For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s Nuclear Red CR125R for 1992.

For 1992, Honda dialed up a list of modest updates to go with a bold new color scheme for their CR125R. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1992, Honda dialed up a list of modest updates to go with a bold new color scheme for their CR125R. Photo Credit: Honda

In serious 125 class racing, horsepower is not just the most important thing, to many racers it is the only thing. In the heyday of 125 racing riders were willing to put up with all sorts of other faults in their machines if it meant their mount had an advantage in the all-important horsepower wars. Riders on 250s and 500s could afford to be picky about handling and suspension but hardcore tiddler pilots knew that in the 125 class, those things were luxuries not necessities.

The majority of Honda’s R&D budget for 1992 went to an all-new CR250R. Photo Credit: Honda

The majority of Honda’s R&D budget for 1992 went to an all-new CR250R. Photo Credit: Honda

Throughout the late eighties and early nineties, this was the key to Honda’s hold on the 125 division. The red 125 machines were often flawed in many ways, with vicious headshake, cranky suspension, and difficult-to-use powerbands that rewarded aggression and penalized timidity in equal measures. Starting in 1987, the CR125R became the king of high-RPM performance. The red tiddlers shrieked on top and pulled with authority well past the point where the green, yellow, and white competition were begging for another shift. This made the CRs the darling of the pro class, where riders prized endless revs and did not bother themselves with concerns like low-end torque and suspension compliance. These riders kept the motor pinned and floated over obstacles that riders of lesser talent slammed into. For experts and aspiring pros, the CR125R was the best platform for building a career in the 125 division.

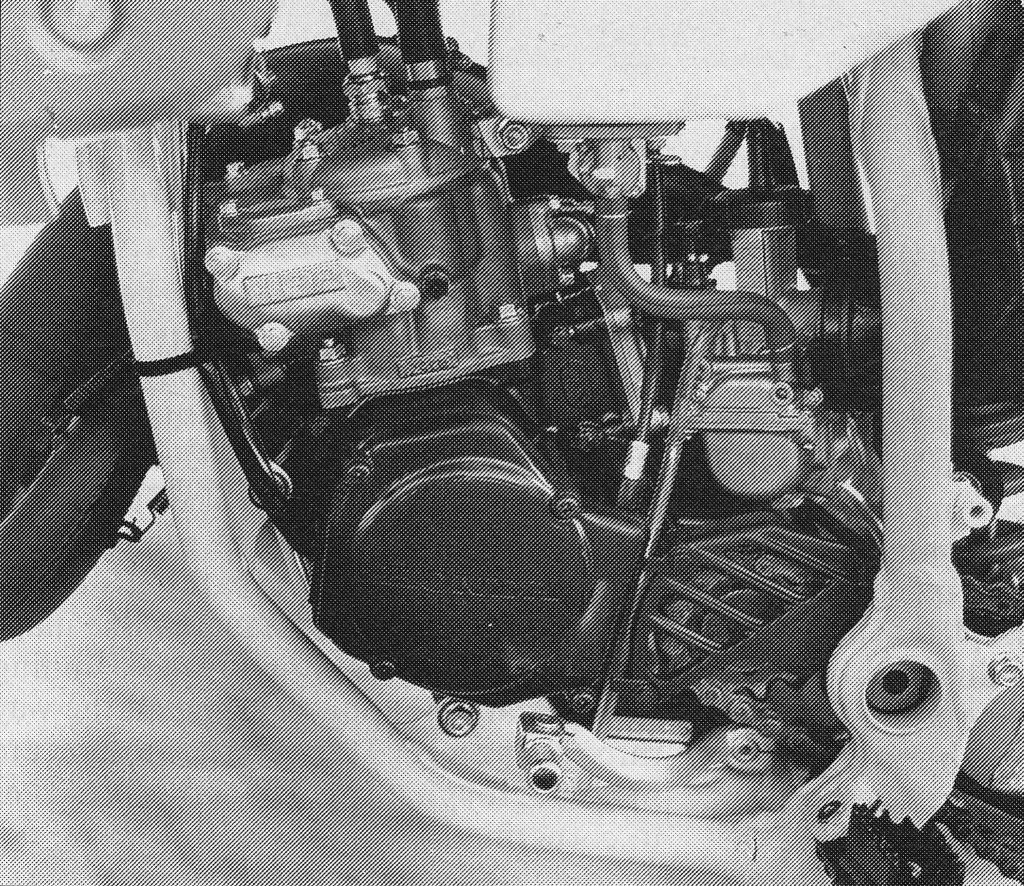

Minor motor updates for 1992 included the switch to a flat-top piston (right). Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Minor motor updates for 1992 included the switch to a flat-top piston (right). Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While throttle jockeys loved the CRs for their endless top-end pull, average Joes often found Honda’s 125s in this era less endearing. The pro-focused powerband lacked low-end torque and demanded a total commitment to keep the red machine from falling off the pipe. Its stock suspension was harsh and unless you had the speed of Mike Kiedrowski it beat you to death in short order. Machines like Suzuki’s RM125 and Kawasaki’s KX125 often bested the CR in shootouts despite their more modest power outputs.

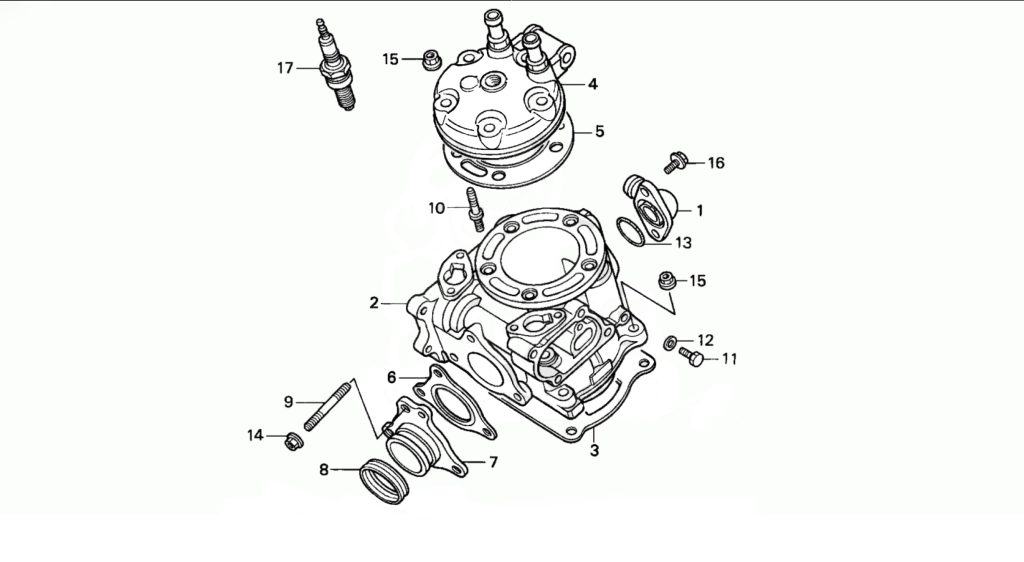

A new top end for 1992 included a reshaped head and revised cylinder porting. Photo Credit: Honda

A new top end for 1992 included a reshaped head and revised cylinder porting. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1991, this was once again the story of Honda’s CR125R. The CR’s 125cc mill continued to produce the most top-end in the class, but its lack of low-end response and unique combination of Showa forks and a Kayaba shock failed to impress. Riders loved the CR’s sharp turning but its penchant for violent headshake was disconcerting to some and flat terrifying to others. Pros continued to love the Honda for its endless pull, but most of the motocross press felt the superior suspension and broader power of the KX125 gave it the edge for the majority of 125-class riders.

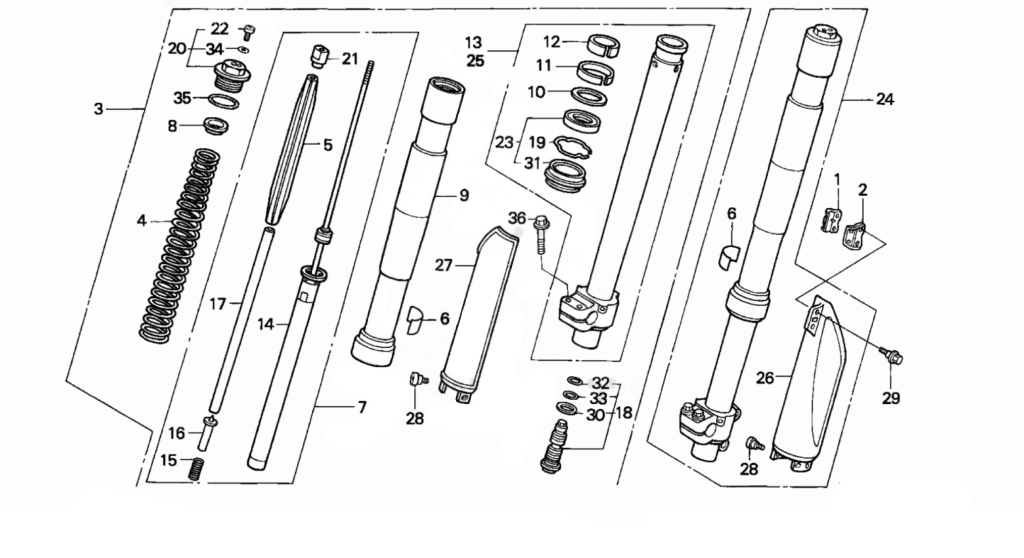

An all-new Showa fork for 1992 reduced the size of the lower tubes by 2mm, added a triple-stage taper to the upper clamping area, and introduced external adjustments for rebound damping. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new Showa fork for 1992 reduced the size of the lower tubes by 2mm, added a triple-stage taper to the upper clamping area, and introduced external adjustments for rebound damping. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1992, Honda’s big news was in the 250 class, where their championship-winning CR250R was due for a major update. Everything about the old machine was retired in favor of a clean sheet design that was faster, slimmer, and considerably brighter in appearance. Emblazoned in Honda’s all-new “Nuclear Red”, the redesigned CR250R was a Supercross-focused machine with razor-sharp turning, revamped suspension, and a blisteringly fast motor.

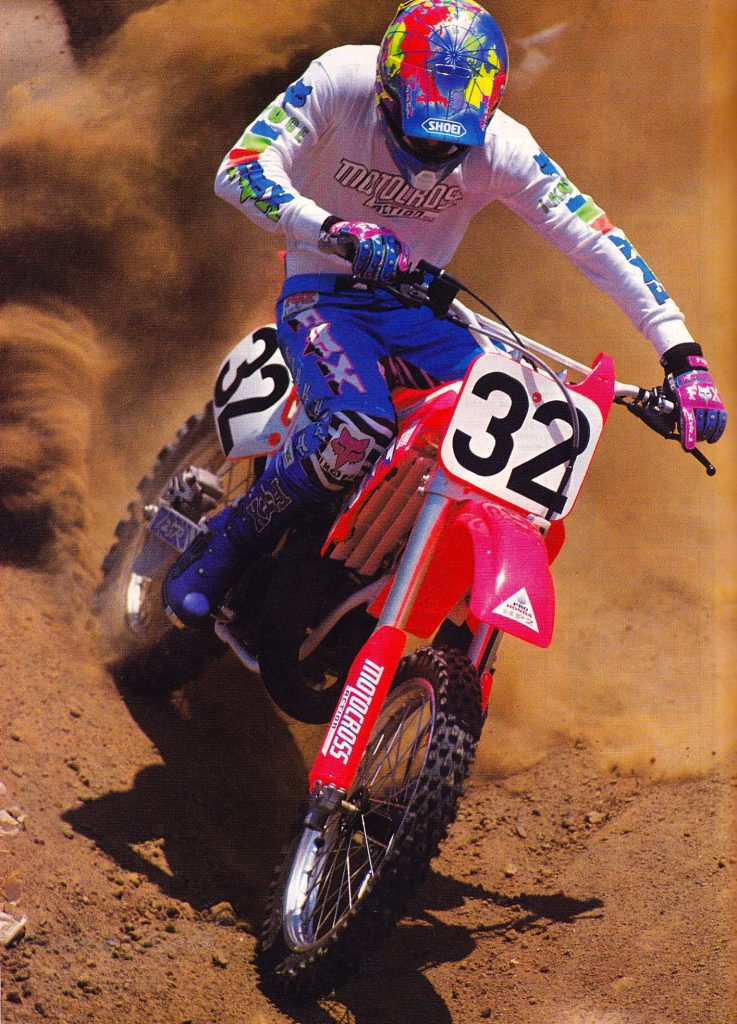

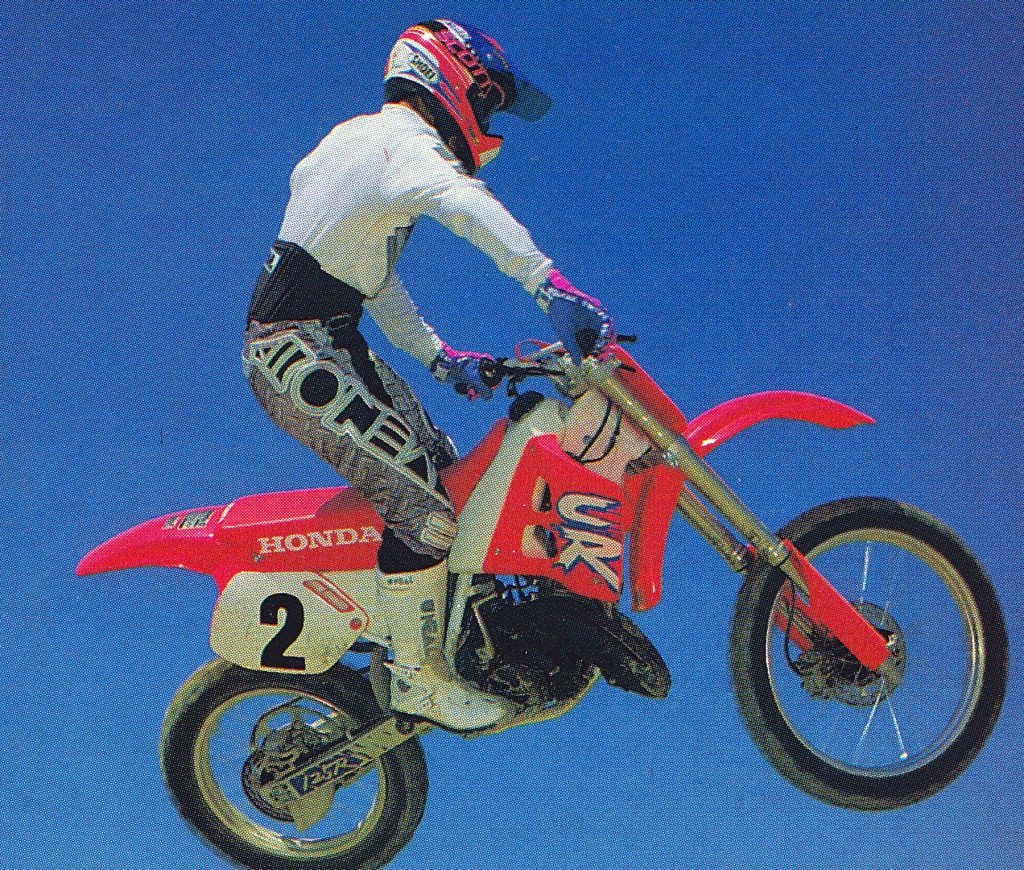

Honda’s top gun on the CR125R in 1992 was Peak Pro Circuit’s Jeremy McGrath. In 1991, McGrath scored his first 125 Supercross title on the blue and white CRs and he followed that up in 1992 with a second straight West Coast Supercross title. Photo Credit: Chris Hultner

Honda’s top gun on the CR125R in 1992 was Peak Pro Circuit’s Jeremy McGrath. In 1991, McGrath scored his first 125 Supercross title on the blue and white CRs and he followed that up in 1992 with a second straight West Coast Supercross title. Photo Credit: Chris Hultner

With the CR250R taking the lion’s share of the R&D dollars for 1992, the CR125R was left with a rather modest list of updates aimed at improving its overall competitiveness. Like the 250, the 125 received a dramatic color pallet update that made it look far newer than it was. The plastic molds were all a carryover from 1991 but the new neon red plastic, white tank, and white airbox gave the old bodywork a striking new appearance. Honda claimed the move was done to allow their bikes to stand out more on TV and their mission was certainly accomplished. The new color practically glowed under the lights and gave the red machines a far bolder appearance than the old “Flash Red”.

A new shock for 1992 added revised valving and an additional 0.4 inches of suspension travel. Photo Credit: Australian Dirt Bike

A new shock for 1992 added revised valving and an additional 0.4 inches of suspension travel. Photo Credit: Australian Dirt Bike

In addition to the new color scheme, the 1992 CR125R received a substantial update to its suspension. Starting in 1989, Honda’s reputation for suspension excellence had taken a serious downturn. After two years of fork dominance, the ’89 CRs shocked consumers with baffling settings and grim performance. A move to inverted components in 1990 only exacerbated their harsh feel with most riders listing the forks as the largest chink in the CR125R’s armor. In 1992, Honda decided to bring back a bit of compliance to the CR’s front end by reducing the diameter of the lower tubes by 2mm and adding a three-staged taper to the clamping area. The forks remained manufactured by Showa and featured softer springs and revised damping that Honda hoped would bring back a bit of plushness to the harshest front end in motocross. Travel was increased by 0.2 inches and a 17-position rebound adjuster was added to allow for a more precise tuning of the front end’s performance. Like in 1991, an external adjuster allowed for 14 selectable settings for compression damping control.

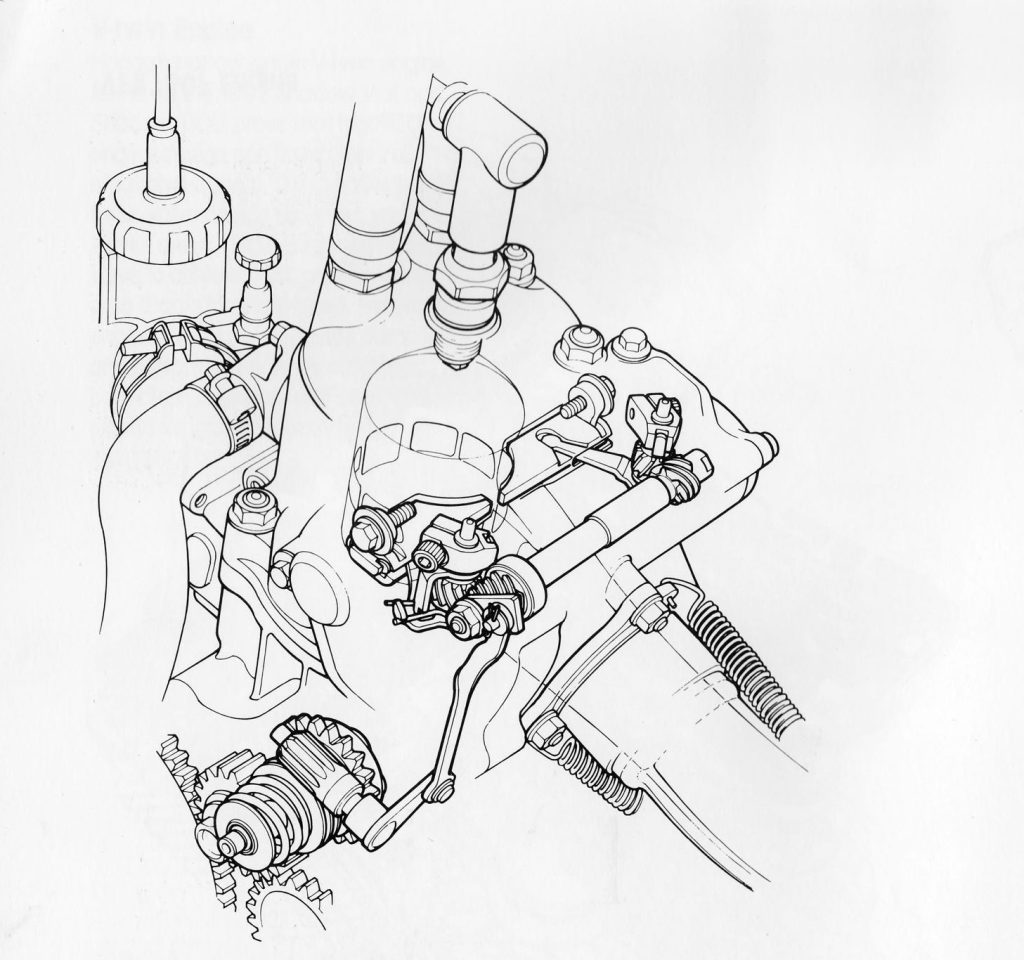

The CR125R did not adopt the CR250R’s all-new power valve system for 1992. Instead, it continued to feature the Honda Power Port design it had employed since 1990. Photo Credit: Honda

The CR125R did not adopt the CR250R’s all-new power valve system for 1992. Instead, it continued to feature the Honda Power Port design it had employed since 1990. Photo Credit: Honda

Paired with the forks was an all-new clamp that featured 2mm of increased offset and a larger clamping area to improve front end feel. The CR’s frame remained largely unchanged but modifications to the clamps and suspension added up to a 3mm reduction in wheelbase, a 2mm decrease in trail, and a 0.25 degree increase in rake. Honda claimed these changes would deliver improved turning and increased stability in the whoops. The footpegs were repositioned rearward 11mm as well to improve weight balance.

For skilled riders the CR’s horsepower advantage outweighed its many other deficiencies in 1992. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For skilled riders the CR’s horsepower advantage outweighed its many other deficiencies in 1992. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the rear, the CR125R continued to use Kayaba as its suspension provider. For 1992, Honda added an additional 0.4 inches of travel and all-new valving designed to improve the little Honda’s lackluster performance. The linkage and swingarm remained unchanged from 1991. The new damper featured 12 inches of travel to go with its 22 compression and 20 rebound damping adjustments.

The CR’s revamped motor for 1992 did not run much differently than it had in 1991. There was very little power below the midrange and the bike required skill and commitment to keep it in the meat of its high-strung powerband. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The CR’s revamped motor for 1992 did not run much differently than it had in 1991. There was very little power below the midrange and the bike required skill and commitment to keep it in the meat of its high-strung powerband. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the motor front, the CR was largely unchanged for 1992. Of all the CR’s assets, this was certainly its greatest and it was clear Honda was not looking to upset its many horsepower devotees. Instead of chasing more peak ponies, Honda went looking for improved response in 1992. This had been the CR motor’s largest weakness since its major revamp in 1987 and that lack of grunt was only made more glaring when the Honda was ridden back-to-back against super snappy machines like Suzuki’s RM125. Once it was on the pipe, the CR was wicked fast, but below the upper midrange, the Honda was a wasteland of bog.

The CR’s handling favored turning over stability but it behaved well at speed as long as it was hooked up and on the gas. It was only when it was time to slow down that the Honda’s chassis developed a bad case of the shakes. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

The CR’s handling favored turning over stability but it behaved well at speed as long as it was hooked up and on the gas. It was only when it was time to slow down that the Honda’s chassis developed a bad case of the shakes. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

To add a bit of grunt, Honda dialed up a new top end for 1992 that featured a reshaped head and new flat-top piston. The new combustion chamber boosted compression slightly from 8.9:1 to 9.1:1 and was paired with a new cylinder that featured reshaped exhaust valves for improved flow. The updated motor continued to use the guillotine-style Honda Power Port (HPP) variable exhaust valve introduced on the 125 in 1990. In a nod to improved durability, the crank and connecting rod featured a new heat treatment as well for 1992.

The Honda’s new 43mm Showa forks proved to once again be a disappointment in 1992. They were poorly set up from the factory and harsh in action. With stiffer springs, some oil fiddling, and clicker spinning they could be improved but their action was never going to offer the comfort of the classes’ top suspension contenders. Photo Credit: Honda

The Honda’s new 43mm Showa forks proved to once again be a disappointment in 1992. They were poorly set up from the factory and harsh in action. With stiffer springs, some oil fiddling, and clicker spinning they could be improved but their action was never going to offer the comfort of the classes’ top suspension contenders. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1991, some CR125Rs had suffered from an annoying pop at high RPM and Honda made a few changes for 1992 aimed at exorcising the pop and improving throttle response. First up was a new reed valve that reduced the size of the intake by 5mm. The jetting was also revised in the 36mm flat-slide Keihin PJ carburetor to work with the new intake and revamped top end. The airbox, expansion chamber, and silencer remained unchanged from 1991.

Pin it to win it: Carving wicked arcs and throwing massive roost were the CR’s stock and trade in 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Pin it to win it: Carving wicked arcs and throwing massive roost were the CR’s stock and trade in 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

New wheelsets for 1992 saved nearly a pound of unsprung weight and an all-new front braking system improved the feel and added additional adjustability. The new brake featured a shorter lever with adjustments for reach as well as a stronger caliper with increased rigidity and a more aggressive lever ratio. Kevlar-reinforced brake lines provided a firm and predictable feel at the lever. Honda’s excellent rear disc remained unchanged for 1992 aside from a switch to holes instead of slots for cooling the rotor.

While the action of the CR’s Kayaba shock was far from perfect, it was better sorted than its disappointing front forks. Overall action was decently controlled but it lacked the plushness and comfort of other top performers in the class. Photo Credit: Honda

While the action of the CR’s Kayaba shock was far from perfect, it was better sorted than its disappointing front forks. Overall action was decently controlled but it lacked the plushness and comfort of other top performers in the class. Photo Credit: Honda

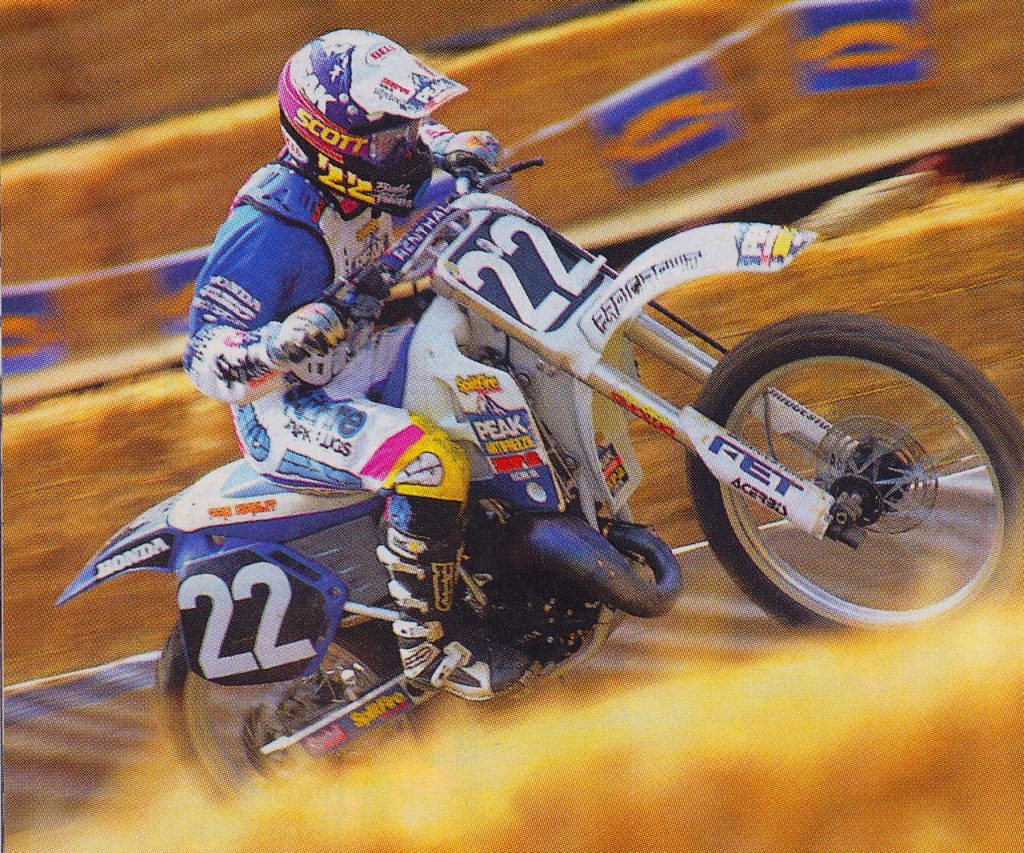

Tennessee’s Mike Brown was one of Pro Circuit’s young guns on the CR125 in 1992. Unfortunately for Brown, his results in 1992 would prove disappointing and he would be released from the team only to return nine years later and deliver Pro Circuit a 125 National Motocross title in 2001. Photo Credit: Chris Hultner

Tennessee’s Mike Brown was one of Pro Circuit’s young guns on the CR125 in 1992. Unfortunately for Brown, his results in 1992 would prove disappointing and he would be released from the team only to return nine years later and deliver Pro Circuit a 125 National Motocross title in 2001. Photo Credit: Chris Hultner

On the track, the 1992 Honda CR125R delivered a unique 125 experience. No other machine in the class ran or felt like the CR and this made it a somewhat polarizing machine. As in the past, the CR’s motor was wicked fast, but its powerband was pro-focused and demanding. There was virtually no power below the midrange and merely twisting the throttle out of turns was not enough to get the CR up and going. Unlike the RM and KX, the Honda required a lot of throttle and a slip of the clutch to get past this flat spot down low and this made it trickier to ride than the more friendly powerbands of the yellow, green, and magenta competition. Once it was past this low-end lull, however, it was time to strap in for a rocketship ride to the front. From the midrange on up, nothing in the class was as fast as Honda’s Nuclear Red missile. Once on the pipe, the CR barked to attention and shrieked to a top-end hook that left its competition in the dust. As in the past, there remained an annoying pop on overrev but this did nothing to hinder the CR’s competitiveness on the track. The small motor updates for ’92 yielded a slightly more robust hit in the midrange, but the motor’s feel remained largely unchanged from 1991. Its clutch was smooth and durable, and its transmission was flawless. For pros and talented intermediates, it was the perfect 125 motor.

The CR’s case-reed motor provided by far the most top-end power in the class but its lack of low-end torque made it tricky for riders of lesser skill and experience. It was prone to falling off the pipe between gears and required the rider to keep up their momentum in turns and always be ready with a quick slip of the clutch to get the high-strung Honda back up and singing. Photo Credit: Honda

The CR’s case-reed motor provided by far the most top-end power in the class but its lack of low-end torque made it tricky for riders of lesser skill and experience. It was prone to falling off the pipe between gears and required the rider to keep up their momentum in turns and always be ready with a quick slip of the clutch to get the high-strung Honda back up and singing. Photo Credit: Honda

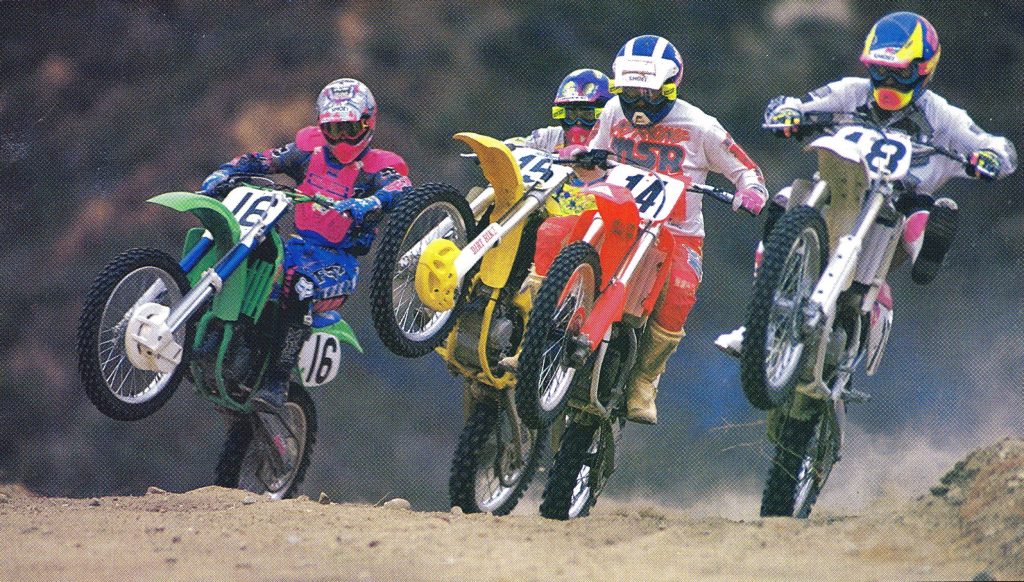

Only Suzuki’s RM125 had any hope of outgunning the CR125R to the inside line in 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Only Suzuki’s RM125 had any hope of outgunning the CR125R to the inside line in 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

As great as the engine was, however, it was not the best motor for everyone. If you did not have the skill to keep it pinned, then the CR could be a frustrating machine. Its lack of torque made it very tricky to manage if the track was slick and it tended to fall off the pipe if you shifted too early or selected the wrong gear out of a tight turn. Once it was off the pipe, it took major clutch slipping and precious seconds to get the CR back to a full boil. Gearing the bike down was the easiest way to Band-Aid this lack of torque but the CR was never going to be as easy to ride as Suzuki’s ultra-responsive RM125.

The CR125R had the power to put Jeremy McGrath at the front in 1992 but his outdoor fitness was not yet up to keeping him in the number one spot. It would take MC a few more years before he was ready to finally capture his first outdoor National title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The CR125R had the power to put Jeremy McGrath at the front in 1992 but his outdoor fitness was not yet up to keeping him in the number one spot. It would take MC a few more years before he was ready to finally capture his first outdoor National title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the handling front, the CR remained true to the principles Honda had been embracing since the major 1983 redesign of their lineup. This meant sharp turning at the expense of stability. The subtle changes to the geometry for 1992 did very little to change the CR’s personality and it remained a corner carver beset by occasional fits of schizophrenic headshake. Front-end traction was excellent and only Suzuki’s razor-sharp RM had any hope of outdicing the red machine to the inside line. Under power, the CR was solid and predictable, but some riders struggled with a bit of oversteer once the CR’s motor caught fire and kicked in the afterburners. Exiting slick turns could be tricky for riders unaccustomed to the Honda’s potent power delivery. Once up to speed, the CR was fairly stable but when it was time to slow down the Honda developed a serious case of the twitches. Under braking in the rough, the front end danced and oscillated like a was waving to fans along the fence. If you were tired, pumped up, or thinking about the cute girl that the front wheel was waiving at, then it could snap side-to-side hard enough to rip your hands clean off the bars. Unlike the RM, which felt tensed up and unplanted all the time, the CR seemed just fine until it wasn’t. This Jekyll and Hyde personality terrified riders unacquainted with the Honda’s handling peccadillos but was generally accepted by devotees of the red machines. The CR’s jumping manners remained excellent and the Honda was happy to be whipped, tossed, and thrown around in the air. Its powerful motor made big doubles no trouble as long as the leap was not right out of a turn. Here, the RM and KX had an advantage with their easier-to-manage and faster-building power delivery.

The CR125R was an able leaper in 1992 with excellent ergonomics, a light feel, and plenty of boost for conquering serious gaps. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The CR125R was an able leaper in 1992 with excellent ergonomics, a light feel, and plenty of boost for conquering serious gaps. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the suspension front, the CR was once again a disappointing performer. This had been the red 125’s most glaring flaw the previous three years and it again proved to be the machine’s undoing in the minds of many. The new 43mm Showa forks were slightly more fluid than the old 45mm units but most riders felt they were still the worst forks in the 125 class. In stock condition, they were undersprung and underdamped, with a harsh feel that was ever-present on every bump and whoop. They hung down in the stroke and hammered the rider’s wrists in the rough. The addition of rebound damping control for ’92 made them easier to dial in, but no amount of clicker spinning was enough to exorcise their harsh action. Anyone above 150 pounds was likely to want stiffer springs and a trip to a knowledgeable suspension tuner was a wise investment for anyone serious about racing the CR.

After several years on Team Suzuki former mini star Buddy Antunez made the jump to Peak Honda in 1992. Budman would backup McGrath out west racing to several podiums and second overall in the 125 West Coast Supercross standings.

After several years on Team Suzuki former mini star Buddy Antunez made the jump to Peak Honda in 1992. Budman would backup McGrath out west racing to several podiums and second overall in the 125 West Coast Supercross standings.

In the rear, the CR’s Kayaba shock was better sorted than its front forks. The shock was far less plush than the ultra-comfy Kawasaki, but most riders felt it was raceable without any serious modification. The overall action was slightly choppy, and the bike was prone to the occasional hop in the rough, but it took big hits well and rarely did anything scary. Even though its action was far from grim, most testers still rated the CR’s shock behind its rivals in performance. Fast guys probably needed a stiffer spring but for most racers, it was usable without sending it out for a re-valve.

Unless you made a mistake, no other 125 was going to outgun the CR125R to the first turn in 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Unless you made a mistake, no other 125 was going to outgun the CR125R to the first turn in 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the detailing front, the CR was excellent in some ways and surprisingly disappointing in others. For years, Honda had built its reputation on quality and reliability but more than a few CR125Rs in ’92 suffered from cracked and broken pistons. Many riders blamed the new flat-top piston and advocated swapping back to the 1991 model’s piston and head to prevent detonation and increase reliability. The stock reeds were known to chip after a few months of use, and it was a good idea to replace them with an aftermarket option at the first motor teardown. The top tank on the radiators was also known to leak and it was a good idea to have it reinforced. The popping on the top end was still present and annoying but it did not seem to affect performance. The CR often exhibited a bog when landing from big jumps and in the whoops and the fix for this was to copy the factory team and add an additional pair of vent hoses to the carb that prevented vapor locking if fuel made it into the overflow. This was a trick that Jean-Michel Bayle’s mechanic Cliff White had discovered and it would become standard equipment on all two-strokes by the mid-nineties. The HPP system worked well at making big power, but it continued to be a real pain to service. Its complicated series of valves, springs, and levers was easily gummed up and difficult to work on. If you neglected it or got its reassembly wrong, then the CR’s power took a serious dive. If you were going to be a CR owner, it was important to get this routine down or make sure to ask your dad really nicely when it was time to service the top end. As in the past, clutch and transmission action were excellent and the CR delivered the most reliable performance in the class.

Honda’s new Nuclear Red color proved polarizing to many in 1992. While it certainly stood out more than the old Flash Red, it faded quickly and looked worn out and tattered far faster than the previous shades Honda had employed. Additional pigment added in 1993 would lessen the 1992’s pinkish tint and improve the plastic’s resistance to fading once it was exposed to the sun. Photo Credit: Le Big

Honda’s new Nuclear Red color proved polarizing to many in 1992. While it certainly stood out more than the old Flash Red, it faded quickly and looked worn out and tattered far faster than the previous shades Honda had employed. Additional pigment added in 1993 would lessen the 1992’s pinkish tint and improve the plastic’s resistance to fading once it was exposed to the sun. Photo Credit: Le Big

The CR’s new Nuclear Red bodywork was polarizing at first but most riders got used to the new look after a few months. What did not age well, however, was the pigment Honda used for the new plastic. It started as a neon red on the showroom floor but quickly transitioned to a shade of salmon pink once it spent a little time in the elements. It also showed ugly white lines when bent and generally looked beat far faster than any other bodywork in Honda’s history. Aside from the fading, however, the bodywork was excellent in quality, with perfect fitment and none of the cracking or stripping of mounting hardware seen on many of the CR’s rivals. The bars, seat, grips, levers, and switchgear were also excellent in quality and considered the standard of the class in durability and comfort. The salmon CR may have looked a bit beat, but it continued to feel tight long after the competition was ratty and rattling.

An all-new front binder for 1992 increased Honda’s stranglehold on braking performance. Photo Credit: Le Big

An all-new front binder for 1992 increased Honda’s stranglehold on braking performance. Photo Credit: Le Big

The new brakes were works bike-strong and bulletproof in action. They offered the most power, the best feel, and the least need for maintenance in the class. The new adjustable shorty lever allowed for a wide range of hands, and no one ever complained about the CR’s stoppers. From the factory, the CR came with very little grease in its bearings, and it was a good idea to tear it down and pack the linkage and steering head with good-quality grease if you planned on keeping the action of its moving parts consistent.

In the end, your opinion of the 1992 Honda CR125R came down to your priorities. If speed was your thing, then it was an appealing choice. Its blistering top-end and reputation for winning made it the machine to have for experts and aspiring pros. They were never going to miss the motor’s lack of low-end and most likely already had a suspension tuner on speed dial. For them, a fast motor was far and away a 125’s biggest draw, and no other machine in 1992 was as fast as Honda’s nuclear-powered CR125R.

Damn the torpedoes: In the late eighties and early nineties nothing in the 125 class was as fast as Honda’s high-RPM hauler. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Damn the torpedoes: In the late eighties and early nineties nothing in the 125 class was as fast as Honda’s high-RPM hauler. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For those of lesser talent and experience, however, the CR’s brand of hyper handling, harsh suspension, and pin-it-to-the-stops power made the red machine a less clear choice. Suzuki’s RM125 turned sharper, felt lighter, and offered a far less-demanding powerband. Kawasaki’s KX125 lacked the motor pizzazz of the red and yellow machines but made up for it with roomy ergonomics and magic carpet suspension. Both machines were far easier to ride than the Honda and if you were honest about your skill and talent, they may have made a better selection if a National number was not in your future.

Honda’s CR125R was the top pick for expert riders in 1992. Its violent headshake, unrefined suspension, and stratospheric powerband made it less appealing than Suzuki’s more friendly RM125 to many, but if you had the skill to keep it dialed to eleven, then the red rocket was your ticket to the winner’s circle. Photo Credit: Honda

Honda’s CR125R was the top pick for expert riders in 1992. Its violent headshake, unrefined suspension, and stratospheric powerband made it less appealing than Suzuki’s more friendly RM125 to many, but if you had the skill to keep it dialed to eleven, then the red rocket was your ticket to the winner’s circle. Photo Credit: Honda

Boldly colored, wickedly fast, and diabolically forked, the 1992 Honda CR125R was an alluring but flawed machine. Its motor offered National-caliber speed, but it took National-caliber talent to make the most of its potential. Its peaky power, lack of suspension finesse, and violent fits of headshake made it a hard sell to many, but for those with the skill to keep it singing and the strength to pound through the bumps, it was the ultimate 125 weapon in 1992.