For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s all-new CR125R for 1984.

In ’84, Honda was far from the juggernaut they would become later in the decade. The performance of the red machines had been very uneven through the late seventies and early eighties. One year they would produce a winner, only to follow it up with an underperforming mess the next year. After the excellent bikes they had turned out in ’83, the lackluster ‘84s were a major disappointment to the Honda faithful. Photo Credit: Honda

The early eighties were a strange time for Honda. At that point, they had not yet earned the incredible reputation for outstanding quality and performance that they enjoy today. After single-handedly legitimizing the 125 class with their first CR125M, they proceeded to squander that lead with a lackluster run of follow-ups in the late seventies. While Honda stumbled, Suzuki surged ahead with innovative and excellent performing 125s. In 1980, Honda scored a bit of a coup by hiring five-time World Motocross Champion Roger DeCoster away from longtime rival Suzuki. DeCoster’s arrival turned out to be a huge win for Honda. His many years of motocross expertise proved instrumental in turning around Honda’s troubled motocross program. Within three years, Honda would go from producing some of the worst machines in motocross in ’81, to some of the best by 1983.

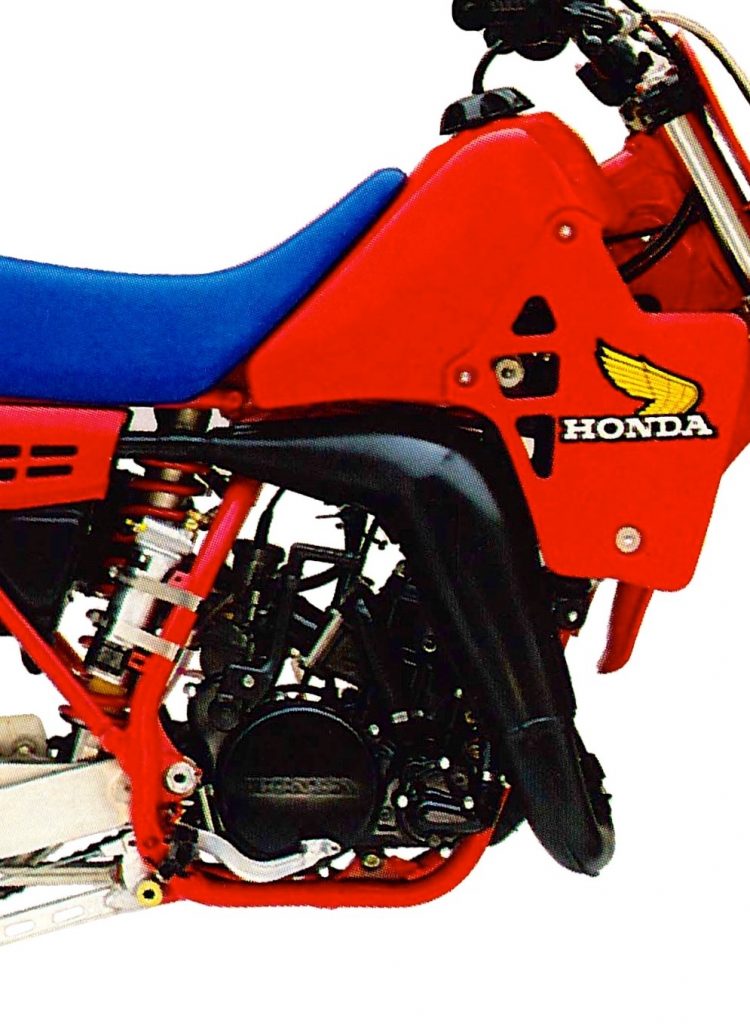

The new ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) equipped CR motor was actually a step back from the non-power-valve ’83 power plant. It produced all of its power in the lower RPM range and felt choked off on the top end. Compared to the class-leading KX125 mill the CR was down on power everywhere. Photo Credit: Honda

After the incredible success of the ’83 CRs, Honda had a lot to live up to in 1984. The CR125R had not been the outright fastest 125 in ’83, (that honor fell to the KX125) but its blend of usable power, excellent handling, and workable suspension had taken home the crown of best overall 125 in the land. For ’84, Honda made the bold move of totally redesigning their shootout-winning tiddler. The new CR125R featured an all-new motor, new bodywork, reworked suspension, and an all-new chassis. The question would be, would all these changes result in another win for Honda, or would Big Red go from champ to chump in ‘84?

| The ATAC system consisted of a small chamber bolted to the bottom of the exhaust manifold and a small butterfly valve used to control exhaust flow. A centrifugally activated ball governor was employed to open and close the valve based on engine RPM. The theory behind it was to simulate two different expansion chamber profiles with one pipe. At low RPM, the ATAC valve would be opened to allow exhaust to pass through the chamber, and in effect, simulate having a larger head pipe. At higher RPM, the valve closed to allow unrestricted flow and better top-end power. Unlike the Yamaha YPVS, Kawasaki KIPS and Honda’s own HPP system, the ATAC afforded no means of altering port timing to further tune performance. Photo Credit: Honda |

For ’84, Honda did away completely with the ’83 125 motor and introduced an all-new power plant on the little CR. The new mill featured Honda’s first production application of a “power valve” to enhance the small mill’s narrow power delivery. The new ATAC system (short for Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) featured a small chamber mounted to the exhaust manifold that could be closed off by a butterfly valve at its opening. At low RPM the valve would be open, effectively increasing head pipe volume, and in theory, low-end torque. As RPM rose, the valve would shut, closing off the chamber and allowing unrestricted flow. Unlike the Yamaha Power Valve System (YPVS), the ATAC had no mechanism to alter exhaust port timing. Other than the addition of the ATAC, the ’84 CR’s motor was a straight forward two-stroke power plant. It used liquid-cooling, a reed-valve, and a cylinder-fed intake. Carburation duties were handled by a 34mm round-slide Keihin mixer.

|

| The original ATAC’s effectiveness was so dubious that many people either blocked it off or disconnected it completely. There was actually enough demand that companies like DG made special pipes and manifolds that eliminated the ATAC entirely. Honda would eventually sort out the new technology, and by ’86 the CR would be the new top dog in the 125 class. With some refinements, the ATAC system would be used on CR125R up until 1990, when Honda would replace it with their superior Honda Power Port (HPP) system. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

For all the work Honda put into the new ATAC motor, the results were less than awe-inspiring. The redesigned motor was strictly a low-to-mid range power plant. It came on with a strong (for a 125) low-end surge and pulled well into the midrange, but ran out of gas when revved out. Upshifting just before this midrange peak was the best way to make time on the red tiddler. If you tried to scream the motor, it only went slower.

On top of the lackluster power spread, Honda had some serious problems with quality control in ’84. Some CR125R’s ran decently, while others had no power whatsoever. There were issues with the ATAC systems not being timed correctly and many others had problems with improperly ported cylinders. Even if you were lucky enough to buy a “good” one, the CR was no match for the powerhouse that Kawasaki produced in 1984. The little KX had the motor of doom in ’84. It pulled cleanly down low like the CR, before blowing its doors off with meaty mid-range hit and shrieking top end. In 1984, only the anemic YZ125 ranked below the CR in the final standings.

|

| The best thing about the front of the CR125R was the new disc brake. Compared to the mediocre drums on most of the competition, it was a huge advantage. The front KYB forks were decent performers overall, with good spring rates and slightly harsh action. They were not as good as the class-leading RM forks, but better overall than the confused KX and YZ front ends. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

In the suspension wars, the ’84 CR125R was a bit of a mixed bag. Unlike the 250 and 500 that year that used Showa components, the 125 featured KYB suspension front and rear. The KYB forks were decent performers, with good spring rates and slightly harsh damping. They were not as smooth in action as the class-leading RM’s forks but they were at least usable in stock trim. The KYB shock, on the other hand, was terrible. It delivered a harsh, jarring ride on any surface and defied fixing in spite of its multiple adjustments.

|

| The KYB rear shock on the CR tied with the pathetic YZ for last in the field in ’84. It was harsh over any bump big or small. It did afford the rider a great deal of tunability, with both compression and rebound damping adjustments. Unfortunately, no amount of tinkering could improve its sub-par performance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

Prospects were better for the CR in the handling department. In ’84, it was by far the best turning bike on the track. Nothing could turn under the Honda in a tight corner. The flip side, however, was the worst headshake of any of the 125s. The little CR could shake its head bad enough to rip your hands off the bars at speed. It was a definite trade-off, but most 125 riders were willing to live with the schizophrenic handling at speed in return for the razor-sharp turning. Aiding the handling was the sleek new bodywork and excellent ergonomics, that made the bike easy to move around on and comfortable to ride.

|

| With a light feel and excellent ergonomics, the CR125 was one of the most comfortable bikes in the class in 1984. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

Braking on the new CR125R was also a bright spot. The ’84 model CR’s were the first to feature a front disc brake and it was a huge upgrade from the previous year’s front drum arrangement. In the rear, the CR still used a drum, but it worked excellently at slowing down the lightweight 125. It’s only real competition in stopping was the Kawasaki. It also featured a front disc, but Honda’s front binder was less grabby and easier to modulate than the green machines.

