For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at Honda’s first Open class motocross machine, the 1981 CR450R Elsinore.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at Honda’s first Open class motocross machine, the 1981 CR450R Elsinore.

|

|

In 1981, Honda finally gave the buying public the bike they had been begging for half a decade to receive. The all-new CR450R, certainly looked the part, but underneath that sexy exterior beat the heart of a swine. |

Perhaps no machine in history has been as hotly anticipated as the 1981 Honda CR450R Elsinore. Throughout the seventies, Honda raced Factory bikes in the Open class, but held off on actually producing a 500 class machine. Riders like Pierre Karsmakers, Jim Pomeroy, Marty Smith and Brad Lackey took the fire-breathing Factory Honda Open bikes to victory, while Joe Motocross was left to sit on the sidelines with dreams of a big bore Honda.

|

|

Factory: In the 1970’s Honda did not produce a production Open class motocross machine, but the Factory did race the 500 class both here and abroad. Ultra-trick Factory racers like this 1975 RC400 of Pierre Karsmakers’ only served to fuel the flames for a factory built big bore red machine. |

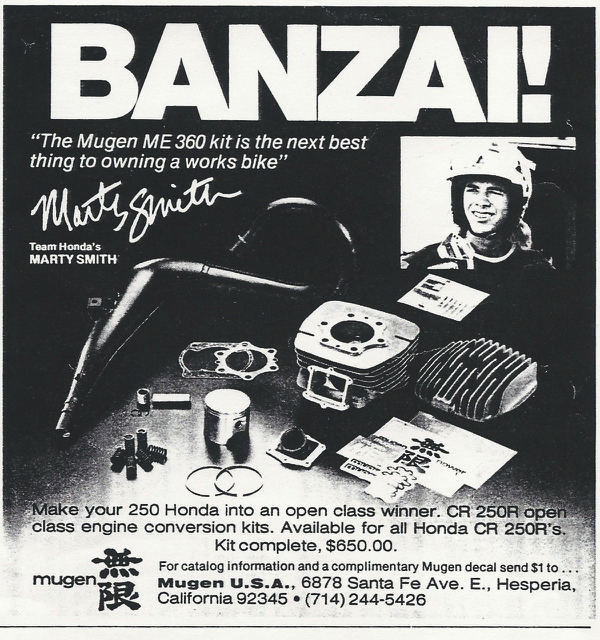

In the later part of the decade, desperate Honda devotees took to punching out their CR250R’s in an effort to build a 500 class Honda of their own. Using 360cc kits from Mugen (imported by AL Baker of XR’s Only fame), the Elsinore could be made into a competitive Open class racer. The 360 kit punched up the ponies, but did nothing for the stock CR250R’s high-strung nature. Much more akin to a ultra-powerful 125 than a trench digging 500, the Mugen 360 was fast, but demanding. For Open class racers looking to ride red, the Mugen kit was a viable alternative, but it was no substitute for a factory built machine.

|

|

Banzai!: With Honda not willing to produce a production 500, it was left up to the aftermarket to fill the big bore void. Kits like this 360cc upgrade from Mugen offered Open class performance for riders looking to ride red in the 500 class. |

|

|

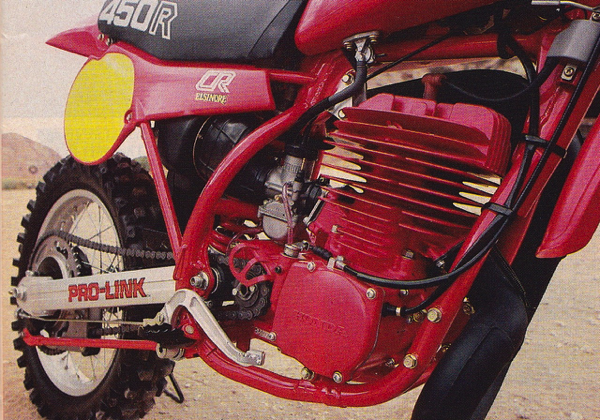

Zinger: When designing the new CR450R, Honda chose to eschew the traditional Open class route of a long stroke and major cubic inches. Instead, they settled on boring and stroking their current 250 design. This resulted in a mid-size machine that ran more like an overpowered 250 than a burly Open classer. |

