What happens when the can’t-miss kid misses?

“People used to say that he was going to be the next Bob Hannah because he was in Palmdale and he used to ride all those desert tracks that Hannah grew up on,” said Mike Chavez, who used to wrench for him while working for Yamaha Motor Corp.

“He’s by far the best minibike racer I’ve ever seen in my life, based on who all he had to beat at the time,” said Dave Miller, who built his remarkable bikes.

“He was so good—almost unbeatable at one point on an 80cc bike, offered said Bruce Stjernstrom, head of Kawasaki Team Green back in the mid-eighties and now head of Kawasaki Racing. “The Yamaha really wasn’t the best at the time—the Kawasaki was pretty superior—but he still won. He was kind of the king of the minicycle kingdom.”

“I remember him as this very talented kid, and they said he was the next guy after I moved out of 80s,” says former Suzuki factory rider and current HRC Honda team manager Erik Kehoe. “I remember watching the results and almost knowing here’s the next guy that’s going to be coming, but then I don’t really know what happened.”

“When he was on the minibike he was a superstar,” said two-time AMA 125cc Supercross Champion Jeff Matiasevich, who raced against him before moving on to Team Kawasaki. “Maybe the dude got burnt out—he was racing his whole life at a top level.”

“He was just a fierce competitor. It’s a huge surprise, probably more than any other guy that grew up in the eighties, that he didn’t make it,” said 1994 125cc World Champion Bobby Moore. “That guy was just much superior over a lot of other kids.”

“I didn’t understand why he didn’t do well, but I heard stories,” longtime pro racer Kyle Lewis, one of his primary competitors back then, along with Moore, Matiasevich, Mike Healey, Mike Kiedrowski, Ron Tichenor, Willie Surratt—all of them future winners at the professional level. “I don’t know if any of its true, but mostly just how him and his dad had a big problem and falling out. Or maybe he just got tired of it—I heard that too.”

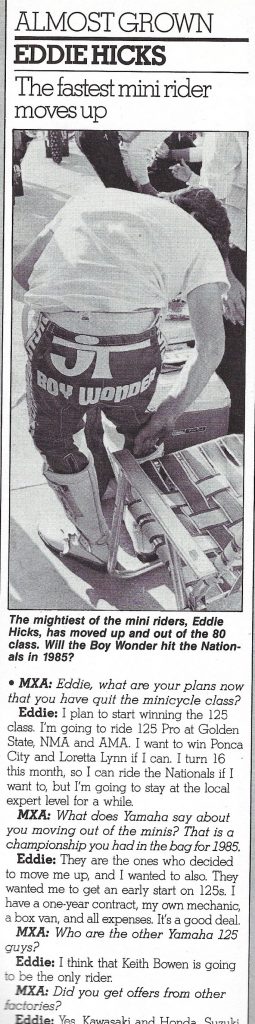

The kid they are talking about, the one who once had “Boy Wonder” stitched on the back of his pants, is now a man. Eddie Hicks is soon to be 49 years old and living in Hudson, Florida, which is about an hour outside of Tampa. He works at Walmart and lives with the mother of his son, Josh, although they’re not together anymore. Josh rides a KX80 for fun.

“He wants to race really bad right now but I can’t really afford it,” admits Eddie.

Hicks still follows pro racing. He’s an Eli Tomac fan and can’t quite bring himself to cheer for the Team Yamaha riders. (“I have mixed feelings about that,” he says.) He even got back on a bike a few years ago and raced the World Vets at Glen Helen, one of his old stomping grounds. But for now, Eddie Hicks has moved about as far away as he could from his old tracks in the high desert of California in order to try and get his life back on track.

“I’m trying to get back on my feet because I had some troubles in Cali. I’m not going to lie,” he says. “I was getting in trouble and stuff and that wasn’t working. The last five years… I don’t want to be negative or anything, but it’s not been the greatest.”

Jeff Ward. Brian Myerscough. George Holland. Erik Kehoe. Eddie Hicks. Damon Bradshaw. Brian Swink. Robbie Reynard. Kevin Windham. Ricky Carmichael. James Stewart. Mike Alessi. That’s a chronological list of a dozen can’t-miss kids who dominated minicycle racing and were literally superstars before they were old enough to drive a car. Eleven of those dozen names can be found in the AMA record books as AMA National or AMA Supercross winners, and some went on to rank among the greatest of all time.