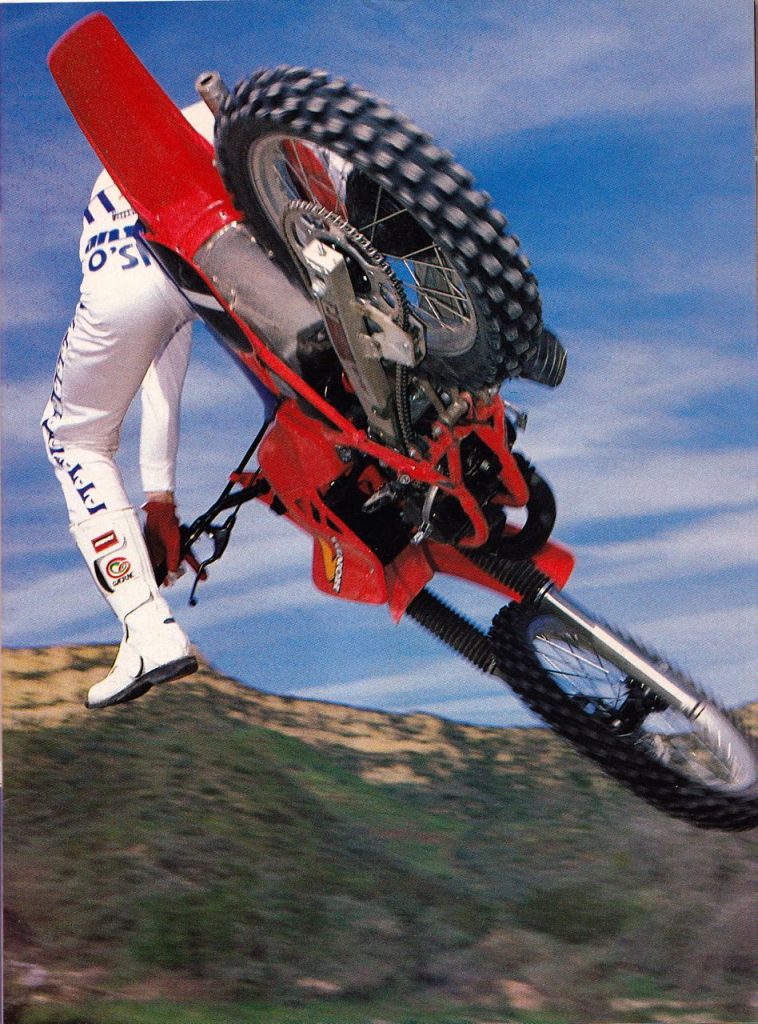

The CR125R was an excellent flyer in 1984. 125 National champion Johnny O’Mara demonstrates. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Living with the little CR was a pleasurable experience for the most part. The new plastic looked great, fit perfectly and wore extremely well. The seat was well shaped, with comfy foam that seemed to last much longer than the competition. The trick, fully removable subframe made shock servicing a piece of cake. Overall, build quality was excellent for the time, with quality fasteners and a well thought out design. Aside from the mysterious missing power on some models, the only real issue with the motor was maintenance on the ATAC. The ATAC tended to collect sticky, slimy exhaust goo at an alarming rate and if left unchecked, would clog up the mechanism. If you went too long between services, it was virtually impossible to get all the baked-on crud out of the system. Considering the ATAC did virtually nothing for the power anyway, it was no major loss.

|

| Honda took a bit of a gamble in ’84, redesigning the machines that had dominated the competition the year before. Unfortunately the gamble did not pay off and as a result CR owner got left in the dust. The lessons learned would be put to good use, however. After the disappointment of ’84, Honda would go on quite a run, dominating the 125 class for more than a decade. Photo Credit: Stephane LeGrand |

Overall, the entire CR line in ’84 was a major disappointment for Honda. After capturing shootout victories in all three classes in ’83, the redesigned ’84s were far less successful. Both the CR500R and CR250R turned out to be brutally fast, but unreliable time bombs (MXA recommended buying CR250R pistons in six packs that year). The CR125R, on the other hand, was reliable, but underpowered. With Kawasaki producing an absolute rocket of a 125, it was difficult for the mellow CR to even compete. In a class where horsepower is everything, the CR125R brought a knife to a gunfight in 1984.