This week’s selection from Greg Primm’s Classic Steel is Honda’s first water-pumper, the 1981 CR250R.

The 1981 Honda CR250R Elsinore was a huge technological leap forward over the ’80 CR250R. With liquid cooling, Buck Rodgers bodywork and a Pro-Link rear end, Honda sold a lot of CRs in ‘81. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

It is hard to overstate the anticipation that accompanied the ’81 CR line at the time of its introduction. Compared to the machines that preceded them, the new CRs looked like something out of a sci-fi movie. The ’81 machines screamed performance from every angle, with the very latest in motocross technology. They were the most radical redesigns from Honda since the introduction of the very first CR250M in 1973. The new ’81 CRs promised works bike performance for the average man.

In terms of raw performance, the 246cc two-stroke was fast but hard to ride. The motor was boggy off the line, before pulling into a hard-hitting midrange blast. There was not a lot of power past the midrange, so shifting early was the most effective way to make competitive speed. While its explosive power made the bike fun to ride, it also made it tricky to race. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

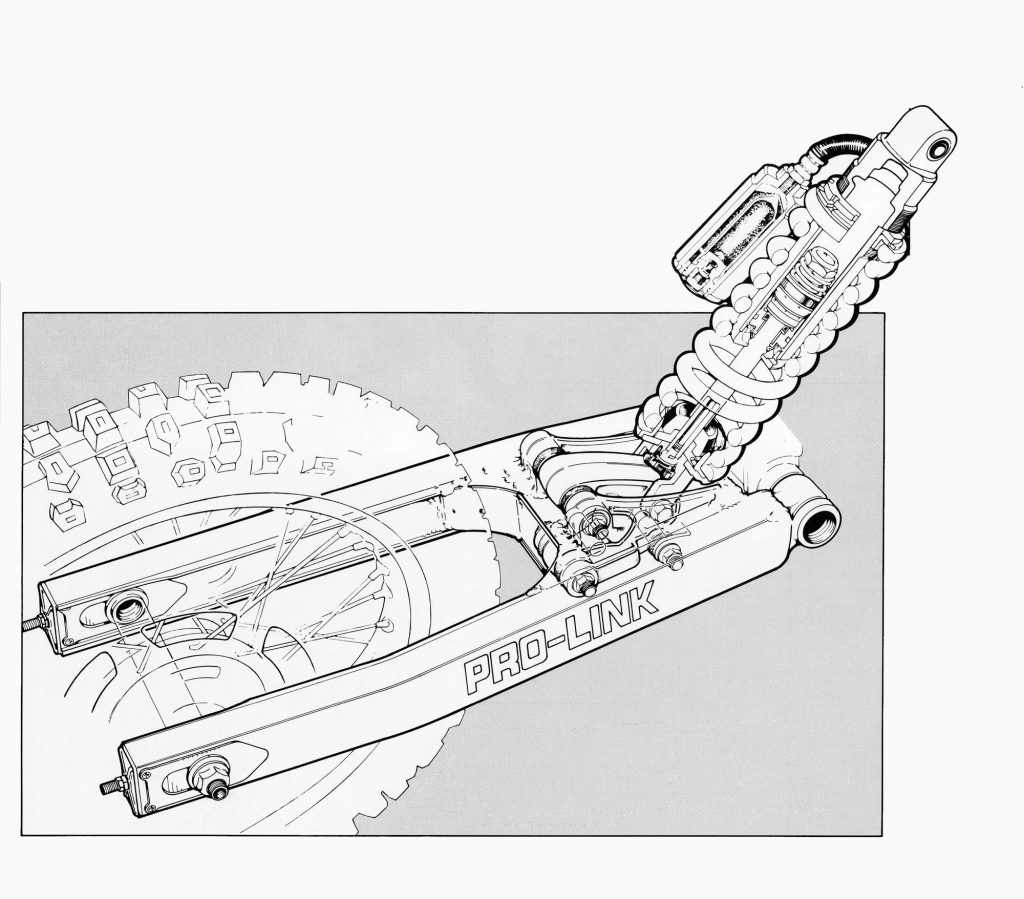

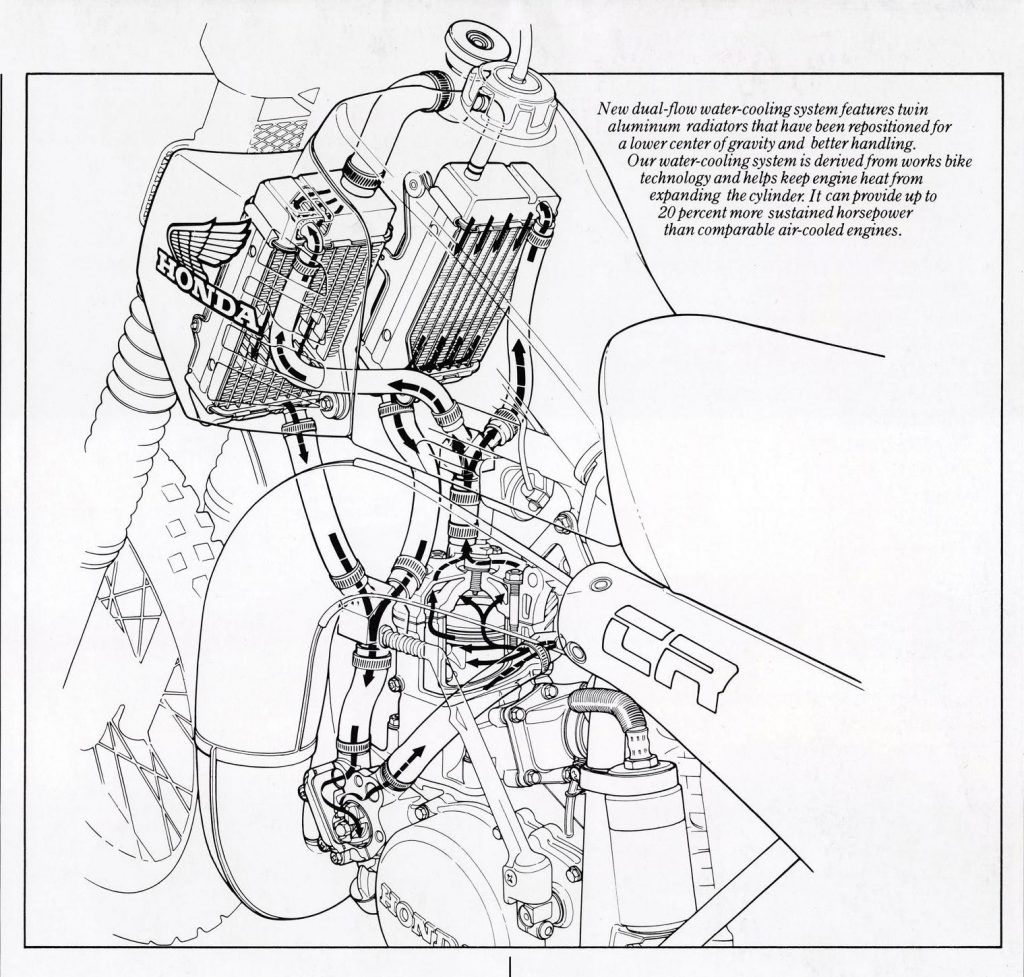

The all-new ’81 CR250R was a groundbreaking machine in many ways. The new chassis featured Honda’s first single-shock rear suspension system which they called “Pro-Link”. It consisted of a single Kayaba shock mounted to a set of rising-rate linkage arms. Another first on the ’81 CR was its new liquid-cooled motor. Honda was the first manufacturer to try liquid-cooling on its 250cc machine and it generated quite a stir at the time. Many pundits considered water-cooling a bit of overkill on a 250. Even if there was no real performance advantage at the time, it definitely gave Honda an edge in the showroom. Capping off all this whiz-bang technology was racy new bodywork and a screaming coat of red paint. With so much going for it, the new CR looked to be an unbeatable package in ’81.

In 1981, there were a lot of ideas out there about what made the best rear suspension design. All four Japanese manufacturers offered completely different configurations in search of the best combination of packaging and performance. Of all the original linkage suspension designs, only the Honda Pro-Link configuration has withstood the test of time. Photo Credit: Honda

The introduction of the Pro-Link rear suspension was big news for ’81. The switch did improve ergonomics, but in terms of actual performance, it was no better than some of the dual shock set-ups still on the market. When compared to Suzuki’s revolutionary new Full-Floater system, it was no contest. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In addition to the mediocre performance, the CR’s Pro-Link had reliability issues as well. The aluminum swingarm became notorious for cracking at the welds and the remore reservoir was well known for blowing off its hose. Honda quality still had a little ways to go in ’81. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In addition to the mediocre performance, the CR’s Pro-Link had reliability issues as well. The aluminum swingarm became notorious for cracking at the welds and the remore reservoir was well known for blowing off its hose. Honda quality still had a little ways to go in ’81. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The performance of the ’81 CR did not quite live up to the promise of its radical looks. The fire-engine-red motor produced a very difficult-to-ride spread of power. For starters, there was no low-end torque whatsoever. After the bike climbed past its lethargic bottom-end, you would be met with a sudden blast of midrange power, before it tapered off to a mediocre top-end pull. If you let the motor fall below the potent midrange, it would just go “wwhhaaaa” and bog down. The trick was to keep the engine in its narrow sweet spot. If you could do that it was competitively fast, but if you let it fall off the pipe, it would take an eternity to climb back on. The anemic low-end meant the rider was forced to use a lot of clutch out of corners, unfortunately, the stock clutch was not up to the abuse. It would chatter and grab badly when hot, then finally give up the ghost completely if hammered. The five speed transmission worked well when in one piece, but broken gears were a common occurrence. Third gear, in particular, had a bad habit of grenading at the most inopportune moments.

Reliability issues plagued the new CR’s motor. When new, the clutch grabbed, dragged and chattered. If pressed, it began slipping and became utterly useless in short order. The transmission was also incredibly fragile and broken gears were common. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrande

The one thing that worked as promised was the liquid cooling. Honda used a much simpler approach to their cooling system than Yamaha had done with their new liquid-cooled YZ125. Unlike the YZ, which mounted the radiator on the steering head and piped coolant through the frame, the CR mounted its dual radiators at the front of the gas tank and piped the hoses directly to the engine. The radiators were still mounted fairly high on the bike but the Honda design was far less complicated and less prone to leaks. As long as you checked the coolant level regularly, it was pretty trouble free.

This is surely the most infamous front numberplate in history. The goofy looking monstrosity was designed to direct more air to the high mounted twin radiators. European and other markets received a much less ridiculous version than the hangnail the US got. There were a lot of aftermarket numberplates sold to CR owners in ’81. Photo Credit Stephan LeGrand

The actual performance of the Pro-Link was decent, but not spectacular. Initially, the action was very plush, but the transition the shock made as the rising rate kicked in was too sudden. It was harsh in the mid-stroke and would kick if the power were not kept on. The shock itself was prone to fading and offered very little adjustment. There was no compression adjustment at all and only four selectable rebound settings. Overall, it was a decent first attempt in need of a little fine-tuning.

The new Pro-Link rear offered a remote reservoir to aid cooling, but not external compression adjustments. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

After nearly a decade of terrible forks, Honda went with the bold decision to switch to Kayaba suspension on the all-new CR. Amazingly, the 41mm Kayabas performed no better than the awful Showas had (this in spite of the fact that the same Kayaba forks performed brilliantly on ’81 RM). The set up was all wrong, with overly soft springs and harsh damping. Dirt Bike Magazine likened their performance to a set of pogo sticks. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The forks on the CR were 41mm (considered very large at the time) Kayaba units. This was another big change for Honda; up to this point CRs had only used Showa components (Honda owned a huge portion of Showa at the time). At this time Showa had a pretty poor reputation as far as forks go, so the switch to Kayaba was met with optimism. As it turned out, the Kayaba’s performed just as bad as the Showa’s had before (Since Honda was the one setting the forks up, and they seemed to work just fine on the yellow brands, it must have actually been them that were messing things up). They were way too soft initially,then would virtually hydraulic lock in the mid-stroke. The rebound was so light that the front wheel would nearly try to bounce back off the ground when landing from jumps. Adding air or oil to the forks only magnified the harsh action. These were a hopeless set of forks.

The 1981 CR line would be the last models to wear the legendary Elsinore name. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The all-new ’81 CR250R certainly looked impressive on the spec sheet. Photo Credit : Honda

Handling wise, the CR250R Elsinore was a mixed bag. The main problem was the bike’s weight, which teetered near 250 pounds. That actually made the ’81 CR250R heavier than most ’81 Open class bikes. The combination of the liquid cooling, beefy rear suspension and a complete lack of lightweight components drove the new CR right into XR250 territory. Exacerbating the heavy feel were its highly placed radiators and tall gas tank, which put a lot of that weight up high. On the plus side, the bike actually turned decently, with a tightly-planted feel in corners. Where the weight worked against you was off jumps and in quick transitions, there the CR felt more like a big 500 than a nimble 250.

Honda’s new liquid-cooling solution was simpler than Yamaha’s steering-head-mounted system, but it still placed the radiators too high up on the chassis for optimal weight distribution. Photo Credit: Honda

Detailing on the CR was excellent, with superb quality castings and high quality plastic. Everything on the bodywork fit perfectly and was extremely durable (including the ridiculous front number plate most people probably wished had fallen off). Brakes were a real highlight with a super powerful (for the time) dual leading shoe setup that MXA even said was overkill (I know, crazy huh?). The rear was excellent as well, with good stopping power and excellent feel.

This was the best brake in motocross in 1981. The dual leading shoe design used a set of linkages to push the shoes apart from both sides. This was a major advance over the single action drum brakes common up to this point. The reign of the dual-leading shoe would be short-lived, as discs would supplant them within a few years.

Much like the motor, reliability was a real issue with the chassis. Frame breakage was a huge problem on the ’81 CRs. MXA and Dirt Bike broke the frames on both of their test bikes with MXA’s actually snapping in half. There was also a major problem with cracked swingarms and blown shocks. Air filters were also known to leak badly at the seal and many a CR ground itself to a halt from sucked debris. Clearly, there were still a few kinks to be worked out with this design.

At close to 250 pounds, the CR250R actually outweighed several Open class bikes in 1981. The porky weight certainly did the bike no favors in the acceleration and handling categories. With its lackluster performance and abysmal reliability, the ’81 CR250R is remembered as one of Honda’s worst ever production bikes. Photo Credit: Stephan Legrand

In the end, the high-tech CR was felled by the most basic of problems. You could port the motor and re-valve the suspension, but if the bike would not stay in one piece there was little point. Motocross is an incredibly demanding sport and the ’81 CR250R was just not up to the task. Like a fighter with a glass jaw, it was always one hard hit away from going down for the count. Whether it was the fragile motor or the brittle frame, there was always a problem waiting in the wings for the unsuspecting CR owner. The ’81 CR250R was a bike of big ideas, spoiled by poor execution.