For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Yamaha’s YZ250 for 1989.

In 1989, Yamaha’s YZ250 looked very much like a warmed-over version of the ’88 machine, but that familiar appearance hid a surprising list of upgrades. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1989, Yamaha’s YZ250 looked very much like a warmed-over version of the ’88 machine, but that familiar appearance hid a surprising list of upgrades. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1988, Yamaha introduced an all-new YZ250 to rave reviews. Reimagined from the ground up, the new Yamaha deuce-and-a-half offered significant improvements in nearly every performance category. Major upgrades in suspension, ergonomics, and handling transformed the YZ from an also-ran to one of the top dogs in the 250 division. Riders loved the YZ’s YZM-inspired styling, the machine’s strong low-end power, and its well-sorted suspension. It was not the best bike in any one category, but it was a well-rounded package that offered an attractive alternative to Honda’s sexy but flawed all-new CR250R.

All-new in 1988, Yamaha’s YZ250 made a splash winning Motocross Action’s 250 motocross shootout and quite a few admirers with its works-like asymmetrical shrouds and sexy styling. Photo Credit: Yamaha

All-new in 1988, Yamaha’s YZ250 made a splash winning Motocross Action’s 250 motocross shootout and quite a few admirers with its works-like asymmetrical shrouds and sexy styling. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1989, the YZ250 was back with a surprising number of updates for such a successful machine. Despite excellent sales figures and a victory in Motocross Action’s 1988 250 Motocross shootout, Yamaha chose to scrap 90% of the ’88 YZ’s design in favor of another all-new platform. About the only thing that was not changed for 1989 was the works replica bodywork, which returned with a minor update to the graphics. This meant that the two machines appeared very similar at first glance, but underneath the old bodywork beat the heart of an all-new machine.

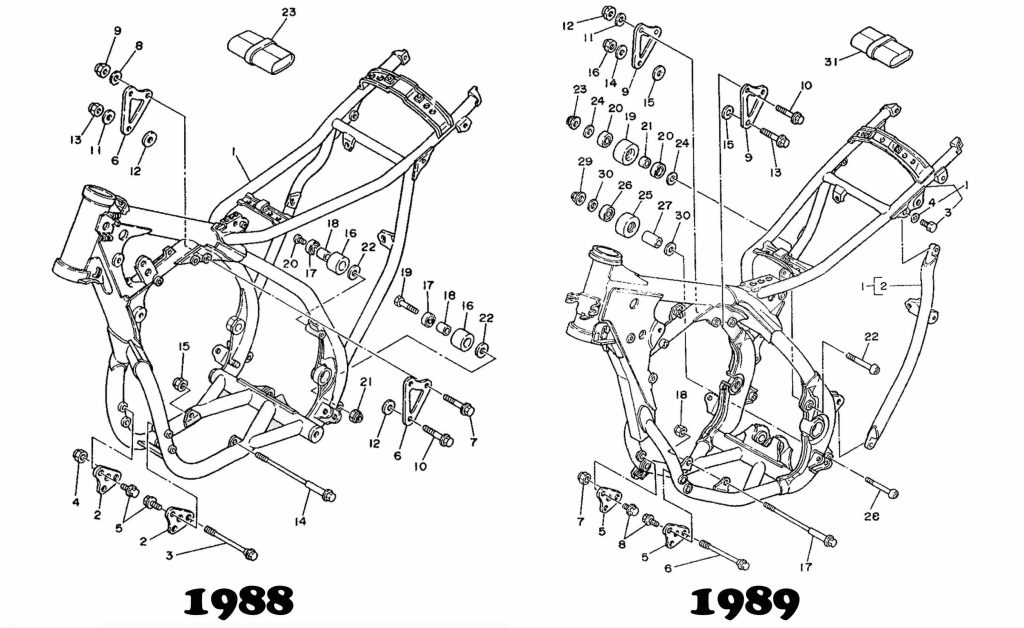

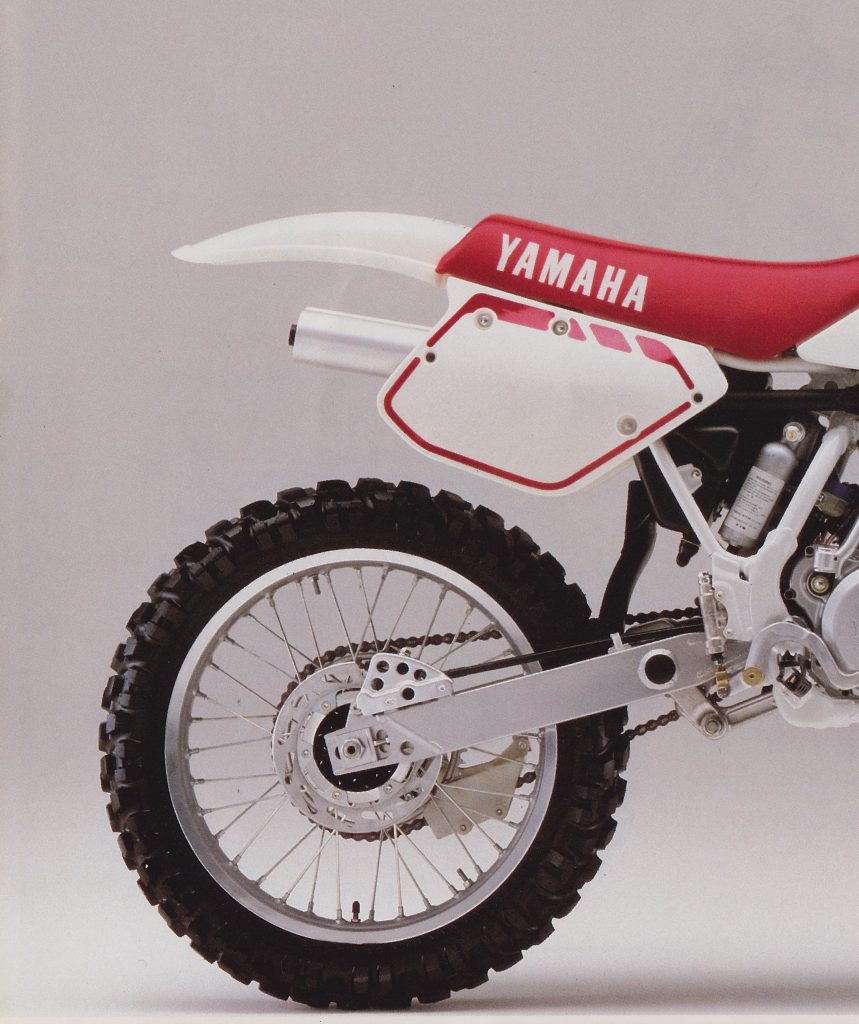

An all-new frame for 1989 upped the strength of the YZ chassis considerably by enlarging the tubing, adding substantial gusseting and boxing in the swingarm pivot. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new frame for 1989 upped the strength of the YZ chassis considerably by enlarging the tubing, adding substantial gusseting and boxing in the swingarm pivot. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Visually, the biggest change for 1989 was the switch from the ’88 model’s 43mm conventional forks to a set of all-new 41mm inverted Kayaba units. In use by the factory teams for several seasons, the inverted design offered several advantages over its conventional counterparts. Moving the larger portion of the forks to the clamping area increased the rigidity of the front end considerably and reduced the unsprung weight of the forks. It also reduced the protrusion of the forks below the axle, thus lessening the chance of catching the forks in a rut. With Supercross becoming an ever-greater focus of the manufacturers, it was felt that the inverted fork’s increased rigidity outweighed any offsetting reduction in compliance the switch would result in.

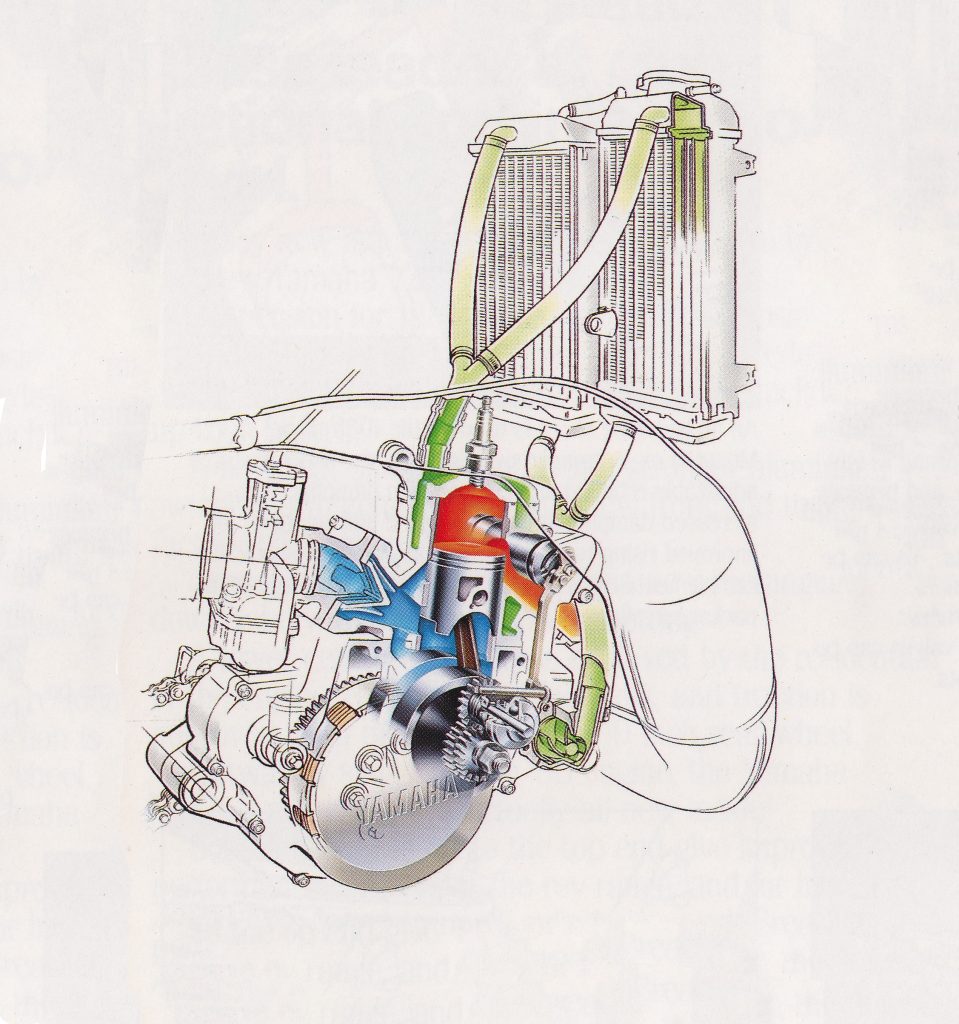

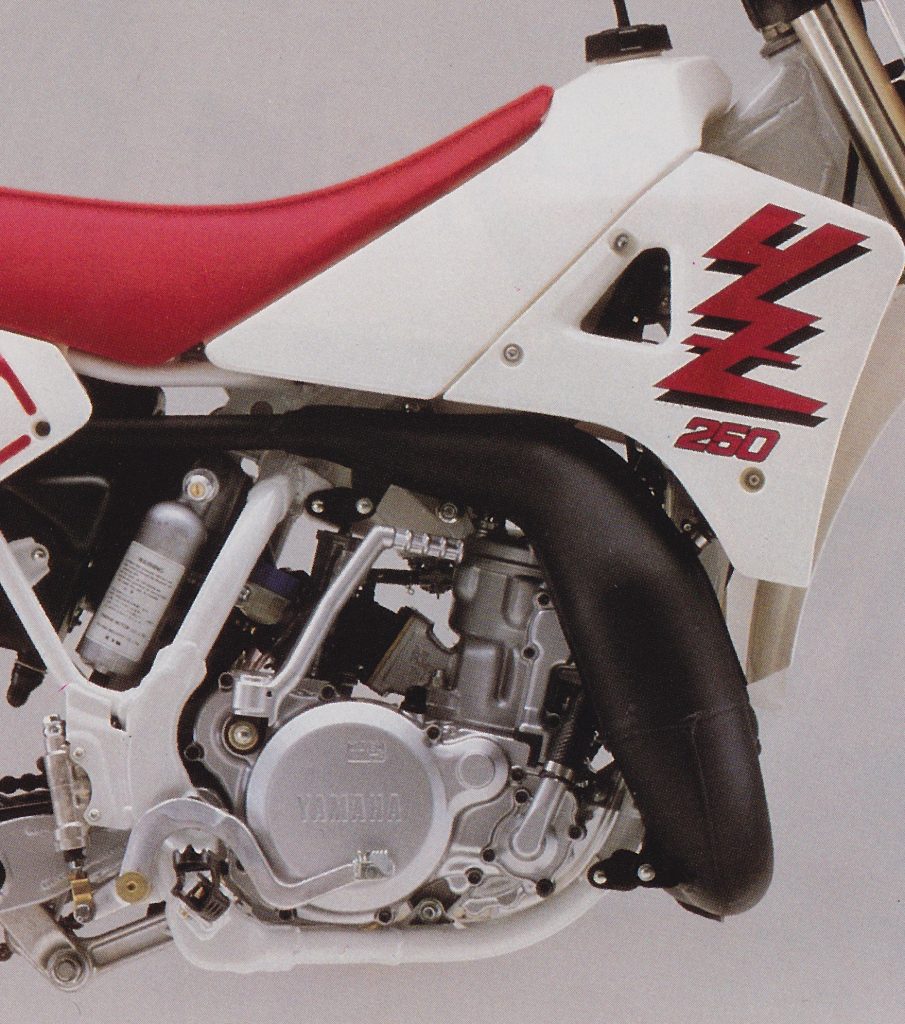

While the basic DNA of the YZ250’s motor stretched back to 1982, a steady diet of upgrades kept it competitive with its newer rivals. For 1989, a revamped cylinder, new carburetor, and revised intake highlighted the changes for Yamaha’s venerable YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) mill. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While the basic DNA of the YZ250’s motor stretched back to 1982, a steady diet of upgrades kept it competitive with its newer rivals. For 1989, a revamped cylinder, new carburetor, and revised intake highlighted the changes for Yamaha’s venerable YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) mill. Photo Credit: Yamaha

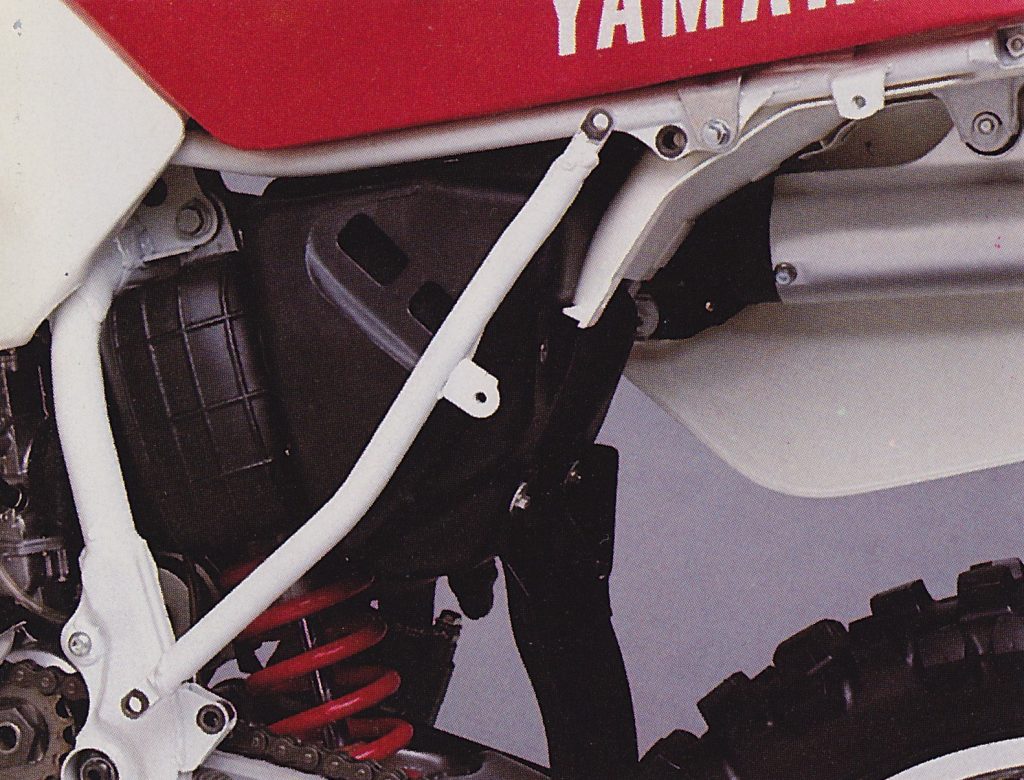

With the move to inverted forks, the old YZ’s frame was no longer sufficiently strong enough to handle the increased loads presented by the more rigid front end. As a result, Yamaha’s engineers spec’d an all-new chassis design for 1989. The new frame beefed up the steering head substantially with increased bracing and a new box-section front downtube. Both the engine cradle and main frame spars were increased in diameter and the swingarm pivot was fully boxed in for the first time. In addition to the increased strength, the new frame altered the YZ geometry slightly by increasing the trail by one millimeter and reducing the rake by one degree. Both radiators were repositioned lower on the frame to help centralize mass and the footpegs were moved rearward slightly to improve ergonomics. Another welcome addition for ‘89 was the incorporation of a removable bar into the rear section of the frame. While not as convenient as the fully removable subframes found on the KX and CR, this new addition made servicing the shock significantly easier.

Another significant upgrade for 1989 was the addition of a removeable bar on the rear of the frame to make shock and airbox access easier. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Another significant upgrade for 1989 was the addition of a removeable bar on the rear of the frame to make shock and airbox access easier. Photo Credit: Yamaha

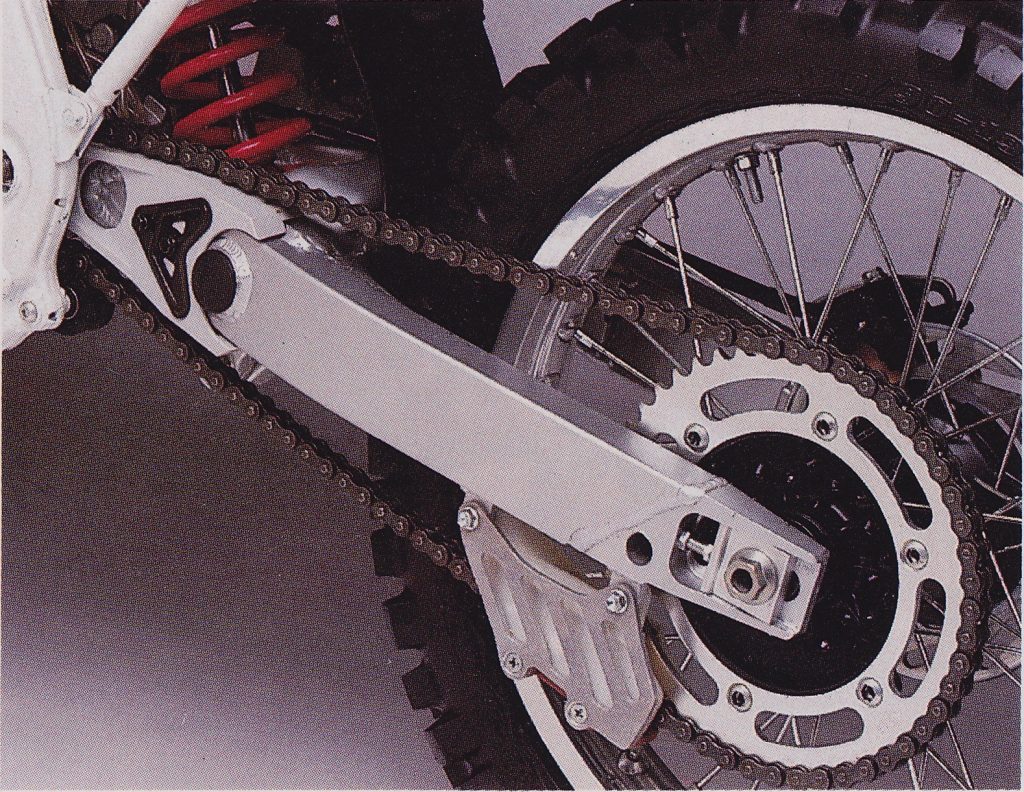

Paired with the new frame were an all-new swingarm and redesigned shock. The shock remained a Kayaba unit but a new “bladder type” design promised improved damping and increased fade resistance. The new swingarm was substantially larger and stronger for 1989 with a move to “push-style” chain adjusters for improved reliability. In addition to the improved chain adjusters for 1989, the YZ also adopted a new chain buffer that offered a softer compound to alleviate the annoying chain clatter of the previous three years. New chain rollers for 1989 offered longer life and reduced noise and a redesigned chain guide added aluminum bracing for improved durability. All-new brakes for 1989 offered larger slots for improved cooling and increased pad life. Both the front and rear calipers were redesigned for improved performance and easier maintenance. In the rear, a sano “works style” caliper guard improved the appearance of the YZ by replacing the oversized and cobby guard of 1988 with a lighter and much more finished design straight off of Micky Dymond’s factory racer.

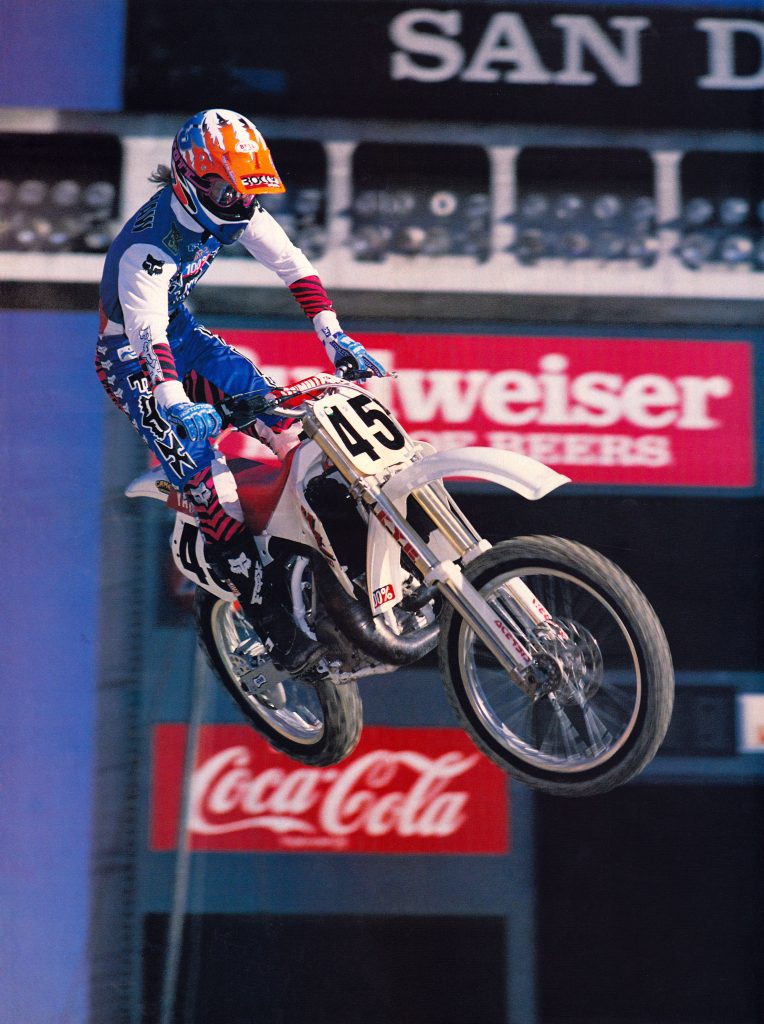

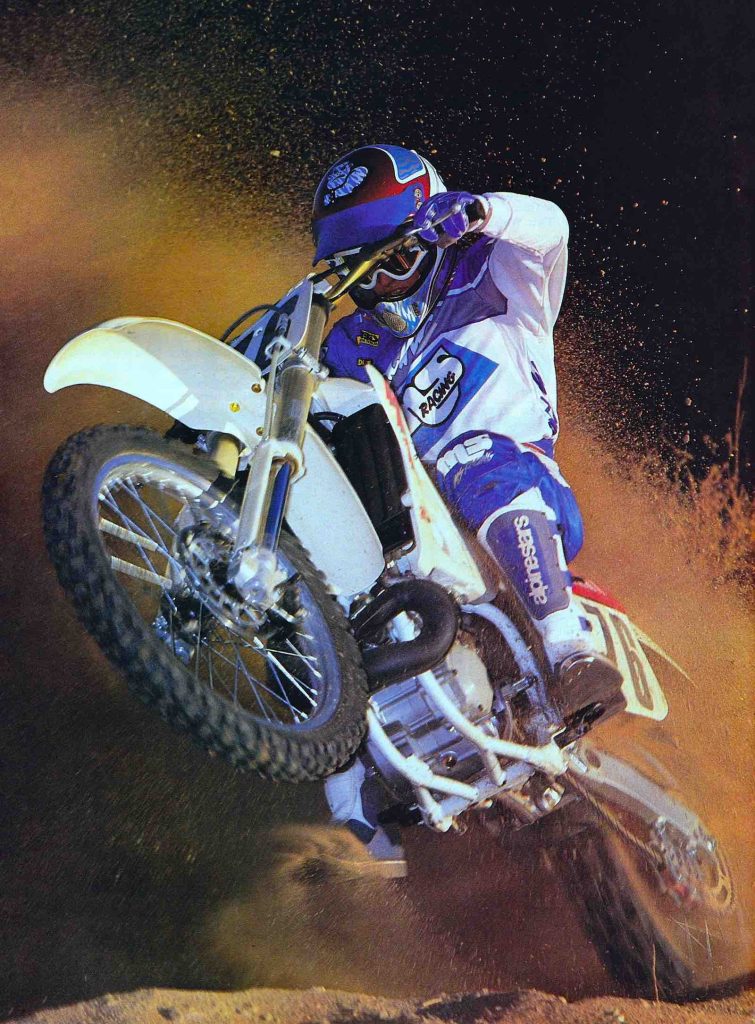

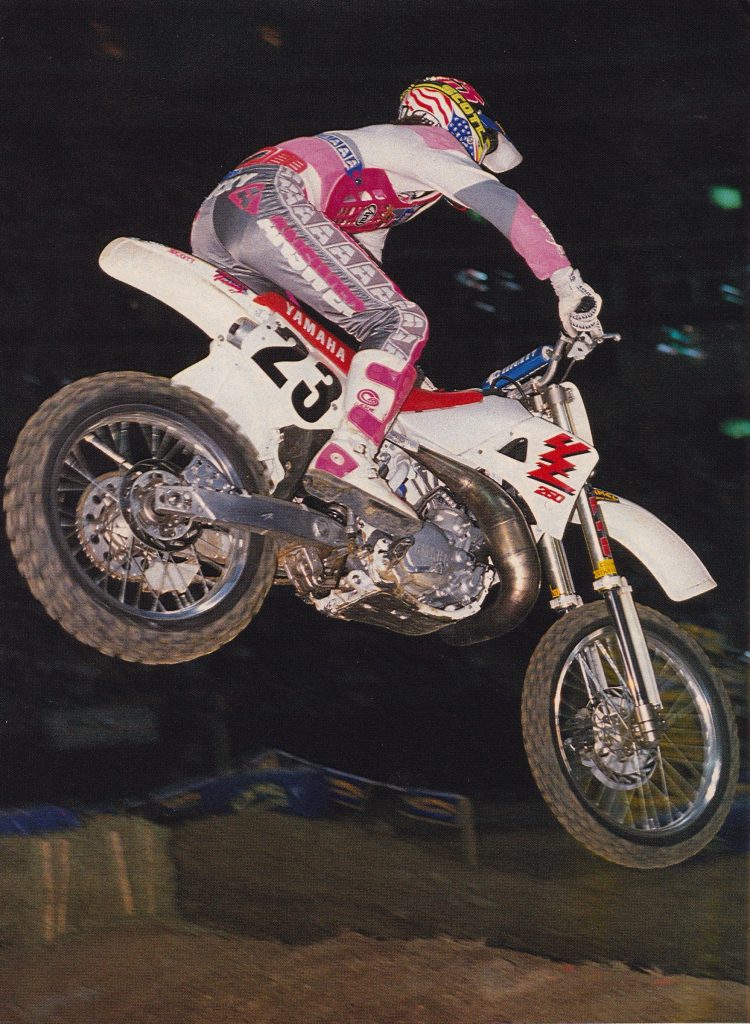

Coming into the 1989 season, rookie Damon Bradshaw was Yamaha’s biggest star despite his not yet winning a professional AMA event. Bradshaw’s incredible raw talent and a win over Rick Johnson at Osaka in 1988 served as notice that the kid was ready to do big things once he moved up to the YZ250 full time. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

Coming into the 1989 season, rookie Damon Bradshaw was Yamaha’s biggest star despite his not yet winning a professional AMA event. Bradshaw’s incredible raw talent and a win over Rick Johnson at Osaka in 1988 served as notice that the kid was ready to do big things once he moved up to the YZ250 full time. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

Aside from the forks, the most significant change made to the YZ’s chassis in 1989 was the move to a 19” wheel in the rear. This was also a trick pioneered by the factory teams as they searched for ways to extract more traction out of the hard and slippery Supercross circuits. As with the forks, the move to a 19” rear wheel was a game of trade-offs as both the 18” and 19” wheels offered their own set of advantages and weaknesses. For professional racing, the 19” made a lot of sense as its shorter and stiffer sidewalls offered less flex in the turns and better feel under acceleration. The trade-off for this was less flat protection, less tire selection (at the time), and a slightly firmer ride in the rough. For motocross, this seemed like a fair trade-off but riders looking for a do-it-all machine might have been happier switching back to an 18” hoop. In 1989, this debate was far from settled and Honda would continue to equip its CR models with an 18” rear wheel well into the next decade.

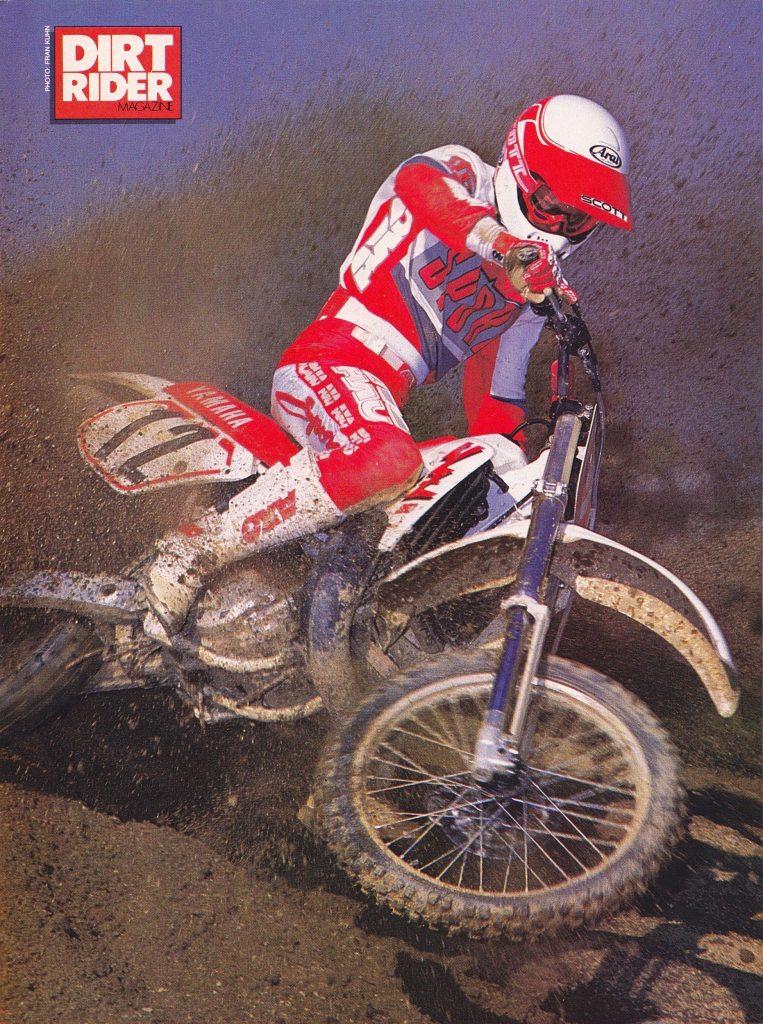

Topsy-turvy: In 1989, Yamaha joined Honda and Suzuki in making the jump to inverted forks on their 250 machines. KTM had made the move back in 1985 but the Japanese were slower to make the change. Here in the US, Kawasaki decided to stick with a conventional design for one more year but international KXs adopted an inverted design in 1989 as well. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Topsy-turvy: In 1989, Yamaha joined Honda and Suzuki in making the jump to inverted forks on their 250 machines. KTM had made the move back in 1985 but the Japanese were slower to make the change. Here in the US, Kawasaki decided to stick with a conventional design for one more year but international KXs adopted an inverted design in 1989 as well. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

While most of the YZ’s bodywork was a carryover from 1988, there were some minor changes made to the layout for 1989. A new bar (still steel) offered a revised “Micky Dymond” bend for an improved feel and a new seat was added with additional foam in the midsection to provide a flatter riding compartment. The new frame also lowered the rear of the machine slightly to aid rider movement. A redesigned airbox necessitated a new left-side number plate as the access moved from the side to under the seat for 1989. The tank and works-style asymmetrical shrouds were carryovers from the year before but bold new “YZ” graphics gave the machine a fresh look for 1989.

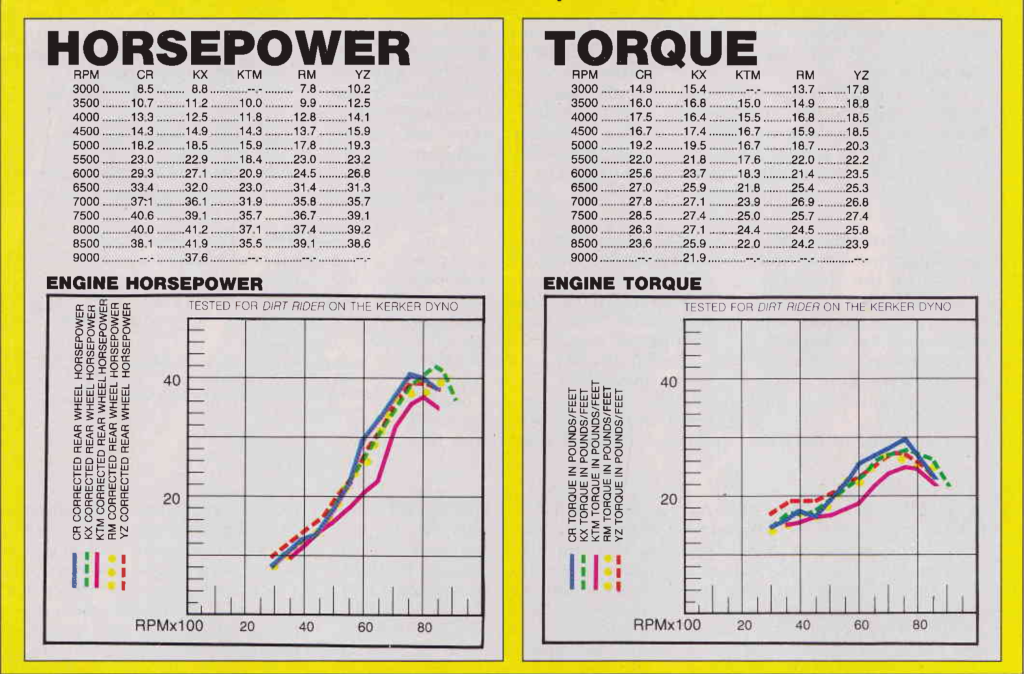

While the YZ250 did pick up 2.8 horsepower for 1989, it still lagged well behind class powerhouses like the Kawasaki KX250 and Honda CR250R. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

While the YZ250 did pick up 2.8 horsepower for 1989, it still lagged well behind class powerhouses like the Kawasaki KX250 and Honda CR250R. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

In 1988, the YZ250 had offered an abrupt and instant style of power that launched the bike out of turns at the slightest hint of throttle. It was quicker than it was fast but very fun to ride and extremely effective. In 1989, Yamaha’s engineers looked to build on the ‘88 machine’s success by broadening and boosting the power of their 250 racer.

Despite being outmuscled on the dyno, the YZ’s power plant was very competitive in 1989. Its blend of “right now” response and a chunky midrange blast made it very quick and fun to ride. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

Despite being outmuscled on the dyno, the YZ’s power plant was very competitive in 1989. Its blend of “right now” response and a chunky midrange blast made it very quick and fun to ride. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

To accomplish this the engineers spec’d an all-new cylinder for 1989. The new jug featured revised porting and a massaged power valve. The YPVS timing was altered to open 250 rpm later and the compression was increased slightly through the use of plugs in the crank. A new reed valve was installed that reduced the count from eight pedals to six for increased intake velocity and an all-new pipe and silencer were bolted on that were designed to reduce sound, improve ground clearance, and increase top-end power. The new pipe also tucked in better to reduce the chance of burning the rider’s leg and lowered vibration by adding an additional mounting point to the frame.

An all-new swingarm, beefed-up chain guide, and revised chain buffer were all welcome changes on the YZ250 in 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new swingarm, beefed-up chain guide, and revised chain buffer were all welcome changes on the YZ250 in 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Further refining power for 1989 was an all-new airbox that offered improved breathing and a three-fold increase in airboot volume. The carburetor was all-new as well with a move from the 38mm round-slide of 1988 to the all-new flat-slide Mikuni TM38SS. Mikuni claimed this 38mm carb offered improved throttle response and bottom-end torque due to the improved fuel atomization offered by the flat-slide design. The clutch and transmission remained unchanged for 1989 with the YZ offering a close-ratio five-speed to put the power to the ground.

The YZ’s motor changes for 1989 added up to a smoother and slightly broader delivery than in 1988. There was still not much pull on top, but the 246cc motor’s instant throttle response and strong low-to-mid power kept it in the running as long as the track was not too wide open. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The YZ’s motor changes for 1989 added up to a smoother and slightly broader delivery than in 1988. There was still not much pull on top, but the 246cc motor’s instant throttle response and strong low-to-mid power kept it in the running as long as the track was not too wide open. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the track, the new YZ250 turned out to be an improved version of the bike riders had enjoyed the year before. The new chassis, revamped suspension, and massaged motor delivered a sharper, snappier, and even more serious machine for 1989. The new motor pumped out 2.8 more horsepower than the ‘88 and delivered that performance over a broader effective range. It was slightly less abrupt down low and easier to get hooked up than in 1988 but no less strong. The burst of the old motor was smoothed out and funneled into a stronger midrange hit that continued pulling slightly farther than before. The motor felt more responsive to throttle input and seemed to rev slightly quicker as well. There was still not a lot of pull on top but the new YZ could be left on longer without fear of the bike falling off the pipe.

In 1988, Micky Dymond signed on to Team Yamaha with a fair amount of hype as a two-time AMA 125 National Motocross Champion. Two years later, he was let go after disappointing results, injuries, and a perceived lack of commitment soured the Yamaha camp on his talents. Two podiums and a second-place at East Rutherford in 1989 would be the lone highlights of his two-year stint with the brand. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1988, Micky Dymond signed on to Team Yamaha with a fair amount of hype as a two-time AMA 125 National Motocross Champion. Two years later, he was let go after disappointing results, injuries, and a perceived lack of commitment soured the Yamaha camp on his talents. Two podiums and a second-place at East Rutherford in 1989 would be the lone highlights of his two-year stint with the brand. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Chassis upgrades for 1989 added up to a much more accurate handling package on the YZ250. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

Chassis upgrades for 1989 added up to a much more accurate handling package on the YZ250. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

Compared to its 250 rivals the YZ was competitive but not class-leading. Both the ’89 CR and KX offered significantly more top-end power and the RM delivered a stronger midrange burst. The Yamaha, however, was easier to ride than all three and offered an always-ready style of power that hooked up and hauled at a moment’s notice. The YZ was very quick from corner to corner and great for clearing tricky doubles right out of turns. Its transmission was still slightly notchy but the revised footpeg placement for 1989 seemed to deliver more leverage and a slight reduction in the old grumpiness to catch the next gear. Overall, it was a great motor that got the job done with flexibility and power placement rather than gaudy dyno numbers.

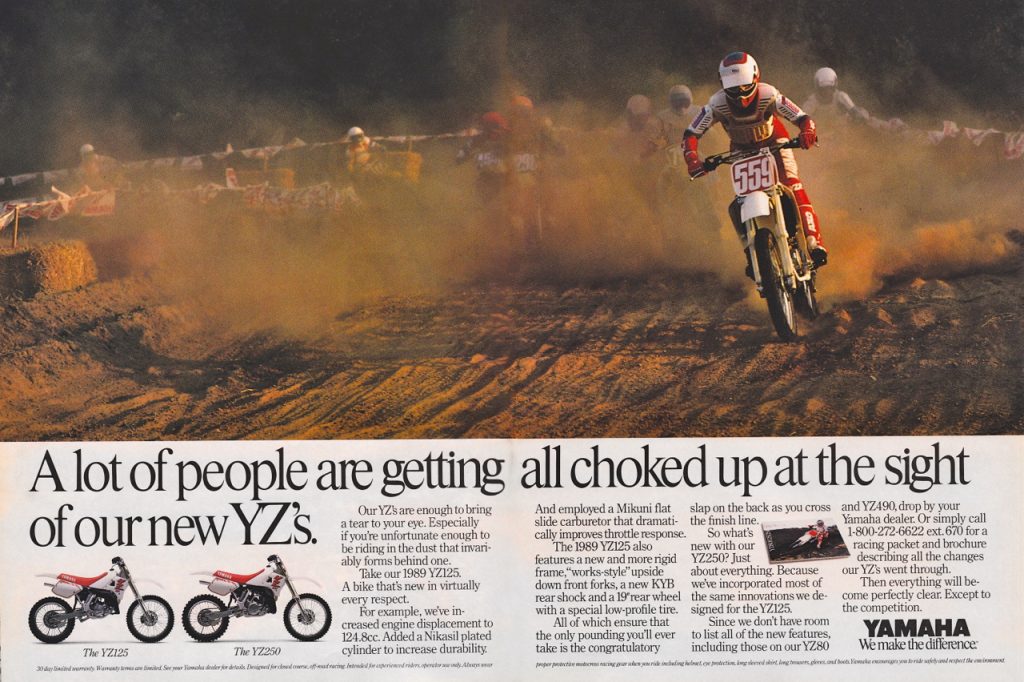

A fairly unknown rider from La Porte, Indiana by the name of Mike LaRocco starred in Yamaha’s ad for the new YZs in 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

A fairly unknown rider from La Porte, Indiana by the name of Mike LaRocco starred in Yamaha’s ad for the new YZs in 1989. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the chassis front, the YZ250 was once again a solid improvement over 1988. The new frame and forks delivered a tremendous increase in chassis strength that could be felt on the track. There was far less flex in the rough and the front end felt far more sensitive to rider input. The new 41mm forks were not as stiff as the massive 45mm units found on the Honda and the Yamaha did a much better job of increasing feedback without sacrificing comfort. The new geometry and flex-free chassis improved the steering feel but the YZ remained less aggressive in the corners than its rivals. The Yamaha turned well, but its front-end traction was never quite as good as the fly-paper-like Honda and Suzuki. Thankfully, it also lacked the come-to-Jesus level of headshake inherent in the red and yellow machines. On the ground and in the air the YZ felt lighter than its 226 pounds and the machine could be thrown around nearly as easily as the feathery-feeling new RM250. The arrival of the 19” rear wheel was mostly unnoticed by testers who were evenly split on its merits. Most non-pros were unable to feel much of an improvement in rear-wheel traction, but several magazines noted an uptick in flats due to the reduction in the sidewall.

While not as flashy as some of its competition, the revamped YZ250 was more than capable of running with its rivals in 1989. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While not as flashy as some of its competition, the revamped YZ250 was more than capable of running with its rivals in 1989. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the end, the YZ’s best handling trait was its flexibility. It was equally as comfortable off-road as it was on the track. This made it more versatile than machines like the CR and RM but cost it somewhat if stadium-style handling was your number one priority. For hardcore motocross, it was not the most accurate machine available but if you intended to do more than just hit the track it was a very attractive handling package.

Yamaha’s new 41mm inverted KYB forks were able to avoid most of the teething problems that plagued Showa’s 45mm Honda offerings in 1989. While not as plush as the 46mm conventional forks found on the KX250, they offered a reasonably compliant ride that most riders felt was good enough to be raceable in stock condition. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Yamaha’s new 41mm inverted KYB forks were able to avoid most of the teething problems that plagued Showa’s 45mm Honda offerings in 1989. While not as plush as the 46mm conventional forks found on the KX250, they offered a reasonably compliant ride that most riders felt was good enough to be raceable in stock condition. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the suspension front, the new YZ was improved but not dramatically so. The new 41mm inverted Kayaba cartridge forks offered 12 inches of travel and 23 adjustments for compression damping but no external adjustments for rebound control. On the track, the new forks were solid if not spectacular performers. With their reduced size, they avoided most of the harshness complaints that plagued Honda’s new 45mm forks, but they still lacked the comfort and compliance of the Kawasaki’s excellent 46mm conventional units. They were decently plush over small obstacles and an improvement over 1988 but tended to bottom out harshly until the oil level was raised. They were certainly raceable in stock trim for most riders, but heavier or faster riders were likely to want stiffer springs and a revalve to get the most out of their performance.

The new KYB shock and revised rear suspension on the YZ offered a well-controlled ride that most riders praised for its performance. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The new KYB shock and revised rear suspension on the YZ offered a well-controlled ride that most riders praised for its performance. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Out back, the new Kayaba damper faired a bit better. The new swingarm was flex-free and the shock elicited praise for its smooth and well-controlled action. Big hits and small were taken in stride and the rear never reacted strangely or kicked suddenly. Pros and novices praised its action and the YZ was well suited for most riders out of the crate. Once again, the Kawasaki KX250 was credited with the best suspension action in the class but the YZ was a close second.

The YZ’s new graphics and works-style plastic looked great when new but did not hold up particularly well to long-term abuse. Photo Credit: East Coast Vintage

The YZ’s new graphics and works-style plastic looked great when new but did not hold up particularly well to long-term abuse. Photo Credit: East Coast Vintage

On the detailing side of things, the ‘89 YZ was a substantial improvement in some areas and a bit of a disappointment in others. Plastic fitment and quality continued to be rather lackluster and the YZ became notorious for pulling its radiator shrouds loose from their mountings. The stock decals were also of sub-par quality and not up to the demands of off-road abuse. If you did not cover them with 100%’s clear Force Fields they were not likely to outlast the first pressure washing.

Aside from the inverted forks, the other large shift in the motocross industry in 1989 was the move to 19” rear wheels. This larger hoop promised improved cornering and traction by reducing sidewall flex under heavy loads. While many were skeptical of this change initially, the 19” wheel has withstood the test of time. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Aside from the inverted forks, the other large shift in the motocross industry in 1989 was the move to 19” rear wheels. This larger hoop promised improved cornering and traction by reducing sidewall flex under heavy loads. While many were skeptical of this change initially, the 19” wheel has withstood the test of time. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Bolt quality and selection were much improved for 1989 with many of the annoying Phillips screws being retired in favor of much more practical 8mm and 10mm alternatives. Actual bolt quality was still not up to Honda standards but the YZ’s hardware easily outpaced the pot metal found on the KX and RM. No one much cared for the butter-soft Micky Dymond bend handlebars, rock-hard stock grips, and brittle levers, but the new rubber-mounted bar clamps were a welcome improvement. Both the front and rear brakes offered an improved feel for 1989, but neither end enjoyed the impressive power of the Honda and Kawasaki’s binders. Chain and sprocket life were poor, but the redesigned chain buffer and rollers wore well and were much quieter than the old clackity-clackers. The new inverted forks required guards to protect the lower sliders and Yamaha’s version leaned heavily on the minimalist approach used by the factory teams. While this looked trick, they offered far less protection than the wrap-around guards employed by Honda and were flimsy and easily damaged. MXA even suffered a spectacular crash when one of the fork guards on their test unit made its way out of its guide and into the spokes. Ouch.

Yamaha’s first version of a guard for their inverted forks closely resembled the designs used by the works teams but proved more fragile and less protective than the wrap-around units found on Honda’s CRs. Photo Credit: East Coast Vintage

Yamaha’s first version of a guard for their inverted forks closely resembled the designs used by the works teams but proved more fragile and less protective than the wrap-around units found on Honda’s CRs. Photo Credit: East Coast Vintage

In terms of overall reliability, however, the YZ was quite good in 1989. The bike tended to feel a bit looser and more worn out than its competition but it rarely broke. The motor was bulletproof, and the suspension was much less labor-intensive than the Kawasaki and Honda which demanded constant fluid changes to maintain their performance. The lack of a removable clutch cover and tiny oil fill hole made some maintenance a chore, but the Yamaha’s YPVS top end was much less infuriating to work on than the Honda’s Rube Goldberg-esque HPP system.

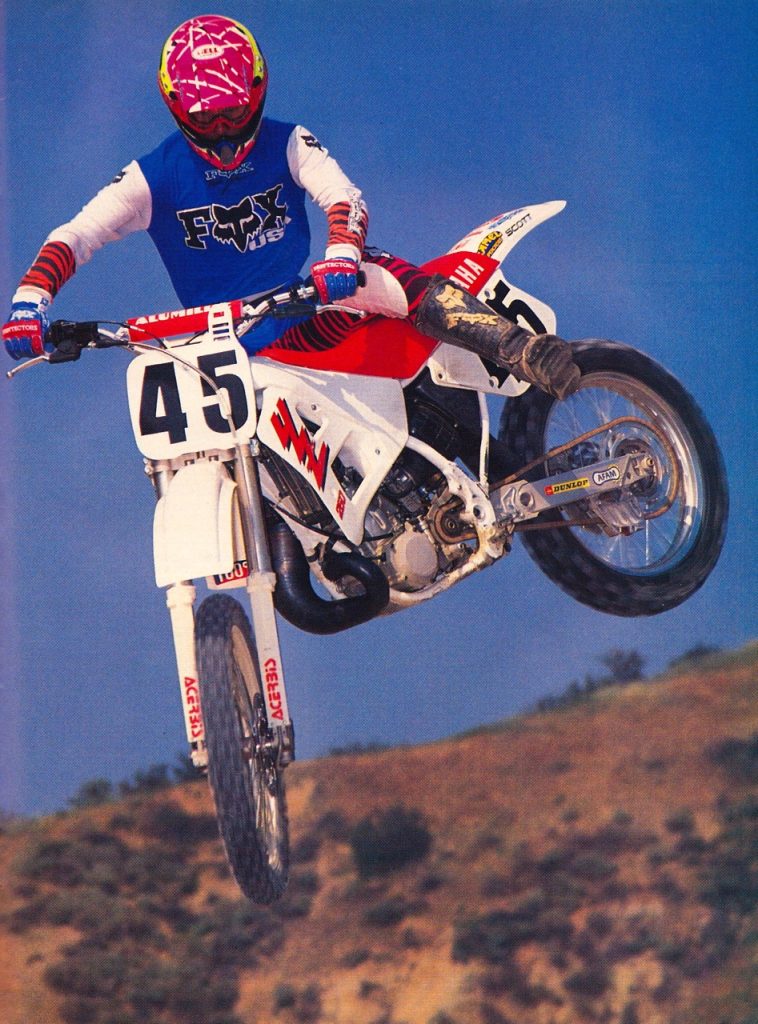

While not quite as feathery feeling as Suzuki’s all-new RM250, the YZ’s excellent ergonomics, snappy motor, and stout chassis made it an excellent aerial partner. Here, Yamaha’s latest hot-shoe Damon Bradshaw demonstrates the YZ’s flickability. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While not quite as feathery feeling as Suzuki’s all-new RM250, the YZ’s excellent ergonomics, snappy motor, and stout chassis made it an excellent aerial partner. Here, Yamaha’s latest hot-shoe Damon Bradshaw demonstrates the YZ’s flickability. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The YZ’s lack of a quick-access clutch cover and a ridiculously undersized oil-fill hole made maintenance more of a hassle than on many of its competitors. Photo Credit: East Coast Vintage

The YZ’s lack of a quick-access clutch cover and a ridiculously undersized oil-fill hole made maintenance more of a hassle than on many of its competitors. Photo Credit: East Coast Vintage

In the end, the 1989 Yamaha YZ250 turned out to be the blueprint for a decade of very effective Yamaha 250 machines. Solid handling, well-sorted suspension, and a flexible motor were the keys to Yamaha’s 250 success in the nineties. Never the fastest, flashiest, or most exciting machine in the class, the Why-Zeds of this era were every man’s machines; bikes capable of winning the in the stadiums and slicing through the trees with equal aplomb. In stock condition, it was a great bike and with a few mods and careful setup, the YZ could be anything you wanted it to be. Ride it, race it, or rip it across the desert, no matter what you had in mind the YZ250 had you covered in 1989.

In 1989, Yamaha hit on the formula that would power their brand to great heights of success in the 1990s. Good motors backed up by a great do-it-all chassis were the keys to making the YZ250 a popular alternative to the fast but often flawed green, red, and yellow machines of the time. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1989, Yamaha hit on the formula that would power their brand to great heights of success in the 1990s. Good motors backed up by a great do-it-all chassis were the keys to making the YZ250 a popular alternative to the fast but often flawed green, red, and yellow machines of the time. Photo Credit: Yamaha

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com