By 1980, desire for a factory built Honda 500 was reaching a fevered pitch. Team Honda was coming off back-to-back 500 World Motocross Championships (and an AMA 500 National Title) and riders both here and across the pond were anxious to get their hands on a genuine RC500 replica. Early spy photo’s showed a bike that looked remarkably like the Factory machines and only served to feed the flames of consumer desire. The new CR’s looked to be the trickest Hondas ever offered, with tons of new technology stolen right off the works machines of Malberbe, DeCoster and Sun.

|

|

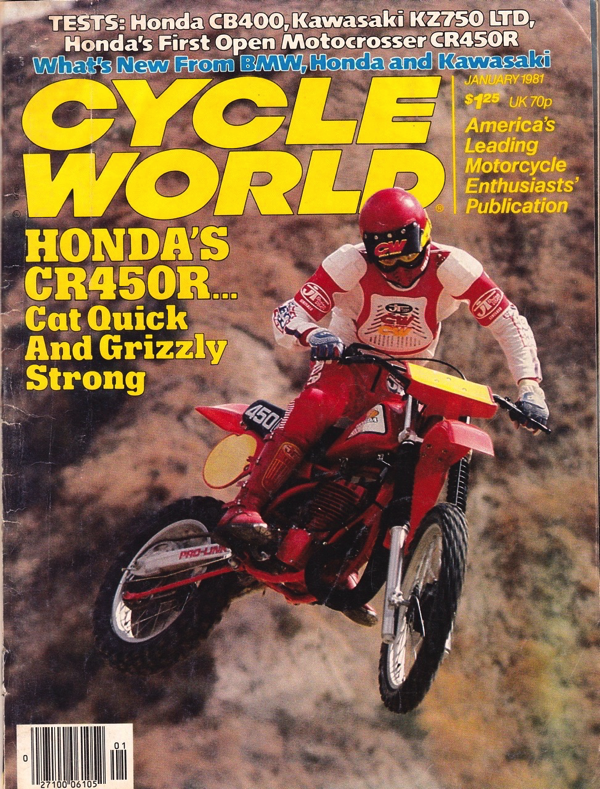

Caveat emptor: In 1981, Honda was the reigning 500 World and National Motocross champions and widely acknowledged to possess the best Factory bikes on the track. When buyers ponied up their hard earned $2138 for the new CR450R, they certainly thought they were getting a production version of Roger DeCoster’s RC500. Unfortunately, the only things the two bikes turned out to have in common were two wheels and a coat of red paint. |

