For this edition of Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at one of the fastest motocross machines ever built, Honda’s tire-shredding 1987 CR500R.

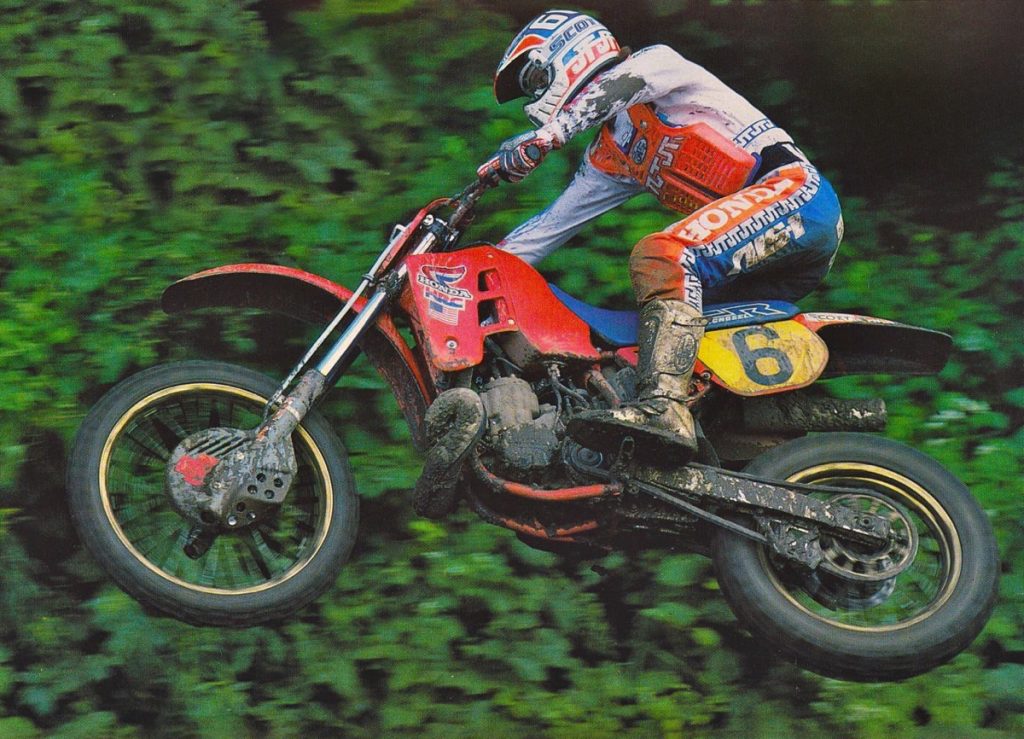

Never lacking for power, Honda’s mission for 1987 was to make that massive output more usable. Photo Credit: Honda

Never lacking for power, Honda’s mission for 1987 was to make that massive output more usable. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1986, Honda was coming off one of the most dominant years in motocross history. On the track, they captured every major championship run (at least in America), and in the press they secured victories in nearly all the major magazine shootouts. In every class, from 80 to 500, riding red was as close as you could get to a free pass to the winner’s circle.

