With the introduction of the new 2016 YZ250X two-stroke from Yamaha, I thought it might be a good time to take a look back at Yamaha’s first motocross-based off-road racer, the 1989 YZ250WR.

With the introduction of the new 2016 YZ250X two-stroke from Yamaha, I thought it might be a good time to take a look back at Yamaha’s first motocross-based off-road racer, the 1989 YZ250WR.

|

|

In 1988, the Japanese off-road landscape was pretty bleak. Honda’s XR and Kawasaki’s KDX were great play bikes, but neither was prepared to take on the best from Europe. In 1989, all that changed with a pair of serious off-road machines from Yamaha and Suzuki. The new YZ-WR and Suzuki RMX offered different focuses, but neither had to take a back seat to any off-road competitor. |

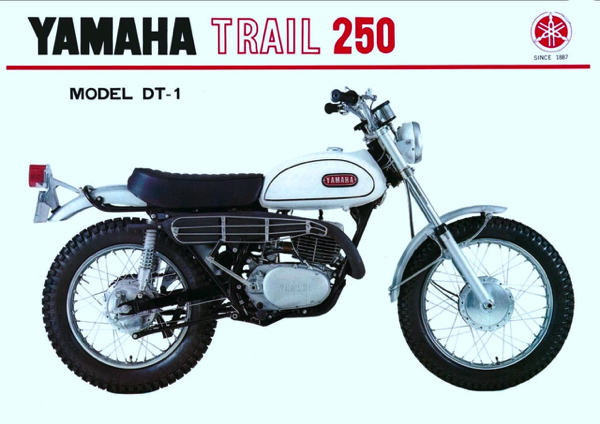

Yamaha’s roots go deep in the world of off-road riding and racing. In 1968, they became one of the first Japanese manufacturers to offer a competitive off-road mount with their incredibly versatile DT-1 250 Enduro. The DT-1 was capable of being raced in motocross, desert and cross-country events with minimal modification and could even be ridden to work through the week. It was the ultimate jack-of-all-trades machine and put Yamaha on the map as an off-road manufacturer.

|

|

Dit-One: In 1968, Yamaha became the first Japanese manufacturer to offer a legitimate off-road machine to the American market. The amazing DT-1 250 Enduro proved to be as adept at racing as it was at playing and became the catalyst for an explosion in off-road interest in America. |

In 1976, Yamaha upped their off-road game with the introduction of their first “serious” off-road racer, the IT400C. The IT (for International Trials) featured a powerful 397cc reed-valve two-stroke single, sturdy double-loop steel frame and a version of Yamaha’s revolutionary Monocross rear suspension system. The IT’s milder power, softer suspension and larger tank made it a better mount for enduro competition than the high-strung YZ and off-road enthusiasts snapped them up in droves.

|

|

International Trials: In 1976, Yamaha launched its first purpose built off-road racer, the IT400C. The IT featured Yamaha’s new Monocross rear suspension, a powerful 397cc reed-valve motor and all the goodies needed for enduro competition. |

After the success of the IT400C, Yamaha would add two new variations for the 1977 season. The all-new IT250D and IT175D built on the formula of the 400, but offered lighter weight and more friendly power characteristics. Both would again employ Yamaha’s race-proven Monocross rear suspension and offer light weight and powerful two-stroke power plants. While perhaps not as capable as the best enduro mounts from Europe, the IT’s proved to be reliable, fun and by far the best Enduro machines from Japan.

|

|

Swan Song: The IT line would have a ten-year run and grow to include models from 125 to 490cc. By 1986, only the IT200 remained and it would be retired at the end of the year. |

In 1980, Yamaha would revamp the IT line with the introduction of a 125cc version for the first time and a bump in displacement to 425cc’s for the IT400. Oddly, the IT425 would only last one year and be replaced in 1981 with the granddaddy of all root-roosting ground-pounders, the mighty IT465. Considered by many to be the best of the Open class off-road Yamaha’s, the mighty 465 would last only two years and be replaced in 1983 with the new IT490. Unfortunately, the 490 suffered many of the same maladies as its motocross brother and most riders found its ponderous ergos, incessant blubbering and annoying pinging difficult to live with.

