This week’s selection from Greg Primm’s Classic Steel is a real classic, the 1973 Maico 400 Motocross.

By: Tony Blazier

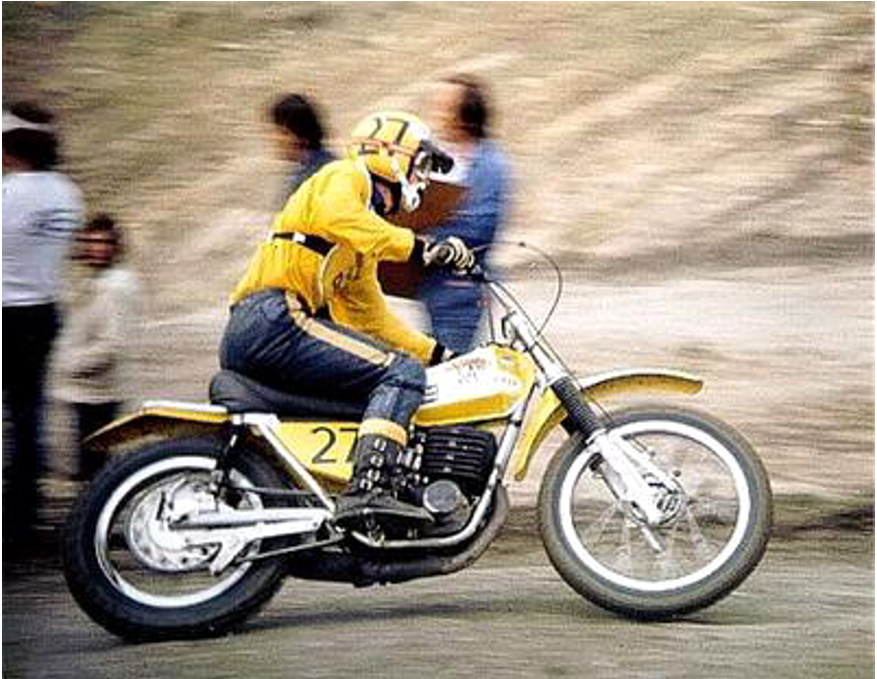

In 1973, the Japanese invasion was not yet in full swing and European bikes like the Maico 400 were the class of the field. The big bore Maicos were known for excellent performance and questionable reliability. If you could keep it in one piece it was hard to beat. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1973, the Japanese invasion was not yet in full swing and European bikes like the Maico 400 were the class of the field. The big bore Maicos were known for excellent performance and questionable reliability. If you could keep it in one piece it was hard to beat. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Maico is one of the names that are synonymous with the early days of motocross here in the US. The German marque was one of the premier brands to own in the seventies and early eighties. In their day, they were some of the fastest and best-handling machines available. Unfortunately, they were also some of the most finicky and fragile bikes you could buy. The phrase “Maico Breako” became a common saying among Maico owners in the seventies. Even with these well-known shortcomings, bikes like the legendary Maico 400 still capture the imagination of classic bike enthusiasts the world over. Fast but fragile, the ’73 Maico 400 is a perfect example of the great European machines of its day.

Although Maico never was able to capture a World Motocross Title, they did capture two Trans-AMA Championships with Swede Ake Jonsson and German Adolf Weil at the controls in the early seventies.

The ‘73 Maico 400 produced a broad, torquey spread of power that was both fast and easy to ride. This smooth, tractor-like power delivery would remain a staple of Maico open bikes throughout the seventies.

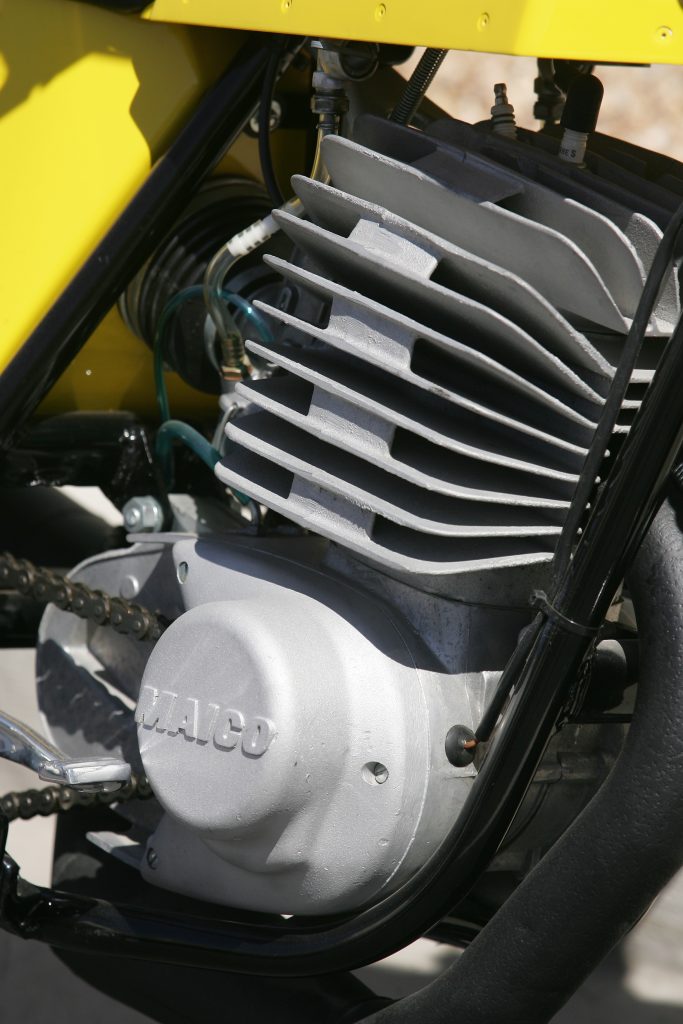

If there is one feature that set Maico’s apart from its competitors, it was their awesome motors. The distinctive radial finned mill produced a broad, easy-to-use powerband that was quite unlike the typical two-strokes of the day. In an era known for hard-to-ride, light-switch powerbands, the Maico’s smooth torque delivery was in a class of its own. Not all was perfect on with the German mill, however. One of the unique features of the Maico was its use of a primary chain to connect the crankshaft to the clutch. This arrangement, while efficient, did cause reliability problems. The chain tended to wear out very quickly, and if not serviced regularly, would fail with disastrous consequences. A thrown chain usually meant an extremely costly repair, including new engine cases. Maicowerk AG, which was founded by Otto and Wilhelm Maisch, started building motorcycles in Germany in the 1930s. During the Second World War, the motorcycle manufacturer was enlisted to build aircraft parts for Hitler’s war machine. After the end of the war, Wilhelm’s involvement with the Nazi party led to his being relegated to a minority ownership position in the company. This was due to post-war anti-Nazi legislation in Germany that dictated that no Nazi party members could hold a majority stake in any German company. Under brother Otto’s leadership, (Otto had stayed out of the Nazi party during the war) Maico would build a reputation for producing fast, sporty street machines throughout the fifties. Many of these lightweight street machines would find their way off-road, due to their versatile two-stroke motors and excellent ground clearance. In the sixties, Maico would start building the off-road machines that would make them famous. They would develop a distinctive look, with their unique “coffin” tanks, leading edge suspension and bright yellow color. By 1973, the big bore Maicos would be the top choice of open class riders in America.

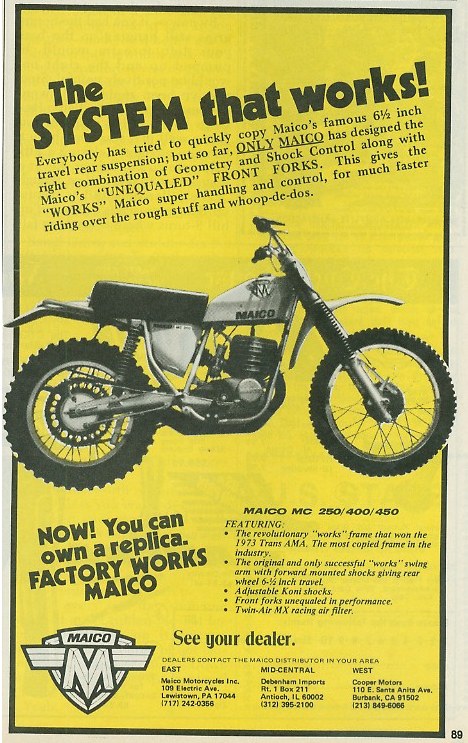

This classic Maico ad from the early seventies proclaims their advanced suspension and excellent handling performance.

Electrical issues were also common in ’73. The sealed, trouble-free CDI ignitions we enjoy today were still years into the future at that point. Instead, points were used to provide the spark for the motor. The points on the Maico suffered the same premature wear issues as the primary chain and if not constantly checked, would wear to the point of fusing together. The result was no spark and another DNF.

The Maico did produced abundant power, but it was temperamental to keep running. There were several issues with the ignition, drivetrain and carburetor, any of which could render the bike immobile without warning. Unlike today’s ride-it-and-forget-it bikes, these machines had to be babied. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Another common problem was chain derailment. The chain and chain guide quality were very suspect on these early Maico’s, leading to many failures. If the chain went, it would invariably shatter the expensive and fragile magneto cover. If none of these maladies struck, you still had to make sure nothing just plain fell off. The bikes were notorious for shaking themselves to pieces. These old air-cooled beasts were shakers, so constant vigilance was required to ensure you ended the moto with as many parts as you started it.

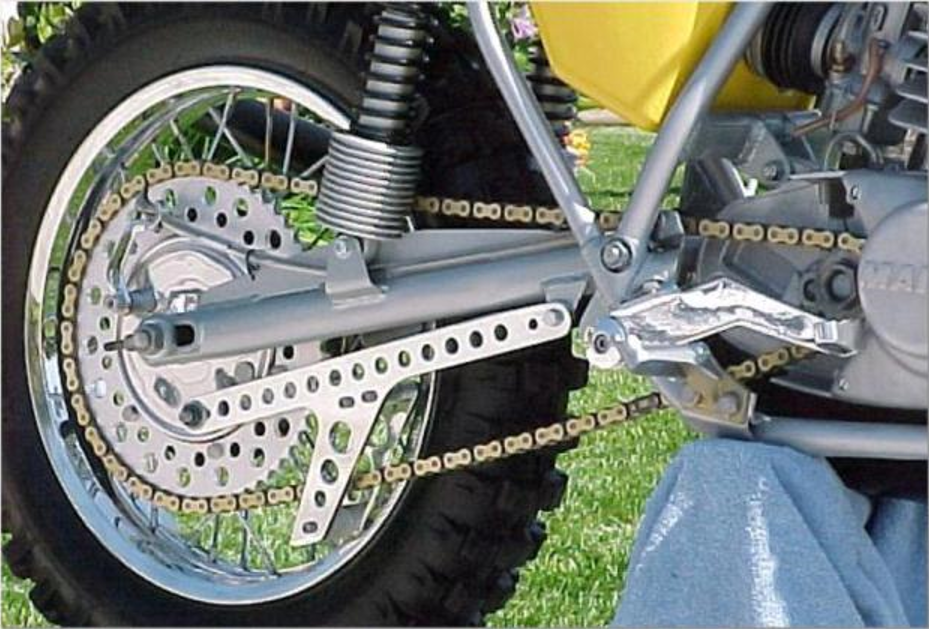

This beautiful Maico is a perfect example of the super trick machines companies like Wheelsmith Engineering were turning out in the early seventies. Wheelsmith could virtually rebuild the entire machine from the ground up to improve performance and reliability.

The Maico’s many shortcomings were so well known, that a cottage industry was built up around improving the German’s many faults. Companies like Wheelsmith Engineering in Santa Ana, California built up quite a business polishing off all the Maico’s rough edges. They could re-spoke the fragile wheels, reline the brakes, and tweak the motor to improve the big Maico’s questionable reliability. In the early seventies, these Wheelsmith Maico’s were the height of cool, with their chrome coffin tanks and trick accessories.

Here is a nice example of some of Wheelsmith’s quality workmanship. This braking torque arm and chain guide combo were both better looking and much sturdier than the flimsy stock unit. Wheelsmith could provide you with everything from a set of footpegs to a super cool, chrome coffin tank to trick out your ride.

One of the reasons these early Maico’s were so popular was their excellent handling. When many bikes of the era were still using inline axle font forks, Maico utilized a leading axle design to improve handling and increase suspension travel. Maico also placed the steering stem in line with the front forks and handlebar to improve steering feel. The fork performance on the ’73 Maico was excellent and far superior to most machines of the day. When you combined the superior handling with the powerful motor and advanced suspension, the performance of the Maico 400 was hard to beat

European open bikes like the Maico 400 were the last holdouts against the Japanese invasion. While the 125 and 250 classes were quickly dominated by the bikes from Japan, Maico open class bikes would remain competitive up until the early eighties. Eventually, their shoddy quality and lack of resources would catch up with them, but for a decade the Teutonic big bores ruled the roost. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Unfortunately, it would eventually be the spotty reliability of the brand that most people would remember. Due to its many issues, the phrase” Maico Breako” will forever be associated with the German marque. In spite of these quality issues, Maico was able to remain successful throughout the remainder of the seventies. Eventually, however, pressure from the Japanese and internal Maisch family financial squabbles would spell the end of Maicowerk AG. In 1983, Maico would file for bankruptcy and in effect end the Maico era in motocross racing. The brand would live on, being sold under the M-Star name and eventually as Maico again, but they would never again see the mainstream success they enjoyed in the 1970s.