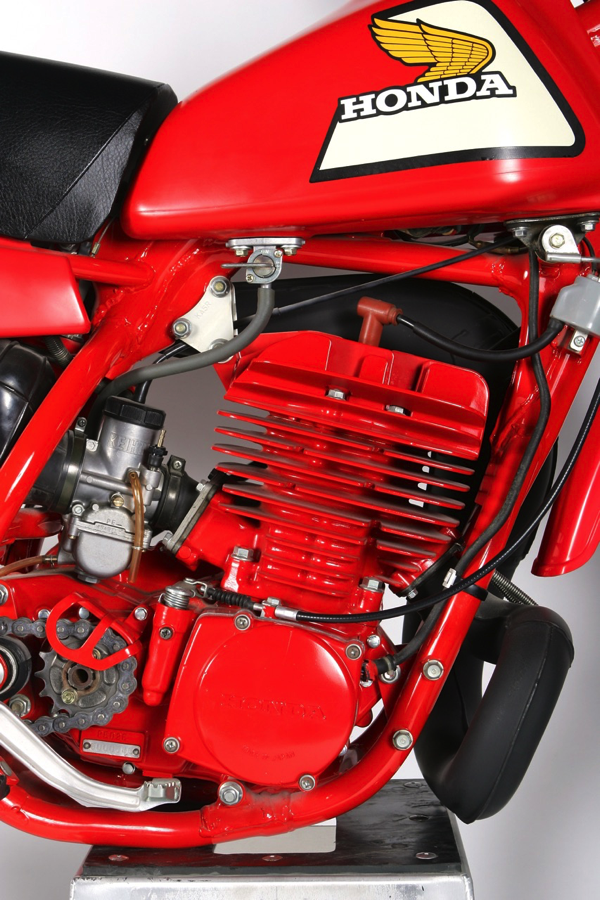

For 1981, Honda would be scrapping their complete lineup (with the exception of the new for ’80 CR80R) and coming out with all new full size machines. Best of all, for the first time, an Open class Elsinore would be joining the CR125R and CR250R. The new CR450R Elsinore would adopt the Pro-Link single-shock system used by the Factory team in 1980 and mate it to a set of massive (for the time) 41mm Kayaba forks. The motor would retain a traditional air-cooled configuration (both the CR125R and CR250R picked up water-cooling in ’81) and mate it to a new four-speed trans. New bodywork and a fresh coat of fire engine red paint were spec’d to finish off the trick new CR.

|

|

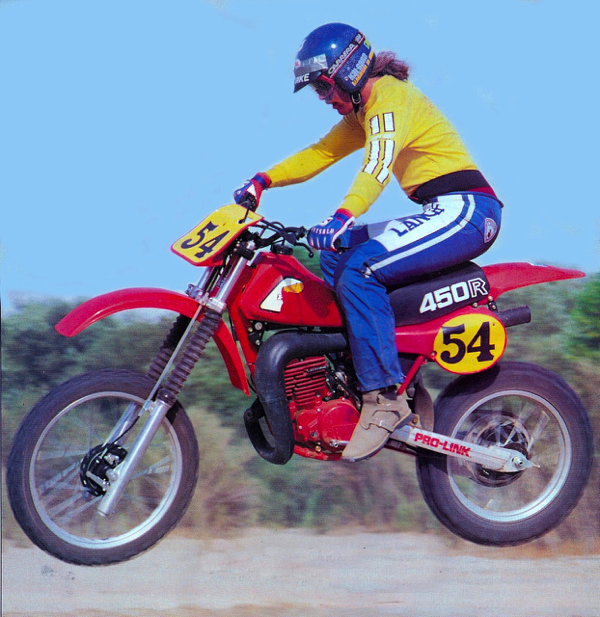

At 431cc’s, the CR450R gave up significant amount of displacement to its big bore competition. Its short stroke and light flywheel gave it a hard hitting and quick revving style of power that combined with its gappy four-speed trans, made it much harder to ride than torquey tractors like the Maico 490 Mega 2 and Yamaha YZ465. |

|

|

Cat quick and grizzly strong: History would prove the CR450R to be neither. |

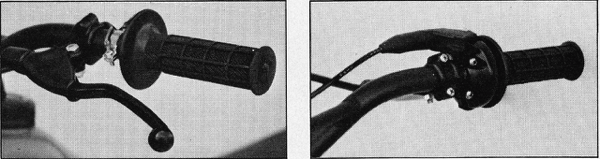

Once the bikes were released, there could be no doubt the new Elsie’s looked the part. Spacy styling highlighted a package that sweat trickness from stem to stern. Little details like a side-pull throttle, dual-leading shoe brakes and quality switchgear throughout pointed at Honda’s apparent attention to detail. Once you dug a little deeper, however, there were problems.

|

|

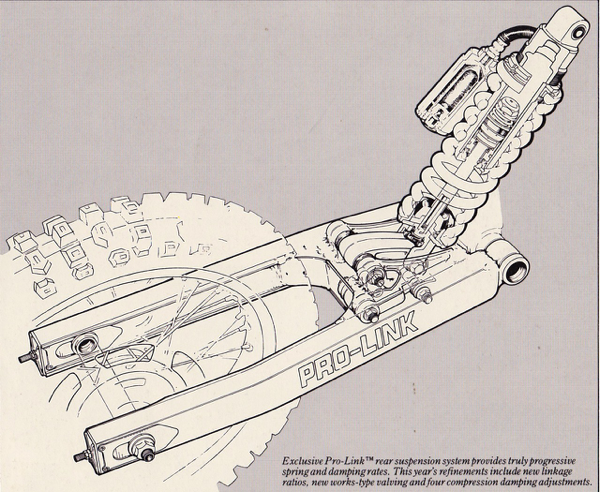

Certainly the biggest innovation to be found on the ’81 CR450R Elsinore was its single shock rear suspension system. Dubbed “Pro-Link” (for “Progressive-Linkage”), this design featured a single remote reservoir shock, mounted to a beefy alloy swingarm through a bell crank linkage that varied the shock’s speed through its stroke. Less complicated and more compact than the Suzuki Full Floater and Kawasaki Uni-Trak single shock design, this basic configuration has stood the test of time and is still in use by every major manufacturer of off road racing machines. |

First, and probably most concerning, was the new Honda’s motor, which was completely out of step with the Open class fashions of the time. In 1981, torque was the name of the game and big bore brutes like the Maico 490 and Yamaha YZ465 ruled the roost. They offered blistering performance, but mated it to a chugging and chunky style of power. They were like big powerful turbo diesels, friendly on the surface, with gobs of tire shredding torque in reserve.

|

|

On the track, the big Honda’s 431cc motor punched out a very abrupt and quick revving style of power. Low end was poor (a major oversight on an Open bike), before blasting off in the midrange with a massive dose of forward thrust. Past this explosive burst, there was no appreciable power and it was best to grab another gear instead of revving it out. |

When designing their new mill, Honda had taken the opposite approach. Instead of going for a big displacement tractor, they preferred to bore and stroke their exiting 250 design. This yielded a relatively short stroke (85mm x 76mm) and a rather smallish 431cc’s of displacement. This was significantly less than the 465cc’s of the Yamaha and 488cc’s of the ground-pounding Maico.

|

|

Kobayashi Maru: With its razor thin powerband, weak clutch (pilfered from the CR250R), oddly-spaced gearbox, and stall-prone motor, making time on the 450R proved to be a tricky proposition. Nearly every gear was wrong for its power spread and you were forced to either short shift it and fry the clutch (something the plates were not prepared to withstand) or rev it out and wait for it to stop pulling like you had sucked a gopher into the carburetor. Tom “Wolfman” Webb demonstrates this delicate dance for Dirt Bike magazine’s camera in 1981. |

On the track, the 431cc mill punched out an abrupt and very quick-revving style of ponies. Power was extremely explosive, with a sudden delivery and quick turnover. Low end was poor , before hitting like a ton of bricks in the midrange, as all 38 pound-feet of torque pored out in one massive blast. Then, just as fast as it had started, the party was over and the big Elsie demanded another shift. Thrust was non-existent above the midrange and revving it out only made it go slower.

|

|

Beautiful at rest, terrifying in motion, the mighty 450R awaits its next victim. |

With its frenzied delivery and short powerband, gear selection became critical and here the CR once again went astray. On the best Open bikes of the day, a rider could place his beast in third and rarely shift, as he rode the bikes tremendous torque curve. On the CR, that was just not possible, as its peaky powerband and quick-revving motor demanded constant shifts to keep it in its narrow sweet spot. Power delivery on the big Honda was much closer to a breathed on 250 than a monster 500, and timing these shifts was imperative to making the most of its limited power spread.

|

|

Put it away wet: Unlike most Open bikes, the 1981 CR450R required a go-for-broke attacking style on the track. Instead of sticking it in third and flowing around the track, it was necessary to hammer the throttle like a big 125 and row the gearbox to keep the big girl percolating. If you could make it work, it was capable of competitive speed, but you would be doing twice the work of a rider on a Maico or Yamaha. Cycle Magazine photo |