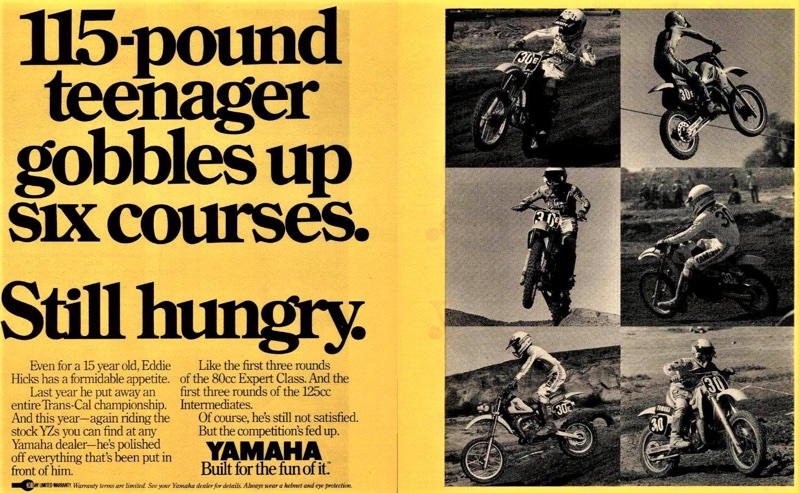

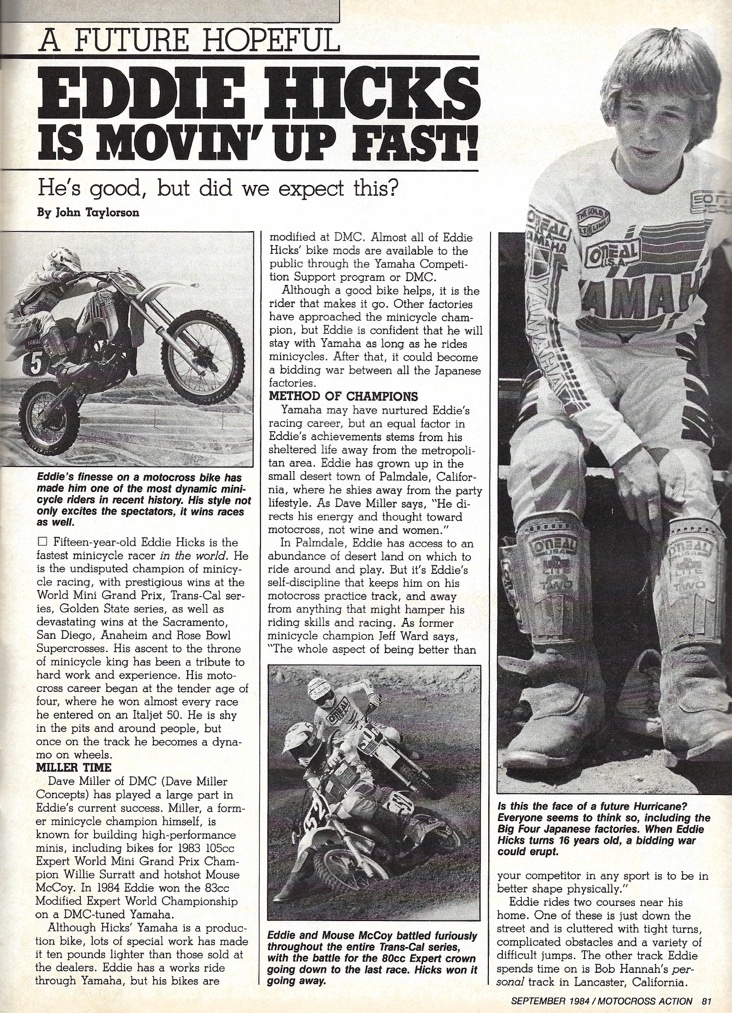

The one who didn’t make it is Eddie Hicks. A magazine cover boy on Yamaha’s next big thing behind Hannah, Broc Glover, Rick Johnson and Ron Lechien, Hicks started breaking through in the early eighties when he was eleven years old. He lived in Palmdale and had the vast California desert as a backyard to ride on. And Eddie rode a lot.

“I’d take off from my house and be up in the hills, making tracks of my own. Then I’d go to Bean Canyon, where Hannah made a track up there and I’d ride it all the time,” Hicks remembers. “He has an uncle up there. I would ride a whole tank of gas and come back. He’d go, ‘Go up there again. Do it again.’ And I would. Over and over.”

Many of those motos were done with his best friend Rick Hemme, who was a rising star for Suzuki and a bit older than Hicks. The two friends bonded and Hicks and Hemme rode “every day” since Eddie was about five years old.

“It wasn’t until probably around ’81 or ’82 that I was just starting to come on,” Hicks says of his first forays into bigtime minicycle racing. “I was probably about third or fourth to Hemme, Bruce Bunch, and Bobby Moore. I was right there. I didn’t beat those guys. I’d maybe beat Bobby once in a while because he didn’t always win. It was usually Rick or Bruce Bunch (Hemme’s R&D Suzuki teammate) and maybe Larry Brooks.”

Life changed for a lot of people, including Hicks, when Hemme, Bunch, and an even younger teammate named Kyle Flemming were all killed following the 1982 NMA Grand Nationals in Ponca City, Oklahoma, when the car they were riding in was hit by a train. Hicks wasn’t at the race, having suffered a broken leg while testing the new YZ80, but he was in Texas and got to see his friend Hemme before he passed away.

“We went and seen him in the hospital and it wasn’t good,” recalls Hicks. “I was only 13. He was 16. I don’t know if he was going to get the big ride [at Suzuki] or Bruce Bunch. But they were that good.”

Driven to depression over losing his best friend, Hicks poured his heart into doing more motos out in the desert, although now he was solo. And in the sometimes tragic way life works, losing his best friend helped Eddie Hicks out a lot.

“Rick Hemme is part of the reason why I feel that I got better,” Hicks says. “I was hurt from him passing away. I was real angry and I just put all the anger into the bike that year. And for some reason, everything clicked. Those guys couldn’t even come near me. Later on, at a Golden States race on an 80, they couldn’t even come near me. I was a half a lap ahead of them. I couldn’t believe it.

“I had lost my best friend,” he adds. “That’s what I feel, anyway. I’m not saying I wasn’t ready to go. I was ready, but that was part of the reason. It was a sad situation.”

Hicks was fast-tracked by Yamaha with more and more support. Chavez, then working for the Yamaha amateur program, was picked to help Hicks and his father George out.

“They kind of said, ‘Hey, we really think Eddie has a lot of potential, We want you to help him and keep his bikes going and all this kind of stuff,’” remembers Chavez. “So that’s basically what I started doing. Then I believe Bobby Moore left for Kawasaki and Eddie turned into our main guy. So, I built a lot of the bikes.”

Hicks continued winning in ’83 and ’84 matched up against rivals like Moore, Healey, Lewis, Surratt and more. But the Yamaha YZ80 wasn’t as good as the Kawasakis and Suzukis back then, so Hicks wouldn’t win the Stock class as much. However, he could easily win the Modified class—and even more so after he met a guy named Dave Miller.

“Eddie was one of Yamaha’s guys and I had some pretty cool Yamaha stuff,” Miller says, who you might know by his company name of DMC. “I think I let him try my bike that I was riding around one day at Saddleback at one of the races. He’s like, ‘I like how this runs.’ So, I just said, ‘Bring me your stuff and let’s work on it.’ That’s I think how it started.”

Hicks says, “Mouse McCoy was riding a DMC Kawi and it was fast. He let me ride it one day. I’m like, Holy cow, this bike is fast! Then one day, he just quit riding 80. He was just as fast as I was, but he was just done. That’s when Dave came to me and said, ‘Hey, I got a little Yamaha I can build you.’ He did, and that was all it took. Nobody could come near me. I’d just smoke them.”

“I think, to be fair, the production Yamaha compared to the Kawasaki, it really didn’t measure up, and I’m not just saying that because I work at Kawasaki,” says Stjernstrom. “That’s pretty much the way people saw it. Miller obviously did some good work to make that bike competitive. He had a really, really good rider at the same time.”

So Miller went off and built Hicks a one-off, aluminum everywhere, mega-horsepower bike for the Modified classes in 1984. Everyone contacted for this story remarked on that bike. It was absolutely next-level back then and currently sits at the Troy Lee Designs shop in Corona as a memento to another time.

“We took 22 pounds off a 136-pound mini bike,” Miller laughs of his masterpiece. “Disc brakes, all the stuff that hadn’t been done. Reservoir shock, aluminum gas tank and so on.”

“I know that when he got that bike and Dave put that big effort into the bike, nobody had ever seen anything like it,” Chavez recalls. “It was like a full-on works 80 bike.”

As good as the DMC YZ80 was, Hicks isn’t sure it helped future relations with the brand he grew up on.

“I like Dave Miller. He built my bikes. I’ve got nothing bad to say about him, but I’m not sure if Yamaha cared for it too much,” offers Hicks. “When he made that bike for me, it really didn’t say Yamaha on it, so they made me put Yamaha stickers on the side of the tank. I don’t think they appreciated that very much. I can’t say for sure. And if you didn’t have a fast bike, you were done, because those Kawasakis and the Suzukis built by R&D were so fast!”

During the winter of 1983-’84 the editors of Motocross Action put out a one-off magazine called MiniCycle Rider-Racer. It was a snapshot of what minicycle racing looked like in the early eighties.

“Those guys were superstars at 12 years old, 13, big time,” recalls Stjernstrom. “I think that played into it for some of those guys, too. They were big-time at 14, 15 years old. It was crazy.”

Needless to say, Eddie Hicks was all over that magazine. There were two photos of him on the cover alone, one aboard a YZ80, the other on a KX80. Inside he is featured in practically every story. There is a page asking the pros “Who’s the Hottest for ’84?” The dominant answer is Eddie Hicks. And with good reason—he had just won the CMC Trans-Cal Series, including its two races in San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium, topping Moore, Healey, Lewis, Mouse McCoy, Shaun Kalos and more. He is also the test rider for a shakedown of the new KX80, flicking the bike all over the pages. He is prominent in the coverage of both Loretta Lynn’s AMA Amateur Nationals and the Mini Olympics in Florida. To top it all off there is a feature-length interview where editor Dave Gerig talks to Hicks about life in the fast lane of minicycle racing, which at the time consisted of factory contracts, free bikes, $100 bonuses, being in ninth grade and relaxing after school by “riding bikes or go cruising for girls.”

At the end of the interview, when asked if he ever thought about quitting racing, Hicks answered honestly. “As a matter of fact, I thought about it a lot last year,” he admits. “When you’re racing all the time, the whole family just kind of goes nutso once in a while from the pressure of the racing season. Once we get it out of our systems, everything’s fine. But we always stick together. That’s the best part about racing—you can always count on them to back you up when the going gets really tough.”

If one looks close enough in MiniCycle Rider-Racer there are words of caution from none other than Jeff Ward, the OG minicycle king, who answered readers’ letters. When a kid asks the former minicycle prodigy-turned-Kawasaki factory superstar what the transition from minicycles to 125s was like for him, Ward answers, “When I first moved up to the 125 class, I got smoked! I saw Brian Myerscough move up (and do well), and when I moved up, I thought I would just keep on winning. Then reality hit me like a ton of bricks. I started out with all of the confidence in the world, only to find myself being lapped by a more experienced Brian. When you make the move to the 125s, you’re going to find out that you won’t be able to throw the bike around as radically as you could with an 80… Let’s face it, there’s a big difference in weight between the two, not to mention size.”

Hicks went to the 1984 NMA World Mini Grand Prix (the last at Saddleback Park) in April and raced his usual classes, as well as the Kawasaki Race of Champions. The KROC was an invitational race for 15 kids who had won a minicycle title in the last year. They would race three motos on 15 identical, stock Kawasaki KX80s which they would draw spoons for, turning the bikes in after each moto and then drawing again. (Although every OEM had contracted riders, they allowed them to participate in this race, a practice that ended in 1987 when Yamaha’s Damon Bradshaw refused to throw his leg over a green bike.) Although he had little experience aboard a Kawasaki, Hicks took to the bike immediately, winning two of three motos and the overall ahead of Bob Moore, who was a Kawasaki rider and knew the bike well.

Hicks also added an 85cc Mod Expert sweep, though he was given a run in the first moto by Team Green’s Kyle Lewis.

Lewis, for one, believes the big advantage wasn’t the bike, but Hicks himself: “He still had to twist the throttle. I don’t care if the bike is unbelievably better. He was jumping some crazy jumps—I remember that vividly. He just had a good package. The whole thing was good. He was confident. He was the man.”

Later than summer over 1700 riders entered the 1984 NMA/Yamaha Grand National Championship at Ponca City, Oklahoma. They would race together over seven days for practice, qualifying and the finals. Throughout the week Hicks would battle with a pair of future 125 Supercross and Grand Prix motocross winners, Mike Healey and Bob Moore. Healey, aboard the vaunted R&D Suzukis, was thought to be Hicks’ primary competition, and they would spend much of the week locked in battle. Moore, riding for Kawasaki Team Green, did manage to get a win from both of them, topping the 85cc Stock Pro handily.

“I kind of got a bad jump and those Kaws just out-pulled me into the first turn,” Hicks told Cycle News reporter Kit Palmer after trailing Moore and most of the rest of the pack in the early going of the final run-off. “I found myself in the pack and I got on the gas. I passed Healey for about ninth and then I went over a berm and dropped back. I’m definitely going to get them in the next race!”

Sure enough, in the next run-off was the 85cc Modified Expert, and this time Hicks put his DMC Yamaha to good use, chasing down Florida’s Ron Tichenor and Texan Jason Langford for the win.

In the 105cc moto Hicks’ bike seized in the first turn and Moore plowed into the back of him, knocking both out. Healey took full advantage and won the class.

“Eddie was just so fast. It was so hard to beat him. You had to have a killer start, and he had to have a really bad start most of the time,” Moore remembers. “In ’84, we went back to Ponca City. Remember the DMC 80, that bike that he had for the modified class? That bike was unbelievable. It was almost impossible. As soon as they rolled that thing out, it was like, oh, great, we’re going to be racing for second on this one.”

Still, Hicks was angry that his stock bikes were so underpowered compared to the Kawasakis and that he could not claim the NMA Grand National Championship because of his standard bike’s performance. When MXA pointed out that everybody had picked him to clean house and asked what happened, Hicks did not mince his words.

“Well, in order to win the National Championship, a rider has to do well in both the 83cc Stock and 85cc Modified classes. Whoever does the best in both classes becomes Grand National Champion. I didn’t have any problems winning the Modified class, but there isn’t too much you can do with a stock 1984 Yamaha. They’re just too slow to beat the Kawasaki. I was going really fast this week, but that’s the way it goes.”

Then he made it worse.

“If I had a different bike here at Ponca City, I would be the National Champion. That’s all there is to it. I wanted the Championship real bad!”

Finally, when asked if he would be Yamaha-mounted in 1985, Hicks replied, “We’ll just have to wait and see what happens. But if it takes a switch in brands to win the National Minicycle Championship, maybe by this time next year I’ll be mounted on a bike of another color…. Stock Yamahas are too slow.”

MXA also reported that as one of the most successful minicycle riders of all time, Hicks was making between $15,000 and $30,000 a season from Yamaha.

Hicks’ disdain for the Yamahas at the time was backed up by Bob Moore, now on a Kawasaki and considered the ’84 Grand National Champion. He said in the said magazine, “Riding the Yamahas here last year really hindered me, but not this year. Back in ’83, when I ride the ’84 Yamahas, I knew that they wouldn’t be able to win at Ponca City in the Stock class, and it takes a good Stock class finish to pull off the Championship. Just ask Eddie Hicks. I switched to Kawasaki so I could be National Champion.”

Ponca City was followed by the AMA Amateur National Motocross Championships at Loretta Lynn’s. Beginning in 1984 riders were limited to racing in two classes, three motos apiece. Hicks entered the 85cc (14-15) Stock and Modified classes. His rival Moore would not be there—he was 16 years old and too old for minicycle classes under AMA rules.

Eddie’s week was summed up simply by Cycle News: “Hicks six for six at Loretta Lynn’s.” The announcer at the ranch that year was a familiar voice in Larry Maiers, and he was already referring to the kid by the nickname on the back of his pants, “Wonder Boy.”

In the winter following the ’84 season many of Hicks competitors moved up to 125s. Moore and Healey signed Suzuki; Larry Brooks got a Honda Support ride. Todd Campbell and Bader Manneh went to Team Green. The exodus made it ever more obvious that there was nobody better on a small bike than Eddie Hicks, and the hype was at full-steam ahead. Yamaha was poised to groom him to be the next one after Glover and Johnson (Lechien had departed for Team Honda). Kawasaki Team Green also saw Hicks as the next great pro racer. One problem, though—they needed him to dominate in 80s one more year.

“We made a huge offer to Eddie to be a Team Green rider,” Stjernstrom remembers. “We needed someone to ride 80s for us in 1985. I think it pushed Yamaha into saying, ‘We really can’t compete with that.’ So they made him an offer to ride 125s instead. We had so many good guys on 125s, we didn’t need him on one at that moment.”

“We had big plans,” says Miller. “We had stood in that infield at Loretta’s, Mark Johnson [from Kawasaki], Bruce Sternstrom, and me, and watched Eddie ride away with it. Johnson goes, ‘Freaking $10,000 minibike you got.’ I said, ‘Excuse me? That’s a $20,000 minibike.’ So I said, ‘Look around, Mark. There’s nine Yamahas in the place and I brought three of them, and there’s 800 Kawasakis. I’d much rather be doing green stuff because I want to make some money doing this.’ So we struck a deal right on the spot that I would now be a Kawasaki guy.

“Part of the deal was, I would coax Hicks, who was still just 15, into riding one more year on green bikes through all the amateur stuff and dominate on that. And then after that, we would get him as a B-team guy like [Eddie] Warren and [Donny] Schmit and bring him up. Works parts with my engines and me working on the stuff. Then he would go A-team. It would be like a four-year tier deal. He would be guaranteed a Jeff Ward-type of ride in his third or fourth year.”

Hicks can’t recall the Team Green offer, but says that Suzuki offered him a three-year deal for $40,000 a year and also wanted him to ride 80s for one more year. He wasn’t having it, though. Having ridden a 125 here and there and enjoying it, Hicks forced Yamaha’s hand. If that if they wanted to keep him, it had to be on a 125.

If there’s a point in Hicks life where you could look at something and see where it went sideway, it was now.

“I think it was just a case of they moved him up too soon,” Chavez said. “I think it was the parents. They were a working-class family. They worked the night shifts at Lockheed. I think that they saw the potential and the money and all that kind of stuff and that was their big dream. Everybody pushed for him to be a pro.”

“Eddie’s parents, they never got in my way,” says Miller. “They hurt him later on the 125 thing. That was when the parents came in–at least George—and Yamaha jumped up and down and went, ‘No, man, don’t sign with Kawi, we’ll put you in the 125 Nationals on a works bike.’ George told me they’re going to do this. I go, ‘How much are they paying you?’ He said, ‘Well, nothing, but we keep all the prize money. And they fly us.’ I go, ‘No, no, no George, how long is this contract?’ It was for six months.”

Eddie Hicks puts the decision on himself: “My mom and dad tried to stop me. I didn’t listen to them. I wanted to make that money. I wanted to be a pro. I wanted to be with those guys. But the thing is, I should have took it a little slower. I should’ve took those deals or rode with Yamaha again on the 80s. I would have made tons of money on the 80.”

Leaving longtime sponsor O’Neal for another clothing brand was another change that Hicks regrettably went through.

“Jim O’Neal, I kind of got into it with him,” he explains. “JT Racing had offered me a big ride. I should have just stayed with O’Neal, because that was the start of my downfall… Trying to make decisions as a young man… If I would have had somebody to help me make that decision, someone to say, ‘Look, man, you can’t do that. We need to do this, we need to do that.’ I didn’t know.”

Hicks rode 80s a few more times in the fall of ‘84 along with some 125 Intermediate races (he usually won), now with more support from Yamaha. When the calendar turned to 1985, Hicks jumped into the pros, and Boy Wonder’s clock started ticking. Hicks rode the winter CMC Golden State Series as a 125 Pro, and at that time practically every top pro was racing that series. Hicks finished third in the series points behind Team Suzuki’s A.J. Whiting, Honda-supported Surratt, and right ahead of some guy named Doug Dubach.

More changes awaited Hicks as Chavez was pulled off duty as Eddie’s mechanic and Bob Oliver was assigned to take over. Chavez was bummed.

“I was pretty disappointed because Eddie and I had kind of built a relationship,” he says. “All the years that I worked with 80s and then going into 125. So, finally he got this shot and they ended up, I think it was Larry Griffiths, was Yamaha’s manager at that time, so they ended up putting him with Bob.”

Hicks looks back fondly at the time he and Chavez spent together and wishes it would’ve worked out differently.

“I’ve had some bad luck in my life just here and there, not knowing what to do mechanic-wise to saving the money,” he says. “A little bit of that is on Yamaha. They took Chavez away from me. We had a good thing going. He knew my bike. He knew me. They took him away from me and I wasn’t happy.”

1985 was the year that AMA introduced the 125cc class in Supercross, with regions for East and West. It was a high-profile stepping stone that immediately opened doors for young riders to claim wins and factory rides that were otherwise reserved for those who could immediately compete in the premier 250 class—guys like Rick Johnson and Ron Lechien. Among the early winners were several of Hicks’ slightly older rivals: Healey, Brooks, Bader Manneh and Todd Campbell. As a matter of fact, the weekend of Hicks’ last-ever amateur race—the 1985 NMA World Mini Grand Prix, now in Las Vegas rather than Saddleback, which had closed it’s doors forever—Bobby Moore won the Dallas Supercross as a factory Suzuki rider. Hicks, who turned 16 on March 31 of that year, went to Vegas and pretty dominated all but one moto in his 125cc classes, a terrible start ruining a perfect weekend to cap his amateur career.

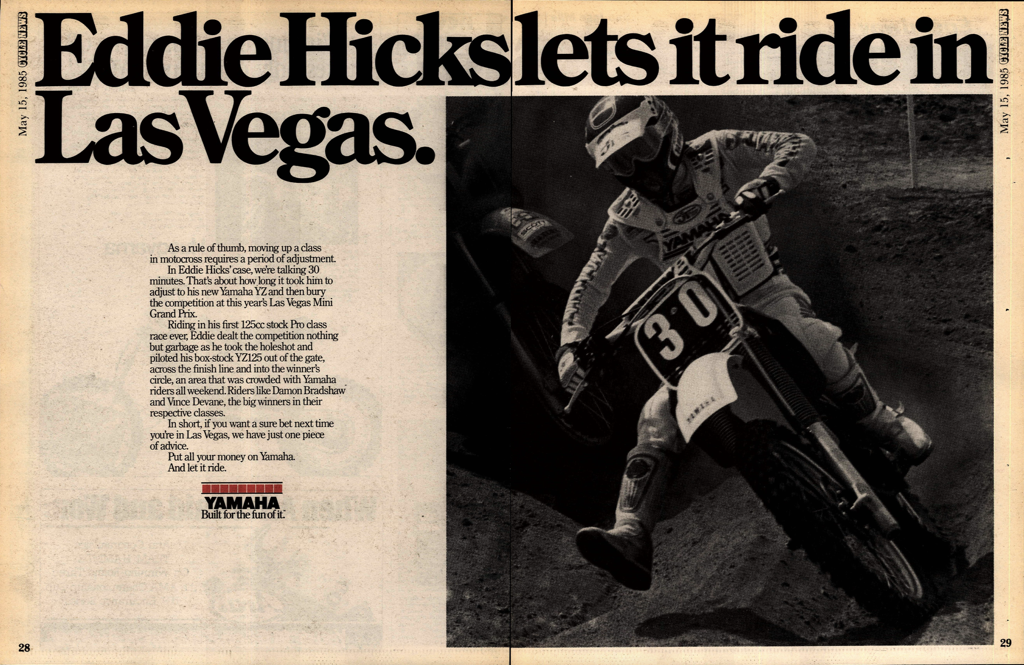

Everyone seemed to read the crystal ball the same way: Eddie Hicks had a very bright future. Yamaha rolled out a win ad in Cycle News celebrating his swift graduation to big bikes and his exploits at the World Mini GP. The ad landed in the May 15, 1985, issue of the newspaper, four days before Hicks would race in his first AMA 125 National. With glaring hubris it boasted how quickly the teenager had stepped up on his new motorcycle.

“As a rule of thumb, moving up a class in motocross requires a period of adjustment,” read the adspeak. “In Eddie Hicks’ care, we’re talking about 30 minutes. That’s about how long it took him to adjust to his new Yamaha YZ and then bury the competition at this year’s Las Vegas Mini Grand Prix.

“Riding in his first 125cc Stock Pro class race ever, Eddie dealt the competition nothing but garbage as he took the holeshot and piloted his box-stock YZ125 out of the gate, across the finish line and into the winner’s circle, an area that was crowded with Yamaha riders all weekend. Riders like Damon Bradshaw and Vince Devane, the big winners in their respective classes.

“In short, you want a sure bet next time you’re in Las Vegas, we have just one piece of advice. Put all your money on Yamaha. And let it ride.”

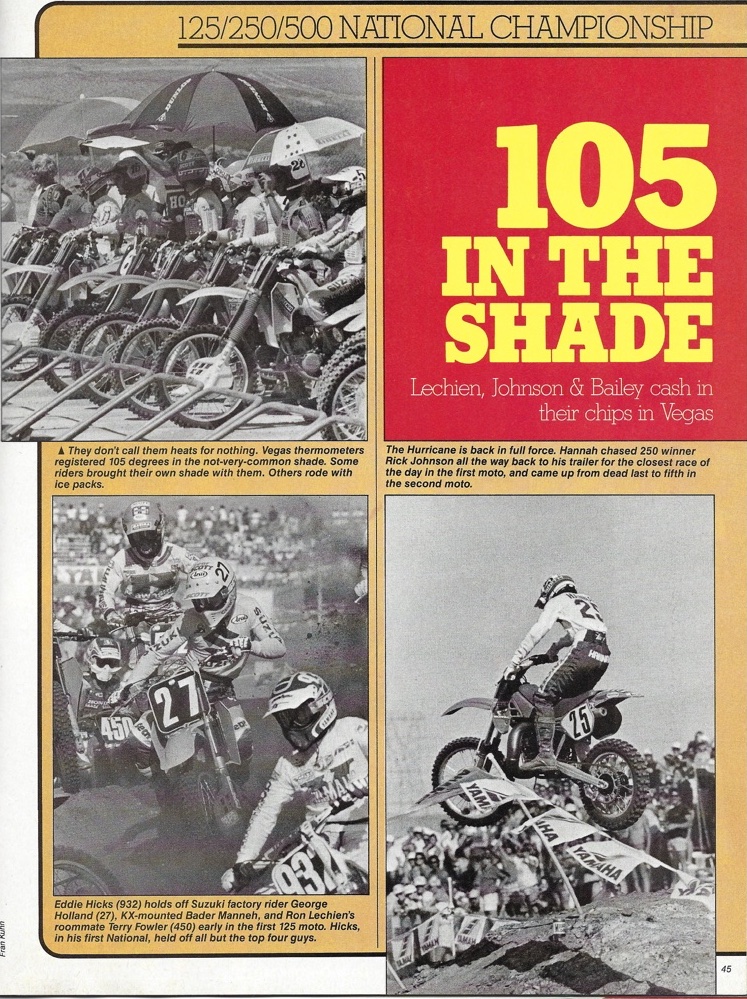

The very same track in Las Vegas that hosted the World Mini Grand Prix would also be the site of a single AMA Outdoor National, just two weeks later. It would mark the pro motocross debut of Eddie Hicks, running #932 on a factory-supported YZ125, but not a full-blown works bike; Yamaha was already prepping for the coming Production Rule, which would go into effect the following season. As a result, the bike seemed to lack some power compared to the works bikes around him. Still, Hicks was a solid 7-5 for fifth overall, beating many factory riders. It was a very good debut by any standards.

“Yamahas weren’t very good at the time. They were horrible,” admits Chavez. “The 125s were pretty slow. It took a lot of work to try to make them be competitive. And they still didn’t handle very well.” Adding to the problem, as far as Hicks goes, is the fact that Miller was now focused more on Kawasakis—that’s where the money was at the time. Still, Hicks’ talent and slight stature gave him a fighting chance.

“In Vegas I even pulled the holeshot on Lechien on that works Honda!” Hicks recalls with a big smile. “I had the lead for about a half a lap and then he got by me. Somebody else passed me, a couple other people, and then that was it.”

“He had a great style. He was always fairly short for everybody around,” Oliver remembers. “He had a really great stature on the bike for being such a short kid. But he was really stout, strong. I was just kind of setting it up for a guy that was… He was like the Jeff Ward type-cast thing.”

Hicks would only do a couple more 125 Nationals that year. In late July, when he probably should have been in Ponca City for more seasoning, Hicks was in Binghamton, New York, for the Broome-Tioga 125 National. Hicks went 38-16 after tangling with another rider: “Mike Jones came across on the takeoff in the first moto, took my front wheel off, and I endoed. I hurt my wrist real bad.”

But not bad enough to miss his first real supercross, which would come on August 17, 1985, at the Pasadena Rose Bowl. Racing in the 125cc West Region finale, Hicks ran up front and placed third behind Larry Brooks and Dean Matson, and a few spots ahead of Moore, his old rival, who placed seventh.

There is video from this race that briefly focuses on Hicks. It’s plain to see that he’s small on the bike, and his style resembles a young Ryan Villopoto, circa 2006-’06, when he was still small and learning the ropes on big bikes. For comparison’s sake RV’s first AMA 125 Supercross—the ’06 Anaheim opener—was the third race of his career, following the last two outdoor nationals of ’05. Twenty years earlier the ’85 Rose Bowl was Hicks’ third pro race, after two pro nationals. Villopoto finished second in his debut; Hicks finished third.

One week later at Washougal, Hicks lined up for the last race of 1985 and went 13-6 for ninth overall in the 125 National. Three top-ten finishes in six career motos, as well as a podium finish in his one and only SX race to that point was a good showing for the kid, which earned him national number 57. Things were looking up.

Yet not to everyone at Yamaha. Used to seeing 16-year-olds like Rick Johnson and Ron Lechien winning races, they still didn’t seem completely sold on Eddie Hicks. When it came time to field a team for 1986, they were stung by the departure of Johnson to Team Honda. That and the fact that the new AMA Production Rule didn’t exactly get them on the same level as the other three brands’ racing equipment seemed to make them tighter than expected with the purse strings. While Honda lined up with Johnson, David Bailey, Johnny O’Mara and Micky Dymond, Yamaha would have Broc Glover, Keith Bowen and Scott Burnworth. Hicks would only be given a support deal.

“In 1986, Yamaha, they gave me my bikes and they said, ‘You have to get your own way there,’” explains Hicks. “All the money that I had made off the mini class, I put into the season.”

The ’86 AMA Supercross season opener at Anaheim is remembered for the titanic battle between Honda teammates Rick Johnson and David Bailey, but in the 125 main that night, Kawasaki’s Tyson Vohland and Donny Schmit went 1-2 while Hicks was a close third. Unfortunately for Hicks, it was the highlight of his first full rookie season. Hicks didn’t break the top ten again until five months later at the LA Coliseum, when he scored fourth.

Hicks’ father George was usually a domineering presence at the races, while the boy stayed pretty quiet. More than a few people who I talked to for this story said that Eddie never said much. It was George who steered the boy’s career. But that began to change in 1986 when took a step away, just as Eddie’s results began to diminish.

“I didn’t really like the situation my dad put me in,” Hicks says of that critical ’86 season. “After I got a fourth or something, my dad says, ‘You’re going to go with these guys to New York, with Willie Surratt and all them, to travel the Nationals.’ So I traveled that summer with Willie Surratt, which was a nightmare.

“I know Willie real well. We’ve been through it all,” Hicks says of a fellow prodigy, though one notorious for sometimes being difficult to get along with. “We traveled the Nationals and, like I said, the bike was no good. I was trying to get people to work on it. Yamaha wasn’t really helping me. I had to get whoever I could get to work on it.”

“All the dads were bad back then, but out of all of them, my dad was the worst. He made a fool out of himself sometimes at the racetrack,” Hicks said. “Not that I want to talk about my dad. He’s a good guy. I love him to death. But he just wanted me to win. Anybody who was around him knew who he was because he said what was on his mind, whether you liked it or not.”

When I ask him how bad it got, Hicks pauses to measure his words, then admits, “When I was younger it got physical. When I [turned] 16, he couldn’t really control me no more.”

“I remember his mom being pretty quiet and very nice, but the dad, of course, was pretty hardcore,” recalls Bobby Moore. “But at that time, it was kind of just the norm, it really was. Eddie’s dad was hard on him, but then again, so was my dad. It was one of those things where they’re spending thousands of dollars to go to the races and they don’t want us goofing off. If we’re going to try to do this for a living, you’ve got to bust tail. I remember his dad just being a pretty nice, simple guy that wanted his kid to do well.”

By the summer of ’86, Eddie Hicks was in a slump. Ninth overall with a fifth in one moto at Southwick was the highlight. Looking at Cycle News archives, though, you see Eddie sweeping both 125 Pro classes in the fall of 1986 on the SoCal local circuit, beating guys like Dubach, Matiasevich and future three-time AMA Motocross Champion Mike Kiedrowski. Evidently, the speed was still there, just not in the races that really mattered.

Hicks’ program wasn’t good, his bike wasn’t good, and off the track things were heading south. The top-tens were slipping away. The big factory rides and bonuses were getting further and further away. Now guys Vohland, Surratt, Schmit and Tichenor were the ones winning 125 Supercross main events, Moore was on the European Grand Prix circuit, Healey and Brooks moved up to 250cc rides, and guys like Matiasevich, Kiedrowski and Lewis were moving up. So after four years together, Yamaha and Eddie Hicks parted ways—he was not going to be their next Johnson or Lechien, let alone Bob Hannah.

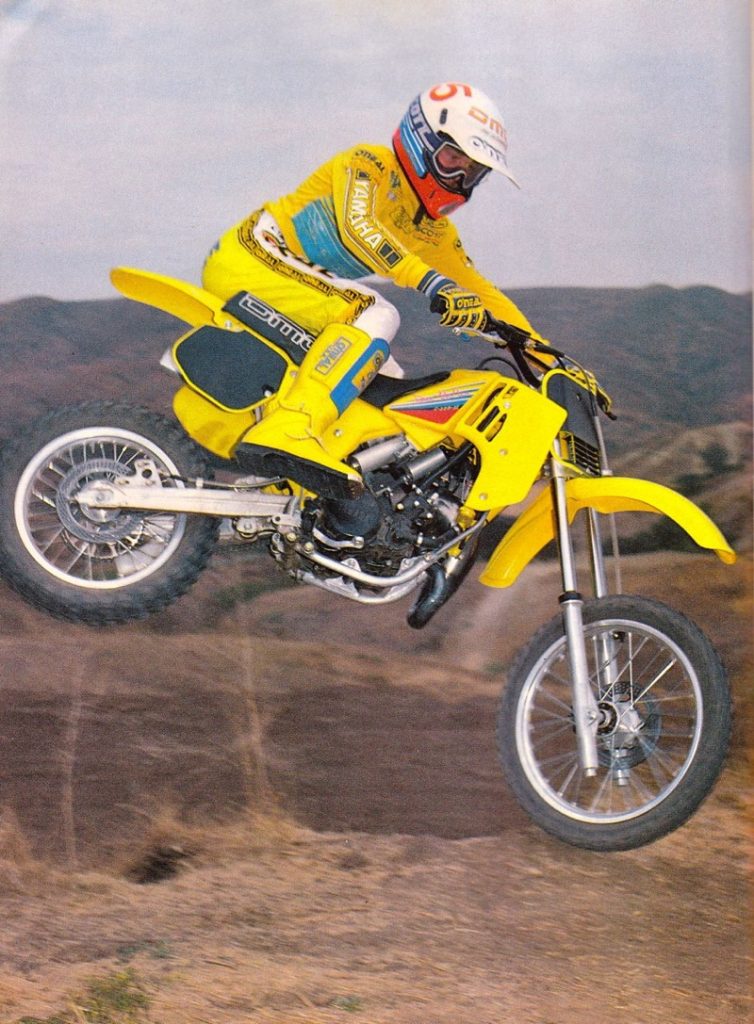

Fortunately, Kawasaki’s Mark Johnson remembered Hicks from that day of standing in the infield at Loretta Lynn’s and decided to give him three bikes and some parts for the new AMA National #42. It wasn’t much but for Hicks, but it represented a fresh start, as he also went from JT to THOR/Hallman gear.

“When I got the Kawi deal, I was happy,” Hicks says. “My contract was, the better I do, the more my contract goes up. So the first race (Anaheim) I didn’t do very good. I got eighth on a stock bike. Since it was a Kawasaki, I went back to Dave Miller and I said, ‘I don’t have no help. My dad ain’t helping me. I just need a little help with my bike.’ He whipped it up. That thing was railing. It was so fast. I loved it. It was the best bike I ever had.”

Hicks would score a third the next week in Houston behind Keith Turpin and his old travelling partner Surratt. Then came the San Diego, and with it Hicks’ best chance to win a professional race. He started out with the holeshot, though he was soon passed by Honda Support rider Kyle Lewis, yet another minicycle rival who had just turned 16. Hicks stayed close to Lewis throughout the 15-lap main event but he could not make a pass. Lewis held on by inches and became the youngest 125 SX winner ever at just over 16 years, three months, a standard that would stay until James Stewart showed up fifteen years later.

Ironically—tragically—Kyle also had a somewhat overbearing father, Matthew Lewis. In the middle of the San Diego race Mr. Lewis suffered a heart attack. Before Kyle had even taken the checkered flag his dad in an ambulance. He died outside Jack Murphy Stadium before he could be airlifted to a nearby hospital.

So was Eddie Hicks back? An 8-3-2 to start the year in the 125 SX West Region sure seemed to indicate that he had gotten things back on track. But then as quickly as he was back, things went wrong fast for him at the Kingdome in Seattle, where he crashed and hurt his wrist. Again. He limped home in 18th. If there was a breaking point in Eddie Hicks career, it was thatr night in the Pacific Northwest.

“You know how in the Kingdome you used to pit inside, out on the floor, in front of the fans? The fans are all right there, and after that race they’re watching me and my dad arguing and screaming at each other,” he recalls. “We got back to the motel and by that time I was pretty much done. I was just frustrated with my family life. It wasn’t going well. And the travel part wasn’t happening. My dad didn’t want nothing to do with it no more after that, and he was kind of the only way I could get there. The racing, I still loved, but I didn’t love nothing around it.”

Hicks raced the rest of the ’87 125 SX West Region on his own, with a broken spirit and banged-up wrist, ending the season eighth overall. That season’s 125 Regional Champions were Ron Tichenor in the East and Willie Surratt in the West.

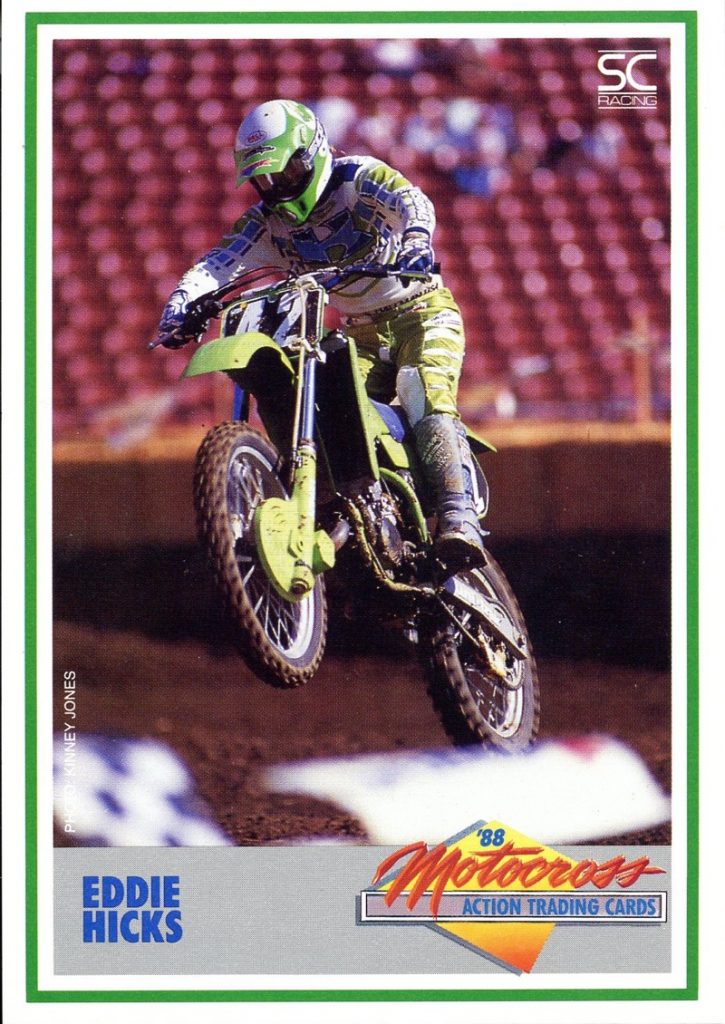

(TRADING CARD)

In the winter of 1987-’88 Hicks was featured on one of those rare, oversized SC Racing Motocross Trading Cards, riding the #42 Kawasaki. The back of the card listed his vitals: He was born on March 31, 1969, in Palmdale, California. He was 5’ 5” and weighed 135 pounds. It also listed his “career highlights” like this:

’84 1st Place — 85cc Modified Class – Amateur Nationals

’84 1st Place — 85cc Stock Class – Amateur Nationals

’84 1st Place – World Mini Grand Prix – Race of Champions

’86 2nd Place – 125cc Pro New Jersey State Championship

AMA Pro Statistics

’87 8th Place – 125cc West Supercross Championship

It was already becoming plain to see that Hicks’ minicycle career was defining him while his pro career was relatively a disappointment.

Hicks picked up some Yamahas for ’88, raced some of those Mickey Thompson Ultracross races alongside trucks and ATVs, did the local stuff, but not to great results. Then Eddie Hicks quit. Just four years after he was the can’t-miss kid won swept all six motos at Loretta Lynn’s, appearing on magazine covers and started a bidding war between two OEMs, he was done with the sport.

Or so he thought. Eddie came back a little over a year later, this time without his father George, doing it for himself and the love of dirt bike racing, plus the fact that he could still go very fast and earn a few bucks here and there.

Meanwhile, on the national scene, Kiedrowski was battling Yamaha’s next prodigy Damon Bradshaw for the 125 AMA National Motocross Championship, Matiasevich was dominating in the West, Moore and Healey were factory KTM riders in Europe racing the 125 Grand Prix circuit, and guys like Brooks, Tichenor, Dubach and Lewis were already in 250 Supercross. The sport went on without him.

Riding Hondas one year, Suzukis another, and even getting a KTM 500 at some points, Hicks was still a constant name at all the big Southern California races. It became a bit like “Where’s Waldo?” in each week’s Cycle News. For example, in 1990 at a GFI race at Perris, Hicks won the 500 Pro class. The 125 winner? Some Kawasaki Team Green hotshot named Jeremy McGrath.

Fast forward to 1992. Erik Kehoe, then with Honda of Troy, remembers a chance encounter: “I was out riding with Mike Kiedrowski in the hills. We had stopped after a moto to take a break. We were sitting on the tailgate of our truck and these three guys came riding through with desert bikes, just T-shirts on. They came cruising up to the truck and I was like, Who are these guys? One of them pulls off his goggles and it was Eddie Hicks! He was out in the middle of the hills, just riding in a T-shirt. We chatted with him for a few minutes and then he’s like, ‘Alright, guys. See you later!’ That’s the last time I’ve seen him.”

More random results: In a ‘92 125cc Pro race at Glen Helen, ’91 Loretta Lynn’s Senior Mini Champion and future FMX god Mike Metzger finishes second Eddie Hicks. And then Hicks scores one point for 20th spot at the 1991 Hangtown National that was infamous for its muddy conditions, called off after a single moto. If there was a metaphor to Hicks’ career, it was that miserable day at Hangtown, because that was the last point he ever scored as a professional racer before it all washed away.

“I was kind of embarrassed, to be honest with you,” he says of the end of his pro career. “But I got the racing in my blood. It’s just the way it went.”

It was around this time the real world caught up to Hicks as he wandered through life, trying to figure out what was next.

“Life wasn’t so good for me for a while,” he admits. “I’ve done my share of partying. There was a guy that I rode for that probably talked about me, and there’s probably been a few people talking about me,” he said. “I’m not saying that I’m innocent. I wasn’t racing no more. I wasn’t factory no more. I never did anything party-wise whenever I raced.”

His old engine-builder Miller still races Hicks’ struggles back to that crossroads in 1984 where he had to choose between one more year on 80s with Kawasaki or a 125 support deal with Yamaha.

“Eddie, if he would have followed the Kawasaki program because, still to this day, they know how to build them,” says Miller. “They were bring them up from 60 to 80, 105, 125. He gets rushed, and then he not only gets rushed, he gets rushed on maybe the worst production 125 they have at the time, the ‘85 Yamaha.”

“For somebody of that talent, I don’t know why things didn’t work out, exactly,” Stjernstrom remarks. “It wasn’t lack of talent, nor do I think it was a lack of skill. It was just I think sometimes the transition from mini-bikes to big bikes—I think that’s the thing was the big element of this.”

“I think the dude got burnt out,” offers Matiasevich, who went on to have a long career as a Kawasaki and Suzuki factory rider. “He was racing his whole life at a top level. Had a ton of pressure. Also, he was so short, he could barely touch the ground on the bigger bikes. He was always a nice guy, never had an issue, and we raced clean together.”

Chavez, who would eventually get the next Eddie Hicks while at Yamaha by working for Bradshaw, just thinks Eddie’s shy nature and rush to the pros was an issue.

“It took a long time for Eddie to really figure out that he was actually a pretty good rider,” says Chavez. “Guys got to have a little bit of confidence. They got to feel it. So it took Eddie a while when he made that top step into the 80 class to realize that he was actually the guy, and he never felt it on the 125.”

“When I was on the Kawi in ‘87, there was no doubt in my mind. I was even fast on that 250….” Hicks trails off, pondering what could have been. Does he ever think about what could have been? “Yeah, it sometimes beats me up,” he admits. “I try not to do it too much. I didn’t do it when I was younger, but I do it now that I’m older. Probably about ten years ago I didn’t really think about it so much, but now I do.”

All these years later, Eddie Hicks and his father George talk and get along, but there’s not a ton of communication between the two. You get the sense in talking to Eddie that there’s some regret for things his father did, both to him and for him. But at the same time, Hicks seems to realize that life is what it is now—and it’s not what he thought it would be as that Wonder Boy racing minicycles.

Today Hicks keeps a very low profile online. He rarely posts anything on his Facebook page. As a matter of fact, as we were completing this story there were just two photos that he has posted of himself, and that was back in 2016. One with his ’84 Loretta Lynn’s trophy, the other from a magazine shoot on the DMC bike—the one that now sits on display in the showroom of Troy Lee Designs in Corona. Still, it’s enough to see how influential he was to a generation of minicycle fans by some of their responses.

Chris Miles That pic was on my bedroom wall for a couple years. One of the Dopest minicycle photos of the 80’s! Even 90’s for that matter.

Stewart Kingston Eddie Hicks even in Australia that pic was hanging on a few walls mate

David Hopwood That’s the money shot ! Look at that ! Rear disc brake ! A full on works bike ! Everybody was jealous

Terry Bostard Eddie Hicks man you were the man – not to mention those DMC scooters

“When I see Facebook and all the pictures coming out and people are like, ‘Look at this!’ And they’re sending me pictures I’ve never seen before, I’m like, Wow, I forgot about all that,” says Hicks. “It’s kind of rough. I’ve had a rough life, so a lot of my pictures and stuff are all gone…

“The last five years, I don’t want to be negative or anything, but it’s not been the greatest.”

And that’s it: Fourteen career 125 Supercross races for Eddie Hicks with seven top-tens; twelve career 125 Nationals with three top-tens. No wins in either. It’s nowhere near what Eddie Hicks nor anyone else thought he would do back in those formative days. Standing on the podium indoors or out at the highest levels of professional motocross is a pretty big accomplishment, but no one who was at Loretta Lynn’s in 1984 or Las Vegas in 1985 would’ve predicted this is how it would have turned out. Ask anyone now who was around back then and they’ll all probably tell you that Eddie Hicks was the best there never was.

POSTSCRIPT:

Round eight of the 2018 Monster Energy AMA Supercross Championship took place in Tampa, Florida, maybe 45 miles from where Eddie Hicks now lives. So for the first time in years, Hicks decided to go to a supercross race. He brought his son Joshua to see the sport Hicks was once practically ordained to rule. With the help of Feld Motor Sports and Cycle Trader Yamaha we got them track access. Eddie was excited, saying he hadn’t been on a supercross track since he last raced one nearly thirty years ago, and at one point said that seeing the finish line was “getting me going and making me think about racing again.” His son Josh said that he had been reading more about his dad’s racing career and said he had been finding out that Eddie was, in his words, “really good,” and he expressed a desire to race once he got his KX80 up and running.

The rest of the day was spent walking around the pits and checking things out. Hicks was grateful to everyone for getting him the passes and mentioned that he’d reconnected with some older racing friends. He seemed very happy to be back at the races.

A couple weeks later we tried to follow up with Eddie to get some more of his thoughts about the Tampa SX, what he thought of the racing and just finish this whole conversation up, but there was no response to numerous texts. Finally, we called and got that bland, automated reply: “The person you dialed is not available to receive calls at this time”.

And just like that, Wonder Boy dropped off the map completely, leaving us once again with more questions than answers when it comes to the legend of Eddie Hicks.