For with week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to step into the Wayback Machine to take a look at one of the most infamous machines of the 1970’s, the 1977 Can-Am MX-3 “Black Widow”.

For with week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to step into the Wayback Machine to take a look at one of the most infamous machines of the 1970’s, the 1977 Can-Am MX-3 “Black Widow”.

|

|

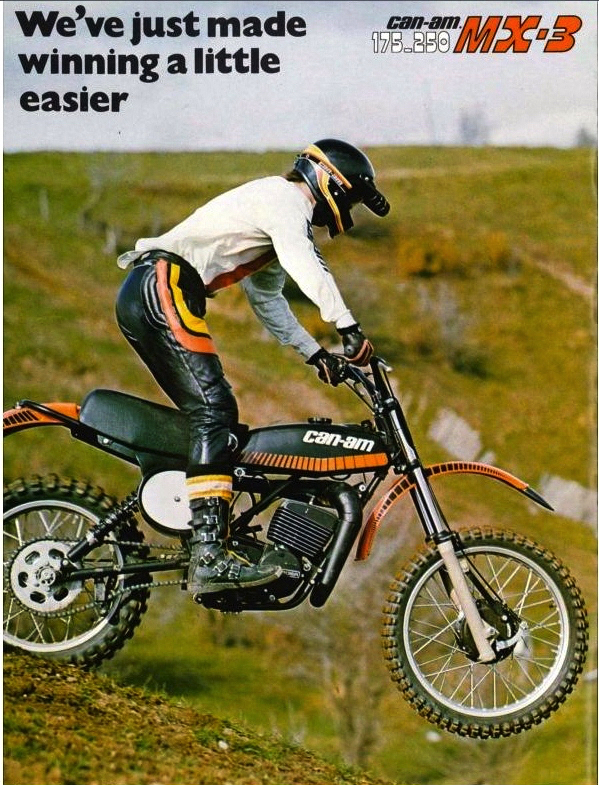

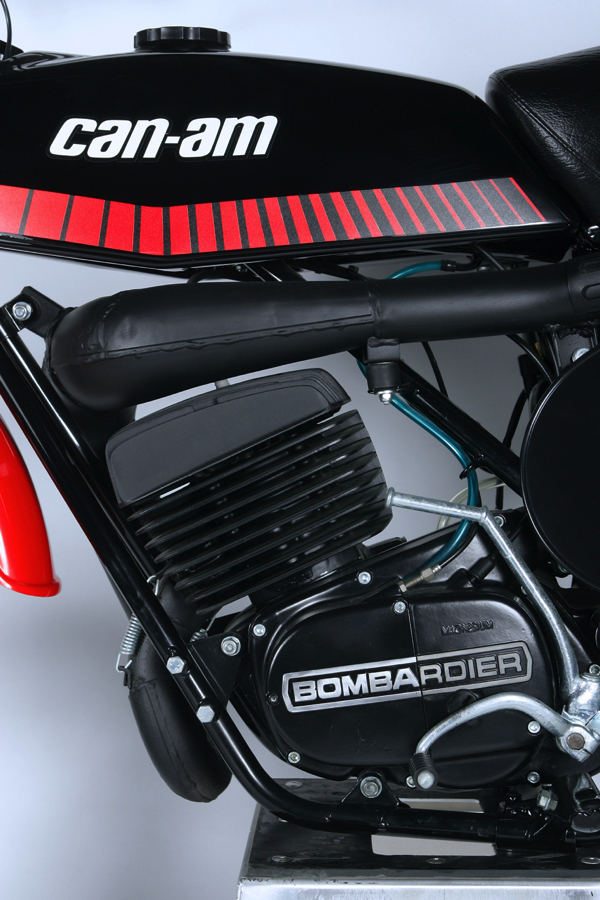

In 1977, Can-Am unleashed this black and orange beauty on the unsuspecting motocross community. Quickly dubbed the “Black Widow”, for its unique color scheme and penchant for attempting to kill its pilot, the MX-3 remains an icon of seventies motocross futility. |

