

In the seventies, half of a bike’s suspension was its seat. At a whopping seven inches tall, the YZ-E’s seat was the king of the Barcaloungers in 1978. Photo Credit: Cycle World |

Where the new sturdy frame and beefy swingarm made the biggest handling difference was in the rough. There, the bike exhibited much less of the wandering and wallowing feel of the old machine. With a fresh shock and the power on, the YZ held straight and true and large whoops were taken in stride. If you chopped the throttle, however, the rear end could still do its patented side-to-side swap on occasion. It was less likely than in the past, but still a part of the YZ’s inherent DNA. Overall, it was better, but still very much a monoshock Yamaha.

|

|

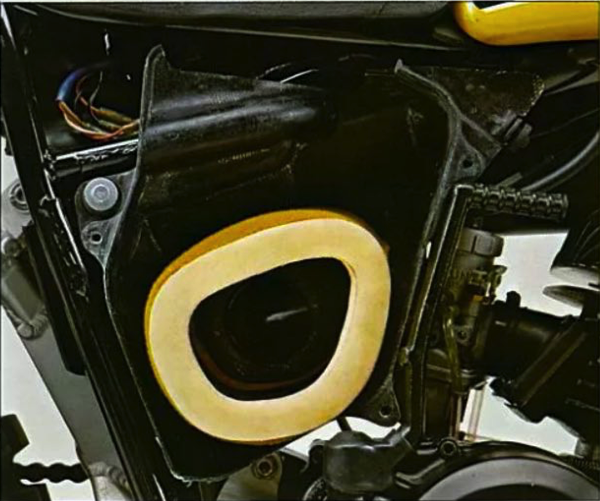

One major weak spot with the ’78 YZ was its porous stock airbox. Without a swap to an aftermarket filter and a bucket of grease, it was sure to suck dirt and ruin your top-end in short order. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

In the details department, the YZ was a bit of a mixed bag in 1978. On the plus side, it offered by far the coolest levers in moto (with sweet finger detents molded into the clutch and front brake controls), a very trick works-style alloy swingarm and strong brakes (although not full floating in the rear). On the negative side were its ejecto-matic stock decals (take a picture, they won’t make it past the first ride), porous stock airbox (buy a Phase-2 and learn to love grease, or stock up on spare cylinders), cranky shifting (a John Deer tractor shifted better), quirky handling (keep your weight back and learn to steer with the rear), and penchant for eating chain rollers (best to purchase them in bulk).

|

|

In 1978, Yamaha dialed up some major changes for their deuce-and-a-half racer. Lighter, faster, stronger and more aggressive, it was a pro-oriented bike that required talent to make the most of its potential. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

Overall, the new YZ250E was better in some ways and a step back in others. It was lighter, faster and better suspended, but also more demanding. Its hard-hitting motor and unique chassis were lethal to the competition in the right hands, but it took a certain amount of skill to extract that performance. If you were up to the challenge, it was literally capable of winning a National in near-stock condition, but if you were more mortal, it was just as likely to be a frustrating experience.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com