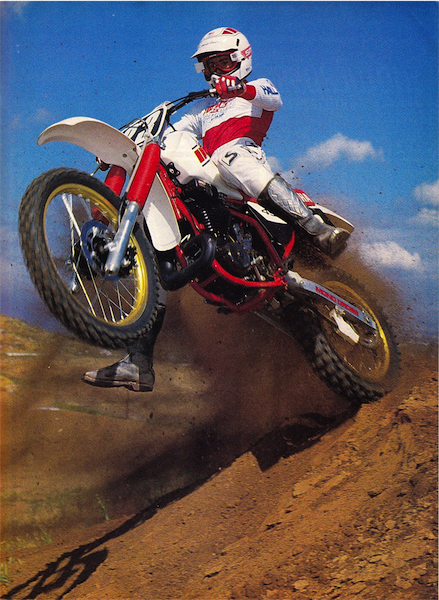

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the machine that took Broc Glover to his last 500 National Motocross title, the 1985 Yamaha YZ490.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the machine that took Broc Glover to his last 500 National Motocross title, the 1985 Yamaha YZ490.

|

|

In 1985, the Open class was still considered one of the most prestigious divisions in motocross. Honda, Kawasaki, Husqvarna, KTM and even Cagiva, all produced liquid-cooled big-bore beasts for consumers. Of all the bikes in the 500 class, only Yamaha remained air-cooled for ’85 (Suzuki did produced an air-cooled RM500, but did not import it to the US after 1984).

|

The eighties were a period of transition for the Open class in motocross. At the start of the decade, big-bore machines were still considered the pinnacle of the sport. The trickest works bikes were often to be found in the 500 class, and the biggest stars aspired to race the massively overpowered beasts. As the decade went on, however, interest in the Open bikes began to wane. In America in particular, our love of the 125 and 250 classes started to lessen the influence of the big-bores. Americans voted with their wallets, and voted strongly for the easier-to-ride small-bore machines.

|

|

While the air-cooled mill on the YZ490 may have been old-fashioned, it was not lacking for power. Twisting the loud handle on the YZed was still paramount to setting off a Roman candle between your legs.

|

As sales of the big-bores machines fell off, it started to become less cost-effective for the manufacturers to invest in costly redesigns of their 500-class machines. In 1984, Suzuki pulled the plug on their moldy RM500, abandoning the class altogether (at least in America, it continued to be available for one more year in other markets). This left Honda, Kawasaki and Yamaha as the last Japanese holdouts in the class.

|

|

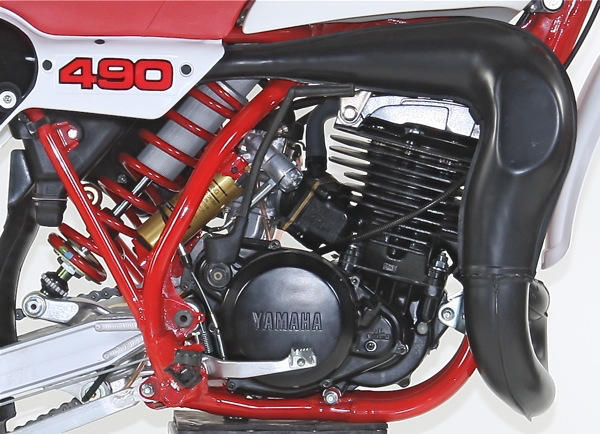

For 1985, the Yamaha’s 487cc mill remained largely unchanged from the year before. While it was as powerful as anything in the class, its spotty jetting and widely spaced four-speed trans handicapped its performance.

|

While Suzuki failed to see the benefit to continuing in the class in 1985, Honda and Kawasaki plowed ahead at full steam. Both the green and red machines were all-new for ’85, with liquid-cooling making its debut for the first time in Japanese 500 class. While originally thought to be unnecessary on a big-bore, the addition of liquid-cooling proved to be a great aid in getting the notoriously finicky machines to carburet and run cleanly. The big 500’s still made do without the power-valves found on their smaller cousins (and the works 500’s), but the addition of the water-cooling went a long way toward making these overpowered beasts more livable.

