For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at one of the most iconic machines of the 1980s, Honda’s 1989 CR250R.

After wowing the industry with an all-new CR250R in 1988, Big Red was back with a refined and refreshed deuce-and-a-half for 1989. Photo Credit: Honda

The mid-to-late eighties were a great time to be riding red in the 250 class. Starting in 1983, the CRs were consistently some of the best machines available in the deuce-and-a-half division. Sharp turning, powerful motors, and sano looks were hallmarks of the red machines in this era. In 1986, Honda utterly dominated the 250 division with an all-new motor and the most advanced suspension in the class. The CR’s works-like Showa cartridge forks and incredibly broad power made the red machine the unanimous choice for serious racers.

After two years of 250 class dominance the revamped 1988 CR250R turned out to be a bit of a disappointment. While the new “low boy” layout was a hit, changes made to the motor and suspension for ’88 left many riders longing for the more effective ’87 CR. Photo Credit: Honda

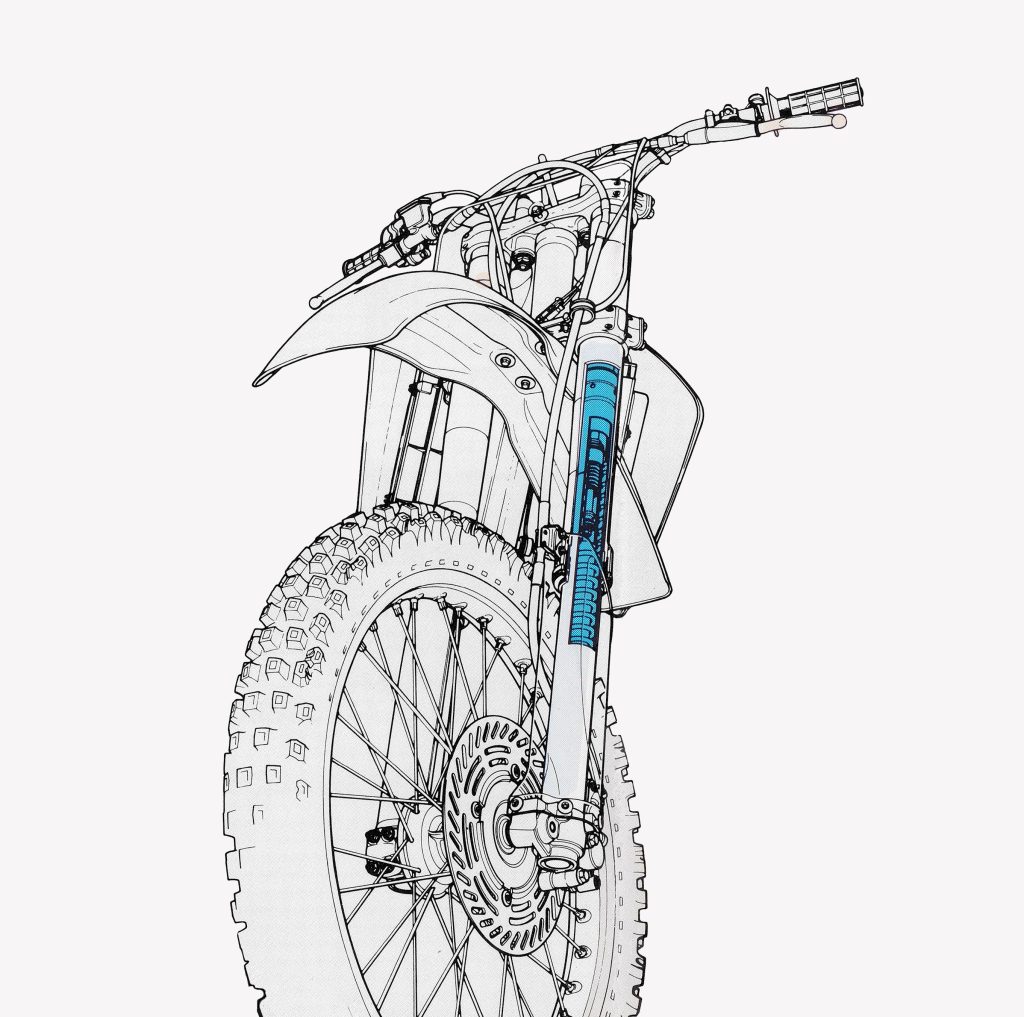

Visually the biggest difference on the CR250R for 1989 was the addition of Showa’s all-new 45mm inverted cartridge fork. By moving the larger diameter area of the fork to the upper clamping area the engineers were able to substantially increase the rigidity of the front end and reduce the protrusion of the fork below the front axle. Photo Credit: Honda

After another class-leading performance in 1987, Honda took a major gamble in 1988. An all-new machine scrapped 90% of the outgoing CR’s design and pointed the way towards a sleeker and more Supercross-focused future. The ’88 CR250R swapped colors to a new “blood red” and introduced a sleek new “low-boy” layout that offered the slimmest and sexist bodywork in the business. The new ergonomics were a unanimous hit but the suspension and motor changes for ’88 proved less popular. Revised settings for the forks ruined their performance and a supercross-oriented linkage for the shock delivered a punishing ride that left most riders cold. While the motor’s design was very similar to 1987, new porting and a tweaking of the Honda Power Port system resulted in a slow-building and mellow delivery that disappointed riders who had become accustomed to the motor supremacy of the previous two seasons.

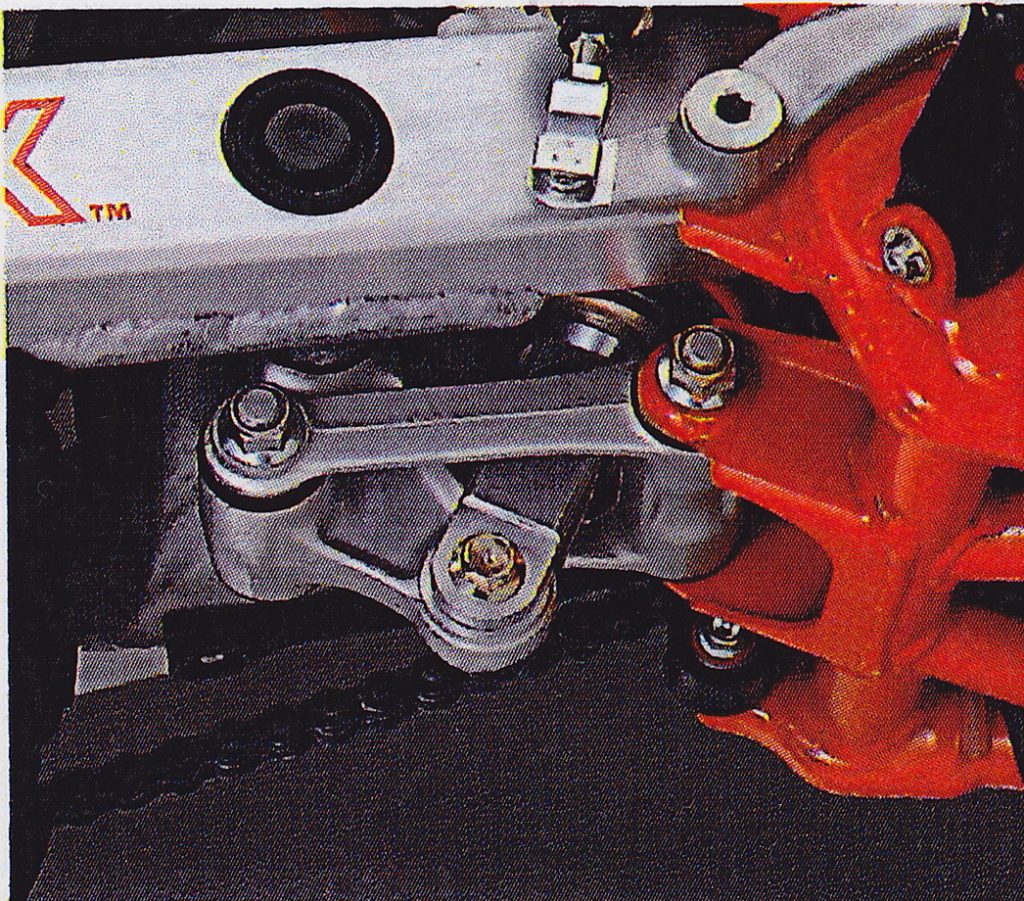

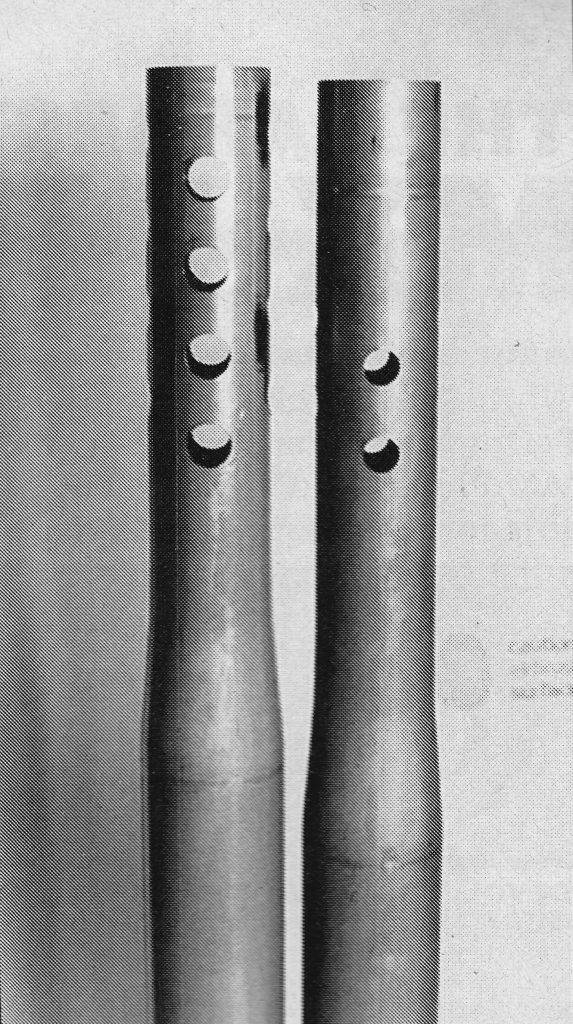

Bent linkage bolts were a common occurrence on the CR250R in 1988 so Honda increased the diameter of all the pivot bolts by 2mm for 1989. Photo Credit: Honda

While the ’88 CR250R proved quite capable on the track, most magazine editors and quite a few consumers found it a disappointing follow-up to the awesome 1987 CR. The slow-feeling motor was competitive, but boring to ride, and the suspension action was a major mis-step after two years of utter fork domination. There were also reliability issues with the ’88 CR’s new “Delta Link” rear suspension that left many racers with bent linkage bolts and aggravating repairs. Overall, it was a machine that pushed the envelope in many ways but failed to back up its sexy looks with class-winning performance.

While the 1989 CRs were far from perfect in performance, their styling was all-time awesome. For my money, this is still one of the best-looking lineups of motocross machines ever produced. Photo Credit: Honda.

In 1988, most of the CR250R’s failings could be traced to setup issues by the engineering and testing staff that led to sub-par results on the track. Decisions to mellow the power and tweak the forks ruined the stock machine’s effectiveness despite its excellent tight track handling and ultra-light feel. For Supercross-style circuits the CR’s chassis was without peer, but its harsh stock suspension and fits of headshake made it a handful outdoors. With some minor motor mods and some suspension work, the 1988 CR250R was an absolute beast, but in stock condition, it was a confused and disappointing machine.

In 1989, all three full-size CRs featured the ’88 250’s sleek new low boy bodywork, but only the 250 and 500 received the trick new inverted forks. While at first this seemed like a slight, most CR125R pilots ended up being thankful for the omission. Photo Credit: Honda

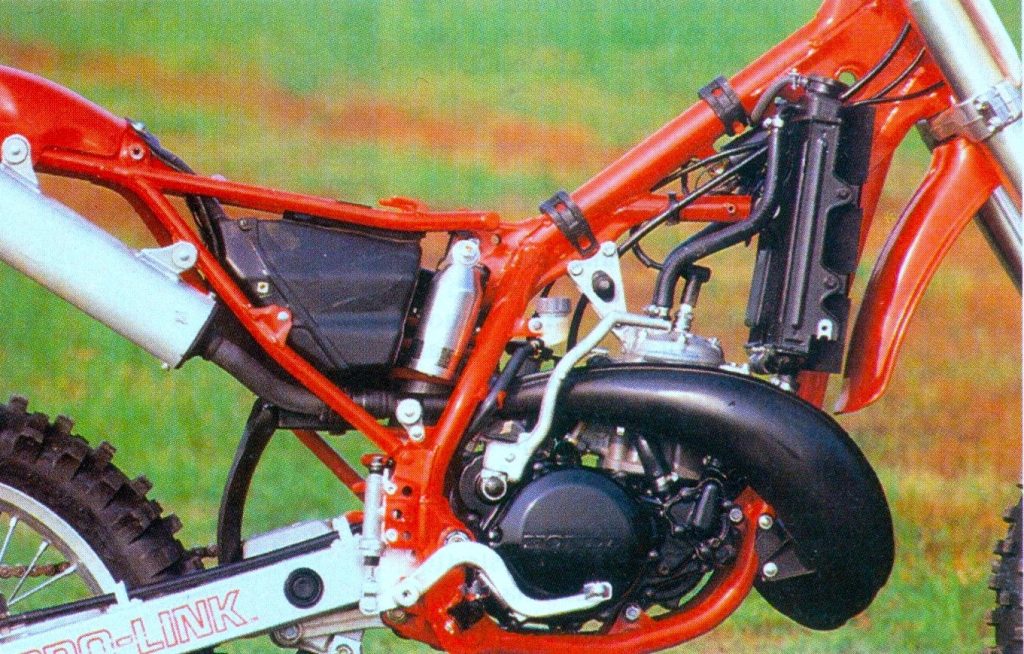

Knowing that the basic DNA of a winner lurked under the ’88 CR’s new bodywork, Honda set out to polish the rough edges off of its Supercross champion package for 1989. First to go was the languid power delivery of 1988. To bring back the bark of 1987, Honda once again reconfigured the porting of its 249cc mill. An all-new cylinder was spec’d that deleted the intake boost ports of ’88, raised the intake ports, and enlarged the exhaust valve. The head was reshaped to lower compression slightly and a new head gasket was employed that was thinner and no longer made of asbestos. To perk up the midrange, the Honda Power Port was re-tuned to open 300 rpm sooner and the reed valve was redesigned to open wider for improved fuel flow. To further perk up the motor’s feel Honda installed a lighter flywheel for ’89 and installed an all-new ignition. In a nod to durability, Honda added a tin plating to the piston pin hole and changed the taper of the pin to be more rigid. As in 1988, the cylinder remained plated in Nikasil for optimal cooling and increased durability.

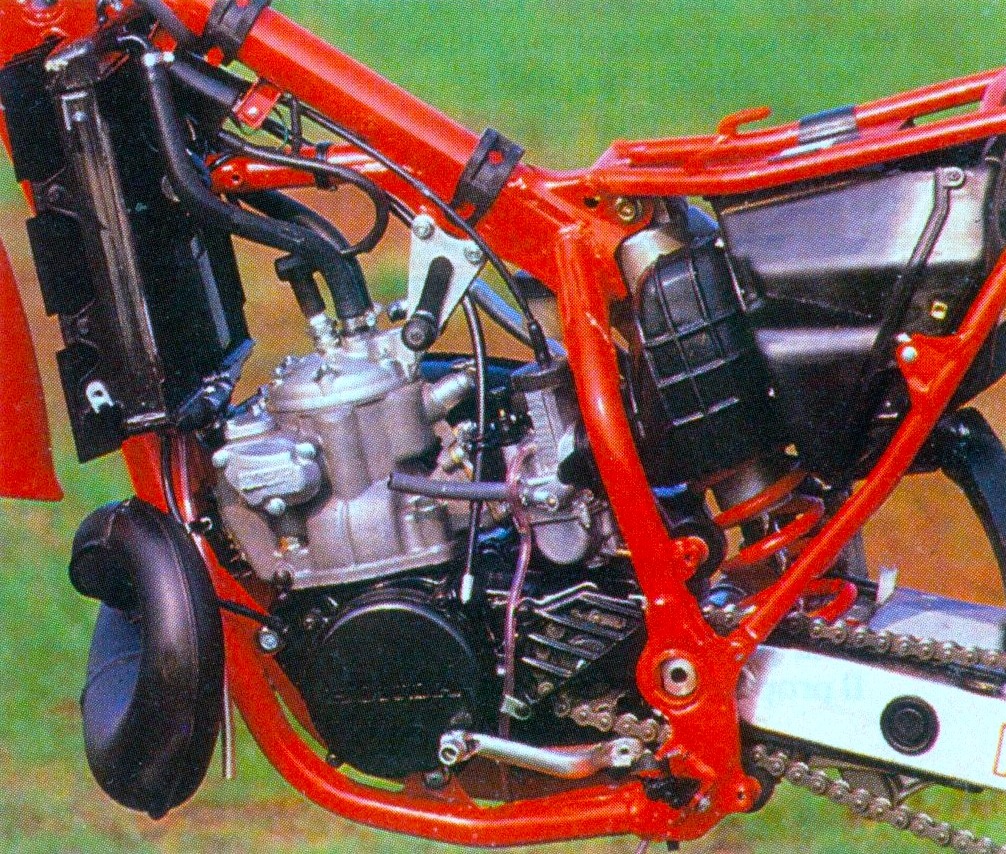

A new frame for 1989 added additional bracing to accommodate the stiffer front end and a slight reduction in trail to improve stability. Photo Credit: Motocross

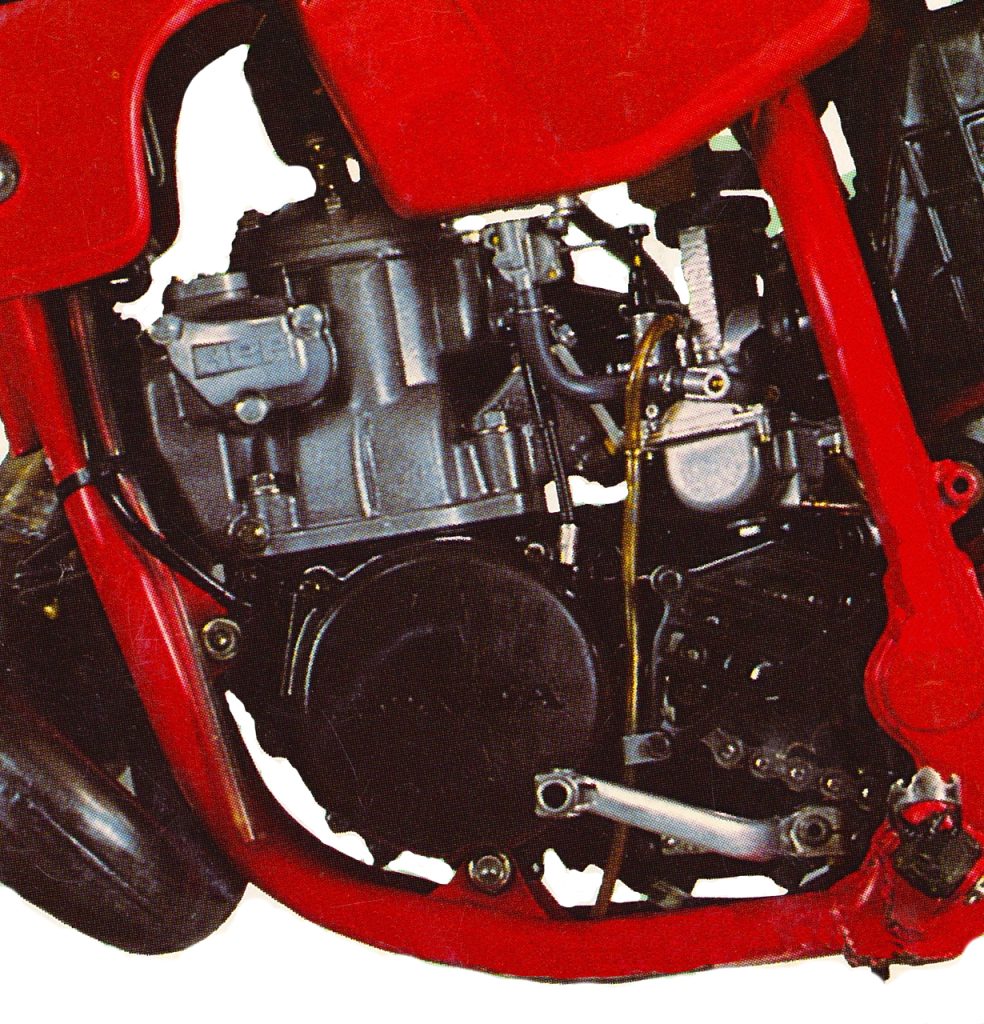

In the bottom end, Honda beefed up the clutch to handle the additional power with stronger springs and new rubber dampers inside the clutch housing. First through fourth gears remained unchanged, but the fifth gear was lowered slightly for 1989. This was done to tighten up the gap between fourth and fifth gear and while this hindered the Honda’s appeal off-road slightly, it was more in line with the CR’s intended purpose as a motocross-first machine.

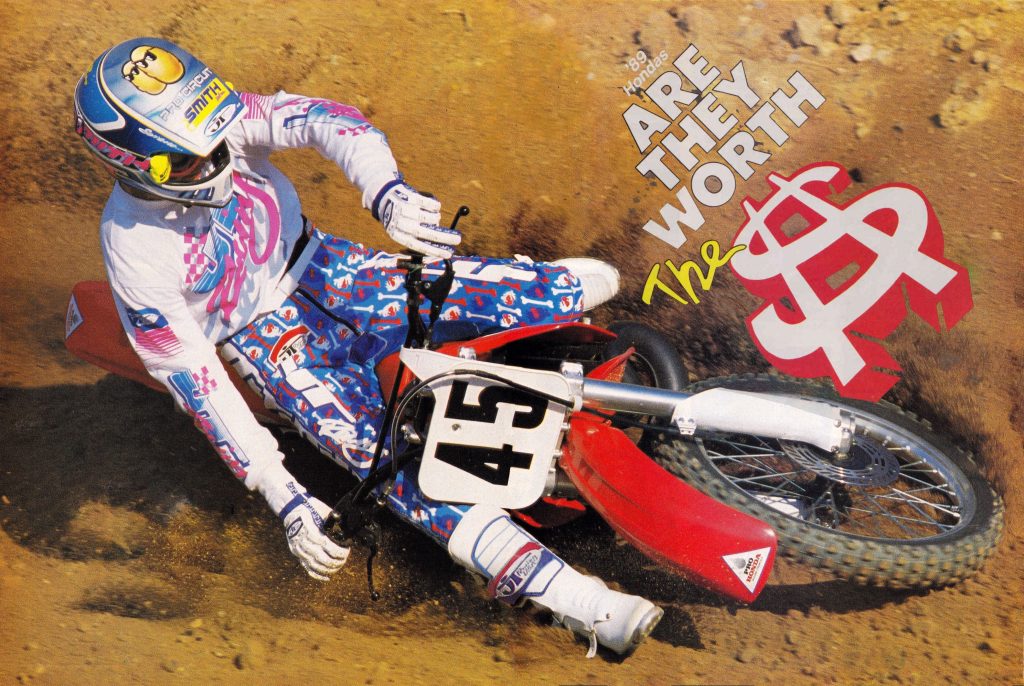

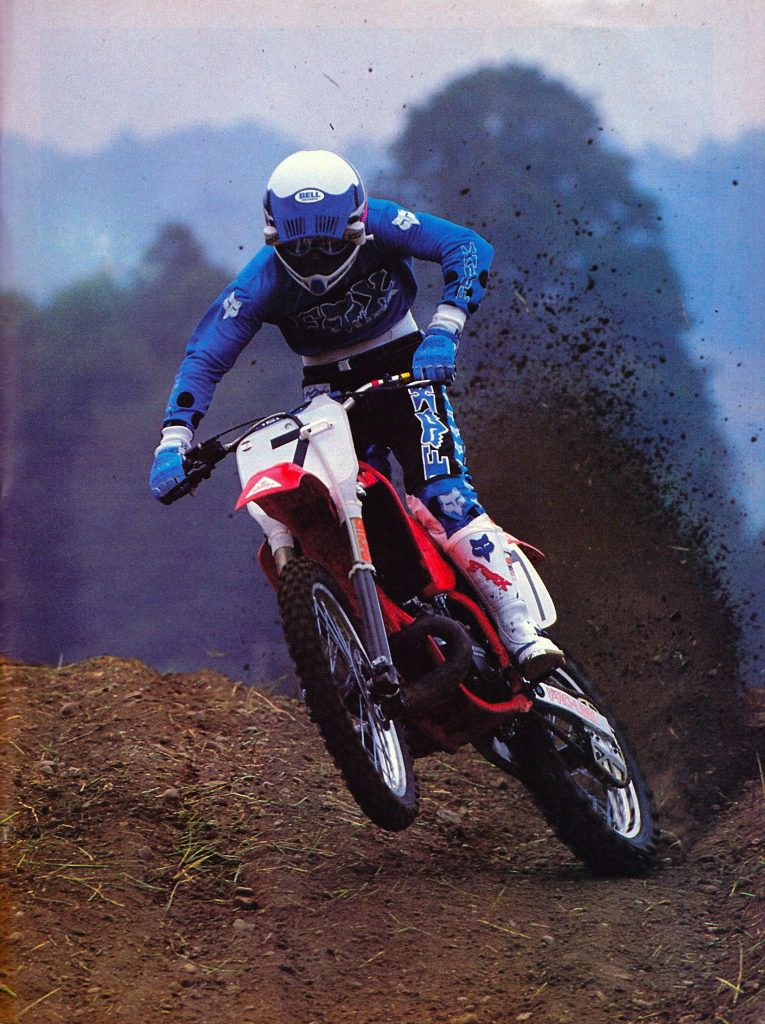

Here Rich Taylor demonstrates the unparalleled turning prowess of the ’89 CR250R. While no one questioned the CR’s handling aplomb, many riders did question the astronomical 30% price hike Honda applied to its motocross machines in 1989. Today, $3998 seems like a bargain, but in 1989 that was a huge sum of money for a 250 class motocross machine. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Of all the changes made on the CR250R for 1989, by far the most dramatic was the adoption of its all-new front suspension system. After sixteen years of conventional forks on its motocross machines, Big Red made the jump to an inverted design in 1989. In use on works machines for several years, the inverted fork offered several advantages over its conventional alternatives. By moving the larger diameter portion of the fork to the clamping area, the inverted or “upside-down” fork offered much greater strength and rigidity. This translated to improved precision in turns, increased stability in the rough, and reduced deflection on hard hits. The inverted design increased fork overlap and decreased fork protrusion below the axle. This further increased rigidity and reduced the chance of catching the front end in a deep rut.

After the disappointing reaction riders had to the ’88 CR250’s long-pulling but mellow delivery, Honda went back to the drawing board for 1989. An all-new cylinder and a major massaging of the HPP system aimed to bring back the bark of 1987. Photo Credit: Motocross

For 1989, Honda moved to an inverted fork on both the CR250R and CR500R with both adopting an all-new 45mm Showa design. This was an increase in diameter of 2mm over the ’88 CR’s conventional sliders. While the forks looked completely different externally, their internal damping system remained very similar to 1988 with 12 inches of overall travel and external adjustments for compression only.

The 250 class of 1989 was a wildly varied one with a lot of solid contenders but no real standout winners. The KX dominated the suspension categories but felt like a truck compared to the Honda and Suzuki. The CR smoked to victory in the motor and turning contests, but shook its head like a wet dog and could not run over a candy bar without pumping your forearms up. The all-new RM was beautiful and fun, but a real handful at speed and prone to blowing up regularly. For off-road, the KTM was a great choice, but most riders felt it was less at home on a motocross track. That left the YZ as the bike that did everything fairly well but nothing poorly. For many riders, that made the YZ the best buy in 1989. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the rear, Honda stayed with the Delta Link Pro-Link design they had introduced in 1988 but made several changes aimed at improving its performance. First up was an increase in diameter for all of the pivot bolts within the linkage. By increasing the diameter by 2mm and improving the quality of the bushings Honda was able to eliminate the embarrassing bending issues it had suffered the year before. The Showa shock was also updated with an all-new compression system that promised a much wider range of adjustment and paired with a lighter spring for smoother action. Aside from the beefed-up pivot points, the Pro-Link design remained unchanged from 1988.

In the right hands the 1989 CR250R was a lethal weapon and Honda’s Rick Johnson put that weapon to good use by sweeping the first five rounds of the ’89 Supercross season. If not for a gruesome wrist injury suffered in practice for the first motocross national, Johnson would almost surely have captured his third AMA Supercross title in 1989. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the chassis front, most of the changes were aimed at improving comfort and increasing durability. Because the new inverted fork transmitted a great deal more force to the frame, Honda’s engineers increased the strength of the steering head and main frame downtube to prevent any stress-related failures. The geometry was also altered slightly to provide a bit less trail to reduce the violent headshake of 1988. To improve rider comfort, the rear subframe was lowered 12mm and the shape of the seat was altered to provide a flatter seating area. The footpegs were also increased in width by 3.5mm to reduce mud buildup and improve rider grip. A new throttle offered a quicker pull and a redesigned brake pedal employed a less aggressive ratio for improved braking feel. Paired with the new lever were redesigned rotors that increased the size of their cooling slots to reduce fading and an all-new rear hub that reduced unsprung weight by nearly a pound. Aside from the reshaped seat and new plastic fork guards, the bodywork remained unchanged for 1989 with the only significant update being a set of bold new graphics.

After a lackluster showing in 1988, the CR250R’s motor made a return to greatness in 1989. Broad, brawny, and blisteringly fast, the CR’s 249cc mill was the model of modern motocross perfection. Chug it, clutch it, or rev it to the moon – regardless of your riding style the CR’s motor had you covered. Photo Credit: Ceet Racing

On the track, the ’89 CR250R turned out to be massively improved in some areas and a bit of a setback in others. The new motor was an absolute rocket that pulled well from just above idle into a chunky midrange and blistering top-end hit. The overall power spread was just as wide as 1988, but with much quicker delivery and stronger midrange hit. Slow guys could lug it out of turns without worrying about it falling off the pipe and fast guys could clutch it on the exit and leave the competition in the dust. Clutch performance, shifting, and ease-of-use were all stellar and the motor received raves from riders of every skill level. About the only complaints were the bike’s overly rich stock jetting and truly annoying habit of fouling plugs. Once you got those issues sorted, you had by far the best 250 motor package of 1989.

Return to sender: While the CR’s motor updates for 1989 proved to be a tremendous success, its suspension changes proved far less well-received. The new 45mm Showa inverted forks were poorly set up from the factory and plagued with particulate contamination issues that fouled their delicate internals. Off the showroom floor, they were too stiff initially, prone to harsh damping spikes in the midstroke, and burdened with a wrist-busting metal-to-metal clank on big hits. Even with a spring swap and revalve, they remained the poorest forks in the 1989 250 division.

Where things went pear-shaped for the CR was once again in the suspension department. Much like 1988, the ’89 CR turned out to be a great handling motorcycle utterly undone by its atrocious suspension. The new 45mm Showa forks certainly looked trick but their performance on the track was nothing short of grim. In stock condition, they were undersprung and overdamped on the compression stroke. Heavy spring preload, harsh damping, and soft spring rates made the forks feel stiff initially before blowing through the stroke on hard hits. There was a nasty spike in the damping mid-stroke and the forks banged to the stops with a metal-to-metal “CLANK” on large jumps. With the ultra-stiff inverted fork, every rock, curb, and clank was transmitted directly to the rider’s wrists and no one aside from Rick Johnson found the new forks to be an improvement.

The outcry from owners displeased with the new fork’s action turned out to be so vociferous that Honda issued a recall mid-year to address their grim performance. While the new internals improved their function slightly, they remained easily the poorest performers in the class. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Amazingly, the fork’s action turned out to be so bad that Honda was forced to release a recall mid-season to improve their woeful performance. Dealers were sent all-new bottoming cones that offered a shorter taper and higher flow to be installed at no additional cost. While this update did improve the compliance of the forks slightly, it did nothing to address the poor stock spring rates and rampant particulate contamination that befouled the Showa’s internals. Even with a swap in springs and updated internals, the forks remained poor performers that were easily at the bottom of the 1989 performance heap.

While the new larger linkage bolts for ’89 fixed the bending issues of 1988, the CR’s Pro-Link rear suspension remained a mediocre performer. Like the forks, the Honda’s shock was too stiff initially and prone to bottoming on big hits. Hammerheads liked its firm feel, but most riders found its harsh action and busy ride tiring. Photo Credit: Honda

In the rear, the picture was slightly better but the CR’s Showa damper remained largely unloved by the majority of testers. The rear of the CR was not as harsh as the front forks, but it required a great deal of aggression to work properly. When ridden aggressively it followed the terrain consistently but if you backed off a bit it became very busy. Slower riders found it too stiff and prone to kicking and the bike could become a real challenge to control at speed in the rough. Like the forks, big air was met with severe bottoming and the Pro-Link remained an odd combination of too hard and too soft. With a spring swap, most riders could live with the stock shock’s action, but only pro-level riders seemed to like its performance. It was a damper set up for aggression and if you were not willing to hammer like Jeff Stanton it was likely to beat you to death in a long moto.

By far the biggest surprise of the 1989 season was the performance of Honda’s newest hire Jeff Stanton. After two years of unremarkable results on his factory Yamaha, the Michigan native moved to HRC Honda and immediately transformed his career. An off-season spent training with Johnson and access to the best machinery in the class resulted in a quantum leap forward in Stanton’s results. Once Johnson exited the series due to his injury, Jeff became the man to beat and piloted the new CR250R to his first AMA 250 National and Supercross titles. Photo Credit: Honda

On the handling front, the CR was once again a bit of a mixed bag. Its turning prowess remained unequaled and the CR could carve over, around, or underneath any other machine on the track. The super-slim layout, low-slung weight, and snappy power made the bike feel 15 pounds lighter than it was and the CR could be thrown around like an ultra-powerful 125. Tight turns and big jumps with short approaches were the Honda’s forte and it was clear the CR was bred to be a Supercross weapon.

Hooked up and under power, the CR250R was nearly unbeatable in 1989. Its fabulous motor, phenomenal turning, flawless brakes, and excellent ergonomics made it an alluring package despite its poor suspension action. It was not a great buy for the “run-it-stock” crowd, but if you made your living racing, it was a hard package to beat. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Outdoors, however, the bike was much less at home. High-speed sections that were drama-free on the YZ or KX were a terrifying thrill-a-minute ride on the CR. The soft forks, stiff shock, and aggressive geometry imbued the CR with an unplanted and busy feel that made the bike highly unpredictable. Despite geometry changes aimed at increasing the machine’s stability, the front end continued to shake violently when coming down from speed. Lock-to-lock swaps were not uncommon, and the CR was easily the worst machine for off-road use in stock condition. Once the suspension was sorted, the machine became much more manageable, but its Supercross-first personality was always apparent.

A super-slim layout and snappy power made the CR one of the best leapers in the class in 1989. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

In the detailing department, the CR250R was an improvement in some areas and a step back in others. The new beefed-up linkage did away with the bent bolts of 1988 and proved trouble-free as long as the bearings were greased regularly. A new aluminum side cover also solved the annoying water-pump corrosion issues suffered on previous CRs which employed magnesium for their side case material. A revised air filter for 1989 offered improved sealing but suspect longevity. Four to five cleanings were about all you could expect to get out of it before the glue started to give up the ghost. Going to a Twin Air or Uni filter was cheap insurance on your $3998 investment. Speaking of price, it was hard not to note the astronomical $900 price increase Honda tacked onto the CR250R in 1989. That was a jump of almost 30% year-over-year and nearly $2000 in today’s money. Honda claimed most of that was due to an unfavorable exchange rate with the Yen but even with that taken into account it was still the most expensive machine in the class. If you bought a KX250 in 1989, you would have way better suspension and still have another $400 left over for mods.

Holeshots were the CR250R’s stock-in-trade in 1989. Photo Credit: Mark Kariya

At least for all that money, you got a well-put-together motorcycle. The quality of everything from the brakes, to the bolts, to the bodywork, was best in class. Long after a Suzuki or Kawasaki felt beat, the CR looked and felt fresh. The motor proved largely bulletproof with only the occasional fouled plug or notched clutch basket marring its stellar reliability record. While the motor was reliable, its need for regular HPP maintenance continued to be a real pain in the kidney belt. If you ignored this complicated and time-consuming task, then sticky valves eventually sapped the snap out of the CR’s mill. The new forks also demanded constant attention due to the absurd amount of particulate contamination their internals sloughed off into the damper fluid. Draining the oil every three to four rides was the only way to prevent their action from transitioning from grim to Medieval. Lastly, care had to be taken with the new forks not to overtighten the pinch bolts in the clamps. Unlike conventional forks, where this was not a concern, the new inverted fork’s performance could be affected by overtightening the clamps.

In 1989 the CR250R was a highly capable but flawed motocross package. With its aggressive handling, rocket motor, and bullet-proof reputation it made an excellent pro-level race bike, but its utter lack of suspension finesse and sky-high retail price made it a harder sell to the unwashed masses. Photo Credit: Honda

Overall, the 1989 Honda CR250R turned out to be a flawed but highly effective motocross weapon. Blessed with razor-sharp handling, legendary reliability, and the fastest motor in the class, it was only a fork away from absolute domination. For riders who made a living twisting their right wrist, its additional cost and flummoxing forks were a small price to pay to gain access to its other virtues. If you were more of the buy-it and ride-it-stock crowd, however, there were probably better racing choices in 1989.