For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s all-new 2000 XR650R.

Honda’s all-new XR650R was not the WR426F competitor some had hoped for, but for XR enthusiasts it offered the reliability, quality, comfort, and performance the big red thumpers had become legendary for. Photo Credit: Honda

Honda’s all-new XR650R was not the WR426F competitor some had hoped for, but for XR enthusiasts it offered the reliability, quality, comfort, and performance the big red thumpers had become legendary for. Photo Credit: Honda

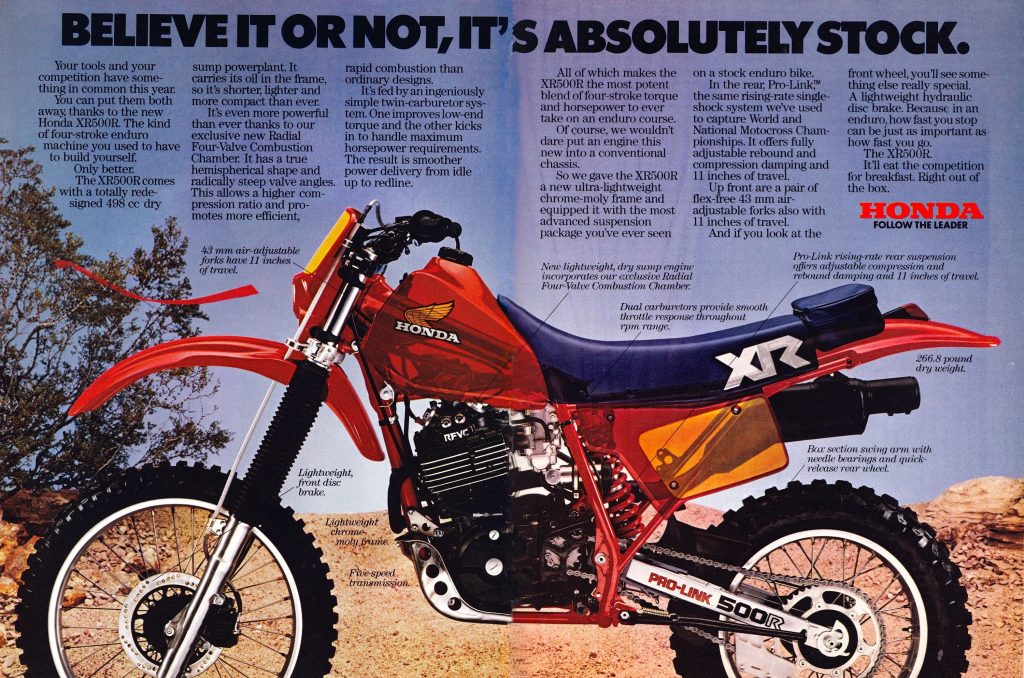

In 2000, Honda set about replacing one of the most successful and iconic off-road machines of all time. Originally introduced in 1979 as the XR500, Honda’s big-bore four-stroke quickly became the preferred machine of desert rats and off-road four-stroke enthusiasts. The big XRs were heavy and often undersuspended, but their endless mountains of torque and rugged simplicity proved to be the perfect basis for turning a big bore plaything into a lethally effective racer. Modified XRs could be found snaking through the woods, bombing across the desert, and even roosting around the occasional motocross track

Honda’s big-bore XRs started their run in 1979 with the introduction of the first XR500.

Honda’s big-bore XRs started their run in 1979 with the introduction of the first XR500.

Upgraded to 591cc in 1985, the newly christened XR600R became the Japanese four-stroke to beat in the mid-eighties. By 1988, Yamaha had retired their TT600 and Suzuki’s DR500 was a distant memory. Big four-strokes from KTM and Husqvarna persisted, but their liquid cooling, more sophisticated suspension, and higher price points seemed aimed at a different clientele than the do-it-all XR. Despite its relative lack of sophistication, however, the air-cooled XR proved to be an incredibly capable racer. During its 21-year run, the XR500/XR600R captured nine Baja 1000 titles, five Grand National Cross Country championships, four Hair Scrambles titles, and even the occasional World Four-Stoke Motocross title with riders like Ron Lechien and Johnny O’Mara at the controls. Big, burly, and bulletproof, the XR600R was the ultimate every-man racer of the 1980s and 1990s.

In 1983, Honda revamped their XR500R with an all-new chassis and updated motor featuring the Radial Four Valve Combustion (RFVC) design that would become a staple of the XR line for the next 21 years. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1983, Honda revamped their XR500R with an all-new chassis and updated motor featuring the Radial Four Valve Combustion (RFVC) design that would become a staple of the XR line for the next 21 years. Photo Credit: Honda

With this illustrious resume as a backdrop, Honda set about replacing its iconic thumper with an all-new machine in 2000. Two years prior, Yamaha had reignited four-stroke enthusiasm with the introduction of the amazing YZ400F motocrosser and off-road-focused WR400F. The YZ and WR were unlike any previous Japanese four strokes with high-tech short-stoke motors, dual overhead cams, and road-race-inspired five-valve Genesis heads. Their quick-revving short-stroke architecture gave them power characteristics that were the polar opposite of the torquey and slow-revving XRs. The Yamahas spooled up quickly and revved to the moon with seamless power delivery and utter lack of XR “chug”.

In 1988, Honda introduced the last major update of the XR600R with a new more powerful motor, updated suspension, and revamped bodywork. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

In 1988, Honda introduced the last major update of the XR600R with a new more powerful motor, updated suspension, and revamped bodywork. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

With the tremendous successes of the new Yamaha four-strokes, some people hoped that the all-new XR would be Honda’s answer to the WR400F, but Honda’s engineers had a different mission in mind; the XR was developed purely as a replacement for the more than decade-old XR600R. This meant a focus on durability and comfort over outright power and performance. While the new XR would surely do battle with the WR400F in some arenas, its much larger displacement and more traditional motor design meant the two were aimed at very different consumers.

During the 1990s Scott Summers and the Honda XR600R became one of the most successful combinations in off-road racing. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

During the 1990s Scott Summers and the Honda XR600R became one of the most successful combinations in off-road racing. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The all-new XR650R featured a unique alloy frame that built off of the experience Honda gained with their first-generation aluminum CRs. Photo Credit: Honda

The all-new XR650R featured a unique alloy frame that built off of the experience Honda gained with their first-generation aluminum CRs. Photo Credit: Honda

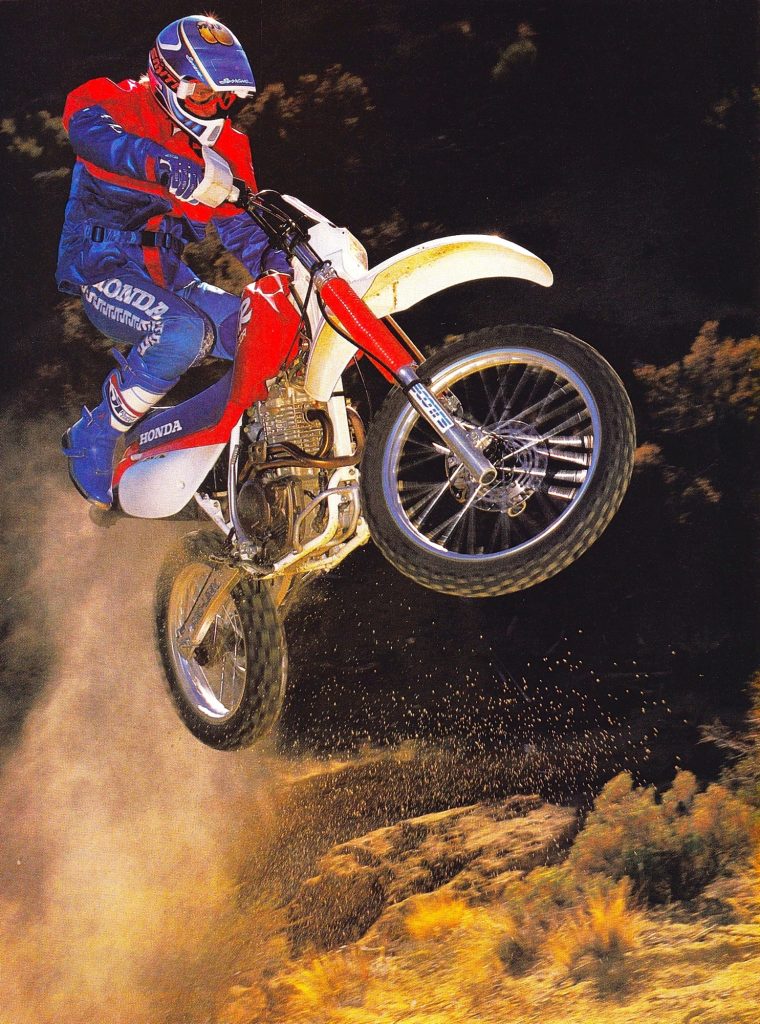

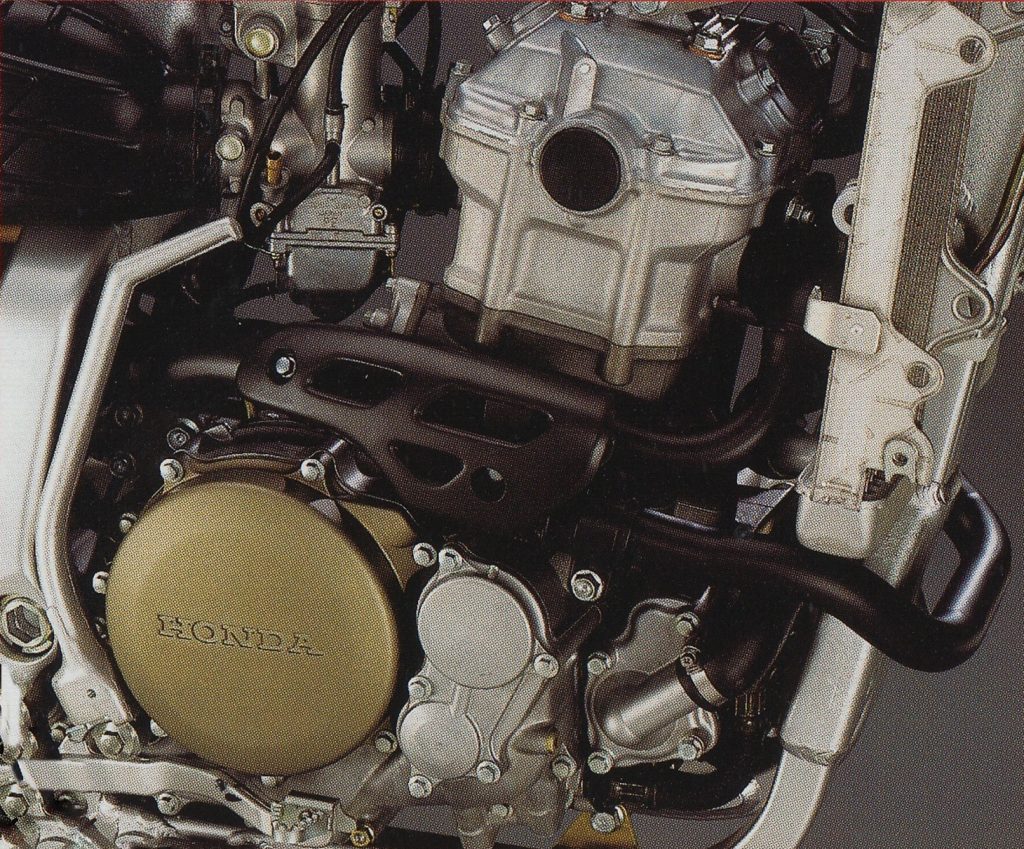

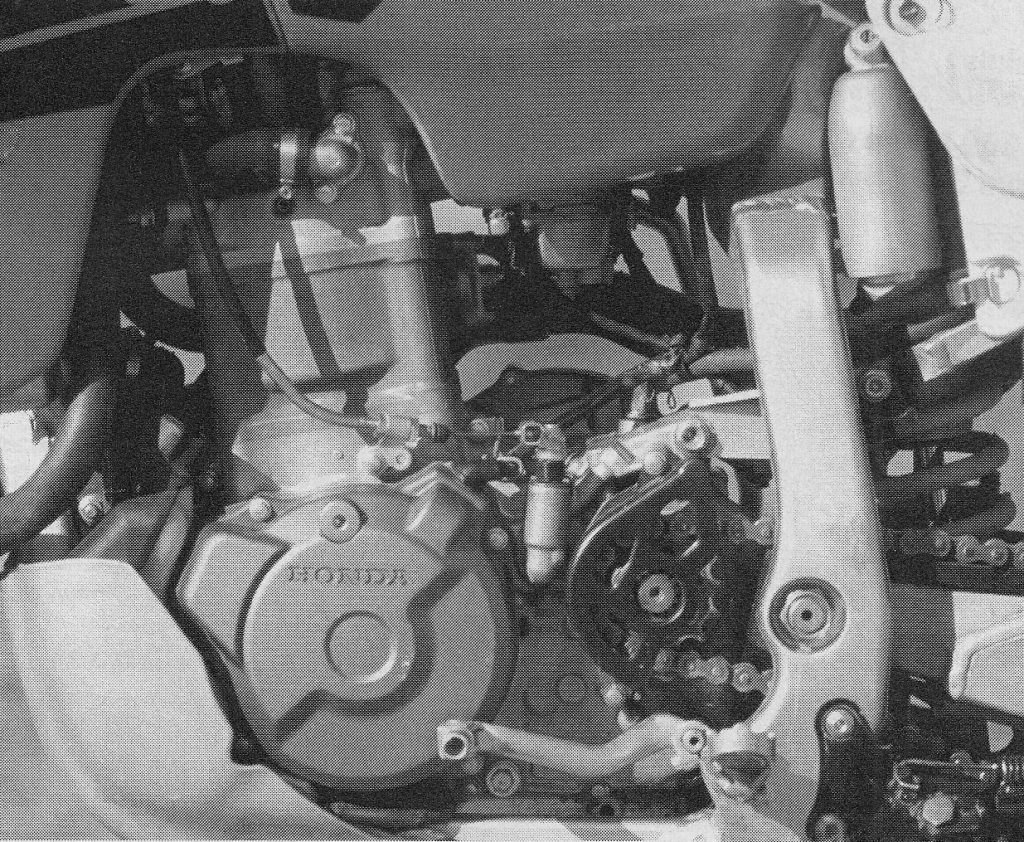

With the motor design for the all-new “Super XR,” Honda’s engineers took a far more conservative approach than Yamaha had with the YZ/WR. The new motor’s 100mm x 82.6mm bore and stroke were very similar to the outgoing XR600R’s dimensions. Both motors relied on a four-valve head, but the new design finally retired the Radial Four Valve Combustion (RFVC) configuration in use on the XRs since 1983. Honda had long felt that the reliability of air-cooling outweighed the performance gains of liquid-cooling for their XRs, but the new 650 finally broke that tradition by offering dual radiators to keep the big single’s temps under control. Large 37mm intake valves and 32mm exhaust valves helped the big 649cc mill inhale and exhale effectively. The new top end featured Nikasil coating on the cylinder for optimum cooling and durability and retained the dry-sump design of the previous generation. A counterbalancer was added to quell vibration from the big single and a new Husaberg-style reed valve was added to the crankcase to help circulate engine oil through the gearbox. The new motor separated the engine oil from the ignition rotor to provide reduced drag and added an automatic cam-chain tensioner to simplify maintenance.

Large dual radiators brought liquid cooling to the XR line for the first time. Photo Credit: Honda

Large dual radiators brought liquid cooling to the XR line for the first time. Photo Credit: Honda

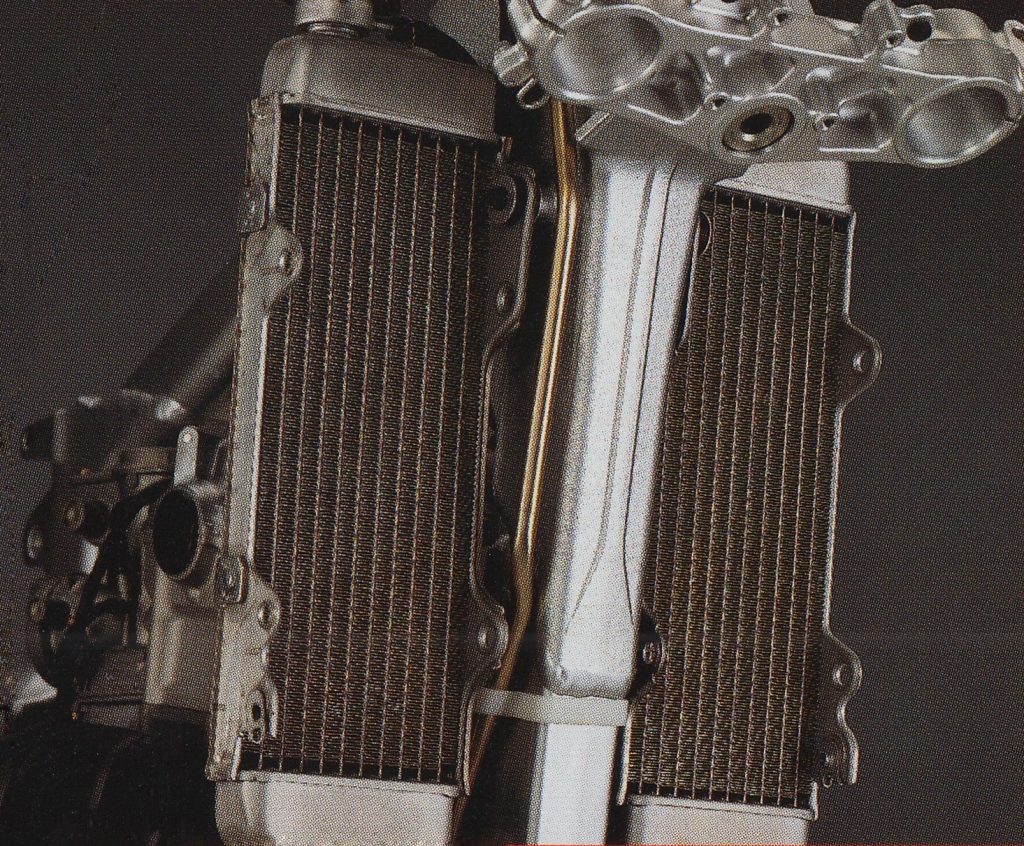

The XR650R’s new alloy frame featured an internal oil tank to increase oil capacity and aid engine cooling. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The XR650R’s new alloy frame featured an internal oil tank to increase oil capacity and aid engine cooling. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The redesigned motor dropped 10 pounds from the old, air-cooled mill but still clocked in at a hefty 88 pounds dry. Today, electric starting would be expected, but in 2000 kicking was still the status quo so the new XR made do without the push-button start found on the XL650L dual sport. The big 650 required a hefty kick to spin its coffee can-sized piston, but it did feature primary kickstarting to allow starting in any gear and an automatic compression release for convenience. A large 40mm piston-valve carburetor fed fuel to the beast and featured a special low-friction coating that Honda claimed reduced throttle effort by 22 percent. As before, a wide-ratio five-speed gearbox and manual clutch put the XR’s prodigious torque to the ground. A new removable clutch cover was crafted out of magnesium to save weight and offered easy access to the clutch for the first time. A large set of stainless-steel headers funneled exhaust to a massive single steel muffler which was equipped with a US Forestry-approved spark arrestor to keep sound down and appease Uncle Sam.

The XR’s all-new liquid-cooled 649cc mill featured a single overhead cam, a Nikasil cylinder liner, four valves, and a mild state of tune. In stock condition, the XR was a big pussycat, but there was serious power lurking inside its alloy castings just waiting to be released. Photo Credit: Honda

The XR’s all-new liquid-cooled 649cc mill featured a single overhead cam, a Nikasil cylinder liner, four valves, and a mild state of tune. In stock condition, the XR was a big pussycat, but there was serious power lurking inside its alloy castings just waiting to be released. Photo Credit: Honda

While the XR’s new motor was far from groundbreaking, its redesigned chassis was state-of-the-art. In 1997, Honda introduced the industry’s first production alloy motocross chassis on their all-new CR250R. The twin-spar aluminum frame was super trick but also super stiff, and many felt the old steel frame was a better performer. With the XR650R, Honda took a very different approach to its frame design. With its hefty 287-pound weight and big power, Honda still felt aluminum was the right choice for the frame, but the new chassis was designed to be more compliant than the ultra-rigid first-generation CR chassis. Honda knew that the new frame would need to be stout to combat flex, but comfort was key to a machine designed to be ridden a thousand miles across the Baja peninsula.

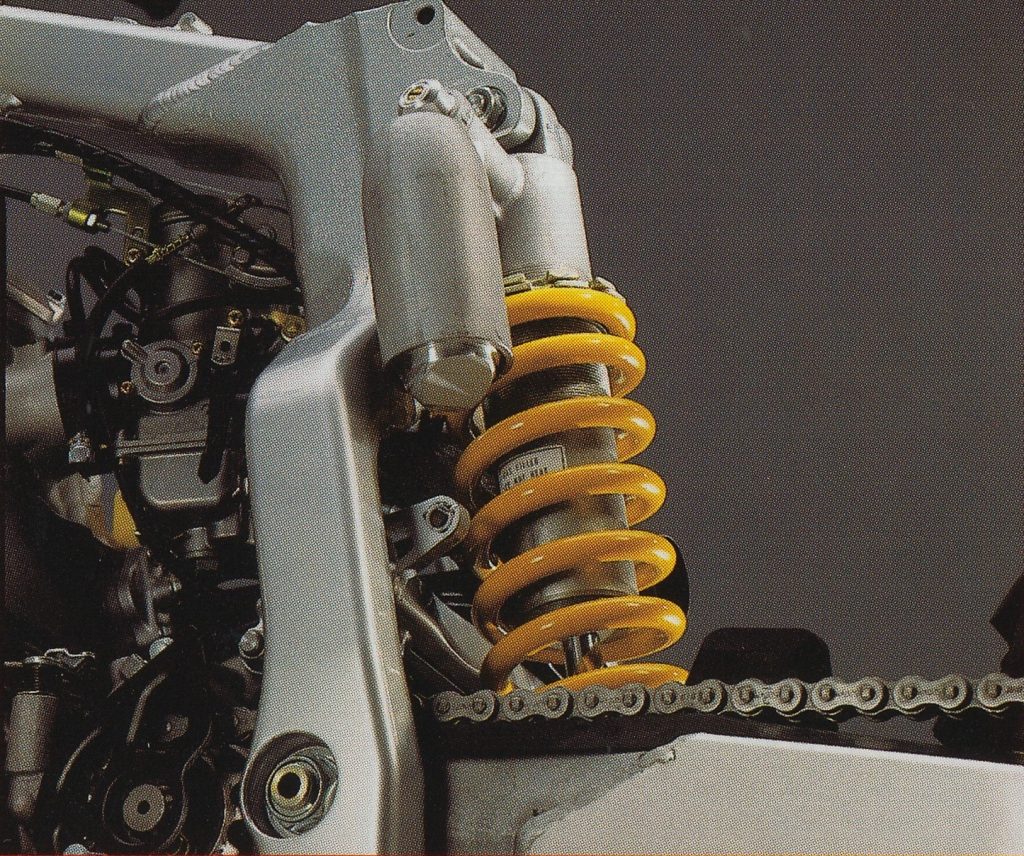

The XR’s all-new Kayaba shock featured a larger shaft, increased oil capacity, and greater travel than the Showa unit found on the XR600R. Photo Credit: Honda

The XR’s all-new Kayaba shock featured a larger shaft, increased oil capacity, and greater travel than the Showa unit found on the XR600R. Photo Credit: Honda

Unlike the CR’s twin-spar frame, the new XR maintained a more traditional single backbone construction. This was done to dial in the best balance of strength and comfort, reduce chassis width, and allow for the most available fuel capacity. Like the previous XR600R and Yamaha’s WR400F, the new frame featured an internal oil tank to increase oil capacity and keep the temps down. The main frame backbone was built in a convex shape to increase strength while the swingarm pivot was built around pressure-formed alloy plates that employed the engine cases for additional support. The swingarm, Pro-Link linkage, and detachable subframe were all crafted out of aluminum with the top shock mount being integral to the frame’s design. The new frame offered slightly more rake and trail than the old XR chassis and featured a one-inch increase in wheelbase. Interestingly, Honda also decided to clearcoat the frame despite its aluminum construction.

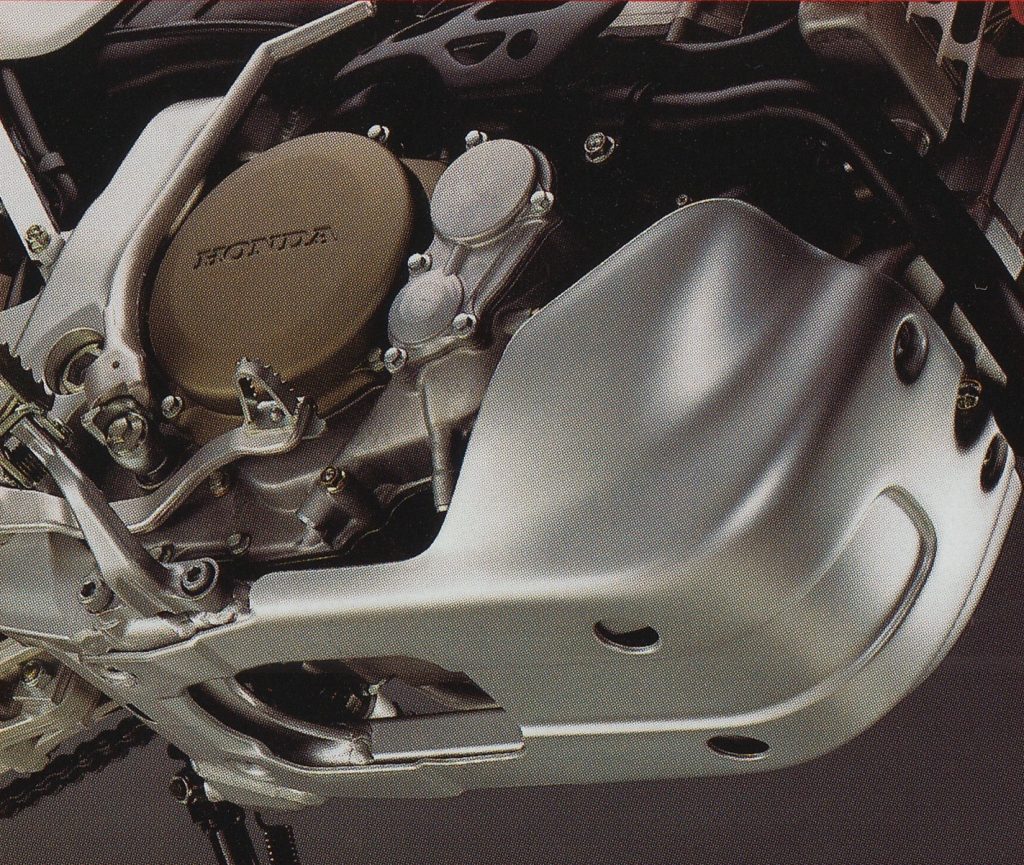

A large plastic skid plate protected the underside of the motor and the standard coolant catch tank. Photo Credit: Honda

A large plastic skid plate protected the underside of the motor and the standard coolant catch tank. Photo Credit: Honda

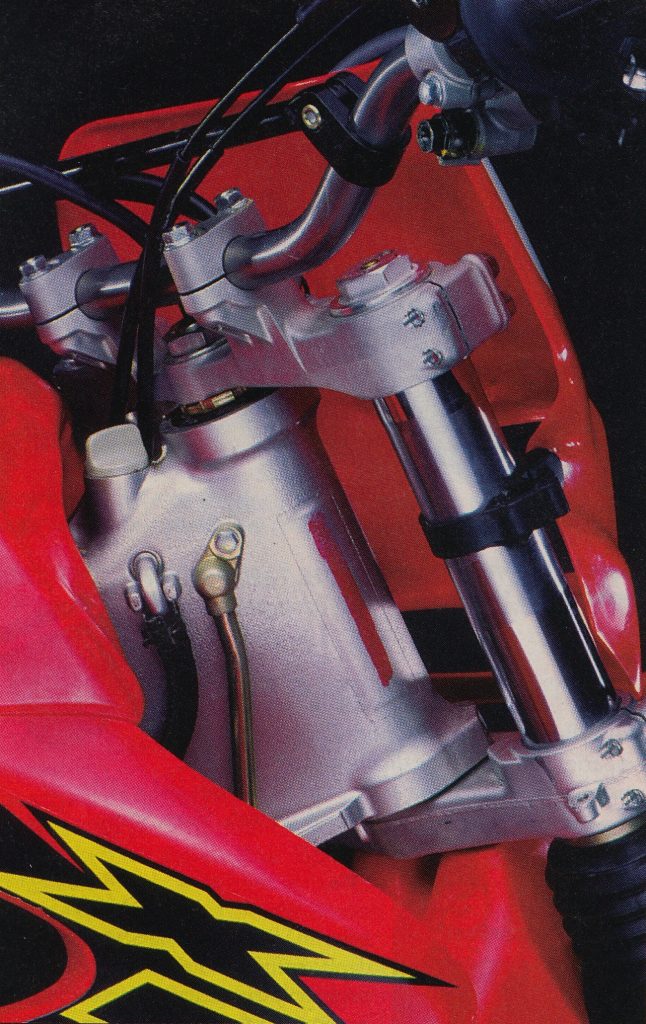

On the suspension front, the XR once again showed its bias toward comfort over control. Unlike the WR400F, which featured the very latest in motocross-spec suspension, the XR650R chose to rely on older and more off-road-focused technology. Up front, the new XR featured a 46mm conventional cartridge fork that was very similar to the one that graced Kawasaki’s KX line a decade before. The new fork was 3mm larger in diameter than the outgoing design and featured 41mm less underhang below the front axle. The fork’s internal cartridge was 5mm larger in capacity and offered greater adjustability by adding rebound to the previous design’s adjustable compression settings. While larger in diameter, the new fork did offer 0.4 inches less travel than the older Showa design.

In a nod to comfort over control, Honda chose to stick with conventional forks for the all-new XR650R. The 46mm Kayaba cartridge units were internally similar to the forks found on Kawasaki’s 1989 KX line but advances in design offered less underhang below the axle to prevent the XR from catching in deep ruts and rocks. Photo Credit: Honda

In a nod to comfort over control, Honda chose to stick with conventional forks for the all-new XR650R. The 46mm Kayaba cartridge units were internally similar to the forks found on Kawasaki’s 1989 KX line but advances in design offered less underhang below the axle to prevent the XR from catching in deep ruts and rocks. Photo Credit: Honda

In the rear, the XR featured an all-new Kayaba piggyback shock with a 2mm larger shock shaft and 27mm more shaft travel. When paired with the all-new Pro-Link linkage this translated to 12.1 inches of rear wheel travel. This was a 1.1-inch increase over the previous design. As before, the rear damper offered external adjustments for spring preload, compression, and rebound damping.

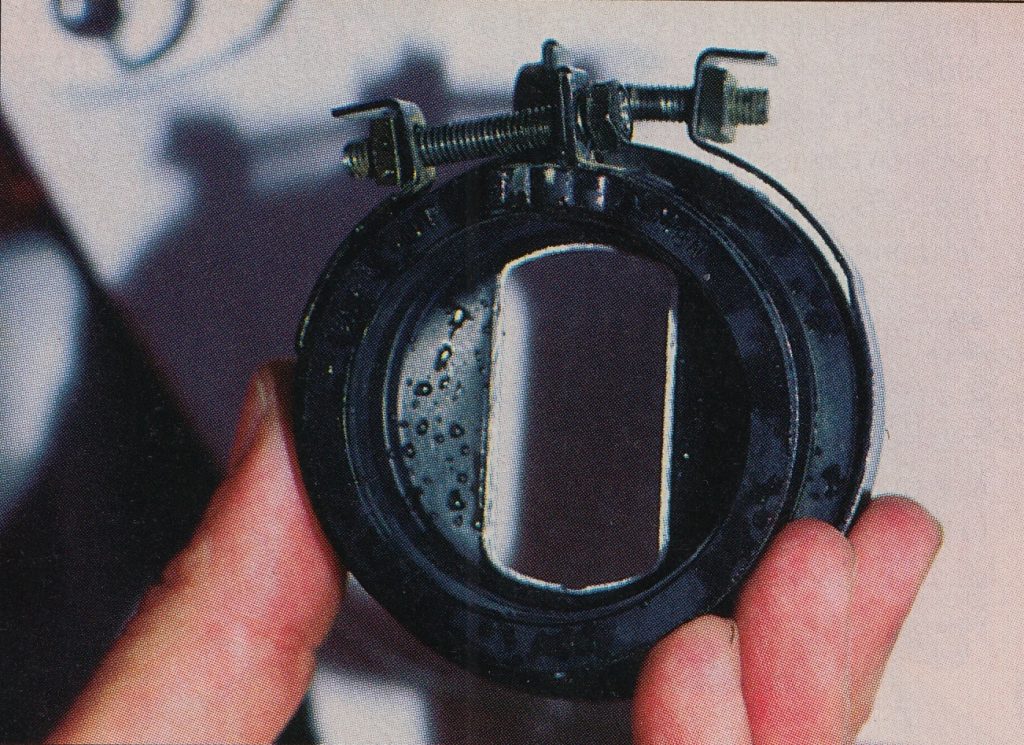

A restrictor built into the stock intake choked the air inlet down to half its full size. Honda’s optional “Power Up” kit removed that restriction and doubled the core size of the muffler to allow the 650 to inhale and exhale to its full potential. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

A restrictor built into the stock intake choked the air inlet down to half its full size. Honda’s optional “Power Up” kit removed that restriction and doubled the core size of the muffler to allow the 650 to inhale and exhale to its full potential. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

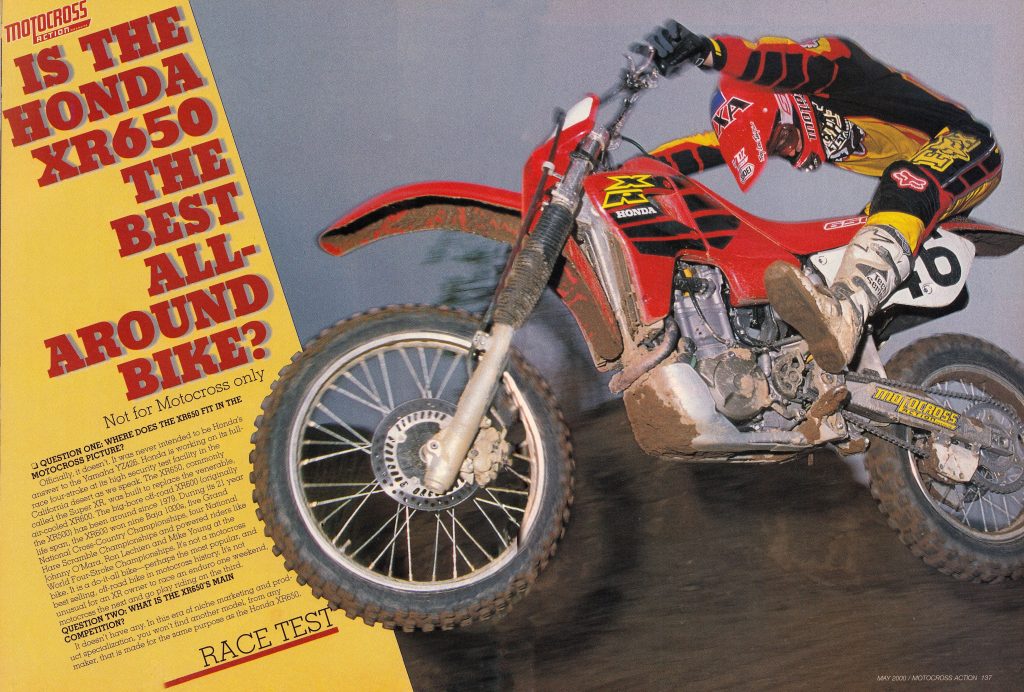

While the XR650R was developed strictly as an off-roader, that did not prevent some riders from taking the big thumper to the occasional motocross course. When Motocross Action tested the all-new XR in 2000, they came away impressed with just how great of an all-around machine the big 650 was. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the XR650R was developed strictly as an off-roader, that did not prevent some riders from taking the big thumper to the occasional motocross course. When Motocross Action tested the all-new XR in 2000, they came away impressed with just how great of an all-around machine the big 650 was. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

All-new bodywork graced the XR650R with a redesigned pilot’s compartment and updated styling. While the new machine looked quite large, the updated ergonomics were significantly slimmer than the old XR600R. The large seat was considerably more comfortable than the thin motocross-style perch found on the WR400F, and the tank featured the same 2.6 gallons of fuel capacity as the old XR with a noticeably thinner feel. Large side plates made it easy to affix numbers and a slick easy access airbox featured a trick flat air filter that was designed to allow for spares to be easily carried in a fanny pack. Lights were standard front and rear with the XR ignition allowing for more powerful light setups if needed. New 240mm discs were added front and rear (20mm larger than the old rotor in the rear) with the front featuring a CR250R master cylinder to assure maximum power and excellent feel. A standard O-Ring chain, quality components, and a six-month warranty filled out the XR’s impressive list of features for 2000.

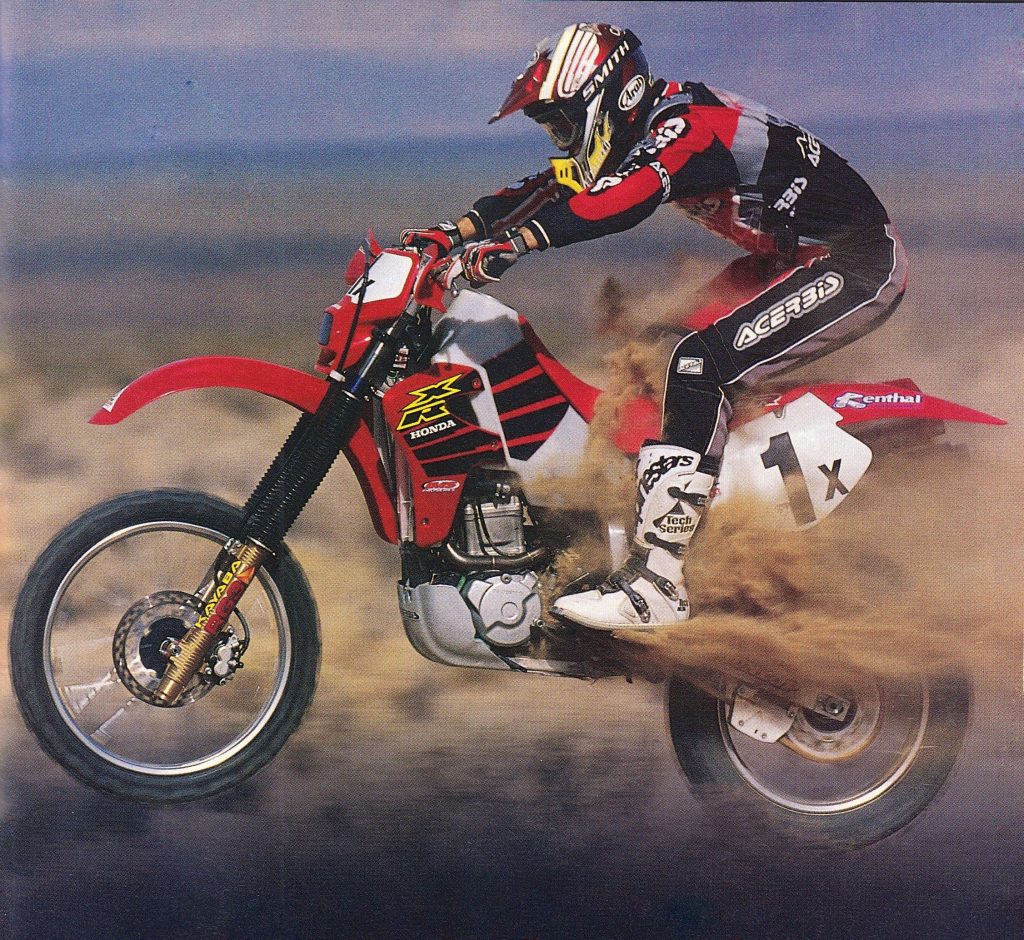

While the XR650R could be fun on a motocross course, it was far more at home in its natural environment hitting warp speed across the desert. Here Honda’s Baja ace Johnny Campbell pilots a works version of the new XR to victory. Photo Credit: Honda

While the XR650R could be fun on a motocross course, it was far more at home in its natural environment hitting warp speed across the desert. Here Honda’s Baja ace Johnny Campbell pilots a works version of the new XR to victory. Photo Credit: Honda

On the trail, the all-new XR turned out to be exactly what most XR600R fans had wanted. Power was super smooth, with tons of grunt and none of the stalling and hiccupping that drove Yamaha’s four-stroke converts crazy. Power delivery was closer to KTM’s churning 520SX than Yamaha’s fire-breathing YZ426F with a very smooth crescendo of power that built up slowly as you twisted the throttle. There was no sudden hit or explosive blast of thrust, just a mountain of torque available at the twist of your wrist. Where Yamaha’s 426F revved quickly, hit hard, and pulled to the moon, the more leisurely XR took its time, hunted for traction, and then rocketed forward. It was significantly faster than the old XR600R but not as potent as a Husaberg 600, KTM 520SX, or YZ426F. In stock form, the XR was jetted lean, choked off, and muffled down. Stock gearing was tall as well with a top speed just shy of 100 MPH.

With all the restrictors in place the stock XR delivered a smooth, mellow, and incredibly wide powerband. There was tons of power on tap but its electric delivery made it very easy to control. The XR never hiccupped, lurched, or stalled, and was easy to start despite its massive displacement. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With all the restrictors in place the stock XR delivered a smooth, mellow, and incredibly wide powerband. There was tons of power on tap but its electric delivery made it very easy to control. The XR never hiccupped, lurched, or stalled, and was easy to start despite its massive displacement. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Thankfully, however, there was a lot more power to be found in Honda’s big red desert sled. In stock form, the XR’s 42mm intake manifold had an insert installed that reduced its size to 20.8mm. The stock muffler’s 40mm core was also choked down to a tiny 20mm in size. These changes made the EPA happy and kept the XR quiet but limited maximum performance. Knowing that many buyers wanted more than a big trail bike, however, Honda offered a factory “power up” kit that opened up the intake and exhaust. Once this was done and the bike was rejetted, the XR was louder but significantly more potent. The basic XR personality remained, but there was more juice on tap when needed. The bike was fast enough to race motocross, Hair and Hound, or in the woods. Engine braking was less noticeable than on the old XR, but the big 650 remained more traditional in its feel than the Yamaha thumpers. Vibration was virtually non-existent, and the motor was as pleasant and easy to ride as any massive four-stroke single could hope to be. Riders with large feet found the stock shifter a bit too short, but most riders praised the XR’s light clutch and excellent shifting feel. The transmission featured widely spaced gears, but the motor’s prodigious torque made that mostly a non-issue. Gear it up for Baja or down for Glen Helen and the XR’s flexible motor was equally at home. On a motocross track, most riders could just leave it in third and ride the whole track like it was a one-speed. Fast, fun, and stone-axe reliable, the XR’s 649cc SOHC mill was just the motor upgrade XR enthusiasts had been asking for.

The XR’s 46mm forks were tuned too softly for serious aerial work but they performed excellently off-road. Ultra-plush and well-damped, they gobbled up rocks and ruts with little effort while still offering enough resistance to provide sufficient control at speed. Photo Credit: Honda

The XR’s 46mm forks were tuned too softly for serious aerial work but they performed excellently off-road. Ultra-plush and well-damped, they gobbled up rocks and ruts with little effort while still offering enough resistance to provide sufficient control at speed. Photo Credit: Honda

On the chassis front, the new XR was equally impressive. Big weight and big power don’t often add up to off-road excellence but in the case of the all-new XR650R Honda mostly subverted that expectation. At a Honda-claimed 277 pounds, the new XR650R was six pounds heavier than the old XR600R, but the stouter chassis, less flexy suspension, peppier power, and slimmer ergonomics made the new machine feel lighter. Turning was surprisingly good for such a large machine and the XR generally went exactly where it was pointed. There was noticeably more flex to the 46mm conventional forks than with its inverted competitors, but it did not seem to adversely affect the machine’s turning. The combination of the soft suspension, hefty motor, strong engine braking, and aggressive geometry delivered a front end that stuck to the terra firma like glue. No one was going to mistake the XR650R for an RM125, but it was more agile than any 300-pound machine had a right to be.

Like the forks, the shock on the new XR delivered a smooth and well-controlled ride that favored comfort over motocross-level stiffness. Big whoops and serious jumps overwhelmed its stock settings, but for most off-road use it was an excellent damper. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Like the forks, the shock on the new XR delivered a smooth and well-controlled ride that favored comfort over motocross-level stiffness. Big whoops and serious jumps overwhelmed its stock settings, but for most off-road use it was an excellent damper. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Despite its hefty proportions the XR650R was an able handler. Turing precision was excellent, and the bike was admirably stable at speed. As long as you did not try to throw it around like a 125, the big XR was a ready and willing partner. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

Despite its hefty proportions the XR650R was an able handler. Turing precision was excellent, and the bike was admirably stable at speed. As long as you did not try to throw it around like a 125, the big XR was a ready and willing partner. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

Perhaps most surprising was the fact that the XR’s steering agility did not seem to hinder its high-speed stability. Fittingly for a machine designed to do 100 MPH across the desert, the big red machine was a bullet train once in motion. There was not even a hint of headshake, and it took an act of congress to knock the 650 off its line once it built up a head of steam. Jumping the XR was easy, but you felt the weight and gyroscopic effect of that big crank if you tried to make any sort of correction in the air. Big whips and wicked turndowns were not in the XR650R’s repertoire in 2000. Motocross tracks were not its natural environment, but as long as you did not cross rut or come up short, jumping the XR was a drama-free experience.

While the XR650R was happier in the great wide open it was capable of some impressive speed in the woods with a talented rider like 5-time GNCC champion Scott Summers at the controls. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the XR650R was happier in the great wide open it was capable of some impressive speed in the woods with a talented rider like 5-time GNCC champion Scott Summers at the controls. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

For most riders, the only concern when jumping the XR was its rather softly-tuned suspension. The forks and shock were set up stiff enough to handle high-speed sand whoops and the occasional natural jump, but big air was not their intended purpose. At slow speeds they were super plush, and riders praised their performance off-road. The forks and shock were supple enough to absorb rocks and roots while still offering enough firmness to keep the bike under control at speed. Big whoops and high-speed sand washes pushed the outer limits of the stock springs and damping but they never did anything weird or bottomed harshly. If you did intend to do a little cross-training on a motocross track then stiffer springs were a good investment, but overall, the XR’s stock suspension was excellent for its intended use.

The XR650R was far more than an impressive racer. Its comfort, capability, and reliable performance embodied everything that made the XR line legendary. Photo Credit: Honda

The XR650R was far more than an impressive racer. Its comfort, capability, and reliable performance embodied everything that made the XR line legendary. Photo Credit: Honda

On the detailing front, the all-new XR was excellent in most ways with only a few small gripes. Unlike some previous XRs, the kickstarter stayed where it was supposed to and did not try to flop out constantly. The lack of an electric starter was a bummer but at least the Honda was an easy starter. There was none of the YZ/WR’s annoying starting drill and all it took was a strong and smooth kick to get the XR humming. The grips, levers, throttle, and clutch were excellent in quality and feel. The bike was well thought out and easy to work on with uniform bolt selection and high-quality fasteners. The clutch offered a light pull and generally stood up to abuse well. The filter was easy to access and a piece of cake to clean or change. The brakes worked excellently with great power, superb feel, and trouble-free operation. In stock condition, the motor was absolutely bulletproof with many XR650Rs going well over 30k miles without a major rebuild. With XR650Rs in many markets outside the US being legal for the street it was clear that Honda designed the motor to last. The 650’s seat was less of a couch than the old 600’s, but riders still rated it above all the Honda’s competitors in comfort. The new ergonomics were much better for standing but “sit down” riders found it took a bit to get used to the more modern layout. With nearly 50 horsepower on tap, the big XR was plenty powerful even in stock condition but its super smooth delivery and tremendously wide powerband made it about the easiest to ride 50 horsepower machine in existence. As long as you were tall enough to climb on and strong enough to muscle its 300 pounds, the XR was a piece of cake to control.

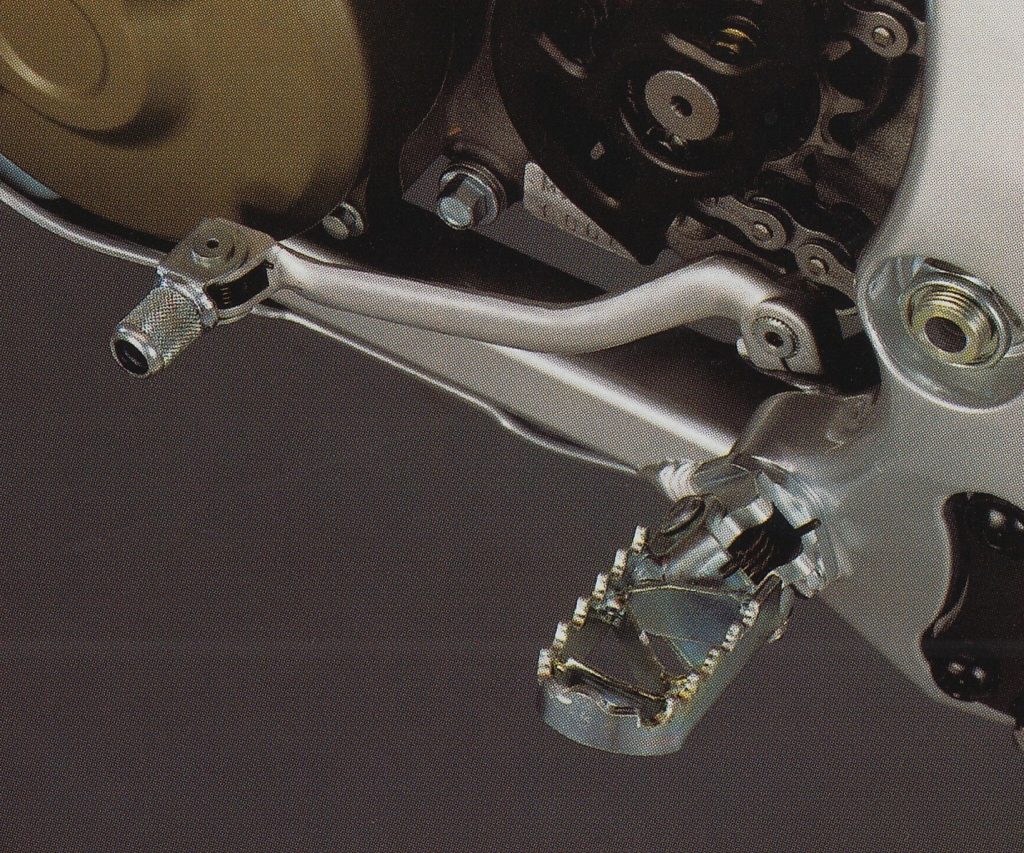

While most of the XR’s components were of impeccable quality, its footpegs were universally panned for the short and narrow profile. Photo Credit: Honda

While most of the XR’s components were of impeccable quality, its footpegs were universally panned for the short and narrow profile. Photo Credit: Honda

First up on the demerits side had to be the bike’s weight, which was an issue regardless of how well it hid its tonnage. The XR was almost 30 pounds heavier than a WR426F, a machine already well-known for its hefty proportions. Even more disappointing was the fact that the new machine was heavier than the old XR despite the new bike’s aluminum frame and lack of an electric starter. The 650R was well-mannered for such a big bike, but if things got out of sorts there was no denying Sir Isaac Newton and his three laws of motion. Ditching the massive stock exhaust and EPA froof helped, but the bike was going to remain heavy unless you were willing to throw cubic dollars at it for Ti parts and accessories. One of those upgrades was likely to be the pegs, which were disappointingly small and narrow. Upgrading to a titanium IMS alternative shaved 2 ounces and provided good insurance for your ankles. The stock steel bars were also an item crying to be upgraded to improve strength and shave a few ounces. The stock graphics were very attractive, but easily damaged by knee braces. Aside from its weight and these small quibbles, the XR650R was a very well-thought-out and finished machine.

Honda’s XR650R was a bit of a throwback in a four-stroke world that was rapidly changing. Big, mellow, and built for maximum durability, the Super XR delivered the type of comfort and performance that had made the XR name legendary.

Honda’s XR650R was a bit of a throwback in a four-stroke world that was rapidly changing. Big, mellow, and built for maximum durability, the Super XR delivered the type of comfort and performance that had made the XR name legendary.

In the end, Honda ended up making exactly the machine they had set out to create. Many riders had hoped Honda would deliver a competitor to the YZ/WR400F, but Big Red had other plans for their new Super XR. Honda designed the XR650R to conquer Baja and that is precisely what it would do. They never envisioned it as a motocross machine despite the temptation to take it to the track. Reliability, ease of service, and comfort were just as important as outright performance in the crafting of the 2000 XR650R. In 2005, Honda enthusiasts would finally get the true competitor to the Yamaha thumpers in the form of the CRF450X. Eventually slowing sales and the CRF would push the XR650R into retirement. Over its seven-year run, the XR650R enjoyed a loyal following, but that fan base never brought the XR the type of success enjoyed by the sexier CRFs. Honda’s last true XR rode off into the desert in 2007, signaling the end of one of the most storied lines of machines in the sport’s history.