Today, Can-Am is best known as a purveyor of ATV’s and side-by-side UTV’s (and the occasional odd-ball three-wheeler). Once a motocross power, this subsidiary of Canadian manufacturing giant Bombardier has been reborn in the new millennium. By shedding the baggage of years of neglect and poor designs, Bombardier Recreational Products (BRP) has been able to take a name that faded away to an ignominious end in the mid-eighties and resurrect it as premium brand for discerning off-road enthusiasts.

|

|

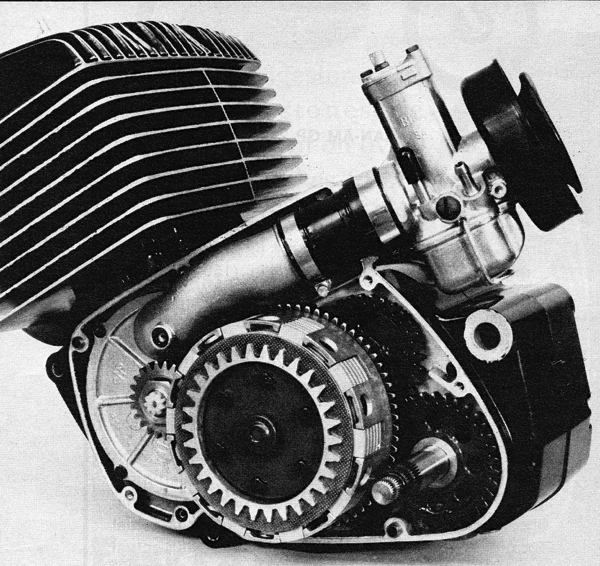

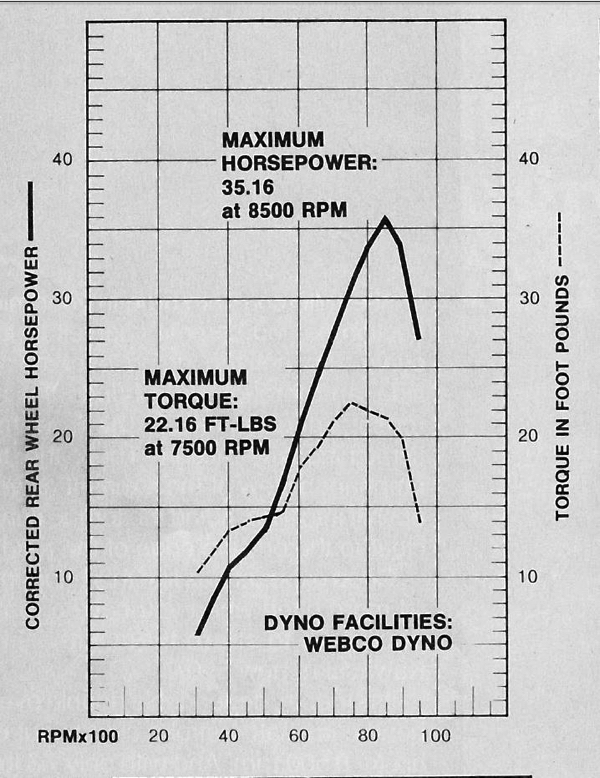

In the seventies, Can-Am’s were the fastest machines in the motocross business. Using a unique rotary-valve intake, these Rotax built two-stroke singles ripped through the powerband and revved to the moon. |

In the early seventies, the motocross market was awash in manufactures trying to get their cut of the exploding off-road market. Traditional powers like CZ, Maico and Husqvarna were still the cream of the crop, but they were soon to come under fire from Japanese upstarts like Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha. In 1973, you could choose from any of a dozen machines to ride from manufacturers all over the globe. England, Spain, Germany, Sweden, Austria, Japan and even the US, made bikes capable winning motocross events and claiming the consumer’s hard earned dollars.

|

|

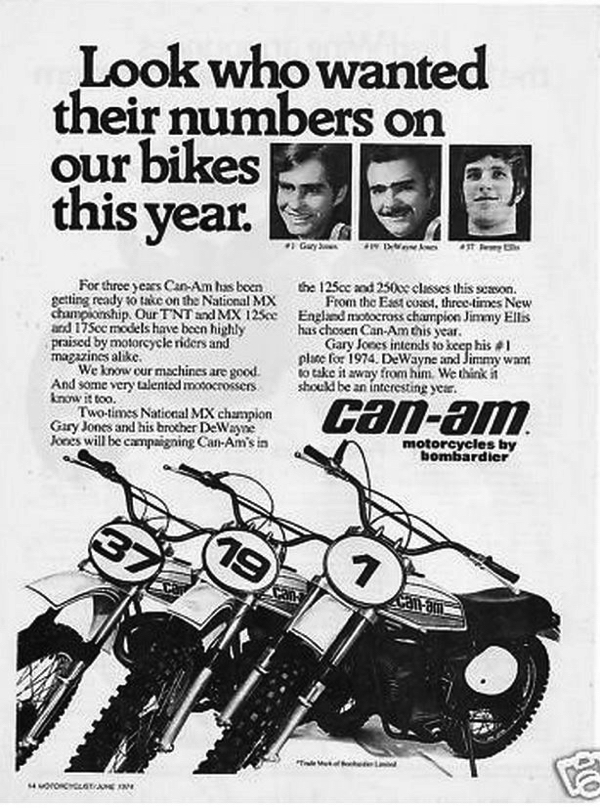

In 1974, Can-Am swept the top three positions in the 250 National Motocross standings. This was an incredible accomplishment for a completely unproven brand in its first year on the circuit. |

|

|

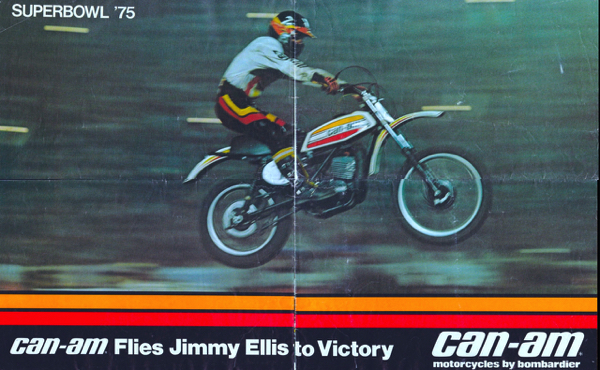

In 1975, Can-Am backed up their ’74 motocross success with the 1975 Supercross title care of factory rider Jimmy Ellis. |

In the early seventies, Bombardier took a hard look at this burgeoning market and decided to throw their hat in the ring of off-road motorcycling. Long a power in the snowmobile industry, BRP was no stranger to the off-road enthusiast market. In 1937, Bombardier had created the world’s first snowmobile with the B7, and by 1970, owned 90% of the global snowmobile market. In North America alone, BRP had 4000 dealers ready and waiting for a product to fill out the lean summer months when Ski-Doo sales tapered off. With a dealer network in place and the promise of big profits in the offing, Bombardier set about creating a new motorcycle company.