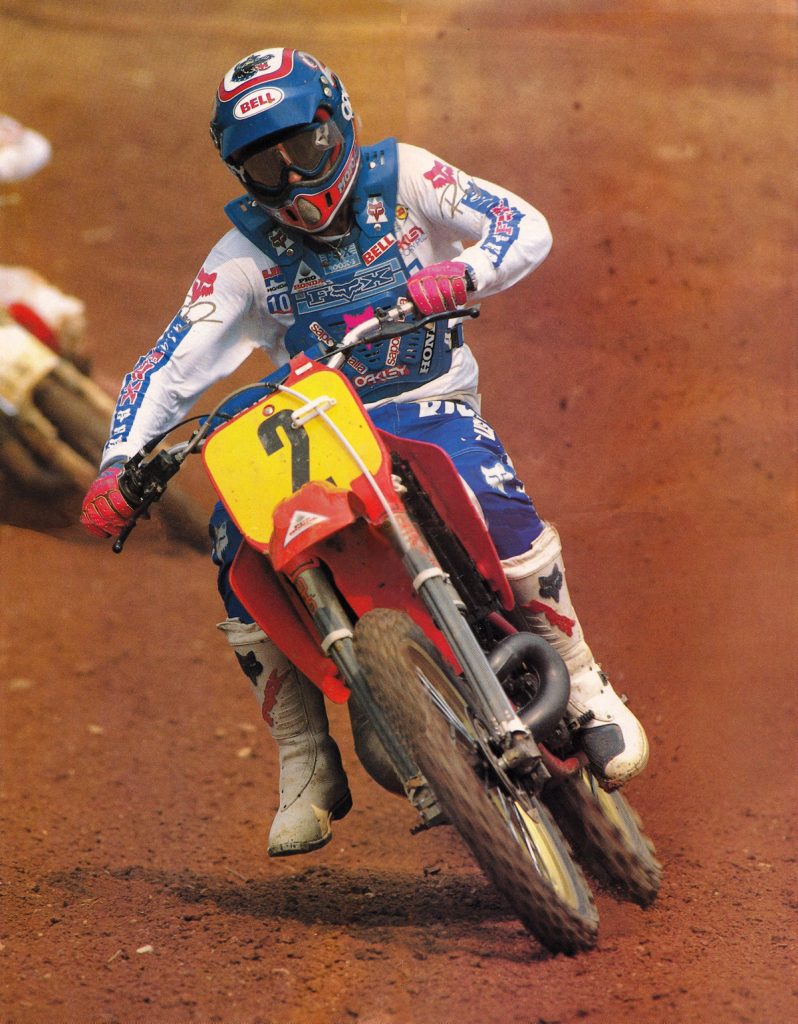

Even moto gods like 1986 500 National Motocross Champion David Bailey preferred less violence and a smoother power curve than the stock CR500R delivered in 1986. Photo Credit: Tom Riles

Even moto gods like 1986 500 National Motocross Champion David Bailey preferred less violence and a smoother power curve than the stock CR500R delivered in 1986. Photo Credit: Tom Riles

While the ’86 red machines were by far the best in their respective classes, they were not without their flaws. None of the full-size bikes had particularly good shocks and the 500 in particular could be a real handful. Its explosive power bordered on madness and it could be an absolute nightmare to start. It also had a pudgy layout that made it hard to get forward in the turns and a lackluster rear shock. The ’86 CR500R was a winner, but you needed to bring your big-boy pants to the party if you intended to make the most of its manly virtues.

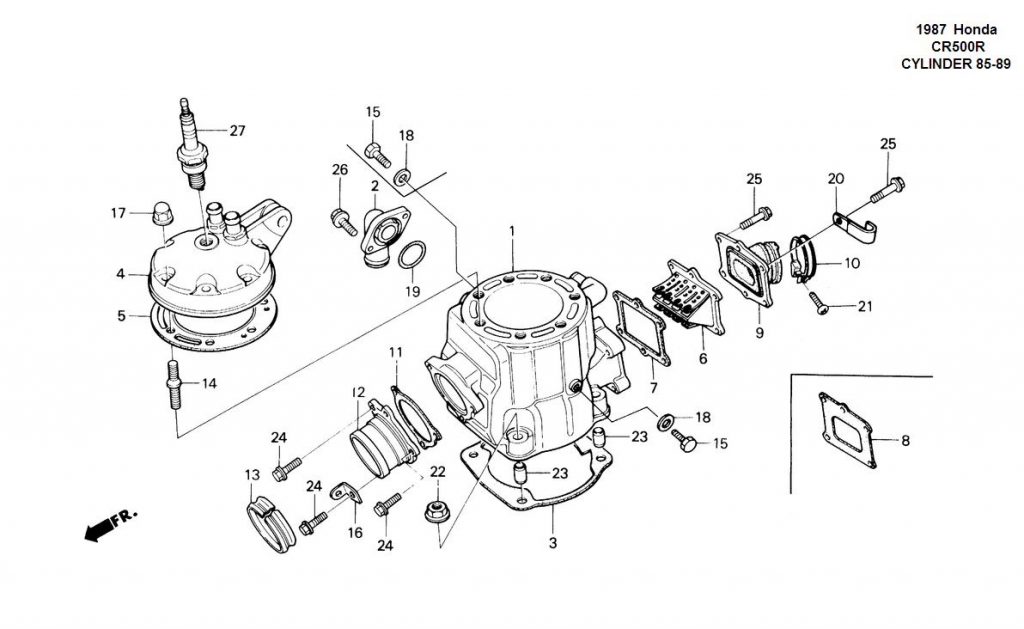

Unlike the complicated and high-tech KIPS (Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System) found on the KX500, the Honda’s top end kept it simple with only liquid cooling and a bucket-sized piston employed to deliver its immense torque figures. Photo Credit: Honda

Unlike the complicated and high-tech KIPS (Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System) found on the KX500, the Honda’s top end kept it simple with only liquid cooling and a bucket-sized piston employed to deliver its immense torque figures. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1987, Honda’s aim was to tone down some of the old CR’s more brutish tendencies, while trying not to ruin the parts of the machine that had made it such an effective racer. For the engineers, that meant easier starting, slimmer bodywork, a smoother powerband and a better shock. If they could accomplish all of that, then they might be able to build the world’s perfect big-bore racer.

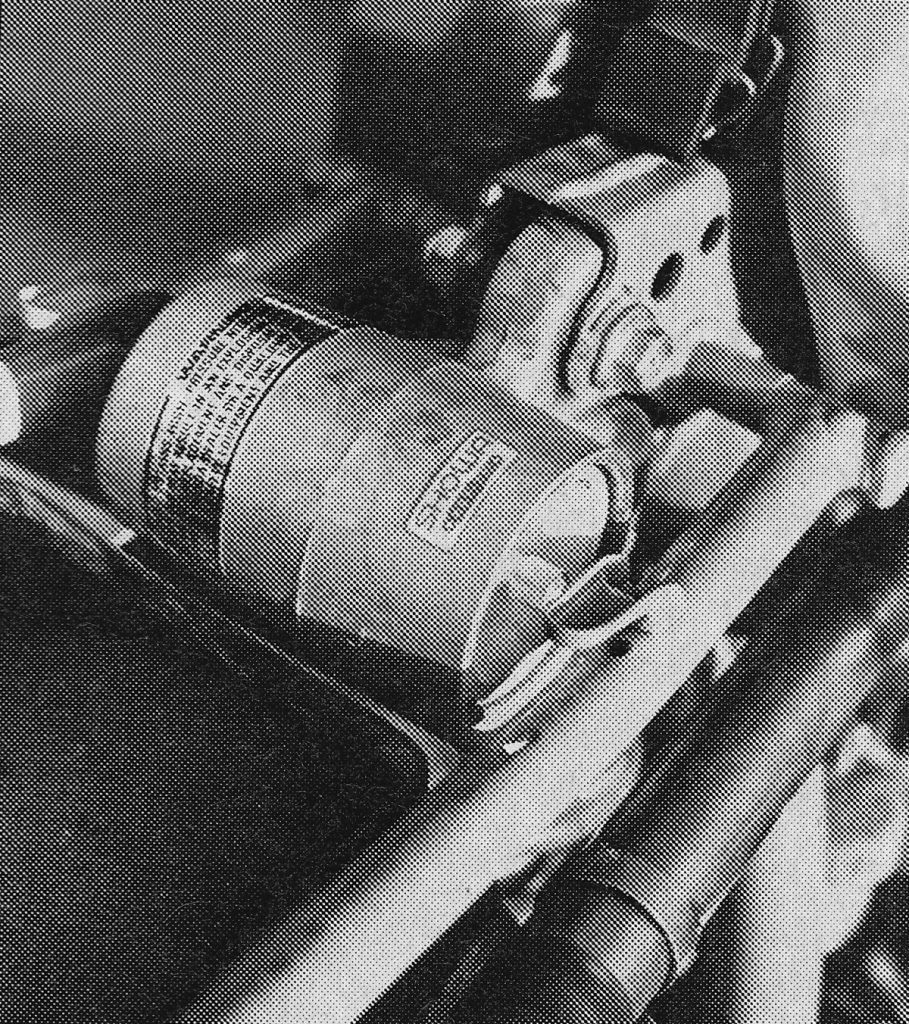

An all-new Showa shock for 1987 removed the remote reservoir and its associated hoses and clamps in favor of a more compact integrated unit. Coined “piggyback” for its reservoir position at the top of the shock body, the new damper was supposed to be lighter and less prone to hardware-related failures. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

An all-new Showa shock for 1987 removed the remote reservoir and its associated hoses and clamps in favor of a more compact integrated unit. Coined “piggyback” for its reservoir position at the top of the shock body, the new damper was supposed to be lighter and less prone to hardware-related failures. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1986, the CR500R had been one of the fastest bikes available in any class, from any manufacturer. It was an absolute beast, with a powerband that barked off the bottom and exploded with megatons of thrust in the middle. Because of its immense power, the CR was also incredibly challenging to ride. Mere mortals found it terrifying and even heroes like David Bailey and Ricky Johnson preferred a smoother and broader power delivery.

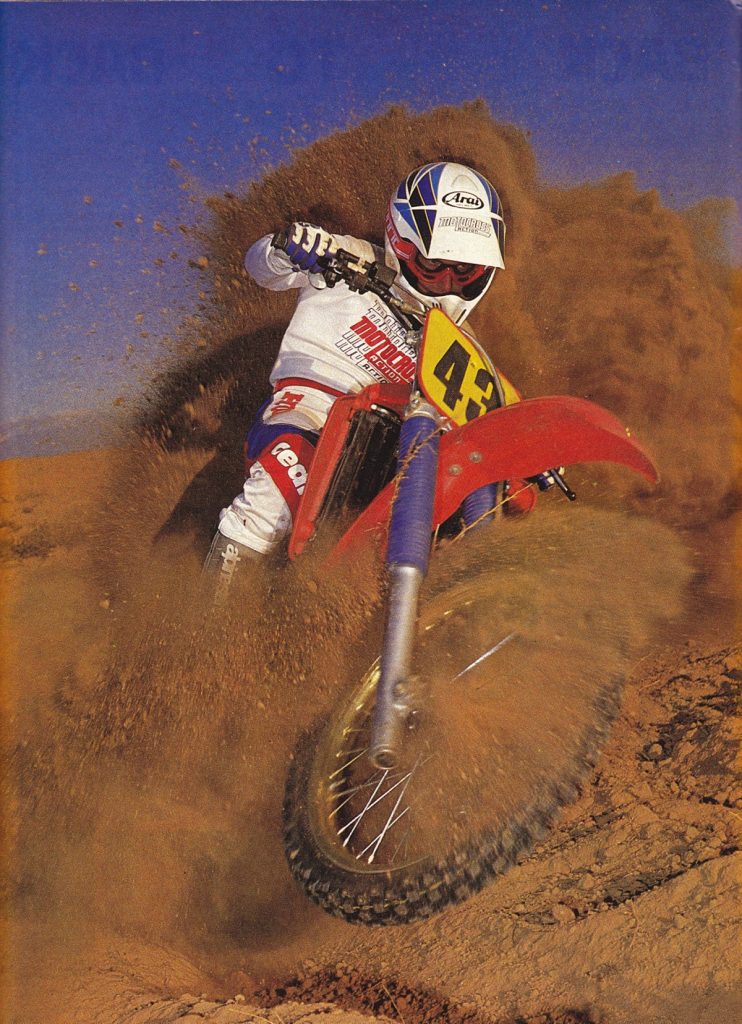

Damn the torpedoes: No berm was safe from the megatons of torque delivered by the mighty CR500R in 1987. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Damn the torpedoes: No berm was safe from the megatons of torque delivered by the mighty CR500R in 1987. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In order to accomplish this, Honda’s engineers made several small changes to the basic ’86 motor package. First up was a slightly longer (5mm) connecting rod. This was done to both increase torque and make starting the finicky 500 easier. To further aid starting, the engineers also modified the head to lower the motor’s compression slightly from 7.1-to-1 to 6.8-to-1. While the head and connecting rod were altered, the porting in the 500’s massive cylinder remained unchanged and it maintained the same 491.4cc displacement and 89.00mm x 79.00mm bore and stroke it had used in 1986. In a nod to simplicity (and probably cost), the new CR500R did not receive either the HPP (Honda Power Port) variable exhaust port found on the CR250R or the ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) exhaust gizmo used on the CR125R.

All-new bodywork slimmed the midsection, lowered the tank and lengthened the seat for 1987. Even though this was a significant improvement, the big Honda was still thicker through the middle and wider at the tank than any of its rivals. Photo Credit: Cycle World

All-new bodywork slimmed the midsection, lowered the tank and lengthened the seat for 1987. Even though this was a significant improvement, the big Honda was still thicker through the middle and wider at the tank than any of its rivals. Photo Credit: Cycle World

In addition to the internal motor changes, a new ignition was bolted on that mimicked the settings from David Bailey’s ’86 works racer. The new electronics offered less advance at low rpm and longer discharge duration for a more efficient burn. Paired with an all-new exhaust, the CR’s revised power package was designed to offer broader power, a smoother transition and easier starting, all while providing more peak performance.

Even without the benefit of power-valves or exhaust gizmos, the Honda’s 491.4cc mill produced the most power in the class. Strong off the bottom, blistering in the middle and terrifying on top, the new CR was slightly smoother, but no less potent than before. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Even without the benefit of power-valves or exhaust gizmos, the Honda’s 491.4cc mill produced the most power in the class. Strong off the bottom, blistering in the middle and terrifying on top, the new CR was slightly smoother, but no less potent than before. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

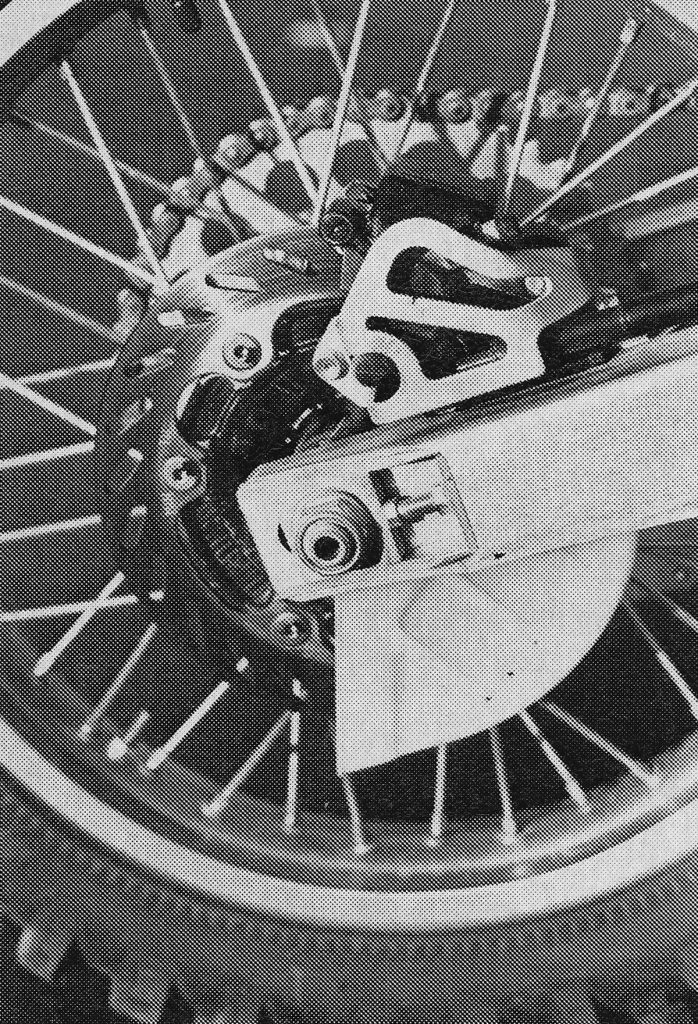

Similarly to the motor, the chassis changes for ’87 were aimed more at refinement than redesign. Overall frame geometry remained unchanged, but a new “hybrid” aluminum swingarm increased strength and reduced weight by using a combination of cast and extruded sections. The redesigned swingarm also offered a narrower profile at the rear to make room for the CR’s new rear disc brake.

In 1987, Ricky Johnson was the fastest man in motocross and the new CR500R helped power him to his first 500 National Motocross title. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

In 1987, Ricky Johnson was the fastest man in motocross and the new CR500R helped power him to his first 500 National Motocross title. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

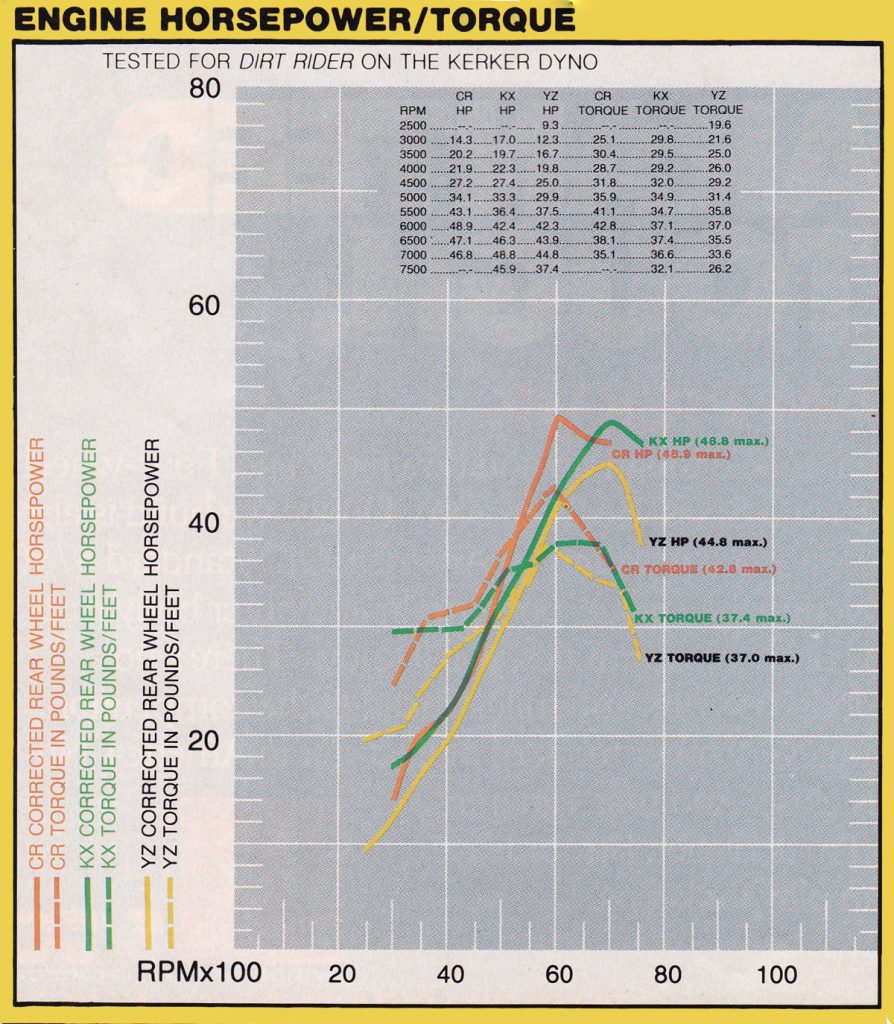

This dyno chart on the 1987 500s is full of interesting data. Firstly, it shows just how out out-powered the air-cooled Yamaha was against the competition at the time. It gave up four horsepower and almost six pound-feet of torque to the Honda. By comparison, the KX was much closer in horsepower (being edged out by only one-tenth of a pony), but still far behind in torque (37.4 vs. 42.8 pound-feet for the Honda). While we are on the subject of torque, it is worth noting that this thirty-year-old, stone-axe simple Honda two-stroke has no problem handily besting every modern 450 four-stroke in that department. While all of them blow away its relatively meager 48.9 horsepower figure (a modern 250F can actually come close to matching that), none of them can touch its massive 42.8 pound-feet of torque (most modern 450Fs put out torque figures in the mid-thirties). Since torque is actually the thing you feel when you crack open the throttle, you have a pretty good idea of just how dang fast this thing felt when you leaned hard on the loud-handle. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

This dyno chart on the 1987 500s is full of interesting data. Firstly, it shows just how out out-powered the air-cooled Yamaha was against the competition at the time. It gave up four horsepower and almost six pound-feet of torque to the Honda. By comparison, the KX was much closer in horsepower (being edged out by only one-tenth of a pony), but still far behind in torque (37.4 vs. 42.8 pound-feet for the Honda). While we are on the subject of torque, it is worth noting that this thirty-year-old, stone-axe simple Honda two-stroke has no problem handily besting every modern 450 four-stroke in that department. While all of them blow away its relatively meager 48.9 horsepower figure (a modern 250F can actually come close to matching that), none of them can touch its massive 42.8 pound-feet of torque (most modern 450Fs put out torque figures in the mid-thirties). Since torque is actually the thing you feel when you crack open the throttle, you have a pretty good idea of just how dang fast this thing felt when you leaned hard on the loud-handle. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Up front, the ’87 CR retained the same 43mm Showa cartridge forks it had used to decimate the competition in 1986. The fork’s spring rates remained unchanged, but the ’87 version did offer revised valving for increased bottoming resistance. Out back, the 500 employed a completely redesigned Showa shock that did away with a traditional remote reservoir and replaced it with a new “piggyback” design that integrated the shock and remote canister into one unit. This was done to simplify maintenance and improve reliability by doing away with the often failure-prone hose that connected the shock to the canister in the old design. While completely new in design, the internal valving of the shock remained largely unchanged from 1986.

For a big and powerful bike, the ’87 CR500R was an absolute scalpel. Front wheel traction and steering feel were excellent, with more than enough power on tap to pull you through deep sand and loam with ease. As Rob Andrews demonstrates, the big Honda had what it took to carve mean arcs in 1987. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

For a big and powerful bike, the ’87 CR500R was an absolute scalpel. Front wheel traction and steering feel were excellent, with more than enough power on tap to pull you through deep sand and loam with ease. As Rob Andrews demonstrates, the big Honda had what it took to carve mean arcs in 1987. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

While all the motor changes for 1987 were met with nearly unanimous applause, the bike’s cantankerous starting continued to be a real pain in the kidney belt. Because of the shape and position of the kickstarter, it was all but impossible to get a full kick on it without being 6’2” or standing on a crate. It also demanded a full, hard kick to elicit anything more than a pop from its silencer. If you did happen to get it going, you also had to be very careful not to foul a plug. Once it was going, it was awesome, but getting there could be an ordeal. Photo Credit: Honda

While all the motor changes for 1987 were met with nearly unanimous applause, the bike’s cantankerous starting continued to be a real pain in the kidney belt. Because of the shape and position of the kickstarter, it was all but impossible to get a full kick on it without being 6’2” or standing on a crate. It also demanded a full, hard kick to elicit anything more than a pop from its silencer. If you did happen to get it going, you also had to be very careful not to foul a plug. Once it was going, it was awesome, but getting there could be an ordeal. Photo Credit: Honda

Last up on the list of changes for 1987 was all-new bodywork that slimmed and trimmed the CR’s portly layout. In 1986, the CR500R had actually been the lightest bike in the class, but on the track, it felt the heaviest. This was largely due to its ergonomics, which made the bike feel bigger than it actually was. To address this disconnect, Honda decided to completely redesign the pilot compartment on the mighty 500.

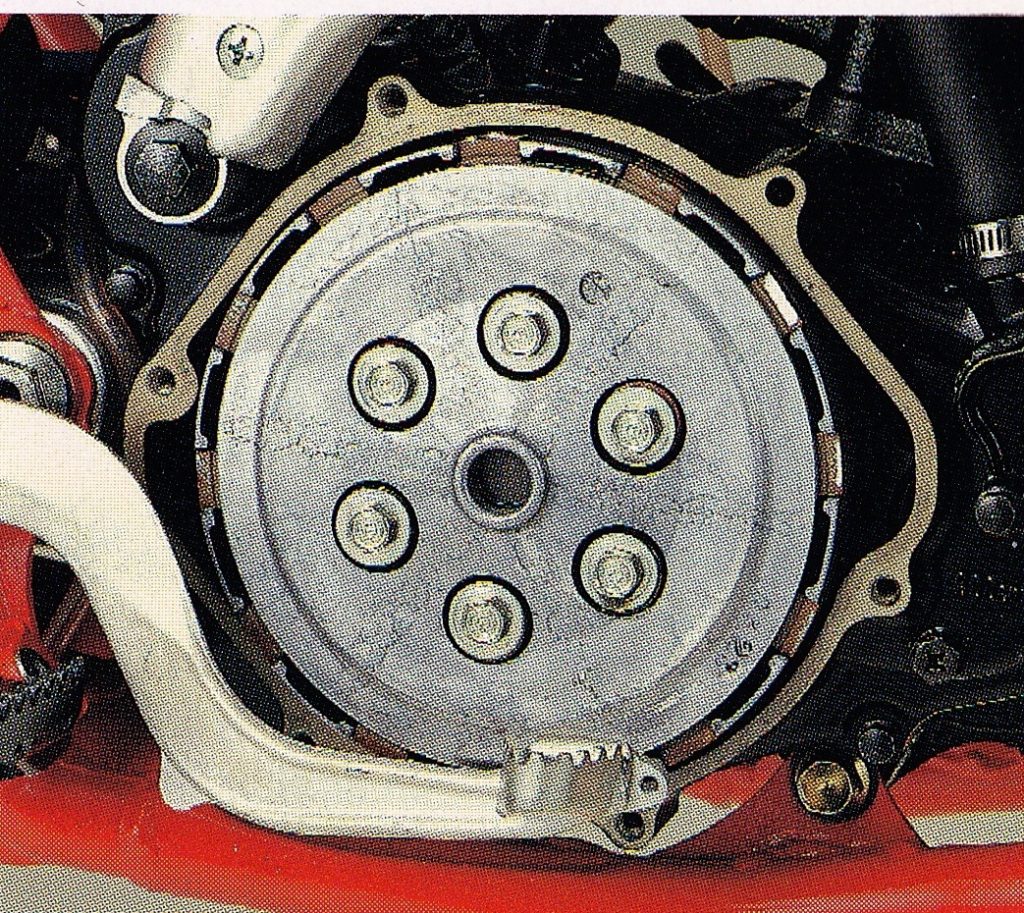

A new easy-access clutch cover on all the full-size CRs made service work much easier for 1987. Photo Credit: Honda

A new easy-access clutch cover on all the full-size CRs made service work much easier for 1987. Photo Credit: Honda

In order to lower the center of gravity and improve feel, the engineers trimmed .24 gallons off of the old tank’s capacity and lowered its position on the frame. They also slimmed it at the seat/tank junction and scooped it to make room for a longer and flatter seat. This new seat offered a slightly thinner profile for ’87 and carried farther up the tank to make it easier to weight the front end in corners. Finishing off the new rider compartment were a pair of sleek new side panels that looked great, but did not actually do much to make the bike feel thinner.

After running ultra-trick one-off works 500s in the Grand Prix for over a decade, Honda switched to a much more production-based machine for David Thorpe to defend his title on in 1987. Photo Credit: Unknown

After running ultra-trick one-off works 500s in the Grand Prix for over a decade, Honda switched to a much more production-based machine for David Thorpe to defend his title on in 1987. Photo Credit: Unknown

On the track, the ’87 CR500R was not light years different than the year before, but what changes they did make added up to a much-improved machine. The new powerband was smoother overall, with a more tractable low end and a less explosive midrange hit. It was still quasar fast, but now it no longer tried to rip your arms out of their sockets every time you cracked the throttle. As long as you showed a little restraint, the big 500 hooked up and hauled, with little drama and a lot of roost. If you pinned it to the stops and tried to ride it like a 125, it was going to swat you like a fly, but if you showed it the proper respect, it was reasonably easy to ride and brutally fast.

In 1987, there was a wide variety of machines to choose from in the 500 class. The Honda offered the most power and best forks, while the Kawasaki featured a super-slim layout and a superior shock. For those looking for simplicity, the YZ490 was king and if you just wanted to be different, the KTM offered broad power and a decidedly “Euro” feel. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1987, there was a wide variety of machines to choose from in the 500 class. The Honda offered the most power and best forks, while the Kawasaki featured a super-slim layout and a superior shock. For those looking for simplicity, the YZ490 was king and if you just wanted to be different, the KTM offered broad power and a decidedly “Euro” feel. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the handling front, the CR continued to be the best-turning bike in the Open class. The new seat and tank made sliding forward in the turns even easier for ’87 and nothing short of a 125 was going to cut underneath the Red Rooster. At speed, the CR could develop a mean case of the shakes, so desert racers were likely to be much happier with the Yamaha or KTM than the twitchy Honda. On a motocross track, however, it was without peer.

While CR500Rs marked for the USA got a smaller tank and new seat for 1987; those bound for countries like Australia maintained the .25-gallon larger tank of 1986. Photo Credit: Honda

While CR500Rs marked for the USA got a smaller tank and new seat for 1987; those bound for countries like Australia maintained the .25-gallon larger tank of 1986. Photo Credit: Honda

While the new layout was an improvement, the CR continued to be the bulkiest-feeling bike in the class. The seat/tank juncture was still wide and the raised ridge that ran around the recess for the seat could be unkind to your man parts if you slid too far forward. It was literally twice as wide at the tank as the razor-thin KX and it made the bike feel heavier than it really was. The new pipe was also a real leg-roaster and it was best to avoid short boots like AXO’s Turbo Plus if you valued the skin on your inner calf. On the bright side, the new seat was the best in the class, with a comfortable shape and the perfect density of foam.

In 1987, no forks available in the Open class could come close to the performance of the CR’s 43mm Showa cartridge sliders. Even without adjustable rebound damping, these works-style forks crushed the competition with excellent control and a plush feel. Sadly, it would take Honda more than a decade to finally eclipse their performance. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1987, no forks available in the Open class could come close to the performance of the CR’s 43mm Showa cartridge sliders. Even without adjustable rebound damping, these works-style forks crushed the competition with excellent control and a plush feel. Sadly, it would take Honda more than a decade to finally eclipse their performance. Photo Credit: Honda

On the suspension side of things, the new CR was basically the same mixed bag it had been the year before. The 43mm Showa cartridge forks continued to whip the competition with works-like performance that none of its competitors could match. Even without any external adjustments for rebound, the CR’s forks were without peer. They offered a plush feel on small bumps and excellent bottoming resistance on the big hits. They were also utterly without harshness, which was something that could not be said about any of its damper-rod equipped rivals.

With the best forks in motocross, nose-down landings were nothing to be feared on the CR in 1987. Jim “Hollywood” Holley demonstrates. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With the best forks in motocross, nose-down landings were nothing to be feared on the CR in 1987. Jim “Hollywood” Holley demonstrates. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the rear, the picture was quite a bit less rosy, however. The new Showa shock was trick, but did not really work any better than the year before. On hard hits and when under power, it worked well enough, but if you backed off slightly, it became harsh and prone to kicking. It also tended to pack down on successive hits and rebound suddenly. Worst of all, this performance got appreciably worse after a few laps, as the shock got hot and the damping faded. By moving the reservoir to the top of the shock body, Honda’s engineers simplified packaging, but also made it hard to get any cooling air to the shock. Overall, it worked better than the tooth-chattering Yamaha, but not nearly as good as the Uni-Trak rear on the Kawasaki.

While the Honda’s forks were without peer; its shock left a lot to be desired. Harsh on small stuff, prone to kicking and cursed with a terminal case of the fades, it was the weak link in an otherwise world-class package. Photo Credit: Honda

While the Honda’s forks were without peer; its shock left a lot to be desired. Harsh on small stuff, prone to kicking and cursed with a terminal case of the fades, it was the weak link in an otherwise world-class package. Photo Credit: Honda

On the detail side of things, the new CR was nearly all aces. The Honda’s shifting and clutch were easily the best in the field. No missed shifts, stubborn engagements or false neutrals here. The clutch had a fairly stiff pull, but offered excellent feel and durability, even under heavy use. If it did need servicing, it also incorporated a new easy-access clutch cover that made swapping plates a snap.

The addition of a new rear disc brake made going in deeper easier than ever in 1987. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The addition of a new rear disc brake made going in deeper easier than ever in 1987. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The brakes were also tops in the class, with excellent power and feel from its dual discs. Plastic fitment, quality and overall durability also proved a step above the class norm. It was still pudgy, but it looked great and held up to abuse far better than the competition. Everything from the material in the grips to the foam in the seat showed Honda’s all-out commitment to build the best racing machine possible.

In 1987, Honda took the meanest and manliest machine in motocross and sent it to finishing school. Trimmed, tucked and ever so slightly tamed, it came back better than ever, with polished manners and a more refined personality. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1987, Honda took the meanest and manliest machine in motocross and sent it to finishing school. Trimmed, tucked and ever so slightly tamed, it came back better than ever, with polished manners and a more refined personality. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1987, dinosaurs still ruled the earth, and none of their kind was as mighty as the scenery-blurring Honda CR500R. Like an iron fist wrapped in a velvet glove, the big five-oh-oh offered mind-bending power, combined with newfound civility. It was still a bear to start and its shock was a work-in-progress, but for hardcore racing, there was not a better Open class machine available in 1987.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com