For this installment of GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the 500 class of 1988.

For this installment of GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the 500 class of 1988.

Once upon a time, mighty dinosaurs ruled the motocross tracks of the world. These over-muscled behemoths shredded knobbies and strained ligaments, as brave sportsmen fought to tame their unruly personalities. They were big, heavy and in possession of more power than any sane person could ever hope to need. Making the most of them took an iron constitution and a delicate touch, as any injudicious application of throttle was sure to end up in a crumpled mass of bike and rider.

|

|

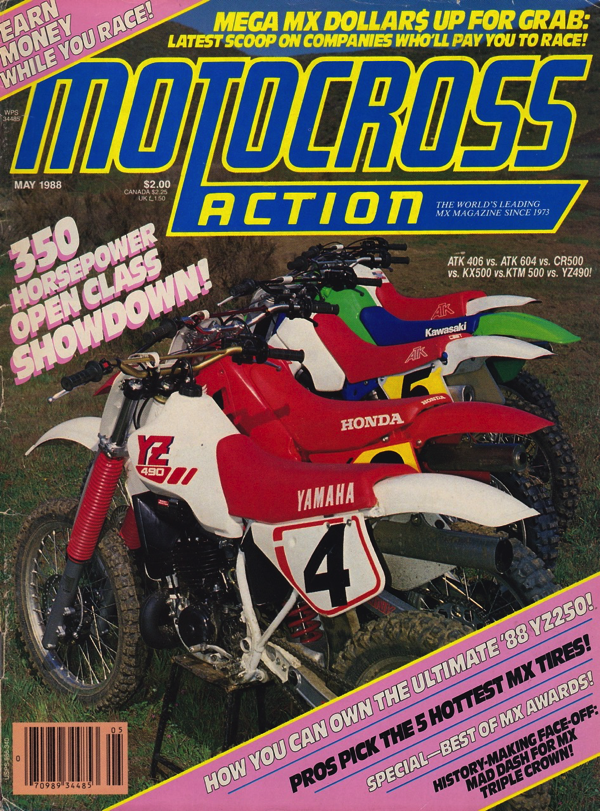

In 1988, MXA offered by far the most comprehensive 500 shootout in the business. They tested not only the big three Japanese (Suzuki killed off their 500 in 1985) five-honeys, but also threw in the best from Europe (KTM) and two slightly off-beat entries from America (ATK). |

For the brave souls that chose to race these 500cc monsters, this Jekyll and Hyde personality was a badge of courage. Racing an Open class two-stroke took skill, strength and bravery. Put frankly, they were too fast, too heavy and too scary for most “normal” people. While this added an aura of prestige and danger to the Open class, it did the bikes no favors in the marketplace. Most riders found them just too hard to live with, and over time, the fascination with the once mighty Open bikes began to wane.

By the early eighties, the rise of fast, inexpensive and reliable small bores from Japan had the taken some of the luster from the 500 class. Where once the big bores received all the latest updates, that technological advantage began to shift down to the 125 and 250 class. By 1985, Suzuki had pulled their 500 program completely and only Honda, Yamaha and Kawasaki remained interested in continuing to develop their Open class machines. Both the KX500 and CR500R adopted liquid cooling for ’85, and in 1986, Kawasaki upped the ante with the first Power Valve system seen on an Open class two-stroke, the KIPS.

|

|

In 1988, the 500 class was defiantly on the decline, but it not completely dead yet. The KTM, Honda and Kawasaki Open bikes were still receiving regular updates and offered most of the cutting edge technology found on their smaller siblings. Of all major players, only Yamaha clung stubbornly to the era of fins and boost bottles. |

KIPS stood for “Kawasaki Integrated Power-Valve System” and it gave the KX an amazingly wide and usable powerband. This was the first of the 500 motors from Japan to capture the magic of Europe’s best Open class power plants. Maico and Husqvarna had known the secret to 500 class power was to make all those ponies useable, while the Japanese had always gone for tire shredding rockets that more often than not, terrified their pilots. For 1986, Kawasaki finally got this delicate balance right and introduced their first truly good Open class machine.

While Kawasaki was wowing riders with their motor, Honda was winning awards for their amazing suspension. In 1986, Honda had introduced the unwashed masses to the joys of Factory suspension with the introduction of Showa’s 43mm cartridge forks. Used on Factory Honda’s for a nearly a decade, these advanced dampers offered incredible adjustability and a super-plush ride. Overnight, everything else on the track was rendered obsolete by these amazing forks and Honda rode a wave of goodwill on sparkling reviews of their advanced MX’ers.

|

|

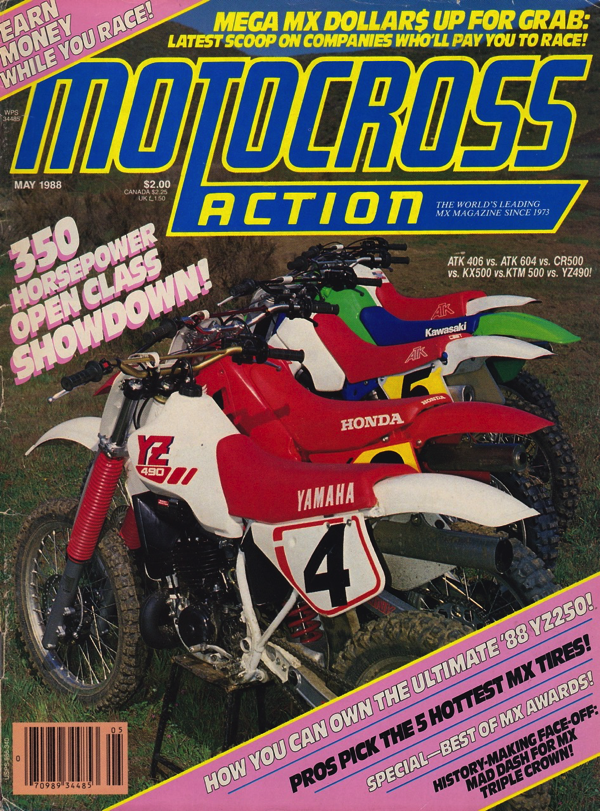

In 1988, Dirt Rider magazine eschewed traditional shootouts in favor of the “Bike Of The Year Awards”. This abbreviated format packed a lot of conclusions, but very little real info into the issue. Thankfully, the more traditional shootout format would make a return in 1989. |

For 1987, both Honda and Kawasaki decided to stand pat with their class leading power plants, instead choosing to focus on slimming down their notoriously porky layouts. At the front, these two 500 class heavyweights sparred for supremacy, while perennial also-ran Yamaha stubbornly held on to the notion that Open class riders preferred simplicity over performance. At the turn of the decade, Yamaha had offered the best Open bike from Japan by a wide margin. The YZ465 was absurdly fast, reliable and loved by riders not wanting to deal with the quirky Euros. In 1982, Yamaha bumped the beloved 465 up to a full 490 and things started to go in the wrong direction. The 490 was fast, but difficult to jet, prone to pinging and extremely porky. As the competition continued to innovate, Yamaha stubbornly stuck with this old-school power plant and by 1987, the YZ was majorly behind the times.

For 1988, the 500 class would see one of its last real injections of technology, as all the major manufacturers would finally incorporate cartridge forks into their suspension designs. While the Yamaha would retain its old fashioned air-cooled motor once again, the addition of Kayaba’s excellent cartridge forks would go a long way toward bringing their Open class entry into the modern era. In the Kawasaki camp, an all-new machine would bring with it improved power, handling, suspension and a completely new layout. Gone were the ultra-slim lines of ’87, to be replaced with a bulky and bulbous design more reminiscent of early eighties 500’s.

|

|

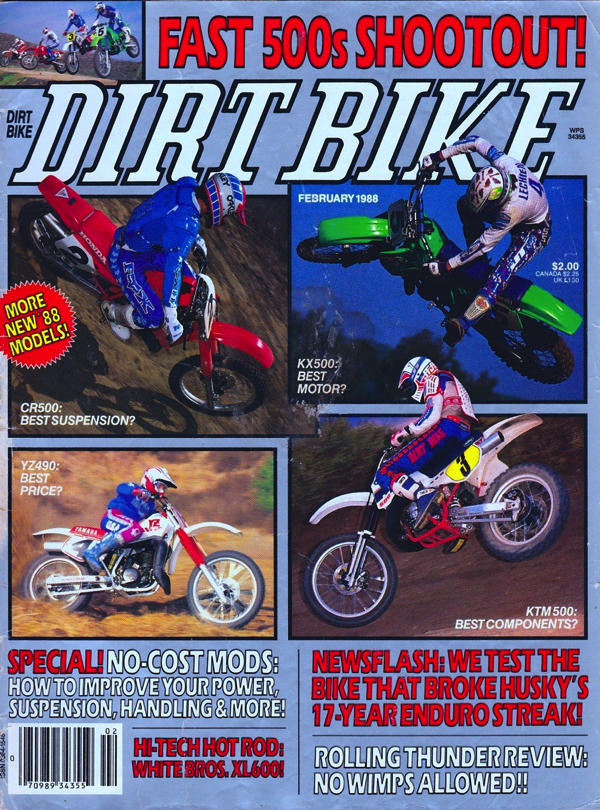

Super Moto Cross magazine trimmed its 500 shootout down to only the three Japanese in 1988. |

For Honda aficionados, a new coat of blood red paint would be the biggest change for ’88. While not as advanced in the motor department as the KX, the CR500R remained competitive with sharp handing, good suspension and a rocket-fast power-plant. Rounding out the remainder of the 500 contestants for 1988 would be one of the last holdouts of the Old World manufacturers (KTM) and a pair of entrants from the Gyros Gearloose of motorcycle manufacturers – ATK.

|

|

1988 Honda CR500R Shootout Ranking- MXA – 3rd (Out of 6) Dirt Bike – 1st (Out of 4) Dirt Rider -2nd (Out of 5) Super MotoCross – 2nd (Out of 3) |

|

|

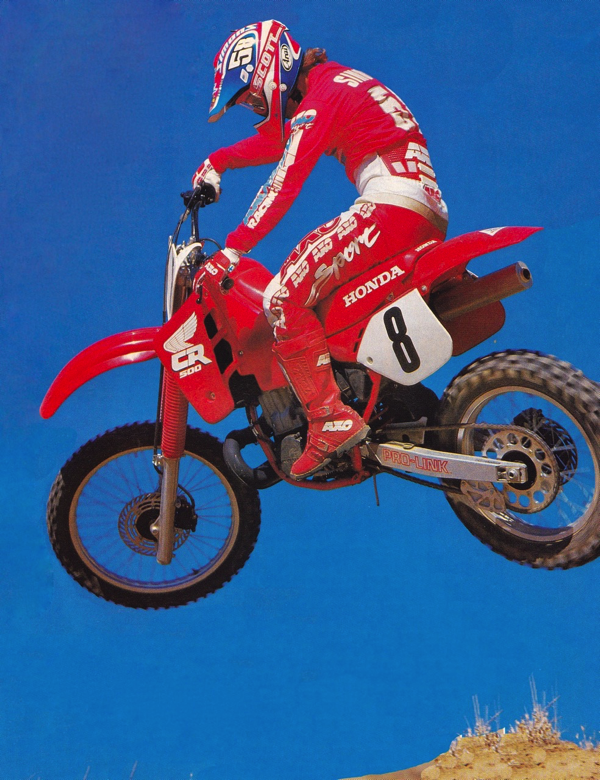

For 1988, The CR500R remained the same big, burly and beastly machine it had been in 1987. The new dark red color pallet updated the looks, but the motor remained unchanged, aside from a slight increase in crank inertia. In spite of this small attempt smooth out the powerband, the CR remained the most violent of the ’88 Open classers. Power was incredibly explosive off idle and ripped into an eye watering midrange blast. It was the type of power that shredded tires, relocated shoulder sockets and sent posers back to the 250 class. Dirt Rider Magazine photo |

In the turns, the CR carved like a fat 125, but its high-speed manners continued to border on lunacy. Headshake was violent under deceleration and lock-to-lock swaps were a common. The Showa suspension continued to be very good and was actually far better than the newer components found on the CR250R. This twitchy chassis, explosive motor and portly disposition made the bike a handful for all but the most talented of riders. It was the very definition of what made the 500 class both loved and feared. If you were man enough to make it work, it was an excellent choice, but if you preferred a little less bite to go with your brraapp, there were better choices.

