For this first installment of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the machine that took Dave Strijbos to the 1986 World Motocross Championship, Cagiva’s 1986 WMX 125.

By: Tony Blazier

While not well known in the US, Cagiva was an international motocross power in the mid-eighties. In 1985 and 1986, the Italian brand captured back-to-back 125 World Motocross titles. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While not well known in the US, Cagiva was an international motocross power in the mid-eighties. In 1985 and 1986, the Italian brand captured back-to-back 125 World Motocross titles. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Today, the name Cagiva is probably best remembered in the motocross world for its purchase of the Husqvarna brand in the late eighties. Once the owners of Husqvarna, Ducati, and MV Agusta, Cagiva was a motorcycling powerhouse in the eighties and nineties. Founded by Giovanni Castiglioni in 1950, the Cagiva brand was originally a manufacturer of small metal components. The name “Cagiva” was derived from a combination of the founder’s name and the town in which it originated – Varese, Italy (CAstiglioni GIovanni and Varese). It was not until 1978 that Cagiva expanded into motorcycle production. At the time, American motorcycle manufacturer AMF-Harley Davidson had a substantial motorcycle production facility in Varese building small two-strokes for sale under the Harley banner. Seeing an opportunity to expand their business, Castiglioni’s two sons Claudio and Gianfranco decided to diversify the company’s offerings by acquiring the AMF-Harley-Davidson/Aermacchi factory and starting to build motorcycles. Initially, the new Cavigas were nothing more than re-badged AMF-Harleys, but eventually, the Italians began producing unique machines of their own.

Pekka Vehkonen’s 125 World Championship victory for Cagiva in 1985 was the first for a non-Japanese brand since the inception of the series in 1975. Photo Credit: Michel Moncler

Pekka Vehkonen’s 125 World Championship victory for Cagiva in 1985 was the first for a non-Japanese brand since the inception of the series in 1975. Photo Credit: Michel Moncler

While early Cagiva motocross machines were slightly odd in appearance, their motor performance was never in question. The Italians knew how to make horsepower and the machines were never lacking for forward thrust. In America, they remained little more than a curiosity, occasionally showing up in magazine tests and the odd USGP. At the time, most US riders had fallen out of love with the machines of Europe and in love with the machines of Japan. Cagivas may have been great, but few American riders had an opportunity to experience their uniquely Italian flair.

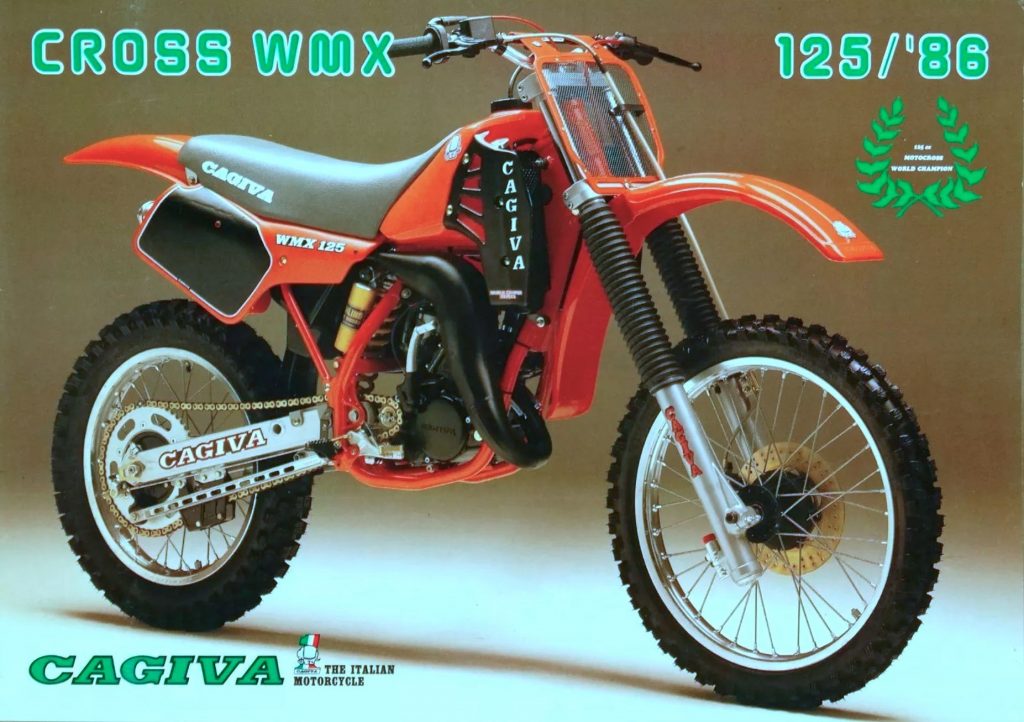

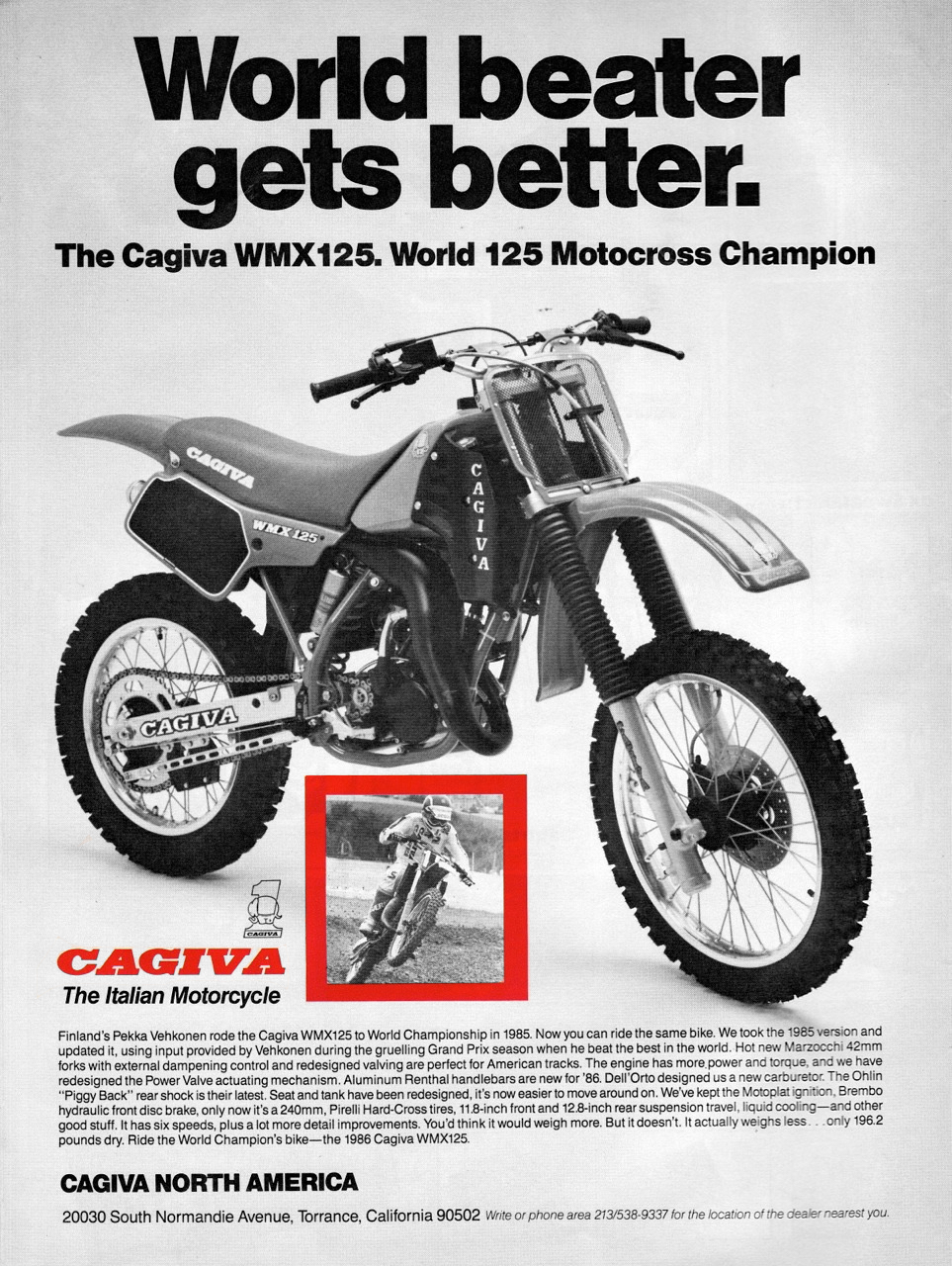

Cagiva’s 1986 WMX 125 was marketed as a replica of Pekka Vehkonen’s ’85 works bike. Photo Credit: Cagiva

Cagiva’s 1986 WMX 125 was marketed as a replica of Pekka Vehkonen’s ’85 works bike. Photo Credit: Cagiva

In 1985, Cagiva finally broke into the motocross mainstream by winning the 1985 125 World Motocross title with Finland’s Pekka Vehkonen at the controls. This was the first win of the 125 World Title by a non-Japanese brand since the series was started in 1975. In addition to Vehkonen’s victory, the brand scored a third overall in the championship standings with Italy’s Corrado Maddii rounding out the 1985 125 podium. In a mere seven years, Cagiva had gone from a producer of rehashed Harley street bikes to the winners of one of the most prestigious motocross series in the world.

In 1987, Cagiva purchased Husqvarna’s motorcycle operations and brought them under the Cagiva banner. Photo Credit: Cagiva

In 1987, Cagiva purchased Husqvarna’s motorcycle operations and brought them under the Cagiva banner. Photo Credit: Cagiva

For 1986, Cagiva looked to capitalize on this impressive victory by introducing a “World Championship Replica” version of the bike that took Vehkonen to the ’85 title. The new machine was based loosely off of the 1985 design but featured several changes aimed at improving its performance. Revisions to the frame, suspension, bodywork, and motor all looked to increase the appeal of the WMX to the American market and bring the Italian Stallion up to speed with its far-East rivals.

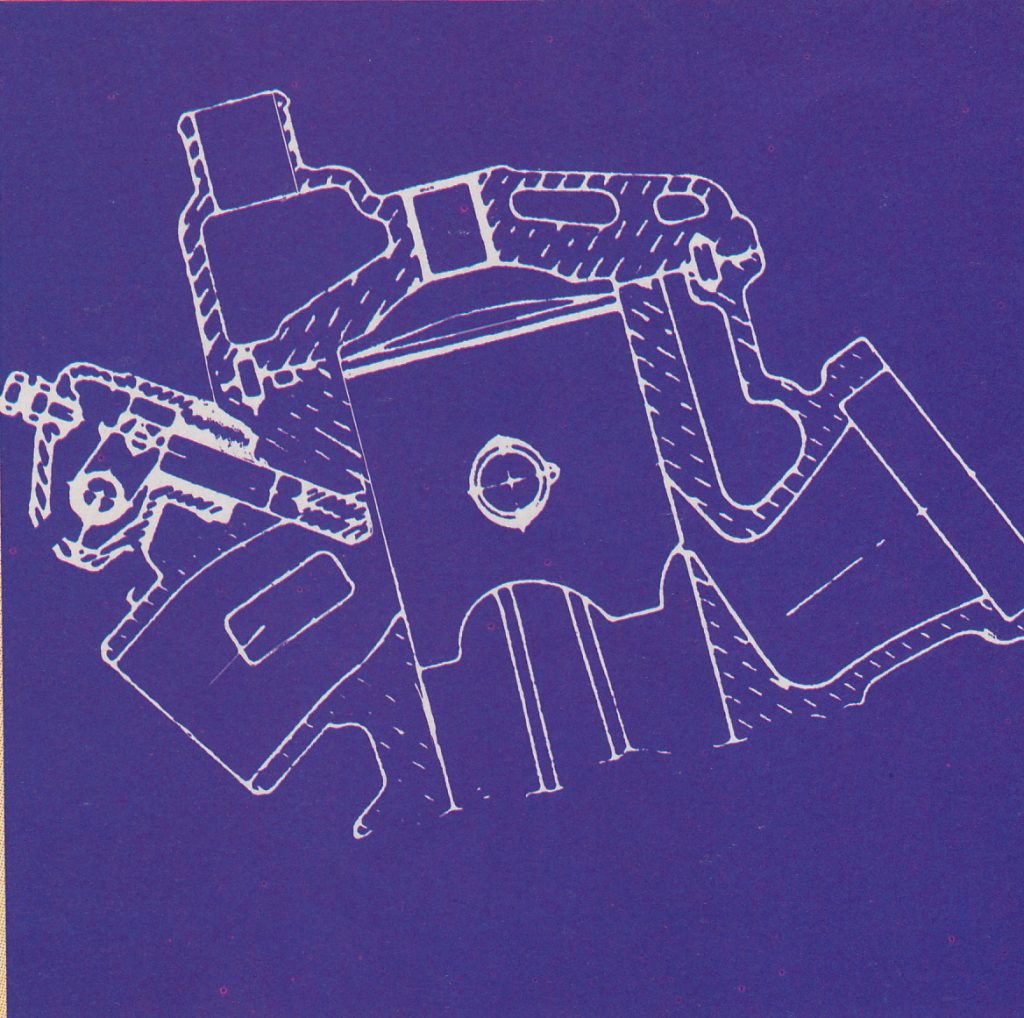

In 1986, the Cagiva’s motor was as advanced as anything in the class. It featured a Nikasil liner and a version of a variable exhaust port Cagiva called the “Cagiva Torque-increase System” (CTS). The CTS was similar in theory to Yamaha’s YPVS but the Italian machine used a sliding guillotine-valve to alter port timing instead of the Yamaha’s rotating drum. Photo Credit: Cagiva

In 1986, the Cagiva’s motor was as advanced as anything in the class. It featured a Nikasil liner and a version of a variable exhaust port Cagiva called the “Cagiva Torque-increase System” (CTS). The CTS was similar in theory to Yamaha’s YPVS but the Italian machine used a sliding guillotine-valve to alter port timing instead of the Yamaha’s rotating drum. Photo Credit: Cagiva

While the WMX 125 was certainly different than the Japanese machines in many ways, it was not behind them in terms of technology. The 124.6cc two-stroke motor was as up-to-date as anything in the class in 1986. The motor featured a 56mm x 50.6mm bore and stroke and 11.0:1 compression ratio from its single-ring piston. Internally, the ’86 cylinder featured all-new porting and the same high-tech Nikasil liner as the new Hondas. Like the Japanese 125s, the WMX featured a variable-exhaust valve designed to broaden power. This Italian version of a “power valve” was coined the “Cagiva Torque-increase System” (CTS) and featured a sliding guillotine-valve that varied the exhaust port timing based on engine rpm. For 1986, the CTS featured a redesigned mechanism for smoother engagement.

The 1986 crop of 125s was a very diverse field but none of them were up to toppling Honda’s omnipotent CR125R. Photo Credit: Cycle World

The 1986 crop of 125s was a very diverse field but none of them were up to toppling Honda’s omnipotent CR125R. Photo Credit: Cycle World

On the intake side, Cagiva kept things close to home by spec’ing an Italian-built 36mm Dell’Orto carburetor for the mixing duties. The intake remained a conventional cylinder-reed design but new reeds for ’86 promised quicker response. The ignition duties were handled by an electronic Motoplat unit that featured an automatic advance. Finishing off the motor changes for 1986 were a redesigned pipe and silencer that were tuned to work with the new motor’s porting profile.

The Cagiva’s 124.6cc mill offered a short but potent spread of power. There was not a lot of power at the extremes, but it was very strong through the middle. As long as you could keep it in its sweet spot it was more than competitive with its Japanese rivals. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The Cagiva’s 124.6cc mill offered a short but potent spread of power. There was not a lot of power at the extremes, but it was very strong through the middle. As long as you could keep it in its sweet spot it was more than competitive with its Japanese rivals. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In the chassis department, the new ’86 WMX featured an all-new 4130 chrome-moly single downtube frame. Unlike many Japanese bikes of its time, the Cagiva’s frame featured a fully removable subframe that made servicing easier. Complementing the new frame was redesigned bodywork that slimmed and flattened the pilot’s compartment. The new tank featured a lower center of gravity to aid handling and a lower profile on top to aid rider movement. A redesigned saddle carried much farther up the tank and featured a slightly softer (but still ridiculously hard) seat foam for improved rider comfort. Finishing off the rider compartment was a set of trick Renthal alloy bars (nearly twenty years before the Japanese machines would receive this feature) and European-spec Domino levers.

Every 1986 WMX 125 proudly proclaimed the WMX to be a “World Championship Replica.”

Every 1986 WMX 125 proudly proclaimed the WMX to be a “World Championship Replica.”

On the suspension end of the equation, the Cagiva featured high-end European components both front and rear. Up front, the WMX featured a very unique set of 42mm conventional Marzocchi forks that delivered 11.8-inches of overall travel. These forks allowed for both compression and rebound adjustability, a feature unseen on any of the Japanese machines in 1986. In a nod to the SFF forks that would come three decades later, the WMX’s forks featured a single spring on one side with compression damping being handled by one fork and rebound being handled by the other.

The ’86 WMX featured all-new ergonomics that seemed somewhat odd to many riders of the time. The new seat and tank gave the bike a very flat and slim rider’s compartment and the rock-hard seat foam prevented the “sit-in” feel riders of the time were accustomed to. Today, these “sit-on-top” ergonomics would be familiar to anyone who threw a leg over the WMX but in 1986 this was radically different from the norm. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The ’86 WMX featured all-new ergonomics that seemed somewhat odd to many riders of the time. The new seat and tank gave the bike a very flat and slim rider’s compartment and the rock-hard seat foam prevented the “sit-in” feel riders of the time were accustomed to. Today, these “sit-on-top” ergonomics would be familiar to anyone who threw a leg over the WMX but in 1986 this was radically different from the norm. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

By far the weakest link of the ’86 WMX’s performance package were its grim stock forks. These 42mm Marzocchi units were actually very advanced for the time, featuring an early version of Showa’s Separate Function Fork (SFF) design. In spite of its innovative construction and the most adjustability in the class they offered abysmal performance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

By far the weakest link of the ’86 WMX’s performance package were its grim stock forks. These 42mm Marzocchi units were actually very advanced for the time, featuring an early version of Showa’s Separate Function Fork (SFF) design. In spite of its innovative construction and the most adjustability in the class they offered abysmal performance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The ’86 WMX 125 featured Marzocchi’s new M-1 fork design which carried a separate valving circuit in each fork to handle compression and rebound. The right fork carried the single spring and the rebound circuit (that red knob that resembles Kawasaki’s triple-air fork was used to adjust the rebound damping) while the left fork handled all the rebound control. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The ’86 WMX 125 featured Marzocchi’s new M-1 fork design which carried a separate valving circuit in each fork to handle compression and rebound. The right fork carried the single spring and the rebound circuit (that red knob that resembles Kawasaki’s triple-air fork was used to adjust the rebound damping) while the left fork handled all the rebound control. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

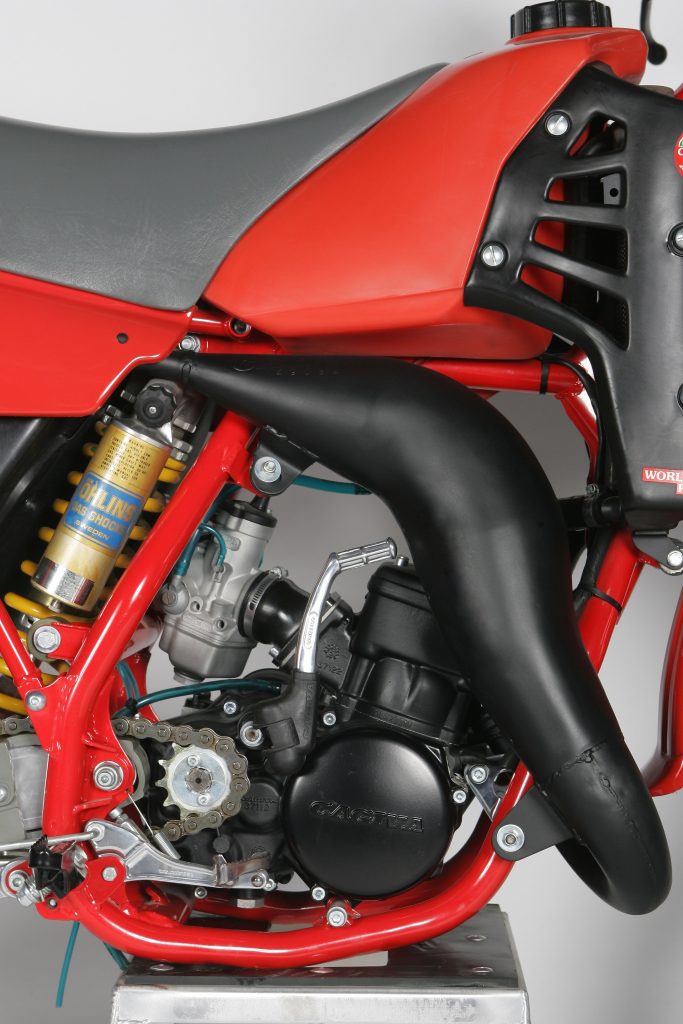

Out back, the WMX featured a version of a rising-rate single-shock suspension system Cagiva called “Soft Damp.” This bottom-link design was similar to what was found on bikes like Honda’s CR125R and featured a premium Swedish Öhlins damper. The shock offered 12.2 inches of travel with adjustments for compression and rebound damping. For 1986, new valving was spec’d to improve performance.

While the motor’s strong burst was praised by many, no one loved the WMX’s finicky stock Dell’Orto carburetor. Once properly jetted it worked well enough, but the mixer was hyper-sensitive to changes in temperature, elevation, and humidity. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While the motor’s strong burst was praised by many, no one loved the WMX’s finicky stock Dell’Orto carburetor. Once properly jetted it worked well enough, but the mixer was hyper-sensitive to changes in temperature, elevation, and humidity. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the track, the ’86 WMX 125 proved a potent competitor to its Japanese rivals. By far its best trait was its powerful motor that delivered a very strong midrange blast. There was not a lot of thrust above or below this surge, however, so care had to be taken to keep it in this sweet spot. This was similar to the new ’86 YZ125 which offered a strong midrange but relatively short pull. When it was on the pipe it was as fast as anything available in 1986, but it took a talented rider to make the most of its punchy power profile. The power spread was slightly broader than the pipey ’85 WMX but it remained a demanding engine to use effectively. Both the transmission and clutch were good though and that helped when it came time to snatch that next gear. Honestly, in 1986, all of the 125s other than the CR125R had powerband issues that made them a challenge to ride fast. Only the Honda covered all the bases and that is one of the main reasons it dominated the standings. In the right hands, the Cagiva’s power plant was certainly competitive with its Japanese rivals and that was no small feat for a European 125 of the time.

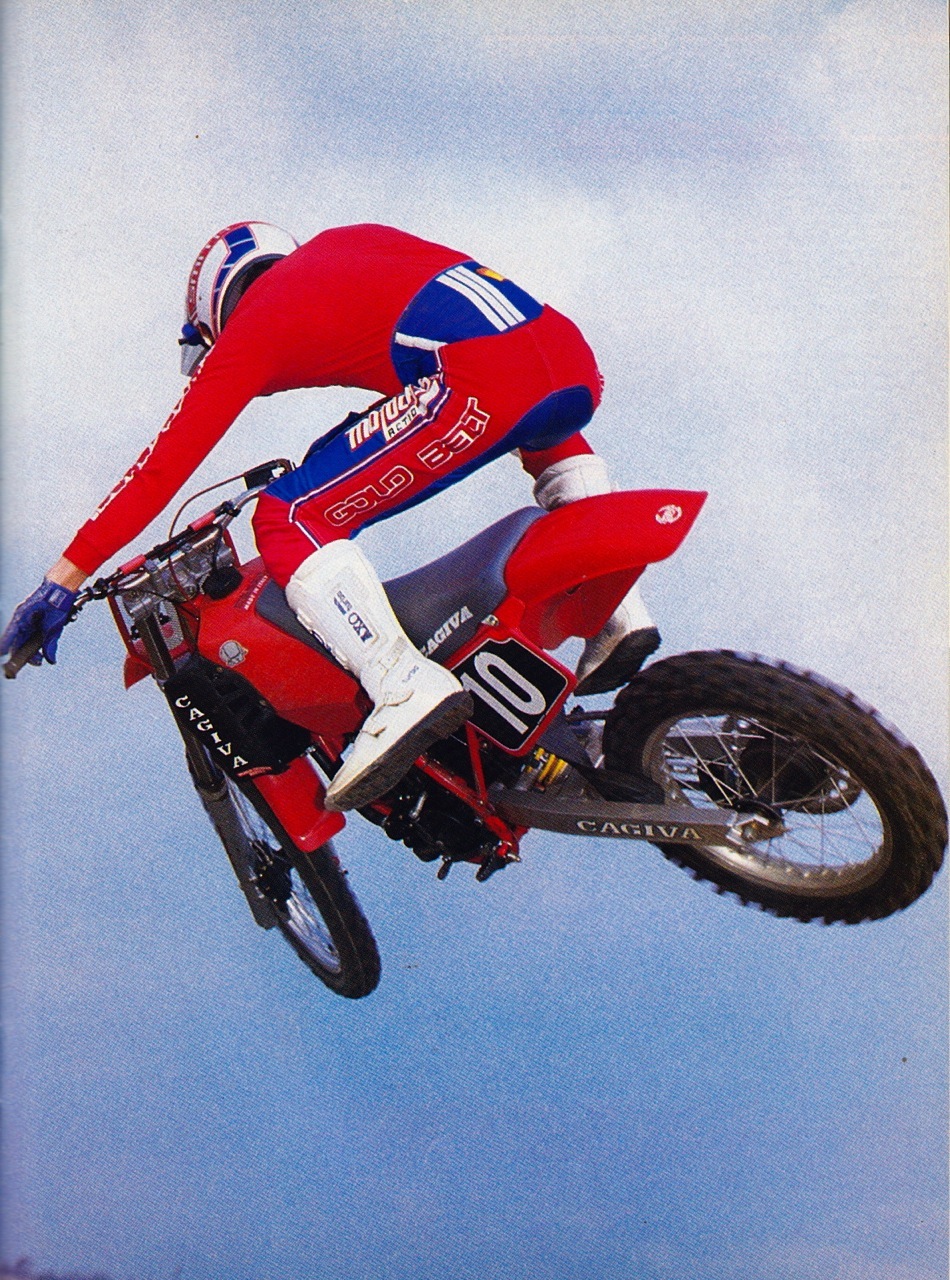

With slim ergonomics, a light feel, and a strong midrange, going big on the ’86 WMX was a piece of cake. Landing, well that was a different matter… Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With slim ergonomics, a light feel, and a strong midrange, going big on the ’86 WMX was a piece of cake. Landing, well that was a different matter… Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the Cagiva’s motor was a contender, the same could not be said of its stock suspension package. On paper, the WMX offered the most sophisticated suspension components in the class, but that did not translate to winning performance on the track. Its Marzocchi M-1 forks and Öhlins shock were some of the most advanced units available, but their setup from the factory was completely at odds with what most American riders had come to expect from their Japanese machines. Of course, much of this was probably due to the extreme differences found at the time between the tracks in Italy and SoCal. If the Italians would have had the infrastructure to properly test and set up their machines just for the American market they may have fared better, but as it was, the WMX’s setup pleased no one on this side of the pond.

This WMX once owned by Greg Primm has a steel bar installed but the stock WMX actually came standard with Renthal alloy bars in 1986. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

This WMX once owned by Greg Primm has a steel bar installed but the stock WMX actually came standard with Renthal alloy bars in 1986. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In stock condition, the forks were softly sprung and very heavily damped. This was a problem Honda would face a few years later with their switch to inverted forks. In both cases, riders were not impressed with the performance this setup provided. The fork’s action was incredibly harsh and unforgiving on the small chop and equally wrist-abusing on hard hits. They hung down in the stoke and hit a valving wall when encountering the sharp type of hits common to a motocross track. Several testers tried experimenting with Marzocchi’s many adjustments but none of them found an acceptable setting. With stiffer springs installed and a proper re-valve (by a tuner familiar with the unique Italian forks), there was a lot of potential available, but in stock condition, they were the worst forks in a very mediocre ’86 field.

Another area of concern on the stock WMX was its brakes. The front disc/rear drum combo was weak, numb, and prone to glazing over the stock pads and shoes.

Another area of concern on the stock WMX was its brakes. The front disc/rear drum combo was weak, numb, and prone to glazing over the stock pads and shoes.

One nice thing about buying a Cagiva was the quality of the stock components. Items like this high-dollar Öhlins shock would have set you back the quarter of the cost of a new CR125R in 1986. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

One nice thing about buying a Cagiva was the quality of the stock components. Items like this high-dollar Öhlins shock would have set you back the quarter of the cost of a new CR125R in 1986. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In the rear, the situation was not quite as dire. Once again, the spring rate was too light for most tester’s tastes, but the shock’s action was not as grim as the forks. In stock condition, it tended to kick on stutter bumps and was generally busy in action but with careful setup and a spring swap, it performed well enough to at least be raceable. No one really loved the shock, but at least it was useable and offered a great deal of potential if properly sorted out.

The Soft Damp rear suspension on the ’86 WMX was a better performer than the woeful Marzocchi forks. The valving and spring rates were out of step with the typical American tastes of the time, but it could be made to work acceptably with some careful setup. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The Soft Damp rear suspension on the ’86 WMX was a better performer than the woeful Marzocchi forks. The valving and spring rates were out of step with the typical American tastes of the time, but it could be made to work acceptably with some careful setup. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the handing front, the WMX was a very middle-of-the-road contender. Turning was about on par with the YZ and better than the KX, but not nearly as precise as the CR. On fast straights, it resisted the urge to shake its head like the Honda but was not quite as planted as the Yamaha. Here, the poor suspension did not work in the Cagiva’s favor. In the air, the WMX was a neutral flier, but most riders found its “sit on” layout and rock-hard seat slightly off-putting. Today, both of these features would be par-for-the-course, but in 1986, most bikes had “sit-in” ergonomics and marshmallow seats. One area where the WMX was lacking compared to its rivals was in the braking department. The front single-piston Brembo brake was underpowered and wooden in feel and the rear drum was only barely adequate to stop the Cagiva’s modest 196 pounds.

The stock silencer on the WMX was a decent performer when fresh but the mounting was fragile and the packing tended to blow out quickly. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The stock silencer on the WMX was a decent performer when fresh but the mounting was fragile and the packing tended to blow out quickly. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the detailing front, the Cagiva was very well-appointed for the time. The Renthal bars, Domino controls, and high-end suspension hardware were all premium-quality items that would have cost extra to add to any of the Japanese machines. The seat foam, while hard as concrete, was at least long-lasting. The bike even came with a full set of spares including alternate gearing, several O-rings, and gaskets.

In 1986, Cagiva was the fifth-largest seller of motocross bikes in the world. Rare in the US, their unique Italian flair was mostly lost on Americans, but they offered a lot of potential to those willing to embrace their peccadillos and polish their rough edges. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1986, Cagiva was the fifth-largest seller of motocross bikes in the world. Rare in the US, their unique Italian flair was mostly lost on Americans, but they offered a lot of potential to those willing to embrace their peccadillos and polish their rough edges. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In the end, the 1986 Cagiva WMX 125 proved that Europe could indeed compete with the Japanese in the 125 class. The World Championship replica offered a strong motor, solid-handling chassis, and top-quality components. If only it had offered a small amount of suspension finesse it might have given its Nipponese competitors a run for their money, but as it stood, it was a fork and shock away from running at the front.