Unfortunately, nailing these shifts was no easy matter on the 450R. When building the new bike, Honda decided to fit the bike with only four gears. While this in and of itself was not an issue, the bike’s poorly spaced gears were. On the Elsinore, first was incredibly tall and fourth was too short. This meant just getting the CR going from a standstill required a good deal of clutch slippage (something its pathetic 250 sourced clutch was not up to) and if you were not careful, the Elsie would cough and stall.

|

|

Up front, the CR450R used a set of 41mm Kayaba sliders that punched out a full 12 inches of travel. These units offered no external damping adjustment, but they did have the ability to add or subtract air pressure to fine tune the ride via a Schrader valve on each fork cap. In stock condition, these damper-rod units were badly undersprung and underdamped for the Elsinore’s prodigious 253 pound fighting weight. On the track, they hung down in the stroke and slammed to the stops with a metal-to-metal thud on any decent sized impact. In the rough, they made the bike a complete handful, offering little or no damping in either direction. |

Once you managed to get it in motion, then the CR’s razor thin powerband and widely spaced gears left riders in a bit of a quandary. If you revved it out to pull the next gear, then the Honda fell flat on its face, if you tried to short shift it to keep it on the torque curve, then the 450 would bog. Even worse, if you geared it down to tighten up the spaces, then you were left constantly grabbing for a fifth gear that was not there. It was a classic case of lose-lose, with no easy way to rectify its mismatched powertrain.

|

|

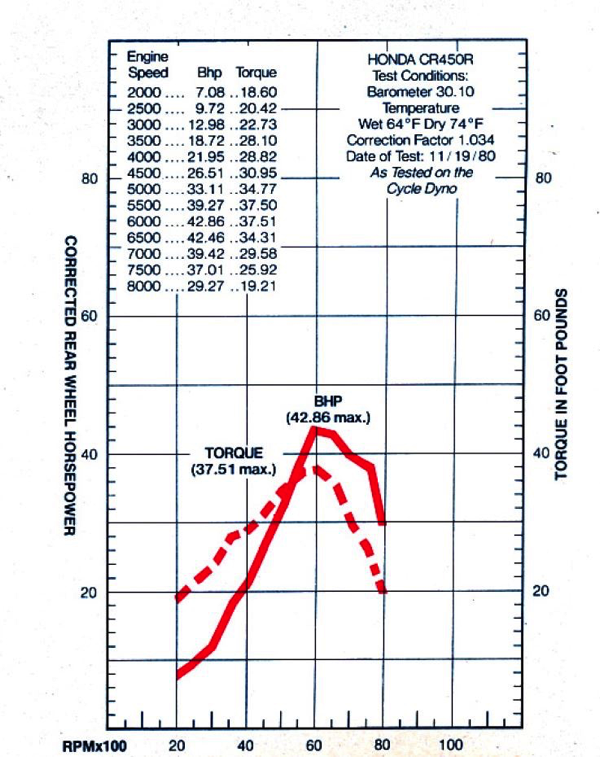

You brought a knife to a gun fight: In 1981, cubic centimeters were the name of the game in the Open class. Bikes like the fire-breathing KTM 495 MX and Maico 490 Mega 2 were quickly approaching the magic 500cc mark and mid-sized bikes like the Husqvarna 390CR were falling out of fashion. This left the 431cc CR450R on the wrong side of a horsepower war that was pushing stock outputs north of the 50 horsepower mark. At 42.86 hp, the 450R made a full ten horsepower less than the most powerful bike in the class (KTM 495) and did it over a much narrower range. |

While the 450R’s power was certainly a major concern, it was far from the last of the big Elsinore’s maladies. First and foremost was probably the Honda’s bloated weight, which tipped the scales at a waistband-busting 253 pounds. This was a staggering 29 pounds more than the class-leading Maico MC490 Mega Two and actually heavier than Yamaha’s original (and notoriously porky) YZ400F four-stroke!

