For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the first production 125 to incorporate a Power Valve, the 1982 Yamaha YZ125J.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the first production 125 to incorporate a Power Valve, the 1982 Yamaha YZ125J.

|

|

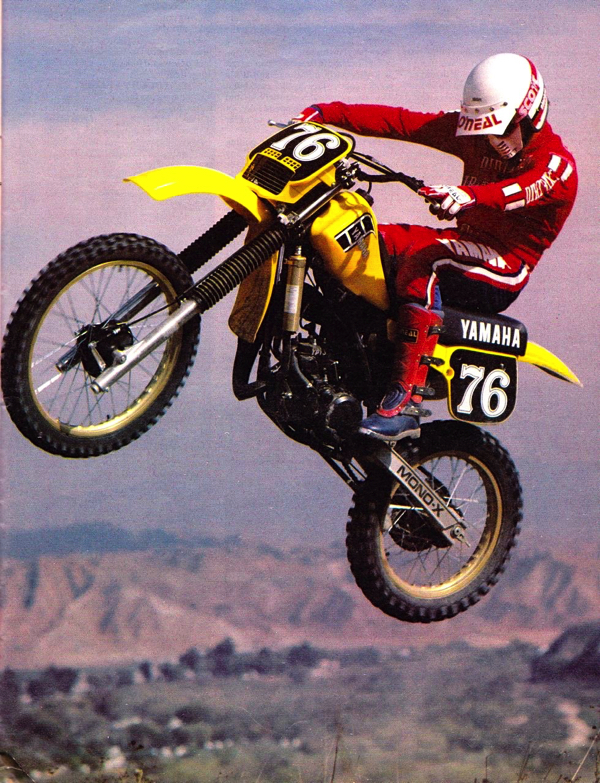

In 1982, Yamaha introduced an all-new 125 that placed the YZ at the very cutting edge of motocross design. Its new linkage equipped Mono-X rear suspension and powerful Power Valve motor signaled Yamaha was committed to wresting back the title of best 125 in the land. |

In the early eighties, motocross technology was moving at blinding speed and in no class was this relentless march of progress more apparent than the 125 class. Unlike today, where a five-year old machine gives up virtually nothing in performance, in 1982, a 125 from only three years prior was considered virtually obsolete. The advent of water-cooling, beefy forks and rising rate suspension systems meant that the performance potential of stock 125’s was surpassing that of works bikes from only a few years before. Each new model brought with it innovations and real improvements that pushed racing technology ever further.

|

|

In 1975, Yamaha introduced the world to the joys of long-travel suspension with their YZ and MX line (1975 Yamaha MX250 pictured) of motocross machines. At the time, the new monoshock offered double the suspension travel of traditional rear suspension designs. Yamaha would continue to use and refine this basic design into the next decade. |

In 1980, that leap in technology had come from Kawasaki with their new Uni-Trak rear suspension system. The first of a new wave of single shock rear suspension designs, the Uni-Trak mounted a single shock behind the airbox and attached it to a bell-crank that varied the speed of the shock through its travel. By varying the force put on the shock, the rising rate linkage (first generation Uni-Trak models offered no rising rate due to patents on the design in America) allowed (at least in theory) the designers to deliver a supple ride at low speeds, while maintaining suitable bottoming resistance.

|

|

In 1982, Yamaha would introduce the first major revision to their monoshock rear suspension since its inception. The new Mono-X rear maintained the shock placement of the original, but mounted it to a new rising rate linkage and redesigned swingarm. |

For 1981, the major technological advance was liquid cooling. Used on factory bikes on and off since the mid-seventies, water cooling allowed the motors to be built in a higher state of tune, while also offering increased longevity. Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki all introduced water-pumping 125’s in 1981, with Kawasaki remaining the last air-cooled Japanese holdout. In addition to the liquid cooling, both Honda and Suzuki jumped on the rising-rate bandwagon with single-shock suspensions of their own. The introduction of the new Pro-Link (Honda) and Full-Floater (Suzuki) systems meant Yamaha was the last manufacturer in the class not using a works-style rising rate rear end design.

|

|

1982 was a year of major innovations for Yamaha and the new YZ125 and YZ250 featured the industries’ first “safety seat” up-the-tank saddles. |

The 1982 season would bring with it the third major advance in three years to the 125 class – the Power Valve. This time it would be Yamaha on the cutting edge of design, with the introduction of their Yamaha Power Valve System (YPVS). The YPVS consisted of a rotating drum built into the front of the cylinder, which was actuated by a set of linkage and a centrifugal ball governor. The drum was placed at the top of the exhaust port and raised or lowered the port height based on engine rpm. At low rpm, the crescent shaped drum extended down into the exhaust port, lowering port height to increase low-end power. As rpm’s rose, the centrifugal ball governor rotated the drum to uncover the exhaust port for better flow and increased top end power.

|

|

In addition to the new chassis and suspension, the 1982 YZ125 would feature an all-new motor that incorporated a “Power Valve” the first time. First seen on works bikes only a few years prior, Power Valve was designed to widen the traditionally narrow two-stroke power spread by adjusting port timing to best suit engine rpm. Yamaha named this new technology the YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) and it consisted of a small drum placed at the top of the exhaust port, which was rotated based on the action of a small centrifugal ball governor. Depending on engine rpm, the exhaust port height could be raised or lowered by rotating this drum to fine tune performance and widen the available spread of power. |

Before the invention of the Power Valve, it was necessary to tune the bike to run best at a specific rpm. If you ported it for low-end power, it tended to be choked off on top-end and if you designed it to run well of top, it typically was going to be soft down low. With advent of the Power Valve, it was possible to design a two-stroke that could excel all three stages of the power curve. While it would take the manufactures several years to make the most of this innovation, the introduction of the original YPVS was a major step in motocross technology.

|

|

From 1975 through 1984, YZ models came in two flavors. Depending on where you lived, your Yamaha race bikes either came in yellow and black (North America) or white and red (International). In 1985, the US bikes adopted the international white color scheme for the first time (Canada made the jump in 1982). The YZ’s would remain mostly white (with brief flirtations with pink and lavender) until the switch to blue in 1996. |

|

|

In 1982, this 123cc missile was the fastest motor in the 125 class by a wide margin. The YPVS equipped mill was only mediocre down low, but it ripped through the middle and wailed on top. Even with its weight disadvantage and tall stock gearing, the little YZ was more than a match for all comers in 1982. |

With the introduction of the 1982 YZ125, Yamaha would once again show that they were at the cutting edge of motocross design. The had been one of the first manufacturers to embrace the reed-valve intake and their original monoshock design had taken the world by storm in 1973 on Håkan Andersson’s works YZ637. Based on a design by Belgian engineer Lucien Tilkens, the original monoshock had offered twice the suspension travel of bikes in its day.

|

|

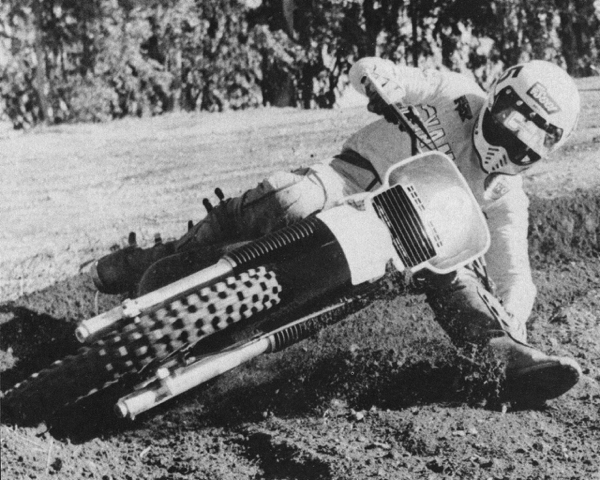

While the new YZ’s motor was more than up to the challenge in 1982, the rest of the package was in need of a little fine tuning. At 218 pounds, the bike was nearly 30 pounds heavier than the lightest bike in the class. While trick, the safety seat and large bulbous tank also made sliding forward in turns difficult. Overall, the new YZ had a large and bulky-like feel that most 125 pilots did not enjoy. Photo credit: Motocross Action |

The monoshock would first see production on the 1975 Yamaha YZ250B and lead to a suspension revolution in the late seventies. Within three years of the mono’s introduction, every bike on the track had more than doubled its available suspension travel and by the end of the decade, most were clocking in at a full 12 inches front and rear. With the introduction of the new rising-rate designs in the early eighties, however, this suspension war turned from raw travel numbers to quality of action. Just having the most was no longer enough to garner headlines; it had to be good travel as well.

|

|

Some of the blame for the YZ’s portly feel went to the design of its cooling system and suspension. Both the new Mono-X and the motor’s liquid cooling hardware carried most of their weight high on the chassis, where it most adversely affected handling. |

In ’80 and ’81, Yamaha stuck stubbornly with their original monoshock design, in spite of the advances of the competition. While competitive in terms of travel (11.8 inches), its performance was quickly getting outclassed by the competition. The Mono-X worked well when ridden hard, but kicked and hopped in the rough and was generally much less plush than the rising-rate competition. In 1980, the Mono had been competitive, but by ’81, the new designs had relegated the YZ to back-of-the-pack. For Yamaha, it was becoming apparent a major upgrade to the rear suspension was going to be necessary to keep pace in the hotly competitive 125 class.

|

|

Ponderous: On the track, the husky-sized YZ felt more like a slow 250 than a ripping snorting 125. |

For 1982, that upgrade would come in the form of the first major redesign of the Mono-X since its inception in 1975. The new Mono would retain the shock placement of the original (laid down, below the gas tank and running the length of the frame backbone) and be bolted to an all-new frame. The large triangulated swingarm that had become a Yamaha staple since the early seventies would finally be retired in favor of a traditional boxed aluminum unit. Connecting the new frame, swingarm and shock would be a large rocker arm and a single pull rod, which changed the leverage ratio of the suspension as it moved through its stroke.

|

|

While providing the YZ with the most horsepower in the 125 class, the new YPVS motor was far from perfect. Clutch life was paricularly poor and the new Power Valve motor suffered several first year teeting problems. |

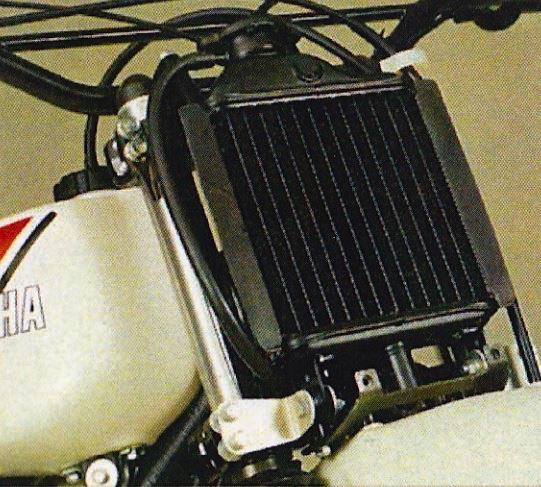

Finishing off this high tech package would be all-new bodywork that marked the first major departure in YZ styling since the mid-seventies. Gone were the round numberplates and long rectangular tank, to be replaced with a works-style up-the-tank saddle and freshened look. The new bike would retain the ‘81’s triple clamp mounted radiator, but ditch its oddball looking ram-scoop front plate in favor of a slightly less bizarre looking vented cover.

|

|

When developing their first rising-rate linkage, Yamaha tried to graft the new technology on to their existing design. The result was a disappointing combination of old and new that offered little or no advantage over the simpler system it replaced. This design would only last one year and be replaced by a system similar to Honda’s Pro-Link in 1983. |

On the track, the YZ’s new 55mm x 50mm 123cc two-stroke mill was by far the fastest motor in the class. Despite of the addition of the YPVS, the YZ remained pretty mediocre off idle (better than 1981, but nothing sell your Maico 490 over), but once the Power Valve snapped open, the little YZ hit the afterburners. Midrange power was extremely potent and YZ just kept pulling and pulling until the other bikes were in its dust. Drawing fuel through a 34mm Mikuni carb and a six-peddle reed-valve, the YZ was able to put several bike lengths on its competitors on any decent sized straight. Even with its absurdly tall stock gearing, the potent Yamaha was head-and-shoulders faster through the gears than any other ’82 125.

