Next level.

Next level.

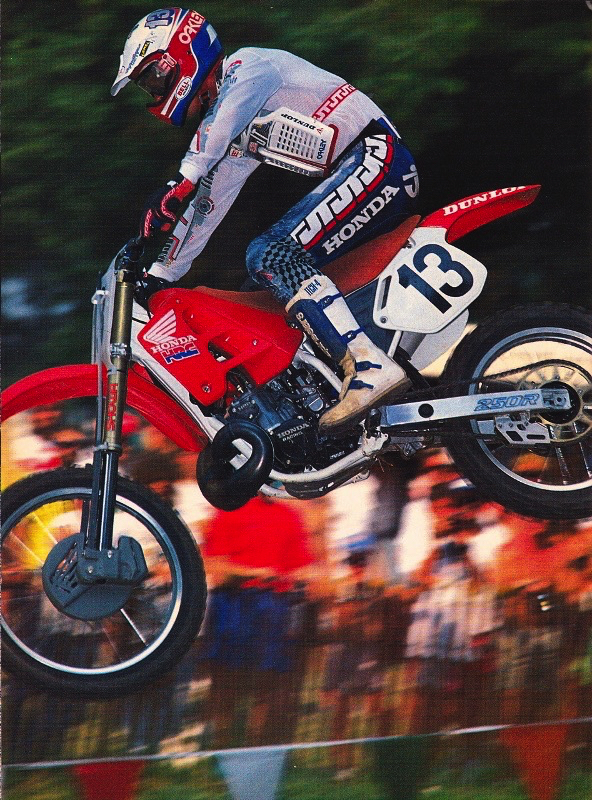

For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the bike that took Jeff Stanton to the second of his three AMA Supercross titles, the 1990 Honda CR250R.

|

|

For 1990, Honda looked to bring back a little of their mid-eighties magic with all new bodywork, major power refinements and switch back to the orange mist of the ’83 to’87 CR’s. Unfortunately for consumers, however, a switch back to the ’87 CR’s forks was not on the menu. |

In 1989, Honda caused quite a stir inside the motocross industry by dramatically raising the cost of their entire motocross line. For ’89, the cost of the CR250R jumped over 20%, to a then unheard of $4000. This was a huge increase at the time and shocked a public accustomed to $2000 125s and $3000 250’s. Part of this increase was blamed on a weak Yen in Japan and part of it was ascribed to Honda’s decision to equip the new CR’s with Showa’s new works-like USD forks. These 45mm units were considered incredibly trick in 1989 and looked to have been pilfered right off of Ricky Johnson’s ’88 works bike.

|

|

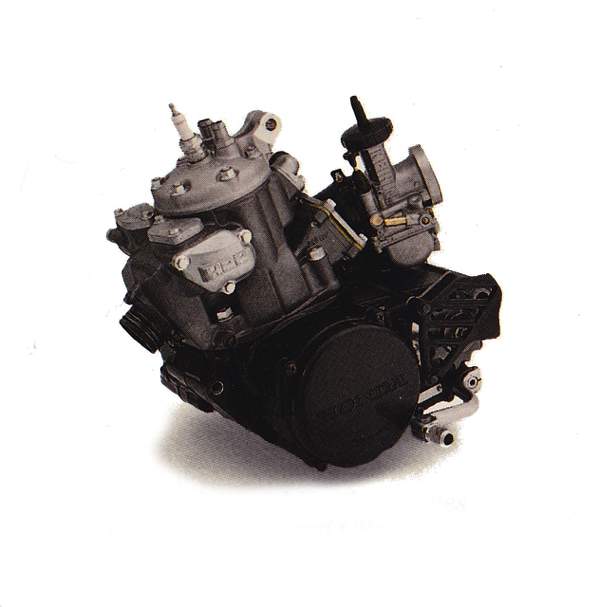

In 1986, Honda Motor Corporation introduced one of the most dominant two-stroke motocross engines of all time. Powering Honda CR250R’s from 1986 until 1991, this 249.3cc wonder cranked out beaucoup ponies over an incredibly wide spread. Both easy-to-ride and blazing fast, no other 250 was even close. |

The new CR250R was the priciest bike in the class by $300-$400, but it was also the fastest, sharpest handling and best built. Unfortunately, the blood-red Honda was also the worst suspended by a country mile. The ultra-harsh Pro-Link shock refused to move on anything smaller than a Supercross whoop and the new high-tech Showa forks proved virtually unridable in stock condition. These new forks looked trick, but they were incredibly harsh in the mid-stroke and prone to bottoming with a tooth-rattling clank on even medium sized jumps. By mid-season, Honda was forced to acknowledge that they had a problem and actually issued a recall on the offending forks and started offering cash rebates on the CR’s (unheard of at the time). New top out cones were installed at no additional cost and a tiny bit of the mid-stroke harshness abated, but they remained the worst forks in the class by a wide margin.

|

|

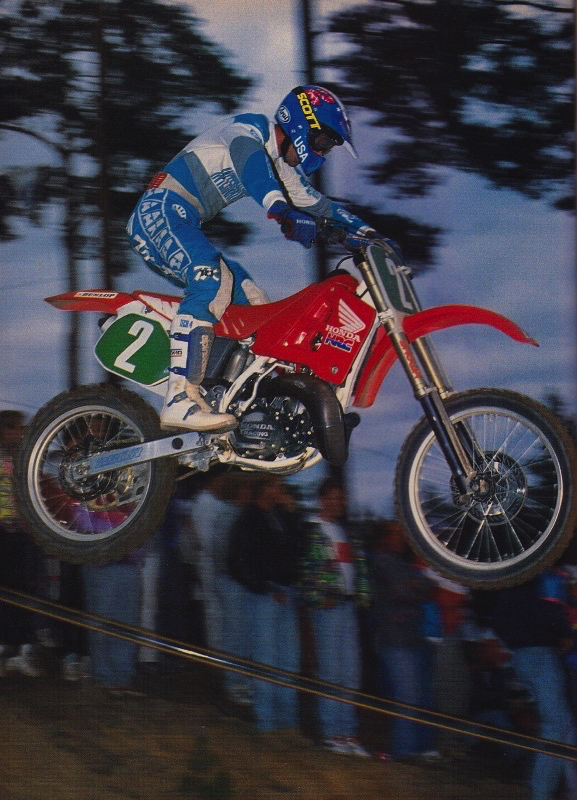

The 1990 season was a tough one for one of the sport’s greatest champions. In 1989, a broken wrist had taken Rick Johnson down at the absolute zenith of his powers and opened the door for a new star under the Honda tent. For 1990, Rick was back and hungry to reclaim the number one plates that Jeff Stanton had captured in his absence. Johnson struggled mightily during the ‘90 Supercross season and looked like a mere shadow of his formerly dominant self. In the outdoors he would fare better, claiming victories at both Gatorback and Unadilla, but continue to suffer the lingering effects of his ’89 wrist injury. The seven time AMA champion would only make it a few rounds into the 1991 season, before officially announcing his retirement at the Daytona Supercross. Photo credit: Motocross Action |

After the fork and sticker shock debacle of 1989, Honda realized that they needed to do something about their quickly tarnishing suspension reputation. In 1986 and 1987, they had ruled motocross with amazing packages, topped by the best forks in motocross. In 1988, poor setup had derailed suspension dominance and then in 1989, the train had officially jumped off the tracks. If they were going to ask a substantial premium for their products, then they could not continue to deliver bikes that demanded another $500 be spent at the suspension tuner before they could even be ridden.

|

|

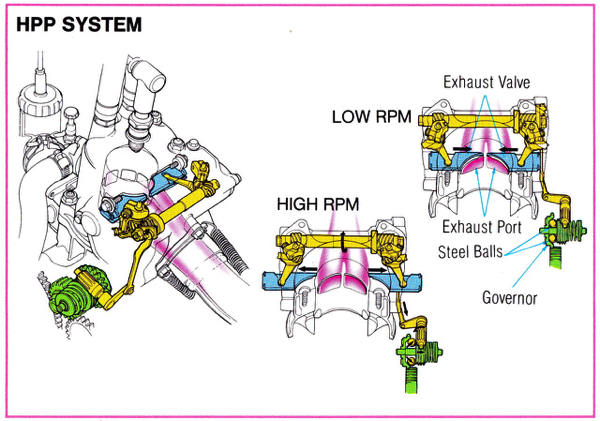

Honda’s HPP (Honda Power Port) system was one of the first “Power Valve” systems to truly make good on the promise of a wide and easy to use two-stroke powerband. Using a pair of sliding guillotine valves actuated by a system of levers and linkage arms, the HPP varied the exhaust port height based on engine rpm to provide a wider powerband. Similar in theory (if not design) to Yamaha’s original YVPS (Yamaha Power Valve System), the Honda version offered better sealing and superior performance. Its only real downside was its complex design, which made regular maintenance a chore. |