|

|

The one thing 1981 CR450R Elsinore did well was corner. Its soft forks and swollen weight put a lot of weight on the front wheel and the bike exhibited decent manners in the twisties. At speed, that absurd weight, mismatched suspension and sharp geometry collaborated to make the bike a steering-head-wagging nightmare. Motocross Action photo |

This eye-opening weight figure impacted every facet of the bike’s performance and handicapped it before it even set foot on the track. At 42.8 hp, the 450R started out with 5 less horsepower than the mighty Maico and that gap widened even more when you added in the excess suet it was lugging around. On the track, the bike felt every bit of its 250 pounds and smashed into obstacles lighter bikes floated over. In the turns, it was fairly accurate, but at speed it was a runaway tractor-trailer with bald tires and a bad steering rack. Headshake was of the soil-your-pants variety and the CR could literally wrench your hands from the bars at any time without warning.

|

|

While the ’81 CR450R’s suspension looks similar to later machines, its adjustability was far more limited. The remote reservoir offered no adjustable compression damping and served only to prevent fading. The Pro-Link rear’s sole damping adjustment was a four position rebound screw at the base of the Showa shock |

In the suspension department, the CR’s components were no match for its absurd power delivery and portly disposition. Up front, a set of 41mm Kayaba forks offered 12 inches of travel and no external damping adjustment. As delivered, they were badly undersprung and underdamped, with virtually no control in either direction. Under deceleration they dove excessively and any moderate sized bump sent them crashing to the stops. Rebound was nearly non-existent and the forks were like giant pogo sticks in the rough.

|

|

One trick feature on the new CR was this sano folding shift lever. Instead of using a spring, the lever was fitted with a rubber insert that ran the length of the lever and attached to the tip. In the event of a tip over, this rubber insert acted as a rubber band and sprung the tip back into place. |

|

|

State of the art: Would you believe Motocross Action actually advised caution in 1981 when applying these works-style binders? The dual leading shoe design used a set of linkages to push the shoes apart from both sides. This offered twice the surface area when applying the brakes and a huge improvement in stopping force. For a time, these dual-leading shoe brakes actually rivaled the early disc designs for power, while offering much better feel. By 1985, all the manufactures had retired this innovative design in favor of hydraulic discs. |

Out back, the outlook was slightly better, with a huge dose of new technology. New for ’81, was Honda’s works inspired Pro-Link single shock suspension system. The Pro-Link was Honda’s first attempt at a single shock linkage system and it incorporated much of what we still see in use today. There was a beefy alloy swingarm, mated to a bell crank linkage and bolted to the bottom of a single Showa damper. The purpose of this linkage was to vary shock piston speed as the rear wheel moved through its travel and provide better bottoming control, while maintaining a smooth ride at low speeds. On the Honda, this linkage was mounted low and below the shock, offering a much lower center of gravity than the Suzuki and Kawasaki single shock systems.

|

|

Bun buster: While the basic Pro-Link layout has proven to be a winning design, its first iteration left something to be desired. The Showa shock was too soft initially, before slamming into a wall of damping force as the shock moved through its travel. Hammered kidneys and sore backsides were a common malady for Honda pilots in 1981. |

On the track, the new Pro-Link had the basic idea right, but the execution all wrong. At low speeds, the damping was too light and it liked to blow through the stroke. In the mid-stroke, the shock hit a virtual wall of damping and refused to move in the last six inches of the travel. It was both too soft and too hard at the same time and virtually worthless as a racing instrument.

|

|

Unfortunately, the Honda’s problems did not end with its X-ACTO knife powerband, plump proportions and confused suspension. The motor pinged, fouled plugs and blew gaskets. The shock faded like a snowman in July, the air filter sucked dirt like a Hoover and frame cracked like a defendant under cross in an episode of Parry Mason. Dirt Bike magazine photo |

|

|

While the overall bike was a bit of a disaster, there were a few bright spots. The grips, controls and super-strong forged levers were by far the best in the business and would continue to be a Honda staple for the next two decades |