|

|

Prior to the late eighties, the off-road racing arena was largely the property of the European brands. KTM and Husqvarna dominated the events and were widely acknowledged to produce the best off-road machines available. Honda XR’s, Yamaha IT’s, Suzuki PE’s and Kawasaki KDX’s were all fun and reliable, but not seen as true threats to the Euros. In 1988, Suzuki changed all that by converting an RM250 for off-road use and taking Randy Hawkins to the AMA National Enduro title. A year later, both Suzuki and Yamaha would have off-road racers ready to go toe-to-toe with Europe’s best. Photo credit: Tom Webb |

The 1984 season would see the release of probably the most popular of all the IT models, the beloved IT200. The 200 was light, torquey, well balanced and a solid competitor to Kawasaki’s excellent KDX200. Both bikes were very similar, with the Yamaha offering the more flexible motor and superior front suspension. With the arrival of the new 200, the IT line was trimmed down to just three models, the IT200, IT250 and IT490.

|

|

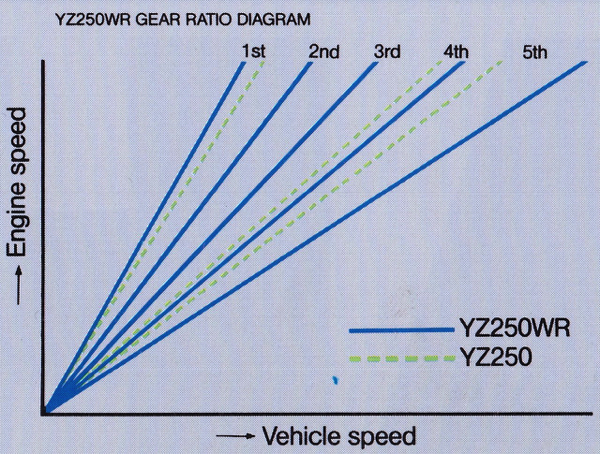

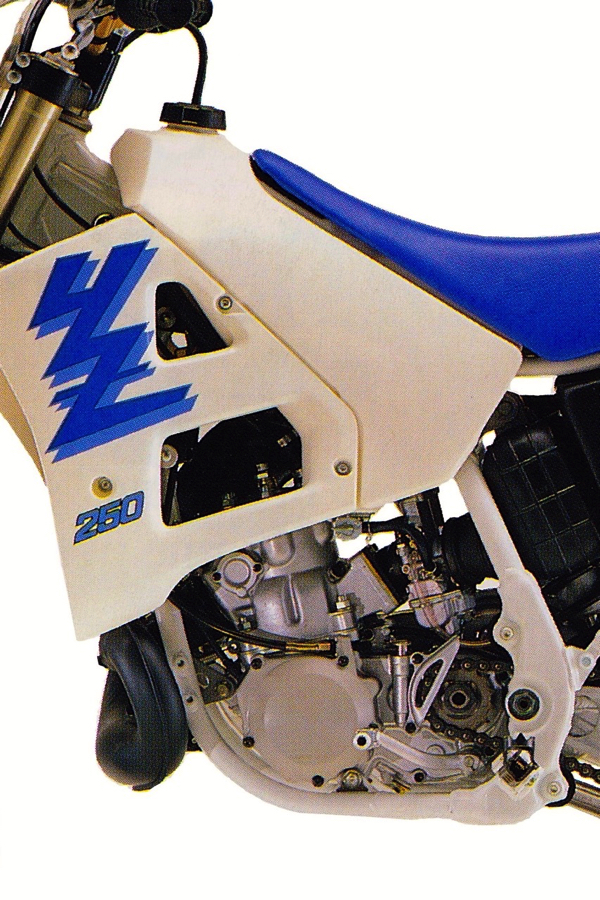

The major difference between the YZ and YZ-WR was the transmission. In the WR, first was lowered, while fourth and fifth were taller. Fifth in particular was quasar fast and the WR could reach nearly 100mph with the stock gearing. |

Sadly, in 1985, Yamaha would retire a further two-thirds of the International Trials line up by axing the middleweight IT250 and portly IT490. This left the IT200 as the sole two-stroke enduro in the Yamaha line up. For 1986, the IT200 remained largely unchanged, but it did receive an upgrade in braking with the addition of a front disc brake. Unfortunately, this would be the last upgrade the IT line would see and at the end of the season, the ten-year run of the popular enduro machines would be at an end.

|

|

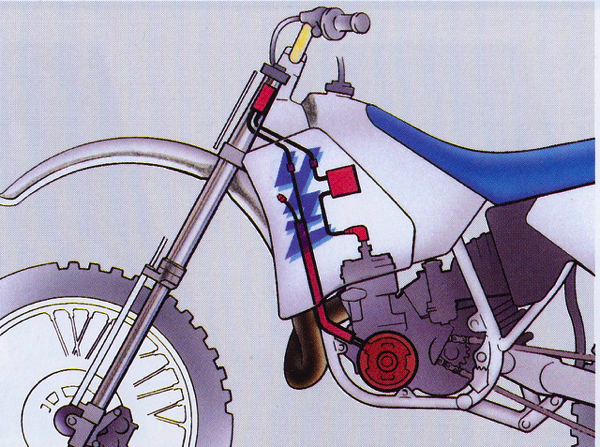

In addition to the different transmission, the YZ-WR carried a 12-volt, 30-watt ignition capable of powering a set of lights. While the bike was pre-wired, the lights themselves were not included. |

After 1986, only the Kawasaki KDX200 remained as a Japanese alternative to the European enduro mounts. Even though there were few off-the-shelf alternatives, that did not mean there were not Japanese machines blasting through the trees back east and across the desert out west. Most common of course, were the converted motocrossers, which could be made into a competitive mount with very little modification. Usually a larger flywheel, bigger tank, re-valved suspension and a spark arrestor were all that was necessary to transform a CR, KX, RM or YZ into a decent off-roader.

|

|

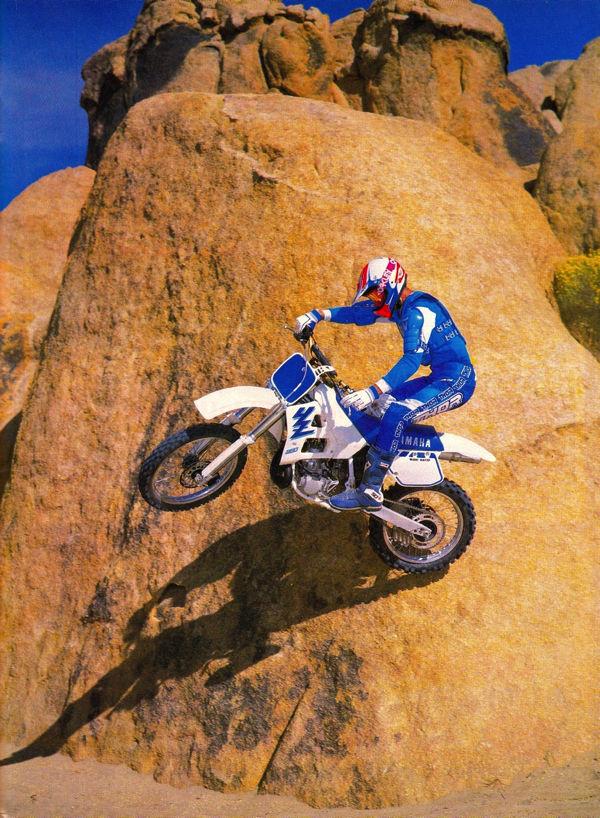

Since the new YZ-WR was 95% motocrosser, it was much happier blasting its way through high-speed desert whoops than picking its way through mud holes. Terry Swanson of Dirt Rider magazine demonstrates. Photo credit: Karel Kramer |

In 1988, talk began in earnest that the Japanese were indeed getting serious again about the off-road racing market. After years of ceding the class to KTM and Husky, both Suzuki and Kawasaki made major pushes with teams racing converted motocrossers against the Euros. This renewed interest would result in Suzuki’s first AMA National Enduro title and an end to Husqvarna’s unprecedented 16-year run of Enduro championships. Randy Hawkins’ win on a converted RM250 (the first of his seven AMA Enduro titles), showed that the Japanese could indeed be competitive in the enduro market if they poured their considerable resources into racing between the trees.

|

|

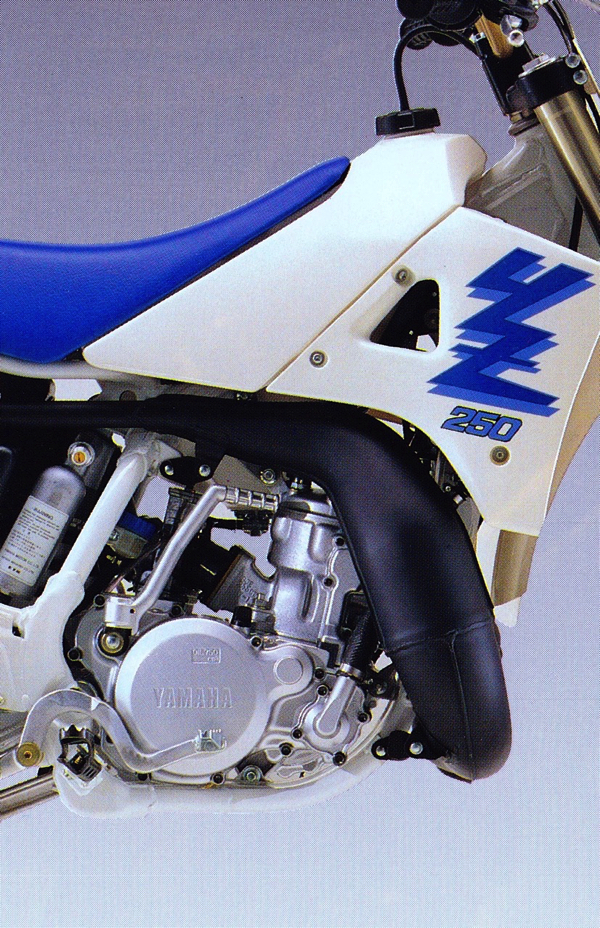

The only concessions to off-road use in the YZ-WR’s power plant were a wide-ratio gearbox and a 10mm larger flywheel. The rest of the motor was pure motocross and WR proved to be the most powerful bike in the class by a wide margin. While this was an advantage out West, in the tight trees and gnarly trails of the East, the WR could be a handful. |

For 1989, both Yamaha and Suzuki would re-enter the off-road market with purpose built racing machines (Kawasaki’s lackluster KDX250 entry would have to wait two more years to make its inauspicious debut). Both the new RMX250 and YZ250WR were based on their manufacturer’s latest motocross technology and miles away from their mild-mannered PE and IT ancestors. While both were based on full-blooded motocrossers, the end product in each case ended up being very different.

|

|

The enduro class of 1989 proved to be an extremely varied group with everything from mild to wild available. On the less serious side, you had the fun and friendly XR250R and KDX200. In the hard-core division, you had the ATK250, KTM 250EXC and YZ-WR. Running right down the middle was the RMX250, which could be as friendly as the KDX or nearly as hyper as the YZ with the removal of a few components. Photo credit: Dirt Bike magazine |

In Suzuki’s case, they went for a full-on enduro bike, with settings and components best suited for racing and riding in the woods. It was based on the all-new ’89 RM250, but it had many features that differentiated it from its motocross sibling. Different porting, a thicker head gasket, a heavier flywheel, wider spaced gears and a choked off exhaust all helped mellow out the RM’s case-reed mill. In addition to these sensible changes, an odd throttle stop was added to the top of the carburetor that prevented full throttle movement. Ostensibly, this was to help make the bike EPA compliant, but in effect, all it accomplished was to make the stock RMX slower than a XR200R.

|

|

An upside-down world: The new for 1989 41mm inverted Kayaba forks on the YZ-WR were the exact same units found on the regular YZ. These cutting-edge components offered more rigidity, less overhang below the axle and by far the firmest ride in the class. Because of their motocross settings, they tended to work much better at big hits than small chop and a revalve was advised if you were planning on racing back East. |

In addition to the motor changes, there were softer suspension settings, an oversize tank, full lighting and quick-detach wheels. While painfully slow in stock trim, the RMX could be transformed by installing a RM head gasket, ditching the boat anchor exhaust and swapping the ludicrous stock throttle stop for an RM part. Once uncorked, the RMX was on par with KTM’s excellent 250 EXC and far faster than the KDX or Honda’s enduro entry, the fun, but woefully underpowered XR250R.

|

|

Ball Buster: One of the complaints about the original YZ-WR was the omission of an oversized fuel tank. The stock 2.1-gallon tank was insufficient for anything besides motocross and any rider planning to race their WR off-road was forced to pop for an aftermarket unit. In 1992, those criticisms were addressed with this bizarre excuse for a fuel cell. Instead of redesigning the entire tank, Yamaha chose to just stick a giant hump on top of the existing design. This new addition was both very wide and positioned in such away as to make future reproduction questionable. One ride was usually sufficient to convince a potential pilot that running out of gas was preferable. |

In direct contrast to the Suzuki approach, Yamaha had done very little to convert their YZ250 to off-road use. The new YZ250WR made no concessions to the EPA and was sold as a closed course only machine. There were no lights (although it was wired to power them), no choked off silencer (or spark arrestor) and no soft springs in the suspension. It was pure motocrosser, with only wider gear ratios, a heavier flywheel and blue accenting to set it apart from the regular YZ. While this meant far more power than the RMX (or any other off-road 250), it also meant far less flexibility in the nasty stuff.

|

|

King Richard: With a skilled pilot like eight-time AMA National Enduro champion Dick Burleson on board, the YZ-WR could be a potent woods weapon, but its potency proved problematic for those of lesser skills. With a revalve, lowered gearing and a heavier flywheel, the WR became a much better companion in the trees. Photo credit: Karel Kramer |

Even with the added flywheel weight, the YZ250WR hit extremely hard for an off-road mount. With its lowered first gear and heavy flywheel, the WR could be ridden in tight and snotty conditions, but care had to be taken to not let it climb on the pipe. If you got in the meat of the power, the WR would most likely light up the tire and send the rear slewing in search of something to roost. By motocross standards, the WR was actually pretty mellow, but by typical enduro bike standards, it was a rocket.

|

|

In the 1989 motocross standings, the YZ250 motor was middle of the pack, with a snappy delivery, but less than awe-inspiring output. It was quick from corner to corner, but not nearly as fast as the Kawasaki or Honda. By far its biggest handicap, however, was its notchy transmission, which made grabbing a gear under power a catch-as-catch-can proposition. In the transition to YZ-WR, none of that personality was really altered, but the change in environment made the bike that felt middle of the pack on a motocross track, seem like a Top-Fueler in the woods. |