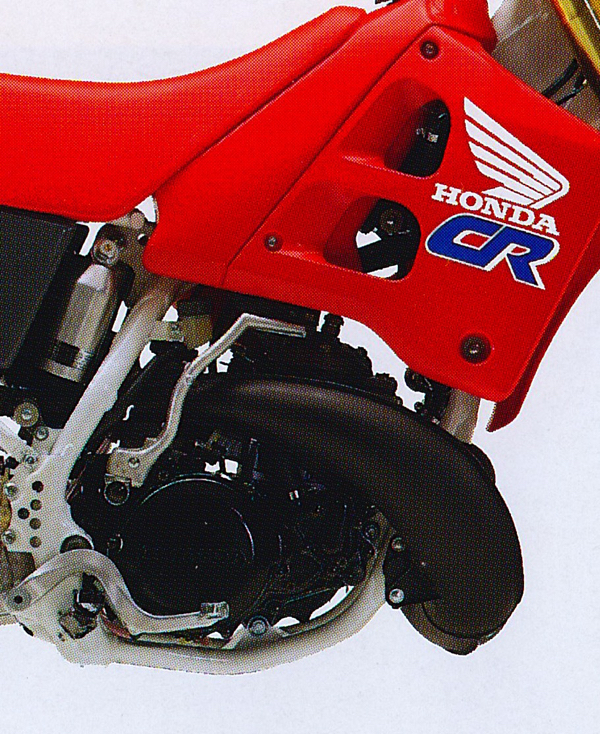

For 1990, Honda looked to address these and several other issues with a virtually all-new CR250R. A new frame looked to quell some of the ‘89’s violent headshake and all-new bodywork offered a flatter rider compartment and smoother movement fore-to-aft. A new linkage and revised internals for the 45mm Showa’s promised a more compliant ride, while several motor changes looked to broaden the power on the ‘89’s hard-hitting mill. Topping off the new package was a switch back to the ’83- ’87 CR’s “orange mist” color scheme and a very un-Honda like coat of white paint for the frame.