|

|

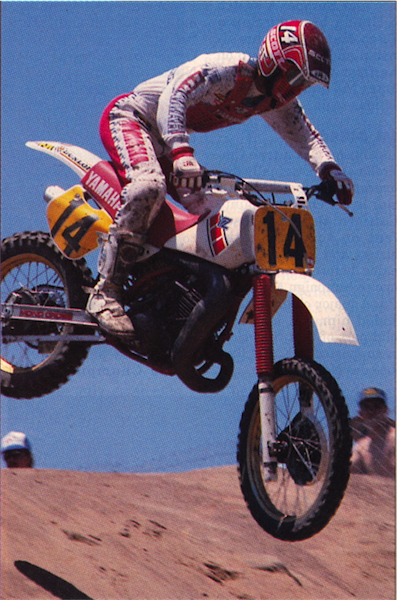

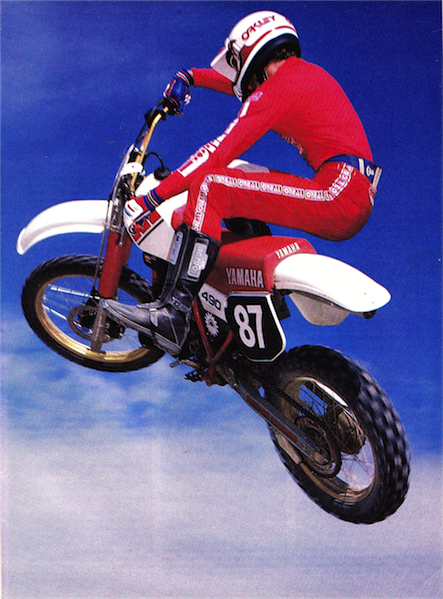

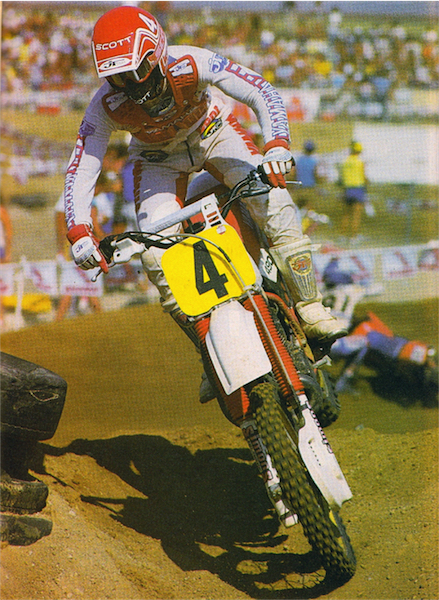

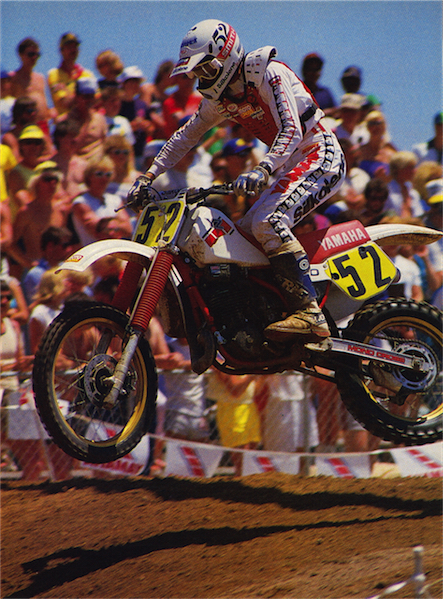

In 1984, Yamaha decided to forgo their costly “works bike” program and instead, race production-based machines. In spite of this disadvantage, both Broc Glover (pictured above, on his production based YZ490 at the 1985 500 USGP) and Ricky Johnson remained very competitive against their works-mounted rivals.

|

As for Yamaha, by 1984 the manufacturer was feeling the pinch of an economic downturn and the loss in sales that comes from sub-par products. After a solid run to end the decade, Yamaha had fallen on hard times in the early 1980’s. The once powerful brand was cranking out poor products that failed to connect with consumers. The YZ125 was the laughingstock of the class and the new-liquid cooled YZ250 had failed to impress. The one holdout to this mediocrity had turned out to be Yamaha’s big-bore YZ. The YZ465 had become an all-time classic and the follow up YZ490, while not as good, was a solid contender. The air-cooled Yammer pumped out ponies to spare and still enjoyed a loyal 500 following.

|

|

Unobtanium: In 1985, the discrepancy between the haves and have-nots of motocross could not have been starker. Bikes like this Factory Honda RC500 of Ronnie Lechien employed not a single part off the production line and cost upwards of ten times that of Broc Glover’s Yamaha.

|

|

|

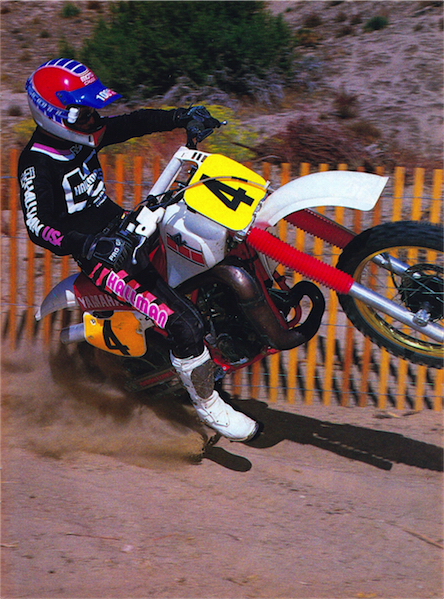

Slumming: In 1985, the bike Broc used to win the 500 National motocross title actually differed very little from the production YZ490. Probably the most exotic part was the works five-speed trans, which helped narrow the wide gaps in the stock bike’s four-speed transmission. Along with the trans, Glover’s mechanic Jon Rosenthal ported the cylinder and reshaped the head to smooth the power and clean up the jetting, mounted an ‘84 works pipe mated to a shortened stock silencer and drilled the airbox for better flow. The ignition, carburetor and reeds remained stock. Up front, the stock 43mm KYB’s were retained, but the internals were swapped out for a works version of Simons’ anti-cavitation kit. In the rear, Jon R. ash-canned the stock BASS-o-matic shock for a trick Öhlins unit.

|

In 1984, none of the big four had produced much of a winner in the 500 class. Kawasaki, in fact, had failed to even offer a 500 for ’84, after the dismal failure of their grenade-prone ’83 KX500. For ’84, Honda introduced a highly anticipated follow-up to their world-beating ’83 CR480R, which ended up scaring more people than a Friday the 13th triple feature. It pinged, it rattled and it tried to swat off its rider at every opportunity. The 1984 CR500R was the very embodiment of everything that scared people away from 500-class machines.

|

|

Massaged: When Moto Cross magazine tested Broc’s Factory YZ490 at the end of the ’85 season, they came away impressed with how much of a difference carful detailing and a few select modifications made to the stock YZ. By far the biggest improvements were the addition of the five-speed transmission and the aftermarket suspension, which addressed both of the stock bike’s biggest shortcomings.

|

Suzuki’s entry in 1984 was far kinder and gentler than the rocket sled Honda, but no more competitive. The ‘84 RM500 was basically a 1981 RM465 with a new coat of blue paint and some bold new graphics. At this point, it was a generation or three behind the other bikes in the class, and in sore need of a makeover that would never come. It was mellow and easy to ride, with the best suspension in the class, but too slow to be a contender. This left the Yamaha with the best combination of horsepower, handling and overall competence as the top 500 of ’84. It was slightly porky, poorly jetted and grim-forked, but it did the best job of going fast, while not killing its pilot.

|

|

Confused: While the power was plentiful for ’85, using it was another matter. In stock condition, the 490 was a sputtering and pinging mess. If you attempted to lean out the jetting to crispen the response, then the bike tried to grenade itself when hot. If you jetted it so it would not rattle itself to death, the bike was blubbery and unresponsive. Even worse, 90% of the YZ’s power was situated on the top-end, where most Open bikes fear to tread. For most riders, the pinging and mind numbing vibration were reasons enough to back off the throttle long before the big 490 hit the peak of its unorthodox power curve.

|

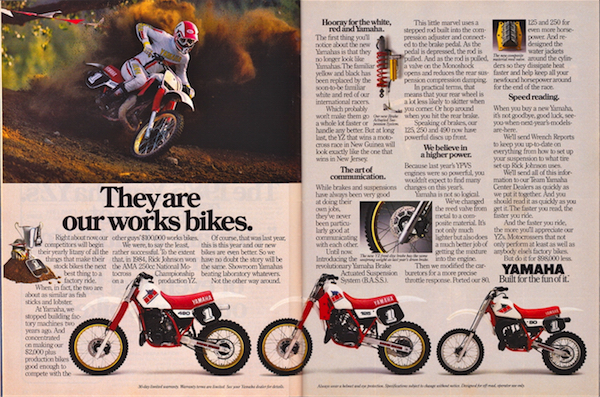

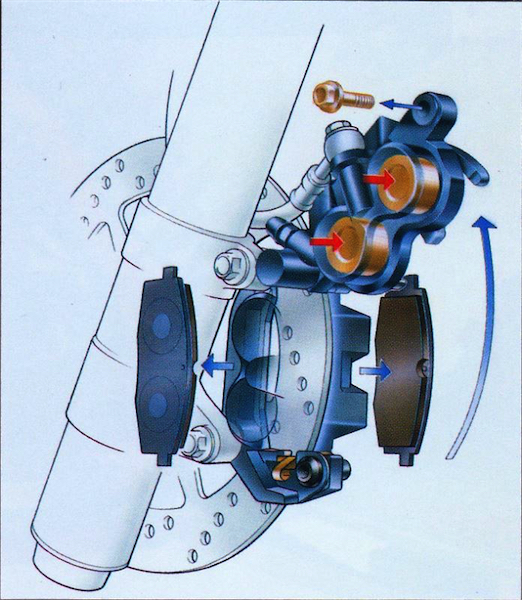

For 1985, Yamaha more or less stood pat with the machine that won the class in 1984. Visually, a new coat of white and red paint brought the YZ in line with its international brethren and helped the bike look newer that it actually was. The frame was unchanged, save the new red paint, and most of the bodywork was retained from ’84. A new slightly flatter saddle helped address complaints that the ’84 was hard to move around on, but the bulbous 2.8 gallon tank remained. Aside from the BNG, the biggest changes for ’85 were the addition of a disc brake to the front, a set of revised Kayaba forks and a new-fangled gizmo for the shock Yamaha branded BASS.

|

|

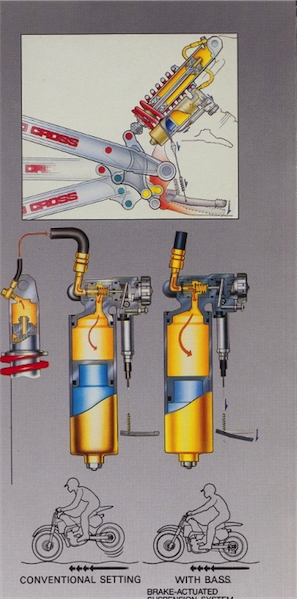

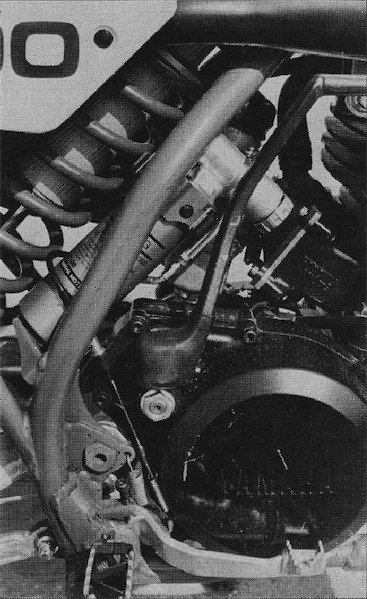

While 90% of the YZ490 was a carryover from the year before, there were some significant changes for 1985. Probably the most high profile of which, was the Yamaha’s new BASS equipped shock. The BASS (Brake Actuated Suspension System) was invented to provide better rear suspension response while braking in the rough. The BASS used a cable connecting the rear shock to the rear brake lever to bleed off 10% of the shock compression damping force when the rear brake was applied. By lowering the compression damping in these situations, it was thought that the shock could more acutely respond to the small, sharp bumps common to corner entrances in motocross.