Making matters even worse was the CR reliability, or more accurately, lack thereof. Tops on the hit list, was the Honda’s clutch, which was stolen directly off the CR250R. This unit had proven woefully inadequate on the 250, so it did not take a lot of imagination to predict how it was going to handle an over-geared 500. Any amount of clutch abuse (a necessary evil on the Elsie) was enough to smoke this pathetic unit and turn it into a lurching and dragging mess. If the clutch stayed in one piece, then it was only a matter of time until the base gasket blew. If that defied the odds, then the frame and swingarm were sure to crack. Shock hoses blew, air filters leaked and plugs fouled. Overnight, the bike that people had dreamed of for nearly a decade, turned into a nightmare of epic proportions.

|

|

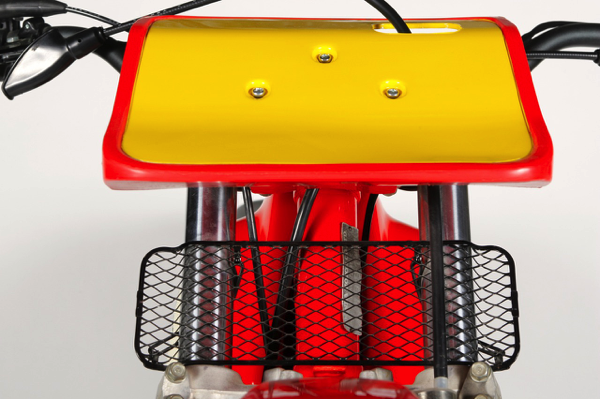

By far the most unique feature of the 1981 CR450R Elsinore was this ridiculous front number plate. Designed with airflow in mind, it was supposed to allow for better cooling to the overtaxed Elsi’s engine. In practice, all it did was make scoring a nightmare and proved no more useful than a simple vented plate would have been. Critics compared it to a snow shovel or hangnail, and most riders ditched it before the ridicule reached critical mass. |

|

|

Conical hubs and a full floating rear brake highlighted the rear of the all-new CR450R |

On the bright side, not everything was a complete failure. The bike looked great, aside from its very unfortunate front number plate. The front plate was designed to route more air to the motor, but most people found it to be an eye sore. Other than that, the plastic was of high quality and the styling was clean and highly modern. The brakes were dual-leading shoe and the strongest binders on the market. All the components were top notch and a cut above those found on the competition. Items like the forged levers (bent instead of breaking), quality grips (no need for Ourys) and slick folding shift lever showed Honda’s attention to detail in an otherwise lackluster design.

|

|

A slick rebuildable alloy silencer was still a few years into the future in 1981. |

Overall, the new CR450R proved to be a massive disappointment for Honda. While they sold thousands of them on anticipation alone, the actual product turned out to be a colossal dud. It was an ill-handling, unruly, unreliable and overweight beast that disappointed everyone who shelled out their hard earned $2148 to buy it. Quickly, Roger DeCoster and the Honda engineers realized they had made some unfortunate choices with the 450 and set about making amends with a hugely improved Open class Honda. The 1982 CR480R rectified most of the 450’s deficiencies and turned a sow’s ear into a silk purse overnight. The 480 was everything the reviled 450 was not and sowed the seeds for a decade of Honda dominance.

|

|

Growing pains: After nearly a decade of waiting, Honda finally unleashed the might of their engineering knowhow on the 500 class in 1981. It was a bike so anticipated, that potentially no machine could have lived up to the hype that preceded its launch. Even so, no one would have predicted how poorly Honda’s initial foray into the Open class would go. It was a brutal first lesson, but it was one the Honda took to heart. By 1982, Big Red would be back on track, and by 1983, they would be producing the best 500 in the business. |

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier