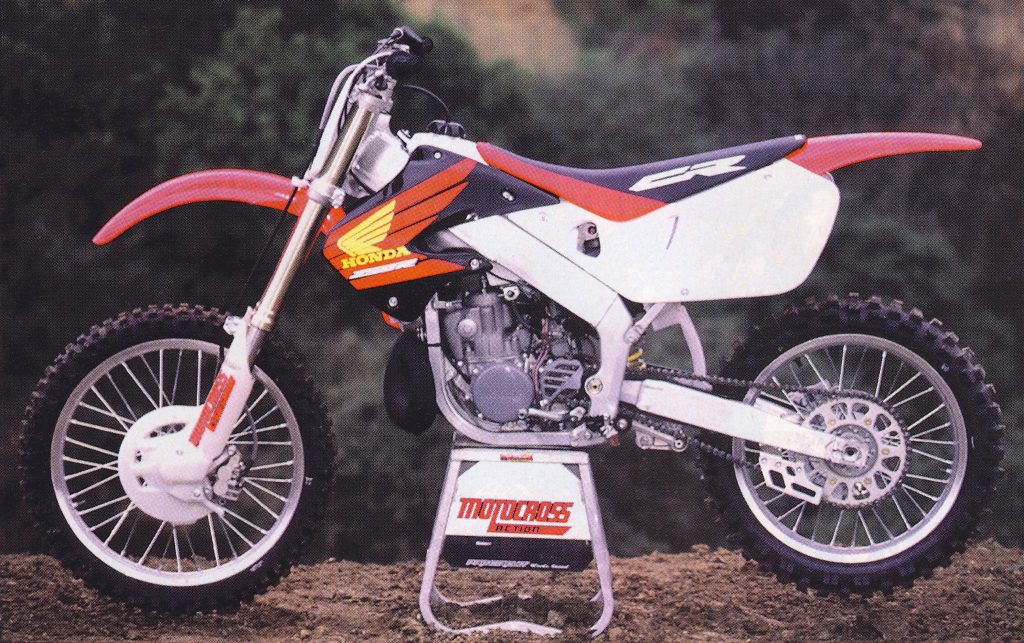

For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to look back at year two of Honda’s aluminum chassis experiment with the 1998 CR250R.

In 1998, Honda introduced the second year of its aluminum motocross experiment. Like the 1997 version, the ’98 CR250R offered tons of power and a chassis in need of some additional refinement. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1998, Honda introduced the second year of its aluminum motocross experiment. Like the 1997 version, the ’98 CR250R offered tons of power and a chassis in need of some additional refinement. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1997, Honda kicked off the start of the aluminum motocross chassis movement with the introduction of its groundbreaking all-new CR250R. Today, it is hard to overstate the amount of excitement and anticipation surrounding the introduction of Honda’s alloy-framed wonder. At the time, Honda was on an incredible win streak with their CR250R dominating the professional race standings for more than a decade. Factory riders Rick Johnson, Jeff Stanton, Jean-Michel Bayle, and Jeremy McGrath took Honda’s 250s to victory in every Supercross title from 1988 through 1996 with several outdoor titles as well going to the red machines. This era of domination made them the bikes to own in the minds of many, despite some glaring inadequacies on the suspension front.

In 1997, the introduction of Honda’s alloy-framed CR250R was one of the biggest news stories in the sport. Beautiful, controversial, and in many people’s minds, the reason for Jeremy McGrath’s departure from the brand, the all-new CR250R proved to be a huge hit in the showroom despite its polarizing nature on the track. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1997, the introduction of Honda’s alloy-framed CR250R was one of the biggest news stories in the sport. Beautiful, controversial, and in many people’s minds, the reason for Jeremy McGrath’s departure from the brand, the all-new CR250R proved to be a huge hit in the showroom despite its polarizing nature on the track. Photo Credit: Honda

Initially, the reviews for Honda’s new aluminum framed machine were glowing. Magazine editors loved its spacy looks and praised its stout chassis and rocket-fast motor. Early reviews had many pit pundits thinking Honda had hit a home run with their new machine, but those opinions began to shift once testers and consumers spent a bit more time on the machine. Early praise for its “pro-ready” chassis turned to grumbles over its lack of compliance and harsh suspension performance. The motor and looks remained standout, but the harsh chassis, concrete seat, incessant vibration, and disappointing suspension made the ’97 CR250R a bike easy to fall for but hard to live with.

