For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki’s all-new KX250 for 1987.

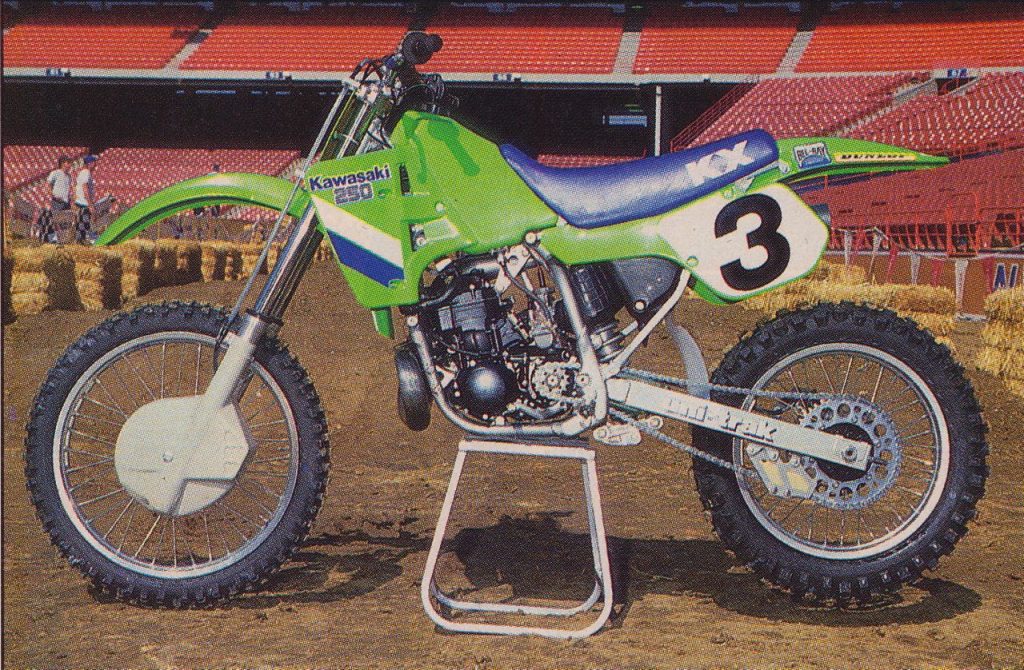

All-new from the ground up, Kawasaki pulled out (nearly) all the stops to capture motocross dominance in 1987. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The eighties were an era of great change in motocross. Manufacturers often totally revamped their lineups after only a single season and one year’s critical darling could easily turn out to be next year’s critical flop. In 1986, that darling had turned out to be the Honda CR250R. After a lackluster outing in 1985, the CR had come roaring back to dominate the class with works-like suspension, a powerful new motor, and sano looks. The CR dominated in the magazines and on the track, taking every major shootout and both AMA 250 titles with Rick Johnson at the controls.

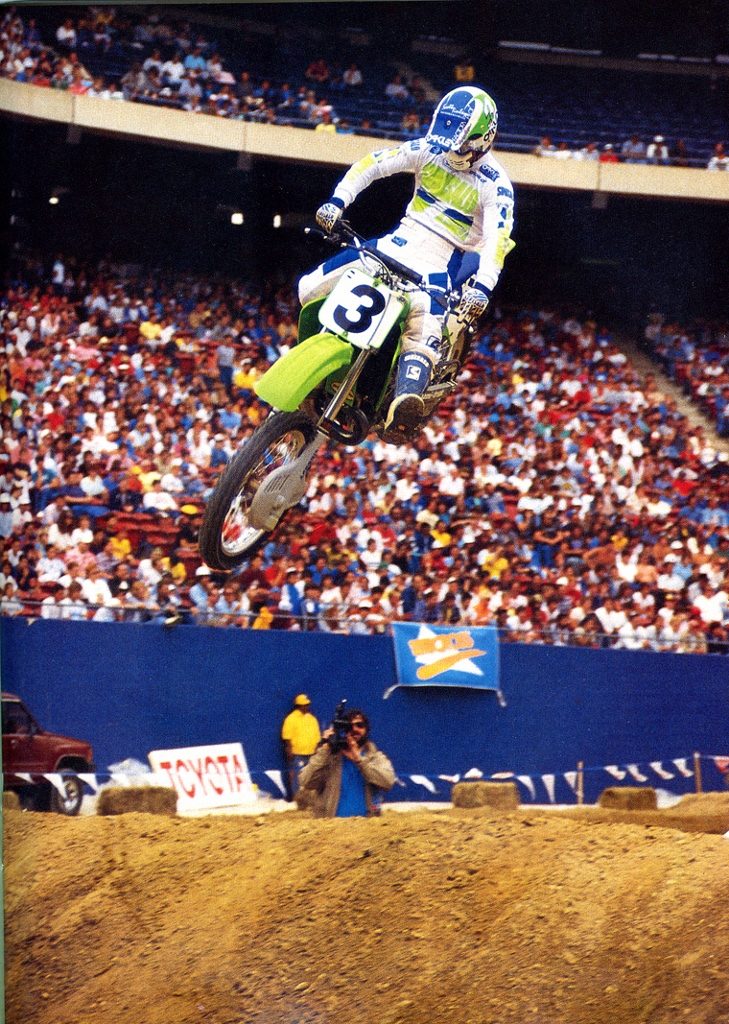

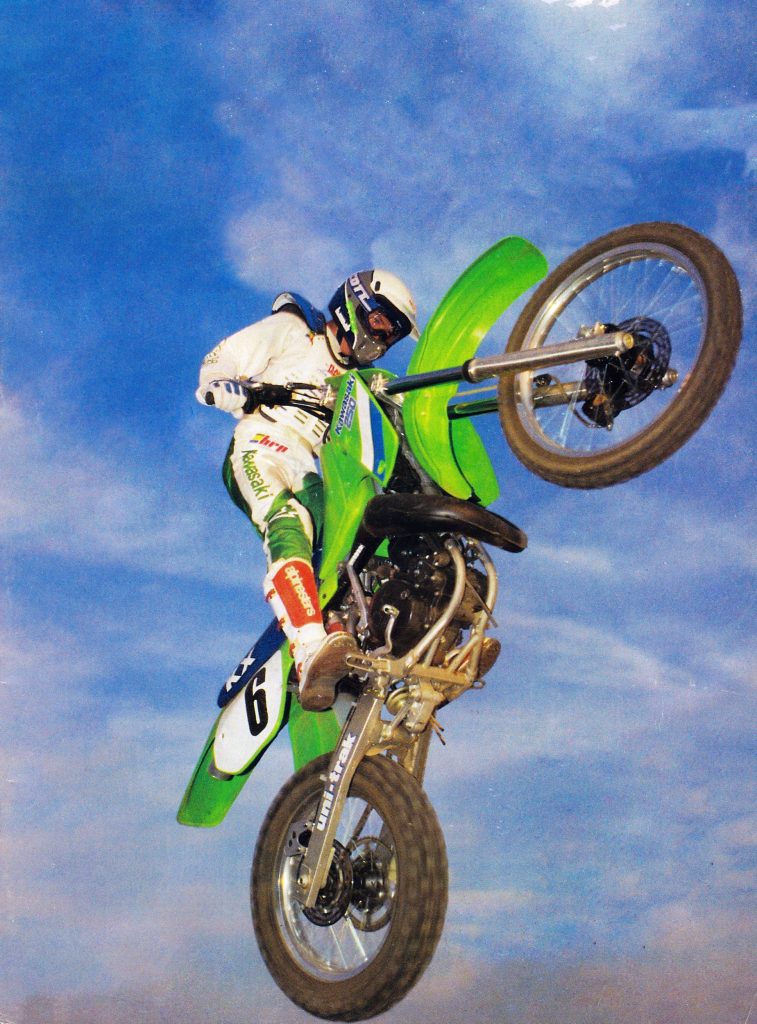

Factory Kawasaki’s Ronnie Lechien piloted the all-new KX250 to a pair of third overalls in the 1987 Supercross and 250 National Motocross standings. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1986, the CR’s closest competitor had been Kawasaki’s KX250. The green deuce-and-a-half offered a brawny low-end hit that riders loved, but it lacked the suspension and handling finesse of the class-leading Honda. It’s non-cartridge KYB forks were not even in the same performance zip-code as the Honda’s excellent Showa cartridge dampers and its chassis felt vague and sluggish compared to the razor-sharp red machine. For 1987, Kawasaki looked to unseat Honda by building on the strengths of the ’86 design, while addressing the problems that had kept them out of the winner’s circle the year before.

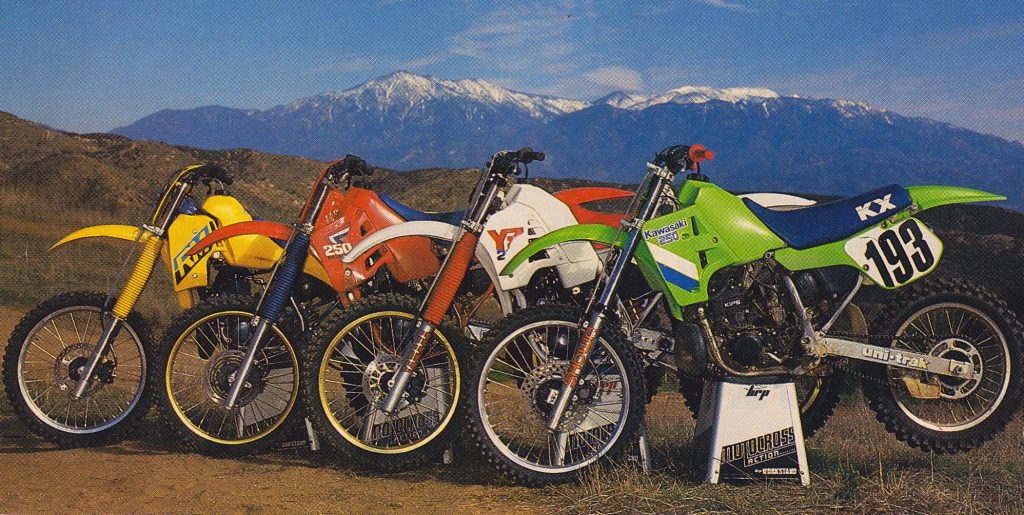

Three of the four machines in the 250 class were all-new for 1987. Only the YZ250 (redesigned in 1986) was a carryover from the year before. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

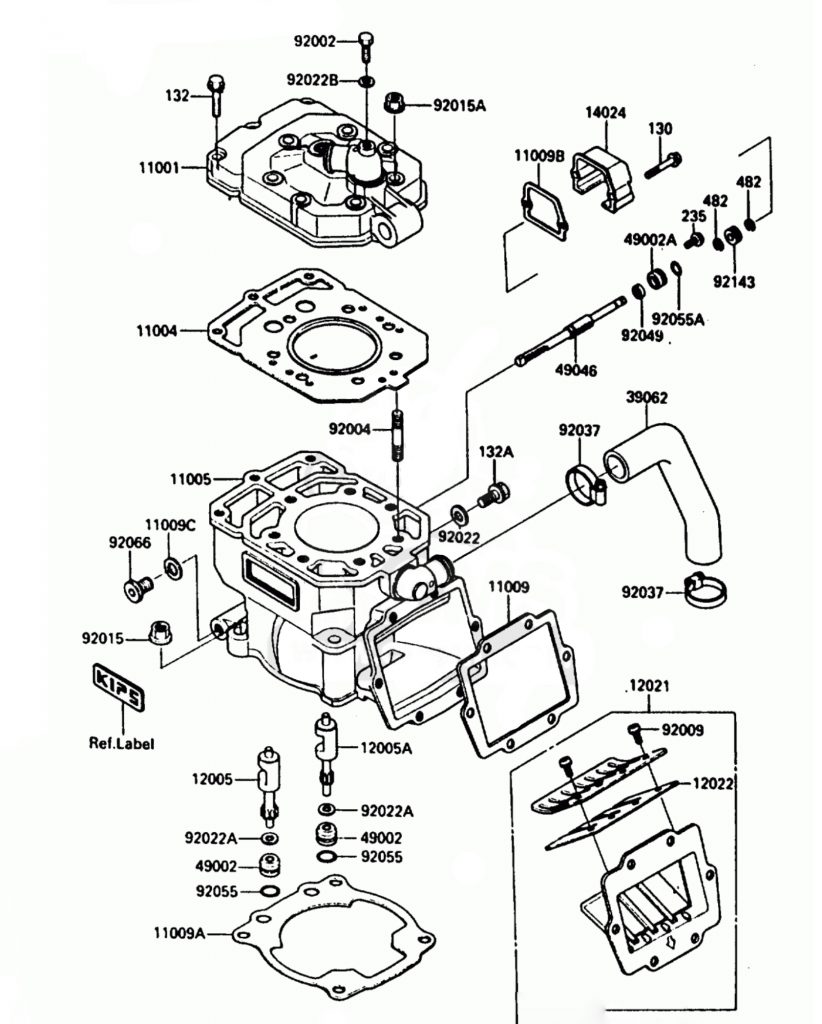

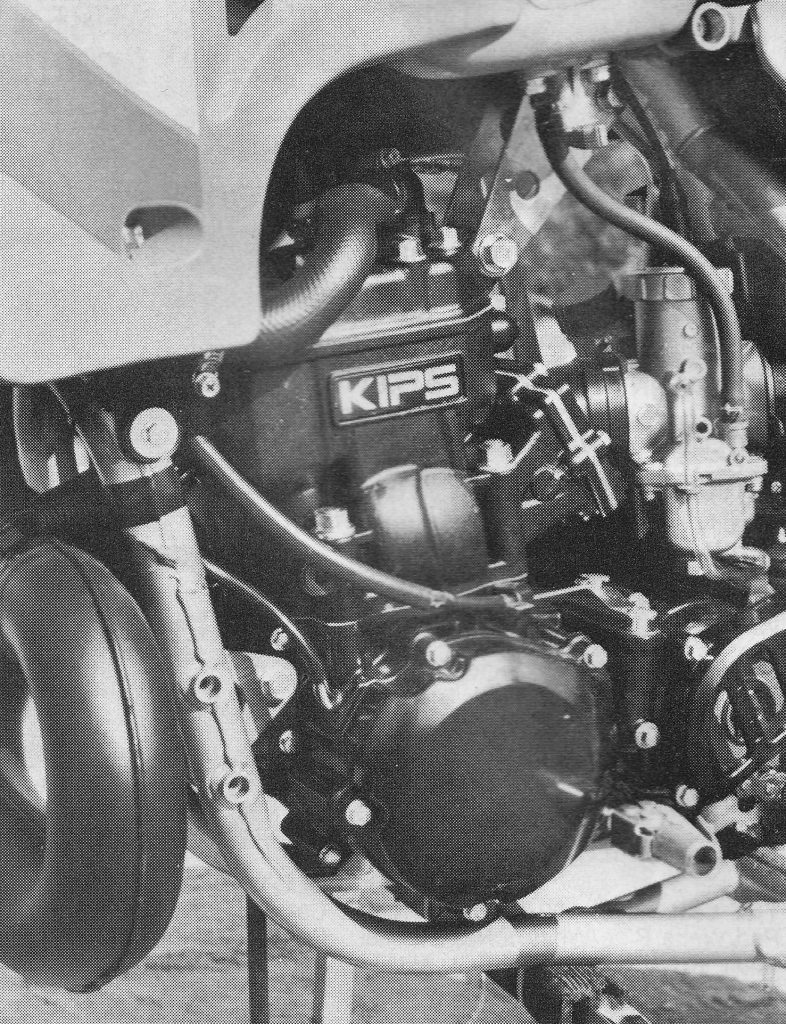

Chief among these strengths was the KX’s excellent power plant. In 1986, the Kawasaki’s 249cc mill was the most advanced design in motocross. Its KIPS (Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System) power valve design incorporated both the variable exhaust port of the Yamaha YVPS (Yamaha Power Valve System) and the exhaust resonance chamber of the Honda ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) to provide one of the strongest power packages of ’86. The KX was not as long-pulling as the CR, but it provided a chunky blast of power that was both fun and fast.

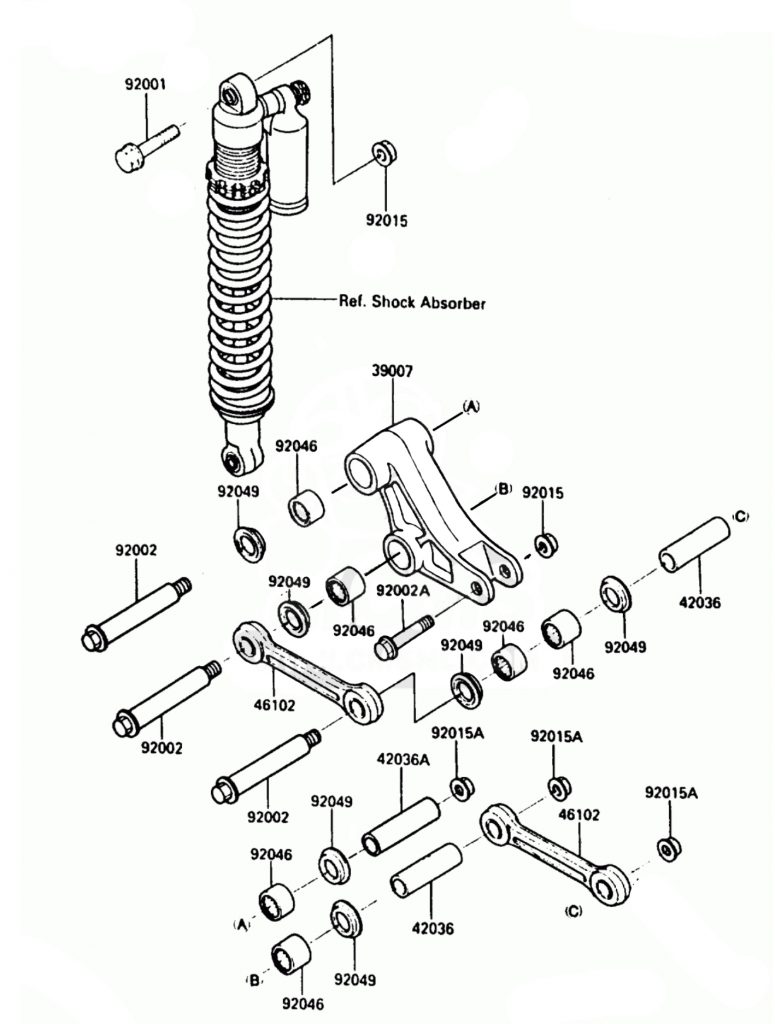

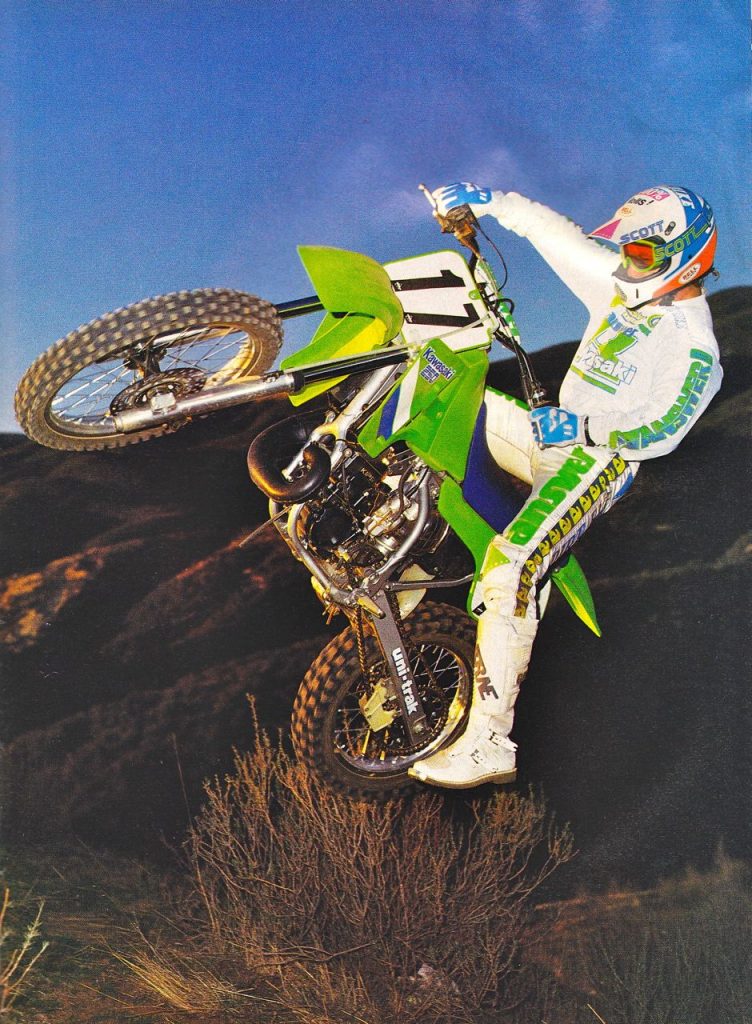

The most dramatic change on the KX250 for 1987 was the adoption of an all-new “bottom-link” Uni-Trak rear suspension. The new configuration did away with the iconic “dog-bone” link Kawasaki had employed since 1980 and replaced it with an arrangement very similar to Honda’s Pro-Link design. This lowered the center of gravity and allowed Kawasaki to move the shock forward for improved mass centralization. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1987, Kawasaki looked to build on this success by making several significant changes to its well-regarded power plant. First up was a reconfiguring of the bore and stroke for ‘87. The new motor maintained the same 249cc displacement, but reduced the bore by 2.6mm and increased the stroke by 5.1mm. This new 67.4mm x 70mm configuration was designed to boost the tractability and torque of the KX’s already excellent low-to-mid powerband.

Major engine updates for 1987 included a longer stroke and smaller bore for the 249cc motor. Revisions to the KIPS included a switch from steel to aluminum for the power valves and larger openings for improved exhaust flow. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1987, Kawasaki also wanted to get their tractor of a motor to pull farther on top, so they redesigned the KIPS slightly to provide better breathing and quicker response. Both the KIPS valves and the associated ports were enlarged for 1987 and the material of the valves was changed from steel to aluminum to reduce weight. The gears activating the KIPS mechanism were also lightened for ’87. New porting was added to match the redesigned motor configuration and an all-new head was paired with a reshaped dome-top piston to boost compression to 10.6:1.

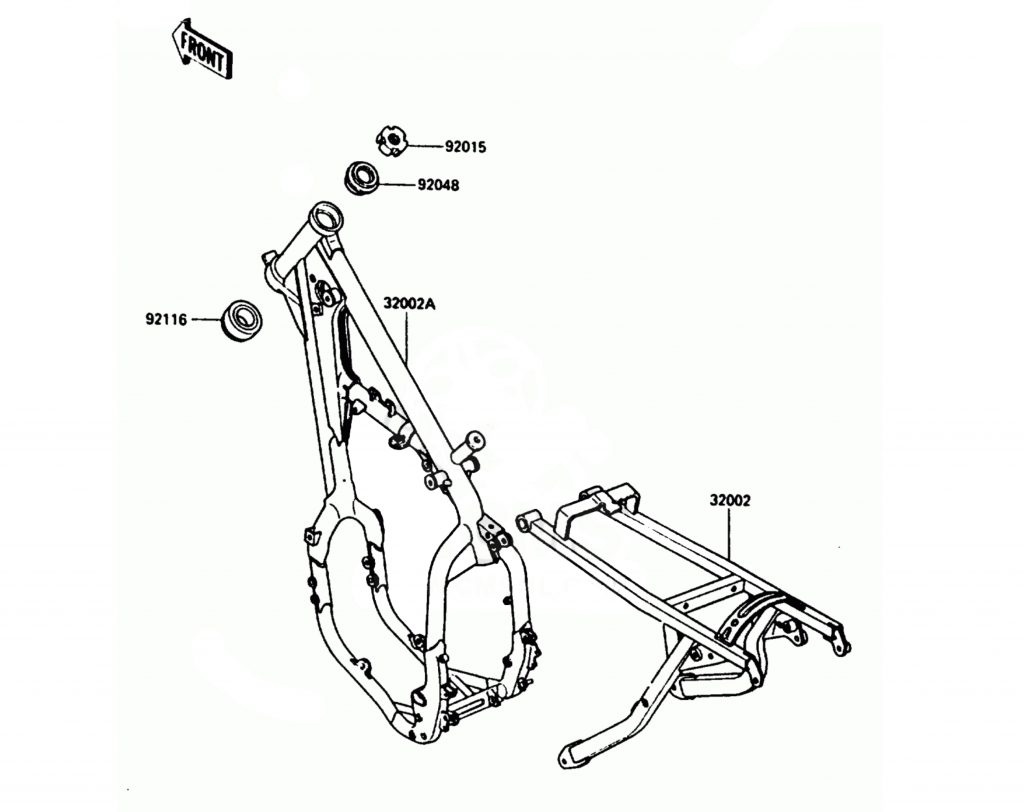

An all-new frame for 1987 added a fully-removable rear sub-frame to the KX250 for the first time. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Feeding fuel to the motor was an eight-pedal carbon fiber reed-valve and an all-new 38mm “R-bottom” Mikuni carburetor. This new mixer replaced the massive 40mm unit of 1986 and was said to offer improved intake velocity for quicker response. Mounted to the carburetor was an all-new airbox which featured a free-breathing design Kawasaki coined the “Fresh Air Induction System” (FAIS). This new FAIS airbox drew air from under the gas tank and was said to improve airflow and reduce servicing by bringing cleaner air into the motor. Complementing the new intake system was a redesigned exhaust and lightweight alloy silencer that helped get all of those spent gasses out of the motor as efficiently as possible.

Anorexic: The KX250’s all-new bodywork offered the slimmest seat-tank junction in the class in 1987.

On the bottom end, the new KX featured the same five-speed gearbox as 1986 but new ratios were added to work more effectively with the new power profile. In addition to the new gear sets, a redesigned clutch was added that looked to upgrade the 1986’s lackluster action. To do that, Kawasaki swapped the steel drive plates of ’86 for lighter aluminum units and reduced the thickness of the friction plates. This was done to lighten the clutch and help make the motor feel more responsive. To fight the fading issues of ’86, the new clutch added an additional spring, raising the total of coils to six. To improve the feel at the lever, Kawasaki added a bushing to the actuation push rod and needle bearings to the clutch release shaft.

Long and strong: The ’87 KX250’s new long-stroke motor offered an instant response and a chunky delivery. It romped from the first crack of the throttle and outpowered everything else in the class through the midrange. Top-end power was nonexistent, but as long as you did not try to over rev, it was more than capable of winning at any level. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the chassis side, Kawasaki dialed up an all-new frame for 1987. In 1986, the KX125 had retired the original “dog bone” Uni-Trak linkage in favor of a new “bottom-link” design very similar to Honda’s Pro-Link. This new design kept the Uni-Trak name but offered a much more compact layout and significantly improved weight distribution. With the new bottom-link layout, the weight of the linkage was both reduced and placed far lower on the chassis. The shock was also mounted lower on the frame and moved forward slightly to better centralize mass.

In 1987, the 250 class served up a varied selection of slightly flawed offerings. The Suzuki ruled the suspension categories but its motor lacked the boost of the best machines in the class. The Yamaha looked great but featured a narrow powerband and utterly grim suspension. The Kawasaki offered a super-fun and snappy motor but offset it with outdated forks that knocked it down a notch in the final standings. Despite a thoroughly mediocre shock, it was the Honda that took home the crown by offering brilliant forks, excellent ergos, sweet looks, and a Saturn V rocket booster of an engine. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For 1987, the KX250 got this upgrade and an all-new frame to accommodate it. The frame remained a traditional chromoly steel unit with a single backbone and a large single downtube that split into an engine cradle at the exhaust port. New for 1987 was a fully removable rear subframe that made servicing the new shock much easier. Overall steering geometry remained unchanged from 1986, but the new chassis offered a much different weight distribution than the year before.

With its instant throttle response and powerful low-to-mid hit, care had to be taken not to get a little more boost than you bargained for on the ’87 KX. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

For the redesigned Uni-Trak, Kawasaki did away with literally every component from the 1986 KX250 rear suspension system. The new design relocated the linkage to below the shock and incorporated an all-new Kayaba damper. The new shock ditched the remote reservoir of ’86 in favor of a new, more efficient “piggyback” design and offered a hard-adonized shaft for longevity and 16 adjustments for compression and rebound. Overall travel increased as well, moving up .4-inches to a full 13-inches for 1987.

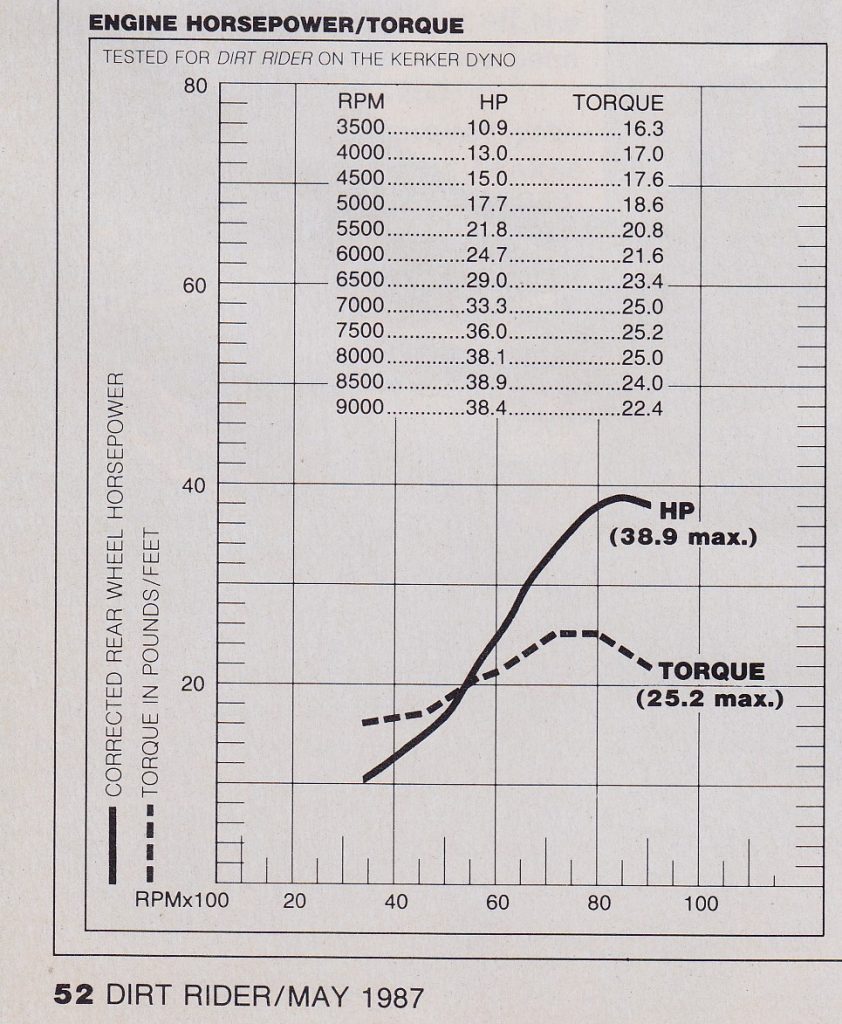

Today, 38.9 horsepower does not sound like a lot (a modern 250F dwarfs this figure) but in 1987 that put you at the top of the 250 standings. That was nearly four horsepower more than the ‘87 RM250 and surprisingly even more than Honda’s blisteringly fast CR250R. On the track, the Honda felt faster, but in the lab, the two motors were far closer than one might have expected. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Up front, Kawasaki missed the boat a bit in 1987 by only offering an updated version of the 43mm non-cartridge Kayaba forks it had used in 1986. The year before they had been soundly trounced by Honda’s new Showa’s cartridge design and for 1987, that competition had only gotten steeper with the introduction of Suzuki’s cartridge fork system. With Honda and Suzuki both offering these sophisticated works-style damping systems, Yamaha and Kawasaki were at a distinct disadvantage in the 1987 fork wars.

With its explosive low-end burst the KX made short work of berms in 1987. Here factory Kawasaki’s Eddie Warren demonstrates with Motocross Action’s test bike. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For 1987, Kawasaki did try to improve their fork’s mediocre performance by massaging their position-sensitive Travel Control Valve (TCV) damping system to provide smoother operation. Internally, there was a new compression spring and revised damping settings to go with a new “floating” pushrod that was claimed to offer a plusher feel. Overall travel remained unchanged at 11.8-inches with the new fork offering 16 adjustments for compression but no external adjustments for the rebound.

The KX250 was a good-looking machine in 1987. Photo Credit: AXO Sport USA

In addition to a redesigned chassis, the new KX250 offered completely new bodywork that freshened up its looks and offered much-improved ergonomics. An all-new tank reduced capacity by half a gallon but made up for it by offering the slimmest seat-tank junction in the class. The new seat and tank were so thin that some riders complained that it was hard to grip the bike with their knees until they became accustomed to it. The slim layout did make it easier to move around and slide forward in the turns and gave the bike a nimbler feel than before. Most riders loved the new super-slim layout but off-roaders lamented the reduced range the smaller tank provided.

The all-new KX250 proved its worth in 1987 by taking Jeff Ward to his second AMA Supercross title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

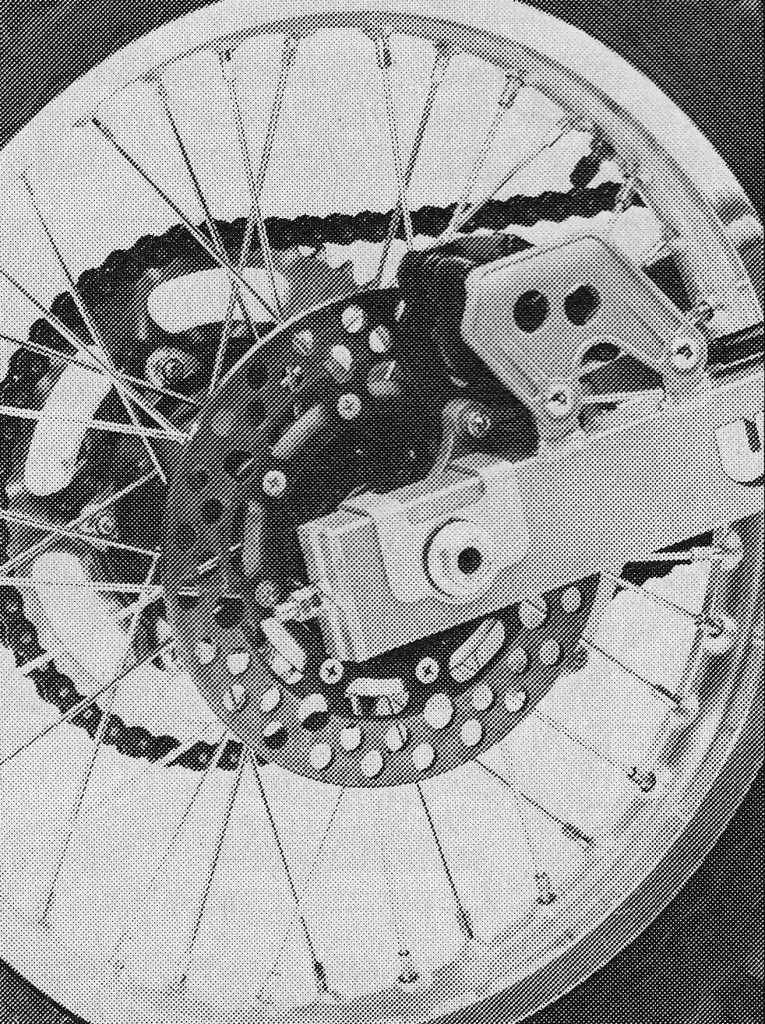

Finishing off the significant changes for 1987 was an all-new front master cylinder and caliper for the KX’s disc braking system. The new caliper retained its single-piston layout but featured a new 12% larger piston and 25% larger pads. Kawasaki claimed this added up to a 20% increase in pucker power over 1986. In addition to being more powerful, the new brake offered improved feel through a change in pad material and the addition of a 20mm shorter lever. In the rear, the brake remained largely unchanged, but a new pad material looked to reduce the “grabbiness” many riders had complained about in 1986.

Potent Pucker Power: In the early 1990s, Kawasaki struggled with mushy and underpowered brakes, but in 1987 that was not an issue. The KX’s dual-disc binders were the most powerful stoppers in motocross. Compared to the Honda’s discs they were slightly grabby and more difficult to modulate but no one went back to the truck asking for more power in 1987. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the track, the new KX turned out to be one of the most fun machines to ride in 1987. Its new long-stroke motor produced the kind of churning low-end rush usually reserved for Open bikes. It jumped from the first crack of the throttle and rocketed though a blistering midrange blast. Just as in 1986, there was not much on tap above this midrange surge, but the engine was more than capable of pulling the KX to the front against its rivals. Compared to the class-leading Honda it was far softer on top, about equal through the middle and significantly better down low. What the Honda accomplished with revs, the Kawasaki did with gobs of tractor-like torque. Both were equally effective on the track, but they required very different riding techniques to make the most of their performance. On the KX, it was best to ride it like an Open bike; keeping it a gear high and using its strong torque to pull you from turn to turn. As long as you did not try to scream it, it was fun, fast, and brutally effective.

