For this installment of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at KTM’s all-new 250 motocrosser for 1998.

In 1998, KTM threw out the baby with the bath water and started from scratch with an all-new 250 design. While not a world-beater at the time, the strides taken by KTM in ’98 set the stage for the incredible growth the brand would enjoy over the next twenty years. Photo Credit: KTM

In 1998, KTM threw out the baby with the bath water and started from scratch with an all-new 250 design. While not a world-beater at the time, the strides taken by KTM in ’98 set the stage for the incredible growth the brand would enjoy over the next twenty years. Photo Credit: KTM

Today, KTM is one of the most successful brands in all of off-road motorcycling. They lead on the track with cutting-edge technology and lead in the showrooms with the most diverse lineup of offerings in the sport. Two-stroke or four, motocross or off-road, no brand covers as many bases as KTM.

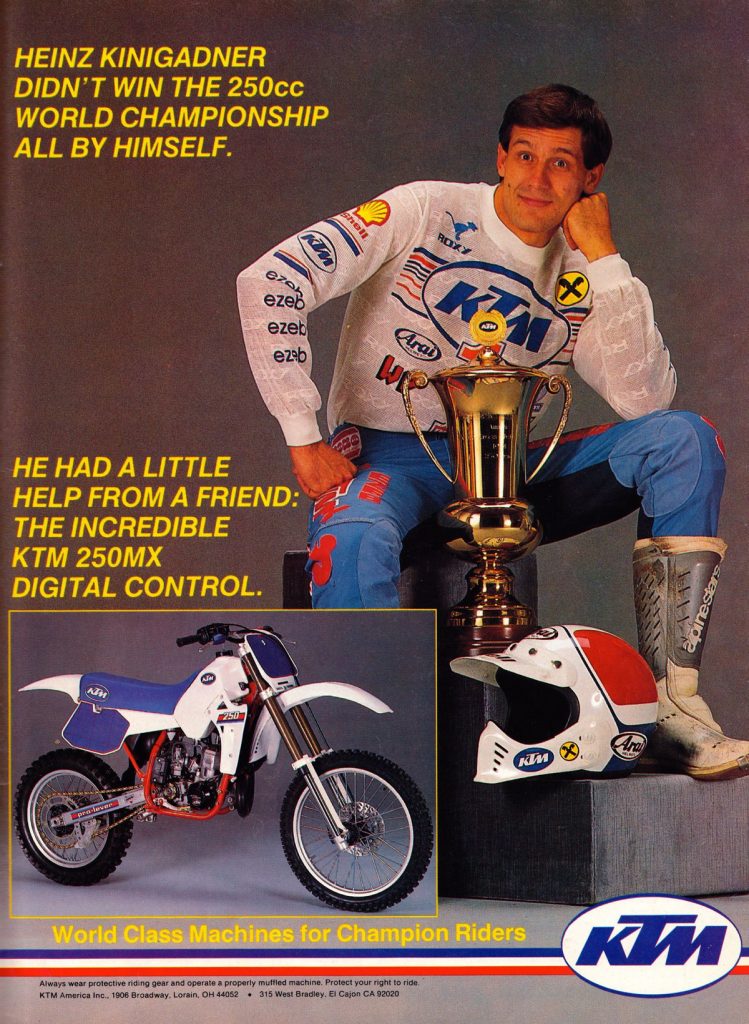

Kinigadner: While KTM was never much of a factor in US racing prior to the 2000s, it was certainly a player on the world stage. Several World Motocross titles in the seventies and eighties proved that the Austrians could indeed compete at the highest level with the proper level of support. Photo Credit: KTM

Kinigadner: While KTM was never much of a factor in US racing prior to the 2000s, it was certainly a player on the world stage. Several World Motocross titles in the seventies and eighties proved that the Austrians could indeed compete at the highest level with the proper level of support. Photo Credit: KTM

While today’s KTM is on top, it was not all that long ago that they were on the ropes. In the eighties and early nineties, KTM was more of a curiosity than a contender. Their bikes were often advanced (they were the first major brand to offer innovations like inverted forks), but out of step with the American market. Their chassis’ favored stability above turning and their motors were often more enduro than Supercross. This made them popular with the off-road set but held them back in the hyper-competitive motocross market.

Dark days: In 1991, KTM’s fortunes hit an all-time low with these odd red and minty-green bikes, and a bankruptcy filing. After a major restructuring, a new leaner and more nimble KTM would begin sowing the seeds of a global motocross superpower. Photo Credit: KTM

Dark days: In 1991, KTM’s fortunes hit an all-time low with these odd red and minty-green bikes, and a bankruptcy filing. After a major restructuring, a new leaner and more nimble KTM would begin sowing the seeds of a global motocross superpower. Photo Credit: KTM

In 1991, this lack of sales success came to a head, with KTM actually filing for bankruptcy proceedings. While the company survived, it was forced to restructure and divide their holdings into separate entities. Under this restructuring plan, the new company was divided into four discrete operations. One division handled their radiator business, another dealt with tool manufacturing, a third produced bicycles and the last handled the production of motorcycles. This new motorcycle division became KTM Sportmotorcycle AG and began the arduous task of rebuilding their tarnished reputation.

With more autonomy and less corporate red tape, the new KTM Sportmotorcycles was freed to try new ideas and push into niche markets not being served by the Big Four from Japan. The result was monster machines like the 550cc M/XC, and trick little minis like the 50cc SXR. “Nimble” was the new buzzword for KTM and they knew that the best way for them to succeed was to hit the Japanese where they weren’t.

By 1997, KTM was solidly on the rebound with a lineup of quirky, but moderately competitive designs. In the 250 class, the KTM offered strong power, but cranky handling and an odd feel. Photo Credit: KTM

By 1997, KTM was solidly on the rebound with a lineup of quirky, but moderately competitive designs. In the 250 class, the KTM offered strong power, but cranky handling and an odd feel. Photo Credit: KTM

In 1998, KTM brought this strategy to market with the most radically redesigned motocross machines in their history. All-new from the ground up, the 1998 lineup did away with nearly two decades of suspension design and thirty years of a tarnished reputation. The new machines combined cutting-edge technology with simplistic design and wrapped it in sleek bodywork. Lighter, leaner, and literally unlike anything else on the track at the time, the 1998 machines were a whole new type of KTM.

A switch from Marzocchi to WP for 1998 looked to alleviate the seal-life and reliability issues KTM owners had suffered from their forks in 1997. Photo Credit: KTM

A switch from Marzocchi to WP for 1998 looked to alleviate the seal-life and reliability issues KTM owners had suffered from their forks in 1997. Photo Credit: KTM

Of all the changes made for 1998, probably the most significant was in the new bike’s suspension design. Starting in the early eighties, motocross rear suspension had moved away from the simplicity of dual-shocks and toward the complexity of rising-rate linkage curves and beefy single dampers. The implementation of the rising-rate linkage allowed the engineers to tune the suspension to be supple on small bumps, while also retaining sufficient bottoming resistance on hard impacts.

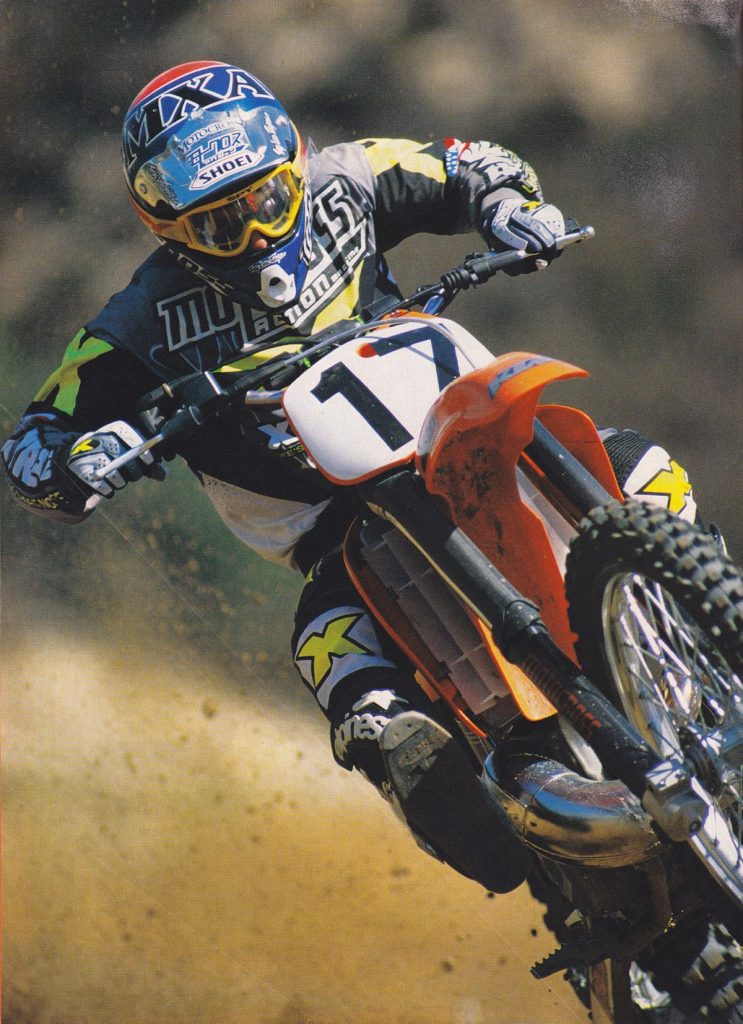

In 1998, the KTM 250SX was still very unique, but it finally offered ergonomics that mimicked the feel of the Japanese. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1998, the KTM 250SX was still very unique, but it finally offered ergonomics that mimicked the feel of the Japanese. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

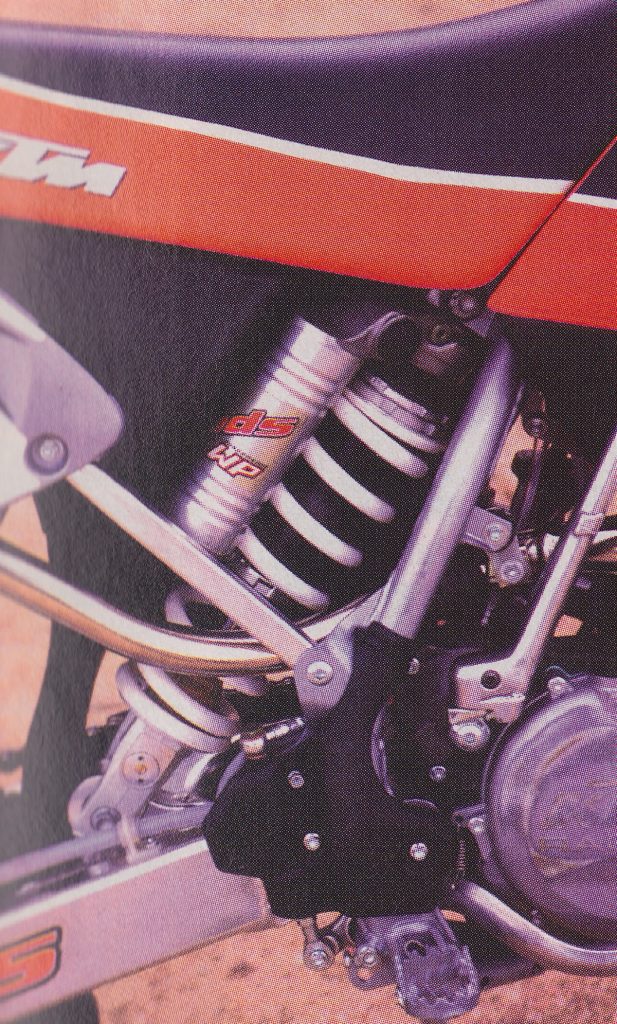

For 1998, KTM decided to abandon this proven technology in favor of an all-new design that combined the simplicity of the past with the technology of the future. Dubbed the “Progressive Damping System” (PDS), this new design did away with the rising-rate linkage completely and replaced it with a single damper bolted directly from the frame to the swingarm.

By far the biggest change made to the 250SX in 1998 was the adoption of WP’s new PDS (Progressive Damping System) “smart shock” to handle the damping duties. This new shock used two separate pistons to vary damping based on piston speed and position and allowed KTM to do away with a traditional rising-rate linkage. Photo Credit: KTM

By far the biggest change made to the 250SX in 1998 was the adoption of WP’s new PDS (Progressive Damping System) “smart shock” to handle the damping duties. This new shock used two separate pistons to vary damping based on piston speed and position and allowed KTM to do away with a traditional rising-rate linkage. Photo Credit: KTM

A decade earlier, boutique motorcycle manufacturer ATK had employed a similar system on their Austrian-powered and US-built machines to good effect. Through careful shock placement and expert valving design, ATK was able to mimic the performance of the traditional link-equipped machines while saving weight and shedding complexity. While never a mass-market success, ATKs were prized for their innovation and performance.

No Link: While the PDS shock was new technology, the idea of a link-less rear was anything but. Pretty much every machine produced prior to 1980 had used some variation of it and in the mid-eighties, Horst Leitner’s ATK had employed a setup very similar to the KTM’s on all of its models. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

No Link: While the PDS shock was new technology, the idea of a link-less rear was anything but. Pretty much every machine produced prior to 1980 had used some variation of it and in the mid-eighties, Horst Leitner’s ATK had employed a setup very similar to the KTM’s on all of its models. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For their new design, KTM took much of what ATK had accomplished and looked to improve on it by adding the latest in damping technology. In order to do this, the KTM engineers employed Dutch suspension manufacturer WP (KTM bought the former White Power suspension in 1995) to design an all-new type of shock that could compensate for the lack of linkage by allowing both speed and position-sensitive damping. In order to do this, WP spec’d a shock that incorporated two pistons and a special needle-valve. In this design, one damping piston was designated to react to the speed of fluid through the damper and the other was set up to respond to the position of the shock body on the shaft. By employing this special damping system and carefully selecting the angle of the shock in relation to the frame and swingarm, KTM believed they would be able to mimic the performance of a linkage, without the weight and packaging compromises required by traditional design. In literature, KTM labeled the PDS a “smart shock” and proclaimed it was the world’s first motocross shock with a “brain.”

In order to accommodate the new rear suspension, KTM had to design an all-new frame to match. Crafted out of tough chromoly steel, the new chassis featured a mixture of boxed and oval sections and a more aggressive geometry than previous KTMs. Photo Credit: KTM

In order to accommodate the new rear suspension, KTM had to design an all-new frame to match. Crafted out of tough chromoly steel, the new chassis featured a mixture of boxed and oval sections and a more aggressive geometry than previous KTMs. Photo Credit: KTM

In order to accommodate the new shock, KTM had to design an all-new chassis to match. The new frame was power-coated gray and fashioned out of tough chrome-moly steel. Using a boxed-section backbone and steeper geometry than 1997, the new frame was stronger and much more resistant to torsional flex than before. Bolted to the frame was an all-new swingarm that was beefed up, and like the frame, far stiffer than ’97. Finishing off the chassis package was a sano alloy subframe (removable), slick side-access airbox (one of the benefits of the offset shock) and slim and trim new bodywork. The bodywork, in particular, was a major upgrade, with a far less stodgy appearance and ergonomics that were finally designed for a human.

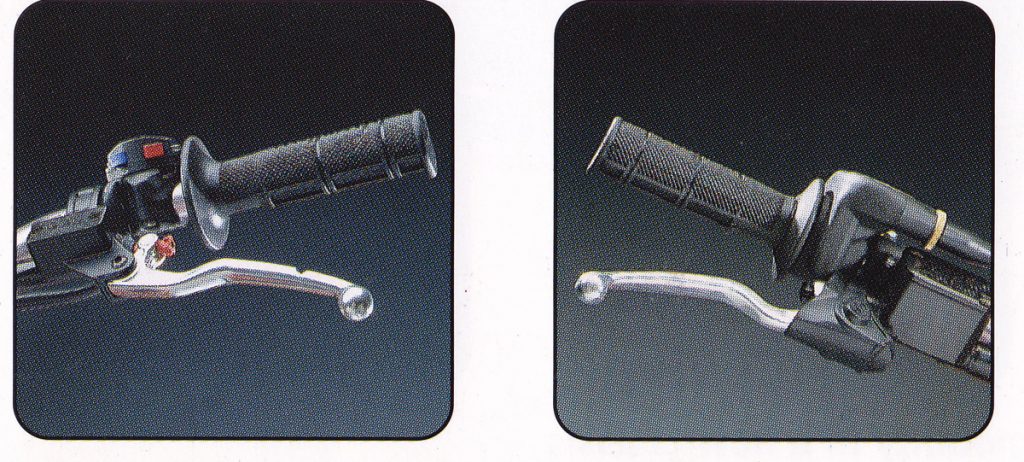

In 1998, KTM’s all-new 125SX received a hydraulic clutch for the first time. Unfortunately, the 250 would have to wait one more year for this convenient feature. Photo Credit: KTM

In 1998, KTM’s all-new 125SX received a hydraulic clutch for the first time. Unfortunately, the 250 would have to wait one more year for this convenient feature. Photo Credit: KTM

Up front, an all-new set of 50mm WP “Extreme” forks replaced the slightly problematic Marzocchi Magnum forks of ’97. As in ’97, KTM eschewed conventional wisdom by rejecting inverted forks in favor of a non-inverted design. In the mid-nineties, the jury was still out on which fork configuration worked best, with both KTM and Suzuki trying to resurrect this “old” technology.

An all-new cylinder for 1998 maintained the case-reed intake of ’97 and added a new ATAC-style resonance chamber to the exhaust port to boost low-end torque. Photo Credit: KTM

An all-new cylinder for 1998 maintained the case-reed intake of ’97 and added a new ATAC-style resonance chamber to the exhaust port to boost low-end torque. Photo Credit: KTM

In the motor department, KTM kept the bottom end of 1997 but bolted on a completely redesigned top-end for 1998. The new cylinder incorporated a Honda ATAC-style resonance chamber into the exhaust port for the first time and retained the case-reed configuration KTM had used since 1990. The exhaust add-on was coined the “KTM Torque Chamber” (KTC) and it was designed to boost low-end power by increasing head-pipe volume at low rpm. As a side benefit, KTM also claimed it helped “attenuate” the sound for a less obnoxious exhaust note.

All-new bodywork for 1998 offered improved ergonomics and the slimmest midsection in the class. Photo Credit: KTM

All-new bodywork for 1998 offered improved ergonomics and the slimmest midsection in the class. Photo Credit: KTM

On the track, the all-new ’98 KTM turned out to be a major improvement in some areas and a bit of a setback in others.

Chief among those setbacks had to be the 250’s new Brainiac shock. In spite of its trick internals and novel design, it turned out to do a pretty crappy job of taming the track. As delivered off the showroom floor, the PDS shock was overdamped and stiff to the point of punishing. On small stuff you felt every pebble, and on big hits, it crashed into a wall of damping mid-stroke. It was incredibly harsh in action and unloved by nearly everyone. At the press launch of the ’98 KTMs, their engineers warned that the shock would require a lengthy break-in to smooth out its action, but by all accounts, that smoothing never really happened.

The new chassis for 1998 offered much-improved turning over previous KTMs, but that came at the expense of some straight-line stability. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The new chassis for 1998 offered much-improved turning over previous KTMs, but that came at the expense of some straight-line stability. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Up front, things were rosier, as the 50mm WP Extreme forks did a great job of offsetting the shock’s many problems. They offered 11.8” of travel and adjustments for compression and rebound damping (weirdly, with one leg handling the compression adjustment and the other handling the rebound settings). Their performance was plush on the small stuff and sufficiently firm on hard hits. Pros still found the conventional forks too flexy, but mere mortals approved of their compliance. The new WP forks also seemed to maintain their performance longer than previous KTM conventional offerings. Seal life was much improved over the old Marzocchi units and the internals seemed to last longer before requiring a rebuild. Overall, the WP Extremes were rated either first or second in the majority of magazine shootouts in ’98.

The redesigned 249cc case-reed motor on the ’98 250SX pumped out a wide, but mellow spread of ponies. There was very little burst and not much power in reserve. This worked well on dry and slick tracks but put the orange bike at a serious handicap when the conditions were deep and loamy. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The redesigned 249cc case-reed motor on the ’98 250SX pumped out a wide, but mellow spread of ponies. There was very little burst and not much power in reserve. This worked well on dry and slick tracks but put the orange bike at a serious handicap when the conditions were deep and loamy. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the motor front, the KTM’s new 249cc motor turned out to be a pretty big disappointment. In 1997, the KTM had offered a powerful-mid-and-up motor that was more than capable of running with the Japanese competition. It was soft down low, but blistering on top. For 1998, the KTM engineers tried to boost the bike’s torque, without sacrificing its strong top end pull.

The 1998 crop of 250s offered a diverse field of competitors vying for your hard-earned cash. Both KTM and Suzuki featured conventional forks and Honda was still making waves with its spacy new alloy frame. In the end, none of them were capable of besting the Kawasaki’s unbeatable combination of brawny power, sure handling and solid suspension performance. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The 1998 crop of 250s offered a diverse field of competitors vying for your hard-earned cash. Both KTM and Suzuki featured conventional forks and Honda was still making waves with its spacy new alloy frame. In the end, none of them were capable of besting the Kawasaki’s unbeatable combination of brawny power, sure handling and solid suspension performance. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Unfortunately, the new cylinder and power valve design only accomplished half of this plan. The new motor was smooth off the bottom, pleasant in the middle, and mild on top. The powerband was wide, but utterly lacking in any pizzazz. There was no hit, no burst, and absolutely none of the shrieking top-end power of ’97. If anything, it most resembled one of KTM’s enduro motors. This meant it was easy to ride and great on slick tracks, but slow-feeling everywhere else. For motocross, more ponies were a must.

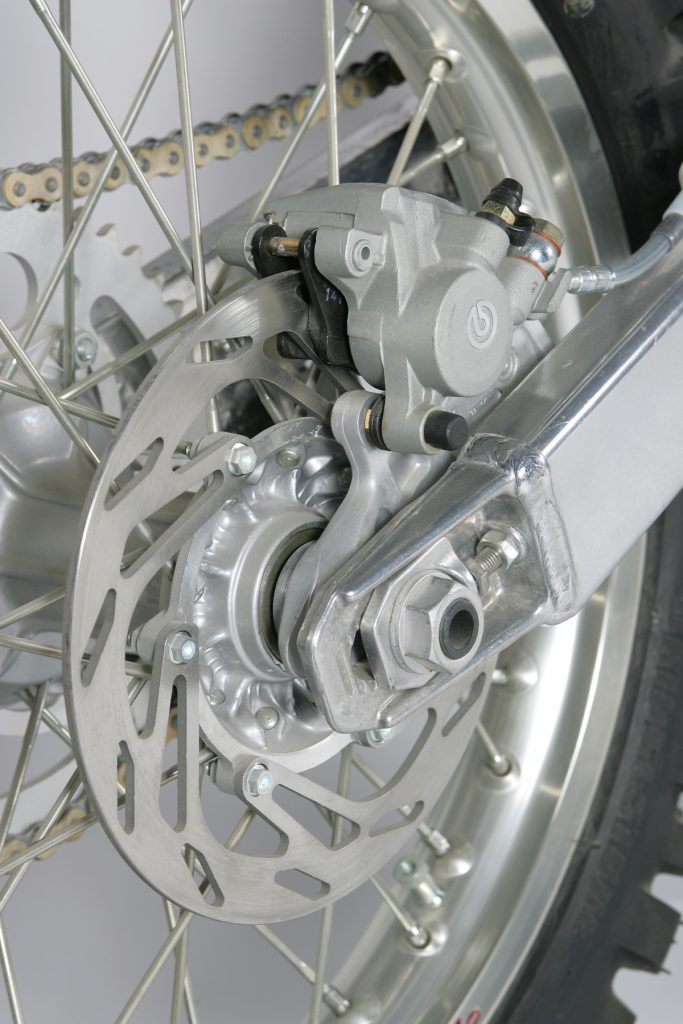

In 1998, KTM had not yet captured its reputation for the best brakes in the business. Both the front and rear discs were rated below those offered from Japan. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1998, KTM had not yet captured its reputation for the best brakes in the business. Both the front and rear discs were rated below those offered from Japan. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In the chassis department, the new KTM turned out to be a substantial improvement over previous Austrian efforts. The stiffer frame and steeper geometry finally delivered a KTM that could turn. Pilots no longer needed to search the track looking for a rut or berm to bounce off of. Instead, they could dive to the inside and count on the front wheel to hold its line through the turn.

The mid-nineties saw the conventional fork make a comeback with brands like WP, Marzocchi and Showa offering updated versions of this classic design. In 1998, both the KTM’s WP and the Suzuki’s Showa forks actually outperformed the inverted competition, but outside forces like marketing pressure and the whims of the race teams meant the days of the conventional fork were numbered. By 2000, all the brands would be back to inverted designs. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The mid-nineties saw the conventional fork make a comeback with brands like WP, Marzocchi and Showa offering updated versions of this classic design. In 1998, both the KTM’s WP and the Suzuki’s Showa forks actually outperformed the inverted competition, but outside forces like marketing pressure and the whims of the race teams meant the days of the conventional fork were numbered. By 2000, all the brands would be back to inverted designs. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

For 1998, KTM knocked a full 11 pounds off of their 250-class offering. The lighter weight and slimmer ergonomics helped make the new KTM more nimble on the track and more capable in the air. Here, Dirt Rider’s Rich Taylor demonstrates the KTM’s newfound aerial prowess. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

For 1998, KTM knocked a full 11 pounds off of their 250-class offering. The lighter weight and slimmer ergonomics helped make the new KTM more nimble on the track and more capable in the air. Here, Dirt Rider’s Rich Taylor demonstrates the KTM’s newfound aerial prowess. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

Unfortunately, the flip side of this newfound nimbleness was a very Honda-like wobble when coming down from speed. In stock condition, the new PDS shock jacked up the rear of the KTM like a Funny Car. It sat high in the travel and never really settled like a traditional linkage rear end. This, combined with the mis-matched suspension settings and steep steering-head angle, gave the KTM a mighty case of the shakes. Considering most KTMs to this point handled like freight trains, this was a singularly new experience for the Austrian aficionados.

In addition to being slow, the KTM’s new motor offered notchy shifting and a weak clutch. At least the new graphics looked cool and the new pipe was resistant to corrosion. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In addition to being slow, the KTM’s new motor offered notchy shifting and a weak clutch. At least the new graphics looked cool and the new pipe was resistant to corrosion. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

One of the bright sides on the new 250SX was certainly its new bodywork. The all-new plastic ditched the slightly odd butterscotch color of ’97 in favor of a much deeper hue of orange. The new “Z-shaped” shrouds were stylish and the updated layout was the slimmest in the class. For once, the ergonomics were even good, with very little of the traditional “Euro” feel that had put off American riders for two decades. Only the absurdly hard saddle remained to remind Billy Bob that this machine came from Mattighofen, instead of Tokyo.

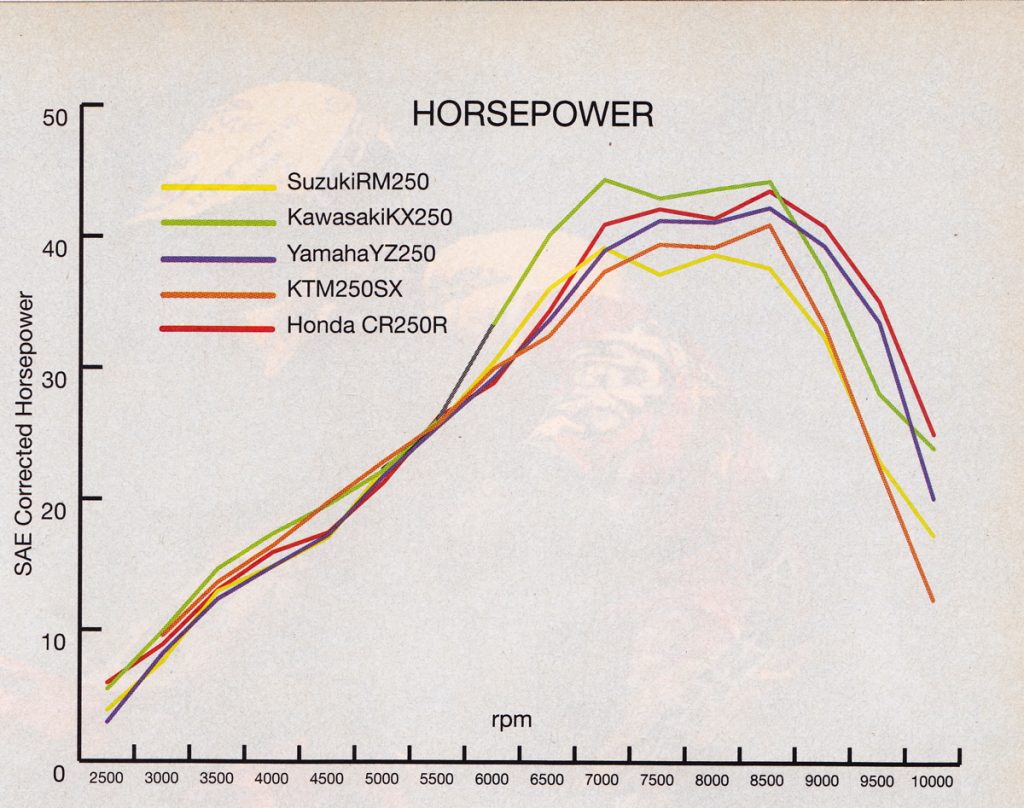

In the horsepower wars of 1998, it really was no contest. The Kawasaki offered the brawniest hit and most power by a wide margin. On top, the CR pulled ahead, but at every other point on the curve, the green machine romped on the competition. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the horsepower wars of 1998, it really was no contest. The Kawasaki offered the brawniest hit and most power by a wide margin. On top, the CR pulled ahead, but at every other point on the curve, the green machine romped on the competition. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the detailing side, the new KTM was a step forward over previous Austrian efforts, but still a tick behind the Japanese in some categories. On the plus side were its strong alloy bars (the Japanese were still shipping their bikes with steel butter-bars in ’98), trick side-access airbox (one of the benefits of the side-saddle PDS shock), maintenance-free plated exhaust pipe (gaudy, but no more rust), durable and long-lasting graphics (way tougher than the competition) and lack of a linkage to maintain (woo hoo).

Pretty Damn Stiff: KTM touted their new PDS damper as the first shock with a “brain,” but most riders found it more confused than crafty. Too stiff, too harsh, and nearly impossible to set up properly, the new design won praise for ease of servicing, but little else. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Pretty Damn Stiff: KTM touted their new PDS damper as the first shock with a “brain,” but most riders found it more confused than crafty. Too stiff, too harsh, and nearly impossible to set up properly, the new design won praise for ease of servicing, but little else. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the bummer side were its bizarre assortment of fasteners, self-ejecting shock bolts (watch them like a hawk, or be prepared to own a low-rider), easily-frayed seat cover, lackluster brakes, and fragile clutch. In 1998, the 250SX did not get the benefit of the new 125’s hydraulic unit and had to make do with traditional cable actuation. While this was not really a handicap, its sub-par plate life was.

In 1998, KTM made the bold decision to go their own way and introduced a radically new 250 motocrosser. The redesigned 250SX provided a less European feel, while still offering a uniquely KTM experience. While it was far from a world-beater, it did show that KTM was not ready to fade into the heap of retired European marques like Maico, Bultaco and CZ. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1998, KTM made the bold decision to go their own way and introduced a radically new 250 motocrosser. The redesigned 250SX provided a less European feel, while still offering a uniquely KTM experience. While it was far from a world-beater, it did show that KTM was not ready to fade into the heap of retired European marques like Maico, Bultaco and CZ. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Overall, the 1998 KTM 250SX proved to be a major step forward for the brand, but not the dragon-slayer many in Austria had hoped for. Packed with innovation and clearly willing to go its own way, the new 250SX proved both more conventional, and more eccentric than any KTM before. With its no-link “smart shock” and conventional forks, it provided a unique alternative to the traditional Japanese offerings, while still catering to the moto mainstream with better ergonomics and sharper handling. Its motor was still more tree-dodger than berm-buster, but for someone looking to march to the beat of a different drummer, the 1998 KTM offered the most compelling Austrian argument since the days of John Penton.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com