|

|

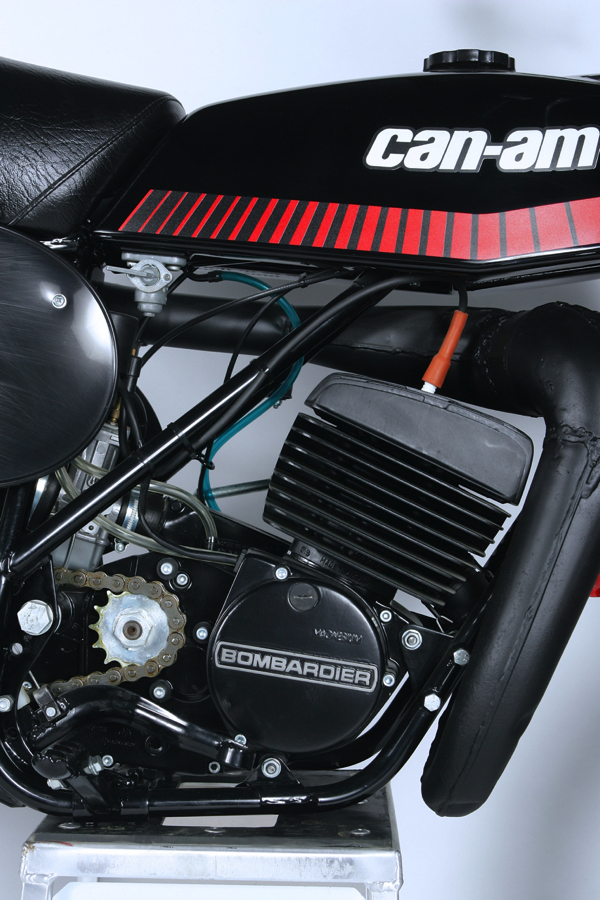

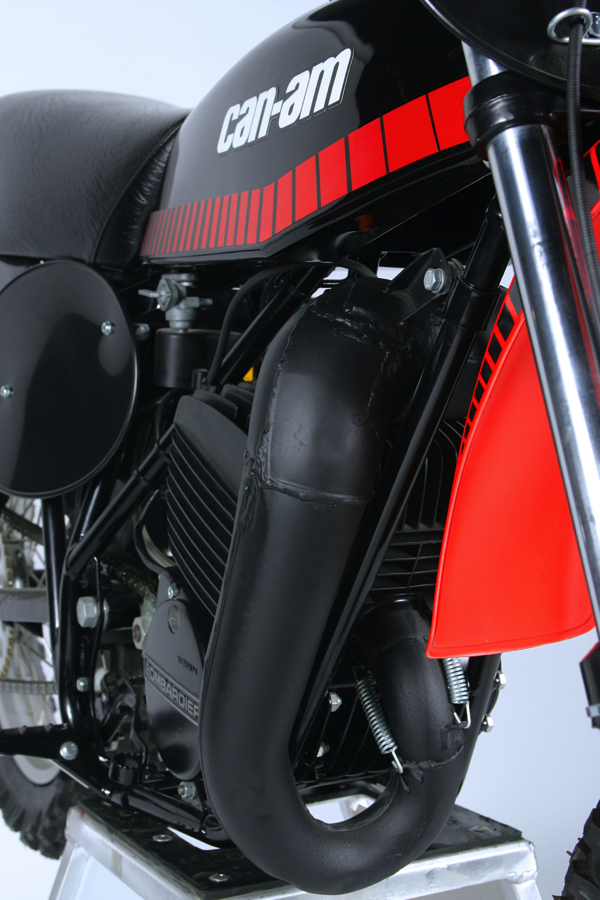

The 74 x 57.5mm, 247cc rotary-valve single used in the MX-3 belted out a massive jolt of forward thrust for its time. Power was hard-hitting , with a light-flywheeled delivery. While the Can-Am was by far the fastest bike in the 250 class, it could be a handful for less experienced pilots. |

After the decision was made to move forward with the motorcycle project, Bombardier enlisted the talents of American engineer Gary Robinson and two-time 500 World Motocross champion Jeff Smith to help develop their new motorcycle. Dubbed “Can-Am”, the new bikes would be a manufactured in Canada and sold through BRP’s existing snowmobile network. Powering the new bikes would be a line of air-cooled, rotary-valved, two-stroke engines manufactured by Bombardier’s Austrian division, Rotax.

|

|

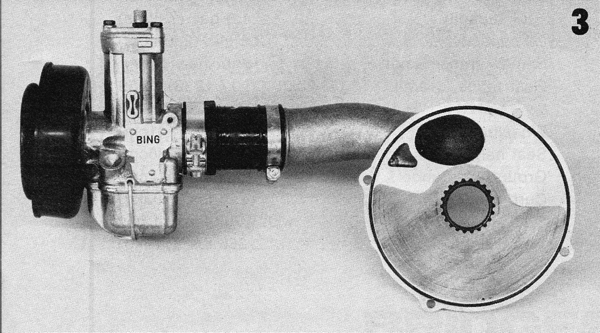

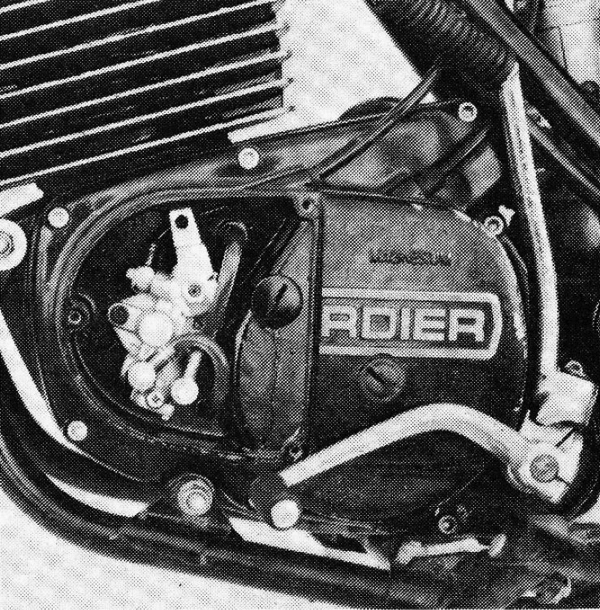

Before the days of Boyesen Reeds and power jet carbs, the Bing mixer and the rotary-valve intake were the kings of motocross horsepower. Traditionally, the downsides of this design had been complexity and packaging, as the carburetor and airbox needed to be mounted at or near the side of the motor’s crankcase. This made the motor very wide and susceptible to damage in a fall. In order to combat these problems, Rotax designed a unique intake that allowed the carburetor to be mounted in the traditional position behind the cylinder. This also allowed for the airbox to be mounted under the seat, out of harm’s way. Because of this clever packaging, the Can-Am’s Rotax mill was no more bulky than a traditional piston-port motor of the time. |

|

|

By the time the MX-3 hit the market in 1977, Bombardier was already starting to lose interest in the Can-Am experiment. Many people within the company believed their resources would be better-served by moving into the lucrative commercial transit industry. Unfortunately, this shift in priority meant less R&D dollars for the motorcycle department. As a result, the MX-3 turned out to be a budget makeover, using the existing chassis and motor from the MX-2, grafted onto longer travel suspension. Predictably, this half-hearted effort yielded lackluster results. |

The new Can-Am would make its debut in 1973 and see immediate success on the international stage. Jeff Smith 125cc (bronze), Erin Nielson 125cc (silver) and Bob Fischer 175 (gold) would all medal on the Canadian machines at the 1973 ISDE. Then in 1974, Can-Am MX machines would sweep the top three positions in the AMA 250 National Motocross championship, with Gary Jones taking the victory over teammates Marty Tripes and Jimmy Ellis. In 1975, Ellis would back up his excellent outdoor finish by dominating his way to the 1975 Supercross title. In a mere three seasons on the market, Can-Am had already claimed two of the most prestigious titles in American motocross. Along the way, the machines from the Great White North had developed a reputation for one thing: horsepower.

|

|

A new “snake-style up-pipe” re-routed the MX-3’s expansion chamber out of harm’s way, but roasted rider’s legs in the turns. |

|

|

Legend has it that the MX-3 inherited its colorful moniker by way of an off-hand comment from Factory Can-Am rider Jimmy Ellis. Ellis, having just enjoyed a prototype MX-3’s vicious handling first hand, declared the new machine a “Black Widow”. Taking this for some sort of complement of the MX-3’s badassery, Can-Am’s marketing people ordered up some spiffy Black Widow decals for the rear fender. This of course, did not sit well with US dealers who realized how this might be interpreted by consumers and refused to display them. In the end, Can-Am recalled all the decals and asked that they be removed from unsold MX-3’s. |

The Rotax air-cooled singles employed across the Can-Am line were without a doubt the fastest motors in motocross at the time. By most accounts, the 175 Can-Am was faster than most competitors’ 250’s and the stock 250 was faster than the other brands works bikes. These Austrian built motors used a unique “rotary-valve” intake that fed the intake charge directly into the crankcase via a spinning disk mounted to the side of the motor. This design offered far better control of the intake charge than the crude piston-port designs of the day and helped give the Can-Am its horsepower advantage. One drawback of this design was that it typically made for a bulky motor, with the carburetor mounted to the side of the engine cases. To combat this, Can-Am mounted its carburetor farther back in a more traditional position and ran a long manifold down to the intake valve. This gave the Can-Am a much narrower profile than a typical rotary-valve motor and put it on par with the size of most piston-port and reed-valve motors of the time.

|

|

Batten down the hatches: While horsepower was never a problem on early Can-Am’s, handling was another matter. The bikes were vague in the turns and downright scary at speed. When you combined its explosive delivery with its wayward handling, the MX-3 could be a handful for even the most skilled of motocross pilots. |

When designing the new Can-Am’s, Jeff Smith had persuaded Bombardier to use only premium components on the the machine. This meant magnesium cases for the motor, a Bing carburetor, Mikuni oil pump, Bosch CDI ignitions, Trelleborg tires, Betor forks, and Girling shocks. At the time, these were considered the best components available and helped set the new machine apart from a crowded field of competitors.

|

|

Nitro-burner: In 1977, this was by far the most powerful motor in the 250 class. At 35.16 horsepower, it had five horsepower on the other 250’s and actually rivaled some Open class bikes for forward thrust. |

|

|

While outright power was never an problem, there were other issues with the MX-3’s Rotax mill. A light flywheel, grabby clutch and explosive delivery combined to make the MX-3 a handful in slippery conditions. The transmission was also an area of concern, with one magazine at the time commenting that the MX-3 came standard with a neutral between every gear. |

After the success of the original MX-1 and MX-2, Can-Am took a fairly conservative approach to the development of the MX-3. The new MX-3 would retain the same basic motor and frame package from the MX-2, but add on a new set of long travel forks and shocks. While this was certainly cost effective, in the end, it may not have been the optimal route for producing the best overall handling package. In addition to the new suspension, the MX-3 would set itself apart from previous Can-Am’s with a bold new orange and black color scheme unlike anything else on the track.

|

|

One interesting feature on the Can-Am was the usage of oil-injection for lubrication. Usually found on two-stroke play bikes, this system pumped a constant supply of oil to the Rotax mill from a small 2.3 quart tank built into the frame’s backbone. |

