For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki’s all-new 1986 KX80.

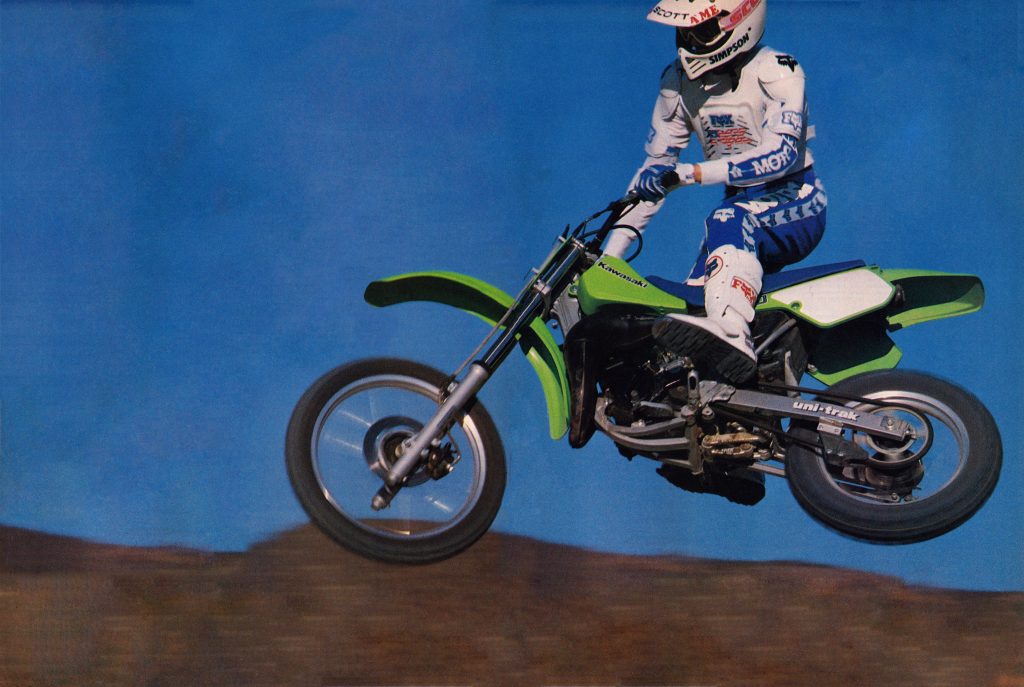

In 1986, Kawasaki took a huge gamble by completely redesigning the most dominant mini in motocross. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1986, Kawasaki took a huge gamble by completely redesigning the most dominant mini in motocross. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the early 1980s, very few machines in motocross were as dominant as Kawasaki’s KX80. Starting with the 1982 model year, Kawasaki’s mini missile was the class of the 80cc field. With its long-travel Uni-Trak rear suspension and broad power, the little Kwacker made going fast easy for the aspiring Jeff Wards of the mini division. In 1983, Kawasaki upped the ante with an all-new chassis and trick liquid-cooled powerplant that further cemented their hold on the 80cc division. The water-pumping KX mini barked out of the hole and blasted into a muscular midrange that left its red and yellow competition in the dust.

The color of money: From 1982 through 1985, no machine in motocross was as universally praised as Kawasaki’s blisteringly fast KX80. Its awesome power plant was the class of the field and a major reason the mini class turned green in the early 1980s. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The color of money: From 1982 through 1985, no machine in motocross was as universally praised as Kawasaki’s blisteringly fast KX80. Its awesome power plant was the class of the field and a major reason the mini class turned green in the early 1980s. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Over the next two seasons, the green meanie’s competitors all took swings at the champ, but none of them were able to replicate the KX’s awesome combination of blistering motor performance and ease of use. The KX’s broad powerband made it easy to ride, and its strong midrange satisfied riders from novice to pro. In 1985, many pilots felt the all-new Honda CR80R handled better and offered better suspension than the KX80, but its drum front brake and ATAC motor were still no match for the Kawasaki’s powerful front disc and brawny motor performance. The competition was closing the gap, but the green King still reigned in 1985.

