For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki’s all-new KX250 for 1988.

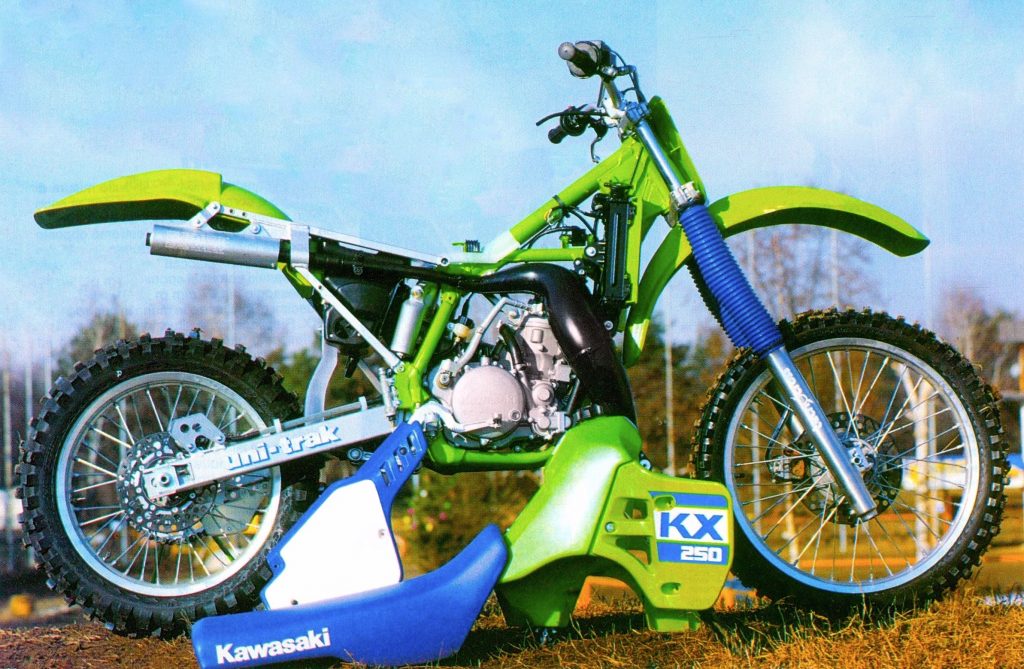

After introducing an all-new KX250 in 1987, Kawasaki was back once again with a completely redesigned 250 Kwacker for 1988. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

After introducing an all-new KX250 in 1987, Kawasaki was back once again with a completely redesigned 250 Kwacker for 1988. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The 1980s were a time of great success for Kawasaki. After languishing at the back of the motocross pack throughout most of the seventies, they came roaring back with a series of ever-improving machines during the Reagan decade. First in the 80 class, then later in the 125s and the 500s, the green machines went from also-rans to top contenders. In the 250 division, however, that success proved to be more elusive. Year in and year out, the KX250s had provided the power to win, without the handling and suspension finesse to take advantage of all those ponies.

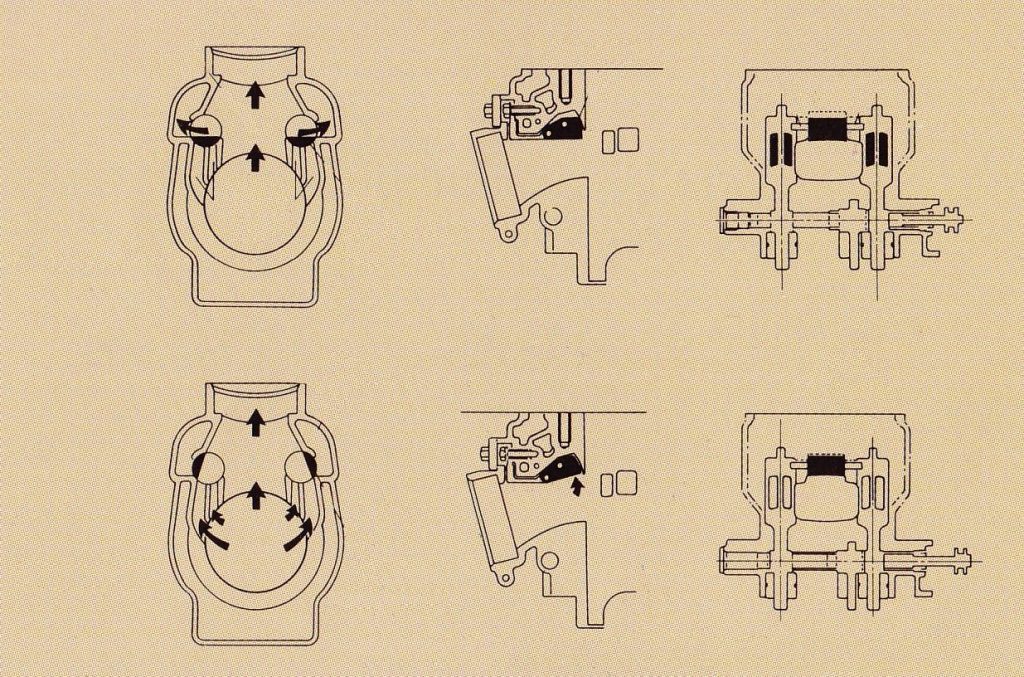

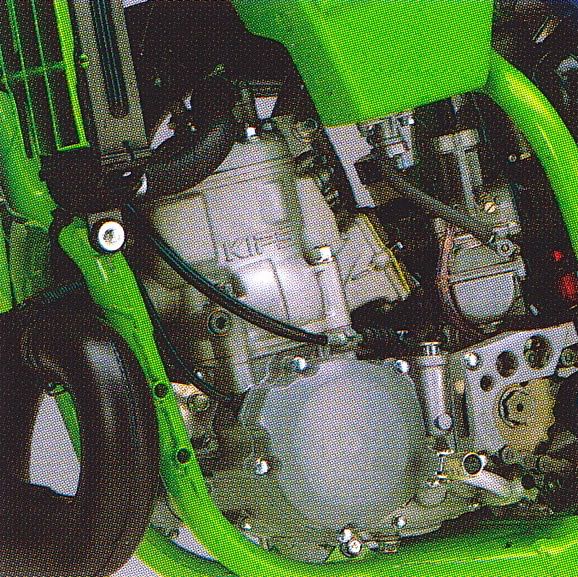

KIPS: For 1988, Kawasaki perfected the modern “power valve” by adding a third valve to alter the height of the exhaust port as well as vary the volume of the exhaust pipe. By combining the technology used in Honda’s ATAC and Yamaha’s YPVS, Kawasaki was able to set the foundation for the next two decades of power valve design. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

KIPS: For 1988, Kawasaki perfected the modern “power valve” by adding a third valve to alter the height of the exhaust port as well as vary the volume of the exhaust pipe. By combining the technology used in Honda’s ATAC and Yamaha’s YPVS, Kawasaki was able to set the foundation for the next two decades of power valve design. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1987, that had once again been the KX250’s story as the green deuce-and-a-half pumped out tons of power, but was unfortunately saddled with a grim set of forks. With a tractor-like powerband and the slimest ergonomics in the class, the ’87 KX250 had its devotees, but its lack of a cartridge fork and rather pedestrian handling held it back from capturing the top spot in the 250 division. Fun, fast, and feathery-feeling, it was highly competitive, but not quite up to toppling Honda’s omnipotent CR250R.

All-new bodywork for 1988 revised the looks and increased the width of the KX250 considerably. While many riders questioned the wisdom of this change when comparing the green machine to the new razor-thin Honda, off-roaders did appreciate the additional 0.6 gallons of capacity the new jumbo tank afforded. Photo Credit: Me

All-new bodywork for 1988 revised the looks and increased the width of the KX250 considerably. While many riders questioned the wisdom of this change when comparing the green machine to the new razor-thin Honda, off-roaders did appreciate the additional 0.6 gallons of capacity the new jumbo tank afforded. Photo Credit: Me

For 1988, Kawasaki set about finally capturing the mantle of top 250 in the land by scrapping the ’87 design and introducing a redesigned KX250. Considering the 1987 machine had been a total redesign as well, this was no small amount of effort by the green team. In 1987, Kawasaki had finally moved away from their original “dog bone” style Uni-Trak linkage on the KX250 and adopted a Honda Pro-Link style bottom link design. This new layout lowered the center of gravity considerably and freed up room to enlarge the airbox for additional power. For 1988, Kawasaki kept this new layout and added several more chassis changes aimed at improving the KX’s performance. Just as in ’87, the KX’s frame was crafted out of tough chromoly steel but the 1988 version featured substantial bracing to critical areas like the steering stem and swingarm pivot. This was done to reduce flex and improve chassis precision. The overall geometry was also altered slightly with the new chassis employing slightly more trail (9mm) than 1987. Mated to the new frame was a redesigned Uni-Trak linkage, which featured new ratios to deliver a more progressive action. This new layout also moved the link arms up slightly to prevent them from catching on obstacles under full compression. To further improve chassis precision Kawasaki redesigned the rear swingarm for 1988 to be stronger overall and much more resistant to torsional flex under heavy loads. Both the height and width of the swingarm were increased and an additional internal brace was added to beef up its construction. To prevent axle movement the chain adjustment mechanism was also redesigned and moved to an internal configuration. Aiding the stopping duties for 1988 were all-new brakes both front and rear. Changes to the rear were aimed at reducing the gabbiness of the powerful but light-switch-like ’87 binder. Up front, a revised master cylinder offered a new ratio for more power and a new “shorty” lever for increased comfort. In a weight and cost-cutting measure, the brake line was changed to nylon from the braided steel of ’87. Finishing off the chassis changes for 1988 was a redesigned alloy subframe, which could be removed to aid shock servicing, and a fresh coat of green paint, which replaced the silver of previous KX machines.

An all-new chassis for 1988 featured a beefed-up steering stem, swingarm, and swingarm pivot for increased strength and a reduction in torsional flex. Photo credit: Motocross

An all-new chassis for 1988 featured a beefed-up steering stem, swingarm, and swingarm pivot for increased strength and a reduction in torsional flex. Photo credit: Motocross

KXs bound for other markets in 1988 received a set of blue side plates instead of the traditional green found on the US models. Only the KX80 kept the international blue look in the ’88 US lineup. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

KXs bound for other markets in 1988 received a set of blue side plates instead of the traditional green found on the US models. Only the KX80 kept the international blue look in the ’88 US lineup. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the suspension end of the equation, the ’88 KX250 featured major upgrades both front and rear. In 1987, this had been the real weak link in an otherwise highly competitive package and Kawasaki knew this shortcoming would need to be addressed if the KX was going to best its rivals. Starting in 1986, Honda had begun offering cartridge internals on their CR250R’s forks and these works-style dampers had immediately rendered all other forks in the class obsolete. The cartridge design offered reduced aeration, improved damping control, and a wider range of operation over the old-style damper-rod designs. In 1986 and 1987, Kawasaki had resisted the move to the more sophisticated forks by trying to employ less-costly workarounds. The Kayaba Travel Control Valve (TCV) forks made lots of promises that its on-track performance could not back up and both Yamaha and Kawasaki suffered in the ’87 standings for it. In 1988, Kawasaki finally decided to get with the program by moving to a cartridge design on the KX250. All-new for 1988, these 43mm conventional Kayaba cartridge units pumped out 11.8 inches of travel and offered 16 positions for compression adjustability. This put it on par with the 43mm Showa units found on the ’88 Honda CR250R but still a tick behind the more sophisticated KYB units found on the ’88 RM250, which offered rebound adjustments to go with the compression selector.

The 1988 season was a great time to be shopping for a 250 machine from Japan. All four entries were redesigned with every model making significant improvements in one way or another. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The 1988 season was a great time to be shopping for a 250 machine from Japan. All four entries were redesigned with every model making significant improvements in one way or another. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1987, the KX250’s shock had been more successful than its forks, but it still lagged behind the top performers in the class. It was slightly harsh in the mid-stroke and prone to bending shock shafts when ridden hard. For 1988, Kawasaki looked to address both of these issues by installing an all-new shock for the KX250. To rectify the bending issues from 1987, Kawasaki’s engineers upped the diameter of the shock shaft by 2mm to the same 16mm used by Jeff Ward on his factory Kawasaki in ’87. In addition to the larger shaft, an all-new damping system was introduced to provide a more consistent oil flow through the shim stacks for a smoother feel. Rear-wheel travel remained at 13 inches with 16 adjustments available for compression and rebound control.

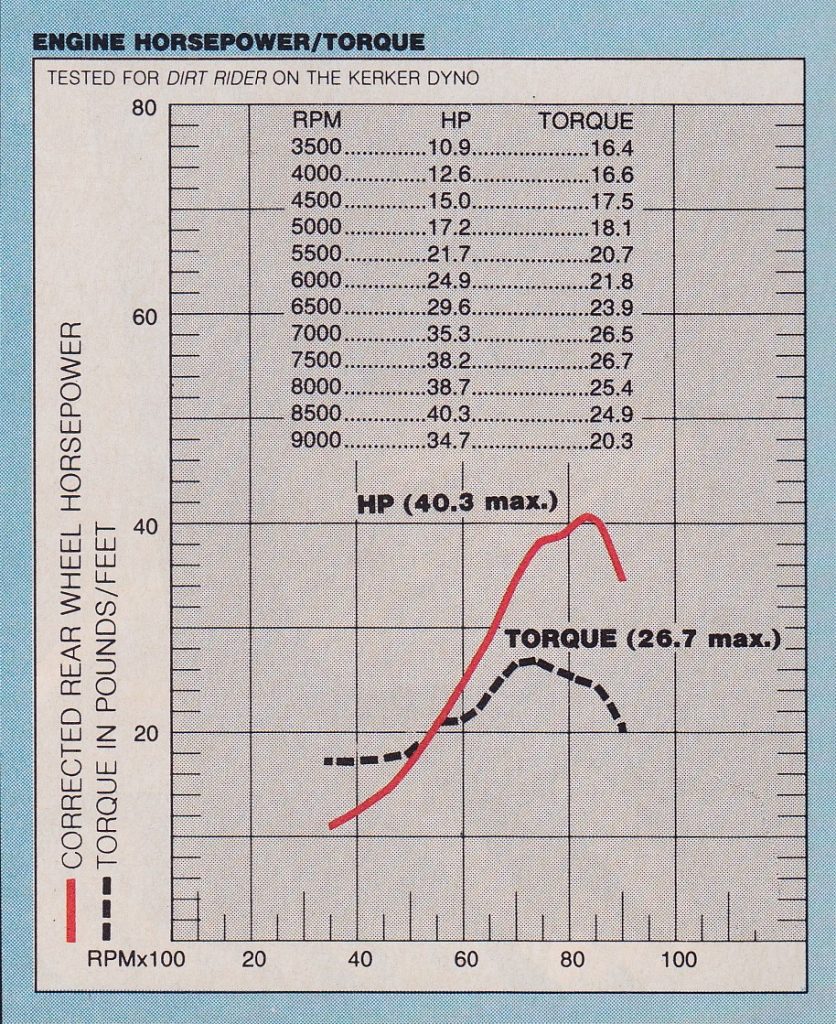

On the dyno Kawasaki’s revised triple-KIPS motor pumped out nearly two horsepower more than 1987. On the track, it romped on the completion with a chunky low-end and massive midrange hit. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the dyno Kawasaki’s revised triple-KIPS motor pumped out nearly two horsepower more than 1987. On the track, it romped on the completion with a chunky low-end and massive midrange hit. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

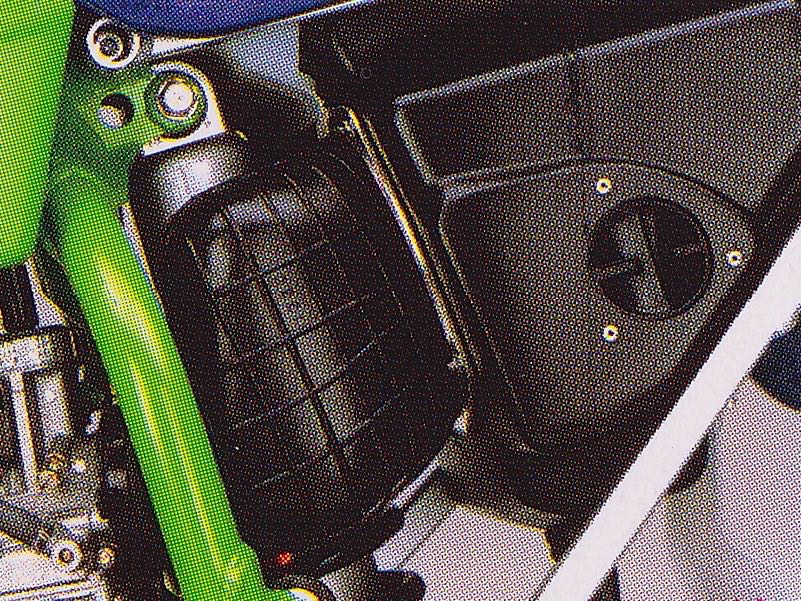

A super-trick all-new airbox made venting a thing of the past by adding a rotating shutter valve that could be opened to increase airflow in the dry and closed when things got muddy. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

A super-trick all-new airbox made venting a thing of the past by adding a rotating shutter valve that could be opened to increase airflow in the dry and closed when things got muddy. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the motor side, Kawasaki once again went all-in with a complete redesign of their 250 powerhouse. In 1987, the KX250 had offered a powerband that pumped out tons of low-to-mid power. The super-responsive motor went at the slightest crack of the throttle and ran the exact opposite of Honda’s rev-it-to-the-moon CR250R. Many riders loved this chunky style of power but fast guys did lament its utter lack of revs. For 1988, Kawasaki tried to extend the pull of their well-regarded mill by completely redesigning their Kawasaki Integrated Powervalve System (KIPS). Originally introduced in 1985, the original KIPS consisted of two small sub-ports and a small exhaust resonance chamber. At low rpm, the two sub-ports closed and redirected the exhaust to the resonance chamber in the same manner as Honda’s ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber). This boosted low-end power by mimicking the effects of installing a “torque” pipe to the exhaust. As rpm rose, a centrifugal-ball governor opened the two sub-ports and closed off the resonance chamber to increase exhaust flow for increased top-end power.

Bringing the thunder: In 1988, no motor in the 250 class was even close to the blistering performance offered by Kawasaki’s all-new KX250. Slightly smoother down low than in 1987, the new mill pulled much harder through the middle and longer on top. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Bringing the thunder: In 1988, no motor in the 250 class was even close to the blistering performance offered by Kawasaki’s all-new KX250. Slightly smoother down low than in 1987, the new mill pulled much harder through the middle and longer on top. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

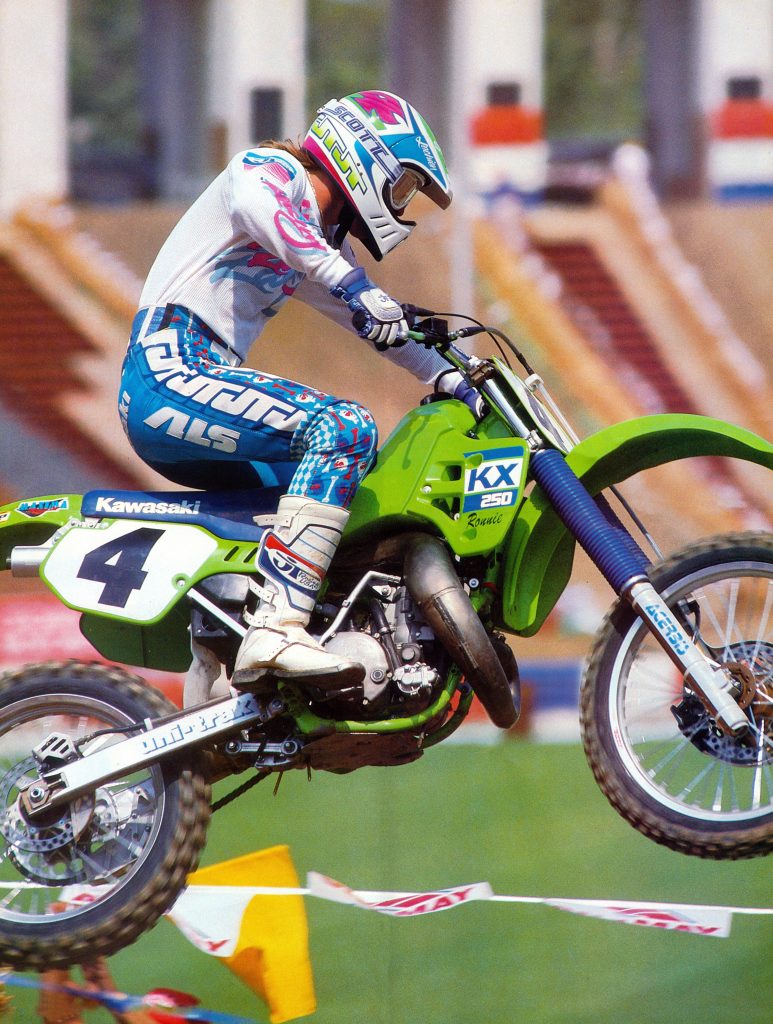

While some riders lamented the move to bulkier bodywork in 1988, taller riders like Ron Lechien found it offered them more control by making it easier to hold onto the machine in the rough. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

While some riders lamented the move to bulkier bodywork in 1988, taller riders like Ron Lechien found it offered them more control by making it easier to hold onto the machine in the rough. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

New larger footpegs and a sano folding brake lever were two welcome additions on the KX250 for 1988. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

New larger footpegs and a sano folding brake lever were two welcome additions on the KX250 for 1988. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

For 1988, Kawasaki looked to increase the effectiveness of the KIPS by adding a third mechanism to the design. In addition to the original sub-ports and resonance chambers, a new variable valve was added to the main exhaust port. This new valve was designed to alter the port timing in the same way as Yamaha’s YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) and Honda’s HPP (Honda Power Port). In addition to the new KIPS mechanism, an all-new combustion chamber was designed that promised to provide a more uniform burn and a reduction in the infuriating plug fouling of ’87. One of the reasons for the KX’s prodigious tractor-like power in ’87 had been Kawasaki’s move to a longer stroke and the ’88 machine maintained this 67.4 x 70.0mm bore and stroke configuration but added a bit of weight to the crankshaft to increase the chug factor. Overall displacement remained unchanged at 249cc but the ’88 rendition did offer a slightly lower compression ratio (10.1:1 in ’88 vs. 10.6:1 in 1987) than the year before.

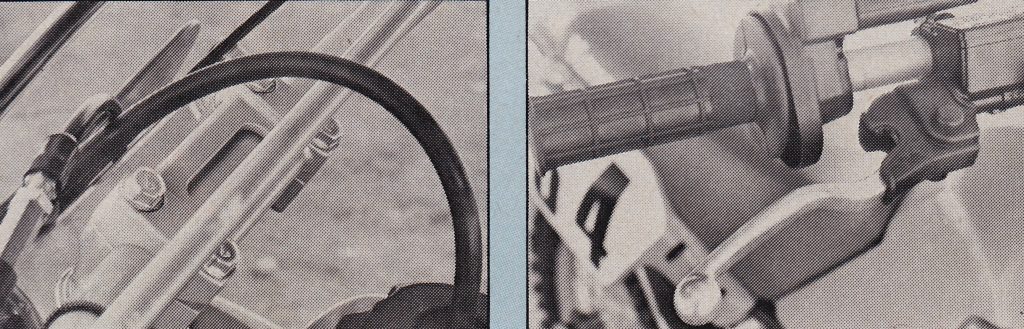

A new one-piece bar clamp prevented the bars from twisting in a crash and a new “shorty” brake lever improved the braking feel. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

A new one-piece bar clamp prevented the bars from twisting in a crash and a new “shorty” brake lever improved the braking feel. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

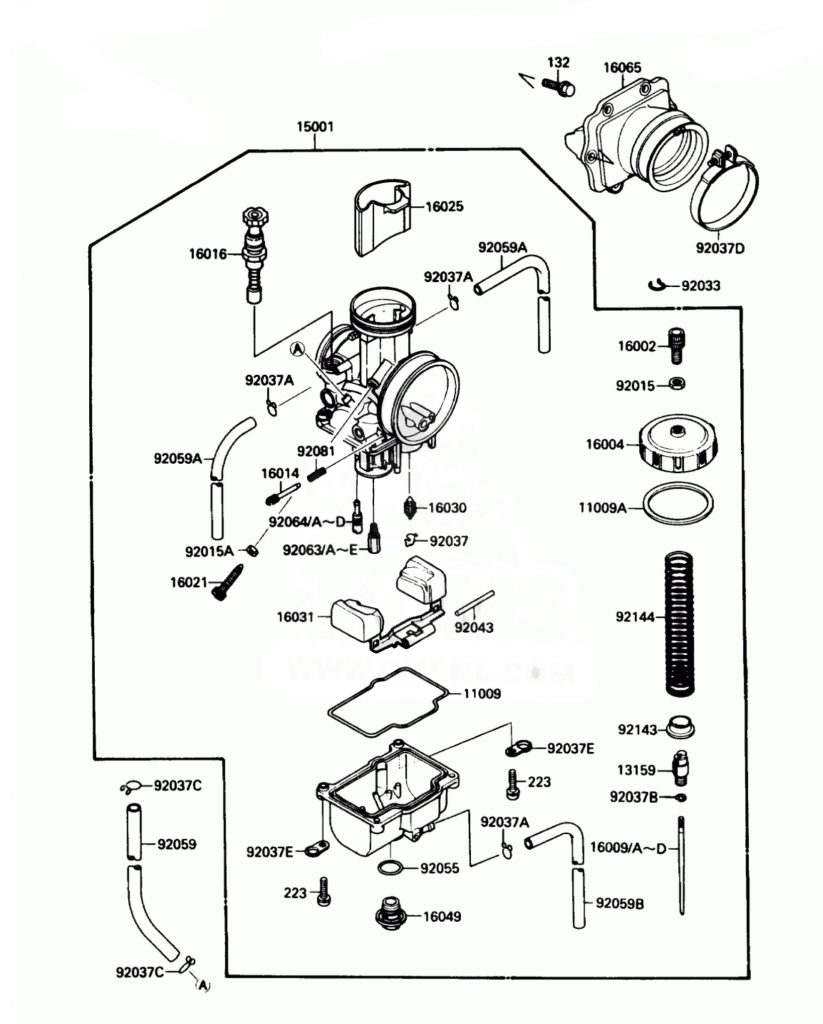

In addition to the new top-end, the ’88 KX250 featured an all-new intake system. A new airbox was installed that increased volume and added a trick set of rotating valves that could be opened or closed based on track conditions. Carburation duties moved from the “R-bottom” Mikuni of 1987 to Keihin’s all-new “crescent-slide” PWK39 for 1988. This new mixer was said to offer the most unobstructed airflow of any carburetor available and also allowed the pilot jet to be positioned more closely to the main jet for a smoother transition from the low to the high-speed circuit. Finally, a new eight-pedal carbon-fiber reed-valve fed fuel into the cylinder. Matched to the new intake was a redesigned exhaust system that was tuned to improve top-end power over 1987.

While not a shredder, the new KX250 did turn with far more accuracy than the previous Kawasaki 250s. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

While not a shredder, the new KX250 did turn with far more accuracy than the previous Kawasaki 250s. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

In 1988, this was the most advanced engine available in the 250 class and that technological advantage showed on the track. Photo Credit: Kawasaki.

In 1988, this was the most advanced engine available in the 250 class and that technological advantage showed on the track. Photo Credit: Kawasaki.

On the bottom end, an all-new clutch was added that featured a redesigned engagement arm that repositioned the pivot points for smoother action. Both the pushrod and plates themselves were also modified to prevent sticking and ensure a more solid feel at the lever. If it did become necessary to swap the plates, an all-new two-piece cover made servicing much faster and easier than in the past.

Because of its girthy midsection, prodigious power, and a seven-pound weight gain for ’88 many riders compared the new KX250’s feel with that of a 500. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Because of its girthy midsection, prodigious power, and a seven-pound weight gain for ’88 many riders compared the new KX250’s feel with that of a 500. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Of all the changes made in 1988, perhaps the most dramatic was the layout of the machine. In 1987, the KX250 had been by far the slimmest bike in its class. Its bodywork was razor-thin and its ergonomics made it feel more like a 125 than a 250 on the track. While most riders had loved its slim feel, some pros (most notably Jeff Ward and Ron Lechien) had felt the midsection was too slim to get a good hold on in the rough. Off-roaders also lamented the half-gallon reduction in capacity the tank suffered in 1987. For 1988, Kawasaki remedied these concerns by completely redesigning all of the bodywork on the KX250. A new tank was spec’d that provided 0.6 gallons more capacity and increased the width of the machine considerably. New side plates were also installed that matched the beefier new profile and a redesigned seat was installed that offered a flatter and more squared-off shape. In the rear, a new fender was designed that carried up much higher towards the back of the seat. This was done to provide a smoother transition when sliding rearward but it did give the fender a slightly odd appearance.

The absurdly soft foam used in the new KX’s seat was panned by all. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The absurdly soft foam used in the new KX’s seat was panned by all. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the track, the all-new KX turned out to be a very competitive 250 motocross weapon. The new motor accomplished all of Kawasaki’s goals and turned out to be the best 250 engine available in 1988. The new heavier crank mellowed out the 1987’s abrupt low-end hit and made the KX much easier to control. Out of turns, it no longer tried to jerk your arms out of their sockets and hooked up much better on slippery surfaces. The midrange was still extremely potent, however, and it was best to hold on tight once the bike came on the pipe. Once the KIPS valves opened the KX pulled with such ferocity that many riders compared it to an Open bike. At the top-end, the new motor pulled farther than before but the majority of its thrust was still found in the midrange. On the dyno, it pumped out nearly two more horsepower and two more pound-feet of torque than 1987, but on the track, it felt like double that amount. It was a rompin’, stompin’ powerhouse of a motor that chugged, churned, and roosted its way to the front. In 1988, no other motor was even close to the big-bore vibes the KX pumped out.

The new 43mm Kayaba cartridge forks for 1988 improved the KX’s suspension performance ten-fold over 1987. While not as perfectly damped as the units found on Suzuki’s RM250 they were easily the best forks ever offered on a green machine. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The new 43mm Kayaba cartridge forks for 1988 improved the KX’s suspension performance ten-fold over 1987. While not as perfectly damped as the units found on Suzuki’s RM250 they were easily the best forks ever offered on a green machine. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the suspension front, the KX was much improved in some areas and a bit of a push in others. Up front, the new 43mm Kayaba cartridge forks offered a much smoother ride than in 1987. They absorbed big hits well and tackled most track obstacles without a whimper. Both the spring rates and valving were well suited for most riders below the pro class and the bike could be raced with the forks in stock condition without any major issues. The only complaint with their operation was a hint of the old fork’s harshness in the mid-stroke, but overall, it was rated the second-best front end of 1988 behind only the excellent silverware found on the Suzuki RM250.

The new Uni-Trak rear suspension for 1988 did not prove to be as effective on the tracks as the updated forks. Harsh and prone to packing, the KYB shock needed a re-valve if you hoped to get the most out of your new KX250. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The new Uni-Trak rear suspension for 1988 did not prove to be as effective on the tracks as the updated forks. Harsh and prone to packing, the KYB shock needed a re-valve if you hoped to get the most out of your new KX250. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the rear, things were not quite as rosy. The all-new Uni-Trak rear suspension turned out to be a rather lackluster performer with damping settings that held it back from performing its best. In the rough, it was harsh on compression and prone to packing up on successive hits. This gave it a dead feel as it thudded into bumps instead of recocking before the next impact. It worked well on big hits but small chatter and whoops played havoc with its overly aggressive damping settings. It was not unraceable, but it was far less plush than machines like the Suzuki RM and Yamaha YZ. If you wanted to get the most out of your new ‘88 KX250, a shock re-valve was most definitely in order.

With its generous 2.6-gallon tank, great stability, and available wide-ratio transmission kit, the KX made a very capable off-road racer in 1988. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

With its generous 2.6-gallon tank, great stability, and available wide-ratio transmission kit, the KX made a very capable off-road racer in 1988. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

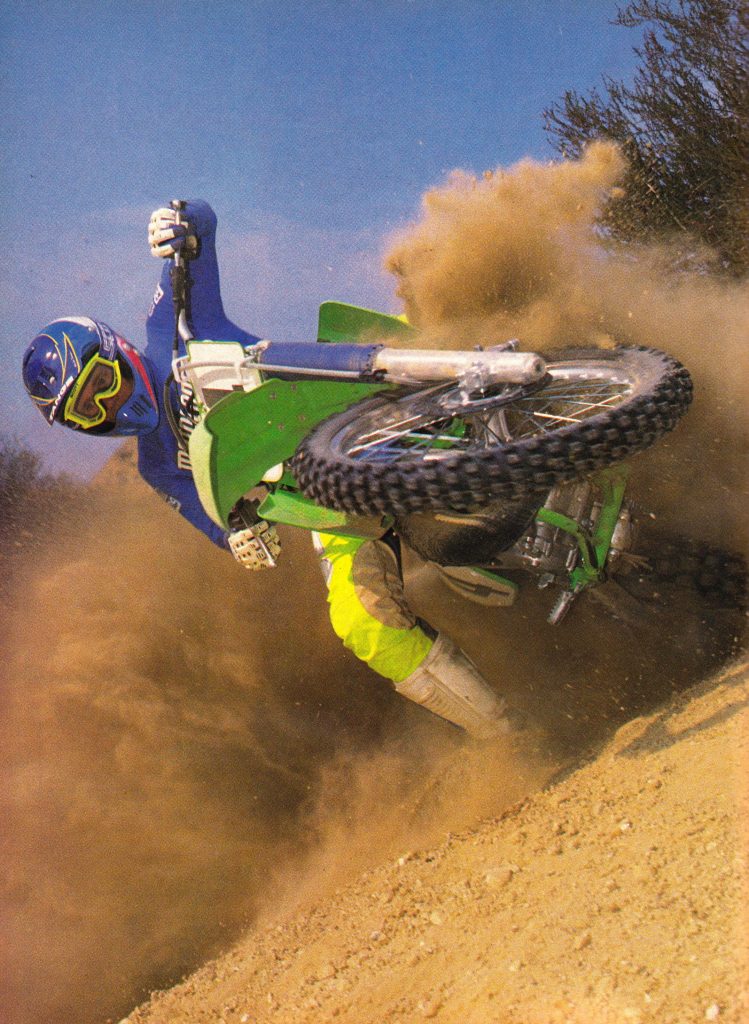

Talented riders like “Wild” Willy Simons could get away with a lot on the new KX but there was no getting around its hard-hitting power and girthy feel. For riders looking for a less-demanding package, the redesigned ‘88 RM250 and YZ250 offered most of the KX’s performance in an easier to manage package. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

Talented riders like “Wild” Willy Simons could get away with a lot on the new KX but there was no getting around its hard-hitting power and girthy feel. For riders looking for a less-demanding package, the redesigned ‘88 RM250 and YZ250 offered most of the KX’s performance in an easier to manage package. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

On the handling front, the new KX was an excellent middle-of-the-road performer. The new stiffer chassis and revised geometry made the ’88 KX the sharpest turning Kwacker of all time, but it was still not a carver by Honda standards. What it did do much better than the Honda was go straight and the KX offered one of the best combinations of stability and agility in the class. Some riders did miss the old bike’s super-slim layout and commented that the pudgy ergos and monster motor made the KX feel more like a 500 than a lightweight 250. Of course, the additional seven pounds the KX picked up for 1988 did not help this Rubenesque feel. While this did not cripple its competitiveness on the track, it did make the KX more of a handful for smaller and lighter riders. The larger and taller you were, the more likely you were to jive with the KX’s new plus-sized feel.

A trick new “crescent” slide PWK39 Keihin carburetor was one of the keys to the KX’s excellent power in 1988. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

A trick new “crescent” slide PWK39 Keihin carburetor was one of the keys to the KX’s excellent power in 1988. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the detailing side, Kawasaki made solid strides in some areas and suffered from familiar foibles in others. The new airbox with the rotating air vets was super trick (why don’t we still see this design today?) and made mud races less of a worry. The new one-piece bar clamps prevented the bars from twisting in a crash and helped give the KX a more precise feel. The footpegs were also bigger for ’88 and everyone enjoyed the increased support they afforded. Most riders loved the bike’s new color scheme with the green frame and silver motor. This was reminiscent of the super-trick DMC Kawasaki machines of the time and a welcome refresher to the often stodgy KX aesthetics. Other markets received new blue side plates in 1988, but for some reason (reports at the time had Jeff Ward giving the new look the thumbs down) Kawasaki decided to stick with green for all the KXs bound for the US (except the KX80 for some unknown reason).

Factory Kawasaki’s Jeff Ward used the all-new KX250 to race to his second 250 National Motocross title in 1988. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

Factory Kawasaki’s Jeff Ward used the all-new KX250 to race to his second 250 National Motocross title in 1988. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

The redesigned clutch offered an easier pull at the lever but the unit continued to offer a grabby engagement and sub-par plate life. At least servicing it was easier with the new two-piece cover. The new front brake offered lots of power and most riders liked the new shorty lever but many calipers suffered from sticking pistons. Honing out the piston cavity and keeping a close eye on the easily bent alloy caliper bracket were the best ways to prevent a possibly painful braking snafu. In the rear, the braking feel was much improved with much less of the “light switch” engagement that had annoyed riders in ’87. Off-roaders loved the new larger tank but no one loved the KX’s incredibly brittle plastic. The fenders, shrouds, gas cap, and side plates were easily cracked and far less durable than the plastic seen on any of the competition. Most bolts were also of the pot-metal variety, with the ones used to secure the seat and subframe being the worst offenders. Speaking of the seat, this was probably the most universally panned part of the ’88 makeover. While the shape was reasonably inoffensive, the loaf of Wonder Bread Kawasaki installed as seat foam was not. Even when new, it sagged appreciably and locked the rider in place. Once ridden on, it immediately reverted to the consistency of a warm marshmallow and placed the rider’s coccyx directly on the frame rails. If you were in favor of avoiding a bruised bum then an aftermarket upgrade was a must. Lastly, the alloy subframe, while super light and trick, was also easily damaged and prone to stripping out the inserts that secured the seat. Adding a nut to the seat bolts and installing a Race Tech guard (or fabricating your own) to prevent the flimsy stock chain from chewing through the left subframe strut were both advisable insurance measures.

Bigger, beefier, and more brawny than before, Kawasaki’s KX250 offered lots of performance in 1988. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Bigger, beefier, and more brawny than before, Kawasaki’s KX250 offered lots of performance in 1988. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Overall, the 1988 Kawasaki KX250 turned out to be the most competitive green machine ever to grace the 250 class. It was big, burly, and slightly brittle, but also wicked fast and good handling. The redesigned triple-KIPS motor was the class of the 250 field and the new cartridge KYB forks finally brought the KX out of the suspension dark ages. If only it had offered a shock that worked and a bit less suet it might have captured Kawasaki its first shootout victory in the 250 division. In an era where slimmer, lighter and smaller were all the rage, the ’88 KX250 went a different direction and left it up to you to decide what path led to the victory podium.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com