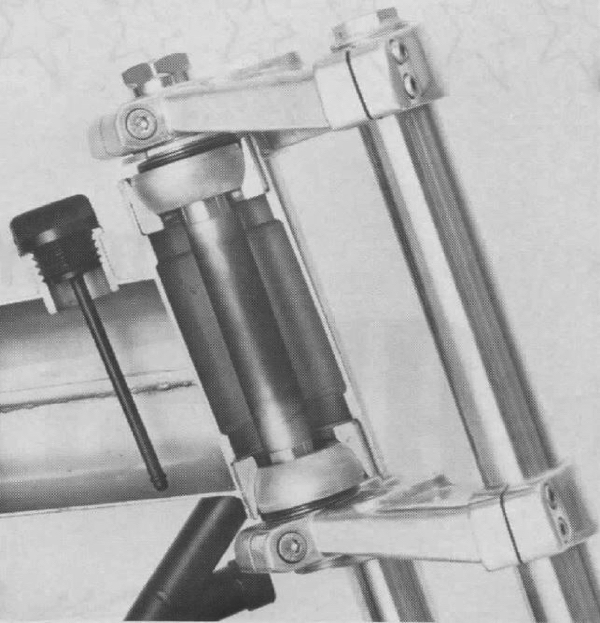

For the MX-3, Can-Am retained the same basic chassis design as the previous MX models, but made some subtle alterations to accommodate the new longer travel suspension. The basic frame itself was fairly conventional, being a double downtube design molded out of high-carbon steel. This was lighter and more expensive than the mild steel found on many budget machines, but not as light, strong or expensive as the chrome-moly steel found on high-end racing machines like Yamaha’s YZ250. Built into the frame backbone was a 2.3 quart oil tank for the MX-3’s oil-injection system and an innovative adjustable steering head. This unique feature allowed the Can-AM’s owner to alter the MX-3’s frame geometry to suit track conditions by increasing or decreasing the angle of the steering shaft. By repositioning two cones at either end of the steering head, the MX-3’s steering angle could be adjusted from 25 to 31 degrees in half-degree increments.

|

|

Another feature unique to Can-Am’s of this era was the ability to alter the bikes geometry up to six degrees through the use of two cones in the steering head. While certainly innovative, none of the adjustable settings did much to alleviate the MX-3’s wicked handling manners. |

|

|

Say WHAT!?! : In 1977, virtually every motocross bike was a blatting, fin-ringing assault on the ears. Even by these standards, however, the MX-3 was a notorious auditory offender. Virtually every magazine complained about the cacophony exiting the Black Widow’s steel silencer. |

|

|

The rear of the MX-3 featured the use of lightweight magnesium for the brake backing plate and shoes, as well as a slick cam-style adjuster for the chain. The ugly orange fenders were touted as “unbreakable” by Can-Am and with the MX-3’s passion for soil samples; you were likely to find out the truth of those claims. |

For the MX-3, Can-Am spec’d an all-new set of Italian Marzocchi front forks that punched out 8.75 inches of travel. These units were none-adjustable, but considered modern for the time with lightweight magnesium sliders and an offset front axle. Out back, the MX-3 featured a set of laid-down Canadian-built Gabriel “gas-bag” shocks that offered 8.5 inches of travel. The shocks offered no damping adjustability, but did have a five-way preload. Due to their sealed nature, the units could not be rebuilt. In order to accommodate the new shocks, a new swingarm was commissioned that increased the Can-Am’s wheelbase by ¾ if an inch.

|

|

Captain Cobalt: In spite of the stock MX-3’s shortcomings, Jimmy Eliis would take his works Can-Am to two victories in 1977. He would win both the Houston Supercross and Nashville National on his blazing fast Can-Am, but bail at the end of the year to ride for the Team Honda in 1978. |

|

|

These unique V-braced handlebars were a result of the Jones family’s time at Can-Am. They would be retired with the ’78 model year. |

On the track, the new MX-3’s Marzocchi forks offered more travel, but not an appreciably better ride than the old MX-2. Action was harsh initially, before blowing through the stroke in the later part of the travel. This combination of harsh action and poor bottoming control gave riders the worst of both worlds. Adding stiffer springs lessened the bottoming, but only exacerbated the harsh feel on small bumps.

|

|

For 1977, Can-Am spec’d a set of all-new Marzocchi forks for the MX-3. These long travel units offered 8.75 inches of travel and featured an offset axle with magnesium lower sliders. While the amount of travel was competitive, the action left a lot to be desired. Harsh initially and then too soft on hard hits, they were poor even by mid-seventies standards. |

Out back, the situation was even worse, as the spindly steel swingarm and softly sprung Gabriel shocks were no match for the MX-3’s prodigious power output. Once the MX-3 climbed on the pipe, the poor Can-Am pilot was left hanging on for dear life as the rear of the machine twisted and bucked in a fruitless quest for traction. Both the spring rate and nearly non-existent damping performance were overmatched by any sort of rugged terrain, and when you added in the explosive power you had a recipe for a trip to the ER.