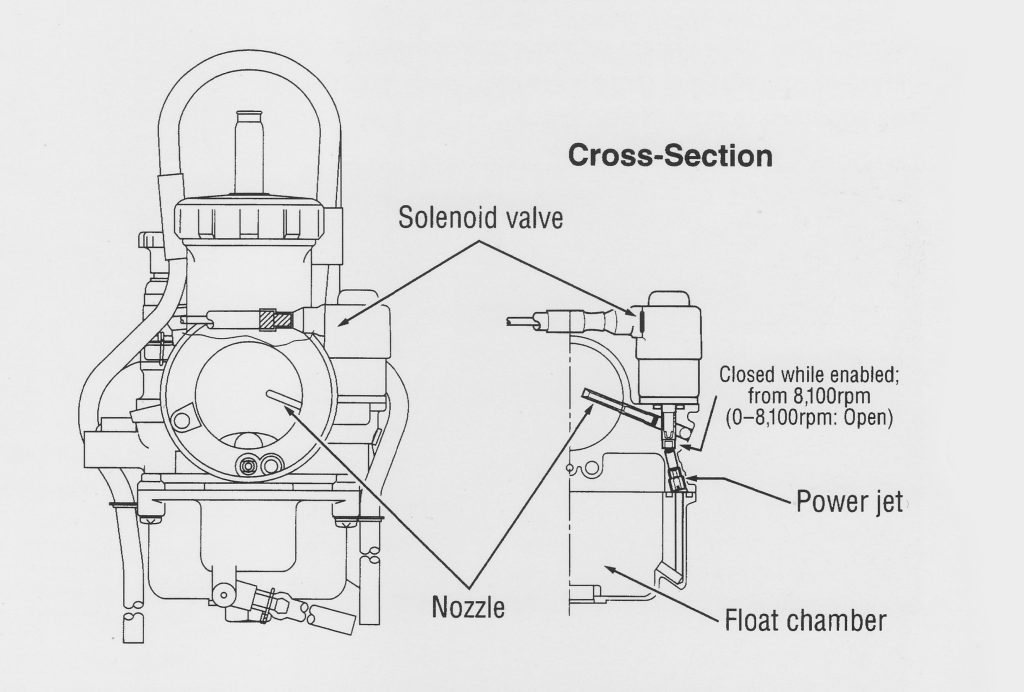

In 1997, Honda added Keihin’s latest innovation – the “PowerJet” – to the carburetor on the CR250R. The theory behind the PowerJet was to provide additional fuel at lower rpm for improved throttle response without overly enriching the fuel mixture at high rpm. An electric solenoid mounted to the carburetor controlled the secondary fuel circuit and opened and closed the valve as needed to optimize fuel delivery. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1997, Honda added Keihin’s latest innovation – the “PowerJet” – to the carburetor on the CR250R. The theory behind the PowerJet was to provide additional fuel at lower rpm for improved throttle response without overly enriching the fuel mixture at high rpm. An electric solenoid mounted to the carburetor controlled the secondary fuel circuit and opened and closed the valve as needed to optimize fuel delivery. Photo Credit: Honda

For Honda, most of the complaints levied at the all-new CR could be traced back to decisions made in the pursuit of chassis reliability. While aluminum frames had been in use on street machines for over a decade, no other major manufacturer had attempted to bring them to the off-road world. The unique demands of off-road use presented several challenges to Honda’s engineers, and it was felt that preventing a high-profile failure was more important than providing the new CR250R with the old bike’s more compliant feel. This decision led Honda to err on the side of durability and beef up the ’97 CR’s chassis to the point where it adversely affected its handling. On the reliability front, this approach worked with the new alloy chassis proving to be extremely rugged. Frame failures were rare, and Honda proved that aluminum could be used for motocross frame construction without any significant penalties in reliability. Where the picture became less clear was on the performance front. The ultra-stiff character that made aluminum perfect for road-racing applications proved less advantageous off-road. The ’97 CR250R’s chassis transmitted every rock, bump, and hump directly to the rider’s hands and backside and made the machine extremely tiring to ride.

An all-new frame for 1998 maintained the 1997’s twin-spar design but reconfigured the geometry and added in some additional flex to improve cornering and comfort. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new frame for 1998 maintained the 1997’s twin-spar design but reconfigured the geometry and added in some additional flex to improve cornering and comfort. Photo Credit: Honda

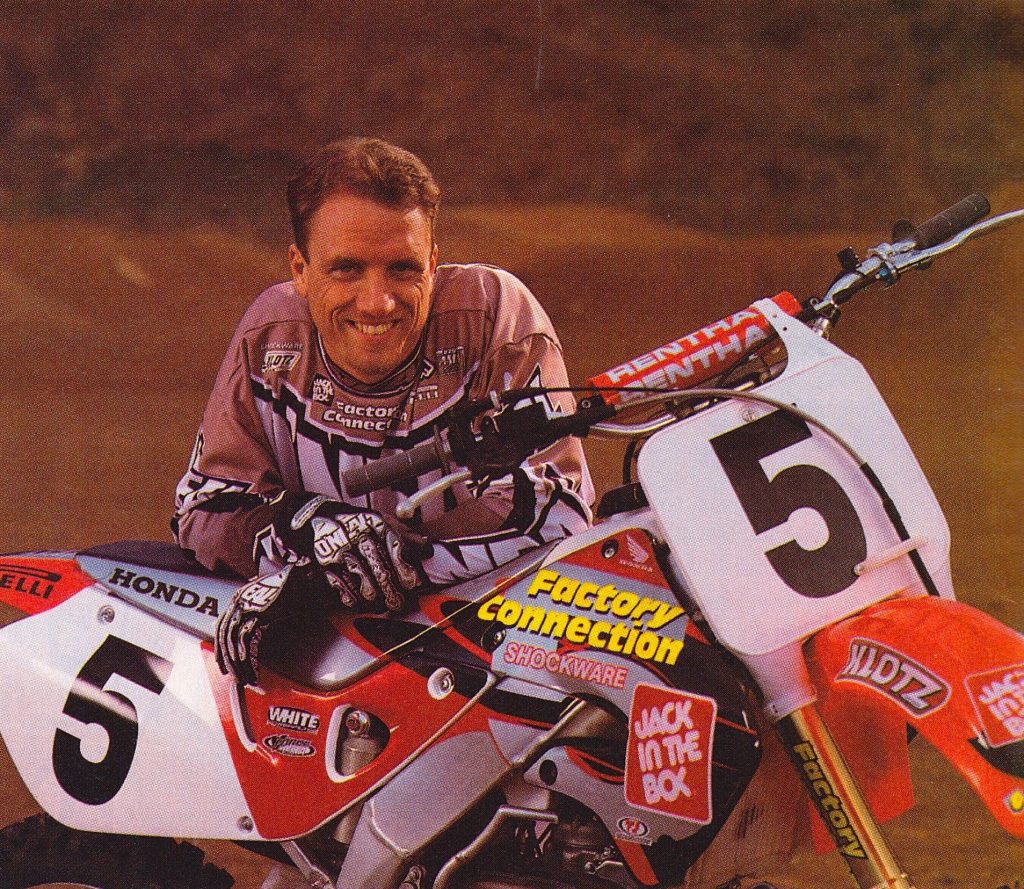

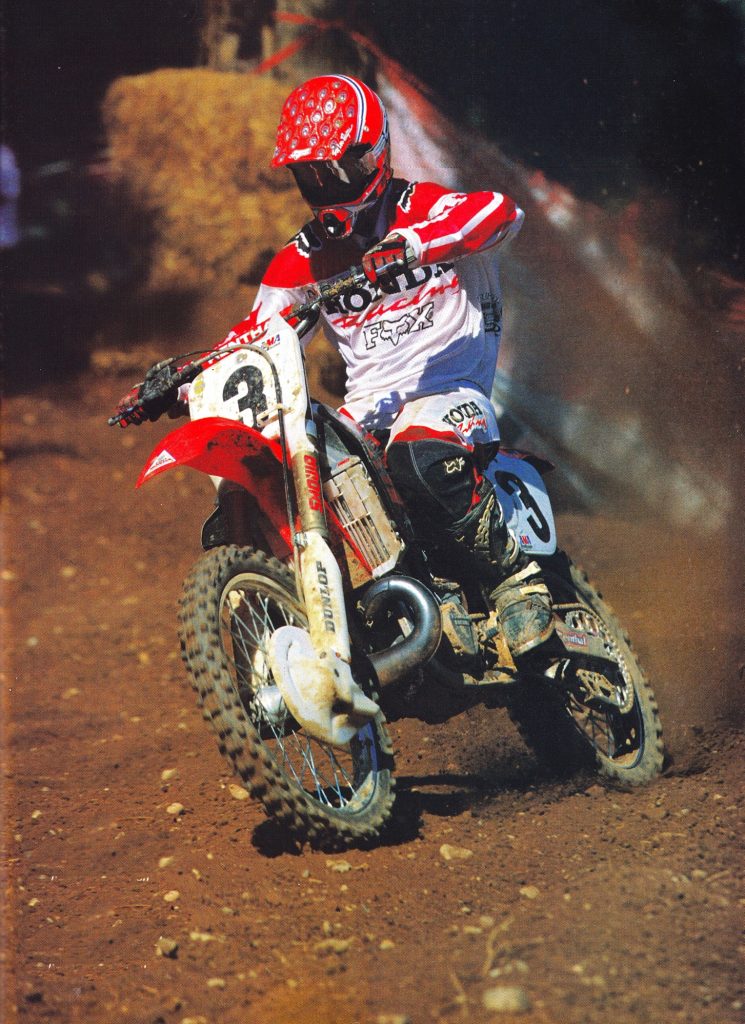

After a tumultuous two years at Suzuki, two-time National Motocross champion Mike LaRocco made the move to Honda in 1998. His hard-charging style proved a good fit with the red machine, and he would take his Jack In The Box backed CR to 3rd overall in the 1998 250 National Motocross standings. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

After a tumultuous two years at Suzuki, two-time National Motocross champion Mike LaRocco made the move to Honda in 1998. His hard-charging style proved a good fit with the red machine, and he would take his Jack In The Box backed CR to 3rd overall in the 1998 250 National Motocross standings. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

While the reviews for the new ’97 CR250R turned out to be quite mixed, its popularity in the showrooms was unquestionable. Riders snapped up the alloy-framed CRs in droves largely based on hype and Honda’s reputation for winning. Bold in design, beautiful to look at, and impeccably built, the 1997 CR250R was not the bike many had hoped it would be, but it did prove that aluminum could be a viable choice for motocross chassis design.

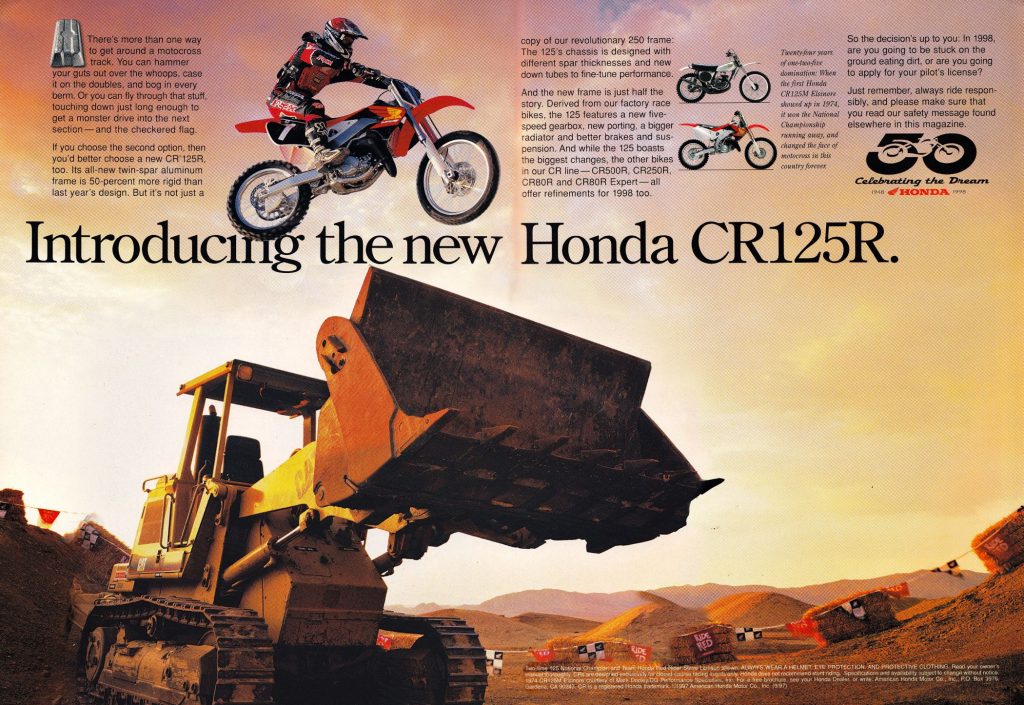

Honda’s CR125R adopted the 1997 250’s alloy frame design in 1998.

Honda’s CR125R adopted the 1997 250’s alloy frame design in 1998.

In 1998, Honda’s focus shifted to the 125 division with an all-new CR125R. The redesigned tiddler featured a version of the 250’s alloy chassis and a revamped five-speed motor. Long the powerhouse of the 125 division, the hype for the all-new red 125 was only slightly tamped down by the trepidation some felt about the move to aluminum.

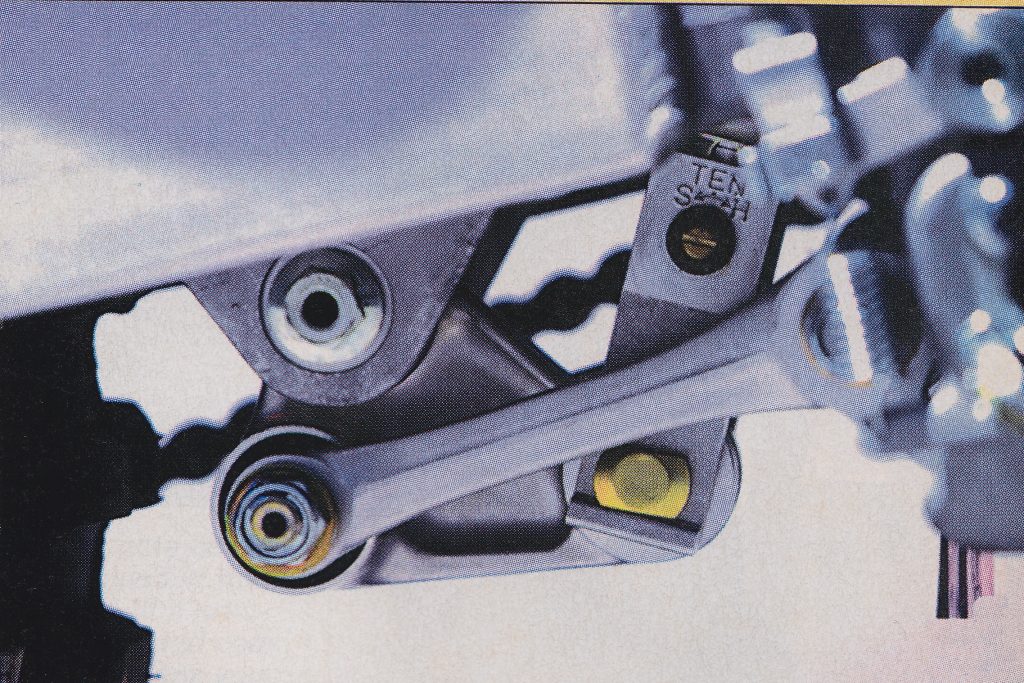

An all-new linkage for 1998 looked to address some of the complaints riders had voiced with the 1997 machine by offering a flatter curve that would prevent the shock from squatting excessively under acceleration. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new linkage for 1998 looked to address some of the complaints riders had voiced with the 1997 machine by offering a flatter curve that would prevent the shock from squatting excessively under acceleration. Photo Credit: Honda

On the 250 front, the R&D department’s focus on the 125 meant a season of minor refinements for the CR250R. Long the gold standard of deuce-and-a-half performance, the CR’s 249cc power plant carried over largely unchanged from 1997. In use since 1992, Honda’s CRV (Composite Racing Valve) design was famous for its long pull and blistering midrange performance. For 1998, Honda revamped jetting on the 38mm Keihin PowerJet carburetor, added a new stainless steel clutch cable (for improved durability), and repositioned the countershaft sprocket to better align with the drive sprocket in the rear. Aside from these minor changes the CR’s motor was identical to the year before.

After a very disappointing 1997 season, Honda made a major move to upgrade its 250 program in 1998 by hiring Ezra Lusk away from Yamaha. Lusk would make an immediate impact, taking home four wins on his way to second in the 1998 Supercross series.

After a very disappointing 1997 season, Honda made a major move to upgrade its 250 program in 1998 by hiring Ezra Lusk away from Yamaha. Lusk would make an immediate impact, taking home four wins on his way to second in the 1998 Supercross series.

For 1998, Honda’s main focus was improving the handling and suspension feel of the CR250R. The new frame had proved durable and the bike was well suited for hard chargers, but most riders below the pro class found the machine’s harsh character off-putting. The new frame also exhibited a vagueness in the front end that was foreign to most riders accustomed to Honda’s traditional turning prowess. With that in mind, Honda made a few significant changes aimed at improving the CR’s handling and reducing its harsh feel.

All-new forks for 1998 extended travel but did very little to turn around Honda’s reputation for poor suspension performance. Softer settings for 1998 aimed at improving comfort ended up doing the opposite as the forks drooped, banged, and blew through their travel. Photo Credit: Honda

All-new forks for 1998 extended travel but did very little to turn around Honda’s reputation for poor suspension performance. Softer settings for 1998 aimed at improving comfort ended up doing the opposite as the forks drooped, banged, and blew through their travel. Photo Credit: Honda

First up was an all-new Showa Twin-Chamber fork for the front end. This new fork increased travel by 9mm and added a plethora of friction-reducing tricks to reduce stiction and improve its action. The springs were polished to reduce friction and the interior tubes were subjected to a liquid honing process to insure they moved freely. A molybdenum coating was added to the inner surface of the outer tubes to reduce binding and further free up the fork’s movement. A new cartridge design featured a freer-flowing piston and reduced binding by allowing the spring to rotate within the fork as it was compressed. New settings reduced compression damping and a lighter spring was added to provide a smoother ride.

By far the best part of the 1998 CR250R’s motocross package was its 249cc powerhouse of an engine. In use since 1992, this power plant was the gold standard of performance in the 250 class for nearly a decade. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

By far the best part of the 1998 CR250R’s motocross package was its 249cc powerhouse of an engine. In use since 1992, this power plant was the gold standard of performance in the 250 class for nearly a decade. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the rear, an all-new shock was added that once again increased travel slightly. The new Showa damper was 14.5mm longer and featured 5.8mm more shock travel than in 1997. Paired with the new shock was a redesigned linkage that featured a flatter curve for ‘98. The new linkage was designed to be slightly stiffer initially and more compliant as the shock reached the end of its travel. This combined with lighter damping settings and a softer spring was designed to bring back some plushness to the CR’s rear suspension.

The Fifth Dragon: Honda had quite a presence in the 250 class in 1998 with Larocco’s Factory Connection team and Phil Alderton’s Honda of Troy squad riding under the red banner. Photo Credit: N-Style

In addition to the new suspension, Honda revamped the CR’s chassis quite extensively. The frame remained crafted out of 7000-series aluminum in a twin-spar configuration, but the geometry was all-new for 1998. The new chassis featured a steeper caster, shorter trail, and reduced wheelbase to improve turning. The new frame also enlarged the lightening holes in the steering gusset by 4mm and revised some of the welding methods to bring back a little bit of flex to the chassis. A new subframe used thinner-walled tubing and a new seat featured softer foam to increase rider comfort in the rear. The swingarm was redesigned to work with the revised frame and linkage and featured a 1.5 mm thicker cross brace to prevent twisting under heavy loads. Aside from the softer seat foam and new graphics, the CR’s bodywork remained unchanged from 1997. The wheels, brakes, and controls were all carryovers as well with the CR continuing to offer the finest fit and finish in the class.

In 1998, only Kawasaki’s excellent low-to-mid powerhouse of a motor had a shot at unseating the CR as the King of 250 performance. The KX offered more torque down low and a comparable midrange, but the CR blew its doors off once the RPM climbed past 8500. While many riders preferred the KX’s grunt to the CR’s revs, there was no denying that both were incredibly effective on the track. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1998, only Kawasaki’s excellent low-to-mid powerhouse of a motor had a shot at unseating the CR as the King of 250 performance. The KX offered more torque down low and a comparable midrange, but the CR blew its doors off once the RPM climbed past 8500. While many riders preferred the KX’s grunt to the CR’s revs, there was no denying that both were incredibly effective on the track. Photo Credit: Honda

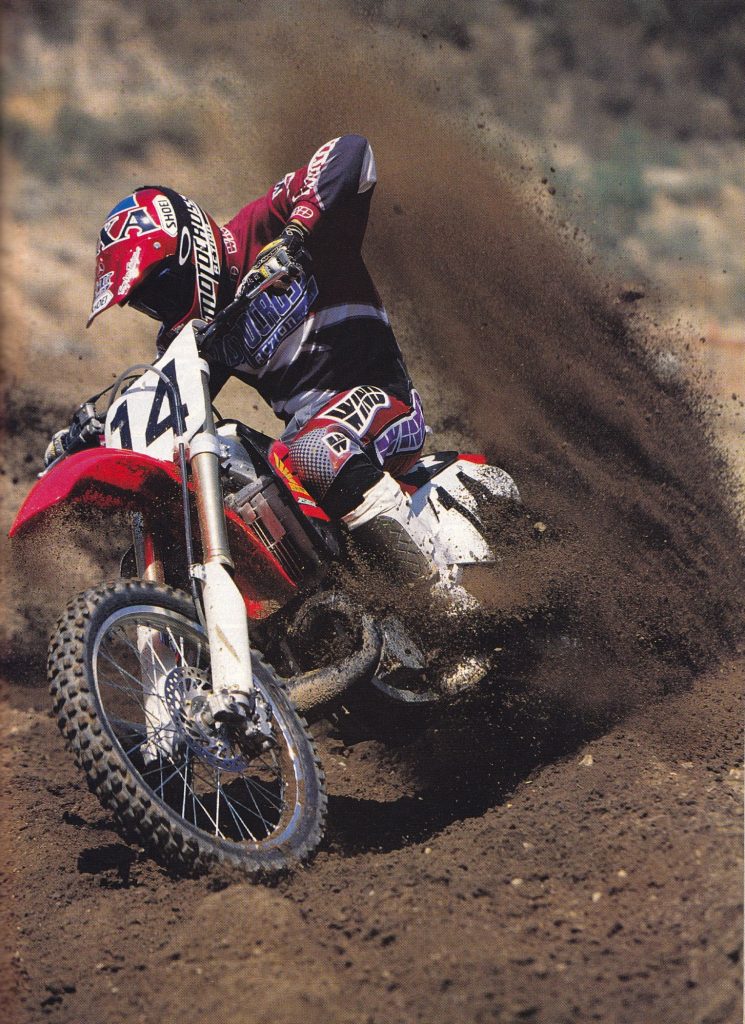

Workout machine: While the CR250R offered more than enough power to pull you to the front in ‘98, its chassis and suspension made using that power difficult. Imprecise handling, excessive vibration, and pummeling suspension conspired to make the CR the most tiring machine to ride in the 250 division. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Workout machine: While the CR250R offered more than enough power to pull you to the front in ‘98, its chassis and suspension made using that power difficult. Imprecise handling, excessive vibration, and pummeling suspension conspired to make the CR the most tiring machine to ride in the 250 division. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the track, the 1998 CR250R remained a wickedly fast but flawed machine. As in 1997, its motor was its greatest asset with novices and pros alike praising its awesome output and endless pull. Down low, there was not a lot going on, but once the CR hit the midrange it was all fire and brimstone until the rider backed off or the CR was at the front. Some riders preferred the Kawasaki KX’s beefy low-end blast to the Honda’s shrieking top-end pull but both were brutally effective on the track. On slick surfaces, the CR’s hard hit and lack of torque could be a hindrance, but as long as there was traction, the CR was the fastest gun in the West. When combined with its flawless shifting, bulletproof clutch, and unimpeachable record for reliability, the CR had what many considered to be the perfect 250 power package in 1998.

An all-new shock and linkage did not do much to take the “thud” out of the CR’s rear suspension for ‘98. Like the forks, its settings were too soft and underdamped for serious motocross use and most riders felt it was worse than the year before. It squatted under acceleration, pitched forward under braking, and danced around like a cat on a hot tin roof in the rough. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new shock and linkage did not do much to take the “thud” out of the CR’s rear suspension for ‘98. Like the forks, its settings were too soft and underdamped for serious motocross use and most riders felt it was worse than the year before. It squatted under acceleration, pitched forward under braking, and danced around like a cat on a hot tin roof in the rough. Photo Credit: Honda

Where things once again went pear-shaped for the Honda was in the chassis department. The frame and suspension changes aimed at softening its personality did not turn out to be particularly effective. The chassis remained very sensitive to track conditions and proved the most finicky of the Big Five to set up. Settings that worked at one track felt completely wrong at another and the Honda pilot was left chasing sag and suspension settings far more than on the other machines in the class. If you did get the setup right the Honda was a decent handler, but its days as the carving knife of moto were in the past. In slow corners the front end exhibited a push, and at speed, it was still a bit of a shaker. No one declared it an absolute roach, but it was far from the best handler in the class.

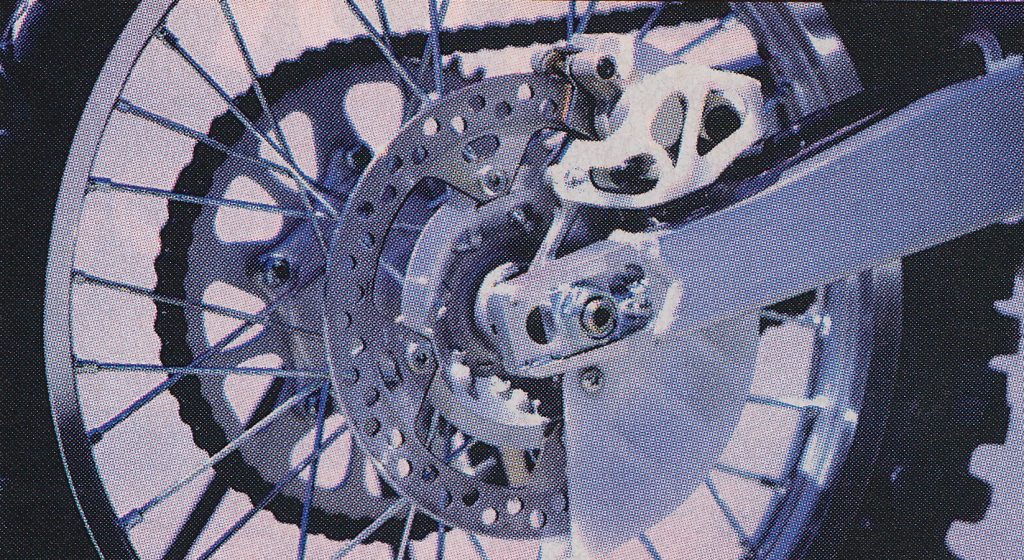

Honda’s reputation for flawless brakes and top-quality components continued in 1998. Photo Credit: Honda

Honda’s reputation for flawless brakes and top-quality components continued in 1998. Photo Credit: Honda

Some of this chassis imprecision had to do with the CR’s suspension, which continued to disappoint despite its many upgrades for 1998. The new fork settings were too soft initially which caused them to dive under braking and hang down in their travel. This upset the chassis balance and caused the front end to feel harsh as it moved too quickly into the heavier part of its damping curve. There was notably less stiction than in the past and the fork exhibited less of the harshness Honda had become famous for, but on hard hits, it blew through its travel and left many wanting stiffer springs at a minimum. Pros were particularly unhappy with the stock settings but even novices felt that Honda had gone too far in the pursuit of more compliance. With some stiffer springs and a bit of oil fiddling the forks could be made passable but even with these upgrades, the CR’s legs were some of the least popular in the class.

The harsh frame and poorly set up suspension made the stock CR a mediocre handler at best. There was still a fair amount of headshake and the chassis was very difficult to get properly balanced. Once the suspension was sorted the Honda was certainly raceable, but riders were never going to mistake it for the corner-carving scalpel the CR had been in the early nineties. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The harsh frame and poorly set up suspension made the stock CR a mediocre handler at best. There was still a fair amount of headshake and the chassis was very difficult to get properly balanced. Once the suspension was sorted the Honda was certainly raceable, but riders were never going to mistake it for the corner-carving scalpel the CR had been in the early nineties. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Out back, the story was much the same with the new settings delivering an overly soft and uncontrolled ride. The shock’s light damping caused it to move excessively in turns and upset the chassis balance. The shock extended too much under braking and squatted abruptly under acceleration. If you tried to dial up more damping to get the movement under control, then the shock became harsh. The alloy chassis imparted a “dead” feel to the rear end and the CR thudded into obstacles that machines like the KX floated over. Even lighter and slower riders commented on the Honda’s sub-par shock action and nearly everyone felt the CR needed stiffer springs and a revalve to be competitive. If you were slow and under 150 pounds, then the stock suspension was raceable, but for everyone else, both ends were going to need some serious work.

Lusk’s ’98 outdoor season was less successful than his indoor campaign, with a single victory at High Point being the highlight of his motocross season. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the detailing front, the Honda remained the class of the field in 1998. The bodywork fit perfectly, wore well, and looked great aside from the ugly gray smears the aluminum frame transferred to the side panels. The alloy frame also looked new far longer than the painted steel competition. The brakes worked flawlessly and delivered the most bite and best feel in the class. The stock steel bars were remarkably tough and stronger than many aftermarket aluminum alternatives. Likewise, the Honda’s forged levers were of higher quality than the cast components found on many other brands and could withstand a great deal of abuse without snapping or failing. The grips were also quite comfortable, and many people did not feel the need to replace them until they were damaged or worn out. While the clutch lever’s shape was quite comfortable as well, its pull left some riders looking for a hand exerciser. It was far heavier than the ultra-light Suzuki’s, but its durability was without a peer. As long as you kept the fluid fresh, the Honda’s clutch and transmission were the most durable in the class.

In 1998, the Kawasaki KX250 was the best machine available in the 250 class. It lacked the Honda’s top-end pull and impeccable build quality, but it made up for it with a mauler of a low-to-mid motor and much better suspension. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1998, the Kawasaki KX250 was the best machine available in the 250 class. It lacked the Honda’s top-end pull and impeccable build quality, but it made up for it with a mauler of a low-to-mid motor and much better suspension. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the not-great side of the ledger were the CR’s annoying vibration, hefty feel, and lack of overall comfort. Vibration through the chassis was a constant annoyance and the new softer seat was still closer to a block of concrete than a Lazy-Z-Boy. The wide frame and unique chassis feel also made the bike feel bigger and heavier than the scale would indicate. Despite being the lightest bike in the class and undercutting some competitors by as much as ten pounds, the CR felt like one of the heaviest. This was not easily addressed, but at least an aftermarket seat and a switch to the CR500’s rubber-mounted top clamp could do a lot to reduce the tingle and improve backside comfort.

After a season of hype-induced hysteria, Honda’s CR250R came crashing back to Earth in 1998. For most riders, its endless pull and spacy looks were not enough to offset its harsh chassis, heavy feel, and clunky suspension. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

After a season of hype-induced hysteria, Honda’s CR250R came crashing back to Earth in 1998. For most riders, its endless pull and spacy looks were not enough to offset its harsh chassis, heavy feel, and clunky suspension. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Overall, the 1998 Honda CR250R proved to be a disappointment in many respects. It still offered the Motor of Doom, but its alloy chassis and revamped suspension were still a work in progress. No other bike on the track was as fast, well built, or cutting edge, but that edge cut both ways. The alloy chassis that captured rider’s imaginations the year before was still a bit too big, bulky, and overbuilt, and Honda’s efforts at toning down that harshness with softer suspension settings turned out to backfire. The bike could certainly win in the right hands, but for most riders, the 1998 CR250R was a bit too far out on the bleeding edge to be the perfect motocross weapon.

For your daily dose of motocross goodness make sure to give me a follow @tonyblazier on Instagram and Twitter