|

|

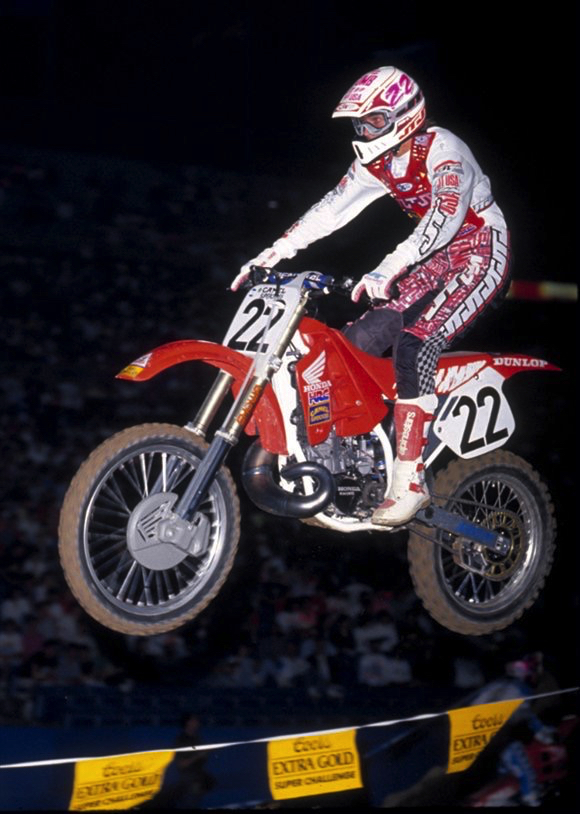

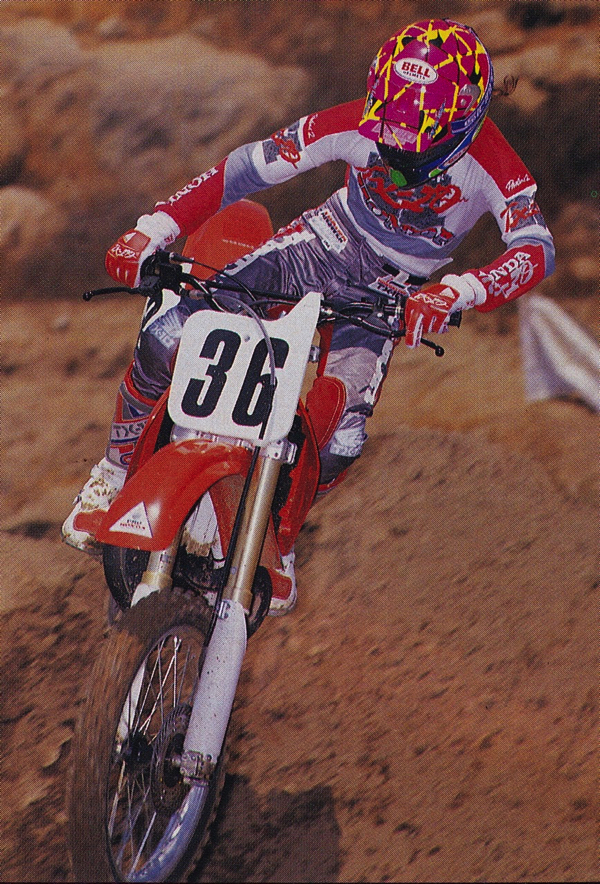

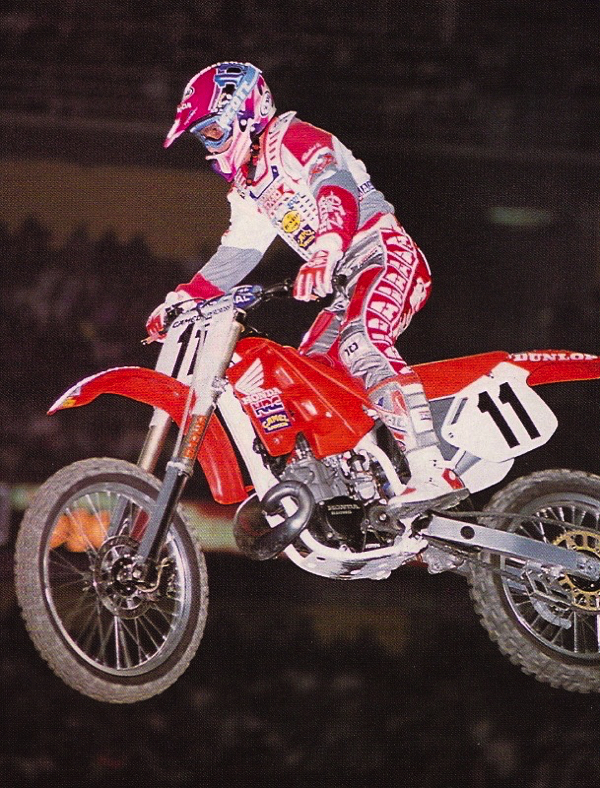

Visually Jeff Stanton’s 1990 Factory Honda did not differ greatly from the stock CR250R. After the passing of the production rule in 1986, the factories were no longer allowed to race the ultra-exotic mega-bucks works specials of the early eighties in the AMA series. Factory Showa suspension, careful setup and meticulous attention to detail were the main advantages Jeff’s bike had over the garden variety CR. Photo credit: Dirt Bike |

|

|

Shake and bake: For 1990, Honda made several changes to the CR’s chassis aimed at taming its notoriously spooky high-speed manners. A repositioned motor, reinforced and relocated steering head and revised geometry were mated to a fresh coat of white paint for the frame. In spite of all these changes, the new-look CR remained largely the same tight handling and twitchy machine it had been since the early eighties. |

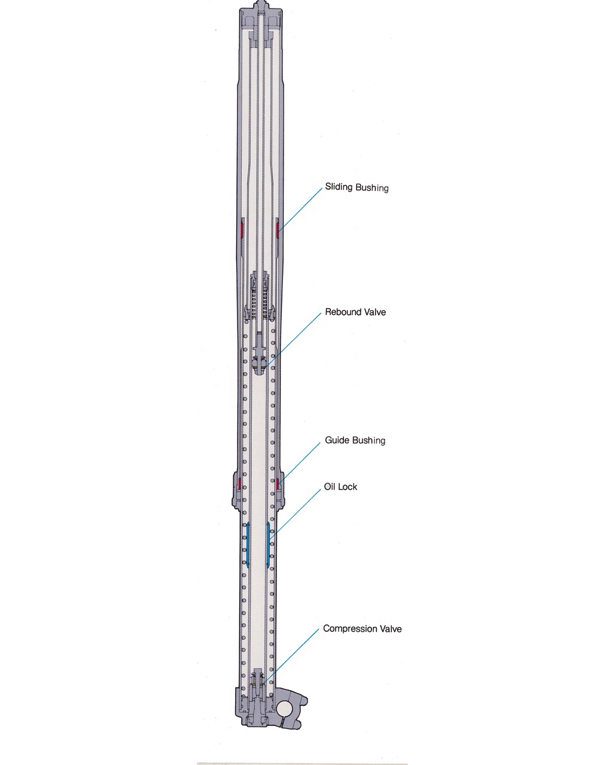

Usually, the first question anyone asks about a new bike is “how fast is it?” In 1990, however, that was not the case. With the new CR250R, the only thing potential buyers wanted to know was whether or not the Honda had finally fixed the forks. To that end, Honda completely redesigned the internal workings of their critically assailed 45mm inverted Showa forks. A new oil lock system was spec’d to smooth operation and fight bottoming, while new guide bushings sought to reduce stiction. According to Honda, stiction was a major culprit in the harshness of the ‘89’s front end, so they went on an all out war to reduce friction in the fork. The new bushings were 5mm shorter for ’90 and now featured oil passages to reduce drag. The outer bushing now featured a tapered bore for smoother action and a double clamp axle was added to the increase torsional strength and prevent binding. Showa even developed a special fork fluid (SS-7M) for the CR’s that they claimed reduced friction by 30%.

|

|

Un Perfecto: In 1990, the Honda CR250R punched out a nearly perfect motocross power curve. Torquey down low, brawny through the middle and capable of revving to the moon on top, the CR was both incredibly smooth and blazing fast. |

|

|

In 1990, two-time World Motocross champion Jean-Michel Bayle made the jump to race in America full time. He would end up tying Damon Bradshaw for the most victories in the 1990 season (five apiece) and finish second in the final standings behind his Honda teammate, Jeff Stanton. Photo credit: Motocross Action |

On the track, the new forks were substantially better than the atrocious ’89 units, but still poor by any other standard. Action continued to be harsh and the stiction was back, in spite of Honda’s many efforts to remedy it. As delivered, the forks were set up with light springs and heavy damping. This made them harsh on small hits, while still prone to metal-to-metal bottoming on big impacts. Small chop was transmitted right to the rider’s wrists and there was a nasty spike in the mid-stroke. The overly soft springs also caused the front-end hang down in the travel and contributed to an unbalanced feel that only exacerbated the bike’s spooky high-speed manners.

|

|

Return to sender: In 1989, Honda had major league problems with their all-new 45mm inverted Showa forks. Customer complaints were so vociferous about their abysmal performance that Honda actually issued a recall mid-season to update the bottoming cones for smoother action. For 1990, a new oil lock system was employed and mated to revised valving and new low friction bushings in hopes of alleviating some of the harsh action. |

Worst of all, though, were the Showa’s problems with particulate contamination that quickly took their performance from merely awful to practically medieval. Even with the new tapered seals, there continued to be a lot of metal-on-metal binding in the forks and tiny bits of aluminum were constantly being deposited into the new SS-7M fluid. These tiny particles quickly made their way into the Showa’s delicate internals and gummed up the works at an alarming rate. As little as a few hours of use were enough to notice a dramatic change in performance and a complete disassembly and cleaning of the forks was the only way to improve their quickly deteriorating action.

|

|

Jeff Stanton had one hell of a year in 1990 aboard the new CR250R. He claimed both the 250 Supercross and Outdoor National titles, as well as helping to lead Team USA to a tenth straight Chamberlain Trophy at the Vimmerby, SwedenMotocross des Nations. Photo credit: Motocross Action |

In the rear, a new ratio for the Pro-Link was spec’d and mated to a revised Showa shock that aimed to smooth out the ’89 CR’s punishing ride. Much like the forks, however, the new settings were only a small improvement. The new shock came set up with a light spring, heavy compression damping and very light rebound. This made the bike good for slamming into one bump to clear another like Rick Johnson, but a bit of a handful at a more sedate pace. When ridden aggressively on a Supercross-style track, the Showa shock worked well, but on a choppy and snotty outdoor track, it was a hammering and hopping mess. Action was extremely harsh and the second you got tired and backed off, the rear was there to whack you in the tail and remind you to twist the loud handle back on. With a set of re-valves, the CR’s suspension could be made livable (not good mind you, just livable), but in stock condition it was by far the worse in the 1990 250 field.

|

|

Grim: In spite of Honda’s many changes for 1990, the CR’s 45mm Showa USD forks continued to be the weakest link in an otherwise excellent package. Undersprung, overdamped and incredibly harsh in action, these units continued to be the worst forks in motocross by a wide margin. |

|

|

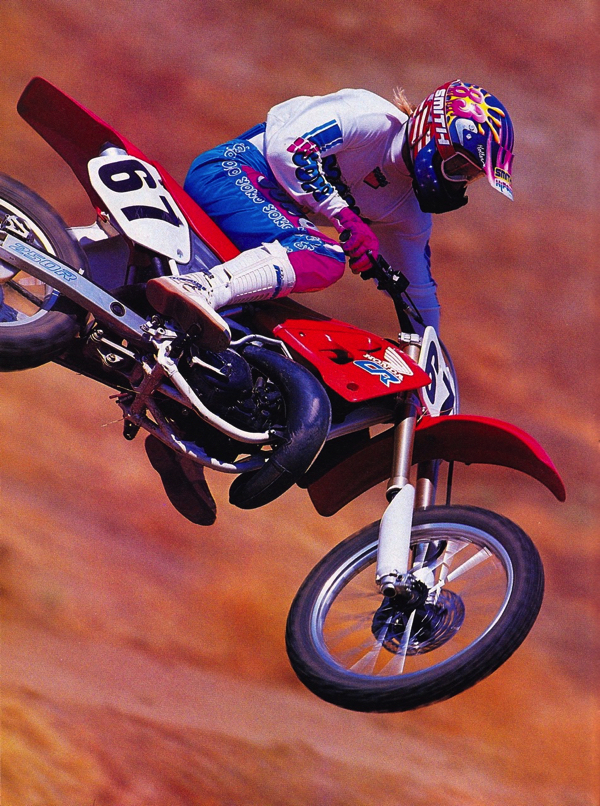

While the landings left a bit to be desired, the aerial manners on the new CR were impeccable. Photo credit: Dirt Rider |

While the suspension on the ‘90 CR continued to be a source of embarrassment for the proud manufacturer, nothing of the kind could be said about its award-winning motor. Originally introduced in 1986, the 249.3cc Honda Power Port (HPP) mill was unquestionably the best racing motor in the 250 class. Blessed with an explosive delivery and a nearly endless pull, this motor was faster stock than most manufacturers’ modified machines. In 1989, it offered a hard-hitting and long pulling brand of power that focused most of its thrust on the top end. Pro’s loved its burly blast and endless rev, but less skilled riders found it harder to manage.

|

|

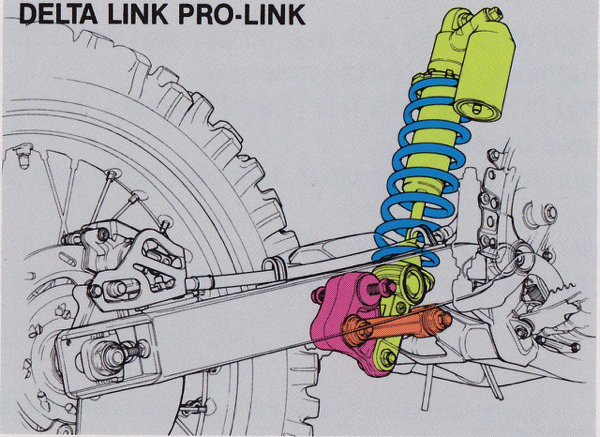

For 1990, Honda made some subtle changed to its Pro-Link rear suspension system in an effort to widen its appeal. Since the adoption of the Delta Link design in 1988, The CR’s Supercross focused rear suspension had been popular with pros, but loathed by those of lesser talent. |

For 1990, Honda looked to keep its amazing top-end pull, while at the same time smoothing out the 1989’s mid-range hit and beefing up its relatively soft low-end response. In order to accomplish this, Honda redesigned the reed valve, modified the cylinder’s porting (the exhaust port was lowered .5mm, while the transfers were raised .5mm), reshaped the HPP valves, lowered the compression (8.8:1 vs. 8.5:1) and reshaped the crank. In addition, a new airbox increased airflow and a new exhaust pipe (20mm shorter at the headpipe) and slightly shorter silencer (22mm) improved the excavation of spent gasses. Lastly, an additional drive and friction plate were added and new set of lighter rate springs were spec’d to improve the feel and durability of the Honda’s already excellent clutch.

|

|

Super Team: In 1990, Honda had Ricky Johnson, Jeff Stanton, Jean-Michele Bayle and Mike Kiedrowski all under the red banner. That is a total of 22 AMA and World Motocross titles on one team (not even counting the five World Motocross titles of team consultant Roger DeCoster). |

On the track, all those subtle improvements added up to one of the best stock 250 two-stroke motors of all time. Torque was way up over 1989 and the new orange CR pulled strongly from the first crack of the throttle. The midrange was still excellent, but the transition to the meat of the power was less abrupt due to the improved low-end response. Once past the burly midrange, the Honda just kept pulling and pulling into an eye watering top end hook. It was a nearly perfect motocross engine, blessed with both the most power and the easiest-to-ride powerband. Its only weaknesses were its slightly tall stock gearing (easily remedied), infuriatingly complicated HPP maintenance (and you think four-strokes are complicated) and an exceedingly annoying habit of fouling spark plugs (savvy riders ran a one-step hotter than stock plug and ALWAYS carried spares in 1990).

|

|

Old reliable: While it could be a handful at speed, the CR250R’s combination of light feel, aggressive cornering and flawless aerials manners made it one of the best handling packages in motocross for over a decade. Photo credit: Dirt Bike |

In the chassis department, the Honda engineers made several changes for the 1990 season. A new coat of white paint covered a frame that offered .2 degrees less rake and .1 inches more trail than 1989. The motor was also repositioned to sit 3.5mm higher in the chassis and the steering head was moved rearward 5mm and bumped up in diameter 30mm to increase strength. The footpegs were also raised 3 millimeters and widened by the same amount to increase rider comfort on hard hits.

|

|

This sano works-style chain guide was new for 1990. |

In spite of all of these changes, the CR retained the basic personality it had displayed since 1983. The CR’s cornering manners continued to be impeccable, with a sharp turn in and planted feel that communicated what the front tire was doing at all times. The new Suzuki RM250 gave the CR a run for its money in the turns, but its odd penchant for oversteer on exit and slightly hinged feel made it less confidence inspiring than the firmly planted Honda.

|

|

Mike Kiedrowski came into 1990 as the reigning 125 National Motocross Champion and a close runner up in the 125 East Coast Supercross series. In his first year on the big bikes, Mike carded five podiums and nailed fourth overall in the final series standings. Photo credit: Dirt Bike |

|

|

In 1989, several riders suffered wheel failures, so stronger hubs, thicker rims and beefed-up spokes were all on the agenda for 1990. In spite of the trend toward 19’ rear wheels at the time, Honda chose to stick with 18” rims on all the full-size CR’s. |

At speed, however, the Red Rooster continued to be the Coney Island Tilt-A-Whirl of motocross. Under power it was only mildly disconcerting, but once you rolled off the throttle, the CR developed a death wobble that was nasty enough to terrify Freddy Krueger. The oscillation was enough to rip your hands from the bars and pucker up your backside. Once the headshake started, there was no turning back and the only remedy was a say a prayer and hold on for dear life. Savvy Honda riders tightened down the steering head nut, worked on their bucking bronco skills and always remembered to pack clean shorts.

|

|

Hammer, or be hammered: Much like it had been in previous years, the rear of the new CR worked better for pros than amateurs. At quasar speed, its setup allowing fast guys to turn small humps into mega jumps, but for the more mortal among us, the harsh compression and light rebound damping made the CR a handful. |

In the details department the Honda was the class of the 1990 field. New bodywork gave the CR a smooth and seamless rider compartment and nothing got caught or interfered with a rider’s ability to go about his work. The new seat was loved by all, with a slightly taller profile for ‘90 and foam that did not sack out after three rides. Many riders liked the return to old Honda red (orange) color scheme, but just as many found the bike’s white frame a bit gaudy looking (if only they knew what was on the horizon). Both the brakes and overall controls were excellent and offered the best feel and most power in the class.

|

|

In 1990, Honda actually toyed with the idea of a fully automatic CR250R. Much like the Husky autos from a decade earlier, all a rider had to do was hit the gas and the bike did the rest. While the automatic RC250 reportedly showed a lot of potential, it never made it past the experimental stage. |

While the overall bike was the easiest to work on, with its works-style fully removable subframe, well thought out design and quality components, its exorbitant need for regular maintenance was daunting to many. The forks required disassembly three times as often as a typical machine in order to maintain consistent damping and the HPP valves would become badly gummed up if not tended to religiously. Worst of all, the HPP mechanism featured more springs, pulleys and gizmos than a do-it-yourself ejector seat kit and any anyone attempting to service them was wise to bring a manual and a good dose of patience. On the plus side, the bike itself was nearly indestructible, aside from a notch-prone clutch basket, mediocre DID rims and an nearly endless appetite for fresh spark plugs.

|

|

Play it again Sam: In 1990, Honda built a bike that pulled like a freight train, stopped on a dime and carved like a Ginsu. Of course, it also pummeled its pilots to a pulp in the rough. It was the same issue that had haunted CR owners the year before, and the same situation that would confront them for most of the next decade. The CR was a bike capable of winning at the highest levels, but it was left to the consumer to finish off what could have been an unbeatable package. |

In 1990, Honda rolled out two-thirds of the perfect motocross weapon. Nothing was as fast, smooth and easy-to-ride as the orange rocket. Unfortunately, nothing was as harsh, hammering or hard on the wrists. On a Supercross track, it was magic, but when you threw in the bumps and holes found on a typical motocross circuit, it became a handful. For a pro looking to make it big, there was no better choice, but for the rest of us mortals, the new Honda was a bit of a bittersweet confection.

Matthes: I had this bike and remember it quite well so I thought I’d weigh in here. I had ridden Kawasaki’s for the previous two years and this was the first time I rode red since my trusty ’87 CR 80. And I had never ridden a 250 so this was my introduction to bike bikes. In fact, my pops had gotten myself a loan for all three CR’s in ’90 so I owned and raced them all this year and the next. Anyways, the forks WERE way soft and the oil did get WAY dirty. I remember changing it all the time as well as putting stiffer springs on right away. Other than that, I left suspension stock (I put Race Tech Gold Valves in my 500 and they were great by the way).

Blaze is right, the HPP power valve system did suck and you had to have just the right amount of tension on the spring to make them work properly. Yes, I effed these up quite a bit. The ’92 system was a lot better. The motor was fantastic, I had a PC pipe and silencer on and that was it although my dad might have cleaned up the cylinder as was his wont to do. My 125 was full PC and it was fast, they did a great job. My old boss at Yamaha, Jimmy Perry, probably actually did the work for me…weird right?

One thing I have to take umbrage with in this column is the handling. I didn’t think it was that good to be honest. My buddy had an RM 250 and I remember it turning way better and still being stable. And I rode an ’89 CR 250 and thought it turned better than my ’90 also. But this was a long time ago, maybe I’m drunk.

The stickers were crap (the 500 had them embossed into the shroud and were brand new always…why in the hell would Honda just do that for one model one year? and the white frame looked like shit right away. Then again, I rode a ton and in the sand at that so my bikes did look hammered pretty quickly. I had gotten those trick TMV clutch and ignition covers that said “Honda Racing” on them which was pretty sweet and I put on a CEET non-slip cover that was red with grey anti-slip stuff on. I also had one of those front number plates that went down onto the fork tubes like the factory guys. It was made by TMV also.

Anyways, yeah bike was fast and the suspension wasn’t great. That was a theme for Honda’s for three or four years back then…but dat motor doe…

For your daily dose of classic motocross goodness, make sure to follow me @tonyblazier on Instagram and Twitter.