|

|

1988 Kawasaki KX500 Shootout Ranking- MXA – 2nd (Out of 6) Dirt Bike – 2nd (Out of 4) Dirt Rider -1st (Out of 5) Super MotoCross – 1st (Out of 3) |

|

|

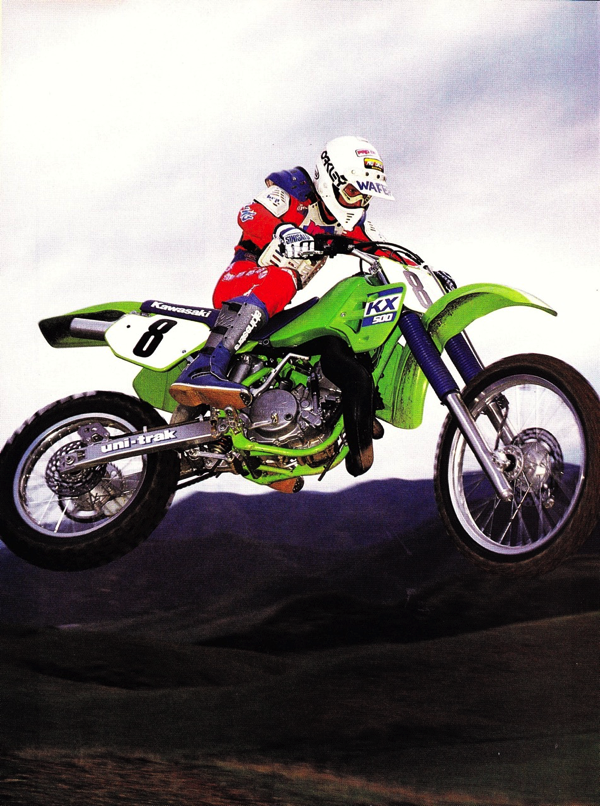

Overview – For 1988, Kawasaki scrapped their complete 1987 lineup and introduced all new machines in every class. This major redesign would actually end up being the last one the mighty KX500 would see, as this basic layout would soldier on for nearly two decades with only minor refinements. New bodywork (much bulkier and unbelievably, even more brittle than ’87), a new frame (green), improved suspension (cartridge internals finally!) and a revised KIPS-equipped motor highlighted the changes for ’88. Dirt Rider magazine Photo |

In 1988, the new KX500 offered by far the best motor in the class, with every bit as much power as the tire-scorching Honda, but far less drama. The KIPS system allowed Kawasaki to tune the big green machine for broad and smooth power that allowed riders to actually use all of its prodigious output. It was the only 500 to actually offer usable power in all three fazes of the power curve and pulled with authority from bottom to top. It could be short-shifted or revved out with equal effectiveness and proved versatile enough for both motocross and high-speed desert work.

The new suspension offered a huge improvement over the horrendous TCV fork s of ’87 and the overall package was plush and well sorted. Handling was also excellent, with solid cornering, but none of the scary headshake of the CR. In the not great department were the new ergonomics (wide, tall and fat), brittle plastic (buy fenders and side panels in bulk), marshmallow seat (hello monkey butt), cantankerous starting (bring a spare leg) and grabby clutch (don’t abuse it). Overall, the KX500 was rated the best of the Japanese 500’s by all but Dirt Bike, who favored the Honda’s suspension and turning.

|

|

1988 Yamaha YZ490 Shootout Ranking- MXA – 5th (Out of 6) Dirt Bike – 4th (Out of 4) Dirt Rider – 4th (Out of 5) Super MotoCross – 3rd (Out of 3) |

|

|

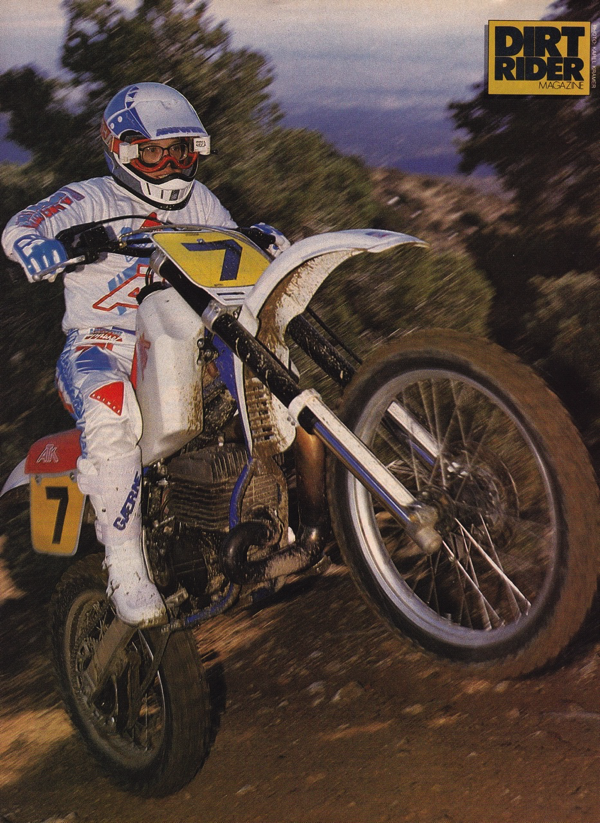

Overview – In 1988, the YZ490 was the least expensive of the Open class competitors. At $2999, it undercut the Honda and Kawasaki by $150, the KTM by $700, the ATK 406 by $900 and the ATK 604E by thousands. For that money, you got a simple and reliable 487cc air-cooled single, modern cartridge forks and rock-solid stability. In terms of outright performance, the YZ offered more than enough power, but did it in a slightly odd fashion for a 500. Both the low-end and midrange were mediocre and most of the 490’s power was focused on the top end, were few 500 riders (aside from the ever talented Rich Taylor pictured) dared to tread. Dirt Rider magazine photo |

Exacerbating the YZ’s lack of low-end was its confused jetting, which caused the bike to blubber down low and ping on top. This detonation verged on a death rattle at times and forced riders to back off well before the big Yammer got into the meat of its power. No amount of brass swapping was sufficient to alleviate this jetting conundrum and the only true fix was to have the head reshaped and switch to race gas (say goodbye to that $150 price savings).

Along with the need for engine work, teeth chattering vibration (watch the motor mounts religiously), recalcitrant shifting (notchy, thy name is YZ) and a very busy rear shock (Yamaha-hop) were also annoyances that detracted from the 490’s appeal. Braking was decent up front, but mediocre in back, with the only drum unit in the class. Still, it offered better feel than the grabby Kawasaki rear binder and more power than the pathetic units found on the KTM and ATK’s.

While the YZ was slightly behind the times in terms of technology, it did have its supporters. On the plus side were its slim layout (best of the Japanese bikes), air-cooling (no radiators to bust and simplified maintenance), very good KYB forks and excellent high-speed stability. If you fixed the motor, the YZ made an excellent play bike and a solid desert racer. For motocross, it was a bit behind the times, but if you wanted to do more than burn laps at Chicken Licks, it was a solid choice.

|

|

1988 ATK 604E Shootout Ranking – MXA – 1st (Out of 6) Dirt Bike – N/A Dirt Rider –N/A Super MotoCross – N/A |

|

|

Overview – Certainly the most unique machine to be found in any Open class comparison from 1988 had to be the thundering thumper from Southern California, the ATK 604E. The ATK featured an innovative design and hand-built craftsmanship, mated to premium quality components from all over the world. Designed and built in the USA, the ATK brand was the brainchild of Austrian engineer Horst Leitner, who parlayed his idea for a torque reducing drivetrain into a mini motorcycle empire. In 1989, ATK was actually the sixth largest manufacturer of off-road motorcycles in the world and a respected pioneer of off-road design. Dirt Bike Magazine Photo |

Introduced in 1984, the original ATK 560 was a revelation to a riding populace accustomed to overweight and uncompetitive four-stroke machines. The ATK used a massive 562cc air-cooled Austrian Rotax four-stroke single, premium Dutch White Power suspension and Leitner’s innovative A-Trak Torque Eliminator system to produce the most competitive four-stroke racer since the heyday of thumpers in the early sixties. The 560 was big, heavy and pricey (twice the cost of a Japanese 500), but also blazing fast, well suspended and exclusive.

By 1988, the American mega-thumper had adopted a new name, 604 (the 604 name was actually a marketing ploy, as the motor retained the same 562cc displacement of the original) and a much appreciated electric start. This last addition was certainly the most important, as racing four-strokes of this era were notoriously difficult to start and a simple stall could mean the end of your moto. While the addition of the electric start added to an already heavy package, most riders of the era were more than happy to put up with the extra poundage in return for the assurance the big girl would light.

On the track, the mega-motored 604E put out an incredible flow of luscious vibes. Power was nearly seamless from bottom to top and riders accustomed to the explosion of power from a two-stroke found its endless flow of torque intoxicating. There was none of the hard hit and fast revving drama common to racing four-strokes today, just a slow and metered staccato of power pulses that clawed for traction and propelled the massive machine forward at warp speed. It was both the fastest and easiest to control of the full-size Open bikes and like nothing else available at the time.

Suspension performance was excellent and tied for best in the shootout with its two-stroke stable mate. The carefully setup (individually sprung and valved at the factory for each customer’s weight and speed) White Power 4054 forks and shock (with no linkage and the benefit of the torque reducing A-Trak) offered a phenomenal ride and excellent control. The use of a countershaft-mounted disc brake centralized mass and kept the brake out of harms way, but a lack of airflow led to fade issues. Thankfully, this was less of a problem on the big thumper, due to its massive engine braking.

While the ATK 604E was picked as the best 500 of ’88 by MXA, it was still a bit of an acquired taste. The motor’s chugging delivery and extreme decompression braking took getting used to and its jaw-dropping 262-pound fighting weight demanded respect. Also, its astronomical $6950 asking price put it out of the reach of most racers’ budgets. Put frankly, it was a boutique machine for well-healed buyers that appreciated a unique flavor in their Open class racing.

|

|

1988 KTM 500 MX Shootout Ranking- MXA – 4th (Out of 6) Dirt Bike – 3rd (Out of 4) Dirt Rider – 3rd (Out of 5) Super MotoCross – N/A |

|

|

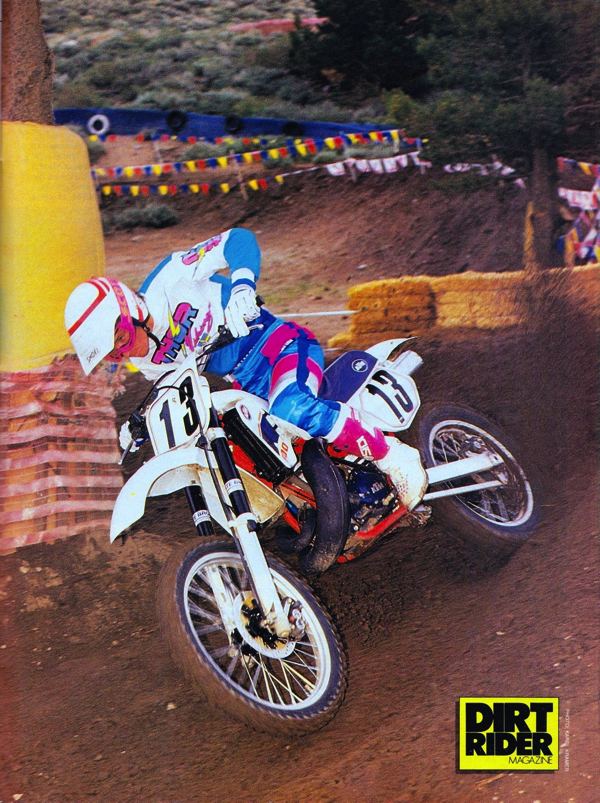

Overview – Of all the classes in motocross, the 500’s were the last to fall to the relentless march of the Japanese onslaught. As recently as 1981, the best bikes in the 500 class were built by the Germans and the Swedes, not the Japanese. By 1982, however, that lead had all but evaporated into pre-mix smoke, as excellent bikes from Japan, combined with massive missteps from the Old World brands, conspired to put the nail in the Euro coffin once and for all. The new Honda CR480R took the best traits of the legendary Maicos and offered it for less money, with better reliability and far more dealer support. Dirt Rider magazine Karel Kramer photo |

By 1988, the last holdout of the once powerful European contingent was Austria’s KTM. Once sold as Penton’s here in the U.S., KTM had proven the only brand capable of putting up a credible fight against the Japanese. They were at the cutting edge of technology with advanced suspension designs (USD forks appeared on KTM’s four years before they were offered by the Japanese) and powerful motors. KTM’s were regularly some of the fastest bikes available from any manufacturer and their fit and finish rivaled anything from Japan.

Where KTM typically went wrong (for American riders at least), was in its suspension and handling. While the suspension was advanced (premium Dutch White Power units) its setup was usually somewhere out in left field (or perhaps Lommel). Likewise, the Austrian bikes tended to offer quirky handling packages that were out of step with most American’s tastes. Turning was typically an afterthought and most KTM’s preferred the Bonneville Salt Flats to your typically tight American motocross course.

For 1988, KTM took major strides toward bringing back that lost European glory with an ultra-competitive Open class entry. The new 500 MX featured an excellent motor that was head-and-shoulders better than 1987 and very near the top of the 500 class. It ripped off the bottom and scorched through the middle, before tapering off slightly in the upper revs. Its powerband was similar to the Honda’s, but with a smoother delivery and slightly longer top-end run out. The clutch and transmission held the bike back when compared to the Japanese, however, and the bike needed to be ridden in a more laid back fashion than your typical SoCal hot-shoe. If you avoided the clutch and took your time with shifts, it was a willing participant, but if you tried to ride too aggressively, the big Austrian’s clutch and transmission would revolt.

While the motor was plenty competitive, the suspension was once again, another matter. The KTM 500 MX used the same premium White Power components that were loved on the ATK’s, but received none of the laurels of their New World counterparts. Soft springs and harsh damping front and rear relegated them to last in the suspension rankings. The brakes were also incredibly poor (no minor concern on a 60hp monster) and the rear was actually rated behind the drum found on the Yamaha. Handling was remarkably good by KTM standards and the big Katoom did a better job of changing direction that previous Austrian mounts. Stability continued to be the 500 MX’s strong suit and the bike was unshakable at speed. Overall, the KTM was a very solid effort and closer than ever before to the best from Japan. It was better than the long-in-the-tooth Yamaha, but not quite up to unseating the green and red machines.

|

|

1988 ATK 406 Shootout Ranking- MXA – 6th (Out of 6) Dirt Bike – N/A Dirt Rider – 5th (Out of 5 for MX) 1st (Out of 5 for off-road) Super MotoCross – N/A |

|

|

Overview – In 1988, ATK decided to expand its portfolio outside of the rich vet rider four-stroke market into a full line of off-road machines. They hired long time Can-Am ace John Martin (father of 2014 250 National Motocross champion Jeremy and pictured above) to develop, market and beefing up their off-road lineup. Added for ’88 were a 250 and 406, both of which to be powered by air-cooled Rotax two-strokes singles. These stone reliable and claw-hammer simple motors from Austria had been used by Can-Am in the late seventies and early eighties and were considered quite powerful in their day. By 1988, however, the era of power-valves and liquid cooling had left them a step or two behind the times. Dirt Rider magazine photo |

While perhaps not cutting edge in the motor department, the new 406 actually had a lot going for it in 1988. First of all was its weight, which tipped the scales at a jaw dropping 215 pounds. This made it a staggering 22 pounds less than the next lightest machine (the 237 pound YZ490) and actually lighter than most 250’s. The motor was also incredibly simple to maintain and there was no radiators to smash or hoses to drain when servicing the top end. The bike used the same White Power suspension seen on the 604 four-stroke and because every 406 was built to order, it was set up specifically for each customer. The A-Trak Torque Eliminator took the binding out of the rear end and the bike stuck to the track or trail like glue. Both the forks and shock were rated best in the shootout.

The motor, while no powerhouse, was quite usable and far less intimidating than a typical monster-motored 500.The 406 was actually a bit of a throwback to a time when an Open bike could actually be turned wide open without fear of looping out or being augured into the dirt. Once upon a time, RM370’s and YZ360’s ruled the roost and Open class bikes were as much about usability as staggering dyno numbers. This changed in the early eighties, but the 406 looked to put the friendly back in five-honey.

The 406’s power was smooth and linear, with no abrupt hit or surge. It was fairly soft down low (no power valve), before picking up in the midrange and pulling to a decent top-end over run. By modern Open class standards, the bike was actually pretty slow and a good running CR250R would probably beat it to the first turn. This was not the whole picture though, as the 406 was far easier to ride and less tiring than the other 500’s. Were the power shined, was away from the track, where its mellow character shot it to the top of the rankings.

Handling was excellent and the bike offered one of the slimmest layouts (in spite of its generous 3.2-gallon fuel capacity). The airbox was mounted high on the front of the tank and this helped make the 406 an absolute submarine off-road. Some riders found the 406’s low seat and high pegs confining, but the seat itself was very comfortable. About the only ATK innovation to backfire was the bike’s unique rear brake design that mounted the rotor to the countershaft. This lowered unsprung weight and centralized mass, but the tiny Gremica rotor and caliper offered little in the way of braking force and suffered from fade under hard use. Later models would actually add a third “conventional” brake to the rear wheel, thus negating any weight or mass centralization advantages of the design.

Overall, the ATK 406 was an incredibly unique expression of the Open bike concept. It was light, handled well and had phenomenal suspension, but its old-school motor held it back for top-level motocross racing. For off-road use and overall fun, however, it was really hard to beat and Dirt Rider picked it as the best Open class off-road racer of 1988.