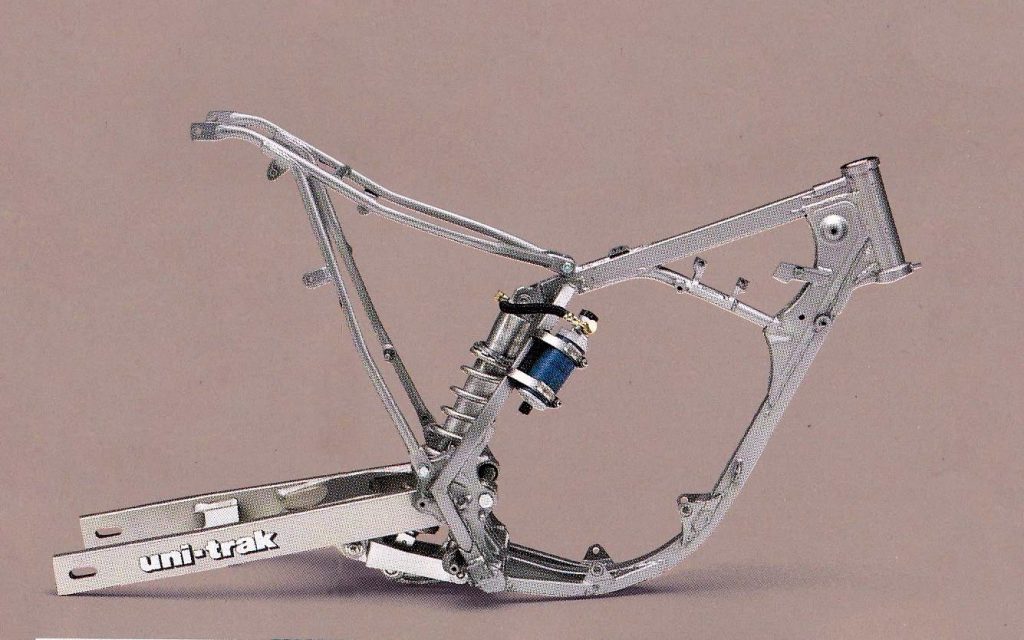

Give the dog a bone: Introduced in 1980 on the full-sized KX models, Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak was the first linkage suspension system to make it to production from the Japanese. In 1986, Kawasaki finally retired their original “dog bone” linkage design for a Honda-style bottom link that saved weight, improved handling, and simplified component packaging. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Give the dog a bone: Introduced in 1980 on the full-sized KX models, Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak was the first linkage suspension system to make it to production from the Japanese. In 1986, Kawasaki finally retired their original “dog bone” linkage design for a Honda-style bottom link that saved weight, improved handling, and simplified component packaging. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1986, Kawasaki took a substantial gamble by completely scrapping the mini machine that had ruled the 80cc roost for the past three seasons. First up on the list of changes for 1986 was an all-new chassis that moved away from the original “dog bone” Uni-Trak linkage Kawasaki had been using on its motocross machines since 1980. The updated design moved to a Honda Pro-Link style “bottom link” configuration that allowed the engineers to reduce weight, lower the machine’s center of gravity, and improve airflow to the motor by enlarging the airbox and repositioning the intake tract. The new frame remained crafted out of steel but moved to a square-section tubing that Kawasaki claimed increased resistance to flex under heavy loads. The overall size of the chassis was larger for 1986, with an eye toward accommodating larger mini pilots. Chassis geometry was all-new, and for the first time, the frame featured a fully removable rear subframe to allow easy shock access.

An all-new frame for 1986 repositioned the rear linkage below the swingarm and moved to a square-section tubing to increase strength. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

An all-new frame for 1986 repositioned the rear linkage below the swingarm and moved to a square-section tubing to increase strength. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Along with the larger frame, Kawasaki dialed up all-new bodywork that slimmed and flattened out the riding compartment on the green machine. The new tank was slightly smaller with a narrower profile and a redesigned radiator shroud that tucked in closer to the tank. The new seat was longer, taller, and flatter on top to allow easier rider movement and provide a bit more room for taller pilots. The redesigned side plates were a bit shorter and eliminated the ’85 model’s hand holds, but they did offer slightly more room for numbers. The rear fender was all-new as well, with a larger profile to provide a bit more protection from roost. The overall styling of the bodywork remained similar to 1985, with the most dramatic visual cue being the repositioning of the “KX” logo from the sides to the top of the seat for ’86.