|

|

One of the rising stars in 1982 on the all-new YZ125 was Ronnie Lechien. Ronnie would turn pro in 1983 and take his Factory Yamaha to three 125 National victories. Dirt Bike Magazine Photo |

While the new motor was a rousing success, not all the changes yielded similar results. In the switch from ‘81 model to ‘82, the YZ125 picked up six pounds of unwanted baggage. Additional bracing for the frame, the YPVS, a bigger tank and the new Mono-X were blamed for the added poundage. This put the YZ at 218 pounds, a whopping 26 lbs. north of the featherweight RM125! Even worse, all of this weight was carried very high on the chassis.

|

|

In 1982, all the manufacturers had very different ideas about the best design for liquid cooling their motors. In Yamaha’s case, they went with a single large radiator that was mounted to the front of the triple clamps. Coolant was pumped to the radiator by a series of hoses that ran through the frame to fittings mounted on the clamps. While innovative, it proved less advantageous to handling than other systems that carried the cooling hardware lower on the chassis. |

In the transition to the new Mono-X, Yamaha had chosen to stick with the same basic shock placement they had used since 1975. While this allowed them to leverage a decade of development, it unfortunately did nothing for the YZ’s chassis dynamics. The large and heavy DeCarbon shock used on the YZ ran basically the whole length of the bike and was placed up high under the tank and seat. This made the bike both wider and less nimble that the competition.

|

|

One highlight on the new YZ was its well reviewed forks. The 38mm Kayaba’s offered 11.8 inches of travel and were rated the best legs of 1982. |

The other issue with the YZ’s handling was the design of the cooling system. In 1982, all the 125’s were liquid cooled, but all four used completely different systems. Just as with the rear suspension, no one manufacturer had nailed the optimal design and all four were experimenting with the best configuration. In Yamaha’s case, they had gone with a single radiator mounted to the front triple clamps. A series of hoses piped coolant from the motor through the frame and up to radiator, which was mounted where a traditional front numberplate would sit.

|

|

Yamaha had used this large triple clamp mounted radiator design on all its liquid-cooled race machines since Bob Hannah’s OW27 in 1976. While less prone to crash damage than competing designs, issues with seal leakage, weigh and handling would lead the Tuning Fork Company to adopt a Honda-like arrangement in 1983. |

|

|

If pigs could fly: The weight and overall size of the YZ made it the least nimble flyer of the 125 crop. Gentleman Jim Holley bravely temps fate on the new YZ. Photo credit: Dirt Bike Magazine |

This placement meant that a great deal of heavy hardware was hung right off the bars, where it was most noticeable. This design, combined with high-mounted shock, gave the pudgy YZ a very top-heavy feel. Anyone jumping on the bike was immediately aware of the extra weight on the front end and it made the YZ feel floppy in turns. In turns of outright cornering, the YZ was passable, but nothing more. Front traction was good, but when it came time to change direction, it was more sluggish to respond than the other machines in the class. High-speed stability was marginal as well, and the little Y-Zed liked to shake its head at speed.

|

|

Dirt Bike Magazine’s Paul Clipper, Tom “Wolfman” Webb and Rick “Super Hunky” Sieman try to decipher the new YZ’s secrets in 1982. Photo credit: Dirt Bike Magazine |

In terms of shock performance, the new Mono-X suspension was a slight improvement, but far from the best performer in the class. One knock on the original Monoshock had always been its lack of progressiveness. It worked well on hard hits, but was harsh and prone to deflecting on smaller impacts. By switching to a linkage suspension, it was hoped some of this would be lessened, but the new Mono-X turned out to be more-or-less the same mediocre performer it had been the year before.

|

|

The new Mono-X rear in the YZ turned out to be a massive disappointment. It was harsh on small bumps, too soft on big hits and prone to kicking under deceleration. Overall, it was rated as the poorest rear end of ’82. |

|

|

Ripper: The new YZ wasn’t just a little bit faster, it was head-and-shoulders faster than any other 125 of ’82. By fourth gear, the YZ would put two-three bike lengths on every other machine in the class. Photo credit: Motocross Action Magazine |

In order to smooth out the low-speed ride, Yamaha spec’d out a fairly soft spring on the new Mono. Unfortunately, this did little for the rear’s plushness, while leading to sever bottoming on hard hits. Its mild linkage curve, too-soft spring and poorly chosen valving beat your backside on chop and hammered your spine on big hits. It was harsh on small and large impacts alike and still wanted to kick under deceleration (hello Yama-Hop, my old friend). Although the kicking was lessened somewhat by the new rising-rate linkage, it was still the same Yamaha bugaboo it had been since the monoshock’s intro. Overall, the new Mono-X was too heavy, too bulky and the worst rear end of 1982.

|

|

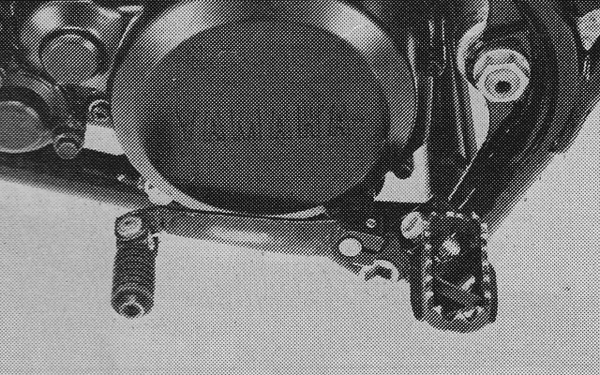

The folding shifter was a nice touch, but the instantly drooping footpegs left a lot to be desired. |

Up front, the story turned out to be much better for the new the YZ. The Yamaha’s Kayaba forks punched out 11.8 inches of travel and offered air adjustability/oil adjustability only. At 38mm in diameter, they were small compared to the 41mm units found on the Kawasaki, but were comparable to the forks found on the Honda and Suzuki. Action was not particularly plush, but the same could be said of most damper-rod forks of the era. They reacted well to most track obstacles and did a decent job of soaking up hard hits. While not spectacular, they were still rated the best of a mediocre field.

|

|

While the YZ250 and YZ490 got the high tech dual-leading shoe front binder, the 125 had to make due with old fashioned single action brakes. |

In the details department, the YZ had a few teething problems in 1982. The pegs were of dubious quality and started drooping before the second tank was spent. Bars were butter soft and the control levers preferred to snap off rather than be bent in a crash. Stock gearing was set up for Bonneville and the YZ needed at least two teeth on the rear for anything short of desert racing. The pipe was a leg roaster and enjoyed melting holes in the sidepanel. While the new safety seat was certainly cool, the overall ergonomics were bulky and the YZ was by far the biggest feeling of the ’82 125 crop.

|

|

In 1982, MXA took things a bit less seriously than they do today. Photo credit: Motocross Action Magazine |

There were also a few problems in the motor department. Some of the centrifugal ball governors developed grooves in their outer channels that caused the YPVS to stick open (goodbye low-end). In some cases, the linkage arms that controlled the YPVS were also known to bend. Once this happened, the Power Valve failed to open and close properly and performance became erratic. Because the coolant was piped through the frame to the radiator, leakage became an issue and weeping seals were common. Lastly, the clutch was not a fan of abuse (not a great quality on a 125) and it became a grabbing and lurching mess if pushed.

|

|

In 1982, Yamaha threw a lot of technology at the 125 class. Their high tech motor produced the most power in the class and their new Mono-X rear finally brought the YZ into the modern suspension age. While full of potential, the new Yamaha tiddler was fraught with first year teething problems and unfortunate design choices. It was a machine in need of a diet and a major does of refinement if it was going to challenge for top 125 in the land. |

Overall, the 1982 YZ125J proved to be a bit of a mixed bag of brilliance and blunder. By playing it safe and trying to squeeze one more year out of their original monoshock design, Yamaha ended up with a heavier and more complex design, which was not appreciably better than what it replaced. The weight, size and overall bulk of the new YZ held it back in every category except horsepower, where its high-tech motor had the competition covered. If it had the finesse to go with its pony prowess, it would have been a world-beater, but as it was, it was a hot rod in need of finishing school.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier