For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the last of the pre-KIPS Kwackers, the 1984 Kawasaki KX250-C2.

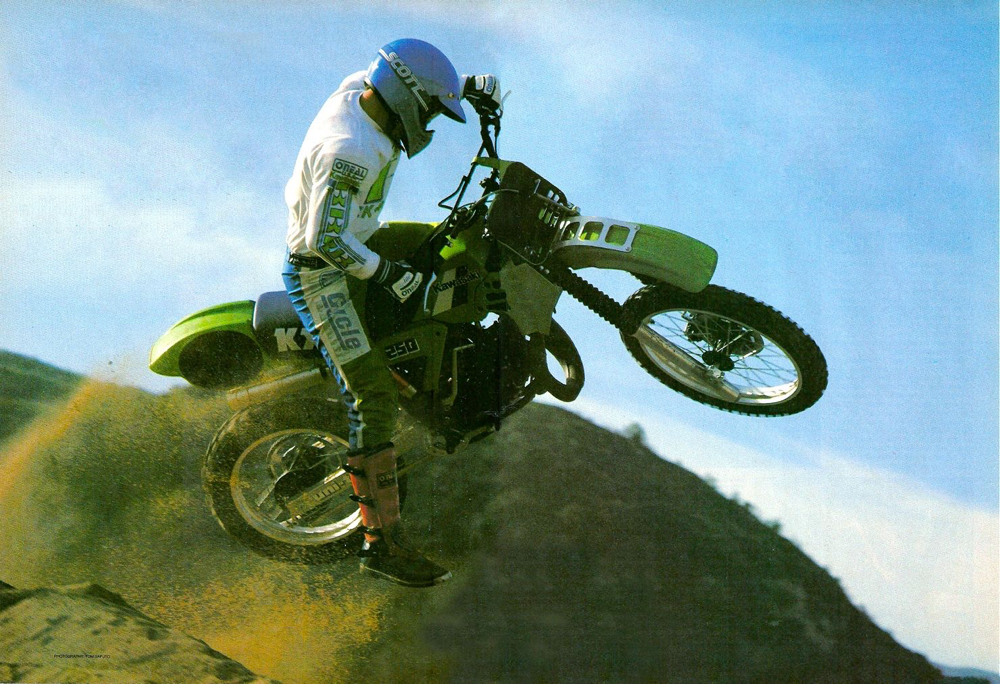

In 1984, the Kawasaki KX250 was not at the top of most rider’s shopping lists. Tall, long and slightly spacy looking, the KX250 was the green-headed stepchild of the 250 class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1984, the Kawasaki KX250 was not at the top of most rider’s shopping lists. Tall, long and slightly spacy looking, the KX250 was the green-headed stepchild of the 250 class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The seventies and early eighties were a tough time to be a Kawasaki off-road enthusiast. Even though the Japanese industrial giant had been one of the first Nipponese manufacturers to dip its toes into the motocross waters, the red (and later) green machines had never really enjoyed the success of their rivals. In the early days, Kawasaki motocross machines were produced in very limited numbers and many dealers did not even bother to stock them. They were fairly prominent in professional racing, but a bit player at the grass-roots level. Sparse parts availability, meager aftermarket support and a general lack of competitive products made the green machines an afterthought in the minds of most motocross hot shoes.

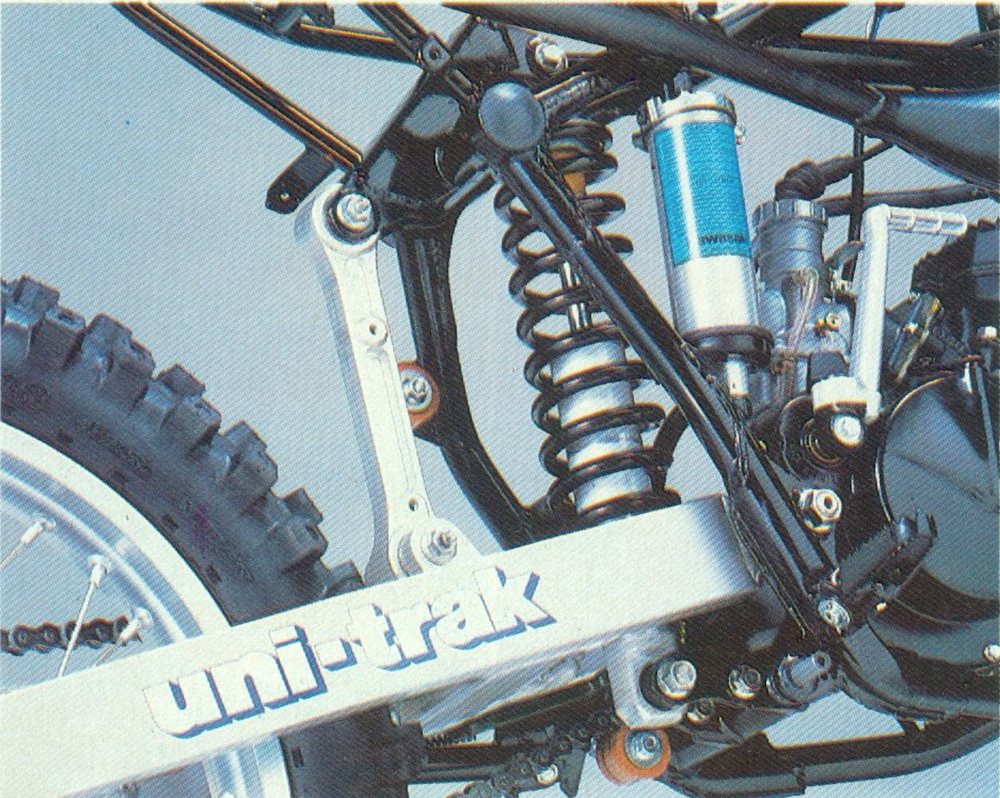

In spite of often being at the forefront of technology with innovations like their Uni-Trak rear suspension, Kawasaki lagged behind the other Big Four manufacturers in sales and dealer support. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In spite of often being at the forefront of technology with innovations like their Uni-Trak rear suspension, Kawasaki lagged behind the other Big Four manufacturers in sales and dealer support. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Even though Kawasaki was lacking in sales compared to its rivals, they continued to be at the forefront of motocross innovation. In 1980, they became the first manufacturer to introduce a linkage-equipped single shock rear suspension system with their Uni-Trak. Then, two years later, they became the first Japanese brand to equip their machines with a hydraulic front disc brake. In spite of this innovative spirit, however, the green machines continued to be a tick off the best brands from Europe and Japan.

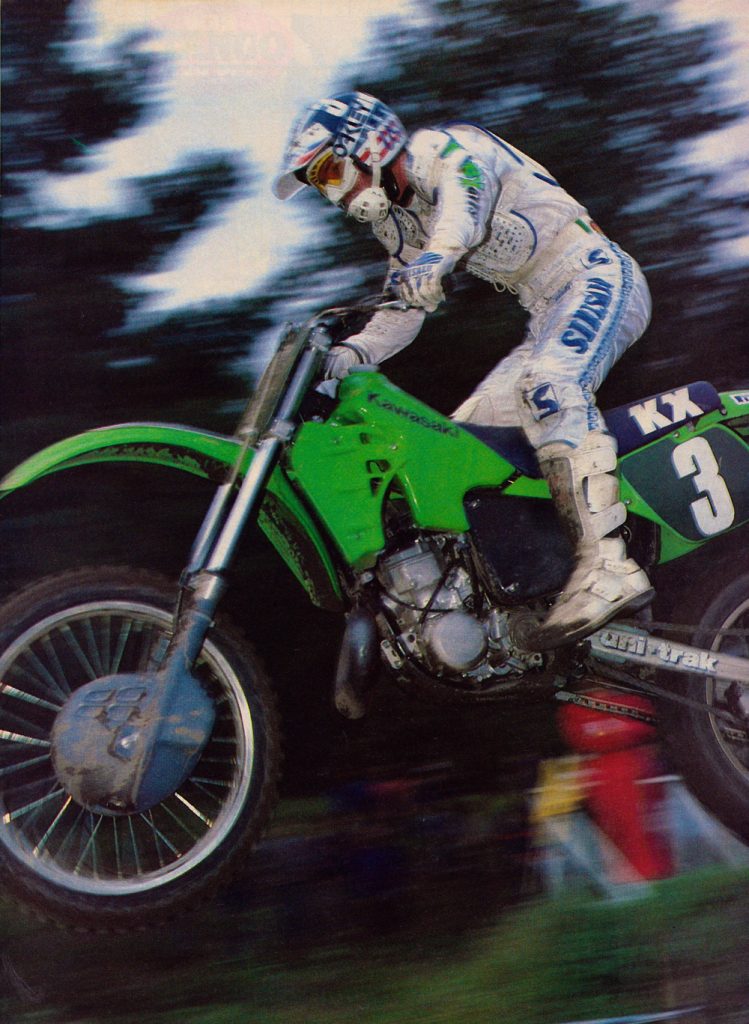

In 1984, Jeff Ward was Kawasaki’s 250 ace. Thankfully for him, his SR250 shared absolutely nothing with the stock KX250 besides the color. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1984, Jeff Ward was Kawasaki’s 250 ace. Thankfully for him, his SR250 shared absolutely nothing with the stock KX250 besides the color. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Then, in 1983, Kawasaki’s fortunes finally began to turn. They continued to show utter futility in the Open class, with the abysmal KX420/KX500, but the smaller bikes were actually starting to gain traction. The new KX60 and KX80 led the charge, with class-leading performance that left their red and yellow rivals in the dust. In the 125 and 250 classes, the KXs were not quite as successful, but at least they were competitive.

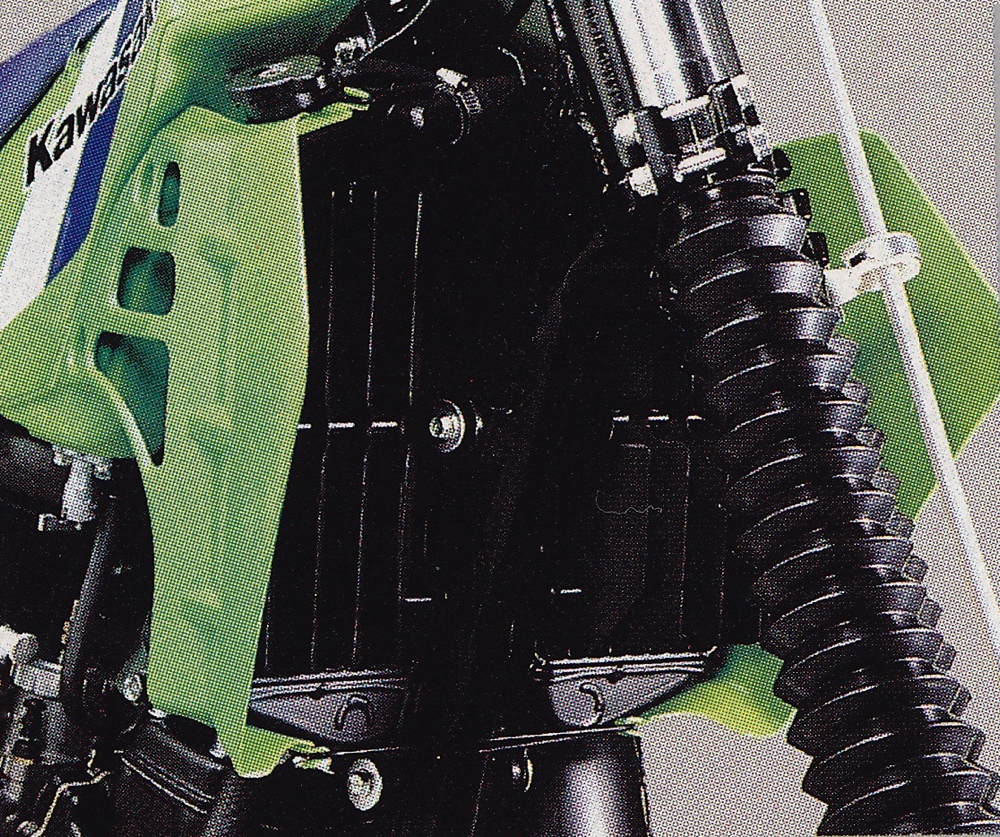

One of the few major changes on the KX250 for ‘84 were these new radiators that were repositioned to sit two inches lower on the chassis. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

One of the few major changes on the KX250 for ‘84 were these new radiators that were repositioned to sit two inches lower on the chassis. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1983, the KX250-C1 had offered a solid low-to-mid powerband and spacy looks. The bike was tall and slightly ungainly, but the new liquid-cooled motor provided solid thrust and the Uni-Trak suspension did a good job of absorbing mega-leaps. As the only bike in the class with a disc brake, it also offered far more stopping power than the drum-equipped competition. Overall, it was a solid effort, but not nearly as complete a package as Honda’s excellent CR250R.

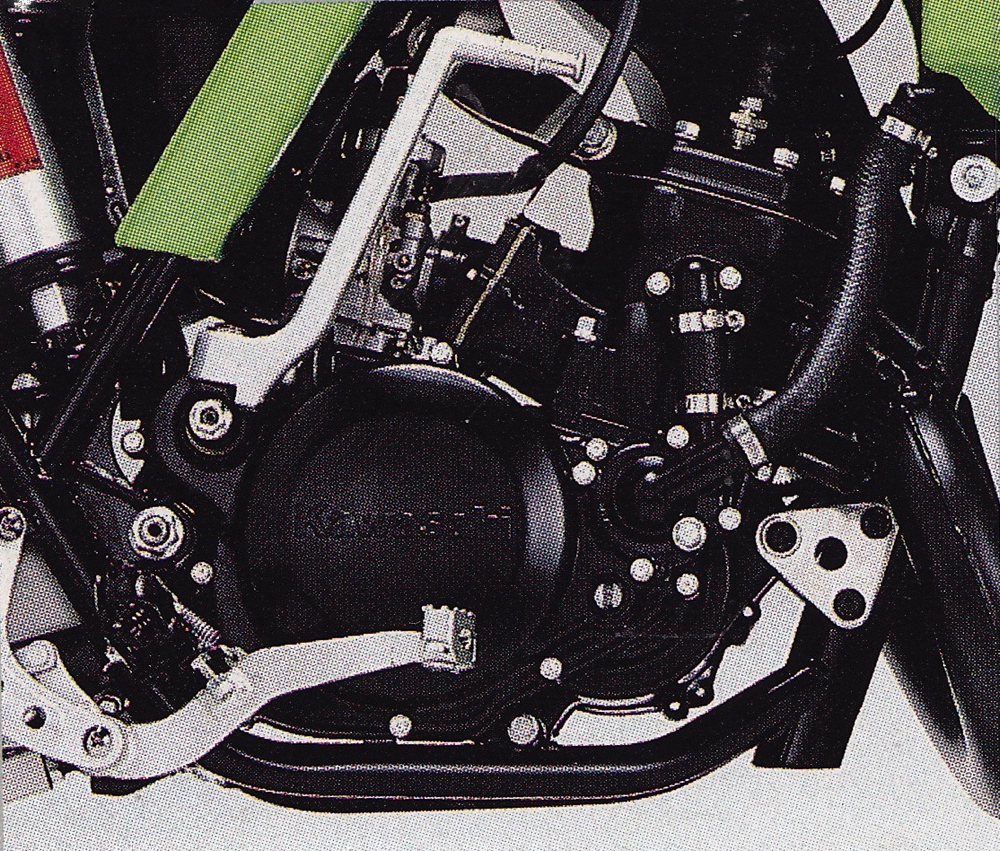

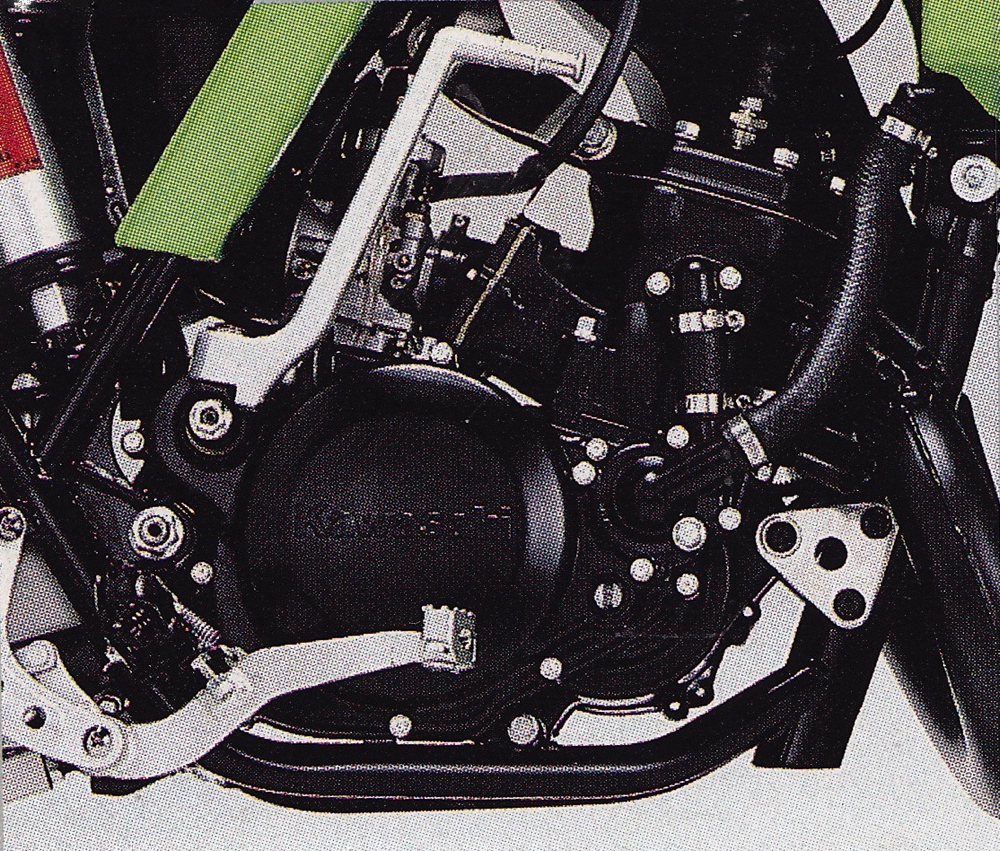

The 249cc two-stroke mill on the ’84 KX250 was a straightforward cylinder-reed design that lacked any type of exhaust valve mechanism. In spite of its relative simplicity, it offered a potent and competitive powerband. Low-end and midrange power were very good, with a solid blast that rocketed the KX out of tight turns. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The 249cc two-stroke mill on the ’84 KX250 was a straightforward cylinder-reed design that lacked any type of exhaust valve mechanism. In spite of its relative simplicity, it offered a potent and competitive powerband. Low-end and midrange power were very good, with a solid blast that rocketed the KX out of tight turns. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1984, Kawasaki decided to spend the majority of their R&D budget on the 125 class. The KX125 was all-new from the ground up and by far the best green tiddler ever offered for sale. The new bike looked and ran like Jeff Ward’s 1983 SR125 factory bike and romped on the eighth-liter competition.

The Jolly Green Giant: Very tall and large overall, the ’84 KX250 felt much more like an Open bike than a nimble 250 on the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The Jolly Green Giant: Very tall and large overall, the ’84 KX250 felt much more like an Open bike than a nimble 250 on the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With the 125 receiving the lion’s share of Kawasaki’s budget for ‘84, the KX250 had to make due with some fairly minor changes. The new ’84 KX250-C2 maintained the same frame geometry as 1983, and carried over much of the bodywork. The sole exceptions were the new tank, shrouds and seat required to accommodate the new lower-mounted radiators. The looks remained uniquely “Kawasaki” and most people either loved it or hated it. Compared to the sleek new KX125, the KX250 looked like a reject from another era. The oddball rear fender/number plate combo remained and gave the bike a tall and strangely proportioned appearance. The cool (or gaudy, depending on your perspective) gold rims and accents of 1983 were also retired, in favor of a more understated (or boring) silver for ’84. The new saddle featured an up-the-tank “safety-seat” design for the first time and traded the black of 1983 for a dark blue in 1984.

While the power output of the KX was competitive, the rest of its powertrain left a bit to be desired. The transmission was notchy and the clutch was an utter disaster. It chirped, chattered and lurched under even light use and gave up the ghost entirely if pushed. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While the power output of the KX was competitive, the rest of its powertrain left a bit to be desired. The transmission was notchy and the clutch was an utter disaster. It chirped, chattered and lurched under even light use and gave up the ghost entirely if pushed. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the motor department, the new C2 kept the same basic power package as the C1, with a few important modifications. The 249cc mill maintained its 70.0 x 64.9mm bore and stroke, but offered slightly more compression (9.1:1 vs. 8.8:1) and a hotter ignition for ‘84. On the intake side, a new 38mm Mikuni replaced the infuriating-to-jet 38mm Keihin of ’83 (goodbye screw-slot jets!) and a new pipe helped extract the spent gasses. The liquid cooling remained, but new radiators lowered the center of gravity by relocating them 2 inches lower for 1984.

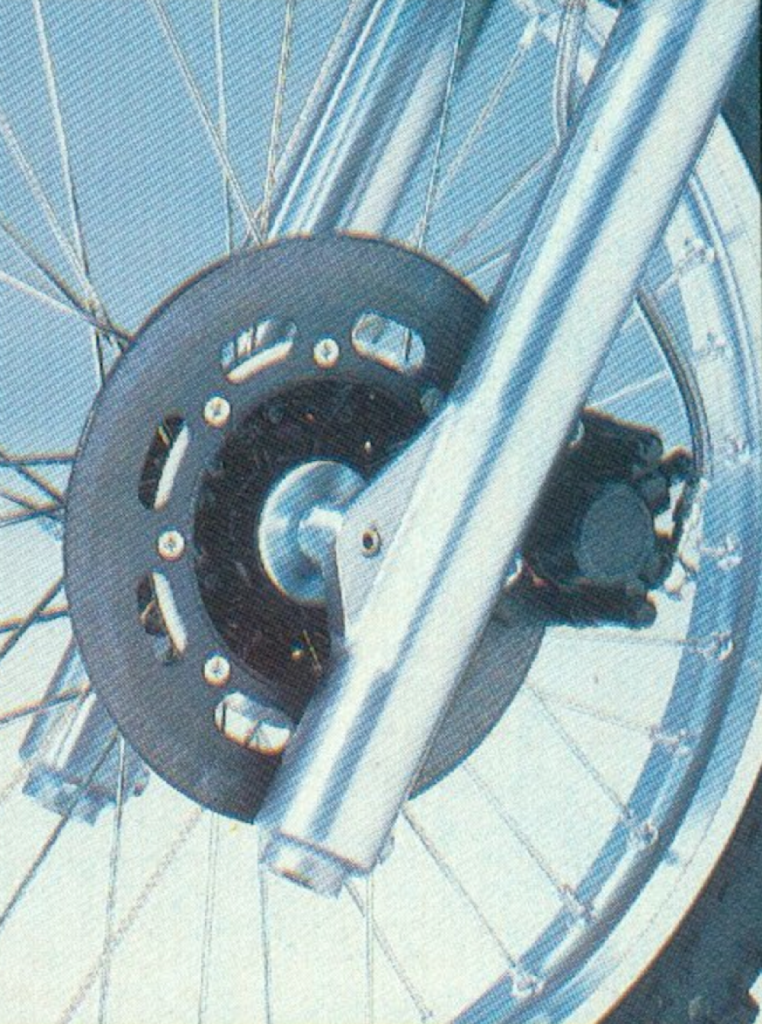

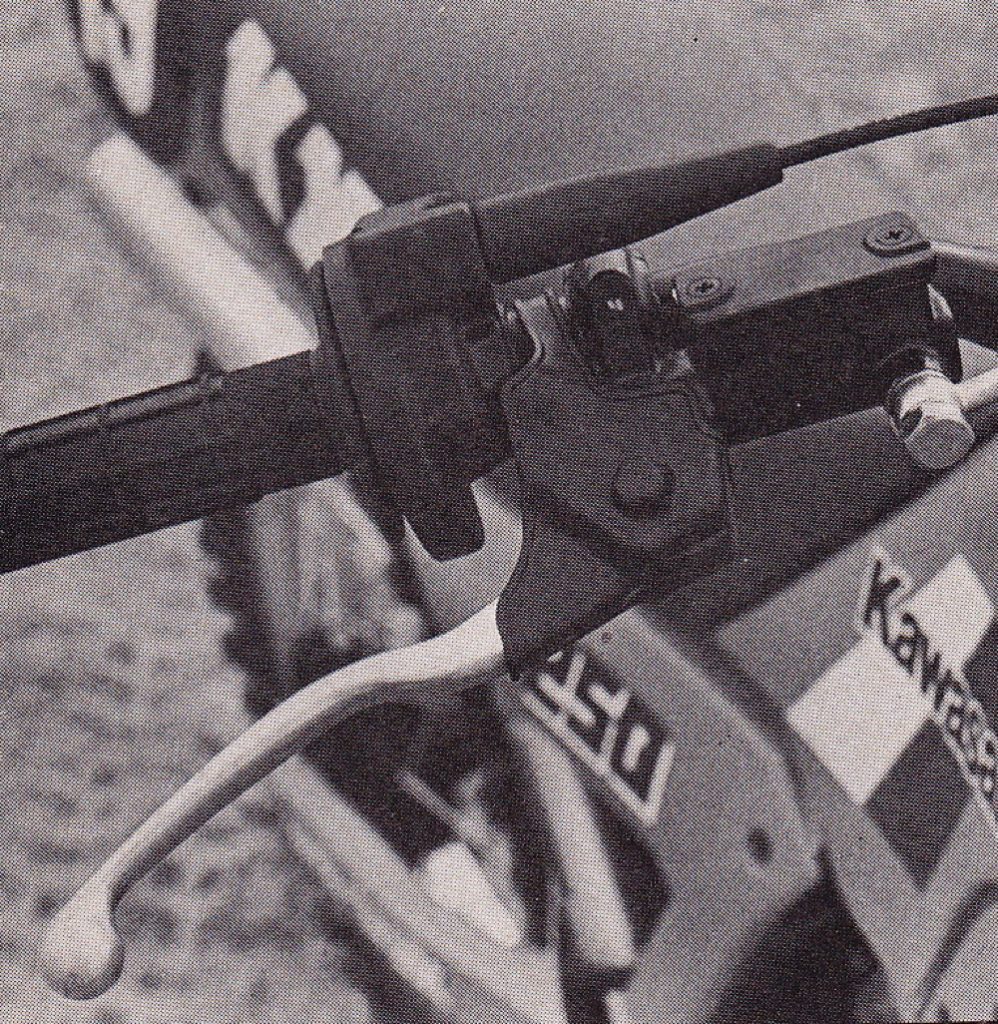

Kawasaki became the first major manufacturer to offer a front disc brake for motocross (unless you count Rokon’s oddball 340 MX-II from the mid-seventies) in 1982. In 1984, the single-piston unit on the KX offered good power, but inferior feel to the excellent dual-piston stopper found on the CR250R. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Kawasaki became the first major manufacturer to offer a front disc brake for motocross (unless you count Rokon’s oddball 340 MX-II from the mid-seventies) in 1982. In 1984, the single-piston unit on the KX offered good power, but inferior feel to the excellent dual-piston stopper found on the CR250R. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the track, the new KX offered a strong low-to-mid surge that rocketed the bike out of corners. Torque was up over ’83 and the bike offered the most midrange hit in the class. Top-end power was lacking, but the bike was fast from corner-to-corner. If you revved it out, it fell on its face, so it was better to short-shift it rather than trying to stretch out that last gear. Keeping it a gear tall and torqueing the bike around the track was the best method to make use of its powerband. As long as you did not try to scream it the KX was certainly competitive against its rivals.

Getting the 1984 Kawasaki KX250 to turn took total commitment and a lot of muscle. Photo Credit: Rich Cox

Getting the 1984 Kawasaki KX250 to turn took total commitment and a lot of muscle. Photo Credit: Rich Cox

While outright power was sufficient, the rest of the KX250 motor package was a bit lacking in 1984. Both the transmission and clutch were cranky and generally unpleasant to use. The gear ratios were well spaced for the power the bike made, but the shifting action left a lot to be desired. It started out notchy and only got worse as the clutch heated up. The clutch itself was incredibly suspect and unable to withstand even mild abuse. Once hot, the unit shuddered, chattered and struggled to keep the machine from taking off of its own accord.

Fools Gold: For 1984, Kawasaki dropped the cool gold coating from the wheels, swingarm and Uni-Trak linkage on all the KXs. the Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the chassis front, the new KX was just as flawed. Overall, the bike was very tall, long and awkward feeling. Compared to the other machines in the class, the KX felt much more like an Open bike than a cut-and-thrust 250. The ergonomics were odd as well, with funkily-shaped bars and footpegs that were mounted too far forward. Even with the new tank and lowered radiators, the bike retained a tall and tippy feeling than never went away. In the turns the KX was obstinate, cranky, and a ton of work. It was stubborn at turn in, hard to lay over and determined to stand up mid-corner. Getting it to change direction took perfect form, total commitment, and a fair amount of luck. Slack off or get out of position, and the big green meanie was likely to stand up and send you into a snow fence.

Pogo moto: The 43mm Kayaba forks on the ’84 KX offered 11.2 inches of grim travel. Insufficient damping in either direction caused them to dive under braking, bottom violently and rebound like a set of giant pogo sticks. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Pogo moto: The 43mm Kayaba forks on the ’84 KX offered 11.2 inches of grim travel. Insufficient damping in either direction caused them to dive under braking, bottom violently and rebound like a set of giant pogo sticks. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Usually, stubborn-corning bikes are good at speed, but the 1984 KX250 defied this convention. It was not a complete paint-mixer at speed like the Honda CR250R, but the KX liked to shake its head under deceleration. At speed, it imparted an unsettled feel that made the rider unsure of exactly what the bike was doing. It danced, wiggled and generally wandered wherever it pleased.

Strong low-end power made getting airborne easy on the ’84 KX250. Photo Credit: Tom Sapoto

Strong low-end power made getting airborne easy on the ’84 KX250. Photo Credit: Tom Sapoto

On the suspension front, the ’84 KX250 offered a set of 43mm Kayaba forks up front and a single KYB shock out back. The forks were non-cartridge (par for the course in 1984), offering 11.2 inches of travel and eight settings for compression adjustability. There was no rebound adjustment, but air could be added to each leg to fine-tune the ride.

Love it or hate it: Originally introduced on the 1981 KTMs, this unique rear fender/ number plate combo was adopted by Kawasaki in 1982. While it did make reading numbers easier, it gave the bike an odd appearance, left the exhaust exposed and stuck up so high that it whacked riders in the posterior. In 1985, this artifact of 80s motocross would be retired in favor of a much more conventional design. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Love it or hate it: Originally introduced on the 1981 KTMs, this unique rear fender/ number plate combo was adopted by Kawasaki in 1982. While it did make reading numbers easier, it gave the bike an odd appearance, left the exhaust exposed and stuck up so high that it whacked riders in the posterior. In 1985, this artifact of 80s motocross would be retired in favor of a much more conventional design. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the rear, the KX used its Uni-Trak linkage system to deliver 12 inches of travel through a single KYB damper. The shock featured a large remotely-located reservoir to prevent fading and featured four adjustments for compression and rebound damping. While overall travel was the same as 1983, the new silver swingarm and revised Uni-Trak featured an updated linkage curve to improve performance.

With its strong midrange burst, the KX could be fun to ride, but for racing, there were better choices available. Photo Credit: Moto Cross Magazine

With its strong midrange burst, the KX could be fun to ride, but for racing, there were better choices available. Photo Credit: Moto Cross Magazine

On the track, the new suspension proved better than 1983, but still not up to par with the best in the class. New stiffer fork springs and revised damping aimed to cut down on front end dive and bottoming, but neither proved particularly effective. The KX continued to pitch forward under braking and hammer to the stops on hard hits. Rebound damping was also too light, and the front of the bike actually bounced back up at the rider when bottomed.

Undersprung and underdamped, the Uni-Trak rear on the ’84 KX was only slightly better than its abysmal forks. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Undersprung and underdamped, the Uni-Trak rear on the ’84 KX was only slightly better than its abysmal forks. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The Uni-Trak rear was slightly better, offering a bit more control, but not enough bottoming resistance. Even medium-sized jumps left major burnt rubber marks on the underside of that ginormous fender/number plate combo. In the whoops, the rear wallowed and bounced as the overtaxed spring and inadequate damping struggled to keep the green machine in line. Even worse, that huge rear fender just loved to come up and whack you in the backside on rebound. At least it was not just ugly, it was functional!

While powerful, the front disc binder on the ’84 KX was far from trouble free. The unit required frequent bleeding and leaking hydraulic lines were common. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While powerful, the front disc binder on the ’84 KX was far from trouble free. The unit required frequent bleeding and leaking hydraulic lines were common. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the details front, the KX was a bit of a disappointment. The aforementioned King Kong rear fender made scoring easier, but looked odd, cracked easily, cost a ton to replace ($45 in 1984) and left the silencer exposed just waiting to roast some flesh. The new alloy front fender brace looked sano (in a Euro sort of way), but bent easily in a crash and was more an indictment of the KX’s grim plastic quality than any real attempt to up the trick quotient. The new pipe tucked in a little better, but continued to crack and leak chronically. The new frame was also of suspect quality and cracks at the welds were common. Broken spokes, cracked hubs and faulty swingarms were also noted by riders once the bikes had a few hours on them. While the front disc provided excellent power, the lines were prone to leaks and required constant maintenance. Maybe worst of all was part availability, which was by far the worst of the Big Four in 1984.

In many ways, the 1984 KX250-C2 stands as the demarcation line in Kawasaki’s 250 motocross program. The odd styling, quirky ergos and weird handling were soon to give way to much-improved machines. The arrival of the Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System in 1985 and the introduction of much more mainstream products would take the KX250 from an also-ran to a legitimate player in the 250 division. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In many ways, the 1984 KX250-C2 stands as the demarcation line in Kawasaki’s 250 motocross program. The odd styling, quirky ergos and weird handling were soon to give way to much-improved machines. The arrival of the Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System in 1985 and the introduction of much more mainstream products would take the KX250 from an also-ran to a legitimate player in the 250 division. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The 1984 season stands as a major turning point for Kawasaki’s motocross program. The KX60, KX80 and all-new KX125 took the world by storm in ‘84 and transformed Kawasaki from a background player to a headliner. The old-school KX250 and KX500 remained a step (or three) behind the competition, but better days were ahead. The 1985 season would see the arrival of the KIPS (Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System) and with it, much-improved machines. The 1984 KX250 was the last of the truly oddball Kawasaki deuce-and-a halfs.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com