By far the biggest crack in the ’87 KX250’s armor was its 43mm conventional KYB forks. Compared to the excellent Honda and Suzuki cartridge units these old-fashioned Travel Control Valve forks were under-sprung, harsh, and prone to valving spikes. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While most riders loved its meaty vibes, some inexperienced pilots found its ultra-responsive power slightly intimidating. There was no waiting for the power to build and the slightest twist of the throttle resulted in the bike rocketing forward. This made the KX slightly tricky out of corners and off jumps if you were imprudent with the go handle. Again, riding it like a big bore and keeping it a gear high was the best way to get the bike hooked up and prevent any unexpected sidesteps by the rear end. This strategy also helped take the pressure off of the KX’s mediocre clutch and slightly notchy transmission. Both of these units were improved for 1987, but neither offered the durability and feel of Honda’s excellent and bullet-proof units.

The new Uni-Trak rear suspension on the KX proved far more effective than its disappointing forks. Overall, it was rated the second-best rear end of 1987. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While the KX’s engine performance was praised by most, the same could not be said of its 43mm KYB forks. In stock condition they were harsh in action and prone to damping spikes in the mid-stroke as the conventional dampers struggled to flow oil fast enough to avoid a momentary hydraulic lock. This was where the new cartridge forks excelled and the old-style forks on the Kawasaki and Yamaha really suffered by comparison. The KX’s forks were not as woefully bad as the ones found on the Yamaha, which appeared to have been set up for the moon, but they were not even remotely in the same class as the excellent units found on the Honda and Suzuki. With stiffer springs and a switch to 5-weight oil they were at least raceable, something that could not be said of the YZ’s grim reapers. If you had the cash, the real fix was Kawasaki’s cartridge accessory kit which replaced all of the fork’s internals and drastically improved performance. At a cool $300 ($700 in today’s money), it was not cheap but for fast guys it was a worthwhile investment.

Never renowned for its handling prowess, the KX250 made significant strides in 1987. The new bike was decently stable and turned better than in the past, but it continued to lack the steering precision of the Honda. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Out back, the situation was better with Kawasaki’s new Uni-Trak system. The new shock performed very well in most situations with the only complaint being a “dead” feeling in some conditions due to its heavy rebound damping and a slight spike in the mid-stroke. No one called it plush, but it was well-controlled and perfectly raceable in stock condition. The new shock’s reliability was also improved with a hard-coated shaft and rebuildable internals. Overall, the KX’s shock was rated far above the confused Honda and jackhammer Yamaha, but well below the ultra-plush Suzuki.

With a swap to KX500 springs and an upgrade to Kawasaki’s accessory cartridge fork kit the KX250 became a true threat to claim the title of best 250 of 1987. Here Dirt Rider’s Terry Swanson demonstrates. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

On the handling front, the KX remained a middle-of-the-road performer. The new layout made it easier to get forward in the turns but the frame’s relatively sedate geometry and long feel prevented the KX from offering the same sort of steering precision enjoyed by the CR250R. In turns, it preferred to bank off of berms rather than cut to the inside. It was better than previous KXs on flat ground and the front end felt decently planted as long as quality rubber was installed. At speed, the KX was reasonably stable and split the middle between the slightly schizoid Honda and rock-solid Yamaha. In the rough, the bikes steering precision and stability suffered, but that was more a factor of its sub-par forks than any inherent problem with its chassis.

With the advent of the Production Rule the year before, Jeff Ward’s ‘87 SR250 had to share far more with the production KX than his 1985 championship machine ever had. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the detailing department the KX was improved for 1987 but not without its faults. The new brakes were super powerful and a noticeable increase in performance over 1986. Fast guys loved the ability to stop on a dime but care had to be taken not to stall the motor with the rear’s sudden engagement. Clutch action was smoother at the lever but it was still not a fan of any major abuse. While the motor ran well, fouled plugs seemed to be a common problem, and rejetting did not seem to completely exorcise this annoying occurrence. The removable rear subframe made servicing the shock easier than ever and the new FAIS airbox seemed to keep the air filter clean longer than the competition. The new rims proved far less brittle than in the past, but the rest of the KX’s assorted nuts and bolts were the same pot-metal garbage Kawasaki had been sticking on their machines since the Sixties. Speaking of brittle, the KX’s new plastic proved by far the least durable in the class. Just squeezing the shrouds too hard on a cold day was often enough to crack their fragile structure and cinching down a gas cap too snugly was a surefire way to douse your nuts with gas as the cap split and puked 92 octane in your lap. As with nearly all machines of its time, the stock bars, grips, sprockets, and chain were all garbage, but this was expected in 1987. Lastly, the new shock’s internals laster longer, but bent shafts were a common occurance on KX’s ridden by pros. Riders of average skill were less likely to suffer this malady but it was worth mentioning if you were planning on trying to keep up with the triple-hucking set.

In 1987, Kawasaki introduced by far their most-competitive quarter-liter machine to date. Fast, fun, and ultra-competitive, the redesigned KX250 offered a stark alternative to the Honda’s pro-oriented mid-and-up power profile. For those looking to roost rather than rev, the torquey KX was tons of fun and a rock-solid choice in 1987. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Overall, the 1987 Kawasaki KX250 turned out to be by far the most-competitive 250 machine ever offered by the green team. It offered the slimmest layout, most powerful brakes, and most torque in the class. It was not as blazing fast on top as the Honda, but it was far easier to ride than the demanding red machine. Most of all, it was fun, with its barky low-end blast and razor-thin feel. If only it had been blessed with a decent set of forks, it would have been the king of the ’87 250 class, but as it was, it was a set of silverware away from greatness.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com