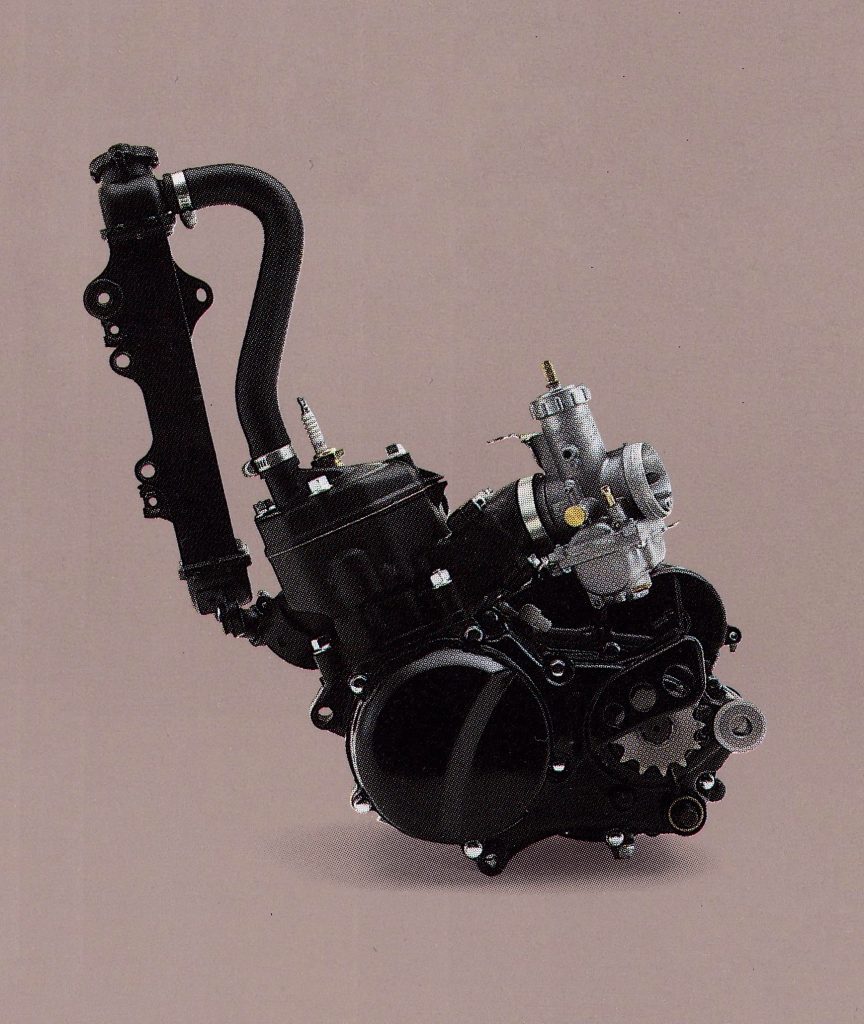

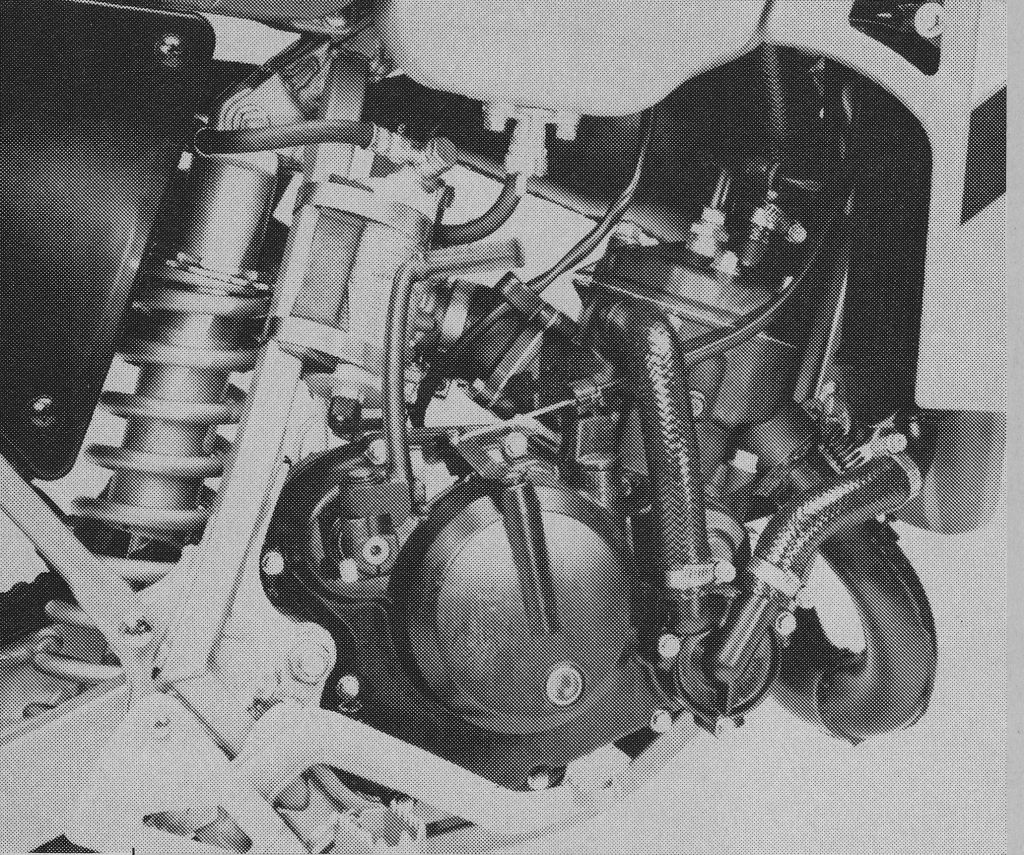

An all-new motor for 1986 repositioned the intake tract, reduced compression, and reconfigured the porting. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

An all-new motor for 1986 repositioned the intake tract, reduced compression, and reconfigured the porting. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Redesigned bodywork for ’86 offered larger side plates, a flatter seat, a slimmer tank, and increased roost protection from a larger rear fender. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

With the move away from the original Uni-Trak, Kawasaki had to dial up an all-new rear suspension system for 1986. Originally, Kawasaki, Suzuki, Honda, and Yamaha had all developed very different solutions for their single shock rear suspensions. Yamaha’s Mono-X, Honda’s Pro-Link, Suzuki’s Full Floater, and Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak all used some variation of a bell crank rising rate linkage in their designs, but all four were unique in their shock placement and linkage design. Of the original Japanese designs, Suzuki’s proved the most effective at taming the track, but it was also the largest and most complicated of the four. Both the original Full Floater and Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak placed the largest and heaviest components of the linkage up high and right in the spot that made packaging of other components difficult.

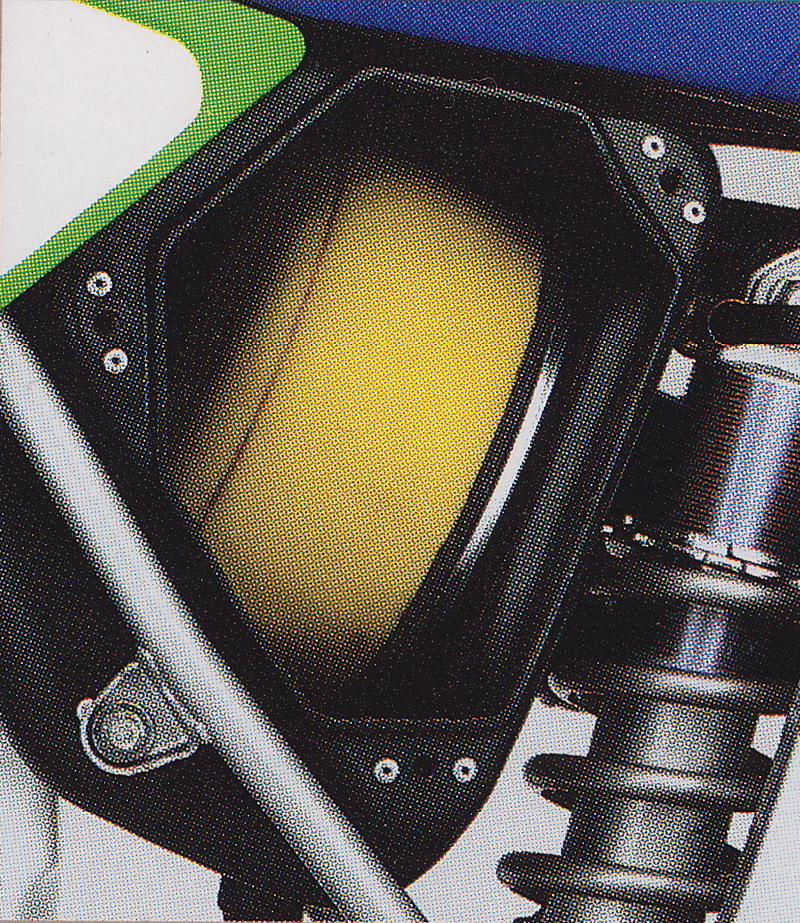

Repositioning the Uni-Trak hardware below the shock allowed Kawasaki’s engineers to increase the size of the airbox and straighten the intake tract for 1986. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Repositioning the Uni-Trak hardware below the shock allowed Kawasaki’s engineers to increase the size of the airbox and straighten the intake tract for 1986. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Of the original four designs, Honda’s Pro-Link proved to be the most effective at juggling performance, packaging, and weight distribution. By moving all the linkage components to the lower shock mount, Honda was able to keep their design light and compact while also keeping the heaviest bits low on the chassis to optimize handling. While the advantages of the Pro-Link were not immediately apparent on the track, it did not take the other manufacturers long to work out that Honda’s design offered the least number of compromises. In 1986, both Suzuki and Kawasaki retired their large and elaborate original monoshock designs in favor of Honda-style bottom link configurations on their minis.

