For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki’s ripping super-mini for 1996, the KX100.

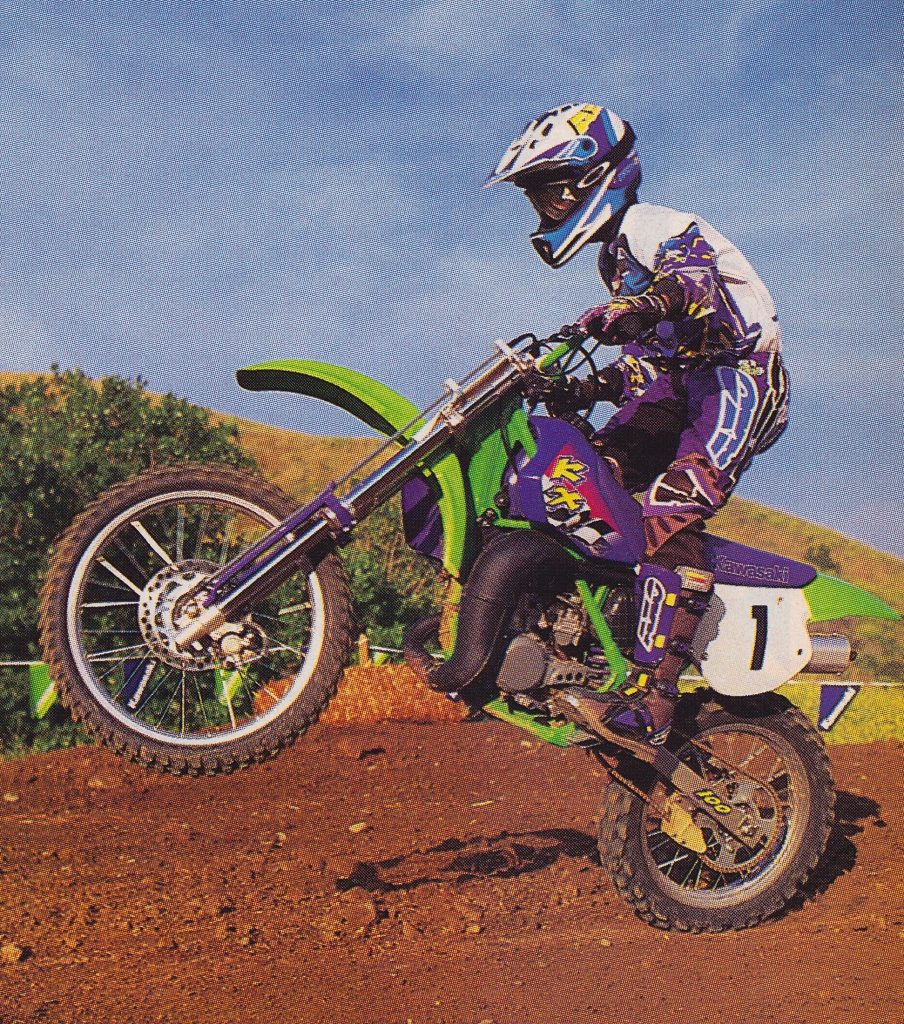

In 1995, Kawasaki bumped up the displacement on their KX80 Big Wheel and made life easier on every parent looking to race the Super Mini division. The new KX100 was the perfect in-between machine for riders too big for an 80, but not quite ready for a full-sized 125. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1995, Kawasaki bumped up the displacement on their KX80 Big Wheel and made life easier on every parent looking to race the Super Mini division. The new KX100 was the perfect in-between machine for riders too big for an 80, but not quite ready for a full-sized 125. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

If there is one word that can sum up motocross in the early to mid-nineties, that word would have to be “purple”. The color of royalty for centuries, this combination of red and blue hues made its way into all facets of the sport during the reign of 90210 and Beavis and Butthead. Gear, graphics, casual wear, and motorcycle bodywork were all dipped in this regal shade for a short time before the fad was over as swiftly as it had begun.

In 1987, Kawasaki became the first manufacturer to offer a “Big Wheel” mini since the heyday of the 100 class in the 1970s. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1987, Kawasaki became the first manufacturer to offer a “Big Wheel” mini since the heyday of the 100 class in the 1970s. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For Kawasaki, this purple craze reached its zenith with the introduction of the 1996 KX lineup. All the machines were only mildly refreshed for ‘96, but they certainly looked new with their grape-flavored bodywork and bold Barney graphics. Some people loved the new look and others just scratched their heads, but there was no mistaking their unique appearance.

The introduction of the all-new CR80R Expert for 1996 brought competition to the Super Mini class for the first time. Blazing fast, but hard to ride, the CR was more advanced than the KX but not necessarily a better mini. Photo Credit: Honda

The introduction of the all-new CR80R Expert for 1996 brought competition to the Super Mini class for the first time. Blazing fast, but hard to ride, the CR was more advanced than the KX but not necessarily a better mini. Photo Credit: Honda

In the case of the KX100, this new look was certainly the most dramatic change that Kawasaki had on tap for 1996. A new model in 1995, the KX100 had developed as a natural progression of Kawasaki’s “Big Wheel” program. Originally introduced in 1987, Kawasaki’s KX80 Big Wheel had provided the perfect stepping stone for riders too large for a traditional 80 but not quite big enough for a full-size 125. Featuring larger wheels (hence the name), a longer wheelbase, and upgraded suspension, the KX80 Big Wheel filled a void left by the death of the 100 class in the early 1980s.

By adding 17cc to the KX80’s 82cc power plant, Kawasaki punched up the torque and addressed the green (purple) mini’s greatest weakness. With its newly-found grunt, the KX100 offered a smooth and broad (for a mini) powerband that was far easier to manage than the hard-hitting Honda. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

By adding 17cc to the KX80’s 82cc power plant, Kawasaki punched up the torque and addressed the green (purple) mini’s greatest weakness. With its newly-found grunt, the KX100 offered a smooth and broad (for a mini) powerband that was far easier to manage than the hard-hitting Honda. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

By 1994, the KX80 Big Wheel had developed into a potent and highly advanced mini racer. Like its big brothers, it featured a stout steel perimeter frame, inverted forks, dual disc brakes, and a powerful liquid-cooled two-stroke motor. With its modest 82cc displacement and without the benefit of a power valve, its powerband remained rather narrow and peaky, but it was certainly competitive in the right hands.

On the track the KX100’s comfortable chassis and broad power made shredding berms a piece of cake in 1996. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1995, Kawasaki looked to expand the appeal of their big-wheeled racer by broadening the power of their tweener-sized mini. To do this, Kawasaki went the tried and true muscle car route and bumped up the displacement from 82cc to a full 99cc by punching out the bore 4.5mm. At the time, displacements up to 112cc were allowed in the “Super Mini” division so many KX80 Big Wheel riders had already gone this route through aftermarket means. By taking care of this at the factory, Kawasaki further cornered the Super Mini market by offering a race-ready alternative right off the showroom floor.

In spite of looking similar to the units found on its larger siblings, the 36mm Kayaba inverted forks employed on the KX100 featured heavier steel construction and less-costly non-cartridge internals. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Compared to the standard KX80, the new KX100 was taller, longer and heavier overall. The wheels were two inches larger front and rear and the swingarm was extended 1.2 inches. This added up to a 1.2-inch increase in both wheelbase and seat height on the KX100. Up front the 100 featured a 36mm inverted Kayaba fork that offered increased rigidity over the 38mm conventional TCV Kayaba fork employed on the standard KX80. Overall wheel travel remained unchanged between the two, with both offering 10.8 inches of movement front and rear. The combination of the larger motor, suspension and chassis components added up to a seven-pound increase in weight for the KX100 over the KX80.

Not as snappy down low as the RM, or as frantic on top as the CR and YZ, the KX’s 99cc mill took the Goldilocks approach to mini power in 1996. Broad, smooth, and easy-to-manage, the KX was perfect for novices but perhaps a bit mellow for the Ricky Carmichaels of the world. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

For 1996, the changes to the KX100 were fairly minimal. Aside from the dramatic new look, the most significant upgrades were a slightly longer silencer (claimed by Kawasaki to reduce noise without sacrificing any power), a KX125 front master cylinder (complete with sight glass and, hopefully, less mushy performance), and a new gas cap (for improved venting). Other than these admittedly minor upgrades, the KX100 was the same machine it had been in 1995.

In 1996, there were two very distinct flavors available to Super Mini racers. For fast kids, the CR80R Expert offered potent top-end power and a great deal of suspension adjustability, but its powerband was peaky and its suspension was unbalanced. In the case of the KX100, the motor was mellower and less exciting, but it was easier to keep on the pipe and better-suspended out of the crate. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

One significant thing that did change for 1996 was the addition of actual competition in the Super Mini class. After eight years of having the big-wheeled division all to themselves, Kawasaki came under fire for the first time with the introduction of Honda’s all-new CR80R Expert. Slightly larger in size than the KX100, the CR80R Expert featured a smaller motor, but an all-new chassis and more advanced suspension. Unlike the inverted units found on the KX, the CR’s new 37mm Showa USD forks featured adjustments for both compression and rebound as well as more sophisticated cartridge internals to handle the damping.

The move to purple for the tank, shrouds and fork guards in 1996 was a love-it or hate-it affair. Today, it certainly makes these ‘96 KXs stand out, but at the time many people thought Kawasaki had gone a bit too far with the grape coloring. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the track, the additional 17cc paid major dividends in the rideability department. Compared to the standard KX80, the 100 picked up sooner and pulled stronger through the midrange. On top, it may have actually offered slightly less pull than the 80, but the tradeoff was much easier to manage power delivery. Off the line and out of corners, the 100 required less clutch abuse and was far easier to keep on the pipe. Compared to the CR80R expert, the KX100 offered a serious torque and rideability advantage, but significantly less top-end power. For experts with the skill to keep it on the pipe, the CR offered blistering performance, but it was much harder to ride and tricky to keep from bogging between gears. For most riders, the broad and smooth power of the KX100 was superior to the potent, but pipey Honda.

The KX100’s 36mm Kayaba front forks lacked cartridge internals and some of the CR’s adjustments, but it outperformed them on the track. Proper spring selection and careful setup put these forks in the ballpark for most riders below the expert division. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the suspension end of things, the Kawasaki’s 36mm inverted Kayaba forks looked very similar to their larger cousins but suffered from several cost-cutting measures. Externally, the outer tubes were fashioned out of steel instead of lightweight aluminum and internally they featured an old-school damper-rod system instead of the more advanced cartridge damping of the CR. Out back, the KX used a more up-to-date fully-adjustable Kayaba shock with 4 settings for rebound and 16 for compression damping.

Like the forks, the Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak linkage and Kayaba rear shock provided smooth action and plush performance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In terms of performance, the KX100’s suspension was considered excellent for its targeted market. For really fast guys and kids above 120 pounds the forks and shock were a bit soft, but most mini pilots of average size and speed loved their smooth action. Throttle jockeys also complained of some kicking from the shock when charging whoops, but kids of lesser skill did not notice.

The KX100’s stout perimeter frame was the most advanced chassis in the mini class in 1996. It provided sure handling and excellent turning, mixed with a bit of high-speed twitchiness. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Interestingly, the more advanced components on the Honda were actually rated below the old-fashioned ones found on the Kawasaki. The Honda’s forks were knocked for their slightly harsh action on choppy terrain and overall lack of plushness compared to the KX. The shock was also dinged for its underdamped action and propensity to hang down in the stroke. This made the bike unbalanced and hindered its handling overall. In spite of being older and less sophisticated, the Kawasaki’s more careful setup gave it the superior suspension package out of the crate.

While the KX100’s powerband was praised for its flexibility and ease-of-use, its transmission drew raspberries (or should it be grapes?) for its notchy action. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the handling front, the KX100 was a real shredder in 1996. With its flat layout, well-behaved suspension and stout chassis, the KX was the king of the inside line. On tight tracks, the KX could cut over, under and around most of the other minis on the track. At high speed, though, it became a bit of a handful. Headshake was not “come to Jesus” bad, but it twitched far more than most ten-year-olds would have probably liked. Compared to the unbalanced and pipey Honda, the KX was less exciting but far easier to go fast on.

In 1996, Kawasaki offered mini pilots a great race-ready option for the Super Mini class right off the showroom floor. The KX100 was fast (not blazing, but fast enough), well suspended, and turned on a dime. It was a solid package that was great in 1996 and good enough to underpin Kawasaki’s mini offerings for the next seventeen years. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1996, Kawasaki offered mini pilots a great race-ready option for the Super Mini class right off the showroom floor. The KX100 was fast (not blazing, but fast enough), well suspended, and turned on a dime. It was a solid package that was great in 1996 and good enough to underpin Kawasaki’s mini offerings for the next seventeen years. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1996, the Super Mini division finally got some competition and the old veteran of the class took the rookie on and came out on top. Broader, smooth, and more polished, the KX100 was not as blisteringly fast as the all-new CR80R Expert, but it was far more race-ready out of the crate. Unless you were Ricky Carmichael or James Stewart, it offered more than enough performance out of the box. For a generation of kids who had grown up on green, it was the perfect stepping stone to the big leagues.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram – @TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com