For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the last of Suzuki’s true Full Floater tiddlers, the 1985 RM125.

Refinement rather than reinvention was the hallmark of Suzuki’s 1985 efforts. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Refinement rather than reinvention was the hallmark of Suzuki’s 1985 efforts. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Today, Suzuki’s motocross fortunes are a bit in flux. The hiring of Ken Roczen has brought a bit of revitalized interest to the brand for 2023, but the lack of attentiveness the bosses in Hamamatsu have shown toward updating their products have many concerned about the long-term health of the RM Army. The Suzuki faithful will point to the lower price and largely competitive performance of their machines as prudence and wisdom in the face of ever-escalating costs within the sport. In truth, this argument has a lot of merit as the costs of the new 450s crest $10,000 and more racers look for less costly alternatives. The 2023 RM-Zs offer more performance than 90% of the buying public could ever need and do it at a significantly lower price point. For many, this makes modern Suzukis an attractive choice, but in the fashion conscience world of motocross, Suzuki’s perceived lack of interest in updating their machines can come off as apathy rather than shrewdness.

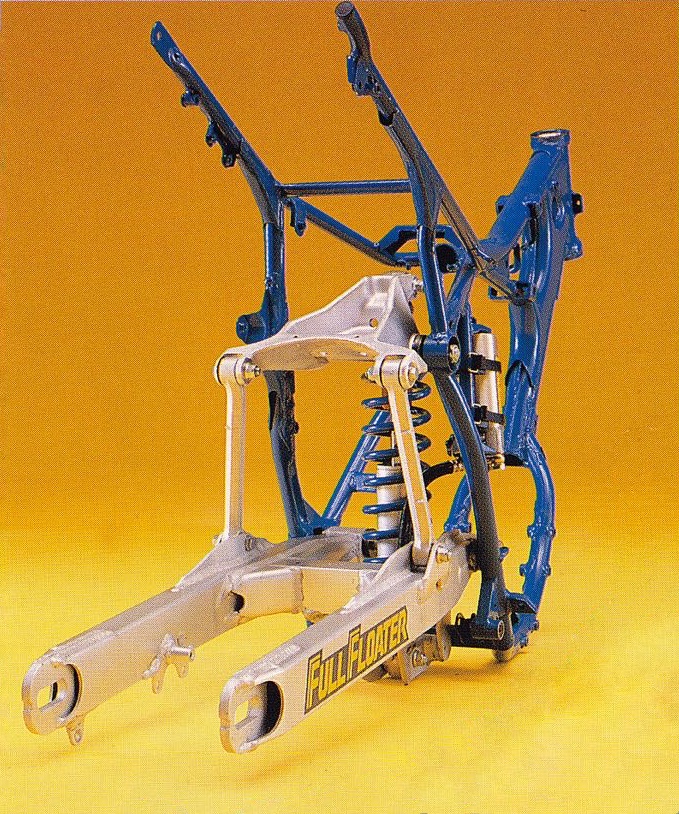

In 1981, Suzuki unveiled its revolutionary Full Floater rear suspension system and it powered the RM125 to a dominating class victory. From 1981 through 1985, the Full Floater was acknowledged as the best rear suspension in motocross. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1981, Suzuki unveiled its revolutionary Full Floater rear suspension system and it powered the RM125 to a dominating class victory. From 1981 through 1985, the Full Floater was acknowledged as the best rear suspension in motocross. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In the 1980s, Suzuki’s motocross outlook was very different. They were the first Japanese brand to make a major push into motocross in the late sixties and an absolute powerhouse of success through the 1970s and early 1980s. Riders like Joël Robert, Roger De Coster, Tony DiStefano, Danny Laporte, Gaston Rahier, Akira Watanabe, and Harry Everts brought the brand countless wins and Motocross titles during the “Me” decade. As the eighties began, the torch was passed to riders like Mark Barnett, Kent Howerton, Brad Lackey, and Eric Geboers who continued to rack up wins and titles for the smallest of the “Big Four” contenders. At the end of 1984, Suzuki captured an unprecedented tenth straight 125 World Motocross title with Michele Rinaldi at the controls. This accounted for every 125 World Motocross title run up to that point.

All-new in 1984, the RM125’s chassis was unchanged for 1985. Photo Credit: Suzuki

All-new in 1984, the RM125’s chassis was unchanged for 1985. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While Suzuki’s prowess on the world stage was largely attributable to the performance of their works machines, their production bikes during this era were nearly as well regarded. Introduced in 1975, Suzuki’s RM125 was a perennial class leader throughout the 1970s. Offering competitive power and excellent suspension, the RM battled with Yamaha’s YZ125 for class supremacy throughout the decade.

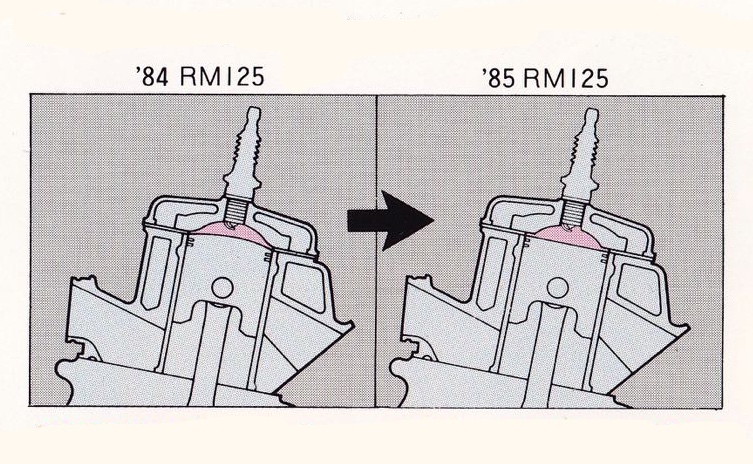

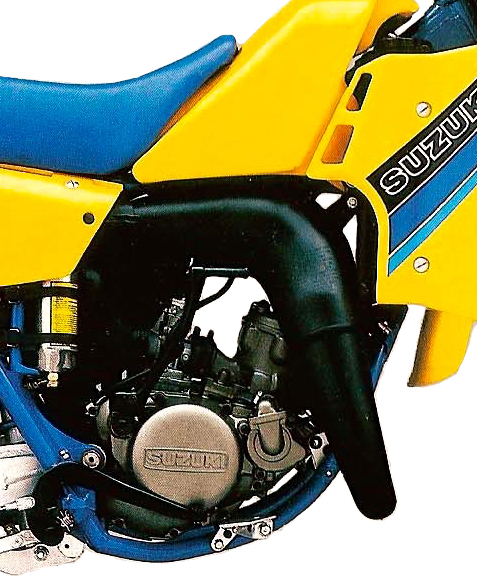

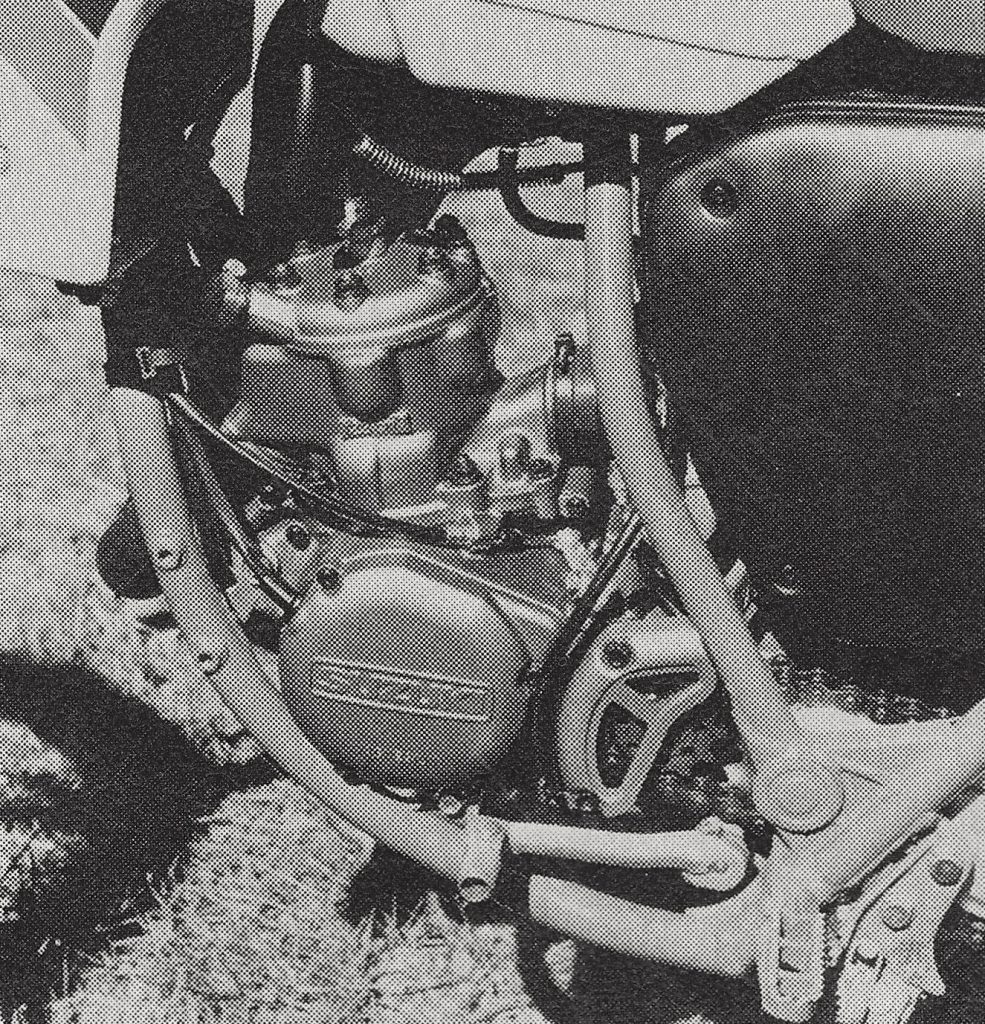

A new top end for 1985 featured revised porting and move to a flat-top piston. The RM’s lack of a variable exhaust valve or exhaust resonator left it as the only 125 in the Japanese field without one of these power-broadening features. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A new top end for 1985 featured revised porting and move to a flat-top piston. The RM’s lack of a variable exhaust valve or exhaust resonator left it as the only 125 in the Japanese field without one of these power-broadening features. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1981, Suzuki upped their game significantly with the introduction of their revolutionary all-new rear suspension system – the “Full Floater.” Named for its unique linkage that isolated the shock from the rest of the chassis at both the top and bottom of its mounting, the Full Floater signaled a quantum leap forward in rear suspension performance. With its powerful liquid-cooled motor and high-tech suspension, the RM125-X dominated the eighth-liter standings in 1981. Advances in engine design left the RM’s motor behind in 1982, but it continued to offer one of the best-handling and best-suspended packages in the class. Despite no longer offering the most power in the division, many riders still picked the RM125 as the best machine in the 1982 125 class.

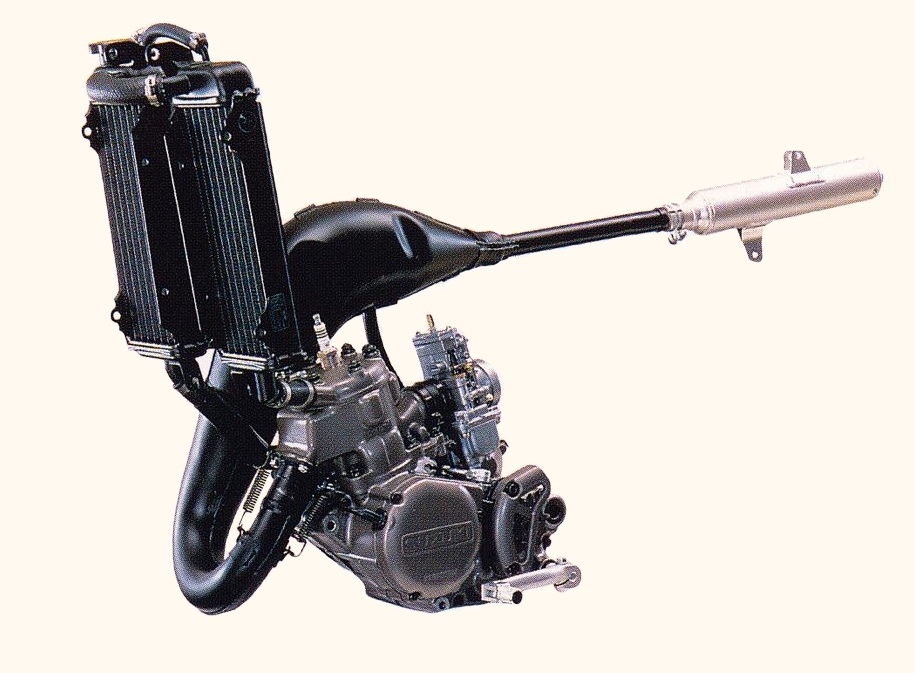

For 1985, a switch to silver for the motor gave the RM’s power plant a new look but its basic design was largely unchanged from the year before. New ratios for the transmission, revised porting, and a larger carburetor were all aimed at boosting power and making the RM’s previously peaky motor easier to ride. Photo Credit: Suzuki

For 1985, a switch to silver for the motor gave the RM’s power plant a new look but its basic design was largely unchanged from the year before. New ratios for the transmission, revised porting, and a larger carburetor were all aimed at boosting power and making the RM’s previously peaky motor easier to ride. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1983, the 125 class started heating up with majorly improved machines being offered by three of Suzuki’s Big Four competitors. All-new machines from Honda and Yamaha, and significant improvements made to Kawasaki’s offering, meant that the status quo was no longer going to be enough for Suzuki to keep its 125 crown. While the RM’s Full Floater continued to offer the best rear suspension in the class, its mellow motor and lackluster forks relegated it to the back of the ’83 125 class.

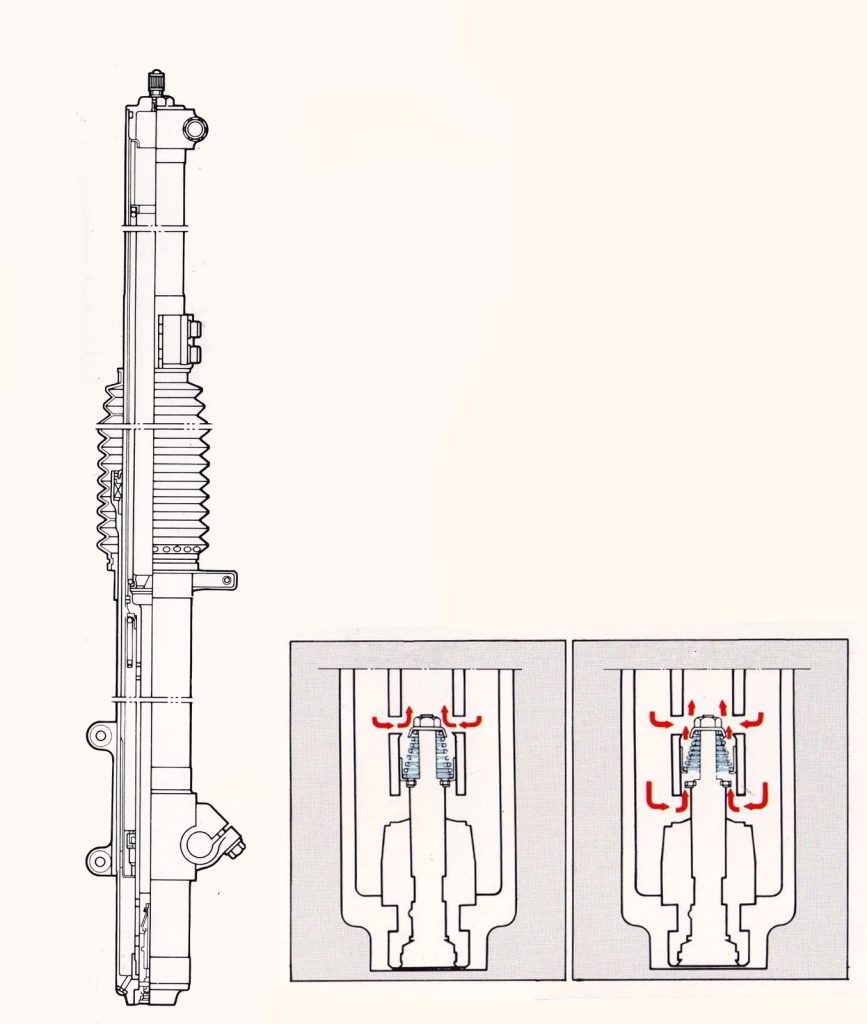

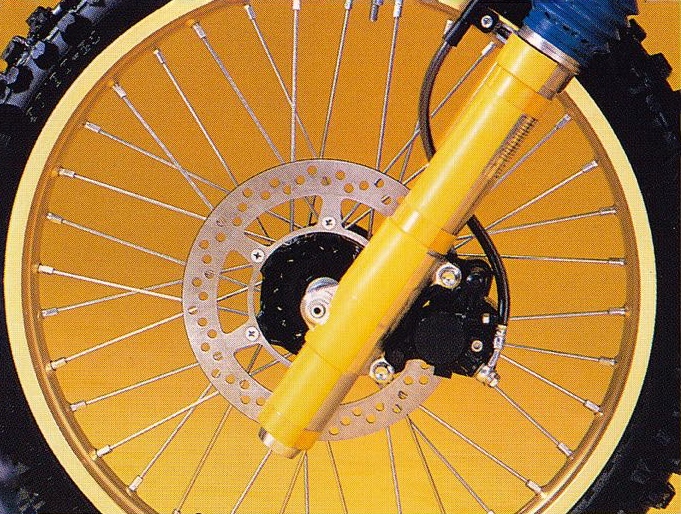

All-new 43mm Kayaba forks for 1985 added a great deal more adjustability and a new “proportional valve” designed to smooth out the fork’s action on hard hits. Photo Credit: Suzuki

All-new 43mm Kayaba forks for 1985 added a great deal more adjustability and a new “proportional valve” designed to smooth out the fork’s action on hard hits. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1984, Suzuki finally revamped their original ’81 design and introduced an all-new 125 platform. The overhauled RM featured an all-new chassis, beefed-up suspension, revised bodywork, and works styling. The blue paint for the frame and redesigned bodywork gave the RM a new look but the basic motor design remained largely unchanged from its 1981 roots. It continued to use Suzuki’s unique “Power Reed” intake which their engineers claimed combined the benefits of a piston port and reed valve intake into one design. An all-new airbox for 1984 simplified servicing and increased airflow to the 32mm Mikuni flat-slide carburetor and revised porting looked to broaden the RM’s power. Unlike the Yamaha YZ125 and Honda CR125R, the RM125’s motor continued to lack a variable exhaust valve to boost torque and broaden its power. This proved detrimental to the RM’s fortunes with the new motor continuing to lack the power to run at the front. It pulled well on top but lacked the low-end and midrange of its rivals. Improved in many ways, the all-new RM125 was once again the best-suspended machine in the class, but in a division ruled by power, that was not nearly enough to propel the Suzuki past its more potent rivals.

While its performance on the track continued to be without peer, other mitigating factors were quickly bringing the era of the original Full Floater to a close in 1985. A lawsuit challenging its origins and concerns over packaging, weight, and manufacturing costs would push Suzuki to retire the original Full Floater design after the 1985 season. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While its performance on the track continued to be without peer, other mitigating factors were quickly bringing the era of the original Full Floater to a close in 1985. A lawsuit challenging its origins and concerns over packaging, weight, and manufacturing costs would push Suzuki to retire the original Full Floater design after the 1985 season. Photo Credit: Suzuki

For 1985, Suzuki looked to recapture past 125 glory by adding a huge list of refinements to their well-liked, but underpowered ’84 package. First up was a slew of motor updates aimed at getting the powerband up to competitive levels. An all-new top-end featured revised porting, a redesigned piston, and a reconfigured head. Bore, stroke, and overall displacement remained unchanged from 1984 with the RM checking in at 123cc and a perfectly square 54mm x 54mm.

For 1985, the piston moved from a dome shape to a flat design, but the compression ratio remained unchanged at 8.8:1. In 1984, the stock RM’s piston had become notorious for cracking under hard use so an all-new supplier was contracted to manufacture them for 1985. The ’84 RM’s smallish 32mm carburetor was shelved in favor of a deeper breathing 34mm flat-slide VMS34SS from Mikuni and a new expansion chamber was added to boost midrange power. As in 1984, the RM’s mill continued to eschew any sort of variable exhaust port or exhaust resonance chamber. With Kawasaki adding their Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System (KIPS) to the KX125 in 1985, this left the RM as the only Japanese machine in the class without the benefit of this power-broadening feature. An all-new gearbox for ’85 added new ratios and beefed-up gearsets for improved reliability. The final drive was altered to work with the new powerband and gear ratios by dropping two teeth from the rear sprocket for 1985.

Yellow Domination: Today, Suzuki feels like something of an afterthought in professional racing but in 1985, they were the winners of ten straight 125 World Motocross titles, a feat proudly proclaimed on the front page of this 1985 RM125 brochure. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Yellow Domination: Today, Suzuki feels like something of an afterthought in professional racing but in 1985, they were the winners of ten straight 125 World Motocross titles, a feat proudly proclaimed on the front page of this 1985 RM125 brochure. Photo Credit: Suzuki

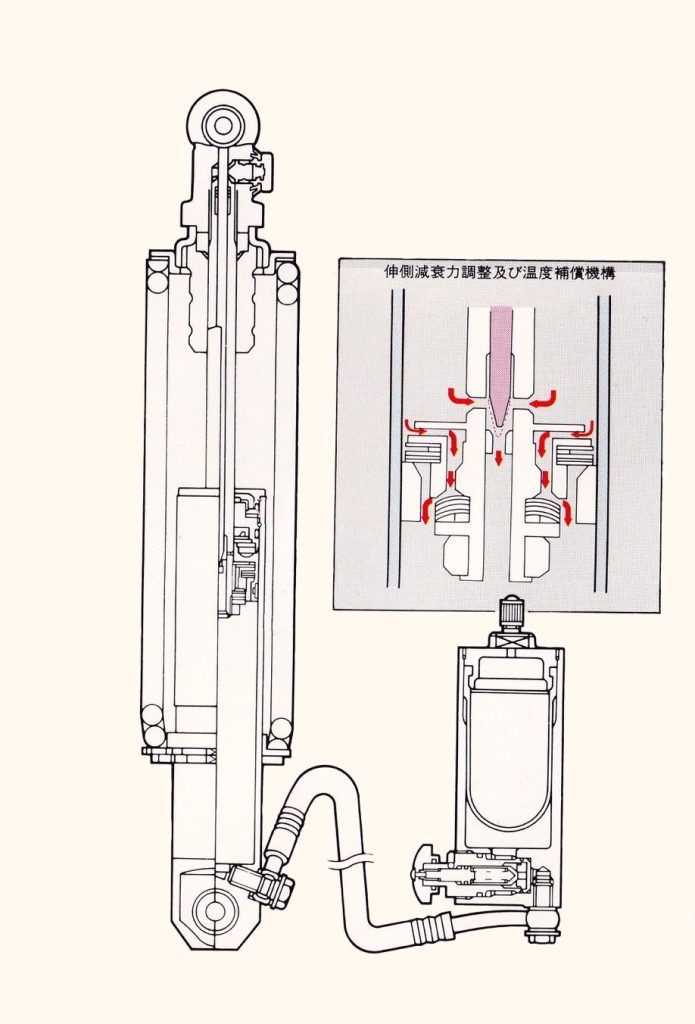

An all-new Kayaba shock for 1985 added a great deal of adjustability and a new valving system to provide a smoother ride. Photo Credit: Suzuki

An all-new Kayaba shock for 1985 added a great deal of adjustability and a new valving system to provide a smoother ride. Photo Credit: Suzuki

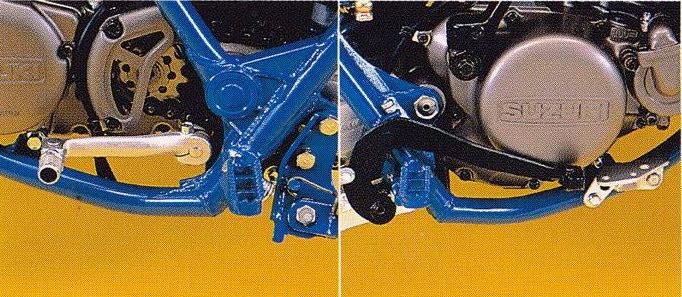

On the suspension front, the RM featured all-new components front and rear. The 43mm Kayaba conventional forks featured revised internals that increased the available compression settings from the ‘84’s eight to seventeen selectable settings for 1985. A new proportional valve was added to the compression system that Suzuki claimed would provide a more progressive damping feel on hard hits. Rebound damping was not externally adjustable but the forks did allow a bit of fine-tuning using Schrader valves on each fork cap. Fork travel was identical to 1984, with the legs offering the class standard 11.8 inches of movement.

A new hydraulic disc brake for the front brought the RM up to speed with its rivals in 1985. While the new binder was an improvement over the drum of 1984, its single-piston design and flexy plastic line imparted a mushy feel that was a step behind the stopping power offered by the other Big Four competitors. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A new hydraulic disc brake for the front brought the RM up to speed with its rivals in 1985. While the new binder was an improvement over the drum of 1984, its single-piston design and flexy plastic line imparted a mushy feel that was a step behind the stopping power offered by the other Big Four competitors. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In the rear, the ’85 RM featured an all-new Kayaba shock that also incorporated a proportional valve for smoother operation. The new damper was fully rebuildable and offered a significant increase in available adjustment. In 1984, the Full Floater boasted four available settings for compression and rebound damping. In 1985, that number was boosted to seventeen on compression and twenty on the rebound. The new shock offered 12.6 inches of travel and was valved to offer a smoother ride at low speeds and a more progressive feel as it moved into the firmer portion of its travel. Suzuki’s acclaimed original Full Floater linkage system remained intact with no significant changes for 1985. Complex and costly to manufacture and maintain, the original Full Floater remained revered for its performance, but forces were conspiring to bring its era as the top suspension in motocross to an end. Lighter and less costly bottom-link designs like those found on the Honda CRs were quickly finding favor and a lawsuit disputing the Full Floater’s origins was making its continued use unlikely. For 1985 it remained, but its days as the premier suspension system in motocross were numbered.

Finesse vs. firepower: In 1985, Suzuki ruled suspension and Kawasaki cornered the market on horsepower in the 125 division. While both camps had their fans, in the cutthroat world of one-two-five racing the green machine had the edge for most racers. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Finesse vs. firepower: In 1985, Suzuki ruled suspension and Kawasaki cornered the market on horsepower in the 125 division. While both camps had their fans, in the cutthroat world of one-two-five racing the green machine had the edge for most racers. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the chassis front, the RM125 was largely unchanged for 1985. By far the biggest addition was the all-new hydraulic front disc brake which finally brought the RM in line with its 125 rivals. The 240mm single-piston front binder was paired with a traditional rear drum, which was the class standard in 1985. All the bodywork was a carryover from the year before, with a switch to gold rims, the disc brake, and a coat of silver paint for the motor logging in as the major visual changes for ‘85. Chassis geometry was unchanged with the chromoly frame offering the same 29.7 degrees of rake and 4.8 inches of trail as in 1984. The wheels, switchgear, and componentry were all carryovers as well.

The motor changes made for 1985 yielded a powerband that was easier to ride but not really any faster than the year before. There continued to be very little torque off idle, but the RM did pick up sooner and pull stronger through the midrange. Top-end power was slightly down from 1984, but the RM continued to pull farther on top than any of its rivals. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The motor changes made for 1985 yielded a powerband that was easier to ride but not really any faster than the year before. There continued to be very little torque off idle, but the RM did pick up sooner and pull stronger through the midrange. Top-end power was slightly down from 1984, but the RM continued to pull farther on top than any of its rivals. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the track, the revamped ’85 RM offered an improved but not omnipotent 125 experience. The motor changes aimed at moving the RM’s powerband out of the stratosphere worked well with the new silver motor providing significantly more midrange pull than the year before. Low-end torque continued to be utterly nonexistent, but the motor no longer needed to be run up to the rev limiter to provide competitive thrust. Once past the black hole of the torque down low, the motor perked up and pulled well through a much-improved midrange and decent top-end hook. There was slightly less power at the upper end of the power curve than in 1984, but most riders below the pro class thought the move to the midrange was a smart one. With so little torque down low, the RM was significantly harder to ride than machines like the ultra-responsive KX125. It required lots of clutch out of corners and careful gear selection to make the most of its mid-and-up powerband. If you were quick on the clutch and kept the machine rolling through turns it could run with its rivals, but if you tried to play “stop and go” with a rider on a green machine you were going to eat roost as the Kwacker pulled away.

Going green: The 1985 125 class was dominated by Kawasaki and the power of their new KIPS mill. Of the other three contenders, Honda came the closest to unseating the KX with its broad power and flawless turning manners. Suzuki owned the suspension sweepstakes but the RM lacked the potency found in the red and green machines. Yamaha fans had the hardest go in 1985, with a machine that lacked the power, handling, and suspension finesse to run with its rivals. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Going green: The 1985 125 class was dominated by Kawasaki and the power of their new KIPS mill. Of the other three contenders, Honda came the closest to unseating the KX with its broad power and flawless turning manners. Suzuki owned the suspension sweepstakes but the RM lacked the potency found in the red and green machines. Yamaha fans had the hardest go in 1985, with a machine that lacked the power, handling, and suspension finesse to run with its rivals. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

While the new powerband was certainly an improvement, most riders still rated it behind the motors found on the KX and CR. In 1985, nothing in the class was in the same league as Kawasaki’s new KIPS-equipped powerhouse, but the Honda came the closest to giving it a run for its money. The RM’s utter lack of low-end made it a difficult sell to many, but fast riders did prefer its strong top-end to the mid-range only motor found on the YZ125. It was an engine that required skill to use effectively, but if you had the cajones to keep it pinned, it could run at the front.

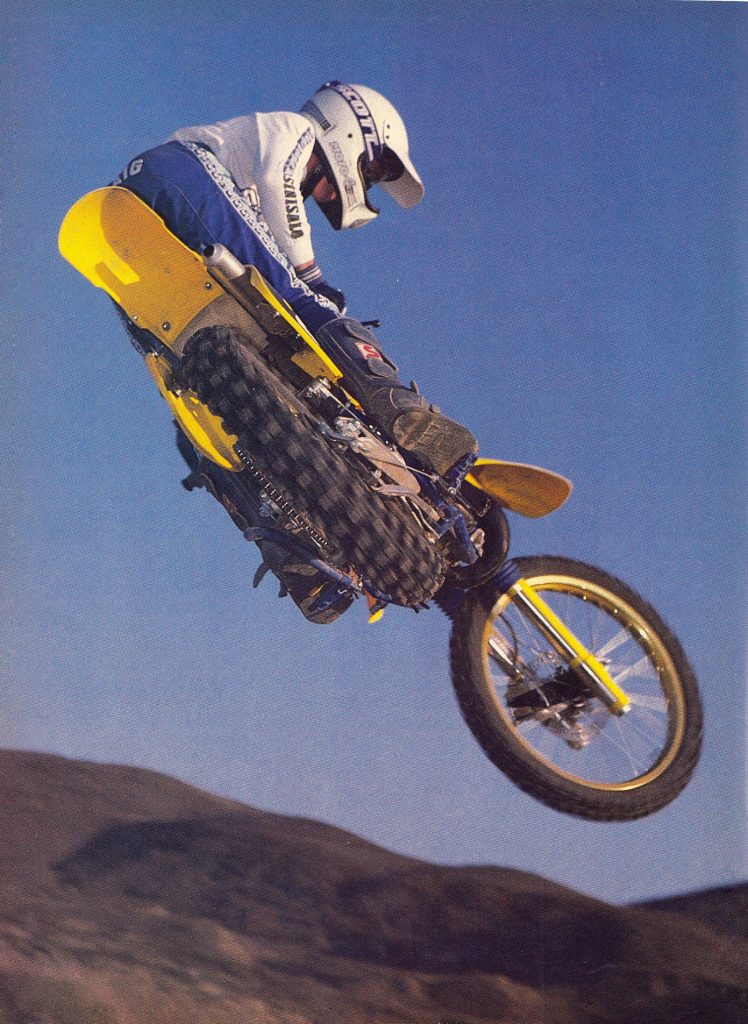

Excellent aerial manners and plush landings made the RM a joy to jump in 1985. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Excellent aerial manners and plush landings made the RM a joy to jump in 1985. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

On the suspension front, the Suzuki was once again the standout of the class. The RM’s unique suspension linkage and all-new damper delivered the most well-sorted ride in the 125 division. Some slower and lighter riders found the Full Floater a bit stiff, but for serious racers, it offered the best combination of comfort and control available from a production 125. Big hits were taken without a complaint and the bike tracked straight and true over sharp curbs and deep G-outs that flummoxed the competition. There was never an unexpected hop or kick from the rear end and the Full Floater could be trusted to keep the RM on its intended path in the rough. With the new level of adjustability, most riders were able to find an acceptable setting without resorting to modification or replacement. The only complaint racers had about the Full Floater in 1985 was the high level of maintenance it required. Its complicated linkage demanded regular servicing to maintain reliable operation and the new super-adjustable shock tended to wear out rather quickly. When fresh, it worked great, but if you neglected its maintenance, its performance deteriorated quickly.

Without a power valve the RM’s old-school Power Reed motor was at a distinct disadvantage in 1985. The motor’s lack of torque and top-end focused powerband seemed to cater to more experienced riders, but its low overall output left most throttle jockeys wanting. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Without a power valve the RM’s old-school Power Reed motor was at a distinct disadvantage in 1985. The motor’s lack of torque and top-end focused powerband seemed to cater to more experienced riders, but its low overall output left most throttle jockeys wanting. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Plush and well-controlled, the RM’s 43mm KYB forks were rated tops in the class in 1985. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Plush and well-controlled, the RM’s 43mm KYB forks were rated tops in the class in 1985. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Up front, the RM’s 43mm KYB forks were once again some of the best available in the 1985 field. The new proportional valve did a good job of smoothing out any mid-stroke harshness and the added adjustability made it easier to dial the forks in for differing skill levels. Really fast guys benefited from stiffer springs, but everyone praised the RM for its smooth damping and plush action. A few riders preferred the Honda’s slightly stiffer settings to the Suzuki’s plushness, but both camps agreed that the red and yellow machines were a cut above the silverware offered on the KX and YZ. For most riders, they were excellent in stock condition, and with a spring swap and some clicker and oil fiddling they were good enough for anyone below a national pro.

The KX125 had plenty of flaws in 1985, but its significant horsepower advantage had most riders picking it as the bike to beat in the 125 class. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The KX125 had plenty of flaws in 1985, but its significant horsepower advantage had most riders picking it as the bike to beat in the 125 class. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the handling department, the RM was surprisingly improved in 1985. Despite not offering any significant geometry changes, the new machine exhibited sharper cornering than the 1984. The combination of the smoother forks and more friendly powerband allowed riders to execute turns with less drama and the front end felt more planted and predictable as a result. It was still not as nimble as the corner-shredding CR, but it could cut a tight line when necessary. Stability continued to be quite good, and the RM never wandered or shook its head violently. Without the “right now” burst of the KX, the RM required more commitment to execute tricky doubles, but it flew well, was nimble feeling in the air, and gobbled up landings. Overall, it was a solid handling machine that got the job done without any sort of flash or drama.

With Mark Barnett (9) moving to Kawasaki, George Holland (27) and Erik Kehoe (16) were Suzuki’s top dogs in the 125 class in 1985. Unfortunately, Suzuki’s dynamic duo was no match for Ron Lechien (6) and his ultra-trick RC125. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With Mark Barnett (9) moving to Kawasaki, George Holland (27) and Erik Kehoe (16) were Suzuki’s top dogs in the 125 class in 1985. Unfortunately, Suzuki’s dynamic duo was no match for Ron Lechien (6) and his ultra-trick RC125. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the detailing front, the RM was still a step behind the best machines in the class in 1985. The new disc brake was an improvement over the old machine’s lackluster drum, but still far behind every other binder in the class. It offered far less bite than the discs found on the competition and was only liked by riders who were not yet comfortable with the abrupt feel of the hydraulic stoppers. The rear drum was more in line with its competitors, and it did a decent job of slowing down the yellow bomber. The revamped motor was not particularly powerful, but it was more reliable than the fragile ’84 had been. The revised metallurgy and reshaped design of the ’85 piston proved much less prone to cracking and with no power valve to service there were fewer parts to worry about getting gummed up or failing. This also made servicing the top end a much simpler affair than on any of the RM’s Japanese competition. If you changed the piston and rings regularly, ran good quality oil, and let it warm up properly when cold, the RM’s motor was as bulletproof as anything in the class.

Swan song: In the last year of its original design, the Full Floater remained the most well-reviewed rear suspension system in motocross. In 1985, nothing in the class was as plush and polished as Suzuki’s collection of struts and rockers. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Swan song: In the last year of its original design, the Full Floater remained the most well-reviewed rear suspension system in motocross. In 1985, nothing in the class was as plush and polished as Suzuki’s collection of struts and rockers. Photo Credit: Suzuki

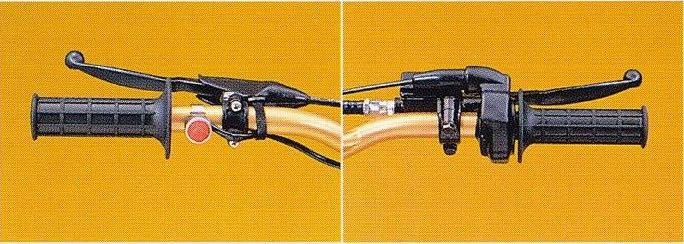

The RM’s grips, bars, and controls were a step behind the best available in the class in 1985. The throttle grip in particular was reviled due to Suzuki’s decision to vulcanize it to the housing. While certainly safer, this made removing the throttle side grip an aggravating and time-consuming ordeal. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The RM’s grips, bars, and controls were a step behind the best available in the class in 1985. The throttle grip in particular was reviled due to Suzuki’s decision to vulcanize it to the housing. While certainly safer, this made removing the throttle side grip an aggravating and time-consuming ordeal. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While most riders approved of the RM’s yellow and blue livery, the same could not be said for its bodywork. Large fitment gaps and odd shapes throughout made the machine seem rather cobby compared to its rivals. The front fender did a decent job of fighting off roost from the front wheel, but its peculiar duck-billed shape was polarizing to many. The shape of the seat was also panned for its propensity to lock the rider in one position. Its banana shape pushed the rider forward to the base of the tank and made it difficult to stand or slide rearward once you were trapped in its pocket. Smaller riders did appreciate the RM’s low seat height but anyone over 5’10” was likely to find Suzuki’s 125 a bit cramped. Long-time Suzuki pilots had fewer gripes with the RM’s layout, but a quick comparison with Honda’s all-new CR125R had many testers commenting that the yellow machine felt like it was stuck in 1982.

The RM’s narrow stock footpegs were par for the course in 1985. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The RM’s narrow stock footpegs were par for the course in 1985. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Flimsy steel bars, fragile levers, and a butter-soft chain and sprocket set were also on the RM’s dance card for 1985. This was standard fare for a Japanese 125 at the time, but the RM’s components seemed poor even by the rather low-class standards of the time. The odd assortment of bolt sizes chosen by the engineers and their over-affection for Phillips screws also made working on the RM more tedious than it should have been. Stripped screws, rounded fasteners, and cracked mounting brackets were all common problems for RM owners in 1985. The stock grips were also an absolute nightmare to replace due to Suzuki’s liability-conscious decision to vulcanize the throttle grip directly to the housing. Because of this, it was necessary to replace the throttle housing with an aftermarket alternative or spend hours hacking away with a razor blade if you wanted to swap out your grips. Ugh…

In 1985, Suzuki once again dominated the suspension category but forgot to bring the heat in the department that most mattered to the majority of 125 pilots. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1985, Suzuki once again dominated the suspension category but forgot to bring the heat in the department that most mattered to the majority of 125 pilots. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In the end, the 1985 RM125 did not turn out to be the machine to lead Suzuki back to the 125 promised land. Even with solid handling and the best suspension in the class, the RM was forced to play catchup once again. Its lack of firepower in the motor department was just too much to overcome in a division ruled by pony prowess. With some motor work and a committed pilot, the RM could be a winner, but in stock condition, it was handicapped in the one place that hurt it the worst.