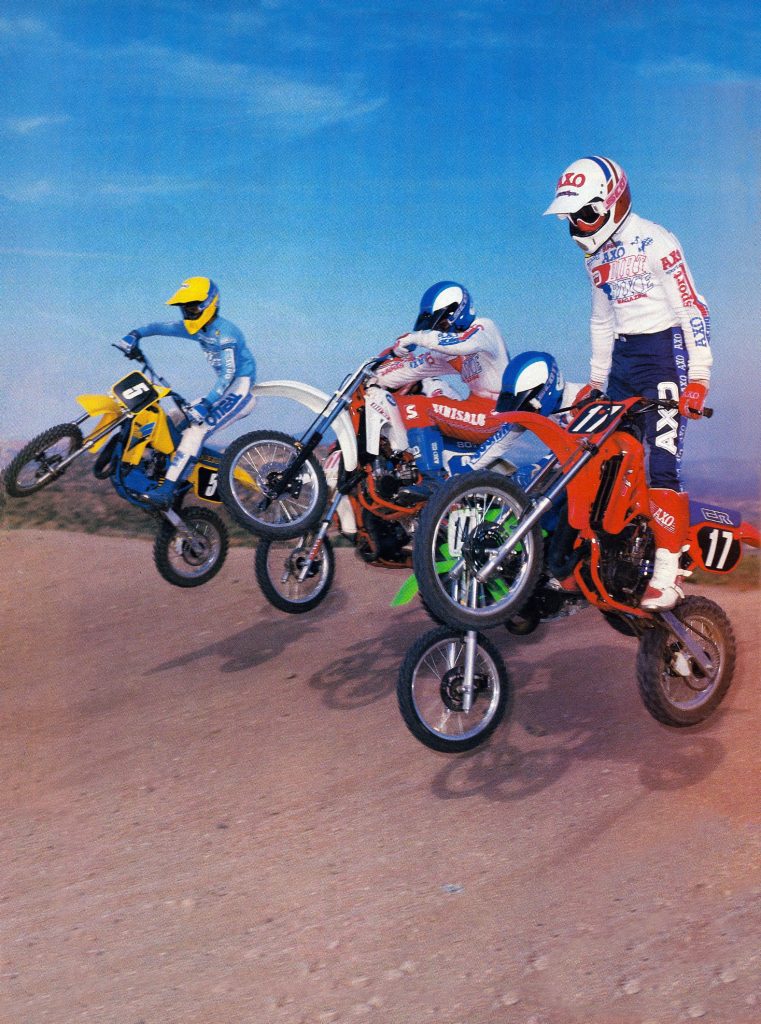

The mini class was the most hotly contested in motocross in 1986. All four of the Japanese minis were all-new with big changes across the board. Even the Austrians were invited to the party with all-new KTM 80MX, bringing a bit of Old-World charm for those tired of the ubiquitous Japanese. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The mini class was the most hotly contested in motocross in 1986. All four of the Japanese minis were all-new with big changes across the board. Even the Austrians were invited to the party with all-new KTM 80MX, bringing a bit of Old-World charm for those tired of the ubiquitous Japanese. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With the move to the new Uni-Trak, Kawasaki was able to enlarge the airbox, straighten the intake tract, and move a significant portion of the machine’s weight lower on the chassis. The new rear suspension was improved for 1986 with an all-new alloy swingarm, redesigned Uni-Trak linkage, and all-new Kayaba remote reservoir shock. The new damper was fully rebuildable (a real advantage at the time) with nearly 11 inches of rear wheel travel. In 1985, the KX80’s rear shock offered spring preload and adjustable rebound damping only. For 1986, Kawasaki brought the KX80’s damper in line with its bigger brothers by adding four adjustable settings for compression damping to go with its four selections for rebound control.

With slim ergos and a roomy riding compartment, the 1986 KX80 fit a wide variety of mini pilots. Photo Credit: Mike Gaspar

With slim ergos and a roomy riding compartment, the 1986 KX80 fit a wide variety of mini pilots. Photo Credit: Mike Gaspar

Up front, all-new forks from Kayaba improved handling feel by growing 2mm in diameter. With larger kids, faster motors, and increased suspension travel, it was becoming apparent that larger, less flexy forks were becoming a must in the hotly contested mini division. For 1986, Kawasaki moved to an all-new 35mm front fork that made them the beefiest silverware available in the ’86 Japanese mini division. In addition to being larger in diameter, the new KYB components increased travel to 10.8 inches, which was an increase of nearly an inch over 1985. As was the standard for the time, the new fork’s damping was locked at the factory and offered no external adjustments for compression or rebound damping.

None of the 80s were bad handlers in 1986, but of the five minis, none were as nimble in the turns as the revamped CR80R. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

None of the 80s were bad handlers in 1986, but of the five minis, none were as nimble in the turns as the revamped CR80R. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the motor front, the KX80 was just as all-new for 1986. The new motor repositioned the intake 10 degrees to offer a straighter shot from the carburetor and enlarged the airbox. The internal dimensions of the motor remained unchanged, with the pocket rocket featuring a 48mm x 48.5mm bore and stroke and 82cc of displacement. The redesigned top end lacked any sort of variable exhaust port trickery, but it did offer all-new porting, increased compression, and an enlarged reed valve that moved from two pedals to four for 1986. The ignition was updated to match the new porting, and a redesigned exhaust was bolted up to help the spent gases get out of the Hot Rod cylinder more efficiently. As in 1985, a 29mm “R-slide” Mikuni carburetor handled the mixing duties.

The revamped Uni-Trak delivered a firm but well-controlled ride in 1986. Big jumps and large whoops were no issue for the new bottom-link suspension. Larger and faster kids loved its performance, but smaller and less skilled pilots found its lack of low-speed compliance and comfort less appealing. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The revamped Uni-Trak delivered a firm but well-controlled ride in 1986. Big jumps and large whoops were no issue for the new bottom-link suspension. Larger and faster kids loved its performance, but smaller and less skilled pilots found its lack of low-speed compliance and comfort less appealing. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Additional motor improvements for 1986 included an updated water pump that moved to a gear-driven design. The new pump featured a smaller impeller with a revised shape to reduce internal pressure and prevent coolant from leaking past the pump shaft’s seal into the transmission. The new impeller also slowed down coolant flow slightly to allow for more efficient operation. The transmission was updated for ’86 with a lighter shift drum, and the motor’s primary drive was lowered slightly as well.

All-new forks for 1986 offered 2mm larger stanchions and nearly an inch of additional travel. While beefy and flex-free, their soft springs and light damping were out of step with the firmer settings found in the rear shock. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

All-new forks for 1986 offered 2mm larger stanchions and nearly an inch of additional travel. While beefy and flex-free, their soft springs and light damping were out of step with the firmer settings found in the rear shock. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the track, the revamped KX80 turned out to be a far more polarizing machine than the nearly unanimously praised ’85 machine had been. On the plus side was the KX’s all-new chassis that allowed fast kids to attack the track as never before. The beefy forks, stout frame, and revamped Uni-Trak allowed kids with speed to charge at 100% without fear of overriding the chassis. The forks were noticeably less flexy than the Japanese competition (KTM also used 35mm legs in 1986), and the KX never shook its head in the rough or swapped unexpectedly. The new layout was excellent, and riders could easily climb all over the machine to weight the front end or make a mid-flight correction. It was far roomier than in the past, with taller kids loving the new, larger rider compartment. Turning remained decent, but the KX was still not on par with shredders like Honda’s CR80R. It could get the job done in the turns and was the most stable machine in the class at speed.

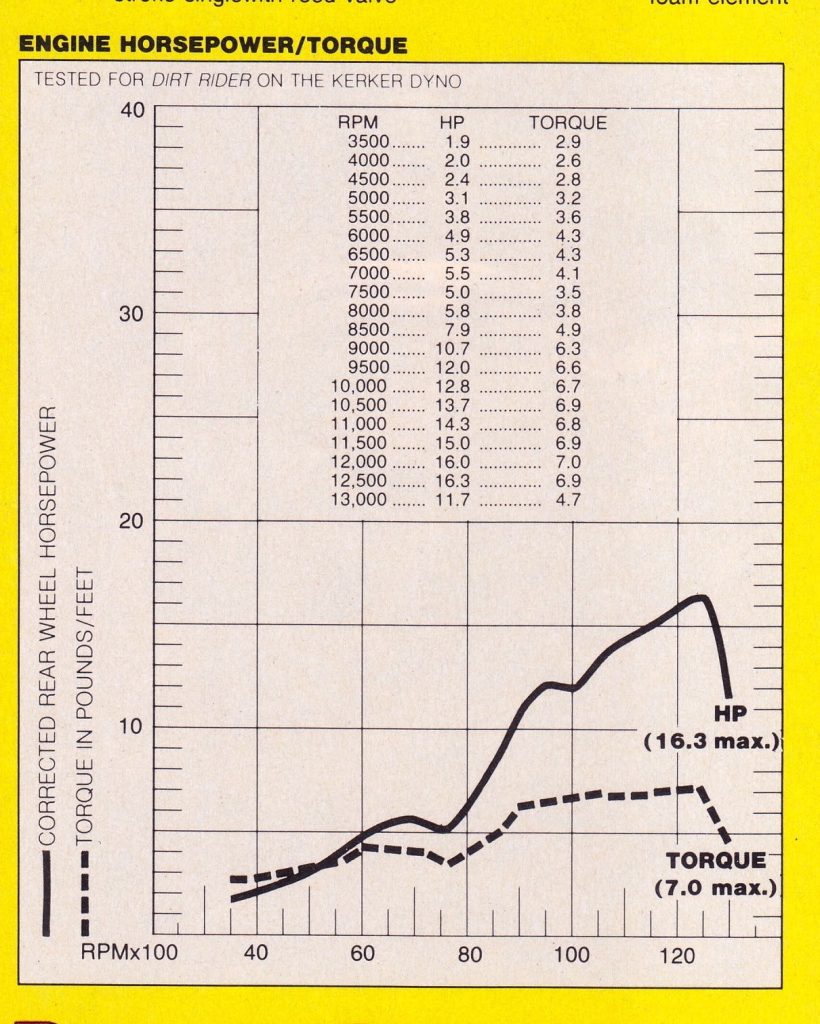

The KX80’s 16.3 max horsepower was in line with what the new Suzuki and Yamaha were pumping out, but all three power plants paled in comparison to the 18.3 ponies Honda’s CR80R was putting to the track in ’86. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The KX80’s 16.3 max horsepower was in line with what the new Suzuki and Yamaha were pumping out, but all three power plants paled in comparison to the 18.3 ponies Honda’s CR80R was putting to the track in ’86. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The new KX80 was an able jumper in 1986, but its soft fork settings made serious aerial work inadvisable until the front springs were upgraded. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The new KX80 was an able jumper in 1986, but its soft fork settings made serious aerial work inadvisable until the front springs were upgraded. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the suspension front, the KX80 was improved in 1986, but far from perfect. For most riders, the chief complaint was the mismatched settings of the new forks and shock. The new forks offered damping on par with the best in the class, but fast guys found the stock springs too soft for hard charging. They worked well on small chop but blew through their stroke on hard hits. In contrast, the new Uni-Trak rear suspension was set up very firmly. The rear’s action was excellent on hard hits but harsh on small chop. This hard rear, soft front combo messed with the KX’s balance and put even more stress on the soft front forks. Fast kids liked the firm shock but complained about the marshmallow forks, while less experienced racers had no qualms with the forks but complained about the kidney-busting shock. Neither end of the spectrum was particularly happy with the stock settings, and both were likely to need some assistance from the aftermarket to balance things out.

The KX’s all-new 82cc mill ran completely different from the year before. The chunky low-to-mid delivery of ’85 was replaced with a high-RPM powerband that lacked the torque and response of the previous mill. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The KX’s all-new 82cc mill ran completely different from the year before. The chunky low-to-mid delivery of ’85 was replaced with a high-RPM powerband that lacked the torque and response of the previous mill. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

While the chassis turned out to be a bit of a mixed bag in 1986, it was nothing compared to the controversy that arose from the KX’s all-new powerband. From 1982 through 1985, the KX80 had dominated mini class racing by offering the beefiest and broadest power in the mini division. Kawasaki’s mini missile felt like a 105 compared to the high-strung 80cc competition, and that powered it to countless victories in the magazines and on the track. For 1986, Kawasaki moved all that power from the basement to the tenth floor, and not everyone was on board with the move to the powerband penthouse. Where the old motor barked out of the hole and ripped into the midrange, this new version was listless down low, requiring a strong dose of clutch to get the motor into the powerband. Low-to-mid power was nearly nonexistent, with all its power now placed at the upper reaches of the rev band. Once it was on the pipe, the KX was wicked fast, but that power was hard to find and even harder to keep. It required lots of clutch, skill, and commitment to keep the high-strung powerband percolating, and even mini experts thought the old motor was far superior.

There were a lot of solid choices in the 1986 mini class, but for most racers, the Honda CR80R was the pick of the litter. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

There were a lot of solid choices in the 1986 mini class, but for most racers, the Honda CR80R was the pick of the litter. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

For riders of lesser skill and experience, the new motor proved highly frustrating. It lacked torque out of turns and easily fell off the pipe between gears if not pinned to the stops. Riders coming off ’85 and older KX80s were shocked at the sudden lack of low-to-mid power and quite disappointed with the power characteristics of the new machine. Every machine in the class offered an easier-to-ride power package in ‘86, and the KX plummeted from the top of the powerband sweepstakes to the bottom of the heap. Really fast kids could make its high-RPM powerband work, but even they felt the motor needed a bit more midrange to fall back on. For expert-level racing it was a competitive motor, but for the other 95% of mini racers, it was a tremendous step backward in 1986.

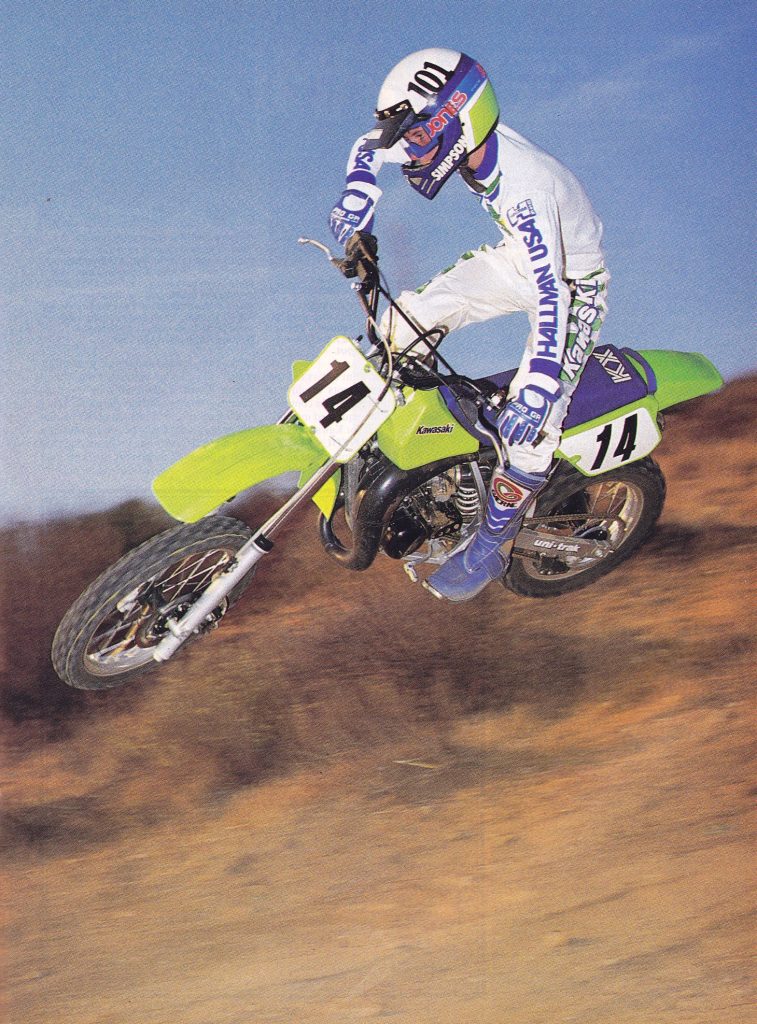

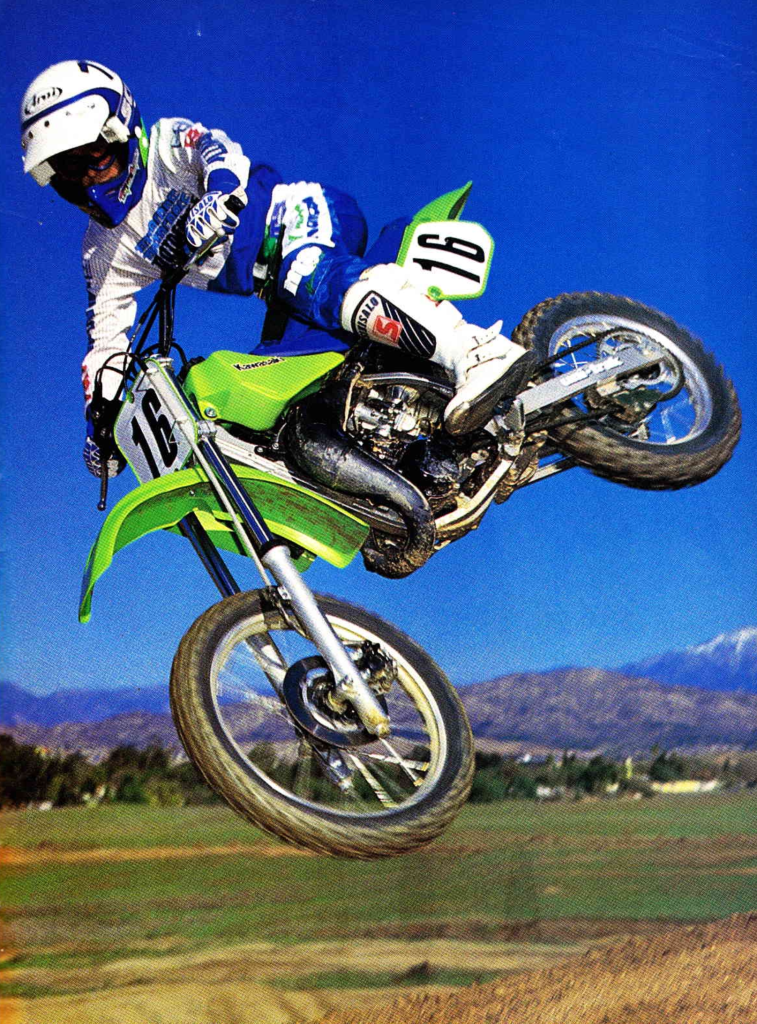

Talented riders like Terry Swanson could do some amazing things on the KX80 in 1986. Photo Credit: Mike Gaspar

Talented riders like Terry Swanson could do some amazing things on the KX80 in 1986. Photo Credit: Mike Gaspar

On the detailing front, the all-new KX80 was quite well finished for its time. The trick, fully removable rear subframe made servicing the shock much easier, with only Honda sharing this feature in 1986. The front disc was epically powerful, and the rear drum stopped the lightweight KX with ease. Riders praised the flat and comfortable riding position and slim midsection. The new seat and new tank made it easy to get forward in turns, and the overall rider triangle was a great fit for larger kids. Smaller riders were a better fit on the new Yamaha YZ80, but if you were hitting your growth spurt, the KX was a good fit in ’86.

The KX’s revamped motor was a bit of a disappointment to many in 1986, but the all-new layout and chassis were roundly praised for roominess, comfort, and confidence on the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The KX’s revamped motor was a bit of a disappointment to many in 1986, but the all-new layout and chassis were roundly praised for roominess, comfort, and confidence on the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The motor’s powerband was peaky, but it did shift smoothly, and the clutch generally worked well if not abused. The motor was also reliable as long as you ran good oil, kept the filter clean, and serviced the tiny top end at regular intervals. The quality of the plastic and fasteners was relatively poor, however, and it was easy to strip screws and nuts if you got a bit too aggressive with a wrench or screwdriver. The bars, chain, and sprockets were also pot metal, but this was par for the course in the mini class at the time. An upgrade to aftermarket alternatives was advisable if you planned on racing and putting much time on your KX.

Sometimes big gambles pay off, but in 1986, Kawasaki’s big bet crapped out in a very competitive mini division. The all-new KX80 doubled down on pro-focused performance, but ended up turning off the fan base that had made it such a tremendous hit the previous four seasons.

Sometimes big gambles pay off, but in 1986, Kawasaki’s big bet crapped out in a very competitive mini division. The all-new KX80 doubled down on pro-focused performance, but ended up turning off the fan base that had made it such a tremendous hit the previous four seasons.

In the end, the 1986 KX80 turned out to be an upgrade in some ways and a significant step backwards in others. The updated chassis improved handling, and the longer travel suspension allowed fast kids to push harder than ever, but that performance came at a cost. The revamped motor was plenty fast, but its power was much harder to access than in the past. The brawny motor that propelled the KX80 to the top of the mini division was MIA for 1986, and that hurt its appeal for the majority of prospective mini-class buyers. With some motor mods and a bit of suspension fine-tuning the KX could be a winner, but that decision was no longer the no-brainer it had been the previous four seasons. If you had the skill and bravado to keep its high-RPM motor singing, then the Kawasaki was a solid pick, but if your talents ran more to the mean, then the Honda and Suzuki were much better choices in 1986.