Today, Suzuki’s motocross program is a mere shadow of its former glory. Once the owners of ten straight 125 World Motocross Titles in the seventies and early eighties, the manufacturer from Hamamatsu has morphed into the purveyor of discounted bikes and stale technology.

Never the biggest of the “Big Four,” Suzuki had always been a scrappy operation that eked out surprising results from a modest budget. In the late sixties, they had been the first of the Japanese manufacturers to actually get serious about motocross and the results were a run of World Motocross Titles that dwarfed their Nipponese competition. They won in the 500s, the 250s, and eventually, the 125s as well. With riders like Roger De Coster, Joël Robert, and Gaston Rahier at the controls, the works Suzukis of the 1970s were the most dominant machines in motocross.

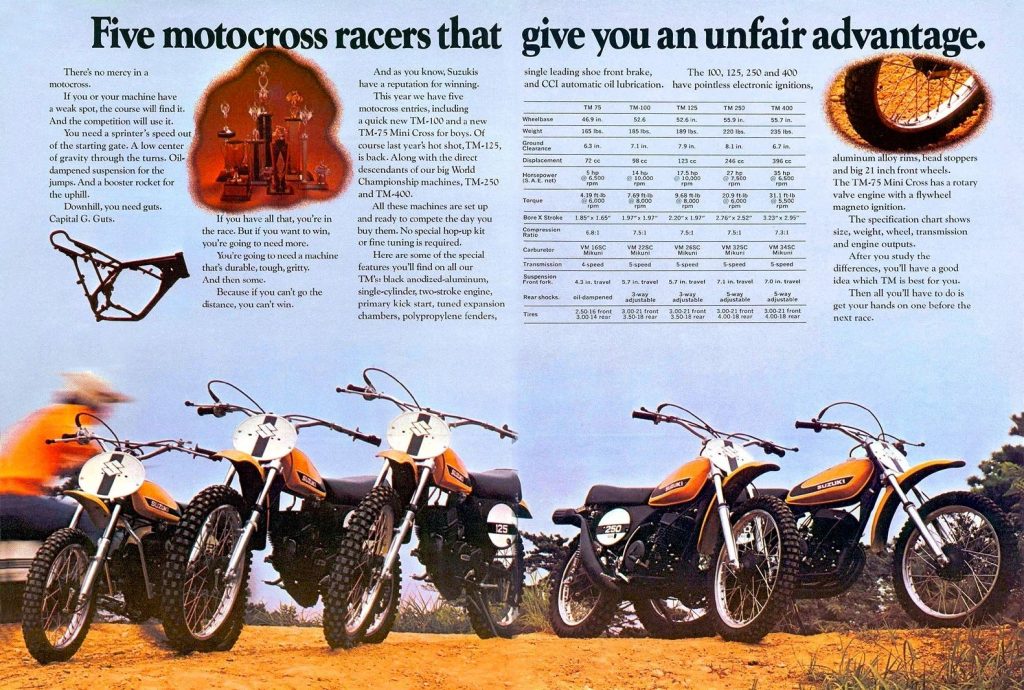

While the works machines of De Coster and Robert cleaned up on the track, the production machines offered to the public were somewhat less successful. In 1968 Suzuki released its first production motocrosser, the TM250. Basically a full works replica of their RH67, this first TM was produced in very limited numbers (only 200 were produced) and offered very modest performance. Even by the standards of 1968, this first TM left much to be desired and Suzuki shelved the project at the end of the year.

Suzuki’s early motocross lineup was broad but mostly unimpressive.

Four years later, Suzuki returned to the production motocross market with the all-new TM400 Cyclone. Featuring a 396cc two-stroke single, the Cyclone was strong on power but weak on literally everything else. Infamous for its evil handling, the TM400 became one of the true horror machines of early seventies moto as “injury forces sale” became an all-too-common sighting in used Cyclone listings from coast to coast.

Eventually, Suzuki tamed much of the evilness out of the TM400 and added far less malevolent offerings in the 250 and 125 class. Neither the TM250 Champion or TM125 Challenger turned out to be Elsinore beaters, but they were pleasant enough machines for the clubman racer on a budget.

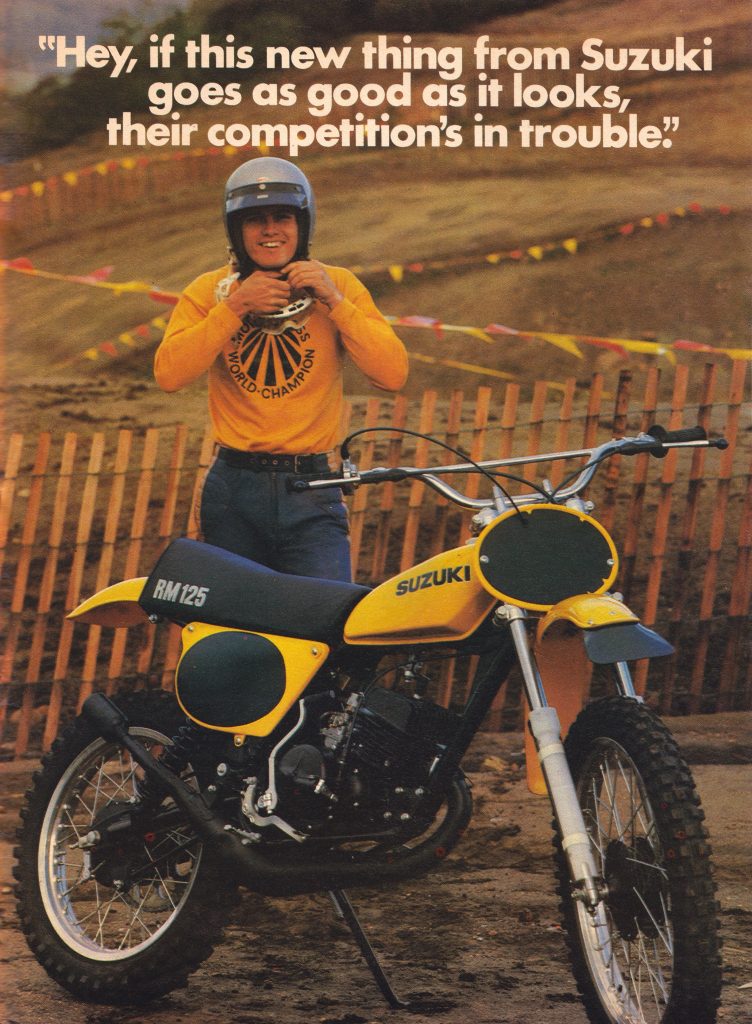

In 1975, this new RM125 was the machine that launched a thousand paper routes.

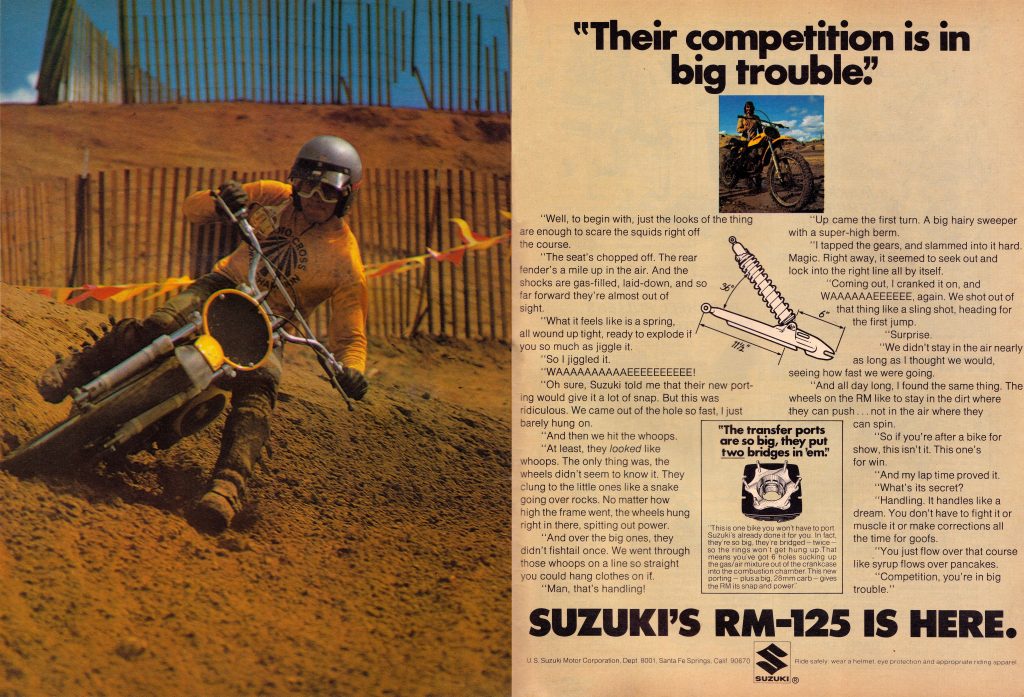

In 1975, all that changed with the introduction of the first in a line of machines that would change the face of the sport for the remainder of the decade, the all-new RMs. Unlike the TMs, which shared little more than a color scheme with their works cousins, the new RMs were legitimate works replicas. With long-travel laid-down shocks, stout chassis, and powerful motors, the new RMs would come to dominate much of motocross in the mid-to-late seventies. In 1975, the first of these machines made its debut in the form of the all-new RM125. At the time, its radically laid down shocks and racy styling signaled that this new machine had more serious intentions than the budget-racer TM125. Offering significantly more travel and a slightly stronger motor, this first RM was more of a precursor to greatness than an absolute game changer. Sharing most of its motor components with the outgoing TM, the new RM was not the powerhouse that the new mono-shocked and reed-valved YZ was, but it did offer excellent rear suspension and a great handling chassis.

While the motor was not a radical departure from the existing TM125, the new long-travel shocks and more aggressive porting gave the RM a far more serious character than its less expensive stablemate.

While this new RM125 did not overshadow the competition in 1975, it did set the stage for the watershed year of 1976 when Suzuki would release a full lineup of completely new RM machines that would take the sport by storm. The all-new RM125A, RM250A, and RM370A offered radically new reed-valve motors, long-travel suspension, svelte chassis, and works styling. Sexy, fast, and finely finished, these new RMs were everything the average racer could ask for in a production machine at the time. After half a decade of mediocrity, Suzuki’s production machines had finally arrived and that turnaround started in 1975 with a pair of long-travel shocks and 123cc of pin-it-to-win-it passion from the little brand that could.