For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to look back at Kawasaki’s all-new “Works Replica” KX250 for 1985.

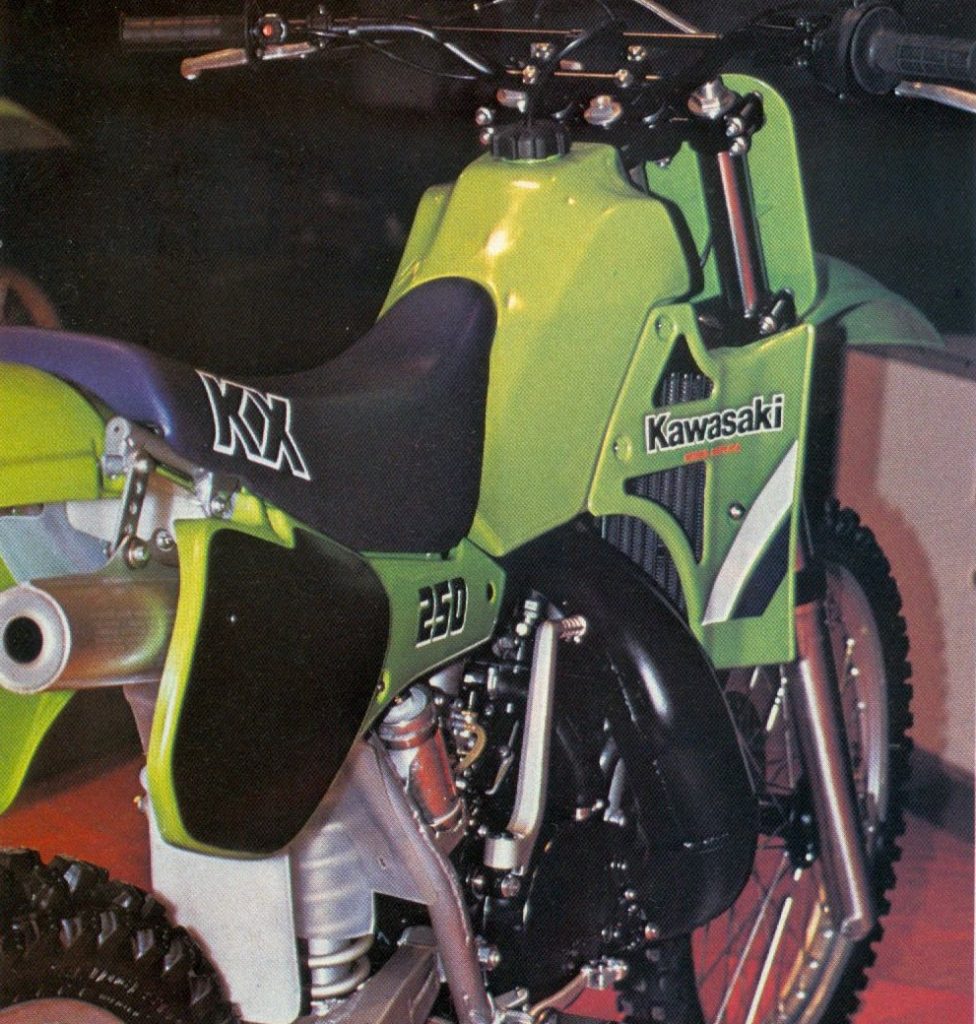

All-new for 1985, Kawasaki’s redesigned KX250 was packed with innovations and style. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

All-new for 1985, Kawasaki’s redesigned KX250 was packed with innovations and style. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The early 80s were a tough time to be riding green in the big bike classes. While Kawasaki had finally cracked the code for success in the small-bore divisions, they had continued to struggle with the larger machines. In this era, the KX250 and KX500 were remarkable more for their oddball styling and problematic reliability than their performance on the track. Cracked frames, broken hubs, leaking exhausts, and brittle plastic were all part of the KX ownership experience during this time. On the KX60, KX80, and KX125, these reliability bugaboos were offset by class-leading performance, but in the 250 and 500 class, Kawasaki’s motocrossers struggled to garner much affection.

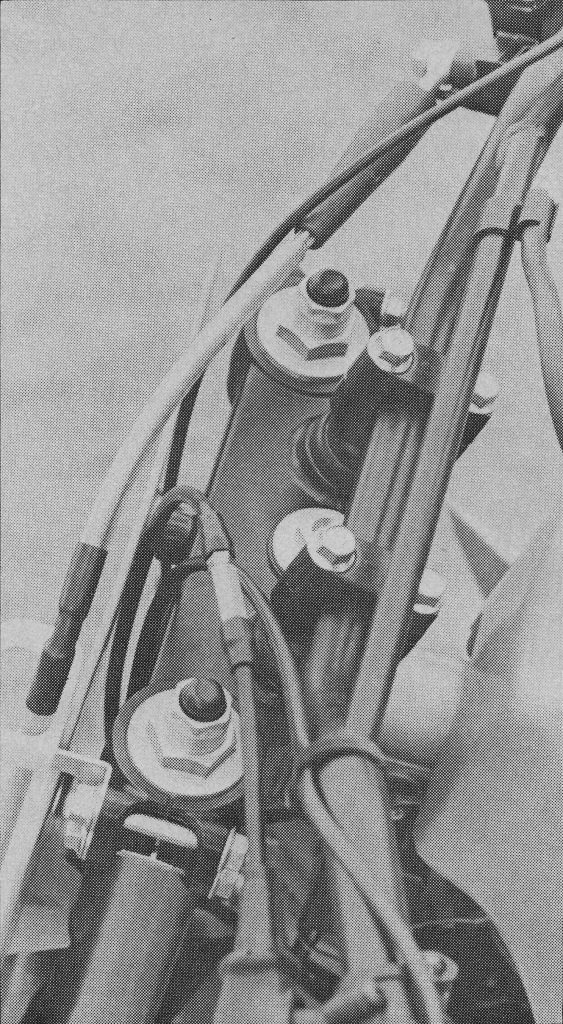

A redesigned airbox for 1985 used a snorkel routed along the frame backbone to draw cool air into the motor. Dubbed the Fresh Air Intake System (FAIS) this new design was added to all the full-sized KX models. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

A redesigned airbox for 1985 used a snorkel routed along the frame backbone to draw cool air into the motor. Dubbed the Fresh Air Intake System (FAIS) this new design was added to all the full-sized KX models. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the 250 division, the KX was little more than an afterthought in 1984. The machine offered up-to-date technology with liquid cooling, a powerful front disc binder, and their Uni-Trak single shock suspension, but its performance turned out to be less than the sum of its parts. The KX’s motor offered a strong low-to-mid surge that rocketed the machine out of corners, but its transmission was notchy, and its clutch was nearly hopeless. The long and tall chassis made turning a chore, and the suspension bottomed, banged, and bucked its way around the track. Its oversized ergonomics fit tall pilots well, but unless you had the inseam of Paul Bunyan, there were better 250 choices available in 1984.

All-new bodywork for 1985 slimmed the KX’s pilot’s compartment, increased rider protection, and did away with most of the previous model’s quirky appearance. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

All-new bodywork for 1985 slimmed the KX’s pilot’s compartment, increased rider protection, and did away with most of the previous model’s quirky appearance. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

While Kawasaki’s 250 had failed to garner much success in 1984, its smaller brothers had captured shootout victories in all their respective divisions. The KX60, KX80, and KX125 swept their competition with right-sized chassis, capable handling, and rompin’ stompin’ motors. For 1985, Kawasaki looked to bring some of that small-bore success to the 250 class by completely redesigning their deuce-and-a-half platform. Everything from the chassis, to the bodywork, to the motor, was all-new, with an emphasis on improving handling, smoothing ergonomics, and boosting the usability of the KX’s powerband.

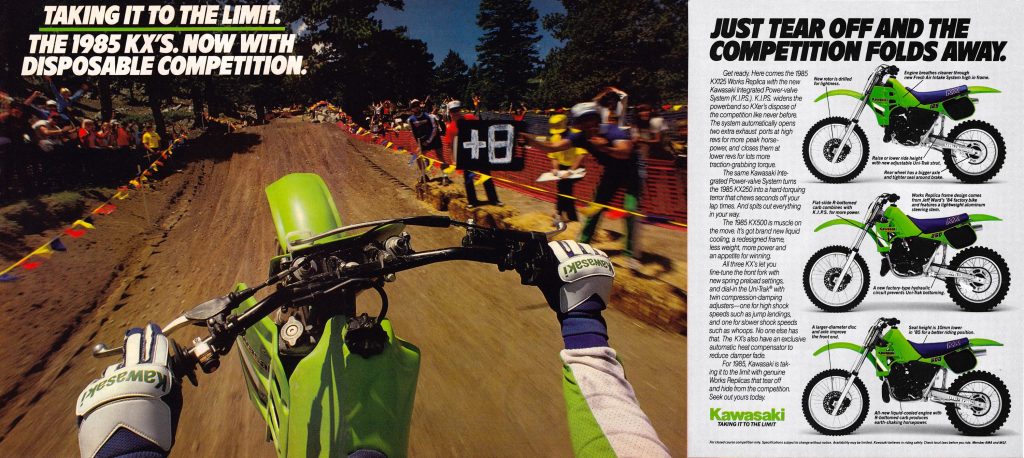

The iconic ad for the all-new 1985 KX models was so good that Kawasaki reused the same photo again in 1986. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The iconic ad for the all-new 1985 KX models was so good that Kawasaki reused the same photo again in 1986. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

At first glance, the most significant change on the KX250 for 1985 was its radically redesigned bodywork. In 1984, the KX250 offered a rather quirky visual package that was a combination of old and new-school designs. The disc brake and radiator shrouds pegged it firmly in the 1980s, but its rear fender-mounted number plates were a vestige of FIM regulations from the late 1970s. It was an odd combination of old and new styling that riders tended to either love for its uniqueness or loath for its lack of elegance.

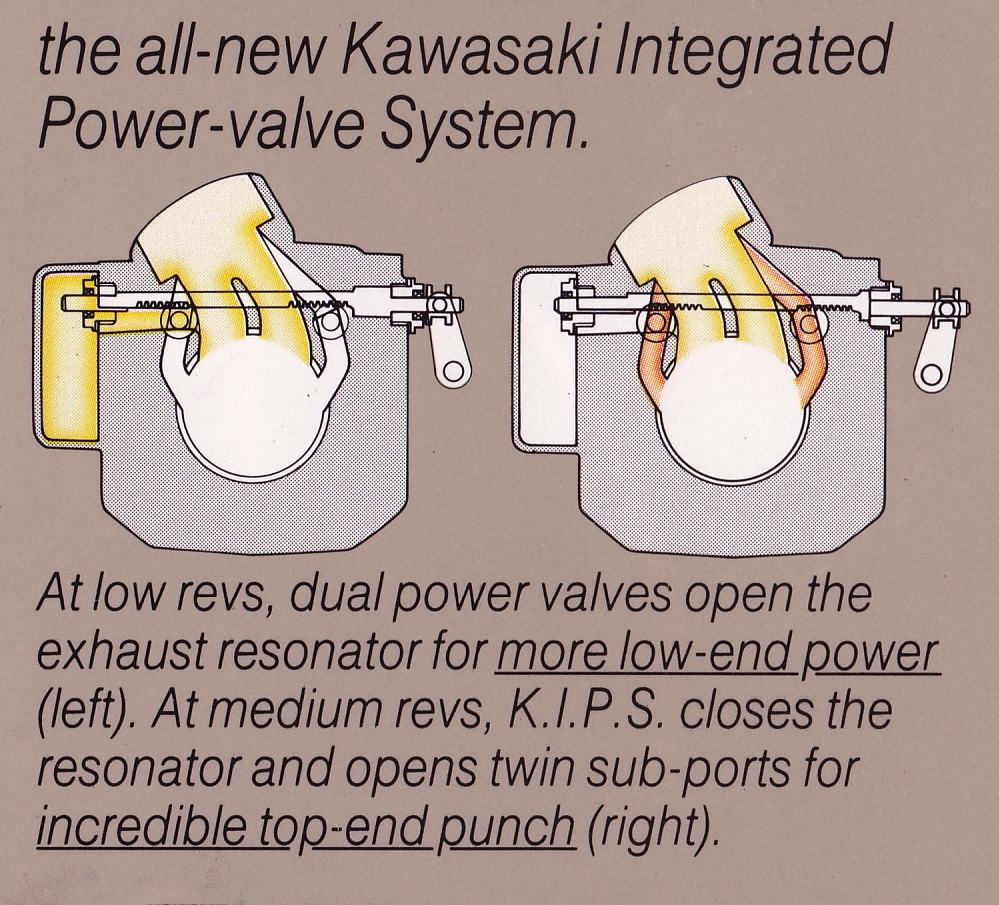

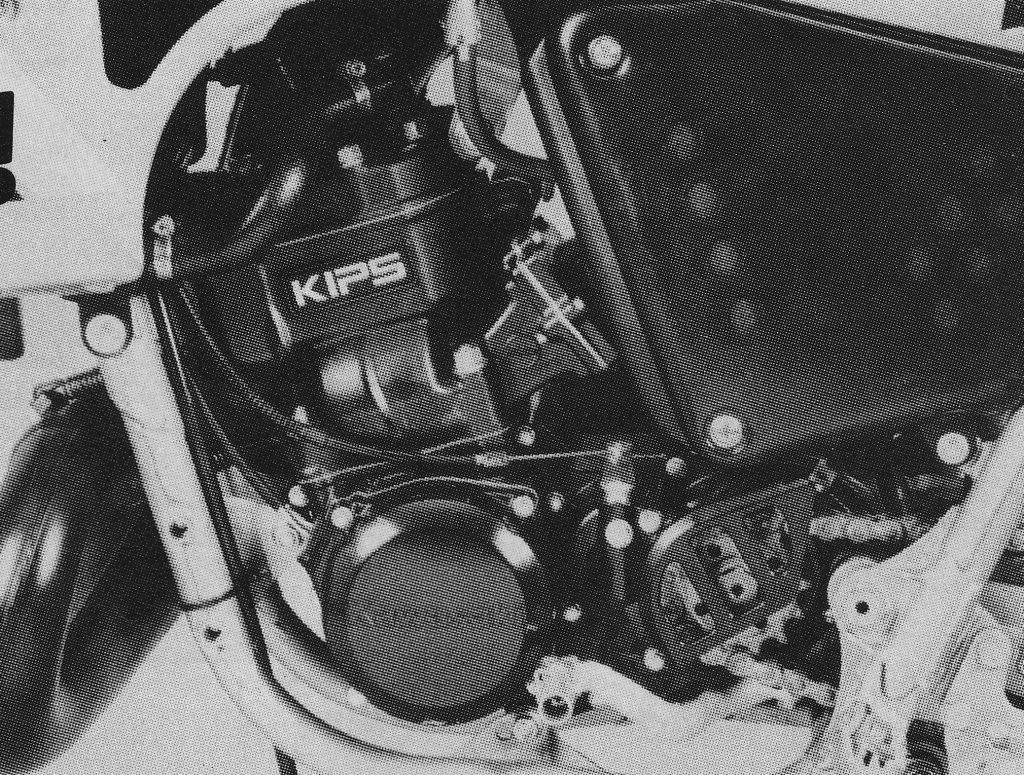

For 1985, Kawasaki added an all-new “power valve“ system to the KX250 to broaden performance. Coined the Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System (KIPS), this new design combined elements of Yamaha YPVS and Honda’s ATAC into one design. By both altering the porting and adding an exhaust resonance chamber, Kawasaki believed they could provide the ultimate combination of power and control. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1985, Kawasaki added an all-new “power valve“ system to the KX250 to broaden performance. Coined the Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System (KIPS), this new design combined elements of Yamaha YPVS and Honda’s ATAC into one design. By both altering the porting and adding an exhaust resonance chamber, Kawasaki believed they could provide the ultimate combination of power and control. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1985, the KX250 adopted the more mainstream look introduced on the KX125 in 1984. This meant sleeker lines, more compact dimensions, and a retirement of the love-it-or-hate-it rear fender in use since 1982. Up front, the new fender was longer and wider for increased mud protection and no longer employed the very “Euro” alloy fender brace seen in 1984. In the rear, an all-new design deleted the integrated number plates and offered a lower and longer profile that cleaned up the styling and reduced the chances of being whacked in the backside in the rough. An all-new tank offered 2.1 gallons of capacity and afforded a slimmer layout to make sliding forward in turns easier. Repositioned radiators sat 2.12 inches lower on the frame and intruded less into the pilot’s compartment. An all-new blue saddle featured a handsome redesign of the KX logo and offered a 10mm lower seating position to accommodate a wider cross-section of riders. The redesigned side plates afforded increased protection from the hot exhaust and reduced the amount of roost flung on the rider from the rear wheel. The overall layout of the KX was much improved for riders below six feet in height with the machine adopting an ergonomic feel more in line with its Japanese rivals. While the new layout was well received by most, long-time Kawasaki faithful could opt for the optional taller seat and reverse the offset bar mounts if they preferred the stretched-out feel of the older green machines.

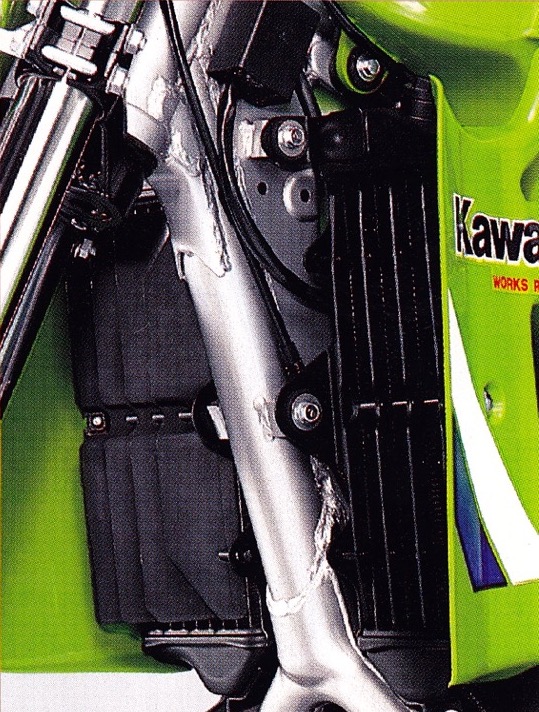

New radiators for 1985 were longer and deeper for improved cooling and mounted two inches lower on the chassis to slim the rider compartment and improve handling. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

New radiators for 1985 were longer and deeper for improved cooling and mounted two inches lower on the chassis to slim the rider compartment and improve handling. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

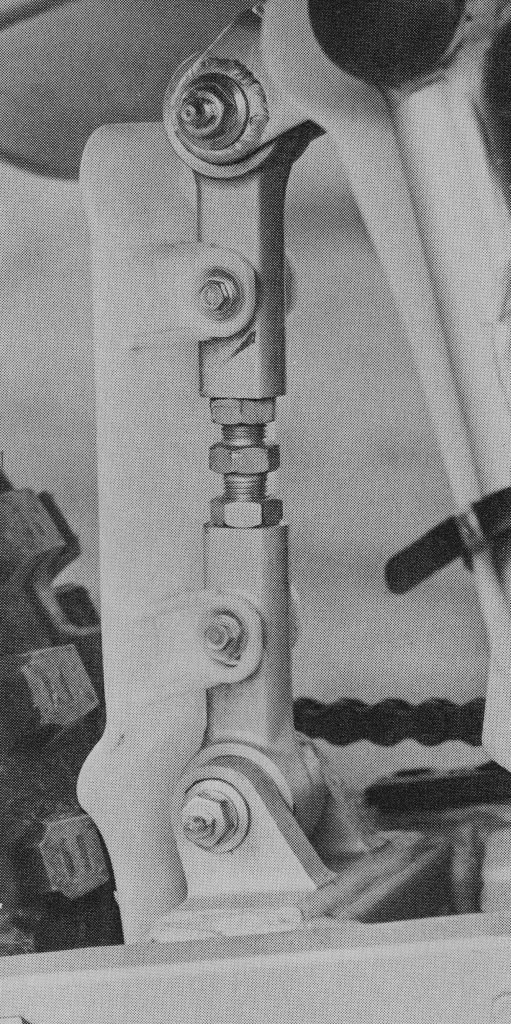

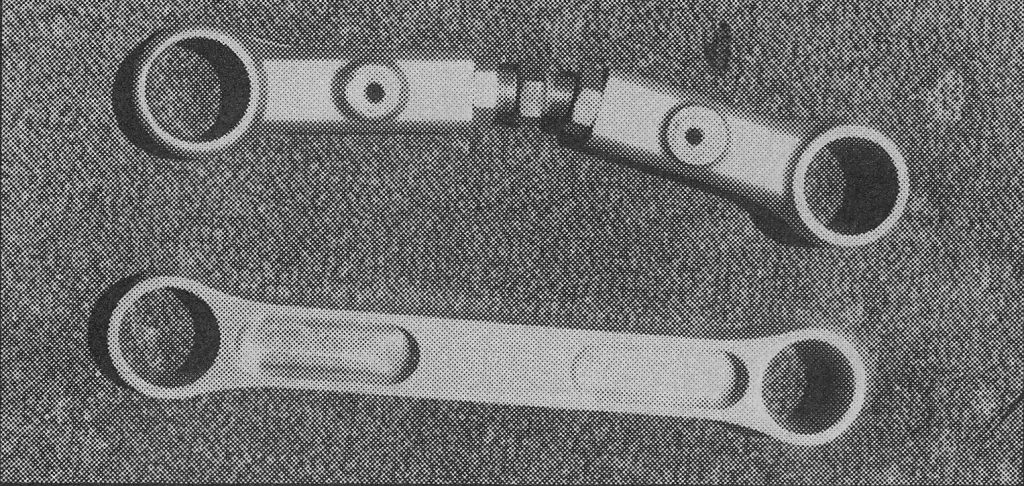

In addition to the redesigned bodywork, the ’85 KX250 featured a complete reworking of the chassis to improve handling and reduce weight. An all-new “high-tension steel” (HTS) frame featured a reduction in overall size and more aggressive geometry for an improved steering feel. The wheelbase was reduced by nearly an inch and additional gusseting was added in critical areas to help prevent the cracking issues Kawasaki’s frames had become notorious for. An all-new Uni-Trak rear suspension system featured a redesigned linkage that allowed the ride height of the machine to be fine-tuned using an adjustable rocker-arm strut. While Kawasaki touted this new feature, they also curiously advised against using it due to the danger of an improper adjustment causing a serious failure. If the strut was shortened to reduce the seat height, it could also cause the rear suspension to bottom harshly and cause the strut to bend or break. If this was a legitimate concern, it begs the question of why this feature ever made it to the production machine. Perhaps this concern was unanticipated until it was too far into production to make a change. Regardless of the reasoning, Kawasaki made it clear in all their press briefings that it was best to not mess with this adjuster if possible.

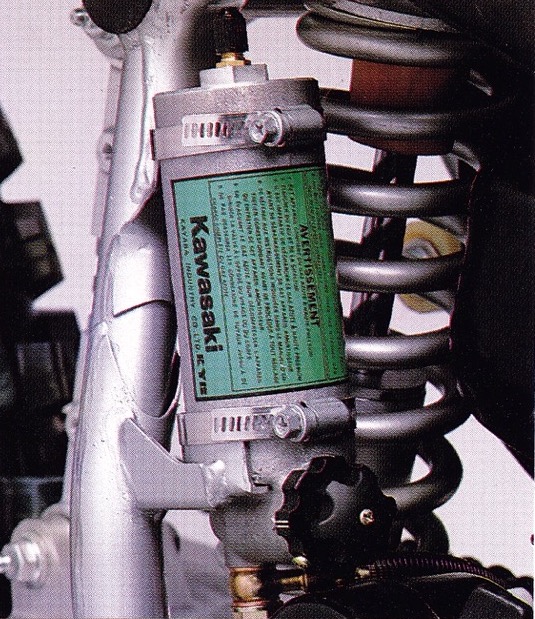

An all-new Kayaba shock for 1985 added high and low-speed compression adjustments and a new heat-compensating valve to combat fading. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

An all-new Kayaba shock for 1985 added high and low-speed compression adjustments and a new heat-compensating valve to combat fading. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the suspension front the 1985 KX250 featured one of the most advanced shocks ever offered on a production machine. The all-new Kayaba damper broke new ground by offering separate adjustments for both high and low-speed compression damping. This was more than a decade before this sort of multi-level adjustability would become commonplace within the industry. The shock offered 12.6 inches of travel with four selectable settings for high-speed compression and twelve settings for low-speed control. Rebound damping could also be adjusted with four settings available. In addition to its nearly unlimited adjustability, the new shock featured an innovative system to fight fading through the use of an automatic heat compensator. As temperatures within the shock increased, a tapered needle valve was engaged to increase the damping force. With these innovations, the KX250 offered the most advanced rear suspension available on a production machine in 1984.

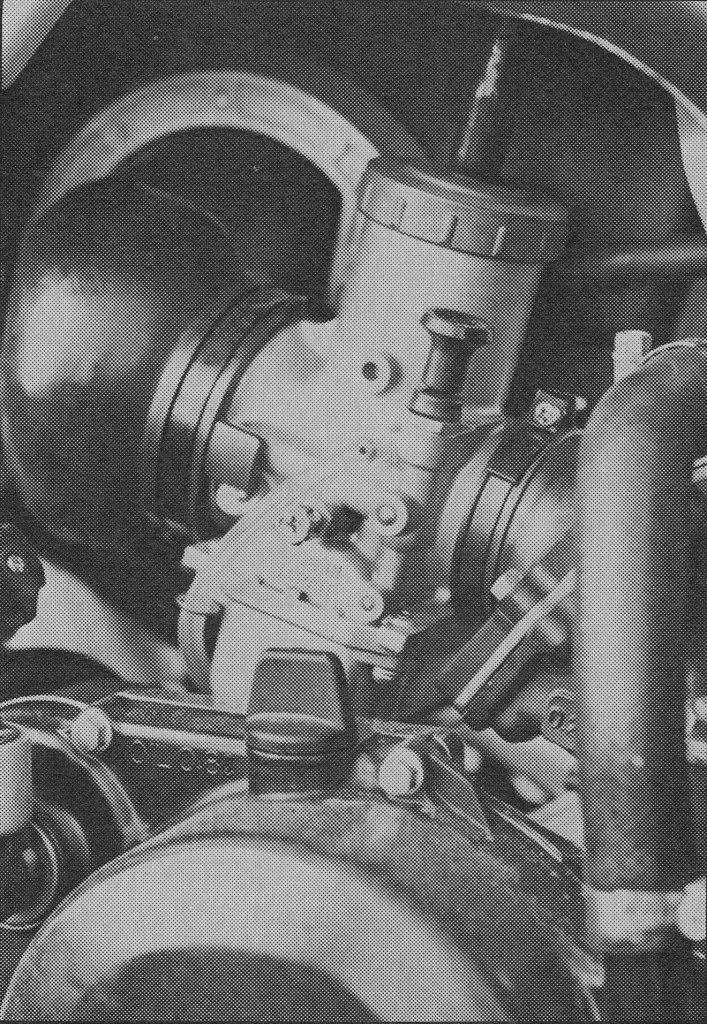

The 40mm VM40SS Mikuni carburetor employed on the KX250 grew 2mm in size for 1985 and added an innovative new “R-slide” to reduce intake turbulence for improved throttle response. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The 40mm VM40SS Mikuni carburetor employed on the KX250 grew 2mm in size for 1985 and added an innovative new “R-slide” to reduce intake turbulence for improved throttle response. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Up front, the 1985 KX250 was far more conventional in its design. All-new 43mm Kayaba forks offered 11.8 inches of travel and eight available adjustments for compression damping. Rebound control was not externally adjustable but there was a new three-way mechanical adjuster built into the top of each fork that could be used to fine-tune spring pre-load. Internally, the forks remained a traditional damper-rod design but new alloy internals reduced weight for 1985. Revised damping settings looked to improve the ’84 fork’s abysmal performance and a new alloy steering stem reduced weight. To lessen the chance of snagging the forks in a rut, fork protrusion below the front axle was reduced for ’85 and the fork gators of 1984 were deleted to allow more cooling air to make it to the repositioned radiators. Both front and rear axles were upgraded for 1985 with the front growing 2mm and the rear gaining 3mm in diameter. Braking continued to be handled by a front disc/rear drum combination, with the rear gaining a better-sealing backing plate and the front adopting a 10mm larger rotor for 1985.

Trick external preload adjusters for the forks and reversible offset bar clamps helped make the KX one of the most innovative machines in its class in 1985. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Trick external preload adjusters for the forks and reversible offset bar clamps helped make the KX one of the most innovative machines in its class in 1985. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

On the motor front, the KX250 was just as all-new for 1985. In 1984, the KX250 offered a strong motor that hit hard but signed off fast. It was quick from corner to corner but lacked the strong top-end pull of class leaders like the Honda CR250R. In 1985, Kawasaki looked to broaden the KX’s power profile by implementing their version of a “power valve” for the first time. Coined the Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System (KIPS), this new design incorporated elements of both the variable port timing of the YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) and the exhaust resonance chamber of the Honda ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) into one design. By both varying the exhaust port timing and altering the geometry of the exhaust system, Kawasaki’s engineers believed they could provide the optimal combination of power and usability. To accommodate the new KIPS mechanism, Kawasaki’s engineers had to dial up a complete redesign of the KX’s motor. The cylinder, head, cases, and bottom end of the motor were all reconfigured to work with the new variable exhaust system. The redesigned top end maintained the bore and stroke of the old design but featured all-new porting and repositioning of the main exhaust port to the center of the cylinder. Displacement remained at 249cc, and the motor retained the same 9.1:1 compression ratio it had used in 1984. Redesigned coolant passages in the cylinder and head improved coolant flow and helped prevent detonation under heavy loads. To help address the ignition failures that plagued the KX the year before the lead wire terminal was reinforced and the crankshaft contacts were enlarged to assure a solid connection. The CDI’s ignition curve was also remapped to optimize throttle response and provide a smoother delivery of power.

The 249cc KIPS mill in the KX250 was packed with power in 1985. It was less strong down low than the Honda and Yamaha but came on like a ton of bricks in the midrange. Top-end power was much improved over the year before but screaming it was not the most effective way to use its potent powerband. Photo Credit: Brian Waingrow

The 249cc KIPS mill in the KX250 was packed with power in 1985. It was less strong down low than the Honda and Yamaha but came on like a ton of bricks in the midrange. Top-end power was much improved over the year before but screaming it was not the most effective way to use its potent powerband. Photo Credit: Brian Waingrow

For 1985, Kawasaki added the ability to adjust the KX’s ride height with an adjustable Uni-Trak strut. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

For 1985, Kawasaki added the ability to adjust the KX’s ride height with an adjustable Uni-Trak strut. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Feeding fuel to the redesigned top end was an all-new carburetor and intake system for 1985. An all-new airbox increased volume and an innovative new intake system drew air directly from behind the front number plate. Dubbed the Fresh Air Intake System (FAIS), the new design consisted of a snorkel that ran from behind the radiators along the main frame backbone to the top of the airbox. This allowed the KX to draw cooler and fresher air into the motor for improved performance. In addition to the freer-breathing airbox, the new KX250 adopted a redesigned reed-valve and all-new intake manifold for 1985. The new reed valve featured air guides in its design to reduce turbulence and eight works-style carbon-fiber reeds to provide lightning-quick throttle response. A new 40mm (2mm larger than the 1984) Mikuni mixer fed fuel to the redesigned engine and featured an innovative flat-bottomed “R-slide” that Kawasaki claimed provided better atomization of fuel at low RPM. New radiators for 1985 were longer and deeper for improved cooling but also narrower to provide a slimmer pilot’s compartment. The new exhaust tucked in better at the tank and featured an all-new shape designed to work with the KIPS.

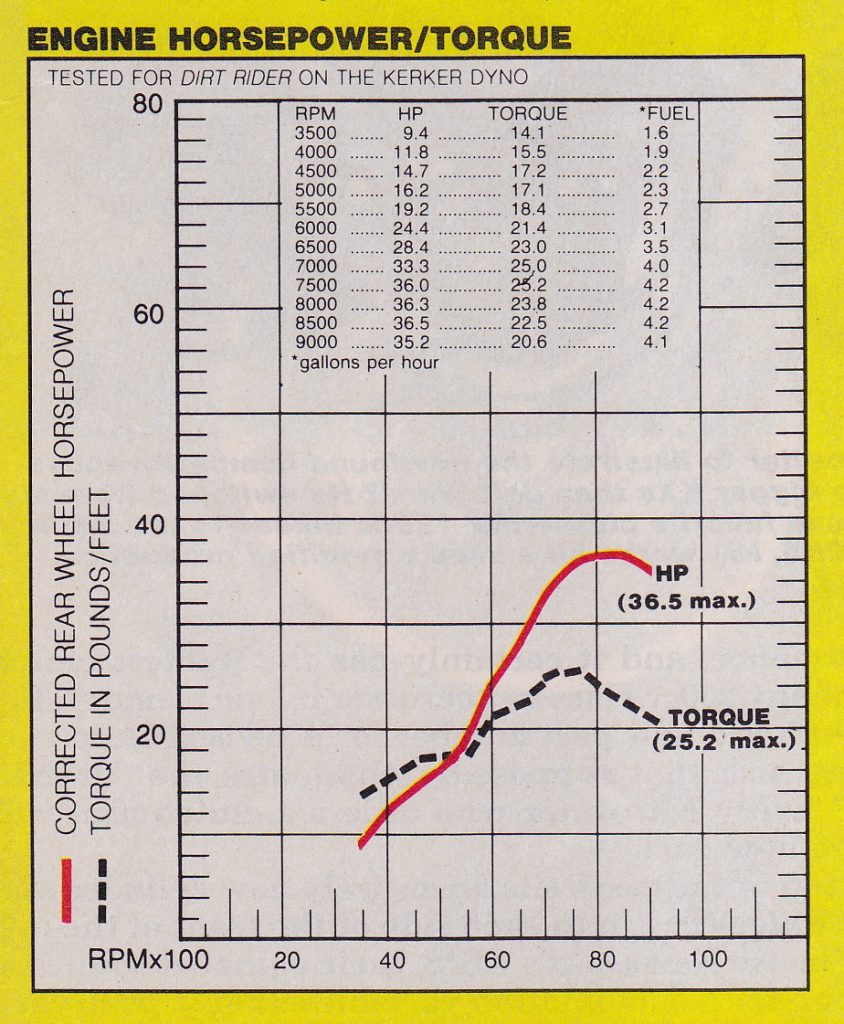

On Kerker’s dyno the KX250 pumped out a peak of 36.5 horsepower. This put it at the absolute top of the 1985 250 class. While its impressive horsepower numbers pointed to its potency, most riders preferred the chunky low-mid power of the Yamaha over the mid-range blast of the green machine. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On Kerker’s dyno the KX250 pumped out a peak of 36.5 horsepower. This put it at the absolute top of the 1985 250 class. While its impressive horsepower numbers pointed to its potency, most riders preferred the chunky low-mid power of the Yamaha over the mid-range blast of the green machine. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the bottom end, the KX featured all-new cases that incorporated the ball-ramp governor and hardware needed to power the KIPS mechanism. An all-new clutch moved to a floating-type engagement for the hub and redesigned clutch arm for an improved feel. The clutch-side case lacked a quick-change cover, but there was a handy sight window built into the design that allowed for quick oil inspections. The transmission remained a five-speed close-ratio design with all the ratios unchanged from 1984. A new shifter featured aluminum construction, a folding tip, and a revised shape for a more positive engagement.

By far the biggest flaws in the Kawasaki motor package for 1985 were its recalcitrant clutch and stubborn transmission. Despite an all-new hub design, the clutch continued to be grabby, difficult to modulate, and averse to serious abuse. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

By far the biggest flaws in the Kawasaki motor package for 1985 were its recalcitrant clutch and stubborn transmission. Despite an all-new hub design, the clutch continued to be grabby, difficult to modulate, and averse to serious abuse. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

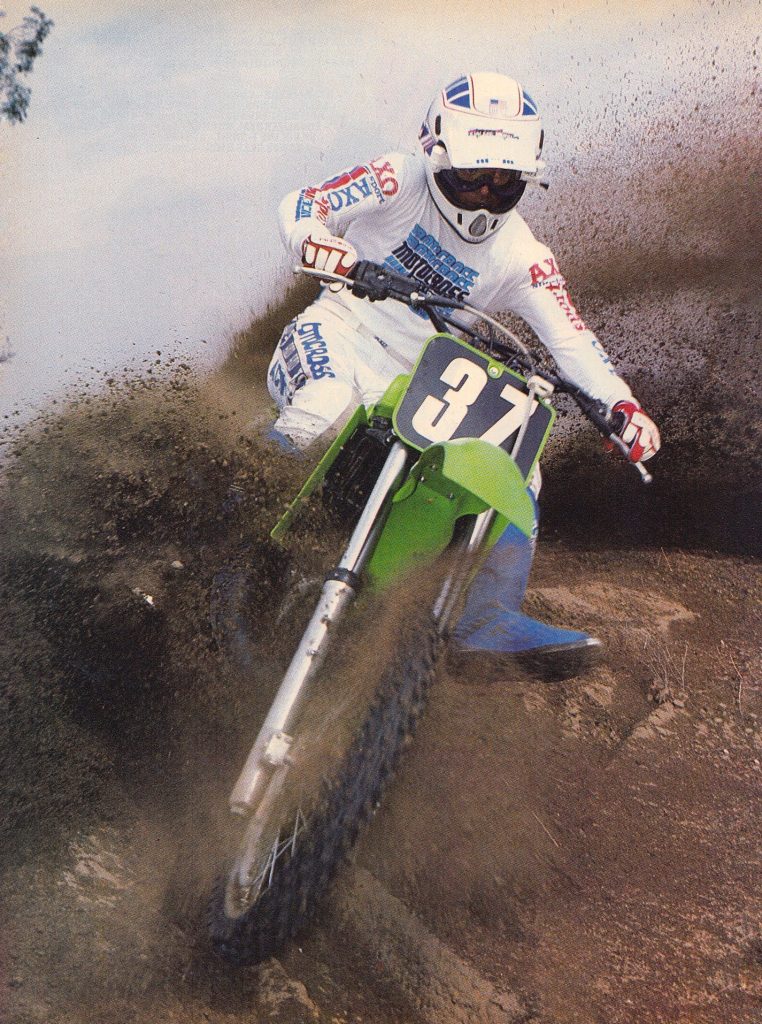

On the track, the all-new KIPS motor was different, but not necessarily better than the 1984. The new motor provided less torque than the year before, but a stronger midrange and longer pull on top. This lack of grunt made the green machine trickier to get hooked up out of corners and less responsive than tractors like the brawny Yamaha YZ250. Once on the pipe, the KX was competitive with anything in the class, and the bike’s new-found top-end pull made it more appealing for fast guys who found the old motor somewhat lacking. At a peak of 36.5hp, the KX was the strongest 250 Dirt Rider tested in 1985, outpowering the Yamaha by nearly half a horsepower.

While the KX250 had plenty of power, its lack of low-end, hard-hit, and grabby clutch made smoothly exiting turns more difficult than on its competitors. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

While the KX250 had plenty of power, its lack of low-end, hard-hit, and grabby clutch made smoothly exiting turns more difficult than on its competitors. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

While the KX offered plenty of thrust, its clutch and transmission continued to be a major hindrance to its performance. The redesigned clutch offered a light pull but it continued to be a chirping, snatching, and grabbing mess. The machine’s lackluster low-end response demanded the rider use a lot of clutch out of turns and this quickly exceeded its modest tolerance for abuse. The clutch’s on/off engagement and aversion to hammering made the bike’s power significantly harder to use and even highly-skilled riders found it difficult to modulate the KX’s abrupt powerband effectively. Out of turns, the clutch bucked and lurched, and executing the next shift often required the rider to back off the throttle. On paper, the new motor was highly competitive, but its grabby clutch and recalcitrant transmission greatly hindered its effectiveness on the track.

The 250 class was comprised of a lot of flawed machines in 1985. Yamaha owned the motor of doom but was saddled by atrocious suspension. The Honda had the best detailing, a torquey motor, and fantastic looks, but it lacked the horsepower to run at the front. The Suzuki owned the crown for the best rear suspension, but like the Honda, its mellow motor needed more ponies to be competitive. In the Kawasaki camp, you had big power, slim ergos, and a high-tech suspension, but its poor clutch and lack of grunt made it a tricky machine for less-skilled riders to manage. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The 250 class was comprised of a lot of flawed machines in 1985. Yamaha owned the motor of doom but was saddled by atrocious suspension. The Honda had the best detailing, a torquey motor, and fantastic looks, but it lacked the horsepower to run at the front. The Suzuki owned the crown for the best rear suspension, but like the Honda, its mellow motor needed more ponies to be competitive. In the Kawasaki camp, you had big power, slim ergos, and a high-tech suspension, but its poor clutch and lack of grunt made it a tricky machine for less-skilled riders to manage. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the handling front, the KX was improved but still a step behind the best-performing machines in the class. At 218 pounds on Dirt Bike’s scale, the KX was three pounds lighter than the 1984 KX250 and the lightest of all the Japanese 250 offerings in 1985. This paid major dividends on the track where the KX felt nimble in the air and easy to throw around. It was a capable jumper and nearly everyone commented on how much lighter the new machine felt compared to the year before. Turning precision was noticeably improved over previous Kawasaki offerings but it remained less precise than shredders like the Honda CR250R. In the turns, the KX’s front end never felt fully planted, and the machine tended to stand up mid-corner unless the rider was precise with his technique. On exit, the abrupt power and difficult-to-modulate clutch made it challenging to get the KX hooked up and the machine tended to either spin the rear tire or grab traction suddenly and unload the front end. At speed, the KX was solid with none of the headshake that could make the Honda a biblical-level experience. The occasional kick from the rear shock could upset the chassis, but the Kawasaki never tried to rip your hands off the bars or threaten to swat you like a fly if you hit an unexpected bump at speed. Overall, it was a solid-handling package that jumped well and went straight with confidence but demanded more skill and concentration in the turns than its competitors.

Good forks and a great front brake highlighted the front end of the KX250 in 1985. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Good forks and a great front brake highlighted the front end of the KX250 in 1985. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

With the most advanced suspension in the class, the KX250 had a lot going for it in 1985. The Uni-Trak was almost infinitely adjustable with its variable linkage and three-way damping adjustability. For those versed in suspension theory, this opened a world of possibilities, but it also made it very easy to get lost in the suspension weeds. The KX’s many available settings made it easy to get things quite wrong, but if you got it properly dialed, the KX offered a very competitive rear suspension package. Fast riders thought the stock spring was a bit soft and the rebound damping of the KYB shock could be a bit quick, but overall, it did a very good job of smoothing out the track. As long as you did not fiddle with the rear strut, bottoming was no issue and the KX’s rear suspension was ranked by many as one of the best available in 1985.

The Uni-Trak rear suspension on the KX offered a ton of adjustability in 1985. While fast guys needed a stiffer spring, most riders found its performance more than acceptable in stock condition. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The Uni-Trak rear suspension on the KX offered a ton of adjustability in 1985. While fast guys needed a stiffer spring, most riders found its performance more than acceptable in stock condition. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Up front, the KX’s KYB forks were much less of a black box of mystery and performed very well in most instances. Once again, the stock springs were a bit soft for fast guys and those same riders complained the rebound was a bit too quick. Without an external adjustment for rebound damping, this was not easily addressed, but riders of more modest talent found the forks to be plush and well-sorted. The externally adjustable spring pre-load was taken right off Jeff Ward’s works racer and afforded a level of customizability not found in its competitors. With this adjustment and eight settings for compression damping, most riders were able to find a setting that worked well. Some riders did complain of stiction in the mid-stroke when the KX was new, but this seemed to lessen as the forks broke in. While not perfect, the KX’s stock forks were good overall performers and certainly raceable in stock condition for most riders below the pro class.

The new adjustable strut turned out to be a major failure point for the ’85 KX. Hard landings could bend it at the adjustment point and fast riders were well advised to watch it very carefully or replace it altogether with an aftermarket unit like the one featured above from DMC. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The new adjustable strut turned out to be a major failure point for the ’85 KX. Hard landings could bend it at the adjustment point and fast riders were well advised to watch it very carefully or replace it altogether with an aftermarket unit like the one featured above from DMC. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the detailing front, the KX was a bit of a mixed bag in 1985. Technically, it was the most advanced machine in the class with a works-level shock, dual-function power valve, trick air intake, and zoot capri forks. Its adjustable strut offered the ability to vary ride height, and its offset reversible bar clamps offered works-level customization. It was a bike for the eighties with all the doodads and gizmos any self-respecting moto-head would want. While this level of technology was welcomed by most, not every innovation proved a blessing. The multi-adjuster shock’s function was not well-explained in the owner’s manual and many found its multitude of settings inscrutable. The new adjustable strut also proved a major point of failure with many riders experiencing bending at the adjustment point. Frame breakages continued to be common, and the footpegs were not up to serious abuse. Plastic and hardware quality were poor, with fenders that easily cracked and bolts that easily stripped. Stock sprocket and chain quality were of the pot metal variety, but this was par for the course for Japanese machines of the time. Overall motor reliability was good, but the KIPS added significant complexity to a top-end service, and the electrofusion coating Kawasaki used for the cylinder liner meant a seizure could be extremely costly. Vibration was also the heaviest of the Big Four with more than a bit of tingle making it through the KX’s bars.

Flat turns and slick dirt played major havoc with the KX’s turning manners. With a berm and some traction, it was capable of changing direction, but its front end never felt as planted and confidence inspiring as many of its rivals. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Flat turns and slick dirt played major havoc with the KX’s turning manners. With a berm and some traction, it was capable of changing direction, but its front end never felt as planted and confidence inspiring as many of its rivals. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Trick rubber covers protected the throttle, clutch, and front brake controls, and the stock bar bend was liked by most. The new bodywork was slim and comfortable with many riders split between the Honda and Kawasaki as having the best layouts of 1985. Brake action front and rear were strong and positive with the front disc finishing behind only the excellent dual-piston Honda binder for power. While strong, more than a few riders noted issues with air contamination within the Kawasaki’s hydraulic system. This quickly turned the KX’s front brake feel to mush with the Kawasaki demanding more frequent bleedings than its rivals.

Trick, powerful, and at the cutting edge of design, the KX250 was a flawed but competitive 250 choice in 1985. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Trick, powerful, and at the cutting edge of design, the KX250 was a flawed but competitive 250 choice in 1985. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Overall, the 1985 Kawasaki KX250 turned out to be a solid machine utterly undone by an unruly clutch and notchy transmission. The new KIPS motor pumped out the most power in the class and its sophisticated suspension offered works-level tunability. Its mediocre turning, soft suspension, and lack of low-end made it a tough sell for Supercross, but its potent power, slim lines, and plush suspension earned it a lot of fans in 1985. Even with its grim clutch, cantankerous shifting, and spotty build quality, the KX was a popular choice for many. Fast, futuristic, and flawed, the 1985 KX250 was the quintessential mid-eighties motocross machine.