For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at KTM’s ground-pounding 2000 520 SX.

KTM’s all-new 520SX represented the first real competition for Yamaha’s revolutionary YZF four-stroke. Photo Credit: KTM

KTM’s all-new 520SX represented the first real competition for Yamaha’s revolutionary YZF four-stroke. Photo Credit: KTM

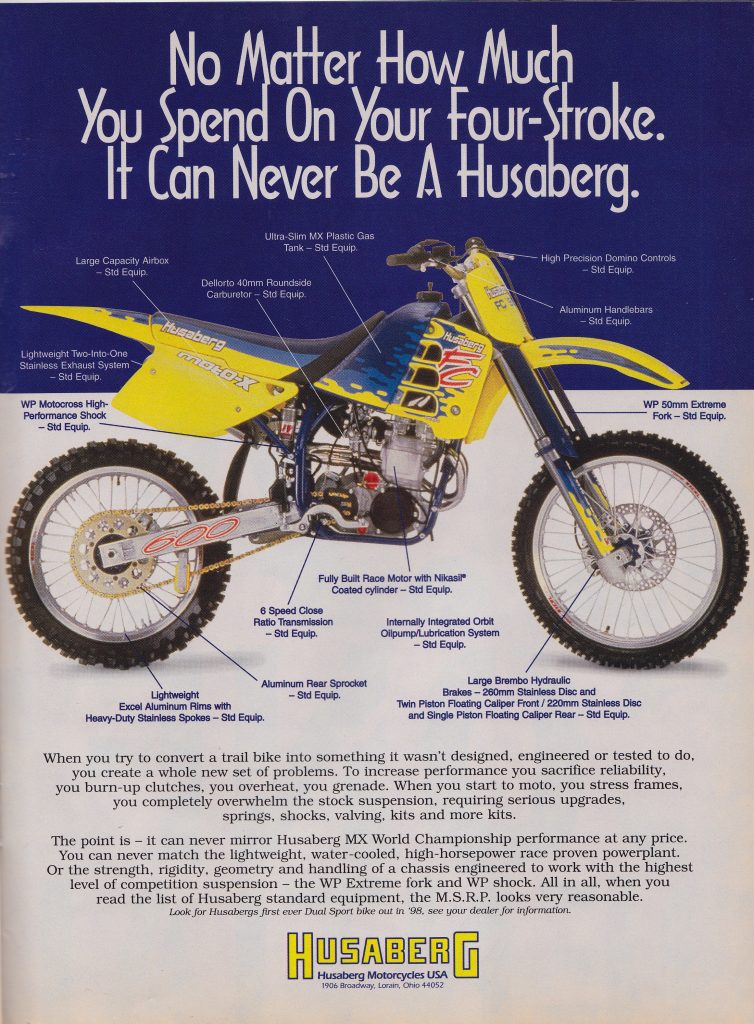

In 1998, Yamaha kicked off the modern racing four-stroke revolution with the introduction of their game-changing YZ400F. Part YZ250 and part FZR600 sport bike, the original YZ400F was an absolute revelation in rideability, reliability, and performance. At the time of the YZ400F’s introduction, most racers considered four-strokes to be off-road playthings or European curiosities. Converted XRs, DRs, and KLXs did battle with Husabergs, VORs, ATKs, and the occasional Husqvarna for the hard-earned cash of the four-stroke enthusiasts. These machines often delivered impressive performance, but their weight, cost, and quirky nature prevented them from being anything more than a sideshow to the two-stroke main attraction.

KTM’s acquisition of Husaberg in 1995 provided the Austrians with a valuable wealth of knowledge when it came time to develop a competitor to Yamaha’s YZ400F. Photo Credit: Husaberg

KTM’s acquisition of Husaberg in 1995 provided the Austrians with a valuable wealth of knowledge when it came time to develop a competitor to Yamaha’s YZ400F. Photo Credit: Husaberg

With the introduction of the 1998 YZ400F, however, Yamaha changed this paradigm completely. The Yamaha thumper was affordable, reliable, and incredibly easy to ride. Right out of the crate, the YZ400F was competitive with any two-stroke available and much better than most. Its combination of excellent handling, smooth power, and Japanese refinement won over riders who had previously scoffed at the idea of a truly competitive four-stroke motocrosser. Overnight, the four-stroke became cool again.

The 520’s new frame was based largely on the design of the two-stroke 250SX. Both frames shared the same basic dimensions aside from modifications needed to accommodate the larger four-stroke motor. Photo Credit: KTM

The 520’s new frame was based largely on the design of the two-stroke 250SX. Both frames shared the same basic dimensions aside from modifications needed to accommodate the larger four-stroke motor. Photo Credit: KTM

Back in Japan, the success of the works YZM400F and its production counterpart took the rest of the motocross industry completely by surprise. None of Yamaha’s Big Four competitors even had a prototype in the works and this left the field completely open as Yamaha converted thousands of four-stroke skeptics into valve-and-cam true believers.

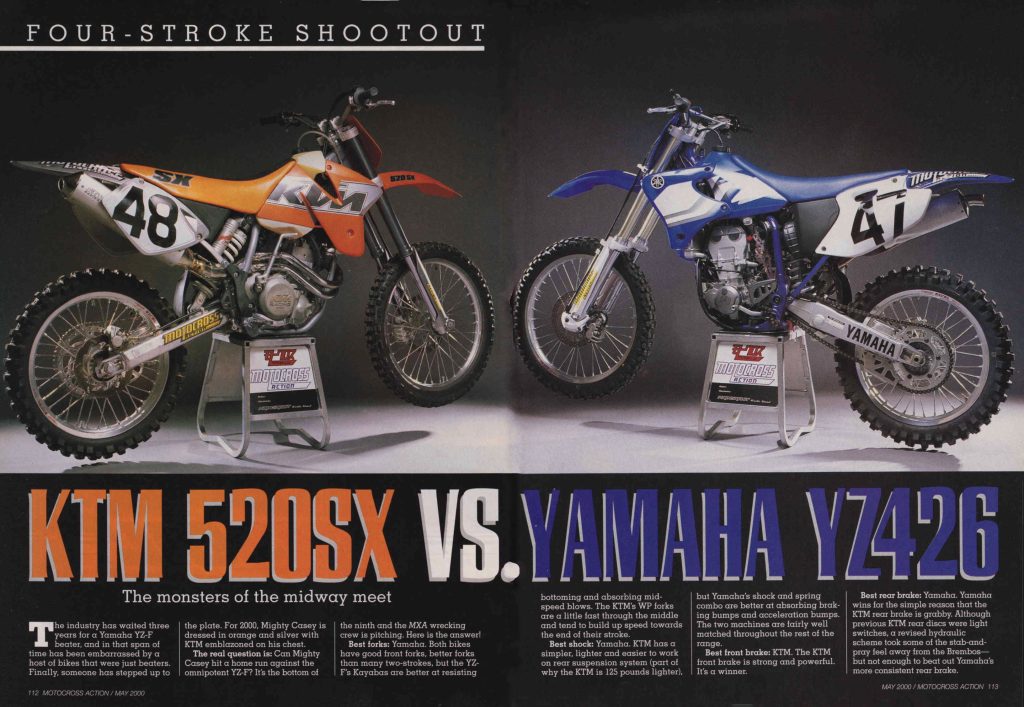

The showdown between KTM’s 520SX and Yamaha’s all-new YZ426F was one of the most anticipated battles of Y2K. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The showdown between KTM’s 520SX and Yamaha’s all-new YZ426F was one of the most anticipated battles of Y2K. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Over in Europe, the landscape was slightly different with the four-stroke sharing much of the spotlight in the Open class division. With Japan abandoning the 500s in the early nineties, European firms Husaberg, Vertemati (VOR), and Husqvarna were quick to fill that void. Riders like Joël Smets, Jacky Martens, and Peter Johansson took the big booming thumpers to victory against the aging Japanese two-stroke machines. While these European big bores proved very capable on the track, they remained more of a novelty than a mainstream product. Limited dealer networks, cobby construction, exorbitant cost, and often questionable reliability meant that the European racing four-strokes of the 1990s were for the bulging of wallet and bold of spirit.

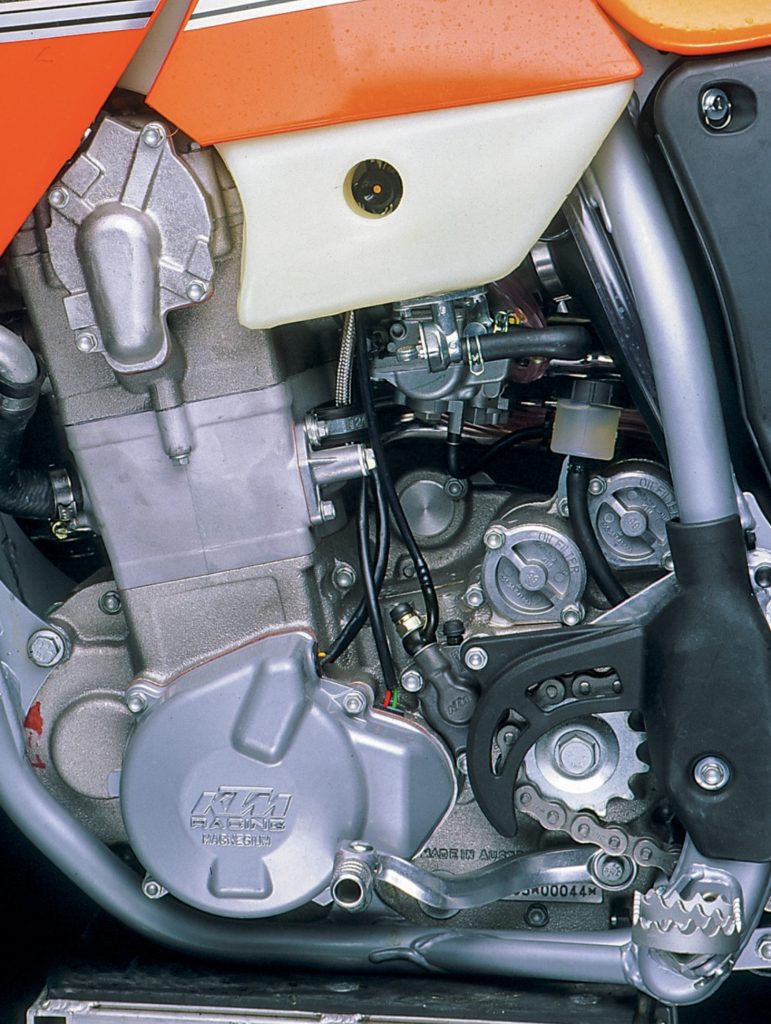

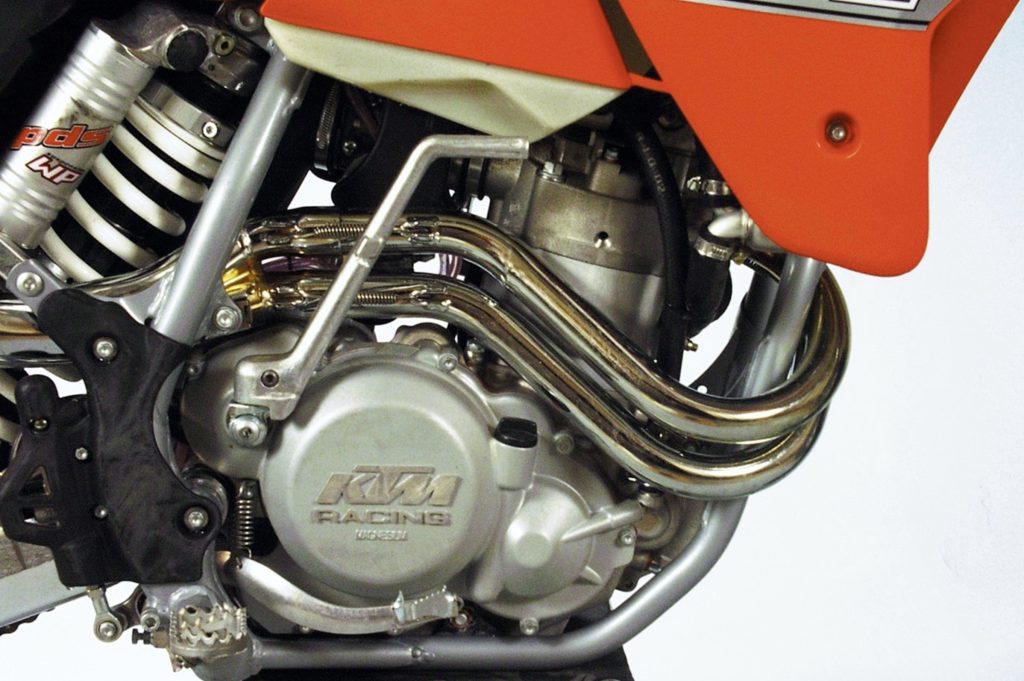

KTM’s new RFS mill shared more than a passing resemblance to a Husaberg design but there were several changes unique to KTM’s 510cc SOHC power plant. Photo Credit: KTM

KTM’s new RFS mill shared more than a passing resemblance to a Husaberg design but there were several changes unique to KTM’s 510cc SOHC power plant. Photo Credit: KTM

In 1995, KTM decided to get in on this four-stroke renaissance by purchasing Husaberg’s struggling motorcycle operations. This allowed the Austrians to widen their four-stroke portfolio and take advantage of Husaberg’s extensive engineering and racing experience. At the time, KTM’s four-strokes were large and extremely heavy machines with DNA that could be traced back to the LC-4s of the 1980s. They were great dual sports and decent Enduro machines, but not much of a motocrosser. With the acquisition of Husaberg, KTM bought themselves a jump start on developing the next generation of orange thumpers.

One of the major innovations that made the modern four-stroke renaissance possible was Keihin’s FCR carburetor. Like Yamaha’s YZ400/426F, KTM’s new 520 relied on the FCR to provide it with clean carburetion and excellent response. Photo Credit: KTM

One of the major innovations that made the modern four-stroke renaissance possible was Keihin’s FCR carburetor. Like Yamaha’s YZ400/426F, KTM’s new 520 relied on the FCR to provide it with clean carburetion and excellent response. Photo Credit: KTM

Despite the Husaberg acquisition, KTM appeared to be just as shocked by the success of the YZ400F as their rivals. The mainstream acceptance of the Yamaha four-stroke proved that if you sanded off the rough edges and dialed down the quirk, there was a huge market for a modern Open class four-stroke machine. With that in mind, the team in Mattighofen set about designing a machine that could go head-to-head with Yamaha’s revolutionary five-valve wonder.

The 520SX shared most of its bodywork with its 250 two-stroke stablemate but with its compact engine cases and unique fuel tank, the 520 offered the slimmest ergonomics in the KTM lineup. Photo Credit: KTM

The 520SX shared most of its bodywork with its 250 two-stroke stablemate but with its compact engine cases and unique fuel tank, the 520 offered the slimmest ergonomics in the KTM lineup. Photo Credit: KTM

The same year that Yamaha introduced the YZ400F, KTM also unveiled the biggest redesign of their motocross lineup in nearly a decade. The all-new deeper orange 1998 KTMs featured bold new styling, revamped motors, and a unique suspension package. Up front, the new machines relied on WP’s massive 50mm “Extreme” conventional forks. Out back, the new chassis kept the single shock but eliminated the rising rate “Pro-Lever” linkage that every full-size KTM had used since its introduction in 1982. By carefully placing the shock and employing a new WP Progressive Damping System (PDS) shock, KTM claimed they were able to enjoy the benefits of a linkage while bypassing the weight, complexity, and packaging compromises inherent to a traditional linkage rear suspension design.

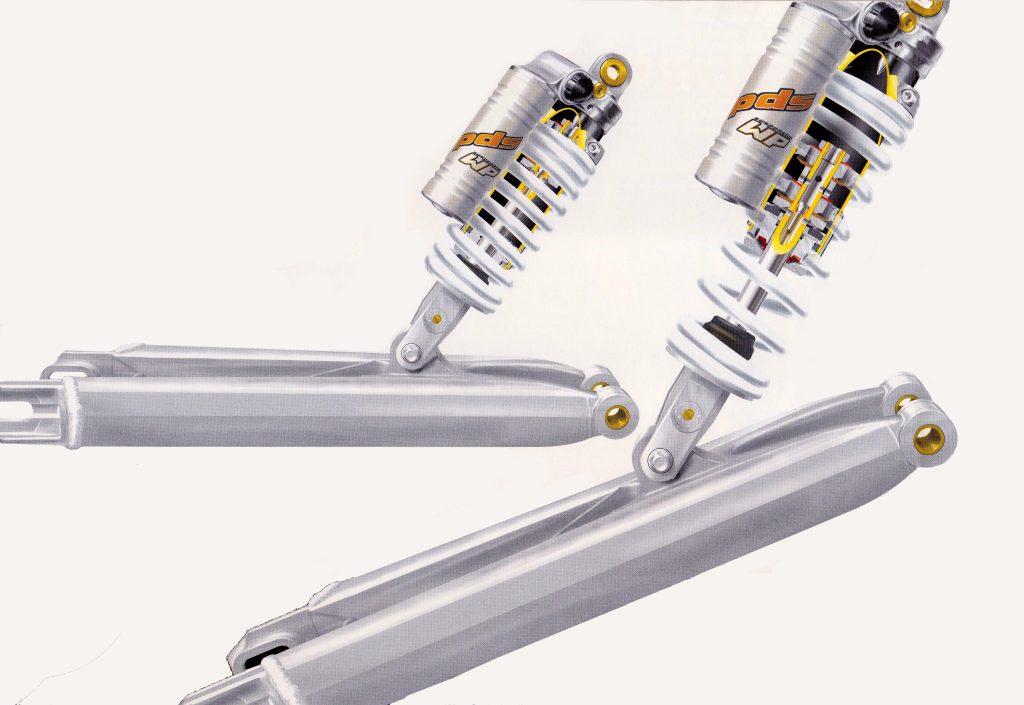

The main feature that set KTMs of the 2000s apart from their Japanese rivals was the Austrian’s reliance on WP’s “no-link” PDS rear suspension system. The advantages of the no-link were its reduced maintenance, lighter weight, and simplified packaging that allowed for superior airflow to the motor. Photo Credit: KTM

The main feature that set KTMs of the 2000s apart from their Japanese rivals was the Austrian’s reliance on WP’s “no-link” PDS rear suspension system. The advantages of the no-link were its reduced maintenance, lighter weight, and simplified packaging that allowed for superior airflow to the motor. Photo Credit: KTM

On the track, these new-generation KTMs went a long way toward winning over riders that had long ago written off the Austrian brand. The ergonomics were more in line with a traditional Japanese machine and the motors and suspension performed well enough to keep the orange machines on the radar of potential buyers. Not everyone loved the “no-link” rear suspension’s unique feel, but it performed excellently off-road and worked well enough in most conditions other than Supercross. Overall, the ‘98 KTMs proved that the Austrians were both willing to go their own way and more than capable of building machines that could run with the Japanese.

The 520SX’s stock four-speed transmission limited its appeal somewhat for riders looking for a “do-it-all” machine. Photo Credit: KTM

The 520SX’s stock four-speed transmission limited its appeal somewhat for riders looking for a “do-it-all” machine. Photo Credit: KTM

Over the next two years, Yamaha solidified its domination of the four-stroke arena with record sales and remarkable on-track success. In 1998, Doug Henry took his Yamaha YZ400F to the 250 National Motocross title, and in 1999, Italy’s Andrea Bartolini backed that up with Yamaha’s first victory in the 500 World Championships since Håkan Carlqvist in 1983. Open-class racing both in the US and abroad quickly became the domain of Yamaha’s incredible super thumper.

The new 520SX relied on a single overhead cam, four valves per cylinder, and rocker arms for its valvetrain. Photo Credit: KTM

The new 520SX relied on a single overhead cam, four valves per cylinder, and rocker arms for its valvetrain. Photo Credit: KTM

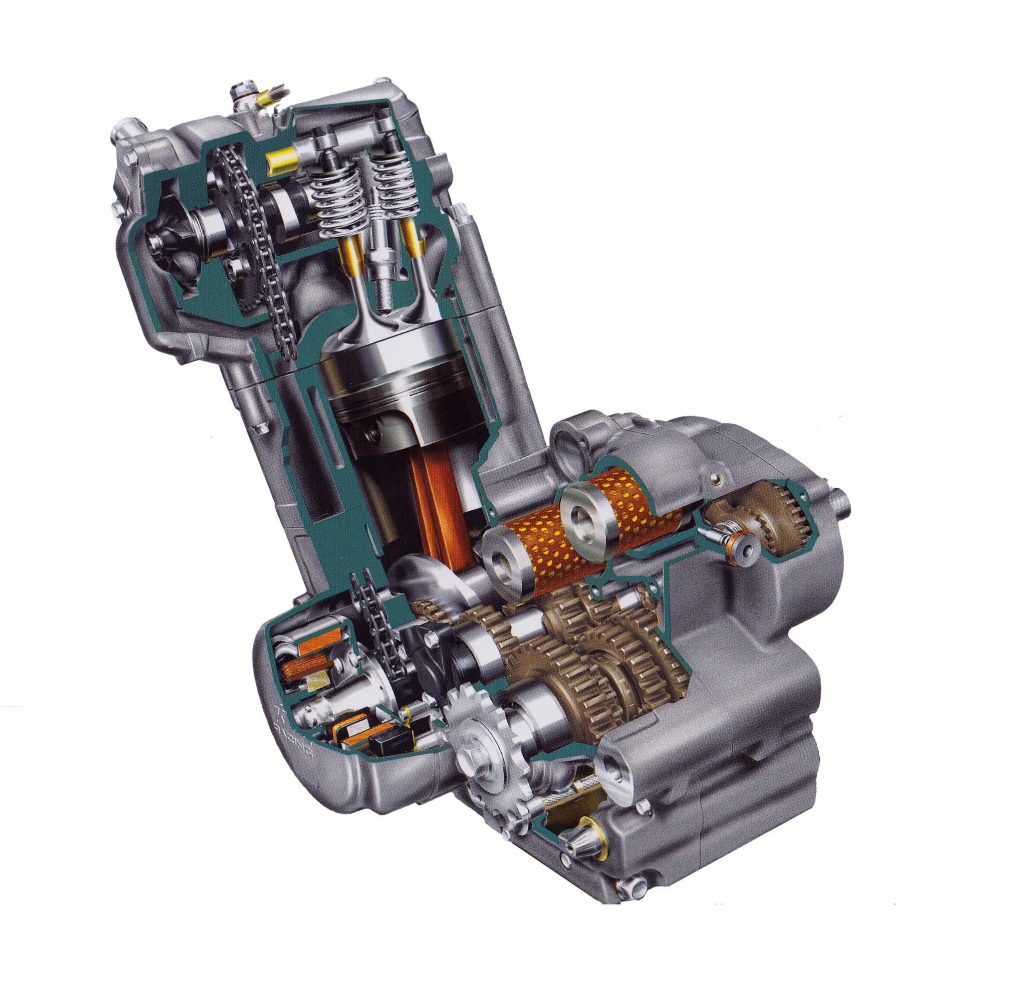

Finally, in 2000, KTM’s YZ400F fighter was ready to make its debut. Dubbed the 520SX, the all-new machine looked very much like a KTM 250SX with a Husaberg motor stuffed in its chassis. The top ends looked virtually identical and both machines shared features like a cam-driven water pump, single overhead cam, and four-valve layout. Even the clutch mechanisms were nearly identical between the Austrian and Swedish machines. With 510cc, the KTM offered a significant displacement advantage over the 426cc found in the revamped 2000 YZ426F. Both the YZ426F and 520SX employed the same 95mm bore, but the KTM featured a 12mm longer stroke than the Yamaha.

Over in Europe, Belgium’s Joël Smets took KTM’s all-new 520SX to his fourth 500 World Motocross title in 2000. Photo Credit: Mitch Friedman

Over in Europe, Belgium’s Joël Smets took KTM’s all-new 520SX to his fourth 500 World Motocross title in 2000. Photo Credit: Mitch Friedman

One of the major advantages the original YZ400F had enjoyed over its competitors was the superior carburetion of its Keihin FCR carburetor. This revolutionary mixer delivered previously unheard-of response and remarkably reliable performance. With the 520SX, KTM was not afraid to look to Japan for the best components, and choosing the FCR for carburetion duties was as easy as a no-brainer got in 2000. A Japanese Kokusan 4K3 ignition was installed and paired with a Throttle Position Sensor (TPS) to deliver the most precise combination of fuel and spark.

With four individual oil filters it was clear that KTM was serious about keeping the 520SX’s 1.2 quarts of oil free from debris. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With four individual oil filters it was clear that KTM was serious about keeping the 520SX’s 1.2 quarts of oil free from debris. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

One area where the Austrian and its Swedish inspiration parted ways was in the layout of the bottom end. Unlike the Husaberg, the new KTM featured a very Japanese-like left output shaft and right-side kicker. The new bottom end also featured two separate oil pumps and four filters (two paper and two filtration screens) to assure that the precious fluid remained clean and flowing properly. Unlike the YZF, which carried most of its oil in a tank housed in the frame, the new KTM kept its more modest 1.2 quarts inside the motor. This lowered weight but did afford less of a margin error if the oil was neglected. The new motor featured a counterbalancer to quell vibration that served double duty as a centrifuge to separate the oil from the air within the crankcase. The 520’s new transmission featured only four speeds, but the cases were designed to accept the off-road model’s six cogs if desired. Unlike the YZF, the all-new KTM featured a built-in decompression system and required no elaborate starting drill to get the big Katoom lit.

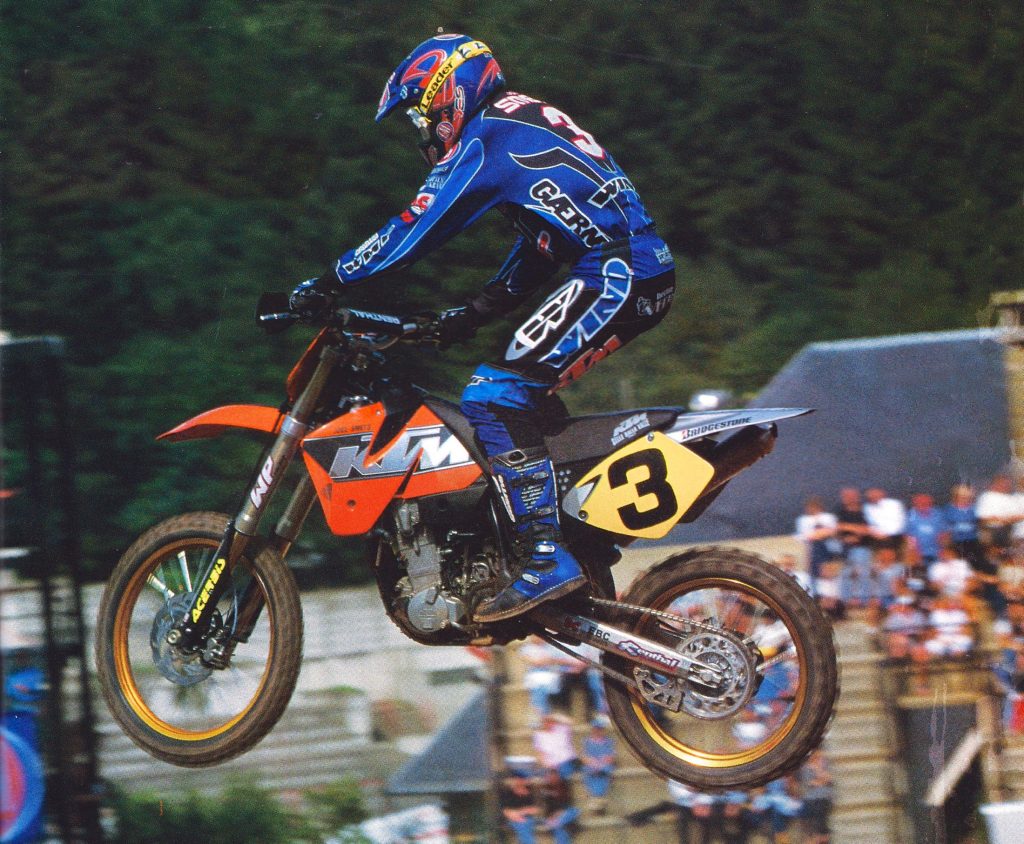

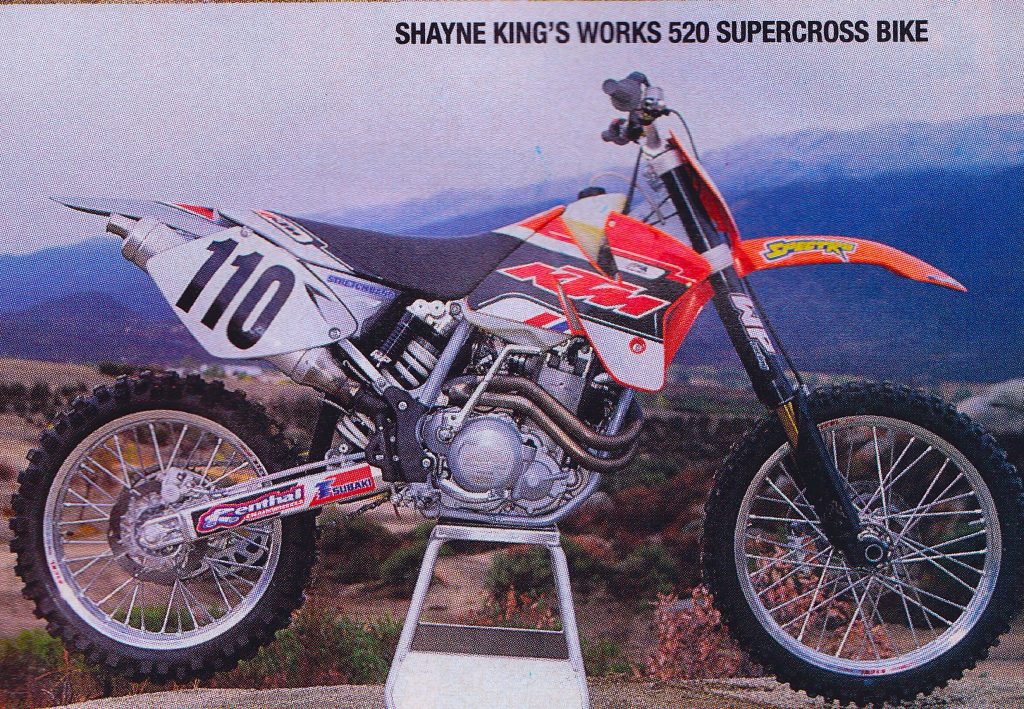

Back in America, New Zealand’s 1996 500 World Motocross champion Shayne King was tapped to race the new 520SX in Supercross and the AMA Nationals. Unfortunately, his season would turn out to be a massive disappointment with his best finish of the year being a 9th at High Point in May. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Back in America, New Zealand’s 1996 500 World Motocross champion Shayne King was tapped to race the new 520SX in Supercross and the AMA Nationals. Unfortunately, his season would turn out to be a massive disappointment with his best finish of the year being a 9th at High Point in May. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

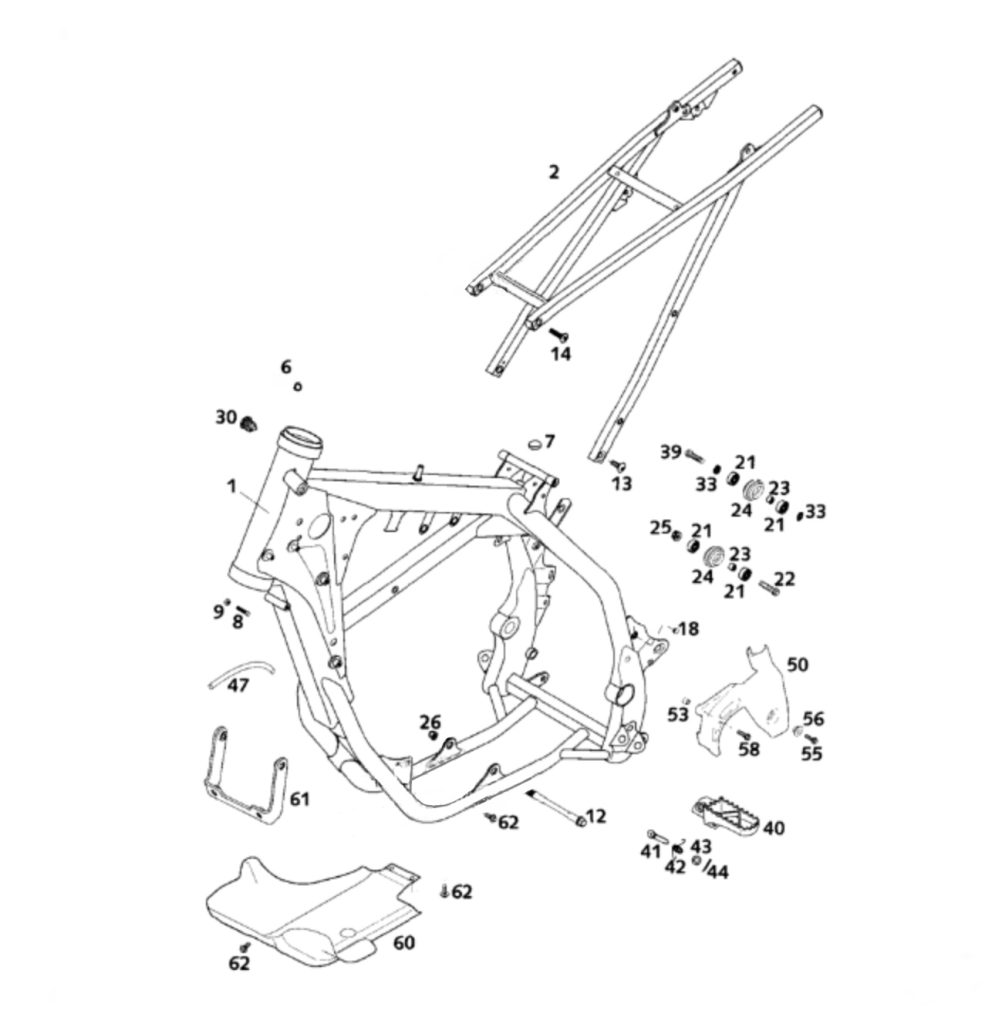

On the chassis front, the 520SX shared much of its DNA with its 250 two-stroke sibling. The 520SX’s new frame was crafted out of chromoly steel and featured geometry very similar to the 250SX. The engine cradle had to be enlarged to accommodate the big four-stroke engine but most of the frame was very similar between the two. Like the 250, the new 520 continued to use KTM’s unique no-link rear suspension paired with WP’s PDS rear damper. This design reduced weight, simplified maintenance, and allowed a streamlined airbox packaging that provided easy access and improved airflow. In use since 1998, KTM called the PDS the world’s first “intelligent” damper due to its ability to react to both speed and position input using two separate damping pistons. While KTM’s talking points proclaimed that the PDS would make linkages and suspension revalves obsolete, its performance on the track had proven less conclusive. For the new 520, KTM dialed up the third generation of their no-link shock dubbed PDS III. This new shock featured a progressive spring and revamped damping settings to accommodate the 520’s additional weight and power.

In 2000, KTM finally abandoned the conventional fork for good and mounted WP’s new 43mm inverted fork on the 520SX. While most testers felt it was not superior to the conventional design it replaced it did a decent job of providing on track comfort and control. Photo Credit: KTM

In 2000, KTM finally abandoned the conventional fork for good and mounted WP’s new 43mm inverted fork on the 520SX. While most testers felt it was not superior to the conventional design it replaced it did a decent job of providing on track comfort and control. Photo Credit: KTM

Up front, KTM joined Suzuki by finally abandoning the conventional fork experiment and switching back to an inverted fork design for 2000. Despite the affection of riders who loved the compliance of the new-generation conventional forks from Showa, Marzocchi, and WP, the race teams never warmed to their flexier feel. For 2000, KTM moved away from the conventional 50mm WP Magnum fork and replaced it with an all-new 43mm inverted WP design. The new fork delivered 11.6 inches of travel and offered external adjustments for compression and rebound control. Paired with the new forks was a redesigned clamp that offered four adjustable positions for the new oversized Magura aluminum handlebar. As with previous KTMs, the new 520SX featured a hydraulic clutch for precise and consistent clutch control and premium quality Brembo components for the dual hydraulic disc brakes. Perhaps most impressive was the KTM’s weight, which clocked in at 12 pounds lighter than the stock YZ426F.

Open class power in a smooth and controllable package was the calling card of KTM’s new 520SX. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

Open class power in a smooth and controllable package was the calling card of KTM’s new 520SX. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

On the track, the all-new 520SX proved to be every bit of the YZF competitor everyone had been hoping to see. The longer-stroke motor and heavier flywheel of the Austrian provided a more “traditional” four-stroke feel that was somewhere between the bark of the YZ426F and the chug of a big Rotax single. Down low, there was a ton of smooth torque, but less instant snap than the Yamaha. This made it super easy to get the Austrian hooked up and put every one of its 50+ horsepower to the ground. The midrange power was smooth and broad, and the orange machine just kept on pulling and pulling until the fun was cut off around 10,000 RPM. Unlike the YZF, which hit hard, revved fast and demanded respect, the big KTM doled out its power in a slower building crescendo of torque that was powerful but unintimidating. Twist the throttle a bit, and the 520SX hooked up and rushed forward. Twist the throttle a lot and the KTM hooked up and really rushed forward. At no point did the Katoom hiccup, lurch, snap, or snarl. It started easily, ran flawlessly, and shifted smoothly. Its four-speed transmission was a handicap off-road, but its mountainous torque curve meant it was no issue for motocross. Smooth, flexible, and incredibly fast, the KTM’s RFS mill was as pleasant as any Open class racer could be expected to be. There was more compression braking than on the Yamaha and some two-stroke converts preferred the quicker revving and harder-hitting YZF’s powerband to the more metered delivery of the 520. Both bikes were ridiculously fast with most comparisons of power coming down to personal preference. For true throttle jockeys, the Yamaha was racier, but in the opinion of many riders, the new KTM delivered the ultimate combination of Open class power and control.

With four selectable bar positions the 520SX offered a great deal of rider customization. Photo Credit: KTM

With four selectable bar positions the 520SX offered a great deal of rider customization. Photo Credit: KTM

On the chassis front, the new KTM was excellent in most respects. The rider compartment was incredibly narrow, and the bike felt even skinnier than its two-stroke cousin. Both the KTM and Yamaha were big bikes, but the 520 was significantly lighter and you could feel that on the track. Neither machine was going to be confused for an RM125, but the KTM did a better job of hiding its Open class waistline than the Yamaha. The KTM’s strong compression braking did a great job of loading the front tire in turns and the 520 was easily the most adept turner in the KTM lineup. High-speed stability was good, but the bike was not as unflappable at speed as the YZ426F. With the gyroscopic action of its 510cc motor and big-bore size, it was not easy to knock the KTM off its intended path, but there was the occasional bit of headshake to remind you to pay attention. Overall, most riders felt the Yamaha’s handling, ergonomics, and feel were slightly more refined, but the 520SX was a great handler and easily the most well-rounded chassis package ever offered by the Austrians.

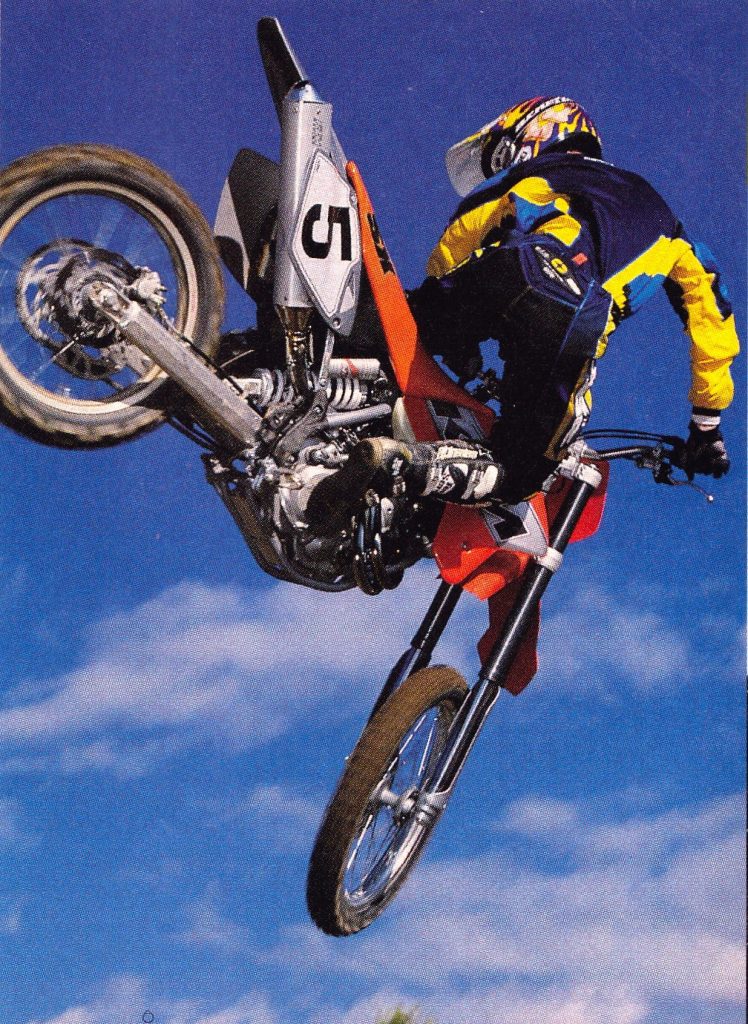

At 235 pounds the 520SX was only a few pounds heavier than Suzuki’s RM250 and significantly less than Yamaha’s hefty YZ426F. While still less flickable than a 250 smoker, the 520’s lighter weight was apparent on the track and in the air. Photo Credit: Garth Milan

At 235 pounds the 520SX was only a few pounds heavier than Suzuki’s RM250 and significantly less than Yamaha’s hefty YZ426F. While still less flickable than a 250 smoker, the 520’s lighter weight was apparent on the track and in the air. Photo Credit: Garth Milan

Pros and Supercross specialists had more of an issue with KTM’s PDS rear suspension than most mere mortals did. For outdoor motocross, the PDS worked well and offered performance comparable to its linkage-equipped rivals. Most riders still felt the YZ426F’s shock was superior but it was far from the serious handicap many pundits today would have you believe. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Pros and Supercross specialists had more of an issue with KTM’s PDS rear suspension than most mere mortals did. For outdoor motocross, the PDS worked well and offered performance comparable to its linkage-equipped rivals. Most riders still felt the YZ426F’s shock was superior but it was far from the serious handicap many pundits today would have you believe. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the suspension front, the new KTM was once again the most well-rounded machine in the KTM lineup. The new 43mm inverted WP units were not as smooth as the Kayaba forks used on the YZF, but they did a good job of handling the track. The initial travel was a bit stiff, but the 520’s weight and power delivery did a better job of getting them to work than on the KTM two-strokes. If pushed, they tended to blow through the travel faster than most riders liked but the forks were certainly raceable in stock condition. Neither fork was perfect, but most riders rated the Yamaha as having the superior silverware in 2000.

The KTM’s new 510cc SOHC motor offered a very different riding experience from Yamaha’s 426cc short-stroke DOHC Genesis mill. Where the Yamaha hit hard and revved fast, the KTM thundered and chugged with a smooth crescendo of torque that clawed at the ground and launched the orange machine forward at quasar speed. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The KTM’s new 510cc SOHC motor offered a very different riding experience from Yamaha’s 426cc short-stroke DOHC Genesis mill. Where the Yamaha hit hard and revved fast, the KTM thundered and chugged with a smooth crescendo of torque that clawed at the ground and launched the orange machine forward at quasar speed. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Out back, the KTM’s PDS shock once again proved somewhat polarizing. The “Smart Shock” tracked well in the rough and did a great job of putting the KTM’s power to the ground. On a choppy and blown-out motocross track the big Katoom stuck like glue and clawed for every ounce of available traction. Once again, the 520’s smooth power and increased weight paid major dividends here with the four-stroke’s shock offering superior action to that of KTM’s two-stroke machines. While the shock tracked well, it offered a different feel that not everyone was comfortable with. The lack of a linkage seemed to lessen the “pop” riders got when preloading to clear certain obstacles and the bike felt slightly loose and underdamped on big hits. It never did anything weird and reacted well when bottomed but most riders still preferred the more familiar feel of the Yamaha’s traditional shock and linkage.

Premium-quality components like the Brembo brakes, Magura oversized alloy bars, and a hydraulic clutch set the KTM apart from its Japanese competitors. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Premium-quality components like the Brembo brakes, Magura oversized alloy bars, and a hydraulic clutch set the KTM apart from its Japanese competitors. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the detailing front, the KTM was excellent in keeping with its premium price tag. At $6548 it was $650 more expensive than the Yamaha but still a good bit less expensive than the Husaberg, VOR, and soon-to-be-released Cannondale. The hydraulic clutch, oversized Magura aluminum handlebar, durable graphics, kick-and-go starting, and powerful Brembo brakes all spoke to the KTM’s status as a premium product. While finding someone to dial in the WP fork and shock was somewhat difficult at times, the lack of a linkage was welcome to anyone who had dealt with servicing these grease-hungry components. The side access airbox also made cleaning the filter a much less arduous task. The KTM’s slim ergonomics and comfortable layout were liked by most but the hard seat foam KTM continued to use was less appreciated. Many also commented that a bike with this much power could have benefited from a less slippery seat cover. The translucent gas tank gave the bike a bit of an “off-road” look that not everyone enjoyed but it did make it much easier to see the gas level of the big Katoom. This proved to be helpful as the 520 seemed to suck down fuel at a much greater rate than the more miserly Yamaha. While the automatic decompression system was a godsend, the lack of a “hot-start” circuit seemed like a glaring oversight on a type of machine notorious for its often stubborn starting. That said, the KTM proved to be a very reliable starter and much less finicky than the YZF.

While the new 520SX offered a ton of performance its limited production numbers and KTM’s smaller dealer network meant it was not a real threat to Yamaha’s dominance in the marketplace. In the end, it would take Honda and the introduction of their CRF450R in 2002 to challenge the blue machine for sales supremacy. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

While the new 520SX offered a ton of performance its limited production numbers and KTM’s smaller dealer network meant it was not a real threat to Yamaha’s dominance in the marketplace. In the end, it would take Honda and the introduction of their CRF450R in 2002 to challenge the blue machine for sales supremacy. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

While the RFS motor proved to be largely bulletproof overall, its relatively small oil capacity necessitated that owners keep a close eye on the oil level and service its myriad of filters regularly. This was one area where Yamaha and its external oil tank and larger oil capacity had a significant advantage. If you kept on top of the oil and maintenance, however, the 520SX was extremely reliable and capable of going over 100 hours before needing a major servicing. Like the Yamaha, this went a long way toward allaying riders’ fears about the expense of owning and racing a four-stroke.

Big, powerful, and beautifully built, KTM’s 520SX offered riders willing to eschew the status quo a legitimate racing alternative to the ubiquitous YZ400/426F. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Big, powerful, and beautifully built, KTM’s 520SX offered riders willing to eschew the status quo a legitimate racing alternative to the ubiquitous YZ400/426F. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the end, the 2000 KTM 520SX proved to be just the legitimate competitor to the YZ426F many had been hoping for. Unlike the cobby exotics and vaporware Cannondale, the KTM was a well-sorted, reliable, and extremely capable Open class four-stroke with all the performance and very few of the drawbacks of a traditional four-stroke. It was light, wicked fast, easy to ride, easy to start, and comfortable. KTM’s engineers used a decade of Husaberg’s racing experience to produce the most competitive KTM ever. Many riders still preferred the racier and more familiar Yamaha, but if you took the road less traveled and bought the KTM, you were not likely to regret that decision.

For your daily dose of classic moto goodness make sure to follow me @tonyblazier on Instagram and Twitter