Where the WR was most at home was in the desert, where its abundant power and stiff suspension could be put to good use. There, its aggressive motor was an advantage and its wider fourth and fifth gear could be allowed to stretch their legs. Compared to the stock YZ, the WR bumped up the top speed from a motocross track unnecessary 72mph, to an eyeball watering 96mph. This put it on par with other desert speedsters like the XR600R and KX500. The transmission itself offered well-spaced gears, but a notchy engagement that made catching cogs under power difficult.

|

|

While not particularly adept at slimy stream beds and slippery tree roots, the YZ-WR’s snappy power, ultra-light weight and motocross-bred suspension made free riding in the desert a blast. Photo credit: Dirt Bike magazine |

Like the motor, Yamaha’s suspension worked much better in the open than in the trees. The WR’s new 41mm inverted Kayaba forks were identical to the ones found on the YZ and set up very stiff for typical off-road work. In the desert, they allowed the WR to attack sand whoops like a section at Southwick, but at slower speeds, they were busy and unforgiving. In the woods, the low axle overhang of the new inverted forks was a plus, but even with the clickers backed all the way out, you were going to feel every rock and root on the trail.

|

|

Anaheim ready: Like the front, the Yamaha’s Kayaba shock was set up too stiff for enduro use, but excellent at high-speed work. |

In the rear, Yamaha made a bit of a curios choice on the WR by mounting their new 19” wheel in lieu of a more standard for off-road 18” hoop. The 19” inch rear was big news in 1989 and Yamaha was one of the first manufacturers to move to this new size. In motocross, the 19″ offered less sidewall flex, lighter weight and superior cornering feel, but off-road, its increased propensity for flats outweighed its handing and weight benefits.

|

|

Swan song: The WR250 would continue in Yamaha’s lineup until 1998, when it would be replaced with the revolutionary new four-stroke WR400F. |

As to the rest of the rear, it was pure YZ, with stiff valving and excellent bottoming resistance. As with the front, this was advantageous for high-speed work, but less enjoyable back East. Roots and rocks flummoxed its Supercross-bred valving and the WR was much more work than a RMX or EXC. The added flywheel weight helped somewhat with the rear’s tracking in nasty conditions, but it was never going to be as Velcro like as the KDX.

|

|

Probably the most peculiar choice on the new YZ-WR was Yamaha’s decision to mount their new 19” rear wheel on the blue bullet. The 19” offered lighter weight, less sidewall flex and better feel in certain conditions, but paid for it with much poorer resistance to flats. This was a worthy trade off on a motocross track, but made absolutely no sense on a machine made to be ridden in the middle of nowhere. Fortunately, the controversial 19” would only last one year and be replaced with a more off-road friendly 18” rear hoop in 1990. |

|

|

Redux: After a nearly 20-year absence, the beloved Yamaha YZ-WR is making a comeback appearance for 2016. Rechristened the YZ250X, the new Y-Zed is very true to the spirit of the original. More a cross-county racer than a play bike, the X is 90% YZ, with only the barest of modifications made to make it more off-road friendly. |

Overall, the YZ250WR was an incredibly versatile machine and a great starting point from which to build an off-road racer. For desert racing, it had the power and suspension, but you had to spring for your own lights and a bigger tank. Back East, it would really need a revalve and a switch to an 18” rear would be wise, but if you were fast enough to effectively use its power, it was a great GNCC machine. It was certainly not the play bike the IT had been, and for those looking for a fun woods mount, the XR or KDX would have been a much better choice. If, however, you were looking for a bike that could be raced in a Hair and Hound, taken to the MX track and then carted off to the hills for a ride with your buddies, the 1989 Yamaha YZ250WR was hard to beat.

|

|

The 1989 Yamaha YZ250WR was a bike Japanese off-road enthusiast had been waiting two decades for; a hard-core off-road racer that put performance and speed above comfort and ease of use. It made no concessions to the EPA and left some of the final assembly up to the buyer, but it made an excellent foundation for an off-road racer. |

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier