For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Yamaha’s all-new YZ125 for 1989.

All-new from the ground up, the 1989 Yamaha YZ125 certainly looked the part with its sexy YZM-inspired styling. Photo Credit: Yamaha

All-new from the ground up, the 1989 Yamaha YZ125 certainly looked the part with its sexy YZM-inspired styling. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The eighties were a very up and down decade for Yamaha’s venerable YZ125. After starting off the decade with some strong performers, the YZ went into the doghouse with a run of woeful 125s. In stock condition they were painfully slow, and once modified, they were painfully slow and unreliable. In 1984 and 1985, the YZ125 became the notorious punching bag of magazine editors looking for colorful canine metaphors to describe its pokey performance.

In 1986, Yamaha introduced an all-new motor that finally pulled the YZ out of the 125 doghouse. This case-reed mill gave the mid-eighties YZ125s tons of burst but not much rev. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1986, Yamaha introduced an all-new motor that finally pulled the YZ out of the 125 doghouse. This case-reed mill gave the mid-eighties YZ125s tons of burst but not much rev. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1986, Yamaha finally broke out of this slump by introducing a completely redesigned YZ125. The new YZ’s case-reed engine was punchy, potent, and worlds faster than the lethargic ’85 had been. The ’86 Why-Zed was sleeker, slimmer, and far more competitive than anything Yamaha had offered in the 125 class in half a decade. With its cranky clutch and notchy shifting it was not up to unseating Honda’s omnipotent CR125R at the top, but it did finally bring Yamaha back from irrelevance in the 125 class.

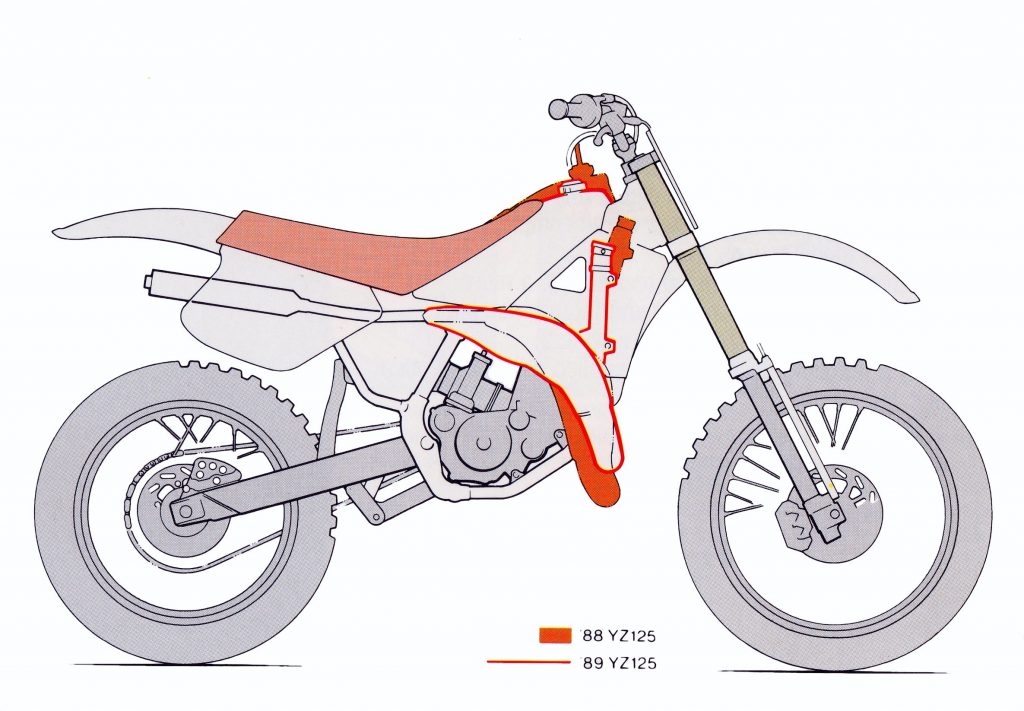

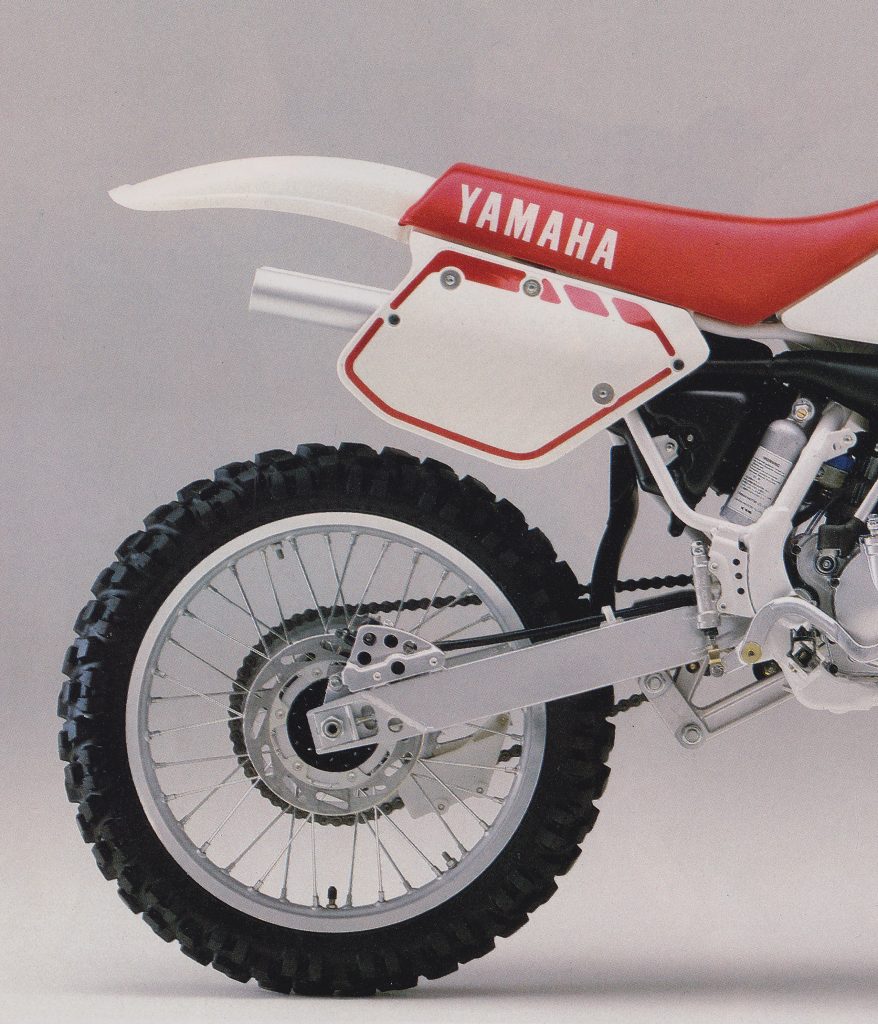

An all-new chassis and bodywork highlighted the redesigned YZ125 package for 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new chassis and bodywork highlighted the redesigned YZ125 package for 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

After once again losing out to Honda’s red ripper in 1987 and 1988, Yamaha set about a plan to reclaim the title of best 125 in the land for 1989. To do this, the engineers dialed up an all-new design that looked to improve the handling, ergonomics, and power of their eighth-liter racer. This reimagined machine did away with 90% of the 1988 design and featured an all-new chassis, re-engineered suspension, and completely new bodywork. Even the motor, which was all-new in 1986, was reworked and massaged to boost rideability and overall performance.

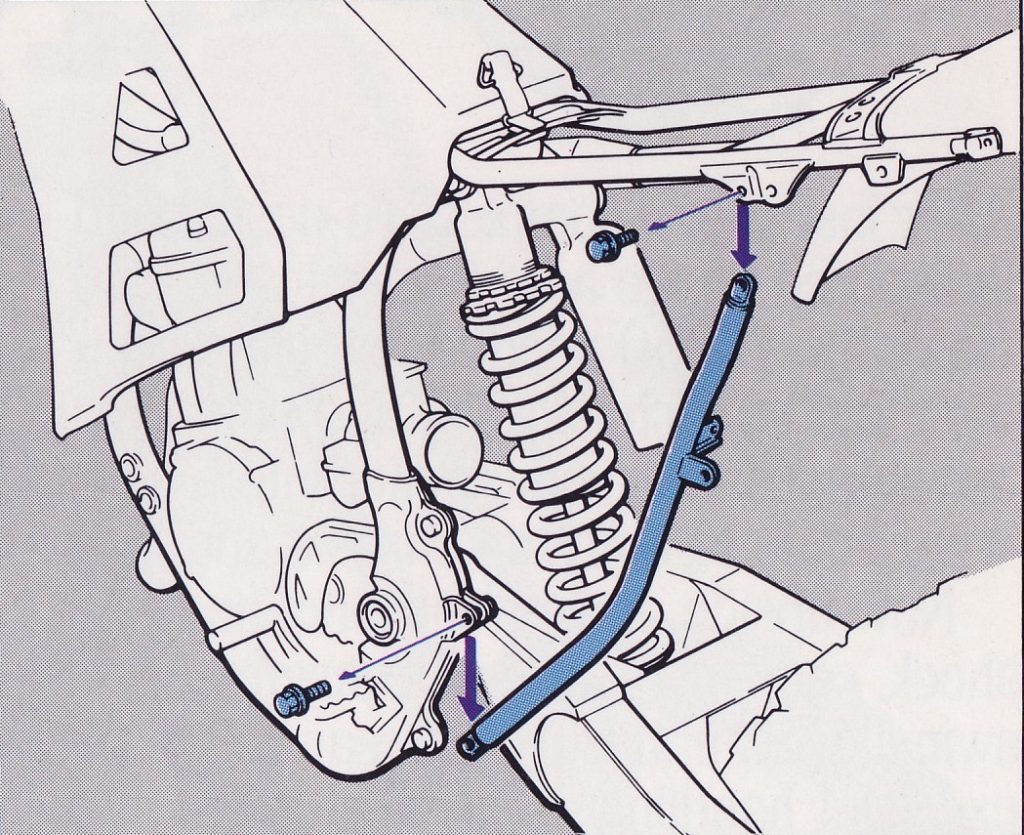

For 1989, Yamaha’s engineers finally added a removable spar to the rear of the frame to aid shock access. Photo Credit: Yamaha

For 1989, Yamaha’s engineers finally added a removable spar to the rear of the frame to aid shock access. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1988, the YZ125 had been a decent middle-of-the-road handler that lacked the precision of the Honda and the planted feel of the Kawasaki. It was front-end light coming out of turns and there was a generally unsettled feel to the chassis. Much of this was due to the YZ’s shock which was busy in the rough and prone to kicking when not under power. The ’88 YZ125’s handling was not a total disaster but it did lack the finesse of some of its rivals.

The new bodywork for 1989 increased fuel capacity by half a liter and centralized mass by flattening the tank, lowering the radiators, and repositioning the exhaust. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The new bodywork for 1989 increased fuel capacity by half a liter and centralized mass by flattening the tank, lowering the radiators, and repositioning the exhaust. Photo Credit: Yamaha

For 1989, Yamaha looked to rectify this by dialing up an all-new frame for the YZ125. The new frame was stronger for ’89, featuring beefed-up square tubing for the main downtube and a massive increase in bracing around the swingarm pivot. Overall geometry was altered slightly with a 5mm increase in the trail and a slight reduction in rake. The new frame also finally added a removable section to the rear to aid shock servicing. This removable spar was not as convenient as the fully removable subframe found on the Hondas, but it was a significant improvement over the previous Yamaha designs.

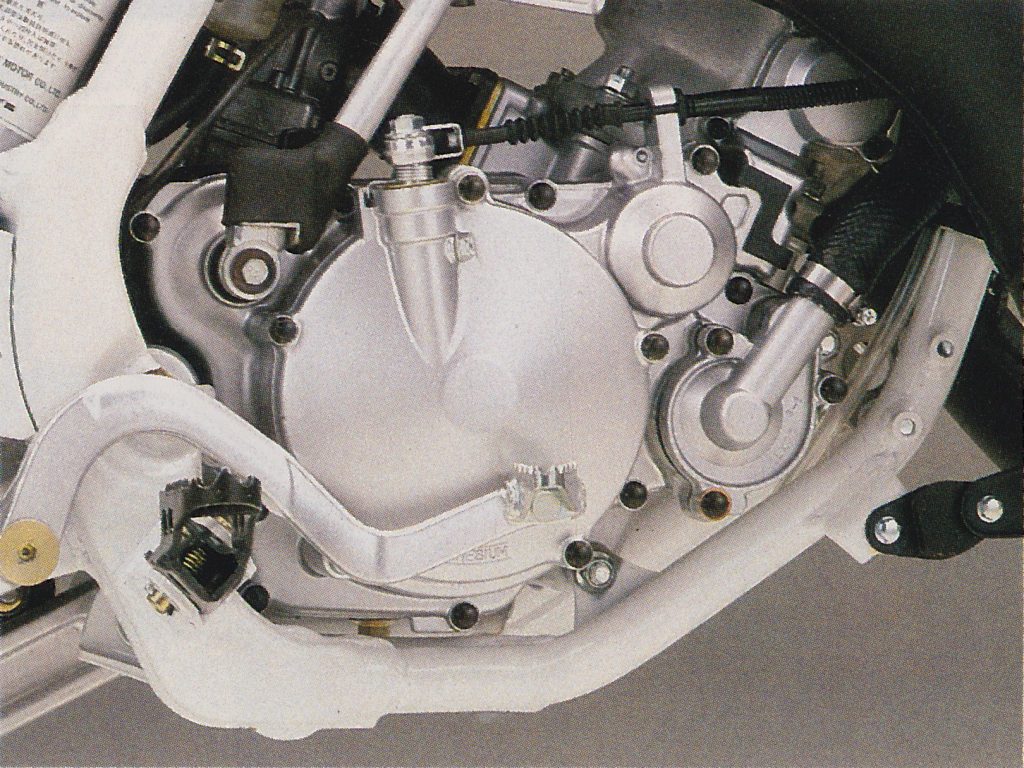

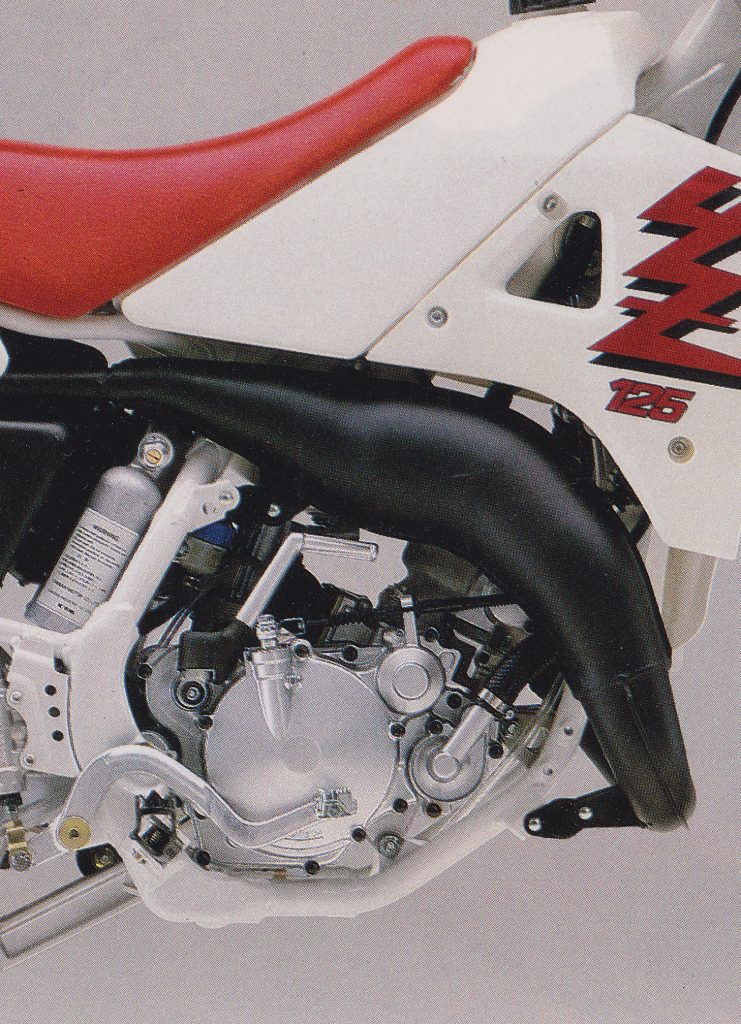

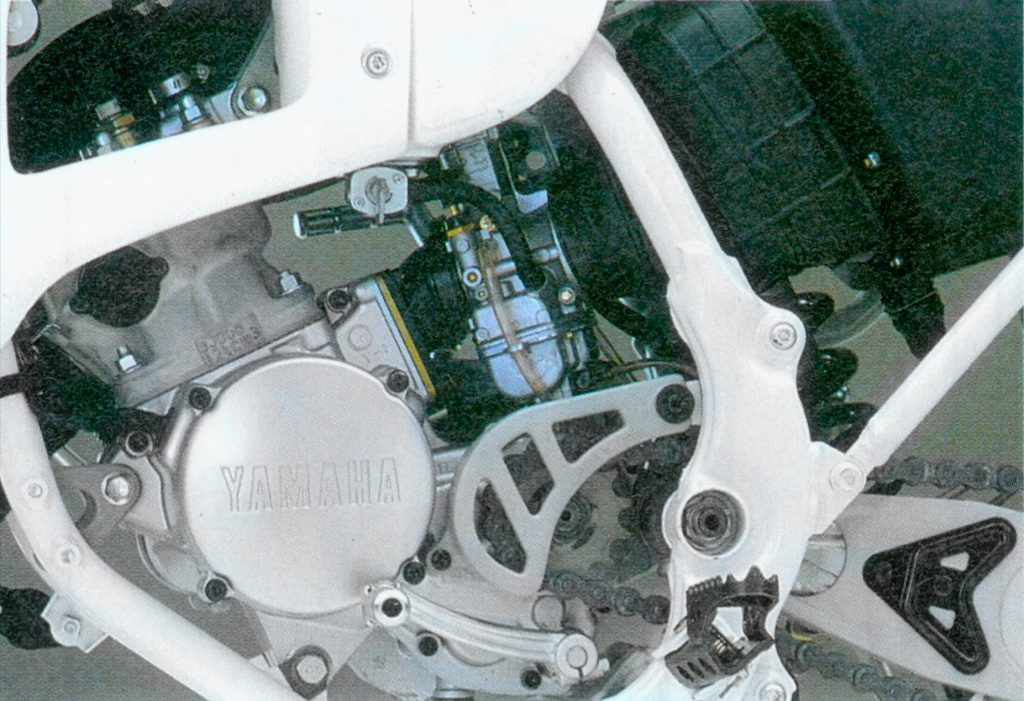

A new two-piece clutch cover aided servicing in 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

A new two-piece clutch cover aided servicing in 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Adding to the sturdier feel for 1989 was all-new suspension both front and rear. Up front, Yamaha spec’d an all-new set of 41mm Kayaba inverted forks that promised increased rigidity, more precise action, and a decrease in rut-catching underhang below the axle. The new inverted design provided a more precise feel by moving the larger diameter fork tubing to the upper clamp area, increasing the slider overlap by 30%, and introducing a new tapered shim stack in the cartridge system. The new forks offered 11.8 inches of travel and an external adjustment for compression damping but it did lack the rebound adjustability found on some of its rivals.

In 1989, Yamaha became the first Japanese manufacturer to bring an inverted fork to the 125 class (KTM had beat all the Japanese to this way back in 1985). The new 41mm inverted Kayaba cartridge units offered increased rigidity and greater clearance below the axle compared to the conventional fork designs of the time. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1989, Yamaha became the first Japanese manufacturer to bring an inverted fork to the 125 class (KTM had beat all the Japanese to this way back in 1985). The new 41mm inverted Kayaba cartridge units offered increased rigidity and greater clearance below the axle compared to the conventional fork designs of the time. Photo Credit: Yamaha

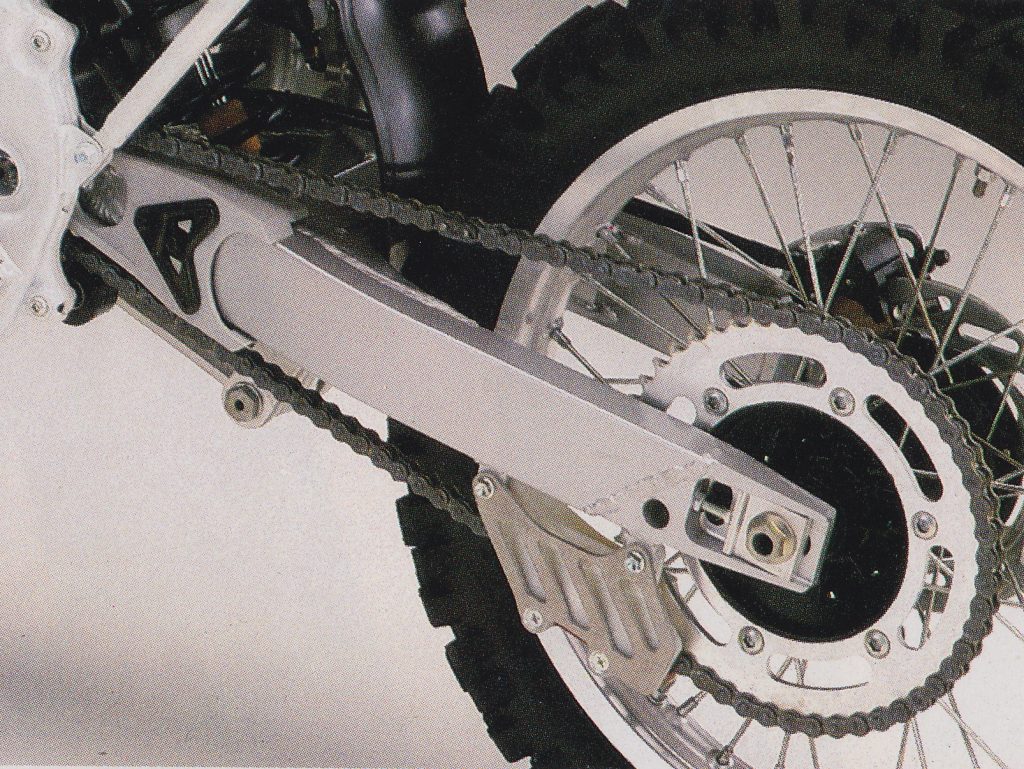

In the rear, the ’89 YZ125 featured an all-new Monocross rear suspension system. The redesigned swingarm was larger overall and significantly stronger than in 1988. In addition to being more resistant to flex, the new swingarm improved maintenance and reliability by switching to “push-style” chain adjusters and adding significant bracing to the chain guide. The chain buffer was also redesigned to be softer and much quieter than the rock hard and annoyingly loud unit employed in 1988.

An all-new swingarm was larger and stronger for 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new swingarm was larger and stronger for 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

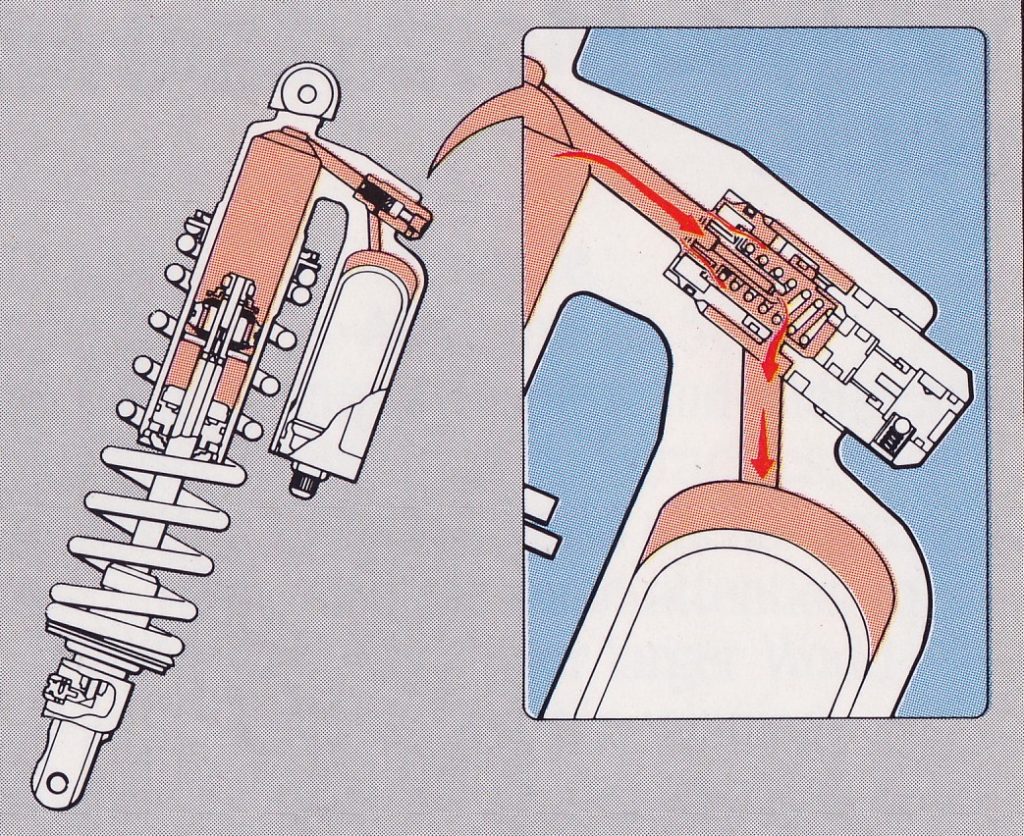

Mated to the redesigned swingarm was an all-new rising-rate linkage that was engineered to provide a more progressive action for 1989. An all-new Kayaba shock was also spec’d that was lighter and more durable with hard-anodized components and a switch from steel to aluminum for the shock’s body. Internally, the new damper featured tighter tolerances and a redesigned valving system that promised to provide smoother action by reducing stiction. Overall travel was set at 12.3 inches with external adjustments available for both compression and rebound damping.

An all-new Kayaba shock was paired with the redesigned Monocross linkage for 1989. The new shock was lighter and featured a redesigned valving system for improved action. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new Kayaba shock was paired with the redesigned Monocross linkage for 1989. The new shock was lighter and featured a redesigned valving system for improved action. Photo Credit: Yamaha

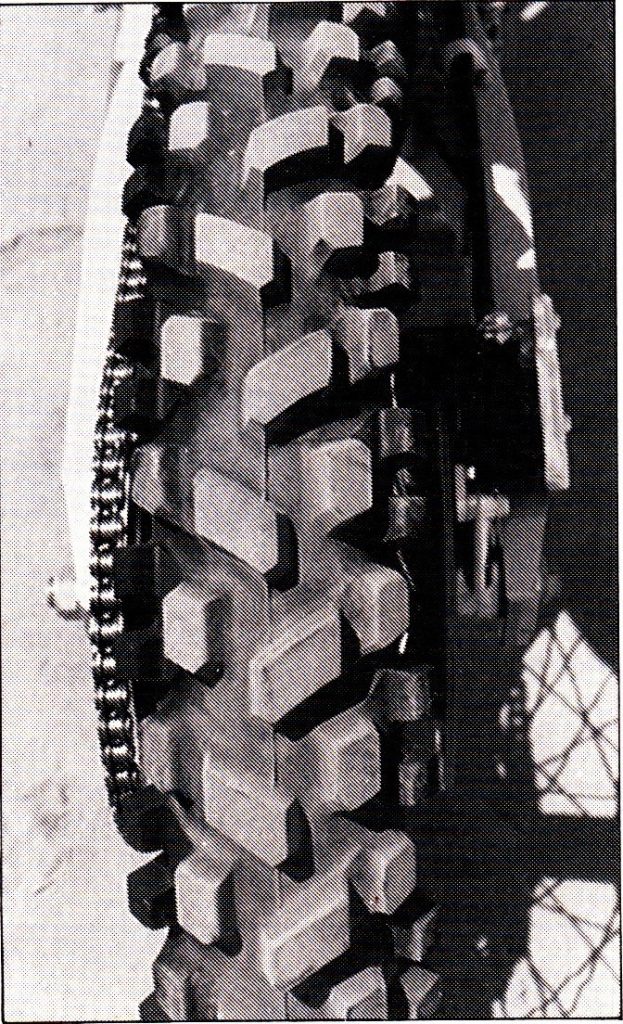

In addition to the redesigned rear suspension, the 1989 YZ125 featured an all-new “works style” 19-inch rear wheel that was designed to improve straight-line acceleration and provide a more precise cornering feel. In use for several years by the factory race teams, the 19-inch hoop allowed for the use of a lower profile tire, which was preferred for its reduced flex characteristics under heavy loads. In addition to the new rear wheel, both braking systems were upgraded with new rotors, redesigned calipers, revised pad compounds, and a change in the front leverage ratio. All these changes added up to a claimed 20% increase in braking performance for 1989.

In 1989, Yamaha switched to a 19” rear wheel on the YZ125. This limited tire selection somewhat initially but the new larger hoop offered a more precise feel under heavy cornering loads. This somewhat unique Bridgestone “Tractor” tire came stock on the YZ125 but not YZ250 in 1989. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1989, Yamaha switched to a 19” rear wheel on the YZ125. This limited tire selection somewhat initially but the new larger hoop offered a more precise feel under heavy cornering loads. This somewhat unique Bridgestone “Tractor” tire came stock on the YZ125 but not YZ250 in 1989. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Finishing off the chassis changes for ’89 were all-new plastic components that closely mimicked the YZM–style bodywork introduced on the YZ250 in 1988. This redesigned plastic freshened the YZ’s looks and improved the riding compartment significantly. The new seat featured a flatter profile that carried all the way up to the gas cap; matched to the seat was a redesigned fuel cell that featured slightly more capacity (by 0.13 gallons) and a significantly lower profile to aid rider movement. Both the tank (25mm) and radiators (40mm) were relocated to sit lower down on the chassis to further improve handling. Bolted to the tank were all-new asymmetrical shrouds that helped give the YZ a bit of the YZM’s exotic “works bike” look. In addition to being lower, the new radiators offered an increase in capacity for 1989. Cosmetically, both the side plates were redesigned to be smaller and more stylish for ‘89, with the left side losing the ’88 model’s side-access airbox cover.

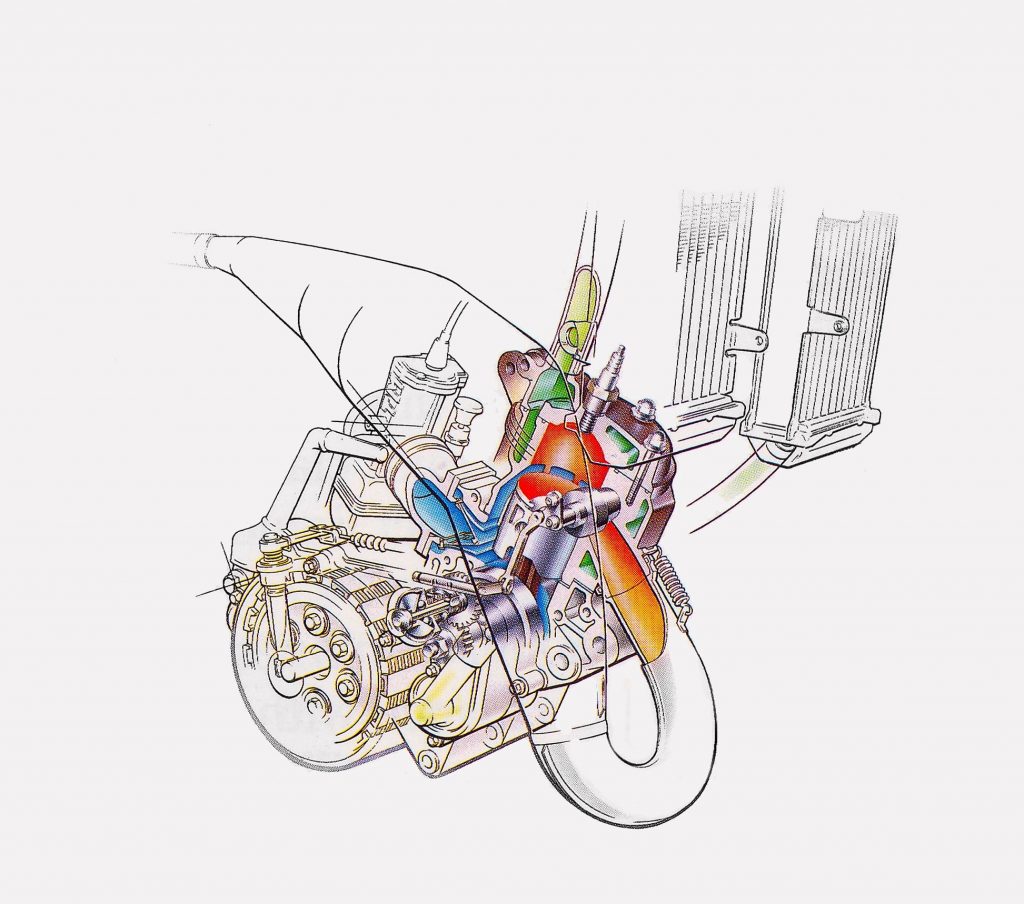

A longer stroke, new cylinder, revised YPVS and massaged transmission highlighted the motor changes on the YZ125 for 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

A longer stroke, new cylinder, revised YPVS and massaged transmission highlighted the motor changes on the YZ125 for 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the motor side, Yamaha dialed up a significant amount of changes for 1989. Externally, the engine looked largely unchanged, but internally, Yamaha made some major moves aimed at broadening the YZ’s punchy but short delivery. The first among these changes was a new crank that increased the motor’s stroke by 0.7mm. This change added up to a 1.8cc increase in displacement for 1989. The shape of the lower cases and intake were also modified to provide better flow and faster crankcase stuffing. Mated to the new bottom end was a redesigned cylinder that maintained the old-style Yamaha Power Valve System but added all-new porting and a reshaped drum for the YPVS. For 1989, the cylinder also ditched the heavy steel liner of previous YZs in favor of a new Nikasil coating that was tougher, lighter, and better at shedding heat. While ultra-tough, this move to Nikasil did mean that boring the cylinder in the event of a catastrophic failure would no longer be an option. Finally, finishing off the new top-end was a redesigned piston, which featured increased compression and a reduction in distance of 2mm between the crown and wrist pin to increase strength. To further improve durability, four holes were drilled into the piston skirt to increase lubrication.

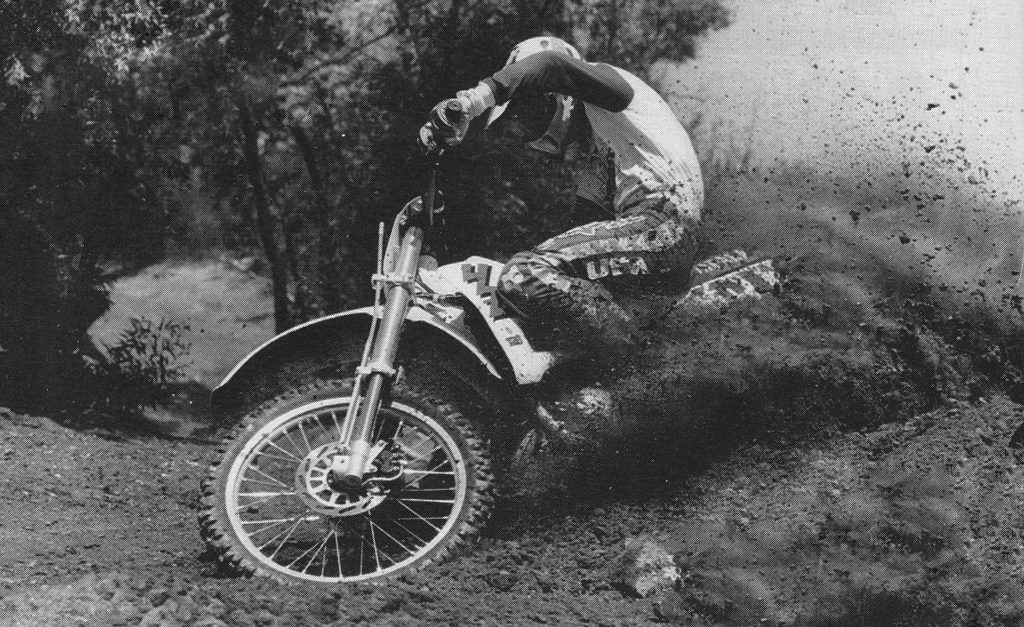

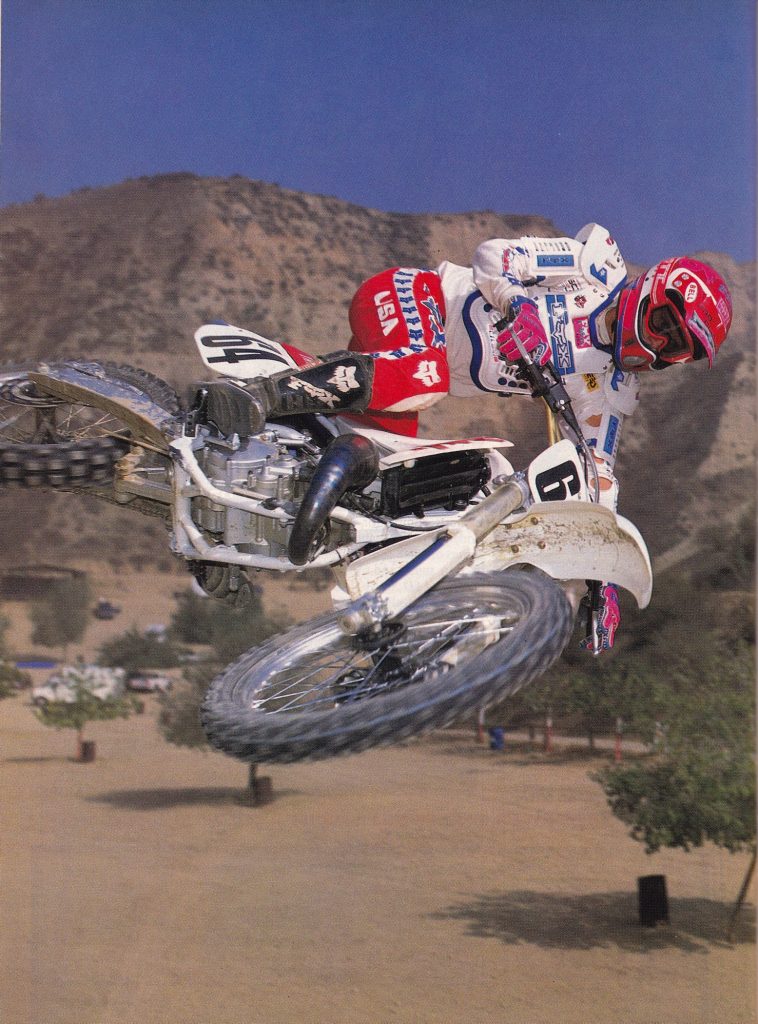

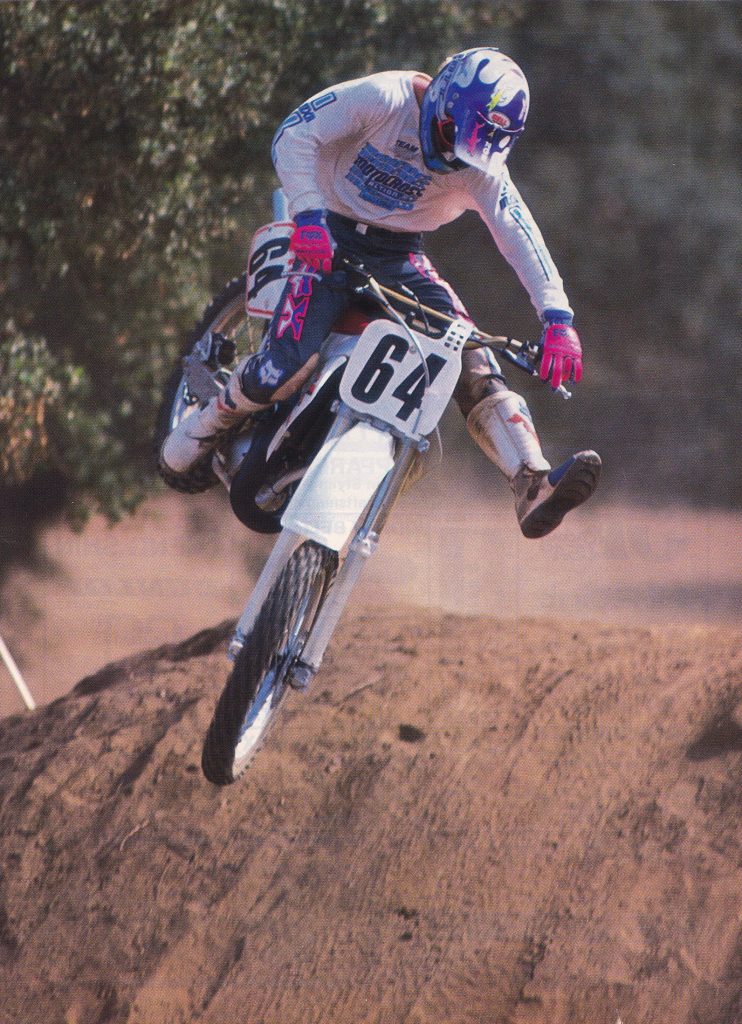

The new chassis for 1989 improved handling greatly on the YZ125. Turning in particular was improved and the bike generally felt more planted on the track. Here Larry Brooks demonstrates the YZ’s new-found berm-busting prowess. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The new chassis for 1989 improved handling greatly on the YZ125. Turning in particular was improved and the bike generally felt more planted on the track. Here Larry Brooks demonstrates the YZ’s new-found berm-busting prowess. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In an attempt to squeeze a bit more top-end power out of their case-reed mill Yamaha decided to increase the size of the carburetor on the new YZ for ‘89. A new 35mm flat-slide Mikuni TM35SS was bolted on that promised improved throttle response and a longer pull on top. In addition to the larger mixer, Yamaha redesigned the airbox for ’89 with a larger airboot and increased internal volume. In addition to being larger overall, the new airbox increased the size of the opening drawing air in and moved the filter access from the side plate to under the seat. Finishing off the quest for more revs was a redesigned exhaust that featured a straighter profile and slightly longer silencer.

While most people enjoyed the YZ’s new layout, taller riders found it a bit cramped at times. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While most people enjoyed the YZ’s new layout, taller riders found it a bit cramped at times. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In the bottom end Yamaha dialed up an all-new clutch and transmission for 1989. In the previous three seasons, these components had been the real Achilles Heel of the YZ125. The motors were fast but the transmissions were stubborn and the clutches were weak. Under power, it was nearly impossible to select the next gear without slipping the clutch and backing off the throttle. On a 125, where keeping it pinned was critical to success, this was not ideal.

For 1989, the YZ125’s 124.8cc motor provided a slightly broader power profile than the ’86-’88 version had. The heavily massaged mill offered slightly less torque but a stronger pull on top. The midrange power was still the best in the class but it no longer fell off a dyno cliff if you tried to stretch out a gear to the next corner. Photo Credit: Yamaha

For 1989, the YZ125’s 124.8cc motor provided a slightly broader power profile than the ’86-’88 version had. The heavily massaged mill offered slightly less torque but a stronger pull on top. The midrange power was still the best in the class but it no longer fell off a dyno cliff if you tried to stretch out a gear to the next corner. Photo Credit: Yamaha

To address these issues Yamaha redesigned the clutch mechanism for smoother engagement and revised the primary reduction ratio in the transmission to slow it slightly in an effort to reduce the old machine’s notchy engagement. New gears were also spec’d for the six-speed transmission that tightened up the spacing in first through fifth gear. In addition to a new mechanism, the clutch received a redesigned two-piece cover for the first time that allowed for access without removing the complete side case.

The more compact layout and slimmer bodywork made the YZ125 feel lighter than ever in 1989. Here Yamaha’s Mike Craig demonstrates its more flickable feel. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The more compact layout and slimmer bodywork made the YZ125 feel lighter than ever in 1989. Here Yamaha’s Mike Craig demonstrates its more flickable feel. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the track, the new YZ125 turned out to be a significant improvement over 1988 in virtually every category. The new motor was slightly less potent off the line than 1988, but its overall powerband was much wider. Low-end torque remained generous for a 125, but the YZ no longer snorted out of the hole like a 200cc Enduro machine. The ’89 version of Yamaha’s case-reed mill started pulling a bit later and continued pulling a bit farther than before. As with 1988, it did its best work in the midrange where it barked with the strongest blast in the class. On top, it tapered off less suddenly than before but it continued to prefer the rider to shift rather than wring it out. Compared to its 125 competition the YZ was stronger down low than the CR and KX and beefier though the middle than all of its rivals. On top, the Honda walked away, and off idle the RM was snappier. Because of its strong low-to-mid power, the YZ was rated by most as the second-best powerband in 1989. It was easier to keep on the pipe than the Honda and faster than the mellow Kawasaki and novice-friendly Suzuki. For true throttle jockeys, the high-strung Honda was better but for most riders, the YZ was a solid choice.

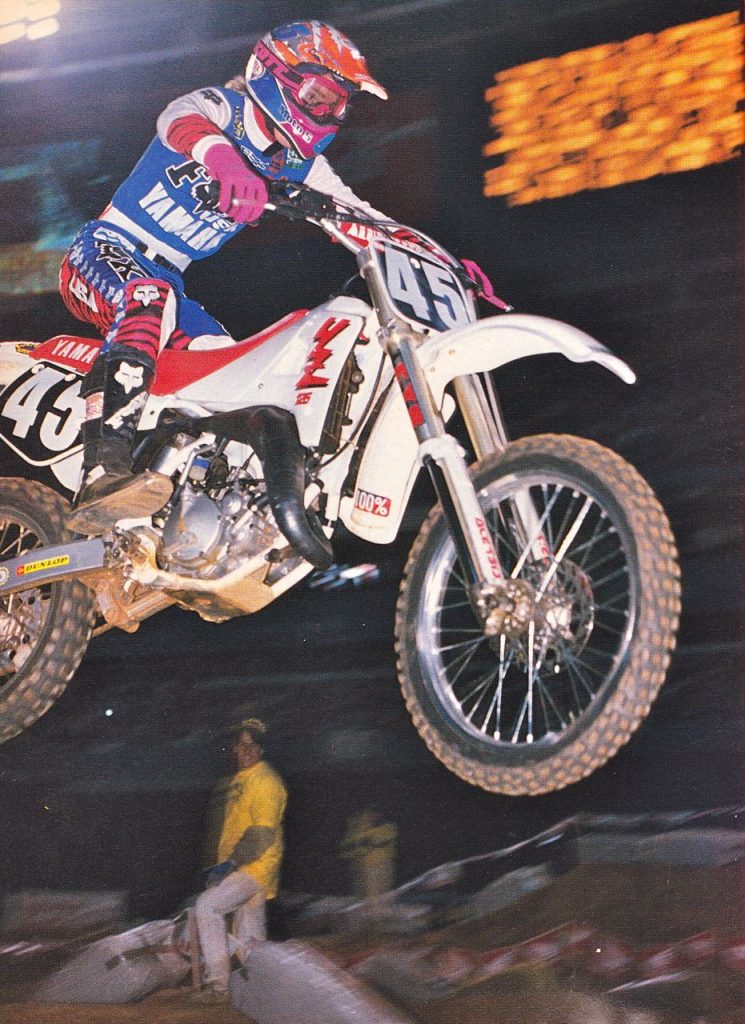

In 1989, Yamaha’s rising star Damon Bradshaw took the new YZ125 to the 125 East Coast Supercross title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1989, Yamaha’s rising star Damon Bradshaw took the new YZ125 to the 125 East Coast Supercross title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the power output of the 1989 YZ125 was highly competitive, its clutch and transmission continued to be a hindrance to its overall appeal. The new transmission offered a slightly smoother action for 1989, but its performance continued to be lackluster compared to its rivals. Power shifting remained a hit-or-miss affair and several riders complained that the new shift lever was difficult to find in the heat of battle. The new clutch did offer a slightly easier pull and improved durability, but overall, the YZ’s clutch and transmission combo continued to be the weak links in an otherwise very competitive motor package.

Unfortunately for Bradshaw and Yamaha, crashes and inconsistency would cause Damon to miss out on the outdoor title by a mere three points to Honda’s Mike Kiedrowski. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Unfortunately for Bradshaw and Yamaha, crashes and inconsistency would cause Damon to miss out on the outdoor title by a mere three points to Honda’s Mike Kiedrowski. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the suspension front, the new YZ was trick but not particularly effective on the track. In 1989, the YZ was the only 125 to move to inverted forks and that gave it the edge in pit cachet if not actual performance. As delivered from the factory, the YZ forks were under sprung and harshly damped. On big hits, they crashed to the stops and bottomed with a thud. Even slower and lighter riders commented on the YZ’s marshmallow springs and thought the bike would have performed better with firmer settings. Compared to the top fork performers in the class such as the KX and RM, the YZ’s only real advantage was in deep ruts were the inverted design offered more clearance. The upside-down forks did offer less flex in the rough than the competition’s conventional designs but without a major upgrade in the springs and damping it was pretty much impossible to take advantage of.

While certainly trick, the new 41mm inverted forks on the YZ125 proved rather lackluster in performance. Overly soft springs and harsh damping held them back from reaching their full potential on the track. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While certainly trick, the new 41mm inverted forks on the YZ125 proved rather lackluster in performance. Overly soft springs and harsh damping held them back from reaching their full potential on the track. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the shock side, the new Kayaba damper proved to be better set up than the forks. The overall spring rate and damping settings were well within the ballpark for most pilots likely to find their way onto a YZ125. It was well-controlled on hard landings but many riders complained of a harsh feeling in the mid-stroke that detracted from its overall plushness. Small chop also seemed to flummox its damping at times and some testers noted a hint of the old Yama-hop still in its DNA. Because of the bike’s light weight and modest power output, the YZ could still be raced with the stock components in place, but for most riders, it was the least well-sorted suspension package in the 1989 125 class.

The redesigned KYB shock on the ’89 YZ125 proved to be better sorted than the new inverted forks had been. Both the springs and damping settings were in the ballpark for most 125 racers and the bike could at least be raced without a major overhaul. A slight kick in the rough and a bit of mid-stroke harshness were the main demerits that kept it a step below the best rear ends in 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The redesigned KYB shock on the ’89 YZ125 proved to be better sorted than the new inverted forks had been. Both the springs and damping settings were in the ballpark for most 125 racers and the bike could at least be raced without a major overhaul. A slight kick in the rough and a bit of mid-stroke harshness were the main demerits that kept it a step below the best rear ends in 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In the chassis department, the YZ was much improved for 1989. The new beefier frame and sturdier inverted forks gave the bike a more solid feel and dispelled most of the vague steering habits of the old chassis. On hardpack, the YZ went where it was pointed and felt far more planted than the year before, but in sand and mud that surefootedness went away slightly. It was better than previous YZs but still not as accurate as carvers like the RM and CR. As in 1988, its best handling trait was its stability. Unlike the twitchers in the class, the YZ could be bombed down a whooped straight without any fear of the bars being wrenched from your hands. With the mismatched stock suspension settings in place the bike could get a bit unsettled at times but once you stiffened up the forks and evened things out the YZ was one of the most stable machines in the class.

While an able flier, aerial antics like this on the stock YZ were likely to greet you with a thud from the front forks on touchdown. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While an able flier, aerial antics like this on the stock YZ were likely to greet you with a thud from the front forks on touchdown. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Aiding the YZ’s handling was its new layout, which lowered the center of gravity and made it easier for pilots to keep forward in turns. The new tank was slim and the flatter seat made it easy to move around when necessary. Compared to 1988, the bike felt smaller, more compact, and lighter, in spite of the fact that the weight was nearly unchanged. Most riders liked the new “low boy” layout but some taller riders did complain that the revised ergonomics were a bit cramped.

While the YZ’s power output was more than competitive in 1989, its recalcitrant transmission continued to be the weak link in an otherwise strong motor package. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While the YZ’s power output was more than competitive in 1989, its recalcitrant transmission continued to be the weak link in an otherwise strong motor package. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the details front, the new YZ was much improved for 1989. The new quick-access clutch cover and removable frame spar made servicing easier and the new softer chain buffer stopped the clatter that had been a constant companion on previous YZs. The engineers also ditched the majority of the problematic Phillips screws found on earlier YZs in favor of much more durable hex-head bolts for 1989 (hallelujah!). The new pipe tucked in far better than before and hung down less at the header. This made it far less likely to be damaged in a crash and less prone to roasting your inner calf in a long moto. The new brakes offered excellent power and an improved feel over the slightly grabby ’88 versions. Pretty much everyone loved the looks of the new bodywork but some riders did complain about catching their boots on the left-side shroud. Unfortunately, the upper shroud mount was not really up to this abuse and it was easy to pull the shroud loose of its mounting.

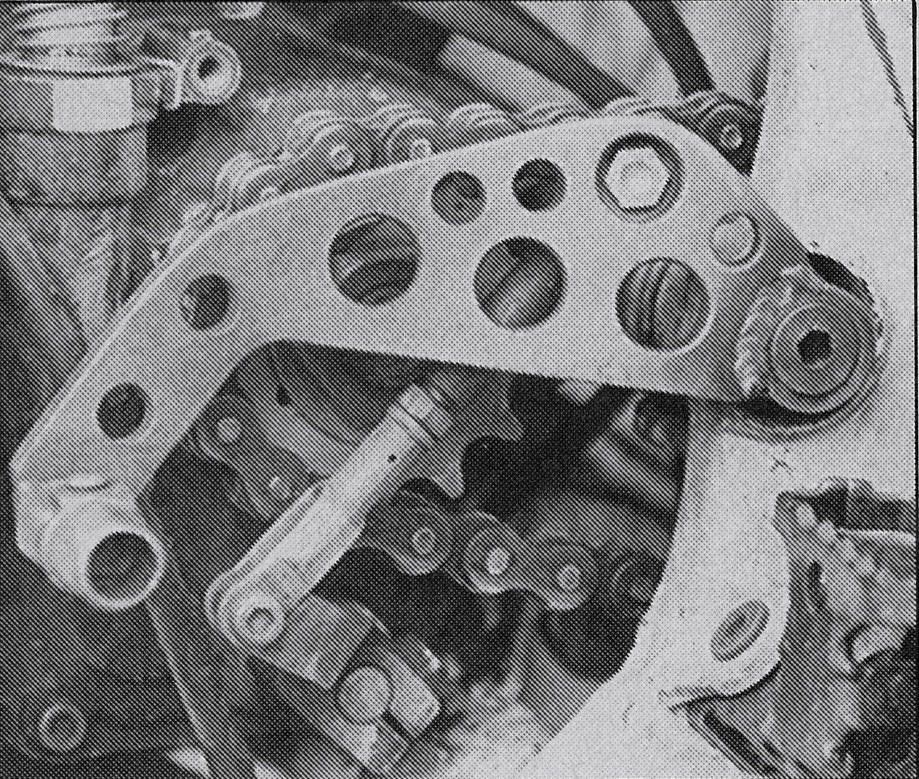

Gyro Gearloose: In the late eighties, Yamaha’s shifting woes became such an issue that companies like Race Tech designed complicated new shifting mechanisms to reduce effort and provide more positive engagement. I ran one of these Race Tech shifters on both my 1988 and 1989 YZ125s and I can tell you they may have looked a bit crazy, but they made a huge improvement in the shifting action on these machines. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Gyro Gearloose: In the late eighties, Yamaha’s shifting woes became such an issue that companies like Race Tech designed complicated new shifting mechanisms to reduce effort and provide more positive engagement. I ran one of these Race Tech shifters on both my 1988 and 1989 YZ125s and I can tell you they may have looked a bit crazy, but they made a huge improvement in the shifting action on these machines. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the less-impressive side were the YZ’s bars (bent for an orangutan and butter-soft), grips (palm-eaters, these), cranky shifting (the crankiest), and wimpy fork springs. While not quantifiable, many riders also commented on the YZ’s generally loose feel. Compared to machines like the CR125R, the YZ seemed to lose that “new” feeling faster and generally seemed worn-out more quickly. Thankfully, this did not seem to hinder its reliability and the YZ proved one of the toughest machines to break in 1989. Like the Energizer Bunny, the YZ just kept running and running, but it did so with more of a clapped-out feel than some of its rivals.

Yamaha’s all-new YZ125 had a lot going for it in 1989. It was easier to ride than the rev-happy Honda, more fun than the mellow Kawasaki, and faster than the novice-friendly Suzuki. If only it had shifted worth a damn and not come sprung for a mini-pilot, it may have finally upset Honda’s stranglehold on the top spot in the late-eighties 125 standings. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Yamaha’s all-new YZ125 had a lot going for it in 1989. It was easier to ride than the rev-happy Honda, more fun than the mellow Kawasaki, and faster than the novice-friendly Suzuki. If only it had shifted worth a damn and not come sprung for a mini-pilot, it may have finally upset Honda’s stranglehold on the top spot in the late-eighties 125 standings. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Overall, Yamaha came to play in 1989 with a much-improved YZ125. The new machine offered improved power, tighter handling, and the latest in works technology. With its trick inverted forks, YZM-styling, and 19” rear wheel, Yamaha signaled that they were serious about gunning for Honda in the 125 class. The 1989 YZ125 offered competitive power, sano looks, and much-improved handling. Unfortunately, it also offered poorly set up suspension and a cantankerous cog-box. Despite this, many riders still found the YZ125 to be an attractive alternative to the blazing-fast but demanding CR125R. Fast, fun, and somewhat lacking in finesse, the ’89 YZ125 was a solid package in need of a bit more polish.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com