|

While the motor on the Yamaha was a low-tech design basically dating back to the seventies, it was actually not much of a hindrance against its liquid-cooled rivals. In terms of outright power, the 82mm x 83mm 487cc monster put out as much power as anything available in 1985. Where it lost out, however, was in the delivery of that power. Off the showroom floor, the 490 was a blubbering, pinging mess. Low-end was virtually non-existent by 500 standards and the bike actually preferred to be ridden like a 250, instead of the typical tractor 500. Once past the erratic low-end, the mighty 490 lit the afterburners and pulled to the moon with a ferocious delivery of ponies. It was like a 60 horsepower 125 with a bad case of the pings. On top, the 490 had no peers and it would pull far past the point where the other 500’s had given up the ghost. In terms of outright acceleration, the YZ was faster, if given enough room, but far less quick from corner to corner.

|

|

Brace for impact: Unless you were looking to remove a few fillings, highflying maneuvers were ill advised with the YZ490’s grim stock suspension.

|

Exacerbating the odd-for-a-500 powerband, was the machine’s four-speed trans, which both limited its versatility and magnified its poor low-end performance. With the stock gearing, the transmission was slightly gappy and virtually always in the wrong gear. Amazingly for a 500, the big YZ would actually fall off the pipe between shifts if not properly revved out. Even worse, just cranking on the throttle was not enough to get the big Yammer going again, as it was more likely to load up if treated like a typical big-bore tractor. Better to abuse the clutch and blow out the cobwebs if you needed a burst of ponies in a hurry. Vibration was also a major problem, as the air-cooled 490 was notorious for rattling its pilots to death.

|

|

Yamaha’s 1985 ads proudly proclaimed that their team actually raced what they sold on the showroom floor.

|

|

|

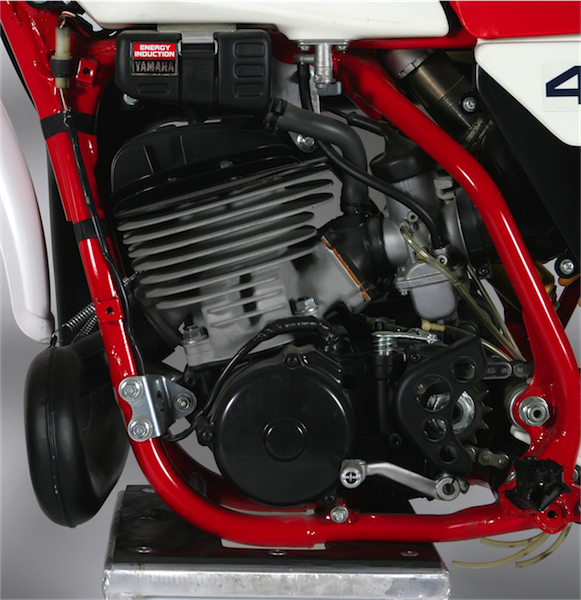

Boosted: In 1981, Yamaha introduced the Yamaha Energy Induction System (YIES) to the YZ line. Common on factory bikes going back to the mid-seventies, the YIES (or “boost bottle” as it was more commonly known) was a small chamber bolted to the intake manifold that was designed to provide a still air charge to the motor when needed. Yamaha was the only manufacturer to add a boost bottle to the production bikes, but many aftermarket companies offered them as an accessory. They would fall out of favor by the middle part of the decade.

|

So where did this leave the unsuspecting YZ490 pilot in ’85? If you tried to ride the YZ like it preferred to be ridden, you were going to wear yourself out in short order. The explosive delivery and mind-numbing vibration were a recipe for exhaustion if you pinned it like a 125, but the blubbery jetting and lackluster low-end made tractoring it around like a typical 500 ineffective. If you were smart, you took the beast to a savvy tuner like Al Holley (father of Factory Yamaha rider Jim “Hollywood” Holley) who could rework the head to cure the constant pinging and finally get the jetting sorted. With a head mod done and carburation sorted, the big 490 became a potent weapon for motocross, but its four-speed remained a handicap for anything else.

|

|

While the deletion of radiators gave the YZ a slightly less porky profile than the new water-cooled Honda CR500R, its steeply rising tank and scooped out riding position made moving around on the 490 a laborious endeavor.

|

|

|

In spite of steep competition and a far inferior bike, Yamaha’s Broc Glover took his production-based YZ490 to the 1985 500 National Motocross title.

|

In the chassis department, the YZ remained the same solid handler it had been the year before. Steering was sharp for a big and powerful machine and the bike cornered well in spite of a bulbous tank that rose too steeply and made weighting the front end difficult. At speed, the 490 could be a handful, but that was more due to the suspension than the chassis geometry. Put frankly, as long as the track was smooth, the YZ was up to the task: throw in some bumps, however, and things got ugly in a hurry.

|

|

In 1985, David Bailey looked like a shoe-in to capture a second consecutive 500 National Motocross title. Unfortunately, bike problems and nagging injuries would conspire to prevent the Little Professor from making it two-in-a-row in 1985.

|

First on the list of culprits were the Yamaha’s new 43mm Kayaba forks. These damper-rod beauties offered adjustable compression damping and 11.8 inches of wrist pounding travel. In stock form, they were too soft for anything resembling motocross and would bottom out on anything bigger than a gum wrapper. Damping was equally grim, with a nasty spike in the mid-stroke and enough rebound to bounce the front tire back in your face on hard landings. In 1985, the hot setup was to swap in stiffer springs and install a Simons Anti-Cavitation kit to smooth out the damping. Basically, this was the only way to make the stock forks even remotely rideable.

|

|

The stock forks on the 1985 YZ490 were virtually useless in stock condition. Badly undersprung and overdamped, they bottomed out on anything larger than a speed bump and hydraulic locked in the mid-stroke. With a set of stiffer springs and a Simons Anti-Cavitation kit, the forks went from terrible to livable.

|

|

|

Gas and plastic don’t mix: Yamaha’s stock decals were good for about .25 hours of riding abuse.

|

Unfortunately for the Yamaha faithful, things were no more optimistic out back. For 1985, Yamaha spec’d a new shock for the YZ490 that was supposed to offer greatly improved action in the rough. The big news about this shock was the incorporation of Yamaha’s new Brake Actuated Suspension System (BASS), which was designed to smooth the suspension’s action under braking. The BASS used a cable connected to rear brake, which then ran to the shock’s reservoir body. When the rider stepped on the rear brake, this cable would pull a bleed valve in the shock, which lessened the compression damping force by 10%. In theory, this would allow smoother performance under braking by letting the shock to more closely follow the terrain.

|

|

Undersprung and underdamped, the rear shock on the YZ was a real handful in rough terrain. Big jumps resulted in a mighty thud and sharp whoops sent the rear end skyward in a side-to-side pirouette of death. If you were serious about racing the 490, an aftermarket shock was a must.

|

In practice, the BASS turned out to be a clever, but ineffective gimmick. On the track, the YZ’s shock was a hopping and hammering mess. Big hits would easily bottom the shock and repeated whoops would send the big YZed into a terrifying side-to-side swap. Rebound was virtually nonexistent and the rear tire was known to launch skyward on high-speed impacts. The BASS did little to aid the shock’s performance and actually hindered it by allowing the unit to blow through its travel if the brake was accidentally applied on hard hits. Many riders just disconnected it altogether to little or no adverse effect. As with the forks, the aftermarket was the hot setup and most serious riders (including Team Yamaha) ponied up the money for a quality aftermarket unit from a manufacturer like Öhlins.

|

|

Rube Goldberg: While the BASS sounded like a promising idea, its effectiveness on the track was dubious at best. The BASS did little to calm the YZ’s poorly damped shock and could easily cause the unit to bottom off jumps or whoops if engaged inadvertently. Even worse, the system required careful setup and vigilant watchfulness to assure proper operation. In the end, many riders disconnected it altogether.

|

In the detailing department, the Yamaha was pretty middle-of-the-pack for 1985. The ergonomics were pudgy (while not quite as bad as the absurdly portly Honda) and the steeply rising tank was always in the way. Most riders found the new taller seat a big improvement, but the YZ remained the most “sit-in” bike of the 500 class. While the air-cooled YZ was actually the lightest of the three Japanese 500’s, its husky-sized bodywork and old school ergos made it feel the heaviest on the track.

|

|

Pucker Power: While the introduction of a 240mm dual-piston front disc was a welcome addition for ’85, most riders found it only slightly better than the ’84 YZ’s excellent dual-leading shoe front binder.

|

The new brake disc brake was an improvement, but not light years better than the excellent dual-leading shoe binder used in ’84. Shifting remained a hit-or-miss affair, with a heavy boot needed to assure the next gear was properly selected. Even if you could get the next gear selected, chances were you needed a different one. Lowering the gearing helped the gappy trans, but then the bike had less top speed than a CR80R. Unfortunately, the five-speed would have to wait one more year for the 1986 redesign.

|

|

With an upgrade to the suspension and a little motor work (to cure the pinging and jetting issues, not necessarily for more power) the 1985 YZ490 became a potent motocross weapon capable of competing at the highest levels. Here, National pro and Moto Cross Editor Ed Arnett puts the mighty 490 through its paces at the 1985 Las Vegas 500 National

|

.

|

|

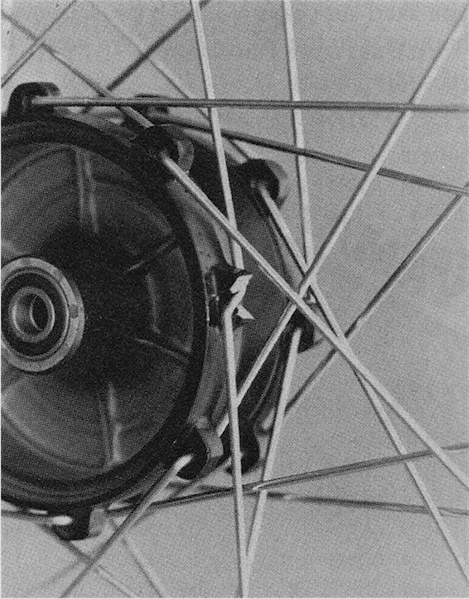

The infamous Z-Spokes were beefed up, but back for another year of cracked hubs in ‘85. 1986 would bring with it an all-new wheel and an end to the troublesome design.

|

New rims were stronger that the butter-soft items used in 1984, but the problematic Z-Spoke wheel remained to torment riders another year. While the 490 pinged mercilessly and was virtually impossible to jet properly in stock condition, it actually proved pretty reliable overall. Its biggest nuisance was its relentless vibration, which tended to loosen motor mounts and pretty much anything attached with a nut. If left unattended, this would lead to cracked motor mounts in short order. The lack of a radiator simplified rebuilds and it was one less thing to bash in a tip-over. Shock adjustment was also the easiest of all the 500’s, with both the compression and rebound adjustments easily accessible.

|

|

In 1985, the Yamaha YZ490 still offered the raw horsepower to win races, but mated it to a package lacking in refinement and suspension finesse. It was a rattling, vibrating, brute of a machine that pounded its rider to pulp at every opportunity. With work it could be a winner, but out of the crate, it was a handful.

|

In 1985, the Yamaha YZ490 remained the last holdout from the simpler days of motocross. There was no fancy exhaust gizmo, case-reed induction or zoot-capri water-cooling, just a big piston and lots of displacement. Amazingly, this did not truly handicap the YZ against its more modern rivals. The old girl still had plenty enough power to dislocate shoulders and rearrange landscapes. In the case of the YZ, it was actually its most up-to-date components that let it down. Its high-tech shock and beefy forks were the worst components in a class littered with poor performers. On a 125, this may have been overlooked, but on a 60 horsepower brute, it was paramount to vehicular homicide. Still, the old girl was a solid base, and with the simple addition of a fork kit, shock and head mod, it truly was capable of winning on the national stage.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier