For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at KTM’s all-new 250 Motocross for 1987.

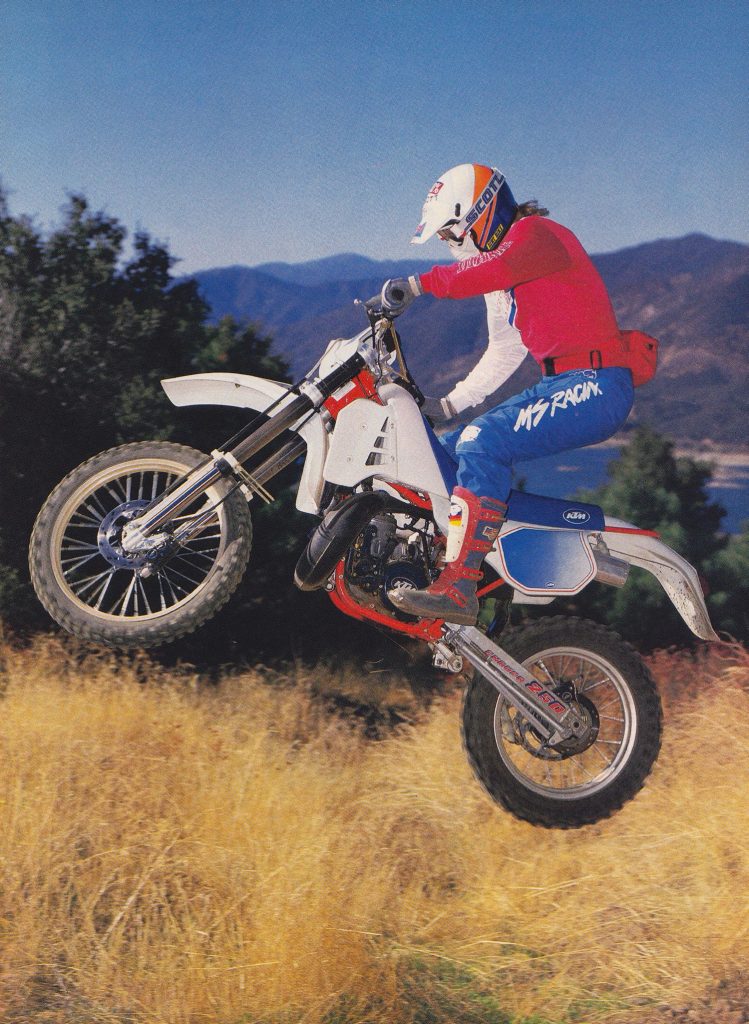

In the 1980s, KTM was still struggling for acceptance in America. For US riders, their often-innovative designs were held back by Eurocentric settings and unique design choices. Photo Credit: KTM

In the 1980s, KTM was still struggling for acceptance in America. For US riders, their often-innovative designs were held back by Eurocentric settings and unique design choices. Photo Credit: KTM

The 1980s were a tough time for the Old-World powers of motocross. After decades of dominating the sport, they were put back on their heels by an influx of competitors from Japan in the 1970s. The new Nipponese machines were less expensive, more reliable, and often, superior in performance to their European counterparts. Within a decade of the arrival of the Japanese, storied brands like Ossa, Maico, Bultaco, and CZ were on the ropes.

While KTMs in the eighties were considered second-tier motocross machines in the US; they suffered no such stigma in Europe. Across the pond riders like Heinz Kinigadner and Kees van der Ven took the Austrian machines to multiple victories and in the case of Kinigadner, back-to-back 250 World Motocross titles. Photo Credit: KTM

During this period of turmoil, one of the few European brands to keep pace with the Japanese was KTM. Started in 1934 by Austrian engineer Hans Trunkenpolz, KTM had been a late entry to the motocross game. Prior to the seventies, KTM’s main focus had been small street machines and scooters. It wasn’t until 1973 that they finally released their first true motocrosser, the 250 Cross. Coincidentally coinciding with the release of Honda’s first Elsinore, the new KTMs proved more than competitive on the international stage. Sold in the USA as Pentons, KTM 250s would capture three World Motocross titles in the 1970s with Russian hero Guennady Moisseev at the controls.

A new chassis for 1987 shortened the wheelbase, steepened the geometry, and lowered the radiators to improve handling. Photo Credit: KTM

By the mid-eighties, KTM had supplanted all of its European rivals as the only true competitor to Japanese dominance. In America, they remained more of a curiosity than a major player, but in Europe, they continued to rack up GP wins and World Titles. With innovations like water-cooling (1981), a fully removable subframe (1983), case-reed (1984), inverted forks (1985), and dual-disc brakes (1986), the little firm from Mattighofen proved it could go toe-to-toe with the Japanese on a technical front. It was only in the intangibles that they suffered compared to the Big Four Japanese brands.

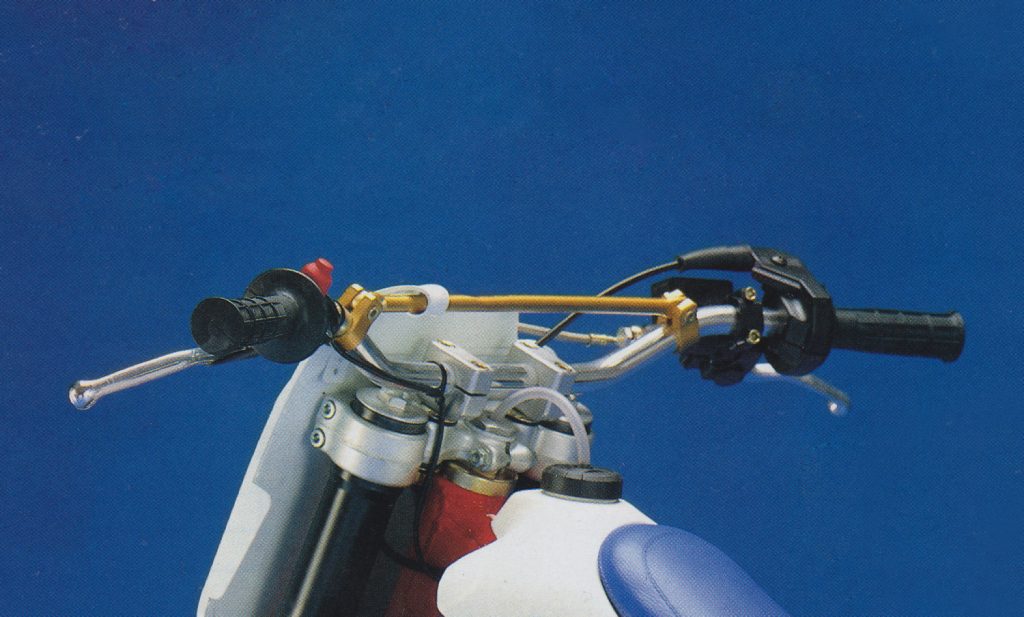

Even in the eighties, KTM offered a level of components above what was found on a typical Japanese machine of the time. It would take the Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki, and Yamaha another decade-and-a-half before they would finally start installing aluminum bars as standard equipment. Photo Credit: KTM

Because KTMs were primarily developed for the European market, they offered a “feel” that most American riders found alien. The handling, power, ergonomics, and suspension of the Austrian machines were tuned for a sport that had become very different from its US counterpart. The influence of Supercross and the American’s emphasis on the small-bore classes had led US tracks to become ever tighter and more strewn with jumps in the eighties. This contrasted greatly with the fast, smooth, and flowing natural courses the big bores of Europe favored.

In the eighties, KTM America’s off-road program was much more successful than its motocross efforts. In 1987, they finally broke Husqvarna’s stranglehold on the National Enduro championship with Kevin Hines at the controls. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

This divergence in disciplines played itself out in the riding styles of the riders and the setup of the bikes. Because of their different feel, the European machines became a hard sell to most American riders who had cut their teeth on the Japanese 80s and 125s. By the mid-eighties, it was rare to even see a Cagiva, M-Star (formerly Maico), Husqvarna, or KTM at a local track on this side of the pond. To most American riders, the Euro machines were oddball bikes, for oddball riders.

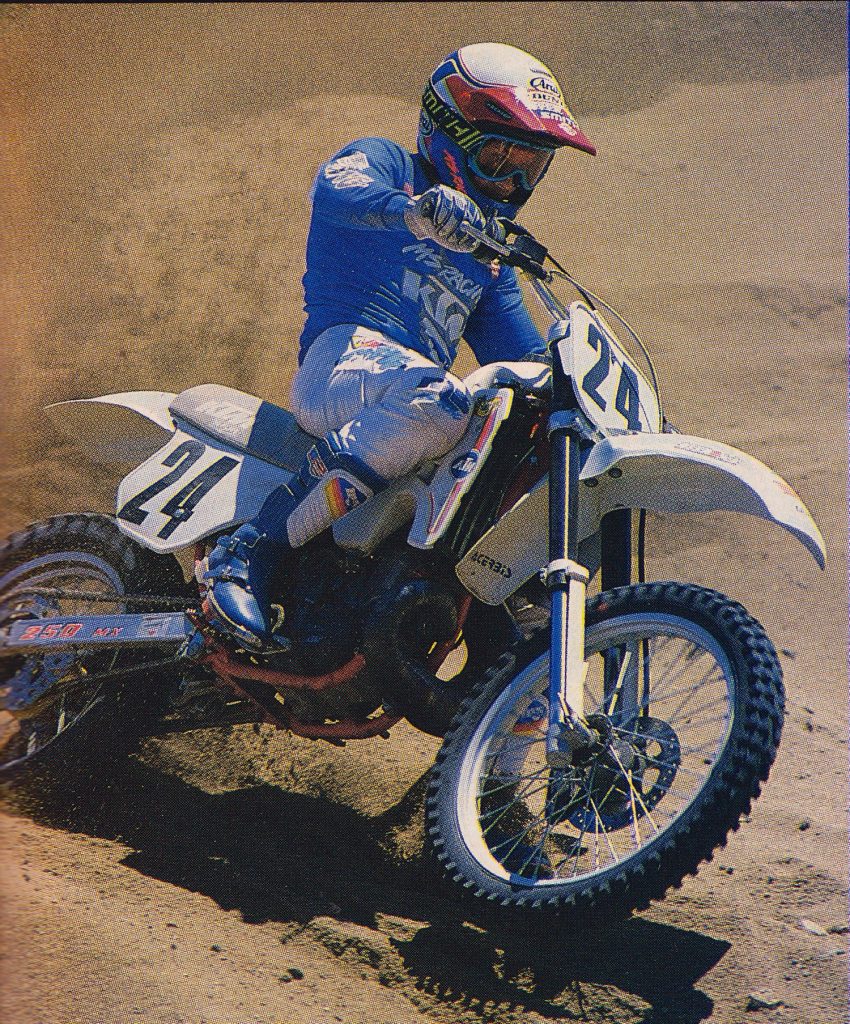

The layout on the ’87 KTM 250 was slimmer, more compact, and far more comfortable than past Austrian efforts. In spite of being no lightweight, several riders commented that the new KTM felt more like a Japanese 125 than the typically large-feeling European 250s. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Seeing this writing on the wall, KTM began a campaign in the mid-eighties to try and mainstream their motocross lineup. They knew that if they were going to escape the fate of so many of their European rivals, they would need to make their bikes more appealing to the US market. This meant dialing in sharper turning, improving the ergonomics, adding a more aggressive powerband, and setting up the suspension for Saddleback instead of Sverepec. By keeping their traditional European quality and sprinkling in a bit of Japanese flavor, KTM believed they could provide a machine that would turn the tide against their far-East rivals.

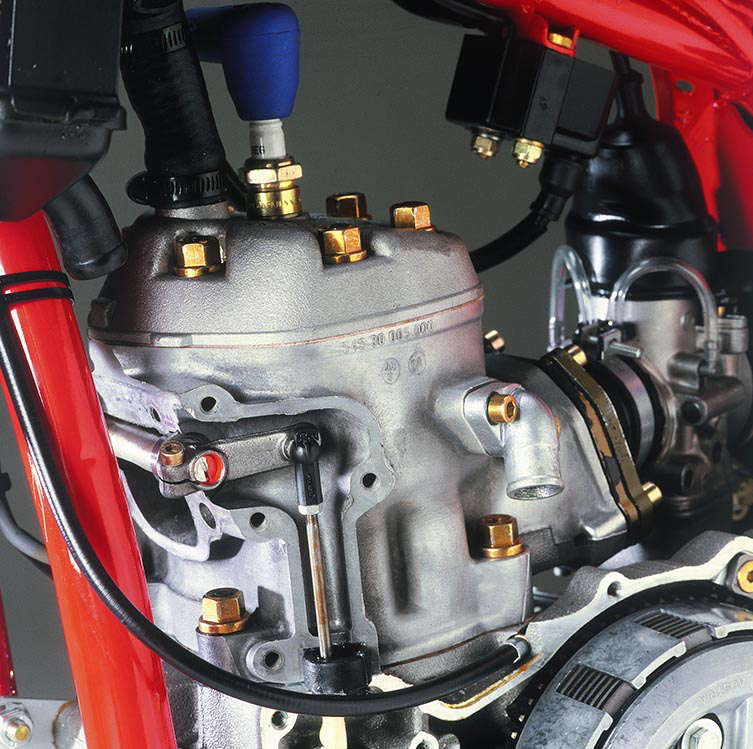

An all-new motor for 1987 incorporated a variable exhaust valve for the first time. Dubbed the “Power Exhaust Port,” this new design gave the KTM a snappy and potent powerband that was competitive with the best motors from Japan. Photo Credit: KTM

In order to accomplish these lofty goals, KTM dialed up an all-new 250 machine for 1987. The bike was redesigned from stem-to-stern, with a new chassis, reconfigured motor, and revised bodywork. Some quirks, like the left-hand kickstart, remained, but many others, like the concrete-hard seat foam, were ash-canned in favor of a more glut-friendly alternative. Like previous KTMs, the new 250 motocross maintained its reputation for quality components with trick aluminum bars (decades before the Japanese had this feature), high-quality plastic (Acerbis), Zerk fittings on the linkage (hurray!), long-lasting forged pistons, and premium White Power suspension components.

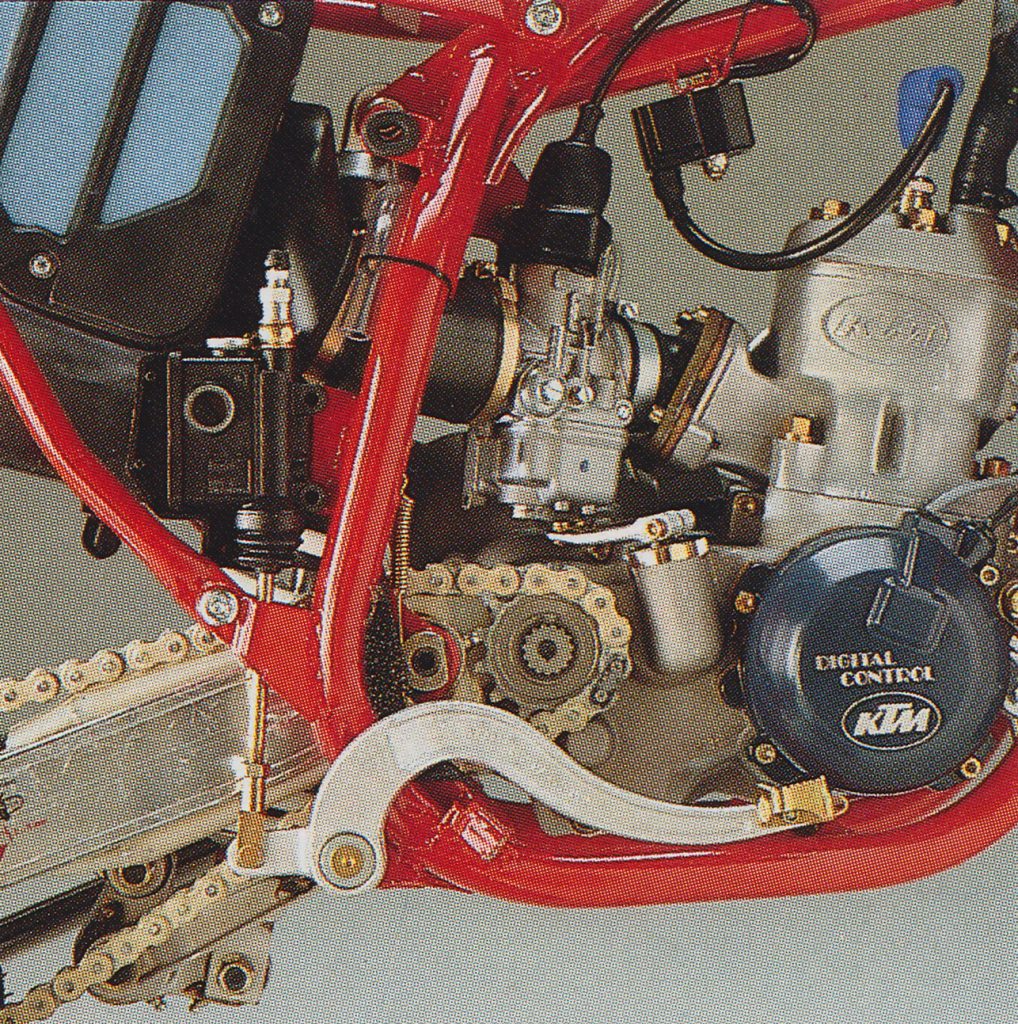

With its left-hand kickstarter, Dell’Orto carburetor, fancy Digital Control Ignition, and massive rear brake master cylinder, the KTMs were certainly unlike anything on the track from Japan in 1987. Photo Credit: KTM

On the handling end of things, the KTM engineer’s main plan of attack for 1987 was to improve the turning on their middleweight machine. Typically, most European machines of the time tended to favor stability over the cut-and-thrust maneuvers of the Japanese. This was appropriate to high-speed tracks like Gaildorf and Roggenburg, but not ideal for the tighter confines of most US circuits.

With a shorter wheelbase, a more aggressive geometry, improved ergonomics, and a snappy power, the 1987 KTM 250 was the best turning machine the Austrians had offered up to that point. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

For 1987, KTM addressed this by dialing up an all-new frame for their deuce-and-a-half. The new frame was still formed out of tough chromoly steel, but it featured a half-inch shorter wheelbase and a one-degree steeper head angle than 1986. The new chassis lowered the center of gravity by dropping the seat height, lowering the radiators, and repositioned the motor. The redesigned frame also incorporated an all-new Pro-Lever linkage and a redesigned alloy swingarm. This, combined with the new motor placement shifted the weight bias forward for increased front-end traction. The new frame continued to offer a handy removable alloy subframe, a feature only one of the Japanese manufacturers (Honda) offered in 1987.

With virtually no motocross racing presence in the US, a Factory KTM like this one of Marcus Hansson was a rare sight on this side of the pond in the 1980s. Photo Credit: Unknown

Further aiding handling feel was the KTM’s beefy 4054 White Power (known as WP today obvious reasons) inverted forks. In 1987, upside-down forks were still quite a novelty and rarely seen outside of factory equipment. With their large upper sliders and reduce under-hang below the axle, these Dutch units provided a much less flexy feel in the rough and more precision in the ruts. With cartridge internals, adjustments for compression and rebound damping, and 12.2-inches of travel, these 40mm units were at the cutting edge of suspension technology in 1987.

In 1987, these 40mm 4054 White Power inverted cartridge forks were the most advanced units in motocross. In spite of their high-tech design, they failed to live up to their sexy appearance on the track. Poor setup left them too soft for any serious motocross work and prone to harsh bottoming when pushed. Photo Credit: KTM

Out back, the ‘87 KTM 250 continued the Dutch theme by employing a White Power “Super Adjuster” shock to handle the damping duties. This piggyback gas/oil unit offered 12.6-inches of travel as well as adjustments for compression and rebound. There were seven compression and eleven adjustable rebound settings available to go with spring preload to fine-tune its performance.

In the rear the ’87 KTM employed a high-dollar White Power “Super Adjuster” shock that offered seven adjustments for compression and eleven for the rebound. Unlike the front forks, this unit was set up well and in the ballpark for most users. Other than a slightly quick rebound, this was one of the better rear ends of 1987. Photo Credit: KTM

On the motor side, KTM pulled out all the stops in 1987 with an all-new “Power Valve” design that looked to boost performance to the front of the class. In 1986, the buzz word at KTM had been Digital Control Ignition. This microprocessor-enhanced ignition had been employed to allow the motor’s spark timing to more closely follow the engine’s power curve. Instead of advancing timing at a set rpm, the new DCI minutely changed the park advance constantly to best match the needs of the motor.

By the mid-eighties, the Japanese had a firm stranglehold on the 250 division. If you were going to ride something other than a Big Four machine, you were going to need a pretty strong rebellious streak or have a dad that owned a Euro dealership. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For 1987, the DCI was back and paired with an all-new variable exhaust valve design KTM coined the PEP (Power Exhaust Port). Like other similar designs from Japan, the PEP employed a centrifugal-ball governor to control its action and ramp the port open as rpm increased. The PEP was similar in theory to Yamaha’s YPVS as it varied the exhaust port height rather than changing the exhaust pipe volume like Honda’s ATAC or Suzuki’s AECV.

The new motor on the ’87 KTM provided a strong and responsive low-end surge that climbed into a beefy midrange hit. Top-end power was virtually nonexistent, but the motor was more than competitive as long as you did not try to wring it out like 125. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The new motor on the ’87 KTM provided a strong and responsive low-end surge that climbed into a beefy midrange hit. Top-end power was virtually nonexistent, but the motor was more than competitive as long as you did not try to wring it out like 125. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Other than the DCI and PEP, the rest of the ’87 KTM 250’s motor was fairly conventional for its time. Displacement was set at 247cc, with a 67.5 x 69.0mm bore and stroke, and a 9:1 compression ratio. The cylinder was liquid-cooled and lined with a works-style Nikasil coating to allow for tighter tolerances and improved heat transfer. Unlike the ‘87 KTM 125, the 250 eschewed a case-reed intake and maintained a traditional cylinder-reed arrangement. Fuel and air delivery duties were handled by a 38mm Dell’Orto carburetor and an all-new airbox that was enlarged and opened up with additional intakes on the sides for 1987.

The real Achilles-heal of the new KTM mill turned out to be its clutch and transmission. While durable, neither unit offered the refined feel of the Japanese competition. Shifting under power was all but impossible without backing off the throttle and the clutch was grabby and difficult to modulate. Photo Credit: KTM

On the track, the new KTM 250 Motocross turned out to be a solid improvement in nearly every way over previous KTM machines. The new PEP motor carbureted well and snapped to attention at the first crack of the throttle. It was the easiest starting bike in the class (as long as you could kick left-footed) and put out a solid low-to-mid hit that blasted the Austrian machine out of tight turns with authority. It was far freer-revving that previous KTM efforts, which had often felt like they were tuned for Enduro usage. On the top end, the 250MX laid down its sword and surrendered, but from turn-to-turn, it was as fast as anything in the class.

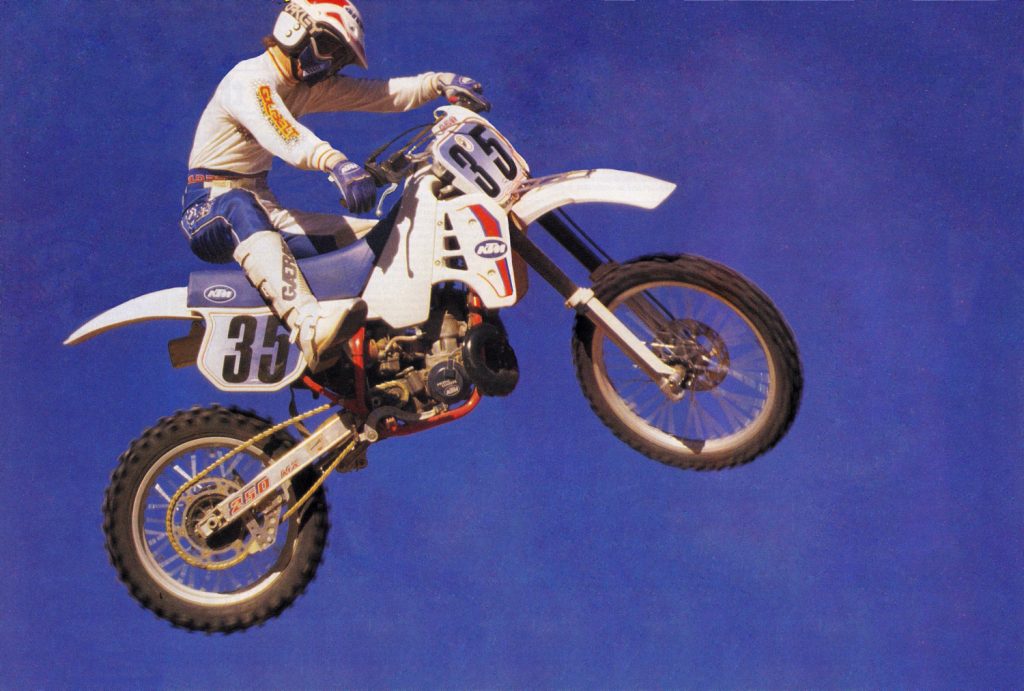

With its responsive motor and a light feel, the ’87 KTM 250 Motocross made an able flier. Photo Credit: Bob Carpenter

While the KTM’s power output was competitive, its clutch and transmission continued to be a major liability. Neither unit was liked by testers who complained of notchy engagement, false neutrals, and a total lack of feel. Under power, it was impossible to catch the next shift without backing off the throttle and feeding in some clutch. That clutch was slightly better for ’87, but the unit continued to offer a weird feel and long throw. In order to engage the clutch, it was necessary to pull the lever all the way into the bar, and it would not fully disengage until the lever was completely released. The engagement point was rather sudden and riders complained of a “hinged” feel that made it difficult to modulate. There was also a slight creep to the unit that only got worse as the plates heated up. Overall, these were the weak links in an otherwise competitive motor package.

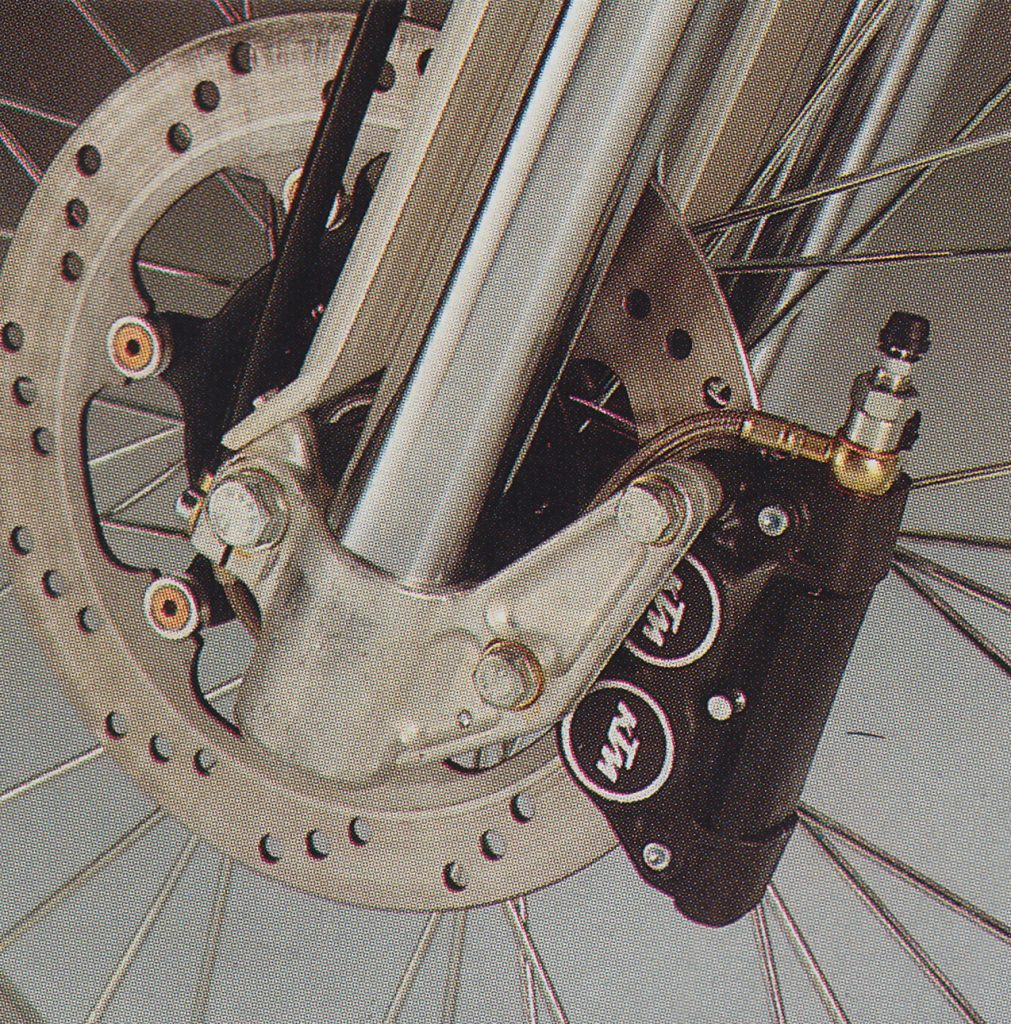

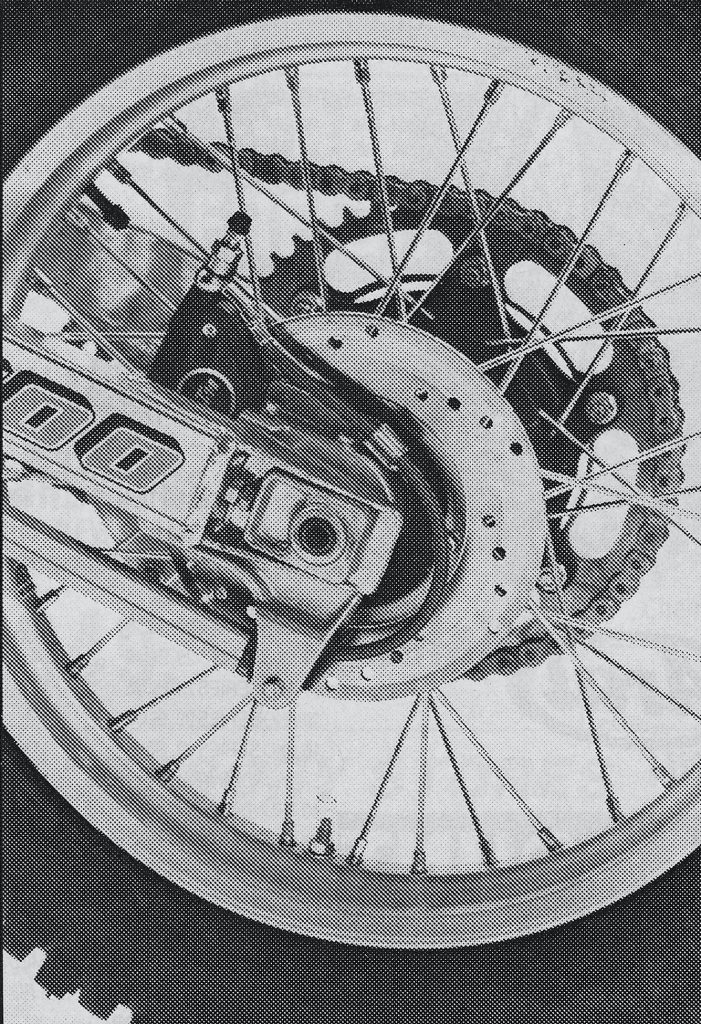

A new dual-piston front caliper for 1987 greatly improved the KTM’s previously mediocre braking performance. Photo Credit: KTM

On the suspension end of things, the KTMs premium components were let down by their poor settings. In spite of offering class-leading technology, the 250MX’s inverted 4054 forks delivered one of the worst rides in the class. The spring rates were absurdly soft for any serious motocross use and the damping was tuned more for woods work than blasting through whoop sections. They worked reasonably well on small chatter, but slammed to the stops on hard hits and hung down in the stroke perpetually. If you stiffened up the springs the droop went away, but then the light damping wanted to catapult you to the moon. Unfortunately, the only real solution was to find a shop familiar with the Dutch components and have them sort out the springs and damping. Considering how well these forks performed on other machines like ATK’s 560 super-thumper, the potential was certainly there, but it took a savvy tuner to properly extract it.

Always notorious for their absurdly hard seats, a new softer compound for ’87 pleased the backside of testers. Photo Credit: KTM

Out back, the picture was much better for KTM owners. The Dutch White Power Super Adjuster shock was well sprung and at least in the ballpark for most riders. It was plush on small hits, while still offering sufficient bottoming resistance for those Heinz Kinigadner types. Overall damping was well controlled, but some riders felt rebound was a bit quick in the rough. Compared to the competition, the KTM’s damper was rated below the ultra-plush RM and new bottom-link KX, but above the harsh YZ and utterly confused Honda.

In an interesting combination of old and new, all of the 1987 full-size KTMs all featured a torque arm on their rear disc brakes. This holdover from the days of drum brakes was designed to isolate the rear suspension from the forces of brake torque. Photo Credit: KTM

In the handling department, the new KTM proved a significant step forward over previous Austrian offerings. The new chassis turned far better than ’86, but still lacked the precision feel of the best Japanese handlers. With the stock springs in place, the lowrider front yielded an impressive willingness to change direction, but the resulting unbalanced chassis made the bike vague-feeling at speed. With stiffer springs, the high-speed handling improved greatly, but the bike never felt completely planted. For riders accustomed to European machines, it was a huge improvement, but for those groomed on the razor-sharp feel of a Honda, it was a bit disconcerting.

With 90% of its DNA shared between the Enduro and MX versions, the KTM was by far the most versatile machine in the 250 class. Minor mods were all that was needed to transition from track to trail on the Katoom. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Braking performance on the rear of the KTM was superior to the drum of the outdated Yamaha YZ250, but not up to stuff with the powerful units found on the KX and CR in 1987. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the details front the KTM was excellent for its time. The high-quality Italian plastic fit well, looked good and lasted long. Most riders praised the thin layout and comfortable ergonomics. The brakes, while not as strong as the Nissin units found on a CR or KX, were certainly competitive and a huge improvement over the lackluster ’86 versions. Aside from its left-hand kicker, the rest of the bike felt more-or-less like any machine from Japan. The new softer seat was a huge improvement and appreciated by everyone who had endured the bricks KTM had been pawning off as seats on their previous machines. The hand controls, bolt selection, and overall construction were still very European, but the bike no longer felt like it was built for a different sport. If you could ride a Kawasaki, then you hop on the KTM and feel at home within a few laps.

In 1987, KTM offered the most versatile and longest-lasting packages in the 250 class. With very few mods, it could be raced in the desert, in the woods, and on the track. For hard-core motocross, there were probably better choices available, but if you were looking for a do-it-all machine, it was hard to go wrong with the white and blue Katoom. Photo Credit: KTM

In 1987, KTM made a concerted effort to bring their 250-class entry into the motocross mainstream. A new snappy motor, slimmer ergonomics, and a sharper handling chassis all catered to a generation of American racers bred on the cut-and-thrust action of the 125 class. Well built, with premium, components throughout, the KTM 250 had a lot to offer in 1987. Its suspension needed to be sorted out, and its transmission was cranky, but once you warmed to its uniquely European charms you had a bike that was one of the most capable and versatile in the 250 class.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram – @TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com