For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s all-new CR125R for 1998.

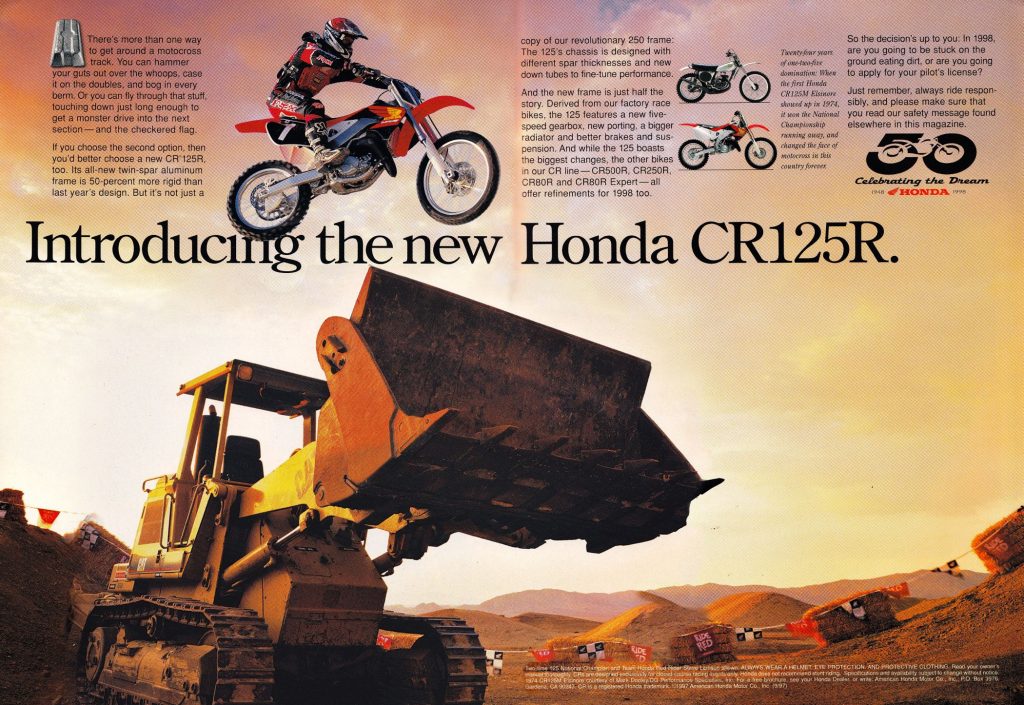

All-new from the ground up, the 1998 CR125R was Honda’s first attempt at bringing an aluminum chassis to their 125 platform. Photo Credit: Honda

All-new from the ground up, the 1998 CR125R was Honda’s first attempt at bringing an aluminum chassis to their 125 platform. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1997, Honda set the motocross world abuzz with the introduction of the industry’s first aluminum-framed production motocross machine. The all-new ’97 CR250R debuted to mountains of excitement and glowing reviews. Magazine editors raved about its spacy looks and blistering motor performance and racers snapped up the alloy-framed wonder in droves. Hype, sexy styling, and Honda’s impeccable racing reputation all contributed to delivering Big Red a massive showroom hit in 1997.

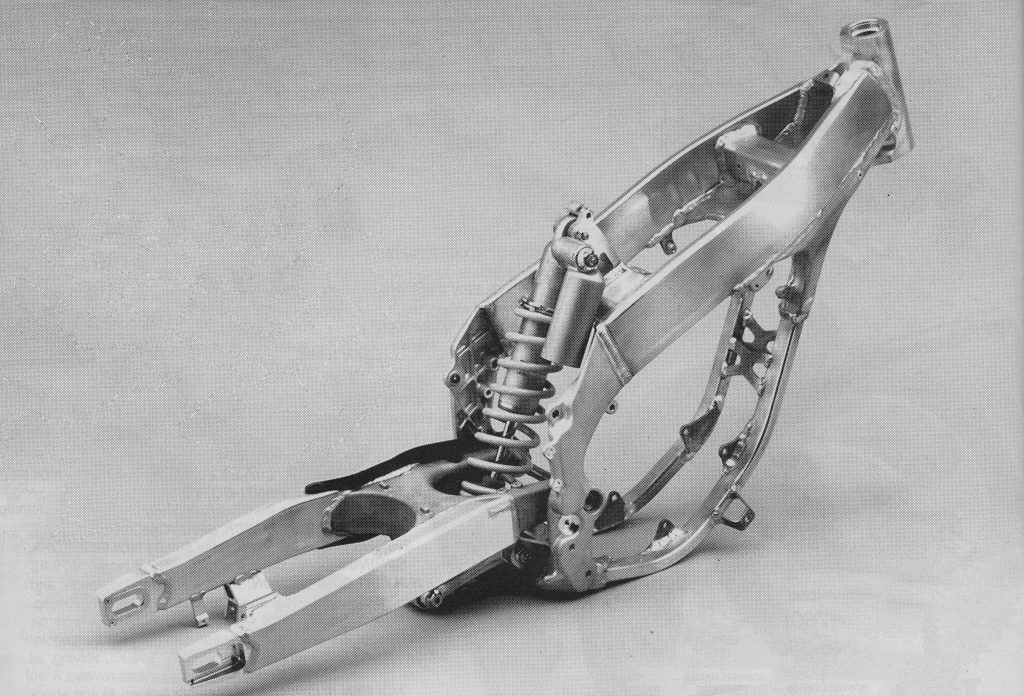

Introduced in 1997 on their CR250R and crafted out of 7000 Series aluminum, the CR125R’s innovative twin-spar alloy design promised greater strength and increased rigidity over a traditional steel-framed design. Photo Credit: Honda

Introduced in 1997 on their CR250R and crafted out of 7000 Series aluminum, the CR125R’s innovative twin-spar alloy design promised greater strength and increased rigidity over a traditional steel-framed design. Photo Credit: Honda

While the new CR250R was a big hit in terms of sales, it turned out to have a more mixed reception on the track. Fears in Japan over potential failures led to an overbuilt frame that hindered the CR’s handling and comfort. Excessive vibration, mediocre steering precision, and an overly harsh feel were all hallmarks of this first-generation alloy frame. The CR250R continued its reputation for impeccable motor performance, but its handling and comfort both took major steps back in the transition to the all-new design.

While not quite as hyped as the CR250R the year before, the move to aluminum on the CR125R was big news in 1998. Photo Credit: Honda

While not quite as hyped as the CR250R the year before, the move to aluminum on the CR125R was big news in 1998. Photo Credit: Honda

While the CR250R was garnering mountains of press in 1997, its little brother soldiered on largely unchanged aside from some motor tweaks and a fork upgrade. All-new in 1993, the CR125R’s platform was beloved for its sharp turning and blistering top-end performance. Its HPP motor revved harder and higher than anything else in the class and the CR was recognized as the top choice for fast kids and aspiring national pros.

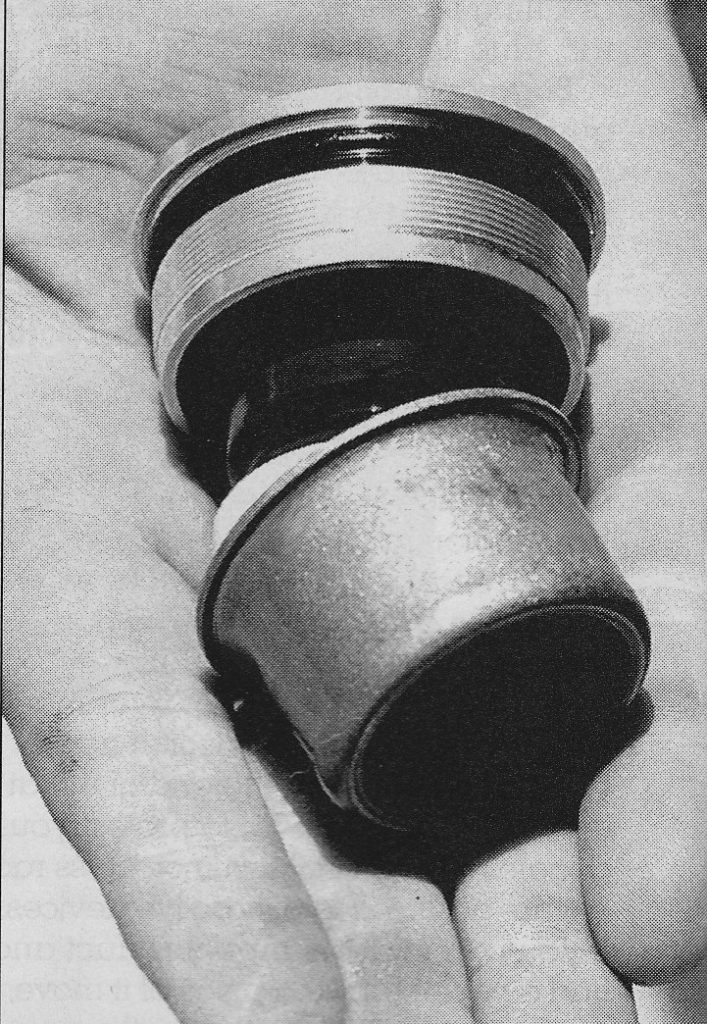

All-new Kayaba forks for 1998 added elastomer bumpers to improve bottoming feel when using full travel. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

All-new Kayaba forks for 1998 added elastomer bumpers to improve bottoming feel when using full travel. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the CR125R was without peer at the upper end of the rpm range, its 125cc power plant was not always the top choice for riders of every skill level. Low-end torque was virtually non-existent, and the bike demanded skill and commitment to keep it in the meat of its power. The little Honda’s suspension was also often less refined than its rivals with machines like Suzuki’s RM125 frequently besting it in shootouts due to its more flexible motor characteristics and superior suspension.

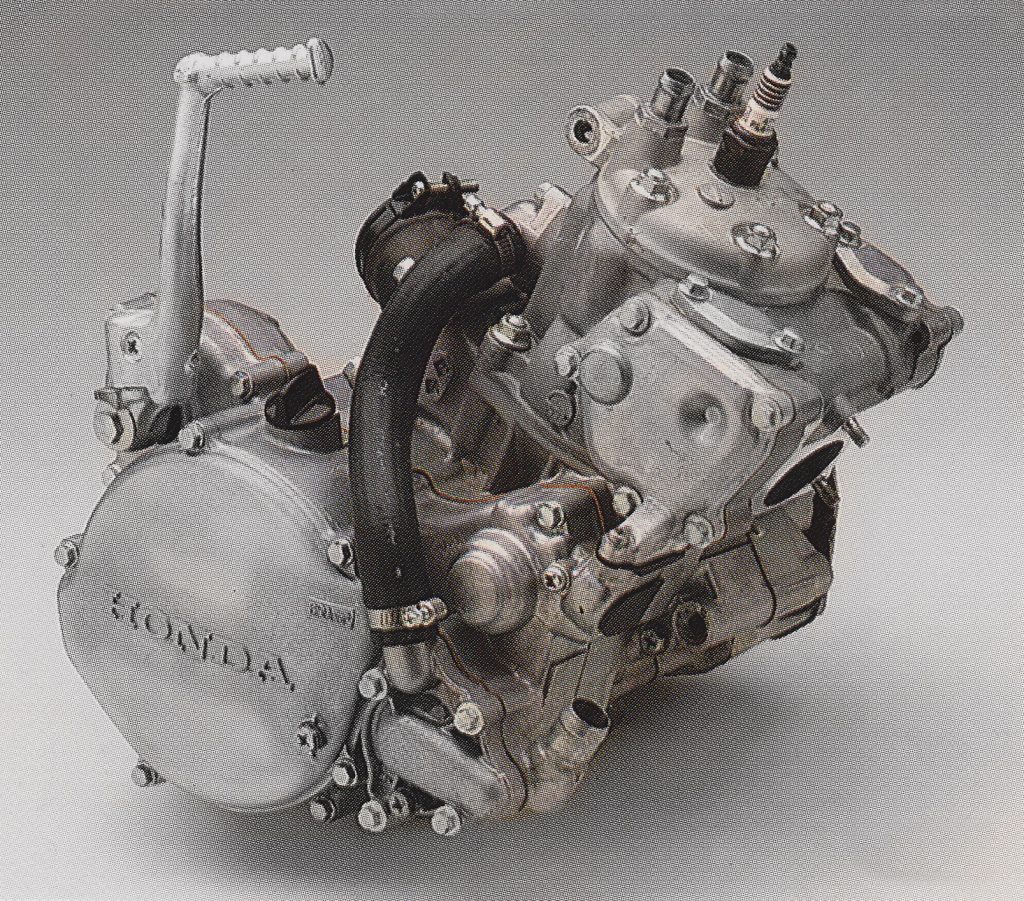

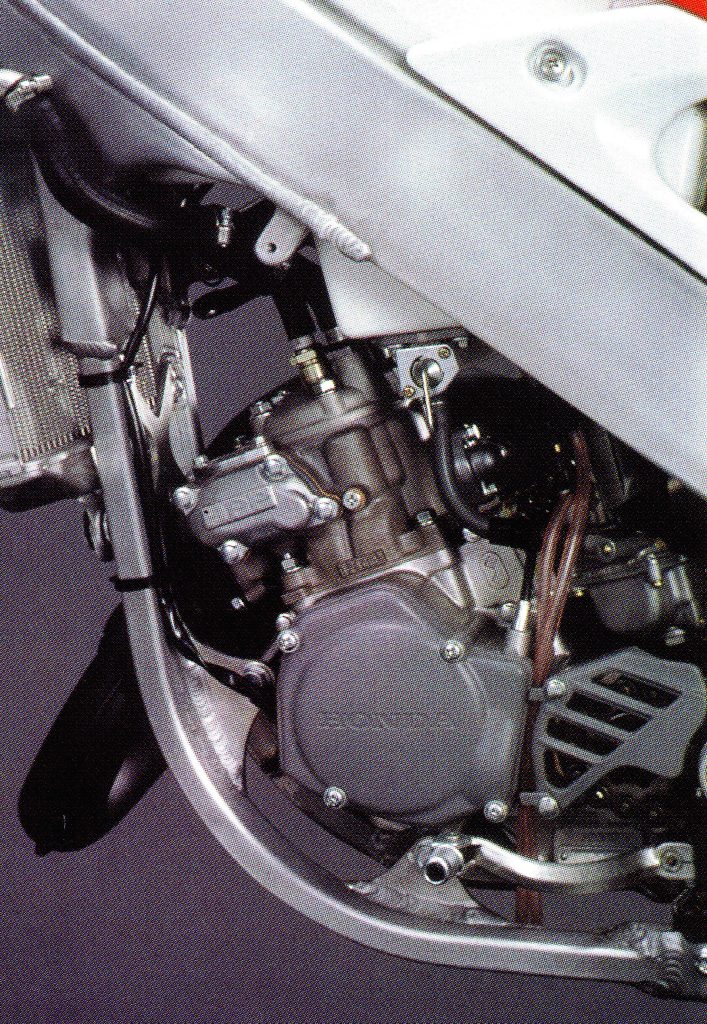

Largely unchanged since 1990, Honda’s proven 124cc powerhouse received several significant updates in 1998. An all-new cylinder and ignition looked to boost low-end power while a redesigned transmission eliminated the sixth gear for improved durability. Photo Credit: Honda

Largely unchanged since 1990, Honda’s proven 124cc powerhouse received several significant updates in 1998. An all-new cylinder and ignition looked to boost low-end power while a redesigned transmission eliminated the sixth gear for improved durability. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1997, it was Yamaha’s deep blue YZ125 that conquered the 125 wars with an incredibly broad and brawny powerband. After a decade of mediocre YZ125s, the blue crew came out swinging in the mid-nineties with a string of powerhouse 125s. The 1997 YZ125 felt like a 175 compared to its rivals and every magazine praised its potent power and excellent do-it-all chassis.

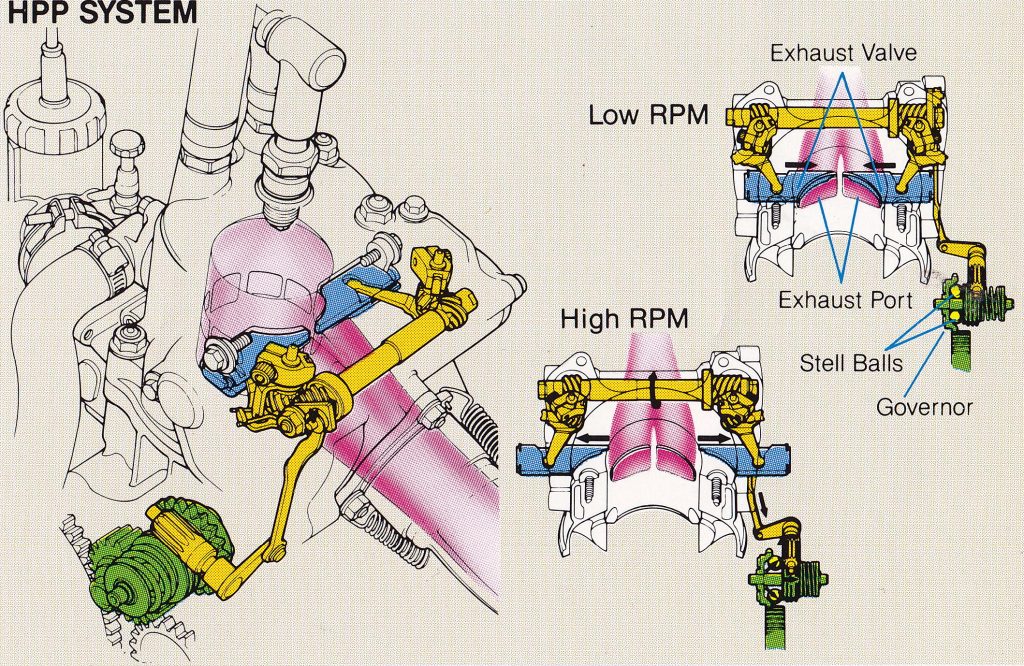

Introduced in 1990 on the CR125R, Honda’s Power Port system was renowned for its blistering top-end performance and reviled for its complicated and maintenance-intensive design. Photo Credit: Honda

Introduced in 1990 on the CR125R, Honda’s Power Port system was renowned for its blistering top-end performance and reviled for its complicated and maintenance-intensive design. Photo Credit: Honda

While the ’97 YZ was a unanimous choice as the top 125 in the land, the CR125 still had a loyal following among those with the skill to put its peaky power to good use. The little Honda still had the longest top-end pull, strongest brakes, best clutch, smoothest shifting, and most bulletproof motor. Its chassis lacked the curb appeal of its sexy alloy brother, but it was a decent handler with suspension that was raceable and an impeccable reputation for quality and reliability. Pros still loved its potent performance and most riders felt it was the second-best 125 available in 1997.

While very similar to the CR250R in appearance, the CR125R’s frame was unique to the smaller machine with thinner-walled construction and a 15% reduction in overall chassis stiffness. Photo Credit: Honda

While very similar to the CR250R in appearance, the CR125R’s frame was unique to the smaller machine with thinner-walled construction and a 15% reduction in overall chassis stiffness. Photo Credit: Honda

After a season of minor updates in 1997, it was time for a complete revamp of the CR125R platform in 1998. First up and most noticeable was the retirement of the old machine’s proven steel frame in favor of an all-new alloy design. Similar in design to the 1997 CR250R’s chassis, the new frame was crafted out of 7000-Series aluminum and featured two large spars arrayed in a perimeter fashion as its main structural backbone. The 1998 CR250 and CR125 frames looked very similar, but the 125’s chassis featured thinner-walled construction, unique geometry, and a smaller engine cradle that ran closer to the engine cases. A new welding process, reshaped downtubes, and thinner-walled construction addressed some of the alloy chassis complaints from ’97 by reducing chassis rigidity by 15% when compared to the 1997 CR250R. Contrasted to the 1997 CR125R’s steel frame, the new aluminum design was 50% more rigid and featured a steeper geometry for improved turning. Both the 1998 CR250R and CR125R shared the same bodywork, handlebars, gas tank, alloy subframe, rear suspension linkage, swingarm, and rear axle for 1998. Braking was improved for 1998 with the addition of a larger 240mm rotor for the rear and a redesigned brake pedal designed to reduce flex.

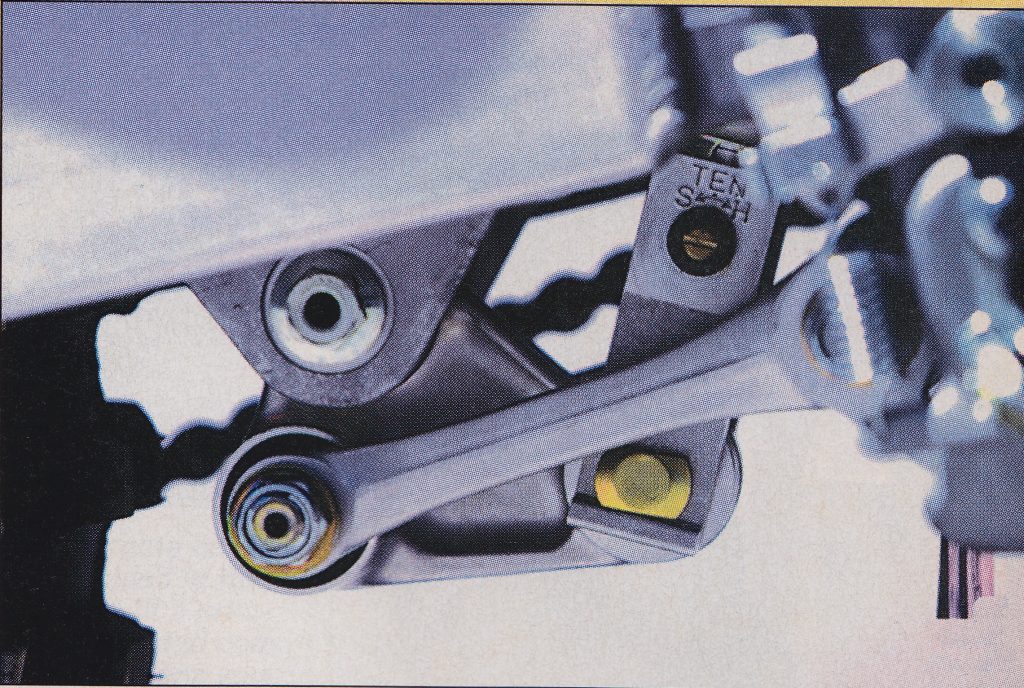

An all-new linkage for 1998 offered a flatter ratio and less leverage at full travel. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

An all-new linkage for 1998 offered a flatter ratio and less leverage at full travel. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the suspension front the CR125R received an all-new fork and shock combination for 1998. Up front, the CR employed an updated version of the 46mm Kayaba forks first utilized in 1996. The new forks featured revised damping and a redesigned bottoming system with small rubber bumpers at the top to reduce harshness and hydraulic lock under full travel. In the rear, the CR received an all-new Kayaba shock designed to pair with its redesigned linkage which featured a flatter ratio than 1997. The new damper offered 12.7 inches of rear travel with separate external adjustments for high and low speed compression as well as rebound damping control.

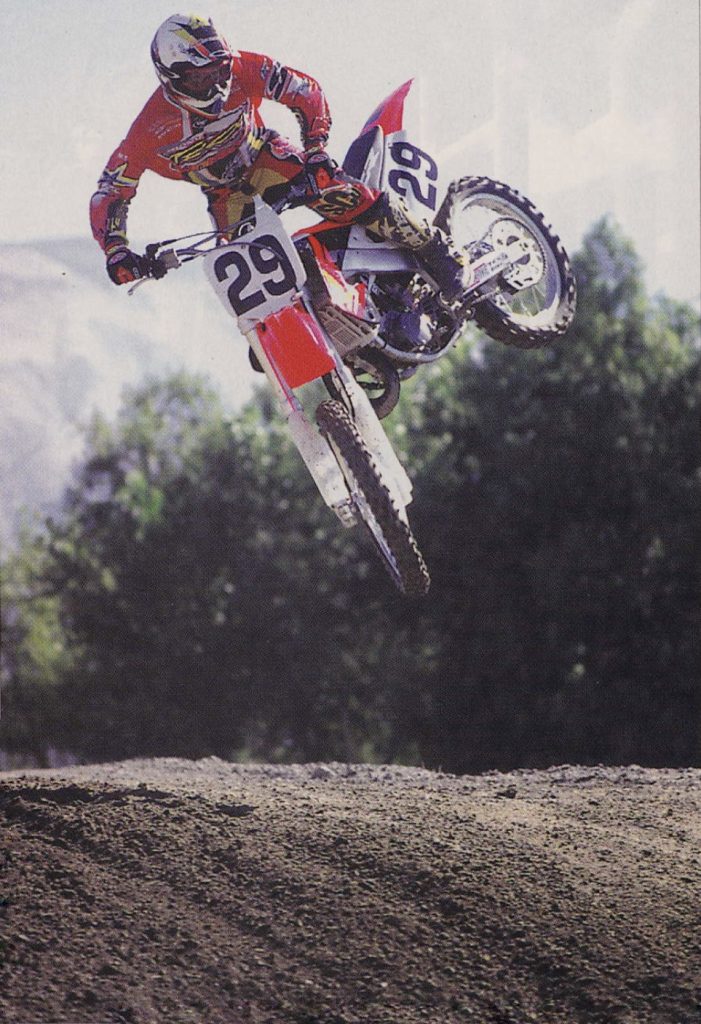

FMF was brought on in 1998 as an additional satellite team to campaign the all-new CR125R. David Pingree would take the CR to 5th overall in the 1998 West Coast Supercross standings. Photo Credit: N-Style

FMF was brought on in 1998 as an additional satellite team to campaign the all-new CR125R. David Pingree would take the CR to 5th overall in the 1998 West Coast Supercross standings. Photo Credit: N-Style

On the motor front, the CR continued to employ the same Honda Power Port (HPP) variable exhaust valve system it had used since 1990. In 1992, the CR250R retired the HPP and moved to a more advanced system that both varied exhaust port shape and altered exhaust volume to provide the best combination of broad power and high-RPM performance. Pioneered by Kawasaki with the KIPS, this combination of features was found to deliver the best overall performance in a two-stroke machine. While the HPP design delivered blistering top-end performance, it had never been able to replicate the snappy low-end response of many of its 125 competitors.

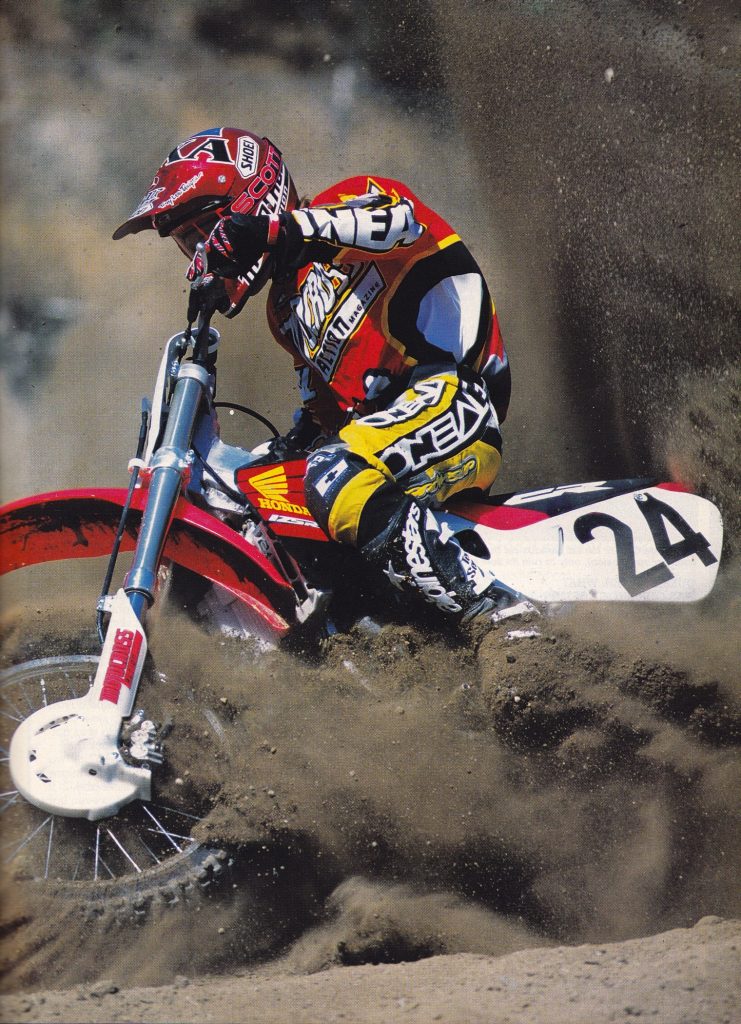

Big power was not on the Honda’s menu for 1998 but the bike was quick over a narrow spread in the midrange. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Big power was not on the Honda’s menu for 1998 but the bike was quick over a narrow spread in the midrange. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1998, Honda looked to boost the motor’s flexibility by making several changes to both the top and bottom end. A new cylinder was spec’d with all-new porting and reshaped exhaust valves. Both the transfer and exhaust ports were massaged with new guides added to the exhaust valves for more precise operation. The reed valve received a new stopper and the ignition was revamped to produce double the output of 1997. An all-new airbox was added to work with the redesigned frame and a new single radiator replaced the dual units of 1997. The new radiator carried 18% more fluid and was claimed to be 22% more efficient in Honda’s testing. Mixing duties continued to be handled by Keihin’s proven 36mm flat-slide PJ carburetor. Interestingly, the CR125R’s carburetor did not receive the CR250R’s Powerjet for 1998.

After 11 years of top-end screamers, Honda delivered a disappointing dud in 1998. The new motor looked the same but ran completely different. All of its power was delivered over a narrow spread in the midrange with very little potency above or below this burst. Photo Credit: Honda

After 11 years of top-end screamers, Honda delivered a disappointing dud in 1998. The new motor looked the same but ran completely different. All of its power was delivered over a narrow spread in the midrange with very little potency above or below this burst. Photo Credit: Honda

In the bottom end, Honda made a significant change by dropping the sixth gear and moving to a five-speed gearbox for 1998. The new transmission featured wider and stronger gears and all-new ratios designed to complement the revised power characteristics. Honda claimed the new arrangement was both lighter and stronger than the old six-speed design. The clutch mechanism remained unchanged, but a new stainless-steel cable was added for smoother operation.

Steve Lamson was Honda’s top gun on the CR125R in 1998. Unfortunately, aside from a win at Hangtown, he was unable to rekindle the winning ways of his two 125 National Championship seasons. Photo Credit: Donn Maeda

Steve Lamson was Honda’s top gun on the CR125R in 1998. Unfortunately, aside from a win at Hangtown, he was unable to rekindle the winning ways of his two 125 National Championship seasons. Photo Credit: Donn Maeda

On the track, the all-new CR125R offered a completely different riding experience than previous Honda 125s. The new frame and layout gave the machine a larger 250 feel that some riders liked, and others did not. The twin-spar frame was very wide through the middle with a tall, hard, and flat seat that imparted a “sit on” feel very unlike previous CR125Rs. Despite the 15% reduction in rigidity, the alloy frame continued to feel very harsh and unforgiving. Vibration from the motor and feedback from the suspension made it directly back to the rider – both of which contributed to premature rider fatigue. As it had with the CR250R, the new alloy chassis seemed to neuter some of the previous machine’s handling precision. Despite its steeper geometry, the new chassis exhibited a front-end push that was previously unheard of on a Honda 125. The front end never felt fully planted and the machine seemed to skate above the track instead of biting into it. If there was a berm or something to push against it turned well enough, but if the track was hard and flat the bike took more effort than its rivals to hug the inside line. High-speed action remained a white-knuckle affair with epically unnerving headshake manifesting itself under deceleration. With its large feel, the CR was less nimble in the air than machines like the RM125, but it jumped straight and generally went where it was pointed. In large whoops the chassis’ stiffness could be felt, and the machine was rock solid in stadium rockers. Most average riders did not seem to feel the need for this level of rigidity, but pros did appreciate its ultra-stiff character when pushing the machine’s limits.

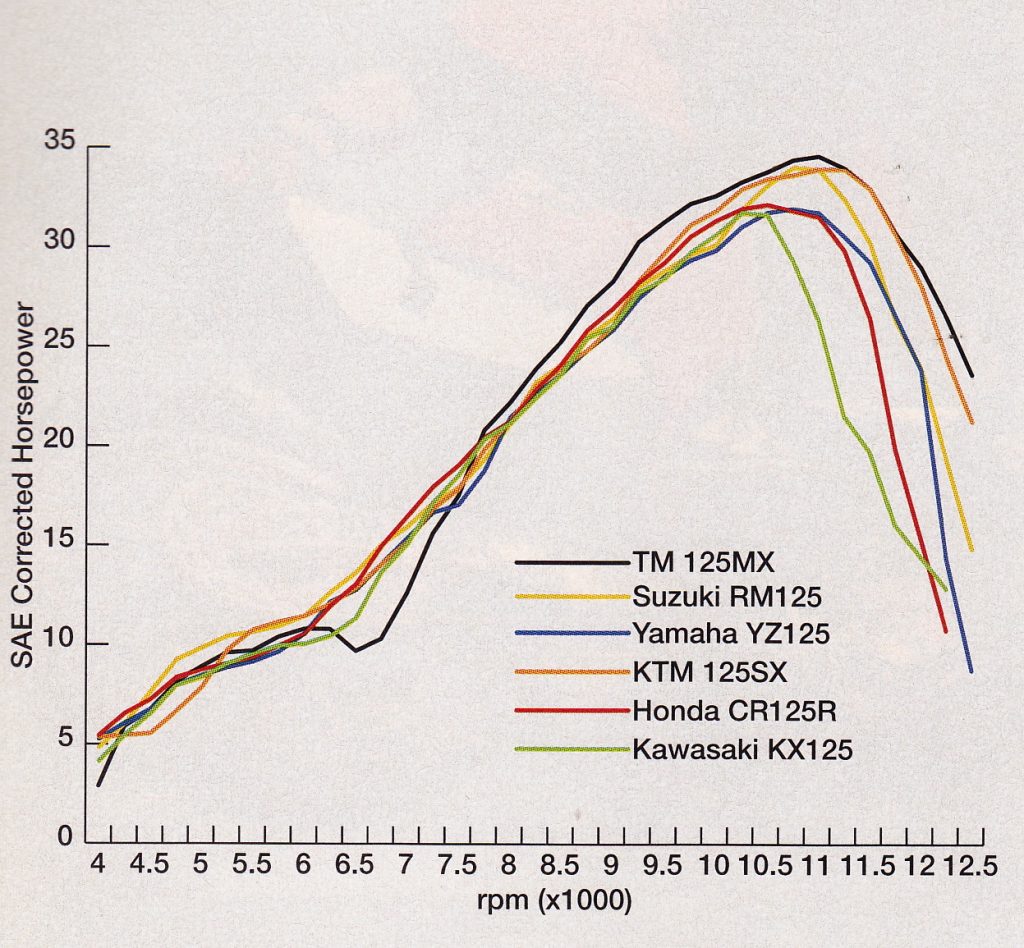

This dyno chart tells the tale of the tape in 1998. Aside from a small blip in the midrange, the CR gets dominated by every machine but the woefully underpowered KX125 throughout the rest of its power curve. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

This dyno chart tells the tale of the tape in 1998. Aside from a small blip in the midrange, the CR gets dominated by every machine but the woefully underpowered KX125 throughout the rest of its power curve. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The new 46mm “bumper” forks delivered a middling performance in 1998. Fast riders felt they were too soft and slow riders found their midstroke harshness off-putting. While raceable in stock condition, there were far better-sorted front ends available in 1998. Photo Credit: Honda

The new 46mm “bumper” forks delivered a middling performance in 1998. Fast riders felt they were too soft and slow riders found their midstroke harshness off-putting. While raceable in stock condition, there were far better-sorted front ends available in 1998. Photo Credit: Honda

The other half of the CR’s handling equation for 1998 was the performance of its new suspension. Here, the frame once again played a part by transmitting a great deal of feedback to the rider. Fork performance was improved, but the CR continued to trail most of its rivals in comfort. The nearly identical Kayaba “bumper” forks found on the 1998 YZ125 delivered a much plusher ride and some of this was probably due to the harsh feel of the CR’s frame. Overall damping was lightened for 1998 with settings that were designed to provide more linear performance, but the forks continued to exhibit a harsh spike in the midstroke. The bottoming feel was improved with the new elastomer bumpers, but the forks were felt to be too prone to bottoming by many. Faster and heavier riders were likely to need heavier springs and maybe a revalve, but the forks could be raced in stock condition with a little fine-tuning.

Out back, the new Kayaba shock suffered from the same “dead” feeling the CR250R had struggled with in 1997. Big hits were taken well but the shock banged and thudded through bumps that other machines floated over with ease. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Out back, the new Kayaba shock suffered from the same “dead” feeling the CR250R had struggled with in 1997. Big hits were taken well but the shock banged and thudded through bumps that other machines floated over with ease. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the rear, the new shock was even less loved with a harsh feel that was only exacerbated by the CR’s hard and thin seat. Square-edged bumps and sharp ledges were transmitted directly to the rider’s kidneys with a dull “thump” that rattled teeth and bruised backsides. As on the 250, the new alloy frame and linkage imparted a “dead” feel to the rear suspension that seemed to cause the machine to pound into bumps that the other machines floated over. This worked well in big whoops where the CR could be trusted to hammer through without doing anything unexpected, but the bike was harsh nearly everywhere else. Big jumps were not a problem, but rear comfort was well below what most non-pros considered acceptable. If you were a hard charger, the shock worked well, but for everyone else, there were better performers available in 1998.

The new chassis provided a very solid feel, but the CR was no longer the nimble handler many had come to expect from Big Red. Front-end traction was suspect and the machine required far more commitment to change direction than in the past. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The new chassis provided a very solid feel, but the CR was no longer the nimble handler many had come to expect from Big Red. Front-end traction was suspect and the machine required far more commitment to change direction than in the past. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Of all the changes made in 1998, by far the most surprising was the performance of the CR125R’s motor. For over a decade, the CR125R was the king of high-RPM screamers and that string finally ended in 1998. Considering the modest nature of the motor changes made for 1998, this was quite a shock to many. Anyone who had ridden the 1997 CR250R was not surprised by the handling and suspension compromises the new chassis demanded, but no one in their wildest dreams predicted that the new CR125R would be slow. The 250 had remained a rocket in its transition to aluminum, but something went wrong when they shoehorned the smaller motor into the new chassis. At the time, many speculated that the new airbox and airboot were the culprit, but tuners would later blame the new cylinders for much of the CR125R’s newly found power woes. Regardless of the root cause, the new cylinder, airbox, reeds, and ignition combined to produce a powerplant that was a mere shadow of its former self.

While the motor lacked the boost of previous red rockets, the CR remained a capable flyer. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the motor lacked the boost of previous red rockets, the CR remained a capable flyer. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the track, the revamped 124cc motor was incredibly difficult to ride with a one-dimensional power curve that came on late and signed off early. Low-end torque was virtually non-existent, and the bike was a bottomless pit of bog below the midrange. Once into the midrange, the Honda snapped to attention and pumped out a strong blast of power that rocketed the bike forward. Unfortunately, however, this blast ended just as fast as it started, and the bike refused to pull past the midrange. Just as the old bike was getting started, this new version decided to throw in the towel. For riders accustomed to 11 years of Honda screamers, this new power profile was something of a shock. The revamped powerband was closer in feel to an early nineties Yamaha and utterly unlike anything Honda had produced since the early 1980s. Early testers thought something had to be wrong, but the CR’s power turned out to be difficult to recapture. Throwing on a pipe, rejetting the carb, and opening up the airbox helped a bit, but the new motor refused to run anything like the powerplants of old.

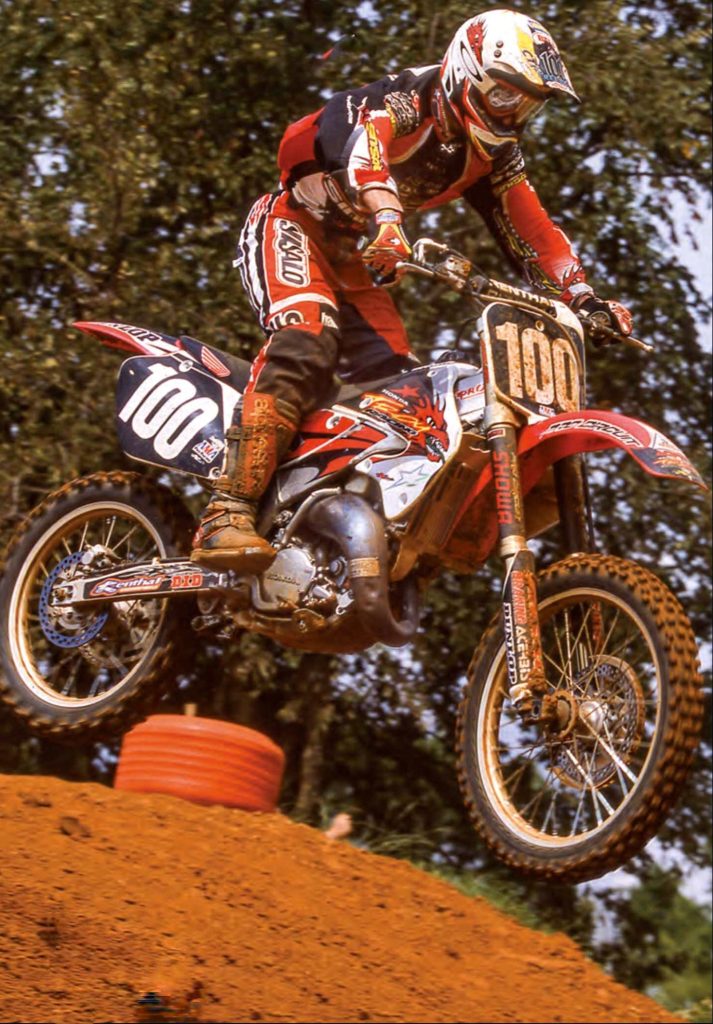

Mike Brown made a return to US racing on the all-new CR in 1998 riding for Phil Alderton’s powerful Honda of Troy race team. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

Mike Brown made a return to US racing on the all-new CR in 1998 riding for Phil Alderton’s powerful Honda of Troy race team. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

This new powerband exasperated novices with its peaky nature and frustrated pros with its lack of top-end pull. If ridden correctly, its midrange motor was decently fast, but it was hard to keep it from bogging out of turns or running flat if revved too far. Jetting continued to be a point of frustration as well with the Honda proving very sensitive to temperature and humidity changes. Also adding to the motor’s frustrating nature was its new five-speed transmission which seemed to be geared for the low-end torque that never materialized. With the stock final drive in place, the bike often felt between gears and even skilled riders had a difficult time keeping the bike on the bubble. Most riders felt adding a tooth to the rear and mercilessly abusing the clutch were the best ways to get the most out of its narrow power curve. While the clutch was largely up to this abuse, the new transmission proved less so with some riders experiencing unintended shifts under power. This propensity to pop into the next gear under power was unheard of on a Honda and was traced to issues with the shift drum and detent mechanism. Thankfully, this issue did not seem to be widespread, and the bike never popped into a false neutral.

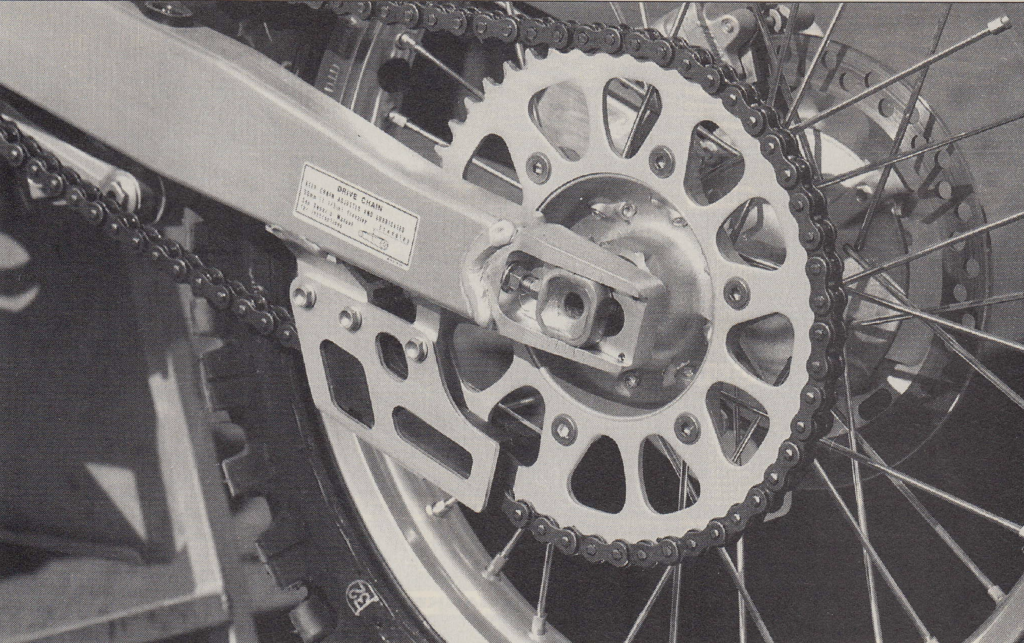

With its five-speed transmission and narrow powerband, many riders felt the CR benefited from a larger rear sprocket in 1998. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With its five-speed transmission and narrow powerband, many riders felt the CR benefited from a larger rear sprocket in 1998. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the detailing front, the all-new CR was a work of art in many areas and a bit head-scratching in others. All the materials from the high-quality bolts, to the forged levers, to the comfortable and durable grips were top-notch. The brakes offered fantastic power and feel and never seemed to require bleeding. The steel bars were well-shaped, durable, and less prone to bending than the competition. All the plastic looked great, fit perfectly, and took abuse well. The alloy frame was incredibly trick with its beautiful welds and exotic looks and it stayed looking new far longer than the painted competition. In terms of durability, the new frame was also quite robust, with failures being no more common than the steel units it replaced. While the frame looked cool, its design did make access to some things more difficult and more than a few riders experienced an odd sticking of the triple clamp to the frame at full lock. The sharp edge of the frame could dig into the lower clamp at full lock and cause the two to stick together. Because this was not something you wanted to happen it was a good idea to add a slight chamfer to the leading edge of the frame where the two contacted to prevent an unintended clicker. The ignition cover was also made of flimsy plastic that was easily warped or damaged. If you tightened the screws too tight, it deformed and would let mud and water in where it did not belong. Replacing this with an aftermarket unit was cheap insurance against a costly repair down the line. The vibration was a constant annoyance as the alloy frame seemed to channel it all right to the rider’s hands. Switching to rubber-mounted clamps and an aluminum bar seemed to help but the tingle never fully went away.

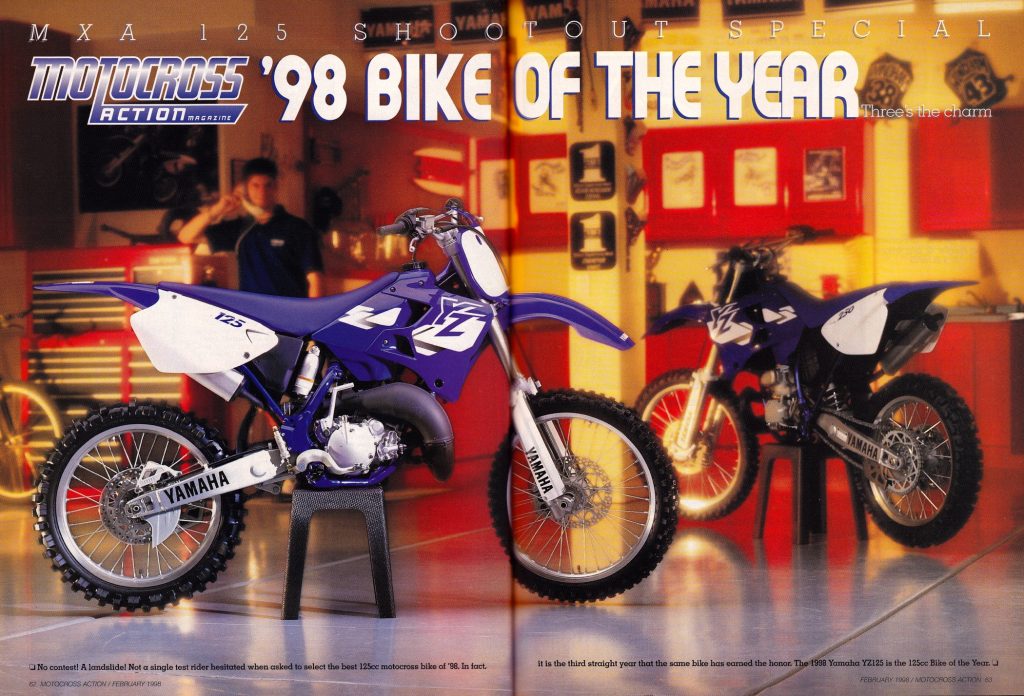

Yamaha’s YZ125 had the competition covered in 1998. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Yamaha’s YZ125 had the competition covered in 1998. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The rest of the motor, while not particularly powerful, was at least reliable. Top-end life was good, and the bike took abuse well as long as you cleaned the air filter regularly, used good quality oil (Honda recommended full synthetic), and stayed on top of HPP maintenance. If you did neglect the valves, the HPP could become sticky and further add to your horsepower woes. Servicing them continued to be a real pain in the kidney belt and no one much cared for their complicated design. With its narrow powerband, clutch abuse was a must, and this tended to foul the transmission fluid with aluminum from the drive plates rather quickly. Changing this fluid regularly was a must if you wanted to keep the clutch and transmission healthy. While the ghost shifting was an annoyance for the few who experienced it, the problem did not seem to hinder reliability. No one reported the type of blown gear sets that plagued YZ owners the year before.

Pretty to look at but disappointing on the track, the 1998 CR125R signaled the end of the line for Honda’s era of 125 motor success. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Pretty to look at but disappointing on the track, the 1998 CR125R signaled the end of the line for Honda’s era of 125 motor success. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the end, the 1998 Honda CR125R turned out to be one of the most surprising disappointments of the decade. The mixed reaction its bigger brother received in 1997 certainly tamped down some of the enthusiasm around its switch to aluminum, but no Honda fan in their wildest dreams would have predicted the new bike would be slow. Overly stiff and poorly suspended? Sure, but slow? No way. This revelation was a shock to those who had come to expect a certain type of 125 performance from Big Red. Beautifully built and artfully styled, the 1998 Honda CR125 was a machine with tons of sex appeal but little substance. Stiff, slow, and outclassed by its rivals, the CR’s days as king of the 125 rev rangers had finally come to an end.