|

|

Rubber Band Man: For 1977, Can-Am lengthened the swingarm nearly an inch and bolted on a set of Gabriel “gas-bag” shocks. These Canadian-built units offered 8.5 inches of travel and five adjustable preload settings, but no damping adjustments. They were undersprung and virtually devoid of any damping control in either direction. Even worse, they were bolted to a swingarm completely incapable of handling the twisting forces delivered to the rear by the powerful Rotax single. Any serious application of power left the rear of the MX-3 swapping side-to-side in a vain attempt to transmit all that torque into forward motion. |

That handling was the Can-Am’s bugaboo from the very beginning. Their motors had no problem in the max output department, but their explosive deliveries were too much for the chassis and suspensions they were bolted to. The MX-1 and MX-2 were mediocre handlers at best, but the new MX-3 was downright evil. With the steering head in the standard 30 degree position, the MX-3 was a decent cornerer. Slow turns could be executed with some level of control, as long as you were careful not to dial on too much power. At speed, however, the MX-3 was a wandering menace and just as likely to put you on your head as follow your intended path. If you were foolish enough to grab a handful of throttle, the black beauty was likely to either loop out, or swap side-to-side as the chassis twisted like a slinky. Changing the adjustable steering head did nothing to quell this nasty behavior and the bike quickly developed a lethal reputation.

|

|

Another unique feature of Can-Am’s of this era was this odd airbox arrangement. On the MX-3, the air cleaner actually sat on top of the airbox, instead of inside as on most off-road motorcycles. This led to issues, as the MX-3’s flimsy seat pan was known to deform and block airflow to the top of the filter. |

|

|

Hydrophobic: The MX-3 was blessed with what Cycle Guide described as “magical” brakes. Not for their power, however, but for their magical ability to completely disappear when exposed to water. |

In fact, the bike was so lethal that Jeff Smith reportedly refused to ride it after his first encounter with the MX-3. In another (perhaps apocryphal) incident, Can-Am Factory rider Jimmy Ellis was reported to have declared the MX-3 a “Black Widow” after crashing the machine into a spectator at a test session. Interestingly, the French Canadian brass in attendance apparently misunderstood this to be some sort of complement and commissioned a run of custom MX-3 “Black Widow” decals for the rear fender of the new machine. Once the American dealers saw this interesting embellishment, they immediately confronted Bombardier on the wisdom of attaching such a macabre symbol to the new machines and BRP quickly issued a recall to remove the spider from the rear fender. Unfortunately, the spider was out of the bottle (so to speak), and the name stuck.

|

|

The stock pegs on the Can-Am were universally panned for their their odd forward placement, lack of grip and propensity for sticking the “up” position. A lack of serration and no spring loading marked these as a poor effort even in 1977. |

To say this was PR nightmare would have to an understatement. The MX-3 and its Black Widow moniker quickly became synonymous with other monster-motored death machines like the Yamaha SC500 and Suzuki TM400 Cyclone. The new machine languished on dealer’s showrooms and Can-am was quick to pull the plug after only one year on the market.

|

|

Did you ever wonder what it would be like to ride a rocket-powered bicycle with blown shocks and a bent frame? |

|

|

In 1977, Can-Am unleased a machine that would go down in the annuls of motocross history as one of the most evil handling racers of all time. If ever there was a machine that lived up to its infamous moniker, the MX-3 was it. Brutally fast, grimly suspended and wicked handling, the 1977 Cam-Am MX-3 “Black Widow” stands together with its spiritual brother, the TM400 Cyclone, as the poster boys for seventies motocross lethality. |

The 1978 season would bring with it an all-new design that would strive to put the bad memory of the MX-3 behind it. The 1978 MX-4 would be the first of the “orange” Can-Am’s that would take the Canadian manufacturer into the new decade. Although it was much better than the reviled MX-3, the new MX-4 was no match for the quickly improving machines from Japan. In the seventies, motocross technology was moving at the speed of light and the Canadians were either unable, or unwilling to keep up. By 1979, they’d pulled out of professional motocross, and by 1987 they’d pulled the plug on the entire motorcycle operation. The “Black Widow” was the turning point in Can-Am’s brief flirtation with motocross greatness and remains to this day, one of the most infamous machines of its era.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier